INTRODUCTION

Any individual or community is naturally embedded in social relations (Granovetter, 1985). It is through these social relations that different types of ties between entities are created (Granovetter, 1973) and these connections can establish a way to relate not just individuals, but can create ties among groups as well, making it possible to manage a two mode relationship (Breiger, 1974). A network is represented by the entities (individuals or collectivities) and their corresponding connections (Granovetter, 1976).

From the standpoint of the Resource Dependence Theory (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978) the resource is strongly indicated as a need of organizations for their survival and to achieve good performance. However, the simple presence of a network is not suftcient to ensure obtaining benefits from it. In order to get access to the benefits of a network, it is necessary to identify what kind of resources are available from it, and most importantly, take notice of strategic and valuable resources that are not available from the organization’s internal sources (Hitt, Ireland, Camp & Sexton, 2001). The group of valuable resources that a firm could obtain from its network is called social capital (Adler & Kwon, 2002; Parkhe, Wasserman & Ralston, 2006) and the organization must make proper use of this social capital according to the surrounding conditions of the business environment (Kwon & Adler, 2014).

According to Breiger (1974), a two-mode network is a structured configuration formed by individuals and communities both at the same time. Some of the main characteristics of this configuration, such as cohesiveness or connectivity, could possibly be framed with specific “Small World” properties (Travers & Milgram, 1969) defined by the length between entities, meaning the distance from one point to another; and clustering level, that implies network transitivity (Conyon & Muldoon, 2006). Firms are collectivities, and they are related to each other through inter-organizational relationships such as their board of directors. A corporate network is created when boards of different companies establish connections between themselves through business relationships where many resources such as information, trust, knowledge or access to capital may be found. Different types of corporate networks were studied before such as ownership networks, equity or interlocking directorates. This study will focus on the literature review about the latter, following the research questions explained below.

IDs occur when a director sits on more than two boards opening the availability of new resources for each firm (Haunschild & Beckman, 1988; Shipilov, Greve & Rowley, 2010) or the possibility of control and coordination between them (Boyd, 1990; Mizruchi, 1996; Palmer, 1983; Salvaj, 2013; Salvaj & Lluch, 2014; Lluch, Salvaj & Barbero, 2014). Furthermore, the formation of an ID may be due to individual interests of the directors (Zajac, 1988) or a wide class influence against the logical business criteria (Useem, 1984).

The relevance of this study is to understand how IDs global research has been evolving, while finding outcome patterns across the firms evolution. This allows us to contribute in answering Mizruchi’s question regarding what interlocks really do in (1996), while clearing new paths for future research that could complement current findings, while reinforcing concepts where the literature is scarce. Understanding how IDs research evolution and its effect on firms’ outcomes contributes to building a consensus on Mizruchi’s question in IDs literature, while finding out if IDs are or are not reinforcing managerial practices are explained.

Making a differentiation between IDs research evolution among certain regions such as in Latin America or other emerging markets’ groups with the rest of the world could prove interesting, as most studies aim to explain the effects and characteristics of IDs under an environment’s stable conditions such as those in The United States or in European countries (Lluch et al, 2014). However, Latin America has a completely different business environment, with weak and ineffective governments, small and ineftcient non-profit organizations as well as many cultural problems for developing strategies (Jäger & Sathe, 2014), which forces organizations to prepare themselves by using different growth and survival initiatives for this complex and turbulent context, and under high levels of uncertainty (Vassolo, De Castro & Gomez-Mejia, 2011).

The focus of this paper proposes a categorization of IDs research according to the firms results in having a regional perspective. Accordingly, the study answers the following two research questions: (1) For the firms studied, what was the main business contribution of IDs global research? (2) What is missing for IDs global research evolution in the years ahead?

This literature review proposes to contribute to the existing body of corporate networks’ research and to maintain an open discussion of the characteristics, benefits and advantages in creating interlocking directorates for firms, as well as identifying how researchers can contribute to the future growth of this organizational field.

