Remark

| 1) Why was this study conducted? |

| As suggested by Chiu et al., it is important to conduct research studies to validate the FNA questionnaire in other contexts and age groups. |

| 2) What were the most relevant results of the study? |

| The factor analysis found five factors each with a high ordinal alpha (Caregiving and family interaction, social interaction and future planning, Economy and recreation, independent living skills and/or autonomy, Services related to disability). Of the 76 items, 59 were preserved, which had a factorial load greater than 0.40; and 17 were left out because they did not meet this requirement. |

| 3) What do these results contribute? |

| Concerning the concurrent validity, the families perceive that high need in social interaction and future planning and little support for the person with intellectual disability in this aspect. |

Introduction

In recent decades, intellectual or developmental disability 1 has been understood from its familiar and social construction rather than from an individual perspective. The family, as the main social environment for people with disabilities 2-4, represents the greatest impact in more profound intellectual disability cases (5. This impact is evidenced by the appearance of greater, new, and specific needs, and the consequent affectation of the family’s quality of life satisfaction 6. Thus, providing support to family members according to the needs of the family nucleus is of the essence to achieve higher levels of satisfaction in the quality of individual and family life 7-8. An estimated one billion people of the world’s population live with disabilities 9 and just over a million in Colombia 10. According to the Association of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD), intellectual or cognitive disability is characterized by limitations in intellectual functioning (reasoning, learning, and problem solving) and in adaptive behavior comprised of a wide range of social and practical skills 11. Although biomedical, psychoeducational, sociocultural, or legal perspectives have been adopted to conceptualize a disability, researchers have proposed a more holistic approach to understand intellectual disabilities 12. In their view, this approach has many advantages in addressing a disability as it seeks to improve communication between professionals and those who assist the person with intellectual disabilities and their family and friends. The approach considers the risk factors and enables the combination of clinical supports required by persons with intellectual disability. Thus, to identify the needs in these and other aspects of families with adults with intellectual disabilities, according to the Colombian cultural context, the current study aimed to validate the psychometric properties of the adult version of the Family Needs Assessment (FNA) questionnaire for children with disabilities. The purpose was to determine its validity and reliability in Colombian families of adults with intellectual disability. As some studies suggest, self-report questionnaires are useful for their relevance in the measurement of variables and efficiency in data collection 13-14. Based on the identification of needs, the country’s programs, policies, and services on intellectual disability can be advised. The needs assessment can be useful for clinicians and researchers in the measurement and evaluation of the needs of families of people with intellectual disability. In this way, work with caregivers should be prioritized to increase their own quality of life and that of the family. For this reason, the current study aims at validating the FNA questionnaire, a component of an international research work in which the United States, Spain, Turkey, China, Taiwan, and Colombia participate.

Prior to this research study, validation studies of the Family Needs Scales for families of children with disabilities were carried our first in Taiwanese and later in Colombian families 15,16. The validation used an exploratory factor analysis to obtain the simplest, most coherent, and parsimonious structure. The resulting adjustment of the model was statistically significant and factors that accounted for the needs of these families were obtained. However, the adult version has not been validated, and there is scarce literature on instruments that assess the needs of families with adults with intellectual disabilities.

The design of the FNA questionnaire is based on the theory of the Family Quality of Life (FQOL) Model according to which the quality of life of people with intellectual disabilities is related to three factors: support, services, and individual and family practices. These factors account for values, policies, and programs or the resources and strategies that seek to promote the development, education and well-being of the person and their individual functioning. Additionally, demographic variables of the person with a disability such as age, income, ethnicity, and other characteristics such as health and behavior are considered along with the characteristics of the family including family cohesion and adaptability. These elements can generate new strengths for the family, needs and priorities that reorient the family's life cycle 17).

