Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

AD-minister

Print version ISSN 1692-0279

AD-minister no.27 Medellín July/Dec. 2015

https://doi.org/10.17230/ad-minister.27.2

ARTÍCULOS ORIGINALES

DOI: 10.17230/ad-minister.27.2

Tax incentives and investment expansion: evidence from Zimbabwe's tourism industry

Incentivos fiscales y expansión de las inversiones: la industria del turismo en Zimbabue

Watson Munyanyi1 Campion Chiromba2

1 Full time Lecturer in the Department of Banking and Finance at Great Zimbabwe University, Masvingo, Zimbabwe, E-mail: wmunyanyi@gzu.ac.zw or wmunyanyi@hotmail.com

2 Department of Banking and Finance Lecturer at Great Zimbabwe University, Masvingo, Zimbabwe. E-mail: cchiromba@gzu.ac.zw/ or cchiromba@gmail.com/

Received: 10/09/2015 Modified: 03/11/2015 Accepted: 23/11/2015

JEL: L83, H25,

Abstract

This paper investigates the effects of tax incentives on investment growth in the tourism sector in less developed countries, using Zimbabwe as the case study. The study was prompted by the realisation that many less developed countries use tax incentives as means for luring investors into their countries yet there is a general lack of analysis on whether such tax incentives have any impact on social and capital growth. The study employed face-to-face and telephone interviews with key stakeholders in the tourism sector that were selected through stratified and random sampling methods. Questionnaires, distributed by hand, post and email were also used in situations where interviews were not feasible. Secondary data was used as a bedrock for detailed analysis. The paper established that most policy makers indeed use tax incentives to lure investors into the tourism industry but such policies are not followed by other supportive policies in other areas of the economy that help boost investment in the tourism sector. Other factors like corruption, transparency in government policies, length and cost of starting a business in the country, for instance, are other important factors that need to be taken into consideration. Among other recommendations there is a need for political stability, consistent and supportive policy, limited government interference in the industry, decentralization and opening up of more local and foreign tourism promotion centres, application of low tax rates across industries and the general creation of a favourable environment for the effectiveness of tax incentives.

Keywords: tourism investment, tax incentives, economic growth, tourism.

Resumen

Este trabajo investiga los efectos de los incentivos fiscales sobre el crecimiento de las inversiones en el sector del turismo en los países menos desarrollados, utilizando Zimbabue como estudio de caso. El estudio fue motivado por la constatación de que muchos países subdesarrollados utilizan incentivos fiscales como medio de atraer a los inversores en sus países, sin embargo todavía existe una carencia general de análisis para determinar si este tipo de incentivos fiscales tienen algún impacto en el crecimiento social y del capital. El estudio empleó entreviste en persona y por teléfono con los principales interesados del sector turístico, los cuales fueron seleccionados a través de un muestreo estratificado y métodos aleatorios. También se utilizaron cuestionarios distribuidos en persona, por correo postal y por correo electrónico en situaciones en las entrevistas no eran factibles. Los datos secundarios se utilizaron como fundamento para el análisis detallado. En el documento se establece que la mayoría de los responsables políticos sí utilizan incentivos fiscales para atraer a los inversores en la industria del turismo, pero estas políticas no son seguidas por otras políticas de apoyo en otras áreas de la economía que ayuden a impulsar la inversión en el sector turístico. Otros factores como la corrupción, la transparencia en las políticas gubernamentales, la duración y el costo de iniciar un negocio en el país, entre otros, son diferentes factores importantes que deben ser tomados en consideración. Entre otras recomendaciones se encuentra la necesidad de una estabilidad política, una política coherente y de apoyo, la interferencia limitada del gobierno en la industria, la descentralización y la apertura de los centros locales y extranjeros de promoción turística, la aplicación de tipos impositivos bajos en todos los sectores y la creación general de un entorno favorable para la efectividad de los incentivos fiscales.

Palabras clave: inversión turística, incentivos fiscales, crecimiento económico , turismo.

Introduction

"Travel &Tourism's impact on the economic and social development of a country can be enormous; opening it up for business, trade and capital investment, creating jobs and entrepreneurialism for the workforce and protecting heritage and cultural values", World Travel & Tourism Council Economic Impact Report (2015). According to the same report, Travel & Tourism generated US$7.6 trillion (10% of global GDP) and 277 million jobs (1 in 11 jobs) for the global economy in 2014, a number that, according to World Travel & Tourism Council (2013), could even rise to one in ten jobs by 2022. The direct contribution of Travel & Tourism to GDP was USD 2,364.8 billion (3.1% of total GDP) in 2014, and is forecast to rise by 3.7% in 2015, and to rise by 3.9% per annum, from 2015-2025, to USD3,593.2bn (3.3% of total GDP) in 2025, WTTEI (2015). Recent years have seen Travel & Tourism grow at a faster rate than both the wider economy and other significant sectors such as automotive, financial services and health care.

The tourism industry is an industry that is difficult to define. This is due to the fact that everything in a country can potentially feed into the tourism chain. This paper defines tourism industry as a variety of different actors, including hotels, air carriers and transport companies, tour operators, travel agents, rental agencies, and countless suppliers from other sectors, Corthay and Loeprick (2010).

Tax, in most countries, is the main source of government income. According to Heritage Foundation Report (2012), tax in Zimbabwe contributes 49.3 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), in South Africa it contributes 26.9 percent whilst in the USA it also contributes 26.9 percent of GDP. This shows that in Zimbabwe tax contributes a very large chunk of income towards its $10.81 billion fiscal budget, according to World Bank Country Data (2013). In Jamaica, tourism accounts for 19.5 per cent of GDP, 20.4 per cent of government revenues, 25 per cent of jobs and 50 per cent of exports, Brown (2012). The fact that tax is the main source of government income implies that the government can show its commitment towards the growth of a particular sector by foregoing this income in exchange for increased investments. In Zimbabwe, the tourism industry is ranked third in terms of income generation after mining and agriculture industries, hence the need to strengthen this sector. According to Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Fact-book (2012) figures, Zimbabwe's service sector fixed capital investment as a percentage of GDP was 21.9 percent; the tourism industry contributed 54.6 percent towards GDP whilst it employed 24 percent of total population.

Tax incentives refer to a deduction, exclusion, or exemption from a tax liability, offered as an enticement to engage in a specified activity such as investment in equipment goods for a certain period, Smith (2003). Clark, Cebreiro and Bohmer (2007) define tax incentives as those special exclusions, exemptions, deductions or credits that provide special credits, a preferential tax treatment or deferral of tax liability. The concept of tax incentives is being used widely in the fiscal policies of many developed and developing countries to stimulate investment growth. Over the past four decades, state investment tax incentives have proliferated in the developed and developing countries. After noticing a continuous decline in the tourism industry, in terms of both investment and visitors, the Zimbabwean government introduced tax incentives for this industry in 2009. The incentives were aimed at boosting investment and visitors influx in the tourism sector.

