" Hope is not the same thing as optimism. It is not the conviction that something will turn out well but the certainty that something makes sense, regardless of how it turns out ". Václav Havel

Talking about good death is a significant commitment. From clinical practice, it is possible to have a distant view, highly focused on the biological domains of the process, but unquestionably the most accurate and complete vision is the one that unites the biological component with the human component; that is, as part of a process that will also be part of my existence.

Whenever we reflect on our death or that of a loved one, our innate desire emerges for this moment to be free of unnecessary suffering, recognizing this as a fundamental right for any human being. Moreover, this right will always be governed by the dignity of the human being; dignity is the basic framework that supports this desire.

We live in a society that, in most scenarios, does not want to talk about death; even just naming it is prohibitive or " bad luck". Unfortunately, the clinical scenario has not been immune to this taboo., We were rarely told about dying or death during our training in the health school. Its process, or what it means, much less about how to accompany the process of dying or its importance, since death in the academy was almost always synonymous with therapeutic failure.

During these years of accompanying so many people in this process, I consider that this vision of death is simplistic and far from what it means. Accompanying the dying process is an art; doing it with the correct tools is a privilege. The possibility of accompanying such a sacred and transcendental moment of a person and their family is an experience that allows you to grow and transform both as a clinician and as a human being.

The End-of-Life Care Committee of the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies (IOM) 1 defines good death as ”" one free from avoidable suffering for patients and their families, by their wishes; and reasonably consistent with clinical, cultural, and ethical standards”. Recognizing the importance of having tools to accompany the dying process is an act of responsibility and respect in the face of the person's suffering in one of their most vulnerable moments. I found these tools in palliative care from the multidimensional vision that this approach offers to medicine.

Palliative Care is a philosophy of care, which includes a form of clinical care that for centuries had diluted with the development of hospitals and health technology. Being able to see the disease process of a person and their family from a broader perspective, understanding the impact on all dimensions of the person who suffers, and providing tools or strengthening resources from the genuine desire to alleviate their suffering is, in my experience, the most humane way of accompanying that to which we have turned our gaze to the attention centered on the person.

This is how palliative care has a place in all those situations that generate suffering related to health, recognizing the importance of the patient, family, or caregivers in the center of care; and assessing in an interdisciplinary way under the premise of total pain, to improve quality of life of people 2. In this way, the scope of palliative care is recognized as a tool to accompany multiple non-oncological medical conditions, complementing its primary specialty medical activity. Around 1% of the population suffers from one or several advanced chronic diseases, and over 60% present conditions such as frailty, dementia, multimorbidity, or geriatric syndromes 3,4.

It has been shown in the literature that the early integration of palliative care programs in chronic degenerative or progressive diseases 5 has an impact on the quality of life since it achieves: identification and relief of physical symptoms that impact the quality of life (e.g., pain, dyspnea or nausea), control of emotional symptoms, strengthening of acceptance, and adaptation to the diagnosis of a high-impact disease.In addition, it is possible to address topics such as the wishes and preferences of patients; for example, being able to sign, in advance, documents that express their will, as well as the participation of patients and their families in clinical decision-making.

Believing that the conditions for a good death can only be found in the last days is denying that the process of dying has everything to do with life itself; that is, with the biography, worldview, values, preferences, family or social context, and networks support; as well as with elements related to clinical care: the quality of the information that the treating team has been provided, the understanding of the vital prognosis, the quality of the interdisciplinary follow-up, and the expectations regarding the treatments.

Based on this reflection, we must assess the importance of assertive communication in the doctor-patient relationship, not only to inform the patient about the severity or prognosis within the framework of a high-impact medical condition or any chronic disease that we know will have a progressive evolution and possibly disabling; we must also learn to inquire into the 'patients' values and preferences; what is important to them. The impact that this disease may have on their roles, as well as on their families' dynamics, how much information they want to receive, and from whom they want to receive it. All these elements must be present within our consultation to carry out an element vital for conscious and consensual clinical care: Shared Care Planning6.

Shared Care Planning is defined as: "The process guarantees respect for people's autonomy, through which the entire community, family, and healthcare team that cares for them can learn about preferences and values. In this way, it will be possible to guarantee that the wishes will be attended to in the best conditions, in one of the most important moments of life, as it is the end-of-life process"

This process is validated under the ethical principles of autonomy, access to the truth, the right to be informed, and the concept of medical futility. Physicians and other professionals must respond to patients' need to be an active part of the decision-making process giving the value that it deserves to the moment when patients clearly and formally express these wishes and preferences 7. For different reasons, patients actively express these needs and must be listened to, welcomed, and attended. To be able to face these conversations, health professionals are required to be prepared, that is, to have managed issues such as their process of coping with death, their planning, and their desires and preferences.

In addition, health professionals are required to be prepared in order to be able to face these conversations. This implies that they have managed their issues, such as coping with their desires and preferences regarding death.