In respect of the main antecedents 15,16, the evaluation of the needs of families of people with disabilities through various psychometric instruments has had limitations in terms of comprehensibility, accessibility, contemporaneity, and cultural appropriation. Specifically, comprehensibility refers to the difficulty to understand the content of questions due to their reduced number produced by the factor analysis. Accessibility refers to the difficulty in the availability of psychometric instruments for families and professionals. Contemporaneity implies the absence of instruments that respond to the new family needs. Cultural appropriation implies the difficulties of translation according to the linguistic and cultural context of each country.

Consequently, the study was guided by the question: is the adult version of the FNA questionnaire an instrument with a sufficient level of psychometric properties to be considered reliable and valid in the Colombian context?

Materials and Method

Participants

Main caregivers of adults with intellectual disabilities, residing in the most representative cities in Colombia took part of the study. Due to the limited statistical and reliable information on people with intellectual disabilities, the distribution of the sample was determined from the reports of the Registry for the Location and Characterization of people with Disabilities provided by the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE). Participants consisted of 450 caregivers from various cities of the country: Bogotá (206), Medellín (34), Cali (134), Barranquilla (13), Ibagué (32), Bucaramanga (15) and Manizales (16). They were convened through contact with public and private institutions and service providers for people with intellectual disabilities. Caregivers lived in the same house, only some were not related to the adults. The exclusion criterion was the people who, despite living with the adult with intellectual disabilities, were no aware of the needs of the families. The diagnosis of intellectual disability was issued by the National Council on Disability in Colombia, through an Intellectual Quotient (IQ) test. Three groups were created to determine the participants’ monthly economic income: (1) Income lower than one minimum wage in Colombia (737,717 COP) (2) Income between one and four minimum wages (3) More than four minimum wages.

Instruments

The FNA questionnaire designed by a multinational team of researchers was used. The children version was previously validated in Taiwanese families 17. The instrument seeks to identify the needs of families with a person with intellectual and developmental disabilities in 11 areas related to family functioning: (1) Family relationships; (2) Emotional health; (3) Health; (4) Economy; (5) Social relations; (6) Free time; (7) Spirituality; (8) Daily care; (9) Teaching; (10) Access to services and (11) Changes throughout life. The original scale is made up of 76 Likert- type items ranging from 1 (no need) to 5 (very high need).

The Family Life Quality Scale (FLQS) version validated in Colombia was also applied 18 to carry out the concurrent validation. The scale consisted of 41 Likert-type items distributed into five factors: (1) Health and spirituality; (2) Interpersonal relationships and future planning; (3) Economy and free time; (4) Independent living skills and autonomy, and (5) Support for people with disability. The response options ranged between 1 (low satisfaction) and 5 (high satisfaction) with the quality of family life. The scale factors obtained alphas above 0.95.

Procedures

Participants were recruited from different institutions to where adults with intellectual disabilities belonged. They convened one morning to be informed about the objectives of the research, and the confidential and anonymous treatment of their information according to the regulations and ethical principles for research involving people in Colombia. Subsequently, the main caregivers of the children signed the informed consent and their questions about the study were addressed.

For the FNA validation process, firstly the linguistic adaptation of the items was carried out according to the Colombian context. For this purpose, the instrument was submitted to the evaluation of 10 expert judges (linguists, experts in the subject of disability and relatives of people with disabilities) in the criteria of quality, pertinence, and relevance 19. Secondly, cognitive interviews were conducted with five main caregivers of adults with disabilities to obtain qualitative information that corroborated their validity and reliability 14,20.

Thirdly, a pilot test of the FNA was applied to a sample of 20 participants to obtain social validation, as well as feedback from participants about the length, usefulness, and relevance of the scale 21. Some general statistical analyzes were run.

Statistical Analyses

The responses of the participants were processed with the Qualtrics software and then exported to the SPSS program.

The analysis of the psychometric properties of the FNA questionnaire started with the confirmation of whether the empirical structure of the scale corresponds to the theoretical one in the Colombian context; for this, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used, through the structural equation model (MES). The Maximum Likelihood estimator SAS 9.4 was used with the principal component extraction method.

