Dear Editor:

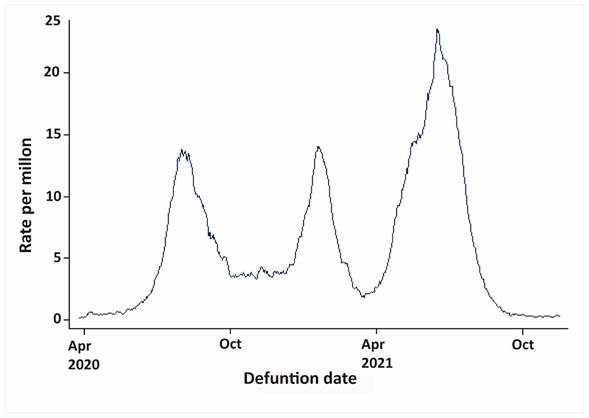

The behavior of the COVID-19 pandemic during the three peaks registered in Cali has been heterogeneous, and the severity of infections and deaths has varied over time (Figure 1). Cali, with 2.2 million inhabitants, is the third most populated city in Colombia 1; as of November 21, 2021, it has recorded 285 thousand confirmed cases and 7,474 deaths due to the infection 2. The vaccination plan against SARS-CoV-2, which was started in February, has immunized 1.54 million people in Cali 3.

Figure 1 Cali, Colombia. Mortality due to COVID-19 during the development of the national vaccination plan between April 2020 and November 2021. Monthly moving average. The first peak began on June 7 and ended on August 13, 2020. The second peak began on December 13, 2020; and ended on February 3, 2021. The third peak began on March 25 and ended on August 8, 2021; it was the deadliest and caused half of the deaths of the entire pandemic in Cali.

As in the rest of the country, the development of the vaccination plan in Cali coincided with the third peak of the pandemic, the most lethal and prolonged; as well as with multiple social mobilizations of hundreds of protesters who crowded the streets, between May and June 2021, protesting against an unpopular tax reform enacted by the national government. In Cali, the vaccination plan was also affected by lack of access to health services and vaccination points due to blockages registered in different zones of the city. At the end of the third peak, the country faced difficulties in continuing with the vaccination plan due to barriers to accessing vaccines in the international market.

In accordance with the national mandate, all SARS-CoV-2 virus infections diagnosed in the country's private and state laboratories must be notified to the Public Health Secretaries. In case of doubt, the territorial entity, the municipality of Cali in our case, analyzed each of the deaths and determined which ones were caused by COVID-19. From February to November 2021, city laboratories reported 139,972 SARS-CoV-2 infections and 3,312 deaths for COVID-19. This figure corresponds to 64% of the deaths that occurred in Cali during the pandemic. 82.5% of infections and 89.1% of deaths occurred in persons with incomplete vaccination schemes or unvaccinated people.

As it has been reported in other countries, the effectiveness of vaccines to prevent deaths from COVID-19 is variable and lower than that observed in clinical trials 4. The effectiveness of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 was estimated with the hazard ratio (HR) using a Cox proportional hazards model considering as a predictor covariate the vaccination status of each individual in different times. Changes in HR associated with partial immunization (≥14 days after receiving the first dose and before receiving the second dose) and complete immunization (≥14 days after receiving the second dose), further adjusting for age, sex, presence of comorbidities and vaccination week.

Mortality from COVID-19 in the city of Cali changed / dropped from a daily average of 15 deaths in November 2020 to 3 in November 2021. The risk of dying was higher in the unvaccinated, in men compared with women (HR: 1.96, CI 95%: 1.83-2.10), and in people with comorbidities (HR: 2.74, 95% CI: 2.55-2.94). An 8% increase for each year of age was evident. Of special interest was to observe variations according to the type of vaccine Table 1.

Table 1 Cali, Colombia. Effectiveness of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2

| Variable | HR | CI (95%) | Effectiveness % | CI (95%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine | Not vaccined | 1 | |||

| AstraZeneca | 0.40 | 0.30-0.53 | 59.7 | 48.3-71.1 | |

| Coronavac | 0.38 | 0.29-0.49 | 62.4 | 52.6-72.3 | |

| Jannsen | 0.11 | 0.05-0.25 | 89.1 | 80.2-98.0 | |

| Moderna | 0.02 | 0.01-0.09 | 97.8 | 94.8-100.8 | |

| Pfizer | 0.26 | 0.19-0.35 | 74.4 | 66.3-82.6 | |

| Vaccination status | Not vaccined | 1 | |||

| Complete immunization | 0.12 | 0.07-0.20 | |||

| Vaccination week | Weeks since the beginning of the plan | 0.99 | 0.98-0.99 | ||

| Sex | Female | 1 | |||

| Male | 1.96 | 1.83-2.10 | |||

| Age | Years | 1.08 | 1.07-1.08 | ||

| Comorbidity | Absent | 1 | |||

| Present | 2.74 | 2.55-2.94 | |||

Adjusting for vaccination status, age, sex, presence of comorbidities and vaccination week. CI: confidence interval.

Effectiveness of each vaccine (EV)= 1-HR, where HR is the exponential of the coefficient associated with the vaccine in the previously adjusted model. The confidence intervals of EV were estimated using the delta method 5.

Although vaccines against the SARS-CoV-2 virus showed 100% efficacy to prevent death, and 85-90% for severe disease in clinical trials 6, the effectiveness reported in the real world has been lower 7. Table 1 shows that in Cali, the effectiveness to prevent death from COVID-19 was lower than that reported in clinical trials; in addition, it showed variations according to the type of vaccine that was administered: 60% for AstraZeneca, 62% for CoronaVac, 89% for Janssen, 98% for Moderna, and 74% for Pfizer. Part of this variability may be due to the availability of vaccines and failures in compliance with the established times to adequately complete the vaccination schedule, as well as the capacities to develop the vaccination plan.

The conditions described in Cali and Colombia during the third peak could have favored the appearance of more contagious variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, but which could be controlled by current vaccines, probably because they evolved in an unvaccinated population 8. The a priori reasoning is that those who have been vaccinated and/or have recovered favor the appearance of collective herd immunity. The ones who die increase the percentage of vaccinated people, by reducing the unvaccinated population. However, the equation is more complex because unvaccinated groups can be reservoirs for the appearance of new variants that have evolved in the vaccinated population, and that be resistant to current vaccines, making those already vaccinated susceptible again.

In this globalized and interconnected world, herd immunity cannot be considered for isolated populations. There are differences in the variants between countries. While in Colombia, as of November 2021, the DELTA variant was the dominant one 9; in South Africa, a country with low vaccination coverage, it has emerged the OMICRON variant with 26 new mutations 10. It is urgent to accelerate the rate of vaccination to stop the chain of transmission and reduce the probability of the appearance of new variants. Further studies are required to determine in other regions the effectiveness of the various vaccines used in Colombia, considering the level of adherence and access to them.

text in

text in