This paper is organized as follows: The second section describes the method used for selecting papers, and how the literature was categorized. The third section contains the main document where the literature is detailed according to its contribution to the firms. The fourth part aims to provide a discussion regarding six different metrics that highlight patterns of IDs research evolution. Finally, the fifth section summarizes the principal findings of the literature review, focuses on answering the two research questions previously mentioned and proposes new paths for future research.

METHODOLOGY

The study was conducted with an extensive review of 75 IDs research papers (from 1969 to 2018), in order to identify and analyze their main findings, categorize them by their region of study and their contribution for companies. Out of the total sample, 70 of the papers were empirical and 5 were conceptual with no associated region of study. Table 1 shows the composition of the sample by convenience, as pointed out in the 2017 Scimago Journal and Country Rank for scientific journals.

Table 1 Papers inside the sample according to their Journal Scimago Ranking 2017.

| Journal Scimago Rank 2017 | Papers | % Accumulated | |

| Q1 | 58 | 77% | |

| Q2 | 4 | 83% | |

| Q3 | 3 | 87% | |

| Q4 | 2 | 89% | |

| Non-ranked | 8 | 100% | |

| Total | 75 | ||

Source: Own.

According to Table 1, 83% of the papers in the sample are in journals ranked as Q2 and above. The sample includes 39 different scientific journals and 4 books, and this selection was focused on heterogeneity and prestige criteria. However, there are eight non-ranked papers in the sample that are book chapters, which were selected according to their relevance and novel contribution for their regions. Table 2 aims to show the distribution of the sample according to the decade of publication of the papers inside.

Table 2 Papers inside the sample according to their publication decade.

| Publication decade | Publication decade |

| 1960s | 1 |

| 1970s | 1 |

| 1980s | 9 |

| 1990s | 10 |

| 2000s | 17 |

| 2010s | 37 |

| 2010s | 75 |

Source: Own.

With reference to Table 2, the paper selection for this review includes some research before 1980s, when IDs research was beginning, an important number for the 1980s period and a larger amount of papers for 1990s and later, in order to properly establish trends of IDs research evolution. Specifically, the sample includes 34 different periods between 1969 and 2018.

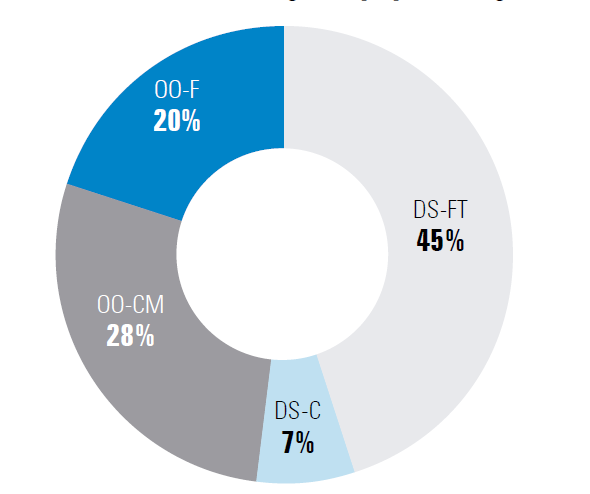

The main IDs literature contributions for firms are organized in this paper under two principal grouping concepts: (1) Description of structures (DS), and (2) Organizational outcomes (OO). Then, the study proposes four subcategories, two for each one of the previous concepts: (1.1) Formation and ties description (DS-FT) and (1.2) Comparative description (DS-C) both for DS concept; (2.1) Control and management outcomes (OO-CM) and (2.2) Financial outcomes (OO-F) both for OO concept. This categorization details the main findings and contributions of IDs papers for firms.

The DS concept refers to a general or detailed description of networks’ structures, characteristics of ties, actors’ role and position within the network, and the evolution of the structure. DS-FT category includes detailed information about the reasons for the formation of the IDS and how corporate ties are constructed, maintained or broken. The DS-C category aims to explore by comparative studies between corporate networks of two or more datasets, finding common patterns and relevant differences, which allow to explain, as well how corporate networks evolve and operate differently in several contexts, economic sectors or groups.