Prior to the exploratory factor analysis, the KMO, Bartlett's test of sphericity and the determinant were estimated. The first two sought to question the feasibility of carrying out the factorial analysis, and the third made it possible to verify the absence of multicollinearity among the different factors of the scale 22. In the total sample, the calculation of the factorial model was based on two basic principles: (1) parsimony; the factorial solution must be simple and made up of the least possible number of factors or components. (2) The need for the extracted factors to be statistically significant and susceptible to substantive interpretation 23.

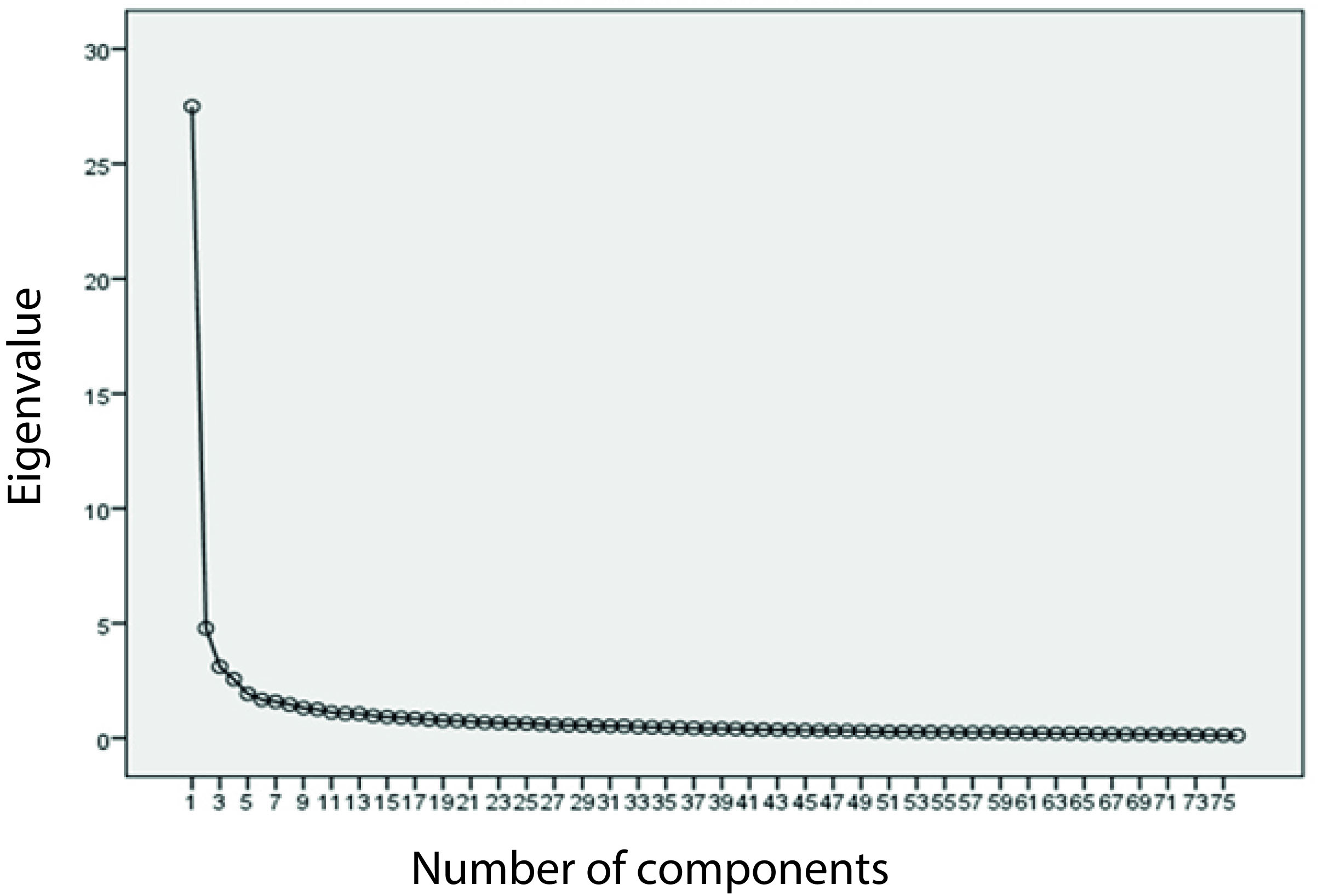

Considering that the confirmatory analysis did not show a good adjustment of the theoretical model of the 11 factors initially proposed, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted to elucidate a structure pertinent to the Colombian context. For this purpose, the criteria of parallel analysis 24, sedimentation graph, eigenvalue greater than 1.0 25 and interpretability of the result were used. Parallel analysis generates eigenvalues from a random data matrix, but with the same number of variables and cases as the original matrix. The eigenvalue of each factor in the real data is contrasted in a graph with the eigenvalue of the random data. To decide the number of factors, the eigenvalue of the real data with a magnitude higher than the eigenvalue of the simulated data is identified.

The reliability analysis of the questionnaire was carried out through Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the subscales. High internal consistency was considered for values higher than 0.8 26. Finally, the concurrent validity was estimated through the analysis of covariation between the FNA adult version and the ECVF. Theoretically, high family needs are related to low satisfaction scores in the quality of family life.

Results

Initially, some preliminary analyzes of the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants were made. Regarding the person with disabilities, their ages ranged from 18 to 76 years (M= 28.42; SD= 12.28). Table 1 shows detailed information of these data.

Table 1 Sociodemographic data (N= 554)