This paper aimed at analysing the impact of tax incentives in developing countries based on the case of Zimbabwe. The main objective was to establish whether tax incentives introduced by the Zimbabwean government in the tourism industry had any impact on social and capital growth in terms of equipment expansion, revenue generation, job creation and positive externalities in the industry. The study was carried out in full view of the fact that whilst it is difficult to quantify these elements due to lack of sufficient databases, trying to do so provides a useful conceptual tool for policymakers analysing the general framework for incentives as well as targeted incentives for anchor investments, export-oriented and mobile investments, extractive industries, and so on, James (2009).

It is understood that whilst every tax incentive has potential costs and benefits, the benefits must outweigh the costs for an incentive to be approvable and productive. Costs are mainly in the form of revenue losses from investments that would have been made even without the incentives, indirect costs such as economic distortions, administrative and leakage costs, James (2009).The analysis of costs, however, was beyond the scope of this paper. For assessment purposes, this paper took the stance that a tax incentive must generate a noticeable long term investment and revenue generation in addition to increased job creation and positive externalities.

Literature Review

After rising during the 1990s, reaching 1.4 million tourists in 1999, industry figures registered a 75% fall in visitors to Zimbabwe by December 2000, with less than 20% of hotel rooms occupied. While addressing delegates at the Safari Operators Association of Zimbabwe's annual general meeting in Bulawayo in 2006, Morris Mpofu, Reserve Bank Zimbabwe Division Chief (Exchange Control) said the receipts from safari hunting dropped by 45 percent between 2004 and 2005 to US$19,1 million. Such a fall can be traced back to the controversial land reform programme which started in the year 2000 as the Zimbabwean tourism industry suffered a great setback with tourists from the European Union and America shunning Zimbabwe as a tourism destination (BBC In-depth, 2003)1. Byo24News (2011)2 also quotes a tour operator, Ben Tessa, as saying Zimbabwe is now portrayed as a high risk destination, and international media have been warning travellers to visit Zimbabwe at their own risk.

In 2007, the World Economic Forum (WEF) index ranked Zimbabwe as one of the outposts of unattractive travel and tourism destinations alongside Bolivia and Burkina Faso. Zimbabwe was ranked 107 out of 124 countries, further dropping to 117 according to the Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report released in March 2008. Tourism Authority's publicity campaigns to save the country's battered tourism sector including the "Come to Victoria Falls" campaign initiated in 2002 and the "Look East" policy initiated in 2003 saw very little success due to negative publicity from international media.

WEF Travel & Tourism Competitiveness (TTC) Index for 2013 notes that Zimbabwe is ranked 118 out of 140, up from 119 out of 139 in 2011 and 121 in 2009, indicating a general improvement in terms of world competitiveness. It was also ranked number 15 out of 31 in Sub-Saharan Africa. However, the policy environment continues to be among the least supportive of travel and tourism industry development in the world (ranked 138th), with extremely poor assessments for laws related to Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and property rights. Furthermore, starting a business is extremely time consuming and costly. The tourism sector has been operating without a guiding policy framework, (USAID, 2013). The National Tourism Policy compiled by the Ministry of Tourism and Hospitality Industry was adopted by the Cabinet in August 2012. The ministry's Strategic Plan 2013-2015 also remains greatly on paper, with very little being implemented on the ground.

On November 5, 2010, at the Hospitality Investment Conference Africa (HICA) in Johannesburg, Dr Sylvester Mauganidze, Permanent Secretary to the Zimbabwe Tourism and Hospitality Ministry announced the incentives available for investors in the hospitality industry in Zimbabwe. These incentives are in the form of duty free imports, automatic work permits, permanent residence, and tax holidays for tourism investors. Also speaking at a discussion titled ‘Straight Talk Zimbabwe', Dr Mauganidze indicated that people investing US$500,000 would receive permanent residence, while those investing US$100,000 would automatically receive a work permit. All tourism related imports would be duty free while all investments would be tax free for the first five years. Investment incentives are mostly in the form of tax incentives namely: first 5 years of operation 0 percent taxable income of an operator, second 5 years of operation 15 percent, third 5 years of operation 20 percent, and thereafter normal rates of corporate tax apply, Zimbabwe Investment Authority (ZIA), Tourism Investment document.

Normal tax payable by Zimbabwean companies on their taxable income is at the rate of 25%. A 3% AIDs levy is imposed on the tax chargeable giving an effective tax rate of 25.75%.The tax is payable by both public and private companies as well as private business corporations, PKF International Tax Committee (2013).

Tax incentives are amongst the various policy instruments that governments use to fund or support the local industries. Tax incentives and other fiscal incentives are developed in the context of stimulating growth.

According to Africa Sun group Chief Executive Officer, the formation of the Government of National Unity (GNU) in February 2009 had an immediate positive effect on the tourism sector, Munyeza (2009), since travel warnings against Zimbabwe were lifted as the political and economic stability were restored. The commitment by the Zimbabwean Government towards the development of tourism sector led to Zimbabwe being selected to co-host the 20th session of the United Nations World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO) General Assembly in Victoria Falls in August 2013. Such developments came after the sector had been adversely affected by the effects of the hyperinflationary economic environment which had devastated the operators' ability to host tourists. It is against this background that the government unveiled a package of tax incentives to promote investment in the tourism industry.

According to Heritage Foundation (2013) Index, Zimbabwe's economic freedom score is 28.6, making its economy the 175th freest economy out of 176 countries. This score is in effect a result of a 2.3 points increase from the previous year, reflecting particularly strong improvement in control of government spending. The country is also ranked last out of 46 countries in the Sub-Saharan Africa region. During the period 2010 to 2012 (inclusive), Zimbabwe saw a general increase in tourist arrivals with an average increase of 15.1 percent and the highest percentage increase being in period 2012/2011 which saw a 26 percent increase, UNWTO (2013). During the same period the country saw an 18.14 percent increase in tourist receipts over the period 2012/2010.

Governments consider tax incentives as an instrument to encourage the development and growth of various targeted sectors in the economy. The reduction in the tax burden is meant to increase the propensity to inject capital investments thereby allowing operators to grow. The question is whether tax incentives stimulate investment growth in the tourism industry to the extent that is desired by policy formulators.

Use of Tax Incentives

The abundance of government tax incentives raises this important empirical question whether these tax incentives are effective in increasing investment and other forms of economic activity within a country. Fisher and Peters (1998) state that economic development incentives can probably influence firm location expansion decisions. In a survey paper, Wasylenko (1997) concluded that the elasticity of various forms of economic activity to tax policy "are not very reliable and change depending on which variables are included in the estimation equation or which time period is analysed", hence the need to determine the best fiscal intervention to boost investment. Cummins, Hasset and Hubbard (1996) postulate that governments tend to institute investment tax incentives when the aggregate investment is perceived to be low and remove them when aggregate investment is perceived to be high.Economists have long argued that significant reforms of corporate taxation can have large effects on firm's investment decisions. Cummins, Hasset and Hubbard (1996) have argued that around major tax reforms, the elasticity of investment with respect to the tax portion of the cost of equipment is remarkable in determining whether the tax incentive is cost effective or not. In support of the above assertion, Ahmed (1997) says that tax incentives are an alternative tool to providing financial assistance to an economic agent, by reducing their tax liability in the form of tax exemptions, tax allowances, tax credits and tax holidays thereby increasing the level of income available for spending on the acquisition, creation or enhancement - other than routine maintenance-, of fixed assets.