The OO concept is focused on revealing findings in IDs literature closely related to firms’ outcomes. Research has proposed that IDs are created following some specific business targets like acquiring resources or gaining influence and control over a counterpart firm. Therefore, it is expected then that a major trend of IDs research aim to facilitate those objectives for companies. The OO- CM category refers to firms’ outcomes related to the capability to exert control, influence and management over other firms. It means that IDs creation solves monitoring and supervising activities inside the corporate network. On the other hand, OO-F category includes firms’ outcomes related to financial decisions or benefits such as M&A transactions, financial policies diffusion, financial performance, and takeovers decisions.

Finally, the study concludes with a discussion of the results and future trends for IDs global research using six metrics obtained from the dataset of papers reviewed: (1) total of IDs related publications of academic journals by year of release, (2) percentage of IDs related publications per region, (3) total of IDs related publications in North America, Latin America and Europe over time, (4) final year of the studies’ samples for IDs related publications over their years of publication, (5) IDs related publications according to their main findings and year of release, and (6) percentage of IDs related publications according to their contribution.

(1) DESCRIPTION OF STRUCTURES (DS)

There are many different reasons behind the decision to interlock boards. Firms usually like to work together, so they look for cohesive business environments where collective goals would be enforced, trust would be developed, there would be less opportunistic spirit, and a flow of valuable and new information between organizations is facilitated (Lluch et al, 2014). According to such expectations, corporate network structures result as being diverse with regard to their configuration (Davis & Mizruchi, 1999; Mizruchi, Brewster Stearns & Marquis, 2006). The descriptive analysis of the characteristics and patterns found among their connections permit the disclosure of some of those reasons, or other important information about firms’ behavior or their strategies.

(1.1) Formation and Ties Description (DS-FT)

In a review from the period of 1935 through1965, Dooley (1969) identified five reasons for the existence of IDs in a sample analysis of 200 non-financial and 50 financial largest firms in the United States: (1) Size of the organization, the larger the firm, the higher the number of current interlocks, opposite to what Takes and Heemskerk (2016) found later; (2) Management control, referring to the intention of controlling another companies activities by creating IDs with them; (3) Financial interlocks, with two reasons for having them, - fulfilling the necessity of control over an indebted firm or having access to capital to ensure business activity continuity, as Davis and Mizruchi (1999) found in their study of how the role of banks evolved in the United States corporate network from 1982 to 1994, by changing their centrality degree in the structure; (4) Competition, even with the execution of Clayton Act of 1914 in the United States, there was evidence that many companies still had IDs with competitors’ firms in the same market, and (5) Local interest groups, where the most important issue is to keep the unity and integration of a strategic group of firms, relating one to another through shared directors (Dooley, 1969). Therefore, interlocks were created as mechanisms to deal with the uncertainty of the environment, making it possible for the organization to respond accordingly to the demands in context (Pfeffer, 1972).