| n | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender Identity of the disabled adult | ||

| Male | 298 | 53.8 |

| Female | 256 | 67 |

| Age of the disabled adult (years) | ||

| 18-25 | 293 | 53.1 |

| 26-40 | 185 | 33.3 |

| <40 | 74 | 13.3 |

| No record | 2 | 0.3 |

| Degree of disability | ||

| Mild | 210 | 37.9 |

| Moderate | 196 | 35.4 |

| Severe | 43 | 7.8 |

| Profound | 19 | 3.4 |

| Does not know/Does not respond | 86 | 15.5 |

| Care provider type | ||

| Father (biological parent, stepfather, adoptive parent, foster care) | 65 | 11.7 |

| Mother (biological, stepmother, adoptive mother, foster care) | 332 | 59.9 |

| Brother | 51 | 9.2 |

| Sister | 74 | 13.4 |

| Grand parents | 5 | 0.9 |

| Other relative | 19 | 3.4 |

| Other unrelated person | 8 | 1.4 |

| Employment status of the caregiver | ||

| Full time job | 145 | 26.2 |

| Part time job | 143 | 25.8 |

| Unemployed | 86 | 15.5 |

| No formal job (father/mother/home caregiver, retired, disabled) | 180 | 32.5 |

| Monthly family income | ||

| Less than $737.717 | 118 | 21.3 |

| Between $737.717 to $1.475.434 | 136 | 24.5 |

| Between $1.475.435 to $2.213.151 | 61 | 11.0 |

| Between $2.213.152 to $2.950.868 | 61 | 11.0 |

| Above $2.950.868 | 178 | 32.1 |

| City | ||

| Bogotá | 321 | 57.9 |

| Bucaramanga | 16 | 2.9 |

| Barranquilla | 9 | 1.6 |

| Ibagué | 31 | 5.6 |

| Cali | 128 | 23.1 |

| Medellín | 33 | 6.0 |

| Manizales | 16 | 2.9 |

Confirmatory factor analysis of the original del FNA structure

The statistics related to the adjustment of the structural equation model (SEM) for the original structure of the FNA consisting of 11 factors, showed a low adjustment of the model to the data: the correlation matrix of the latent variables (factors) turned out to be singular hence, it was necessary to identify a new model suitable to the Colombian context. The CIF= 0.6494 was not higher than the reference value 0.95 and the TLI= 0.668 was not higher than the reference value 0.90 either.

Accordingly, the hypothesis of these models is rejected, and it is considered that the original structure of the FNA with 11 factors presents a low adjustment to the Colombian context, for this reason, we sought to carry out a further exploration of the structure of latent variables and items that suit the data.