Buss (2001) on the contrary argues that tax incentives, job creation tax incentives and exemptions as well as machinery and equipment incentives are costly, ineffective and detrimental. He also argues that there is little risk to policy makers when incentives fail because the failure can be blamed on economists, market forces or dysfunctional corporate behaviour. Similar sentiments are raised by James (2009) who argues that countries typically pursue growth-related reforms by using a combination of approaches, including macroeconomic policies, investment climate improvements, and industrial policy changes—including investment incentives and if such reforms have led to growth, it is difficult to attribute it solely to tax incentives.

Tax Incentives and Investment

It is important to hasten to say that, according to Corthay and Loeprick (2010), a good investment climate for tourism, underpinned by a sound tax regime, can play a central role in a government's growth and development strategy. Further to this, Jorgenson (1963) confirmed that a direct relationship exists between tax concessions on one side and inflow of foreign direct investments and equipment investment expenditure growth on the other side. The neo-classical model, originally presented by Jorgenson (1963), argued that investment should be a function of expected future interest rates, prices and taxes (Clark, 1979). It assumes that the desired stock of equipment depends on planned output and the ratio of output price to impact rental price or services of equipment. Jorgenson's formulation asserts that equipment is accumulated to provide equipment services that are inputs to the productive process. In summary, Jorgenson's findings are that sustained tax cuts raise the amount of equipment available to firms, thereby improving their investment capabilities. Traditionally, tax policies increase the firms' ability to finance their projects by lowering costs through tax relief. The lower costs typically translate into higher investment levels, Hall and Jorgenson (1967).

Whitman (1975)supports the assertion by Hall and Jorgenson (1967). He says that when intelligently used, these incentives can increase the profitability, after tax, of investment in fixed assets, as well as reinforcing the cash flow needed to finance them. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2000) notes that while the efficacy of incentives as a determinant for attracting FDI is often questioned, countries have increasingly resorted to such measures in recent years. In particular, countries have been offering tax incentives to influence the location decisions of investors. Ngowi (2000) who studied tax incentive in Tanzania discovered that Tanzania grants a relatively generous package of tax incentives for foreign investors. He adds that the effectiveness of the incentives is questionable and it is a naked truth that the incentives are costs to the government as they represent lost government revenues.

Tax Incentives and Equipment Investment Growth

To define the term "equipment investment", Riley (2008) says, "to an economist it is a precise term which involves the acquisition of equipment goods designed to provide us with consumer goods and services in the future". Thus investment spending involves a decision to postpone consumption and to seek to accumulate equipment which can raise the productive potential of an economy. Equipment investment isthe expenditure incurred by a business entity to acquire, construct a property or asset during its course of business, wherein the benefits from such expenditure is enduring in nature and such investment are used for the better performance of the business activity, Cummins, Hasset and Hubbard (1996). The interaction of corporate income tax and international equipment flows suggests that the source-based equipment taxes potentially result in quite significant distortions in the allocation of equipment at international level, Fuest, Huber and Mintz, (2005).

Boehlje and Ehmke (1998) say that equipment investment decisions, which involve the purchase of land, machinery and building or equipment are the most important decisions undertaken by the manager. These decisions, according to Boehlje and Ehmke, involve the commitment of large sums of money and will affect the business over many years. Because funds are paid out immediately whereas the benefits accrue over time, it is imperative for the government to intervene and cushion the firms through tax incentives and concessions, Cummins, Hasset and Hubbard, (1996).

Although there appears to be confidence among policy makers that tax incentives can influence the investment decisions of firms, and serve as a tool for stabilizing the economy, Goolsbee (1997) argues that empirical evidence for the connection is weak. According to Goolsbee, econometric research has commonly found that tax policy and the cost of equipment have little effect on real investment. He adds that using tax subsidies as instruments for investment demand to actually estimate a supply curve for equipment goods puts the short-run elasticity at around 1, explaining the small estimated effects of tax policy on real investment. His conclusion was that for policy makers interested in using tax policy to stimulate investment or smooth the business cycle fluctuations, the results are not promising.

In agreement with Goolsbee; Zee, Stotsky and Ley (2002) argue that the only theoretical argument for relieving a firm from having to pay Value Added Tax (VAT) on inputs must be based on relieving it of a cash flow burden, thereby empowering it to make significant equipment investments.

Harvey and Gayer (2010) analysed the relationship between incentives and excess burden on demand for housing services. He noted that whilst an incentive3 increases consumer surplus, the increase is exceeded by the cost of the subsidy to the government, hence creating excess burden to the government. He concluded that the government is paying more than the benefit received by the housing consumers hence, according to Harvey, the subsidy turns out to be inefficient.

According to Bergsman (1999), in Ngowi (2000) many economists disdain tax incentives, seeing them as ineffective and a loss of revenue for the Treasury and as expensive distortions that actually reduce the true value of output. Tax incentives cause distortion in factor or product markets. On the other hand, most directors of foreign investment promotion agencies who are in favour of this and other incentives they come across, seek to take advantage of the distortions mentioned above.

International Tourism Incentives

As noted, a lot of countries around the world receive a significant percentage of their GDP from the tourism sector, which justifies the need to incentive the sector. It seems very little attention is paid to the question whether incentives provided to the tourism sector bare more costs to the government than the benefit received by the tourism operators or not, whether they ultimately attain the goals intended by the policy makers, or whether the accrued investments can be identified with tax incentives.

In Malaysia, tourism projects, including eco-tourism and agro-tourism projects, enjoy tax incentives. These include hotel businesses, construction of holiday camps, recreational projects including summer camps, and construction of convention centres with a capacity to accommodate at least 3,000 participants. Amongst the incentives given by the government are the Pioneer Status, in which a company granted such status enjoys a 5-year partial exemption from the payment of income tax (pays tax on only 30% of its statutory income); and Investment Tax Allowance in which a company granted such incentive gets an allowance of 60% of the qualifying capital expenditure incurred within five years from the date when the first qualifying capital expenditure is incurred.

In 2009, after seeing tourism grow remarkably in 2007, the Indian Tourism minister Selja requested the Finance minister to include tourism incentives in the July budget, after the country witnessed a sharp decline in tourists due to global economic slowdown, The Indian Express (2009). Among the incentives requested are tax incentives for the growth of tourism infrastructure, relaxation of import duties on adventure tourism equipment, export status for foreign exchange earned by inbound tour operators and de-linking hotels from real estate sector for the purpose of credit.