Directorate interlocks are created to introduce into the firm new valuable resources from the environment; or to support an elite group or some wide class statements in order to maintain the corporate network integration or to follow individual or group’s interests (Richardson, 1987; Phan, Hoon Lee & Chi Lau, 2003). In addition to this, Zajac (1988) found that director’s decisions are driven by personal professional interests, following an individual advancement strategy. After Dooley (1969), a later review by Mizruchi (1996) posed the question: What do interlocks do?, exhibited five main determinants for the creation of interlocking directorates, some of them are focused on the firm’s outputs purposes and others just serve the directors’ interests. The first group considers the following determinants: (1) Collusion, also described by Dooley (1969) as a competition factor, where two or more organizations create these corporate ties in order to obtain an illegal advantage and execute some bad practices in the market; (2) Co-optation and monitoring, again referred to by Dooley (1969) as Management Control, where firms join together through an interlock to share resources and decrease the level of uncertainty that they have to deal with or to gain control and supervision over another organization; and (3) Legitimacy, when the composition of the board, obtained by the formation of interlocking directorates, enhances the reliability of the firm in the business community. On the other hand, the second group of determinants is focused on the construction of corporate ties oriented to: (4) Director’s self-interests as career advancement, stated also by Zajac (1988), when a director is interested in the creation of an interlock just for the purpose to boost his professional career; and (5) Social cohesion, exhibited also by Dooley (1969) as local groups of similar interests and by Useem (1984) as the existence of an Inner Circle, a small group characterized by its power, influence and connectivity over most important political, economic and social actors in a country, where directors aim to maintain the aftliation with a corporate elite (Useem, 1980; Mizruchi, 1996). Regarding risk of collusion through the presence of IDs, Simmons (2011) found no evidence for the establishment of IDs between two competing firms, challenging the previous statements of Dooley (1969) and Mizruchi (1996). However, Simmons’s findings suggested the legality of IDs as time contingent, due to the convergence of the firms’ activities in a specific sector. A later study of David and Westerhuis (2014) stated that the main functions of corporate networks as being four: (1) access to financial capital, usually needed by organizations’ business transactions, (2) channels for information, serving as pipe-lines through which several resources flow (explained later in OO-CM category), (3) control over competition, in accordance with the local antitrust regulations and characteristics and, (4) enhance the reputation of firms, considering the professional background of shared directors and their prestige.

In addition to these findings, Zajac and Westphal (1996) found, over a sample of 491 large firms in the United States during the period 1985-1992, that the reason for creating an interlock obeys mostly to the CEO’s influence and interests, looking to maintain his or her intra-organizational power through the manipulation of inter-organizational interlocks, when the CEO’s decisions of who will be part of the board depends on the level of control that he or she wants to have over the firm. These are similar results to those of Geletkanycz, Boyd and Finkelstein (2001), who demonstrated how CEO external directorate linkages were related to his or her compensation. Similarly, Fracassi and Tate (2012) indicated that powerful CEOs tend to search among directors well connected with them in order to appoint these executives to integrate the board. The result of this manipulation of the board’s composition, through the creation of several IDs, is a weaker monitoring over the CEOs’ business decisions. IDs formation also could be a matter of public policy accomplishment or just to facilitate a specific transaction. According to Cárdenas (2015), the corporate network elite in Latin America is a fragmented one, revealing that countries are mostly interested only in national business transactions rather than management control over the region. They prefer local rather than regional ties, thus stopping the emergence of a transnational corporate network. Silva, Majluf and Paredes (2006) found that Chilean interlocking directorates by 2000 seemed to be there just to ensure an expropriation process or to fulfill some legal requirement. Sometimes these common transactions or obligations can help the creation of IDs. According to Lluch et al (2014), there could be more than one mechanism for network cohesion when an interlocking directorate is created. In their study, at the beginning of the 1970s, Argentina presented a cohesive corporate network considering three major business mechanisms: (1) identity by ethnic condition, (2) family relationships and (3) relationships to a common government agent who was present in many boards, called syndic. Similarly, the presence and number of interlocks can define the boundaries of a business mechanism as well, such as business groups (Khanna & Rivkin, 2006), or family firms (Salvaj, Ferraro & Tapies, 2008).