Exploratory factor analysis of the original del FNA structure

Prior to the exploratory factor analysis (EFA), the KMO was 0.957 and the Bartlett sphericity test was Ji 2 (2,850) = 29,980.89; p <0.001. These results show that the feasibility of carrying out the factor analysis is required. Similarly, the determinant of the correlation matrix was <0.001, indicates the absence of multicollinearity between the factors. The correlation matrix between each item and the total scale are shown in Table 3.

To perform the factorial analysis the Promax rotation was used, the questions that had loads higher than 0.40 were selected and 17 items that had a lower factorial load were eliminated (#4, #5, #6, #17, #20, #37, #42, #50, #55, #58, #59, #61, #63, #68, #69, #73 and #74). Among the 59 items that were kept, 12 of them (#2, #3, #13, #26, #33, #35, #40, #57, #60, #62, #65, and #75) had factorial charges above 0.40 in more than one factor, these were located in the factor with the highest factorial load. The AFE initially yielded 13 factors, however, when examining the correlation matrix and the items retained, we decided to keep 5 of them because in factors 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 13 there were no questions with factor load above 0.40 (Table 3).

The results obtained in the model were grouped in 5 factors that explained 52.5% of the variance. Factor 1, Care and family interaction, accounted for 36.2% of the variance and was made up of 17 items that refer to activities related to the health care of the person with disabilities and situations and contexts where family members interact. Factor 2, Social interaction and future planning explained 6.3% of the variance represented in 11 questions related to different social activities developed by family members and others related with the planning of issues about the future of the person with disabilities. Factor 3, Economy and recreation, accounted for 4.1% of the variance and is made up of 9 items related to obtaining financial resources for current needs and those related to recreation. Factor 4, Independent living skills and autonomy, explained 3.4% of the variance and contains 8 items that assess the daily care activities that the person with a disability must do on their own and how to teach them to perform such activities. Factor 5, Disability Related Services, accounted for 2.6% of the variance, with 14 questions measuring needs related to requesting and managing disability-related services. Table 3 shows the questions for each factor and their factorial weights.

For all the factors, it was identified that the standard alpha tends to be biased downwards, these results are consistent with what was expected from ordinal Likert-type scale variables. Since each factor evaluates different dimensions and because there is no evidence that it is a two-factor model (Table 2), the ordinal alpha 27) instead of the total alpha of the scale is reported.

Table 2 Ordinal alpha and standard alpha of each of the factors.

| Factor | standard α | ordinal α |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Care and family interaction | 0.93 | 0.94 |

| 2. Social interaction and future planning | 0.89 | 0.91 |

| 3. Economy and leisure time | 0.85 | 0.89 |

| 4. Independent living skills and autonomy | 0.89 | 0.93 |

| 5. Disability-related services | 0.92 | 0.94 |

Regarding the identification of the dimensionality of the data, 8 factors were identified in the exploratory analysis and Kaiser’s criterion of eigenvalue greater than 1.0. However, the sedimentation plot showed the presence of 5 factors, which was also corroborated by the parallel analysis (Figure 1) where 5 dimensions are identified. Likewise, the analysis of the factor loadings (Table 3) shows a better interpretability of the results as these were grouped under the five dimensions orderly presented as Family care and interaction, Social interaction and future planning, Economy and recreation, Independent living skills and/or autonomy, and Disability-related services.

Table 3 Factorial weights by factors, correlation between items and total score.