Tourism in Jamaica accounts for 19.5% of GDP, 20.4% of government revenue, 25% of jobs and 50% of exports. According to Sacks Adam (2012), the president of Tourism Economics, an Oxford Economics company, as quoted by Brown (2012), "tourism sector in Jamaica is more than pulling its own weight, as its tax contribution is greater than its GDP contribution hence the need to rationalize the sector in order not to do anything that will pull back on the tourism". Currently, the incentives offered to the industry are generally lower than those offered across the Caribbean. The value of the incentives to the tourism sector did not outweigh the tax revenue it earned between 2005 and 2007, which averaged 40 per cent. Thus there is a general fear that the tourism industry might opt to move to other Caribbean countries.

Shingi Munyeza, Group CEO of African Sun Hotels, indicated in 2010, at the company's annual general meeting, that there were some 6,266 hotel rooms in Zimbabwe with no additional rooms having been added in the last 11 years. In 1996, there were 45 air carriers flying into Zimbabwe from 100 international destinations and as of 2010 there were 11 carriers flying from fewer than 10 destinations with 95% percent of tourists entering Zimbabwe travelling from South Africa. Regionally, Zimbabwe supplies 16 percent of all hotel rooms, second to South Africa. The stagnation in the industry led the stakeholders to advocate for incentives in the sector, amongst which tax incentives.Van Parys and James (2010), in their paper entitled "The Effectiveness of Tax Incentives in Attracting FDI: Evidence from the Tourism Sector in the Caribbean", tested whether the neoclassical investment theory prediction according to which tax incentives raise investment by lowering the user cost of capital, holds in the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union (ECCU). They found out that tourism investment in Antigua and Barbuda after 2003 increased significantly more than investment in the other six regional countries due to the tourism tax incentives reform. James (2009), in his paper entitled "Incentives and Investments: Evidence and Policy Implications", revealed that on their own incentives have limited effects on investments; countries must also dedicate themselves to improving their investment climates. Similar perceptions were published by Nsiku and Kiratu (2009) in their study on sustainable development impacts of investment incentives using the Malawian tourism industry as a case study. They concluded that investment incentives do not determine Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in the tourism sector, suggesting that the type, nature and quantity of FDI in the tourism sector are shaped by other government policy such as promoting increased private sector participation rather than by investment incentives per se. These findings highlight an important factor of the interrelation between government policies.

In summary, according to both theoretical and empirical evidence and as quoted in Boura (nd), the effects of tax incentives on investment growth and foreign direct investment are mixed Veugelers (1991), small (Head et al, 1999) and even inexistent (Friedman et al, 1992). Their results show a myriad of effects from nation to nation and from time to time.

Research Methodology

The study reviewed relevant secondary data, such as regional and international tourism investment policies, travel and tourism competitive reports, investment reports, together with documented Zimbabwean policies mainly from ZTA and ZIA. Information from relevant studies was also reviewed. Whilst at times having a weakness of not being in tune with the study at hand, secondary data was useful in forming the background of the research and creating a framework for conducting other qualitative methods.

A sample of 80 representatives from tourism operators in Zimbabwe were selected as respondents to obtain primary data. Out of a 200 population estimate, the population was stratified into hotels, lodges, air carriers and transport companies, safaris, tour operators, travel agents and rental agencies. Two companies where drawn randomly from each sector with two managers being targeted as respondents from each company selected. The sample also included managers from other relevant organizations including the Ministry of Tourism and Hospitality, Zimbabwe Tourism Authority (ZTA), Zimbabwe Investment Authority (ZIA) and Zimbabwe Revenue Authorities (ZIMRA).

Primary data collected was both qualitative (collected through face-to-face and phone interviews) and quantitative (collected through questionnaire survey). A total of 30 interviews were held whilst 50 questionnaires were distributed through email, post or by hand, to the rest of the sample respondents. Data gathered spanned the period 2007 to 2013 inclusive. Simple analysis of secondary and primary data helped in coming up with decisions related to the study. Excel package was used to analyse data, which was presented using simple graphs.

To fully understand the impact of any policy implementation, governments, policy makers and businesses around the world require accurate and reliable data on trends in the sector before and after the implementation. The basic requirement of data is to help assess policies that govern future industry development and to provide knowledge to help guide successful and sustainable investment decisions. The general lack of data on levels of financial investment in Zimbabwe compromised the full conclusion on actual levels of investment in the industry and the extent to which the country benefited. There was also a general tendency by interviewees and questionnaire respondents to respond positively in situations where negative response was eminent. Because of this, published information was preferred due to lack of bias.

Summary of Findings

This section looks at gathered data about Zimbabwe's position in the world economy with regards to the tax incentives instituted in the tourism sector to garner investment in the sector.

i. Findings from questionnaires and interviews

This section looks at responses from questionnaires distributed and interviews conducted. Out of a total of 50 questionnaires distributed 39 were returned, representing a 78% response rate and a total of 30 interviews were conducted representing a 100% response rate.

On issues regarding the general investment levels in the tourism industry, during the period under review, all respondents agreed that there was an increase in the levels of investment. This was in line with the ZTA data, as shown in Table 1 below, for the period 2008 to 2013. According to the table there was a general improvement in the number of newly registered companies from 2008 to 2011, before it started to decline in 2012 to 2013. This might indicate a general attraction into the industry caused by the availability of tax incentives.

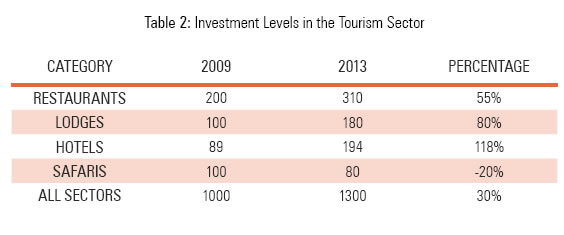

Table 2 below shows a breakdown of investment in various selected categories over the period 2009 to 2013

The table shows a general increase in investment levels during the period under study with the highest investment being in hotels. However, there was a general decline in the levels of investment in safaris. During the same period the tourism sector saw an increase of 8.7% in GDP contribution.

On whether the country had seen an increase in tourist arrivals, 90% of respondents agreed that the country had indeed seen a general increase averaging 2 million per annum generating receipts above US$900 million per annum. The other 10% indicated that there was actually a decline in tourist arrivals, citing the bad publicity the country is suffering from.

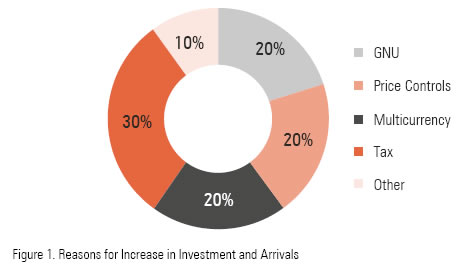

When asked whether the general increase in investment and arrivals was a result of tax incentives introduced in the sector, various responses were given. According to Figure 1 below, increases in tourism investment and arrivals can be attributed to a number or reasons. Up to 20% of the respondents attribute the increases to the establishment of the Government of National Unity (GNU), another 20% to price controls introduced in the sector and yet another 20% to the introduction of the multicurrency system. The introduction of tax incentives is believed to have contributed by 30% of the respondents, especially in investment levels whilst the other 10% constitute the increase to other factors like increased marketing of tourism resorts and a friendly environment in the country. Other respondents actually believe that the negative publicity is helping market the country. Of the respondents who believed that tax incentives did not lead to investment increase, some cited the fact that whilst tax incentives are short term, investments are long term. Thus investors are not motivated to invest in a particular location due to incentives but rather a consistent friendly investment climate.