Regarding the resilience of interlocks, a broken tie occurs when the common director between two firms disappears (Palmer, 1983). As was observed in a research study of over 1,131 firms in the United States during the period 1962-1964, the majority of IDs accidentally broken were not reconstituted again. Furthermore, Palmer, Friedland and Singh (1986) found that just directional ties are more likely to be reconstituted. So according to this analysis, not all broken ties will be renewed; it will depend on the firm’s intentions, requirements and strategic goals (Palmer, 1983). These findings do not support some of the statements made by Dooley (1969) and Mizruchi (1996) who proposed management control and monitoring as reasons for establishing IDs, leading to the expectation of the reconstitution of a broken corporate tie as something natural, something that was not evidenced by the empirical research. Furthermore, those who are or will be the directors’ companions on the board might influence the formation and reconstitution of interlocks. According to Conyon and Muldoon (2006), major interlocked directors tend to sit on boards where there are other highly interlocked ones. A study of the elite corporate network of 100 businesses, 109 nonprofit organizations and 98 government committees in the United States, demonstrated that nonprofit organizations, especially charities and foundations, seem to have a lower integration and central degrees than business and government sectors, where major firms are important actors and have high-profile directors on their boards (Moore, Sobieraj, Allen Whitt, Mayorova & Beaulieu, 2002). Actors who participate inside the corporate network have a responsibility and a correct function, but their final behavior depends on the context and the period where they have to perform. So, the dynamic and flexible roles of these participants mostly depends on the external influences of the environment. In a study of 166 firms in the United States, Mizruchi and Bunting (1981) found that by 1904 the total number of interlocks related to a firm could be improved in order to reveal the firm’s influence according to the strength and direction of the ties. Nevertheless, later, Palmer (1983) demonstrated in his research over the period 1962-1964, that it is not suftcient just to consider their direction in order to find the balance of influence between two interlocked firms. These two contradictory findings reinforce the idea of Mizruchi et al (2006), where the effects of social ties could vary across time. Later analysis had shown that this centrality measure is time contingent, because firms that were highly central in one period, can exhibit a different centrality with the passing of the years, according to the changes of the business environment or the organizations’ strategies (Davis & Mizruchi, 1999), such as what happened with the banks in the United States during the period of 1982-1994, which over time changed their role of high central actors in the corporate network, or the banks and financial institutions in Spain by 2003 (Salvaj & Ferraro, 2005) and in the United Kingdom (Schnyder & Wilson, 2014), demonstrating that corporate networks’ structures evolve alongside countries’ current form of capitalism.

According to Salvaj (2013), Chile maintained its corporate network structure from 1969 to 2005, but the participants within this changed their roles many times. This network kept its cohesion through changes in the regulations of the government, the entry of multinational companies and the capital market development, but its actors played different roles. For instance, at the beginning of the period under analysis, banks were central participants with a high degree of intermediation centrality, but after the economic crisis of 1982 and the open market global phenomenon, banks left this role to local business groups and some multinational firms. Therefore, the Chilean corporate network is a good example of how a group of firms can have a high degree of global centrality, but a weak role as intermediates connectors within this network (Salvaj, 2013). Furthermore, Wilson, Buchnea and Tilba (2017), explained how the role of banks and new financial institutions was enforced over time, from 1904 to 1976, increasing the density of business leaders networks. These cases prove the resilience of the structure for interlocking directorates, but finally, the value of the cohesiveness of a business network comes when firms’ decisions take different paths, some for responsible behavior and others for collusion or other bad practices in the market (Salvaj, 2013). Despite the time contingent volatility of this centrality measure, IDs network seems to have an intrinsic property to maintain the structural characteristics of its configuration. Because of that, any possible removal of the main central boards or highly connected directors from the network will not produce major modifications in its structure, proving its resilience to external changes of the corporate governance factors (Davis, Yoo & Baker, 2003; Naudet & Dubost, 2017). Chilean IDs network had to deal with major political and economic changes in the business environment from 1970 to 2010, but nonetheless, it remained resilient, demonstrating a high level of connectivity between state-owned firms and private business groups (Salvaj & Couyoumdjian, 2015), similar to the Dutch corporate network, which maintained its resilience from 1903 to 2008 and exhibited banks as central actors over that time (Westerhuis, 2014), the same as The United States corporate network between 1962 and 1966 (Mariolis and Jones, 1982), or the Swiss corporate network that demonstrated cohesiveness from 1910 to 2010, banks being in a central position until 1980, when globalization effects reduced the importance of banks within the network and increased the number of outside directors on the boards (Ginalski, David & Mach, 2014; Buchnea, Tilba & Wilson, 2018). Furthermore, Carroll (2002) found that the Canadian corporate network was completely changed from 1976 to 1996 due to external factors in the environment like the trans- nationalization of capital, deregulation of the financial sector and reforms in the corporate governance, all of these reasons associated with the globalization trend. In addition to this, the Argentinian corporate network from 1923 to 2000 drowned in a long-term social deconstruction process that progressively fragmented it, because of the effect of external and internal issues, where businesses were not connected, were unaware of the potential benefits from IDs and finally losing their capability for attracting resources (Salvaj & Lluch, 2014). Resilience of both types of corporate network structures, ownership or interlocking directors, had been tested and proven, as well as other particularities such as traditional ruling class elites. According to Buck (2018), the British ruling class elite endured despite globalization effects over the entire corporate network that represented a huge number of new outside directors on the local boards. Kogut and Walker (2001) emphasized the robustness of the German ownership network structure that allowed it to endure over time, despite the globalization effects on the country’s economic environment. In addition to this, German IDs network had also shown high connectivity and centrality degree in Europe (Cárdenas, 2015), as well as the Spanish IDs and ownership networks (Salvaj & Ferraro, 2005), both representing exceptions to Kogut’s (2012) statement about the unlikelihood that a country has both corporate networks with the “Small-World” properties.