| Factors | Factorial weights | Inter-item correlation and total score |

|---|---|---|

| Factor 1. Care and family interaction | ||

| 1. Medical control | 0.53 | 0.57** |

| 8. Clear understanding of the strengths and needs of each person in my family. | 0.72 | 0.50** |

| 9. Hope for the future of the people in my family. | 0.61 | 0.55** |

| 10. Be part of a religious or spiritual community that includes people in my family. | 0.68 | 0.54** |

| 11. Be able to afford basic needs. | 0.49 | 0.64** |

| 12. Make it easier for the doctors who treat us to talk to each other about our case. | 0.50 | 0.62** |

| 19. Talk about feelings, opinions, and goals with everyone in my family. | 0.81 | 0.56** |

| 21. Teach spiritual or religious beliefs to my child(ren). | 0.63 | 0.52** |

| 23. Ensure good vision and eye care. | 0.55 | 0.59** |

| 30. Solve problems together | 0.83 | 0.55** |

| 31. Promote the self-esteem of each person in the family. | 0.58 | 0.64** |

| 32. Rely on religious or spiritual beliefs to understand the difficulties of the people in my family. | 0.61 | 0.62** |

| 41. Have close emotional ties between family members. | 0.80 | 0.56** |

| 44. Take proper dental care. | 0.55 | 0.61** |

| 48. Teach safety rules at home and elsewhere. | 0.51 | 0.64** |

| 53. Get enough sleep. | 0.44 | 0.62** |

| 56. Maintain a trust relationship with all the professionals who care for my family. | 0.42 | 0.66** |

| Factor 2. Social interaction and future planning | ||

| 3. Participate in preferred indoor fun activities in the community. | 0.65 | 0.54** |

| 7. Plan higher education of the people in my family. | 0.42 | 0.41** |

| 14. Participate in preferred fun activities that take place in open spaces in the community. | 0.57 | 0.64** |

| 15. Help people in my family to relate to others. | 0.52 | 0.61** |

| 18. Plan career guidance services. | 0.51 | 0.46** |

| 26. Make it easy for people in my family to make friends. | 0.73 | 0.54** |

| 27. Plan a successful passage from secondary education to adult life for the people in my family. | 0.67 | 0.45** |

| 28. Know when my family members are making progress in their learning. | 0.45 | 0.58** |

| 36. Carry out relaxing activities at home. | 0.49 | 0.64** |

| 38. Develop long-term goals for family members. | 0.61 | 0.61** |

| 39. Teach others to make decisions and solve problems. | 0.47 | 0.62** |

| Factor 3. Economy and recreation | ||

| 16. Change the place of residence (moving). | 0.43 | 0.40** |

| 22. Have the necessary resources to pay support staff. | 0.71 | 0.53** |

| 25. Go on vacation with the family. | 0.58 | 0.63** |

| 29. Have leisure time or vacation. | 0.55 | 0.67** |

| 34. Ensure adequate hearing health. | 0.57 | 0.59** |

| 40. Access the necessary services. | 0.46 | 0.67** |

| 43. Save for the future. | 0.55 | 0.62** |

| 54. Take a break in the attention or care of the child. | 0.46 | 0.59** |

| 62. Have adequate transportation. | 0.41 | 0.61** |

| Factor 4. Independent living skills and autonomy | ||

| 2. Practice self-care activities. | 0.79 | 0.60** |

| 13. The disabled person in my family needs support to go to the bathroom. | 0.87 | 0.48** |

| 24. Help to take the medication. | 0.65 | 0.52** |

| 33. Pay for special therapies, equipment, or special food (adapted light switches, behavioral support, gluten-free products) for the person with a disability. | 0.53 | 0.59** |

| 35. Find and use special resources to facilitate communication and daily living of the whole family with the person with disabilities. | 0.50 | 0.64** |

| 57. Teach the person with a disability independent living skills. | 0.67 | 0.62** |

| 65. Teaching the person with a disability to use the bathroom. | 0.84 | 0.55** |

| 75. Teaching the person with a disability to maintain or improve motor skills. | 0.82 | 0.56** |

| Factor 5. Disability Related Services | ||

| 45. Manage healthcare support. | 0.57 | 0.63** |

| 46. Know how to act in situations and negative attitudes of others. | 0.46 | 0.62** |

| 47. Plan the future for when I can no longer take care of the people in my family. | 0.62 | 0.58** |

| 49. Follow up on the services my family receives to find out if they really benefit us. | 0.52 | 0.67** |