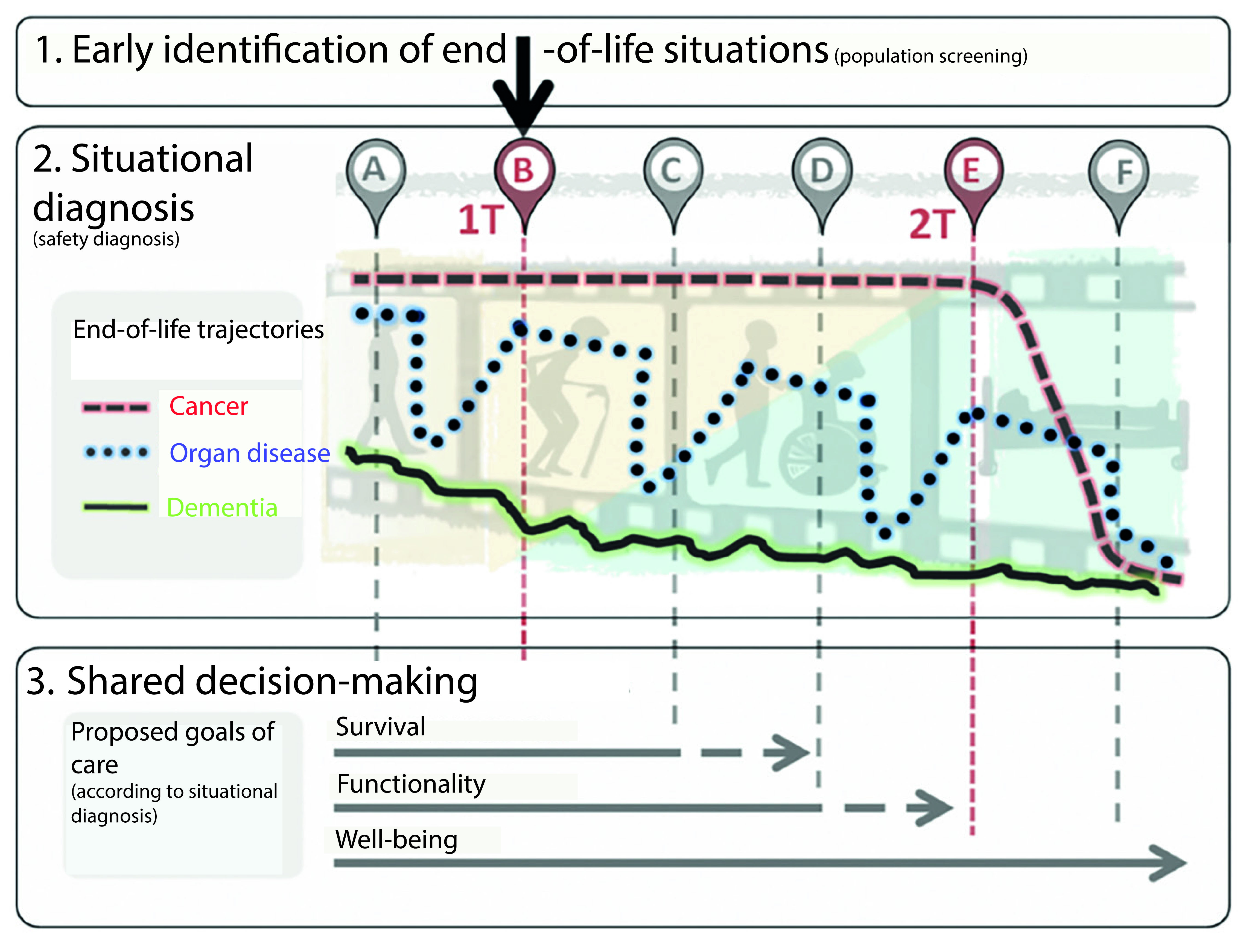

When we unite elements such as the patient's desires and preferences, values and vital history, knowledge of the trajectories of the disease, identification of transition stages of the disease (Figure 1); the social context, and the accompaniment of family/caregivers, clinical decisions are made centered on the person, which translate into timely and proportionate treatments, with the establishment of therapeutic ceilings; as well as clear clinical objectives that allow living a safe, conscious and compassionate disease process; reducing phenomena such as therapeutic obstinacy or medical futility.

Figure 1 Framework for early identification, situational diagnosis, and shared decision-making at the end of life. Taken from Amblàs 8. With permission from the publisher of the book.

After putting in perspective the necessary tools to define how the last days of life will be decided, I reflect on the current definitions of the concept of the "right to die with dignity," a term with which I disagree because '''dignity' does not belong to death, but to the person. Dignity is an inalienable quality of being, which no medical condition can take away.

Thus, the correct term for me is the right to have a good death. Unfortunately, in many respects, it has been created in recent years the false message that the only way to carry out the process of a good death is through euthanasia processes, which is an erroneous vision, taking into account all that this process implies, as I have already mentioned it. I believe that as a society from all spheres: politics, the media, and academia, among others, we must defend the right to Palliative Care with the same vehemence with which we defend access to the so-called "right to die with dignity", taking into account that universal access to palliative care allows people to benefit from these multidisciplinary tools that accompany and alleviate suffering at different stages of a disease.

The choices of how the actions will be carried out in the last days always align with my values and worldview. In the exercise of my autonomy, I can decide together with my health team to what extent I consider interventions to be carried out; where I want this process to take place; and something relevant, who will be the person who can make decisions for me, if I lose my decision-making ability. So, in advance, the documents that express my will become a way to clarify what I want for my last days; they are not the exclusive property of those who agree with the basic procedures 9. The possibility of signing, in advance, a will document under Colombian legal premises is the result of a reflective exercise of my own, with my loved ones, and with the health team, where I can capture everything that I want for myself, in full use of my faculties. That is to say, it may consider which interventions to be performed or which not to, as well as if my wish is to die at home or in an institution; or if I want to be given alternatives such as palliative sedation in case of refractory symptoms or suffering in the final process; and even how I wish my funeral rites to be performed.

A final reflection is that by being clear about the great dimension of the dying process, health professionals face a series of complex decisions. However, we must remember that our professional practice must be framed in the 'patients' values, therapeutic proportionality, and assertive communication that allows for establishing therapeutic times and ceilings, which allows us to offer the best for patients and their families, remembering that everything that can be done on many occasions is not all that should be; and remembering the principles of beneficence and non-maleficence.

For a person's dying process to be what we all want, a process free of avoidable suffering, a series of elements are therefore required that are built during the patient's vital trajectory. Where the patient, the family, health professionals, and the health system are part of the responsibility

text in

text in