(1.2) Comparative Description (DS-C)

In a study of 1,733 firms in the United States, 2,236 firms in the United Kingdom and 2,354 Germany firms, Conyon and Muldoon (2006) found strong similarities between the corporate network structures of these three countries, according to their “Small-World” properties that were evaluated. To the contrary, Musacchio and Read (2007) did a comparative analysis using 1909 data of Mexico and Brazil corporate networks and found that corporate interlocks are more common in Mexico, where formal institutions are weak or ineftcient and organizations have to support their growth on informal institutions like interlocking directorates, in order to have proper access to important resources for their new ventures or initiatives. On the other hand, the Brazilian corporate network appears to be more fragmented and this structure implies that firms do not have a strong necessity for these corporate ties, because the formal institutions in Brazil were facilitating access to capital and good market conditions for the business community. (Musacchio & Read, 2007).

According to Windolf (2009), antitrust regulation had a fragmentation effect on the United States corporate network, causing its density reduction and weakening of banks. However, Germany’s corporate network density is not only higher than the United States’ is, but also banks had better centrality degree, and bankers a higher position on the boards. IDs enforced the cooperative German business environment but not the competitive one of the United States, thus facilitating German directors to have more social capital than their American counterparts.

According to Salvaj (2013) and Salvaj and Lluch (2014), by the 1960s Argentina and Chile, two countries with a similar type of capitalism, had largely different corporate network structures mainly because of two factors: (1) the country’s political and economic situation and (2) the ownership structures of firms involved in this business network. They found that Argentina’s corporate network structure was fragmented, but on the other hand, the Chilean network had shown a lot of cohesiveness between organizations. It seems that Argentinean firms trust less these board relationships than Chilean ones (Salvaj, 2013; Salvaj & Lluch, 2014). Moreover, Salvaj (2013) and, Salvaj and Lluch (2014) emphasized that a country with weak institutions such as Argentina in that period, did not put its trust on IDs as a substitute action to deal with that weakness. Furthermore, the professional backgrounds of the most-connected directors inside the corporate network are different for both countries. Argentinean well-connected directors tend to be lawyers, government oftcers and accountants, while for Chile these directors are mostly businessmen (Salvaj, 2013; Salvaj & Lluch, 2014). Lluch, Rinaldi, Salvaj and Vasta (2017) also found differences between the evolution of IDs corporate networks of Argentina and Italy, the latter being more cohesive, where banks changed their roles across time and had a strong professional network of syndics. On the other hand, Argentinian banks had shown an irrelevant presence in the corporate network. By the early 1970s, there was a change in the corporate network in Argentina where business groups acted as connectors in this network, establishing business ties with other dispersed firms through the creation of interlocking directorates (Lluch et al, 2014). These business groups’ behavior generated more cohesiveness inside the corporate network in Argentina and set a new role for these firm groups, but one thing remains equal, the most relevant linkers in the Argentinean corporate network during 1970-1972 are still professionals, technicians or syndics, but not businessmen (Lluch et al, 2014). Finally, Windolf and Beyer (1996) also found differences between two European countries, Germany and Britain. IDs in the German corporate network serves mostly to ownership interests, while Britain’s corporate network do not exhibited a particular configuration favoring any group.