| 51. Face the challenges of each person in the family. | 0.44 | 0.61** |

| 52. Get a job or keep it. | 0.45 | 0.60** |

| 60. Request aid from the government and, if it is the case, deal with its negative response. | 0.65 | 0.56** |

| 64. Find healthcare support when needed. | 0.68 | 0.65** |

| 66. Know and defend the rights of the people in my family to not be discriminated against. | 0.63 | 0.65** |

| 67. Prevent the use of psychoactive substances and other addictions. | 0.51 | 0.59** |

| 70. Find ways to have the information needed to make good decisions about services. | 0.52 | 0.73** |

| 71. Feeling informed and helped by the professionals about the advances (improvements) and difficulties that my child(ren) present(s). | 0.50 | 0.66** |

| 72. Teach the people in my family appropriate social behaviors. | 0.45 | 0.63** |

| 76. Guide the person with disabilities to have appropriate sexual behavior. | 0.72 | 0.43** |

**p<0.01

The 76 needs were combined to obtain 5 scales from the averages of the corresponding items, this can be used later in research projects that seek to assess the needs of families with adults with intellectual disabilities. However, prior to implementation, a confirmatory analysis that validates this result (Figure 1) is suggested.

Figure 1 Sedimentation of the exploratory factor analysis for the FNA instrument comprising 77 items (N= 554).

Concurrent validity was examined in terms of covariation among adult FNA factors and their total score, and Family Quality of Life Scale (FQLS) factors and their total score. The results obtained yielded no negative (as expected) or significant correlations between any of the factors, nor with the total scores. Only the Social interaction and planning for the future factors correlated with CV of support for the person with disabilities (-0.15; p <0.05), that is, the greater the need for social interaction and planning for the future, the more the families experience a lower quality of life in support to the person with disabilities (Table 4).

Table 4 FNA and CV Inter-factor correlation

| Factors | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. FNA Care and family interaction | - | 0.62** | 0.70** | 0.50** | 0.75** | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | -0.07 | -0.05 | -0.03 | 0.89 |

| 2. FNA Social interaction and Planning for the future | - | 0.58** | 0.42** | 0.73** | -0.03 | 0.07 | -0.02 | -0.03 | -0.15* | 0.81** | -0.06 | |

| 3. FNA Economy and Recreation | - | 0.65** | 0.66** | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | -0.02 | -0.11 | 0.83** | -0.04** | ||

| 4. FNA Independent living skills and Autonomy | - | 0.47** | 0.7 | 0.01 | 0.06 | -0.05 | -0.06 | 069** | -0.01 | |||

| 5. FNA Disability related services | - | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.04 | -0.07 | 0.89** | 0.2 | ||||

| 6. CV Family interaction | - | 0.63** | 0.55** | 0.48** | 0.46** | 0.01 | 0.80** | |||||

| 7. CV Parental rol | - | 0.45** | 0.35** | 0.34** | 0.07 | 0.70** | ||||||

| 8. CV Health and Security | - | 0.71** | 0.64** | 0.03 | 0.85** | |||||||

| 9.CV Family resources | - | 0.61** | -0.04 | 0.79** | ||||||||

| 10.CV Support for people with disabilities | - | -0.10 | 0.79** | |||||||||

| 11. Total FNA | - | -0.03 | ||||||||||

| 12. Total CV | - |

* p <0.05; **p <0.01

Finally, the average scores of the 5 factors of the Colombian FNA for adults were estimated (Table 5). The factor showing the highest level of need according to the responses of the participants was the Disability-related Services factor, in contrast to the Independent Living Skills and/or Autonomy factor, where participants reported the lowest level of necessity.

Table 5 Descriptive information of factors (N= 554)

| Factor | Cronbach’s alpha | M(DE) | Need order | Number of items |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Care and Family interaction | 0.93 | 3.25 (0.90) | 4 | 17 |

| 2. Interaction and Future planning | 0.89 | 3.39 (0.90) | 2 | 11 |

| 3. Economy and Recreation | 0.85 | 3.31 (0.90) | 3 | 9 |

| 4. Independent living skills and Autonomy. | 0.89 | 2.47 (1.13) | 5 | 8 |

| 5. Disability related services. | 0.92 | 3.66 (0.87) | 1 | 14 |

Discussion

This study evaluated the needs of families with disabled adults, which allowed their identification and can consequently allow the generation of public and private strategies, adequate to satisfy them.