On the issue of job creation and positive externalities, 100% of respondents agreed that the introduction of tax incentives that led to increase investment in the tourism sector has led to more than a 20% increase in job creation in the sector. Such an increase in job creation has led to increases in the wellbeing of the families concerned and the economy at large.

Other areas covered by respondents especially during interviews include:

Investment climate: Respondents emphasised the importance of the investment climate as a determining factor for the effectiveness of incentives. Zimbabwe lacks a fertile investment climate as seen by contradicting policies. The Indigenisation policy was pointed out by 80% of respondents as the deterring policy for most potential investors in the country.

Negative publicity: Negative publicity was cited as hampering a lot of investors and visitors from coming to the country. As the country ups its marketing strategies some countries will also increase the levels of negative publicity. Risk averse investors are greatly affected in the process as they are seen reviewing their discount rates.

Corruption and red tape: Zimbabwe is ranked as a country with high levels of corruption, which combined with red tape in the process of establishing business in the country, has greatly affected the impact of tax incentives in the tourism sector.

Lack of monitoring: Some respondents bemoaned lack of proper monitoring by the government which led to some investors importing non tourism equipment under the guise of tourism hence fraudulently benefiting from free import duty. Some companies have sold businesses to related parties at the end of a 5-year term in order to prolong the tax free period.

ii. Findings from published reports:

This section covers findings with regard to travel and tourism competitiveness and investment competitiveness. There was a general lack of detailed tourism investment levels from both Zimbabwean and world data. Topics relating environment, human resources, transparency and corruption levels where included in the analysis to help reflect other areas that may have a positive or negative impact on the tax policy. Data was collected from (1) The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index (TTCI), (2) World Investment Reports, (3) Transparency International (TI) and, (4) Zimbabwe Tourism Authority (ZTA) publications.

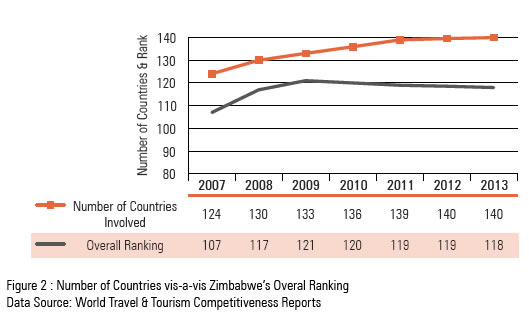

Zimbabwe's General Standing in Travel and Tourism

Over the period 2007 to 2013 Zimbabwe has gradually improved in terms of its standing with regards to attracting tourism sector investors. This is indicated in figure 2 below which shows that whilst the number of countries in the index increased by 13% (from 124 to 140), Zimbabwe's ranking only declined by 10%, indicating, on average, a 3% improvement. The period 2009 to 2013 (the GNU period) saw Zimbabwe moving three places up the rank from 121 to 118 whilst the number of countries in the index increased from 133 to 140, indicating a 7% improvement over the period.

Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Three Pillars

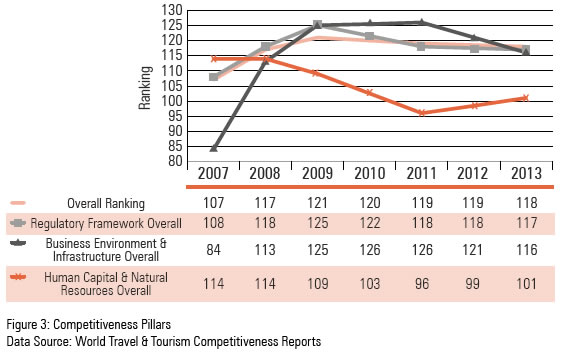

The Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Index is developed around three pillars namely, (1) Regulatory Framework Pillar, (2) Business Environment and Infrastructure Pillar and (3) Human Capital and Natural Resources Pillar. Figure 3 below shows Zimbabwe's trends with regards to the three pillars.

The first pillar captures elements that are policy related and generally under the purview of the government, the second pillar captures elements of the business environment and economic infrastructure, whilst the third pillar captures human and cultural elements of the country's resource endowment. Each of the pillars also has a number of individual variables. According to figure 3, Zimbabwe improved significantly in the area of Human Capital and Natural Resources, having improved from number 114 out of 124 in 2007 to number 101 out of 140 in 2013 indicating an overall 24% improvement in rankings. The greatest improvement was in 2011 when the country was number 96 out of 139 countries. The Regulatory Framework and Business Environment and Infrastructure rankings continued to fall, remaining amongst the worst in the world. The Regulatory Framework fell by 8% whilst Business Environment and Infrastructure ranking fell by 38%. When compared with percentage increase in a number of countries involved from 2007 to 2013, the country's Regulatory Framework actually improved by 5%.

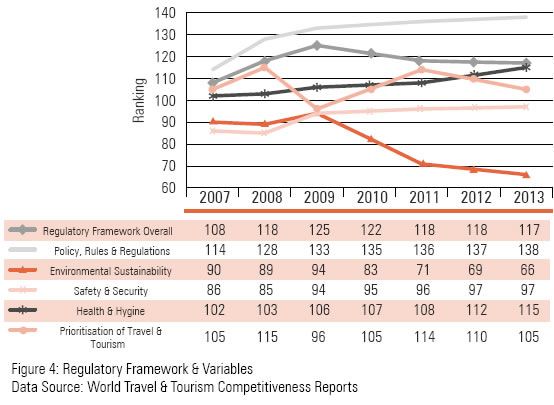

Regulatory Framework Pillar and Variables

Figure 4 illustrates the trend, from 2007 to 2013 for variables falling under the Regulatory Framework pillar.

Figure 4 clearly illustrates that the country's Policy, Rules and Regulation structures remain amongst the dogs, according to Travel and Tourism Policy Risk Matrix. The policy, rules and regulation structure declined by 21% gross (8% net, after taking increase in number of countries into account). During the same period, the country experienced a great improvement in Environmental Sustainability ranking which saw it moving from 90 to 66 in the world. Safety and Security together with Health and Hygiene continued to decline during the period, whilst one of the key variables, Prioritisation of Travel and Tourism ranking remained relatively, but poorly, constant at an average of 107.