The evaluation of the psychometric properties of the FNA adult version evidenced the validity and reliability of the 59 items retained. According to the responses of the participants, the family needs identified were grouped into five factors that accounted for 52.5% of the variance, in contrast to the results obtained in the validation of the FNA version for children 15, which was grouped into four factors that accounted for 49.6% of the variance.

Although the factors were grouped differently in each version of the scale, some of these contained similar items, specifically, when comparing the factorial structure of the adult version generated by the FNA with that of the children version. The Care and Family Interaction factor retained 14 items from the Services related to disability factor. Conversely, the Social Interaction and Future Planning factor retained 6 items from the Social and Family Interaction factor. On the other hand, the Economy and Recreation factor retained four items from the Economy and Future Planning factor; similarly, the factor Services related to the disability of the scale of adults retained six items of the factor Services related to the disability of the scale of children. Last, the Independent Living Skills and Autonomy factor grouped six items from the Care and Teaching factor.

Within the final five factors of the adult version of the FNA, the participants reported that the highest family needs are concentrated in the Services factor related to disability. This result is consistent with the findings of other studies of families with adults with disabilities that have shown the need for specialized support and services that respond to the gaps of the social protection system, health services, and the lack of labor inclusion opportunities 3,28-30. On the other hand, the parents, and caregivers of adults with disabilities reported that the least critical needs were those of the independent living skills and autonomy factor, as shown in the results of other studies carried out in Colombia, most people with disabilities upon reaching adulthood have managed to develop these skills. However, their main needs are related to ignorance of their rights, scarce support, and few opportunities to access social and labor inclusion 31-33.

Regarding concurrent validity, correlations were made between the five factors obtained from the FNA adult version with the factors of the ECVF. The proposed hypothesis was that there should be a negative correlation between each of the factors of one scale with the other, as well as a correlation with the total score of the scales. In other words, a low score in the dimensions of family needs should be correlated with a high score in the dimensions of family quality of life. However, the results obtained contradicted the hypothesis because there were no factors correlated with any other, nor with the total points of the scales excluding, the Social interaction and planning for the future factors that correlated with the support for the person with a disability factor of the ECVF.

According to the validation study of the FNA version for children in Colombia 15 and the validation of the FNA in Taiwan 16, the absence of a correlation between the two scales can be explained by the difficulties inherent in measuring these constructs, and because the measurement could be biased by a subjective perception of the level of need and its relationship with the level of life quality. In other words, although families may not have their needs really satisfied, the fact of having identified the support they require to satisfy them may lead them to believe that they have a high quality of family life to the extent that they could potentially be able to satisfy them.

On the other hand, regarding the factors that correlated, this association can be explained in the fact that adults interact with others and make plans when they work, organize social events, buy a home, among others. This leads to having a positive effect on their quality of life and that of their family, as reported by Cabrera et al. 34. However, this type of social interaction requires even greater legal support in Colombia, since only few organizations and public and private companies promote this type of inclusion for adults with intellectual disabilities.

A potential limitation to the current study is that access to adults with disabilities was only available when they were linked to a private or public institution. This may leave individuals and families with a high level of vulnerability and high family needs out of the sample, which would mean that the results obtained are underestimated for this sample. Likewise, the needs of families with adults with disabilities in other Colombian cities that are not main cities and that were not part of the study, should be considered.

In conclusion, the Colombian version of the FNA adults found five factors with a high ordinal alpha that must be corroborated through a confirmatory factor analysis, both as an instrument suitable for the Colombian context, and to establish its clinical applications. Regarding concurrent validity, families perceive a high need for social interaction and planning for the future and little support to the person with intellectual disabilities in this respect.

texto em

texto em