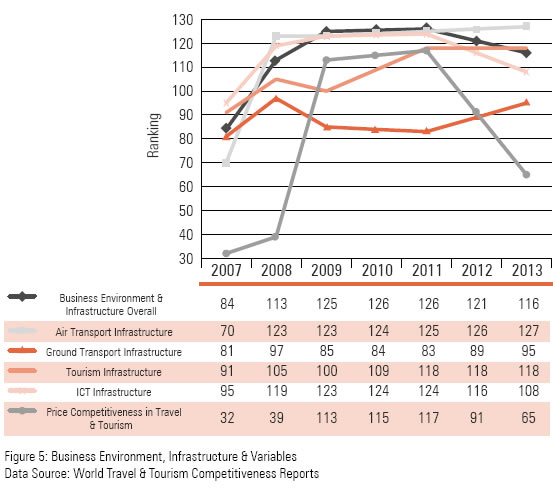

Business Environment & Infrastructure Pillar and Variables

Figure 5 below shows how competitive the country is with regards to Business Environment and Infrastructure. Zimbabwe remains quite competitive with regards to pricing and ground transport infrastructure. Whilst the country remains competitive in pricing, the net fall (90%) over the period was quite huge due to the effects of mispricing in early days of Multicurrency system before a general improvement in 2012 and 2013. The ground transport infrastructure saw a marginal net fall of 4% over the period. One of the key variables for this research, Tourism Infrastructure fell by a net 17% from 91 to 118 in 2007 and 2013 respectively. It is interesting to note that over the period 2009 to 2013 tourism infrastructure ranking fell by 5% net. Thus even after the introduction of incentives the tourism infrastructure continued to fall.

Human Capital & Natural Resources Pillar and Variables

Of interest is the country's affinity for travel and tourism which fell heavily, by a growth of 276% (from 29 to 109 in world ranking) from 2007 to 2009 before improving by 14% over the period 2009 to 2013 after taking an increase in countries in the index into consideration.

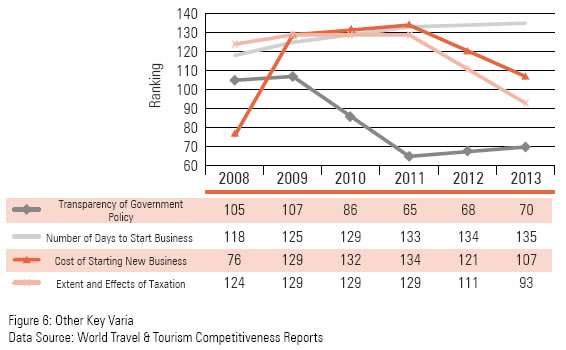

Other Key Variables

Other key variables analysed in this research are Transparency of Government Policy, Number of Days and Cost to Start a Business, Extent and Effects of Taxation and Corruption levels in Zimbabwe. Figure 6 below illustrates the results. The figure shows that it takes too long for one to start a business in Zimbabwe (±90 days according to T&T Index), and the country's ranking in this regard continued to decline over the period reaching number 135 in 2013, a fall of 14% gross and 8% net from 2008 rankings. The costs of starting a business in Zimbabwe also, are relatively high but the country is showing improvements in that regard. The country's ranking increased from 134 in 2011 to 107 in 2013 showing a gross improvement of 20% over the period.

The country's transparency in terms of government policy improved significantly from 2009 to 2013. After falling by 2% during the period 2009/2008, the ranking improved by 40% (net) from 2009 to 2013 with the best ranking of 65 in 2011. Thus whilst the country's policy, rules and regulations remained poor, their transparency greatly improved.

Extent and Effects of Taxation ranking improved by 33%, net, over the period 2009 to 2013. This is one key variable that indicates the impact of tax incentives on tourism industry investors.

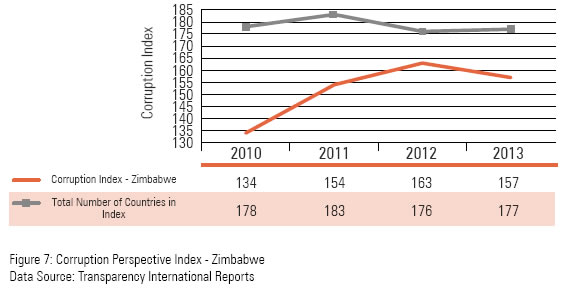

Figure 7 shows Zimbabwe's corruption levels over the period 2010 to 2013 according to Transparency International rating. Transparency International ranks countries based on how corrupt a country's public sector is perceived to be.

According to Figure 7, Zimbabwe remains one of the most corrupt countries in the world making investment in the country quite difficult and costly. The country also remains one the most corrupt countries in Sub-Saharan Africa.

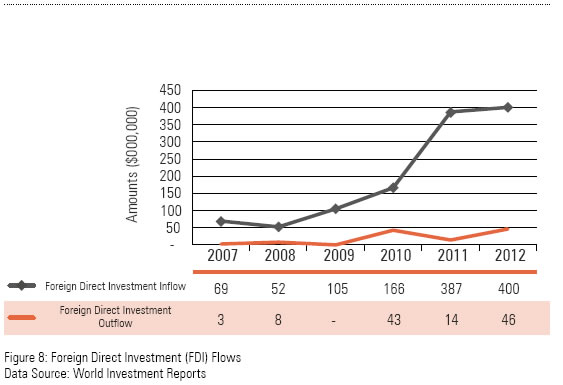

Foreign Direct Investment Flows

As shown in figure 8, Zimbabwe saw a great jump in FDI inflows from 2008 to 2012, 669%, and the trend still shows an upward movement. Some Zimbabwean companies are also finding places in the global economy as shown by a steady increase in FDI outflows from a mere $3 million in 2007 to $46 million in 2012.

The data, however, does not show sector specific investments hence making it difficult to isolate tourism FDIs. According to ZTA (2012), 70% of tourist operators in Zimbabwe are local operators whilst 30% are foreign operators.

Conclusions

This paper reaches the conclusions that:

1. For tax incentives to be effective governments must take a holistic approach to policy formulations. Whilst the Indigenization and Economic Empowerment Act 2007 states that at least fifty-one per centum of the shares of every public company and any other business shall be owned by indigenous Zimbabweans, the Zimbabwe Investment Authority Act (Chpt 14:30) empowers the ZIA Board to plan and implement investment promotion strategies for the purpose of encouraging investment by domestic and foreign investors. One will be left wondering how the later will succeed in luring foreign investment given the former.

It is therefore important that:

- Governments identify specific areas for growth and invest time and effort in formulating policies that ensure that such areas have grown to specific levels within a given period of time.

- Government policies must be transparent, simple and applied equitably amongst current and prospective investors.

- The time and cost of starting a business in the country must be competitive so as to bring confidence amongst investors.

- Information must be readily available to all interested parties to ensure effectiveness in analysing costs and benefits associated with the tax incentive.

- Governments must understand that when applied on their own tax incentives have limited growth impact. The tax authorities should ensure that the benefit awarded through incentives is not lost through other tax obligations or policies. The fall in Zimbabwe's standing in terms of its regulatory framework, business environment and infrastructure framework acted negatively towards its aim of achieving growth in the tourism industry.

- While the provision of tax incentives is considered to be financing from within, the government should aim to provide additional financing, through state owned financial institutions, to the tourism industry to boost investment.

2. Data on new entrants into the tourism industry in Zimbabwe indicate a general improvement in investment in the industry, however the data does not show the number of already existing companies that simply renewed their registration under new ownership. Whilst such a registration is regarded as a new company it does not add value to the industry. Such a company will still enjoy the same benefits as purely new companies enjoy without bringing in new investment into the industry. Such a company will have the opportunity to shift the tax incentives to other industries if audit follow ups are not carried out. Governments must stand ready to lose revenue in all related goods and services imports when proper measures are not put in place for audit trails.

The general lack of data on the cost effectiveness of tax incentives in the sector under study affected the proper evaluation of the extent to which the government and, of course, the country at large benefited. Countries must ensure that proper data is compiled for public analysis to enhance future decision making.

3. Governments need to work towards the minimisation or elimination of corrupt activities in all public sector organs, especially at points of entry and in revenue collecting institutions. Same treatment is required for all goods or services from both politicians and non-politicians. This will eliminate highly orchestrated levels of corruption, which affects the effective implementation of polices countrywide leading also to poor safety and security conditions. According to data, corruption levels in Zimbabwe remained high during the period under review. Such levels of corruption in the country's public sector imply that investors are forced to folk out more than the benefits they anticipated from tax incentives. When corruption costs are taken into account in coming with capital investment decisions, investment costs and the cost of capital will increase causing investment in the country to be expensive and unprofitable.

4. There is a need for governments to effectively promote the tourism sector in and outside the country. This may include:

- Decentralisation of tourist promotion centres to allow all tourist attraction sites to have equal opportunities of promotion.

- All tourism promotion centres, country's embassies and all government travel and tourism agencies and ministry need to have updated websites detailing all areas of tourist investment and visitor attraction centres.

- Open up to more local and foreign travel agents for effective promotion of the country's travel and tourism centres.

- For investment to grow the industry has to be protected from any counteractive laws and policies. It is essential that the government is consistent in the policies they make. Policy reversal lowers the level of confidence that firms have with the government. History tells that it is difficult to make investment decision based on a government policy if the government has a history of policy inconsistence.

- Government interference in the industry must be minimal and any government owned companies in the industry must face same treatment as private companies and must be pace setters in the industry not laggards.

5. Developing countries have the capacity to grow their tourism industries without resorting to tax incentives because:

- Tax incentives will not benefit a company in its early stage because such a company will still be making losses anyway.

- Tax incentives are short term whilst investments are long term, thus the use of tax incentives will not benefit the company in the long run when support is really needed.

- Tax incentives are costly to manage when loopholes exist in the government policies.

- Tax incentives are prone to abuse by authorities in charge of approving or monitoring the applications for such incentives.

- Once the country has its policies in place to attract investors in tourism and other industries and such policies are not applied selectively, with minimal country and political risk then the country will be able to grow its travel and tourism industry without resorting to the costly tax incentives.

- An alternative will be to apply minimal tax rates to all industries as compared to resorting to tax incentives to targeted industries.

Finally, the study did not look at the cost effectiveness of tax incentives, an area that needs further analysis for an overall evaluation of tax incentives' impact on the tourism sector investment and income. Also, the issue of the relationship between tax incentives and excess burden on demand for tourism sector investment needs further exploration.

1 As quoted in http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/in_depth/archive/2003/default.stm

2 As quoted in http://www.amaizingvictoriafalls.com/

3 Harvey was analysing the impact of a housing subsidy and its relationship with consumer surplus on US government.

Reference

Ahmed, Q.M. (1997b), The Influence of Tax Expenditures on Non Residential Investment. Ph. D. Diss, University of Bath, Pakistan. [ Links ]

Bergsman, J. (1999). Advice on Taxation and Tax Incentives for Foreign Direct Investment. Washington, D.C.: World Bank, Foreign Investment Advisory Service. [ Links ]

Boehlje M. & Ehmke C., (1998) Capital Investment Analysis and Project Assessment. Agriculture Innovation and Commercialization Centre, 1-11. Retrieved from: https://www.extension.purdue.edu/extmedia/ec/ec-731.pdf [ Links ]

Boura Panagiota (nd) The Effect of Tax Incentives on Investment - Decisions of Transnational Enterprises (TNEs) in an Integrated World: A Literature Review [ Links ]

Brown, I. (2012). Tourism Industry Backs Tax Stand: http://www.jamaicaobserver.com/business/Tourism-industry-backs-tax-stand_11080916 [ Links ]

Brown, I. (2012). Tourism industry backs tax stand. Jamaica Observer. Retrieved from: http://www.jamaicaobserver.com/business/Tourism-industry-backs-tax-stand_11080916 [ Links ]

Buss, F. (2001). The effect of State Tax Incentives on Economic Growth and Firm Location Decisions. Economic Development Quarterly, 15(1), 90-105. DOI: 10.1177/089124240101500108 [ Links ]

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) World Fact-Book (2012). Retrieved from: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/download/download-2012/ [ Links ]

Clark, P. (1979). Investment in the 1970s: Theory, Performance, and Prediction. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 10(1), 73-124. Retrieved from: http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/projects/bpea/1979-1/1979a_bpea_clark_greenspan_goldfeld_clark.pdf [ Links ]

Clark, S., Cebreiro, A. & Bohmer, A (2007). Tax Incentives for Investment- A Global Perspective, OECD Working paper, USA. [ Links ]

Corthay L. & Loeprick J. (2010). Taxing Tourism in Developing Countries: Principles for improving the investment climate through simple, fair, and transparent taxation. Investment Climate in practice (1), 1-8. Retrieved from: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/10485 [ Links ]

Cummins, J., Hasset, A. and Hubbard, G. (1996). Tax Reforms and Investment: A Cross Country Comparison. Journal of Public Economics, 62(1-2), 237-273. DOI: 10.1016/0047-2727(96)01580-0 [ Links ]

Davidson, H.W. (1980) The Location of Foreign Direct Investment Activity: Economic Growth: The Case of Ghana. Studies in Economics and Finance, 25(2), 112-130. [ Links ]

Fisher, P., & Alan, H. (1998). Industrial Incentives: Competition Among American States and Cities. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17848/9780585308401. [ Links ]

Friedman, J., Gerlowski, D., & Silberman, J. (1992), What Attracts Foreign Multinational Corporations? Evidence from Branch Plant Location in the United States. Journal of Regional Science, 32(4), 403-418. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9787.1992.tb00197.x [ Links ]

Fuest,C.,Huber, B. & Mintz, J. (2005). Capital Mobility and Tax Competition. Foundation and Trends in Microeconomics, 1(1), 1-65. [ Links ]

Goolsbee A. (1997). Investment Tax Incentives, Prices, and the Supply of Capital Goods. NBER Working Papers 6192, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. [ Links ]

Hall, R. & Jorgenson, D. (1967). Tax Policy and Investment Behavior. American Economic Review, 57, 391-414. [ Links ]

Harvey S. & Gayer, T. (2010). Public Finance. 9th Edition, McGraw Hill, Singapore. [ Links ]

Head, K., J. Ries & Swenson, D. (1999). Attracting Foreign Manufacturing: Investment Promotion and Agglomeration. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 29(2), 197-218. DOI: 10.1016/S0166-0462(98)00029-5 [ Links ]

Heritage Foundation (2012). Index of Economic Freedom Data: www.heritage.org/index/pdf/2012/book/index_2012.pdf [ Links ]

Indiginisation and Economic Empowerment Act 2007: http://archive.kubatana.net/html/archive/legisl/080307ieeact.asp?orgcode=par001&year=0&range_start=1 [ Links ]

James S (2009). Incentives and Investments: Evidence and Policy Implications; Multilateral Investment Agency, World Bank. [ Links ]

Jorgenson, D. (1963). Capital Theory and Investment Behaviour. The American Eco Review, 53(2), 245-259. [ Links ]

Klemm, A. (2009). Causes, Behaviours and Risks of Business Tax Incentives, IMF Working Paper, 21, 1-28. [ Links ]

Kransdoff, M. (2010). Tax Incentives and Foreign Direct Investment in South Africa. Journal of Sustainable Development, 3(1), 68-84. Retrieved from: http://www.consiliencejournal.org/index.php/consilience/article/viewFile/107/26 [ Links ]

Machipisa, L. (2001). Sun sets on Zimbabwe tourism. BBC News. Retrieved from: http://www.news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/africa/1220218.stm/ [ Links ]

Malaysia Incentives - Tourism Sector: http://malaysiabusiness.webs.com/tourism.htm [ Links ]

Mauganidze (2010). Zimbabwe announces incentives for tourism investors. Zimbabwe Daily News. Retrieved from: http://www.zimbabwesituation.org/?p=21870 [ Links ]

Mohnen, P. (1999). Tax Incentives: Issues and Evidence. Scientific Series, 32. 1-24. [ Links ]

Morisset, J. & Pirnia, N. (2001). How Tax policy and Incentives affect Foreign Direct Investments: A Review. Occasional Paper 15, FIAS, Washington D.C., USA. [ Links ]

Morriset, J. (2003). Tax Incentives, Public policy for private sector, Vol. 253. [ Links ]

Munyeza Shingi (2009). Reviewing Zimbabwe's Tourism Industry: Opportunities for Private Investors. [ Links ]

Ngowi, H. (2000). Tax Incentives for F.D.I.: Types and who should/ should not qualify in Tanzania, The Tanzanet Journal, 1(1), 100-116. [ Links ]

Nsiku N. & Kiratu S. (2009). Sustainable Development Impacts of Investment Incentives: A Case Study of Malawi's Tourism Sector. International Institute for Sustainable Development. Retrieved from: http://www.iisd.org/tkn/pdf/sd_inv_impacts_malawi.pdf [ Links ]

Panagiota, B. (2009). The effect of Tax incentives and Investment- Decisions of Transnational Enterprises, MIT Press, 3-19. [ Links ] PKF International Tax Committee (2013). Zimbabwe Tax Guide 2013 pp. 541-547. Retrieved from: http://www.pkf.com/media/1956673/worldwide%20pkf%20tax%20guide%202013.pdf [ Links ]

Riley, G. (2008). Capital Investment and Spending, International Economy. Elton College. [ Links ]

Sacks A. (2012). The Outlook for the Global Economy and Caribbean Tourism. Oxford Economics. Retrieved from: https://www.caribbeanhotelandtourism.com/events-chtic/downloads/2013/Presentation_Adam-Sacks-Tourism-Economics.pdf [ Links ]

Smith, F. (2003). Conducting your Pharmacy practice Research project. London: Pharmaceutical Press. [ Links ]

The Indian Express (2009). Selja seeks tax incentives for tourism sector. Retrieved from: http://www.indianexpress.com/news/selja-seeks-tax-incentives-for-tourism-ssector/481699/ [ Links ]

Transparency International (2013). Corruption perceptions index 2013. Retrieved from: https://www.transparency.org/cpi2013/results [ Links ]

United Nations Conference On Trade And Development (UNCTAD) (2000). Tax Incentives and Foreign Direct Investment. Geneva: ASIT Advisory Studies No. 16 A Global Survey. [ Links ]

United Nations World Tourism Organisation (2013). UNWTO Tourism Highlights 2013 Edition. Retrieved from: www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284415427 USAID (2013). [ Links ] USAID Strategic Economic Research and Analysis – Zimbabwe (SERA) Program. Positioning the Zimbabwe Tourism Sector for Growth: Issues And Challenges. Retrieved from: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00J7ZV.pdf [ Links ]

Van Parys, S & James, S. (2010). The Effectiveness of Tax Incentives in Attracting FDI: Evidence from the Tourism Sector in the Caribbean. Universiteit Gent: Working Paper; September 2010. Retrieved from: http://wps-feb.ugent.be/Papers/wp_10_675.pdf [ Links ]

Veugelers, R. (1998). Technological collaboration: an assessment of theoretical and empirical findings. De Economist, 146(3). pp. 419-443. DOI: 10.1023/A:1003243727470 [ Links ]

Wasylenko, M. (1997). Taxation and economic development: the state of the economic literature. New England Economic Review, issue pp. 37-52. Retrieved from: http://surface.syr.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=ecn [ Links ]

Whitman G. (1975). Making the Best Use of Investment Incentives. Managerial Finance, 1(3), pp. 198 - 208. DOI: 10.1108/eb013362 [ Links ]

World Bank Country Data (2013). World Development Indicators 2013. [ Links ]

World Economic Forum (WEF) (2013). Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report (2013). Retrieved from: www.weforum.org/reports/travel-tourism-competitiveness-report-2013 [ Links ]

World Economic Forum (WEF) (2015). World Travel & Tourism Economic Impact Report (2015). Retrieved from: www.weforum.org/reports/travel-tourism-competitiveness-report-2015 [ Links ]

Zee, H., Stotsky, J., Ley, E. (2002). Tax Incentives for Business Investment: A Primer for Policy Makers in Developing Countries. World Development, 30(9), 1497-1516. DOI: 10.1016/S0305-750X(02)00050-5 [ Links ]

Zimbabwe Investment Authority (n.d.). Doing Business in Zimbabwe – Tourism. Retrieved from: http://www.investzim.com/attachments/article/319/Tourism.pdf [ Links ]

Zimbabwe Act (2006). Zimbabwe Investment Authority Act (Chpt 14:30). Retrieved from: http://www.archive.kubatana.net/docs/legisl/ziminvest_auth_act_060908.doc [ Links ]

Zimbabwe Tourism Authority (n.d.). Trends & Statistics Report 2012. Retrieved from: http://www.zimbabwetourism.net/images/Downloads/zimbabwe-tourism-trends-and-statistics/tourism-trends-and-statistics-2013-annual-report.pdf [ Links ]