Cárdenas (2016) found that by 2012, corporate networks in Latin America exhibited a different structural configuration. Business elites had more cohesion in Mexico and Brazil than in Chile and Peru. Generally, management in Latin America is not related to ownership, and there is less redundancy between ownership and directors networks, considering that this pattern appeared repeatedly some decades ago. The explanation for this might be a globalization phenomenon, which introduced a high number of outside directors on boards, keeping banks in a central position such as in Peru. There is evidence of “Inner Circles” (Useem, 1984) found inside these four countries’ corporate networks.

(2) ORGANIZATIONAL OUTCOMES (OO)

The effects of IDs on a firms’ behavior differ over time, as a consequence of changing markets and professional techniques evolution, how firms adapt their decisions to this evolution and the volatility of the environmental conditions (Mizruchi et al, 2006).

(2.1) Control and Management Outcomes (OO-CM)

The presence of an interlock in the relationship between two firms is enough to know that their behavior will be affected by this corporate tie (Mizruchi, 1996). Some of the consequences of creating IDs are corporate control and network embeddedness. Corporate control ensures having an influence on the decision-making process in other firms or the capacity of monitoring their business activities and obtain critical information from them, considering also that the board’s control role may be segmented through an interlocking manipulation of the CEO, according to his or her personal motivations to attain power (Zajac & Westphal, 1996), obtaining better compensation levels (Geletkanycz et al, 2001) or to have less resistance to his or her business decisions from the board (Fracassi & Tate, 2012). Network-embedded refers to the effect of the firm’s social relations in their strategic business decisions (Granovetter, 1985), using the corporate network as a big scan of the environmental situation and consequently adapting its initiatives to such (Mizruchi, 1996).

Interlocks act as reliable conduits for information and directors’ experiences, facilitating the diffusion and the adoption process of different institutional and managerial practices through the corporate network (Davis, 1991; Davis & Greve, 1997; Shipilov et al, 2010; Shropshire, 2010; Cai, Dhaliwal, Kim & Pan, 2014; Mazzola, Perrone & Kamuriwo, 2016), but the likelihood of this transmission process depends on some specific director’s characteristics and other firm’s conditions, such as their number of interlocks and their position in the network (Shropshire, 2010). Copying practices does not occur blindly, but through a discrimination process according to the firms’ preferences and behavior (Davis & Greve, 1997). Davis (1991) explained how interlock network centrality degree was positively related to the firm’s adoption of poison pill practices, looking for the stability of the business elite members and protecting companies from attempts of hostile takeovers. However, huge firms were unlikely to adopt this managerial practice because their own size represented a suftcient barrier for such transactions. Poison pill managerial practice spreads more rapidly through IDs networks rather than ones of geographical proximity (Davis & Greve, 1997). The presence of director interlocks is related also to the diffusion of quarterly earnings cessation guidance and disclosure policies (Cai et al, 2014) and to the improvement of corporate reporting (Ginesti, Sannino & Drago, 2017). On the other hand, IDs act not just as providers for diffusion of practices, but as constrainers as well, depending on the specific resource they are going to share. According to Ortiz-de-Mandojana, Aragón-Correa, Delgado-Ceballos and Ferrón-Vílchez (2012), financial firms and fossil fuel firms are not likely to adopt environmental strategies because of the effect of director interlocks.

IDs facilitate coordination between firms possibly conducting them to alliances and collusion practices as well (Mizruchi, 1996). An adequate discrimination of how to adopt and use those practices could overwhelm firms’ responsibility when confronting high uncertainty in their contexts or come from communist systems. Following Szalacha (2011), IDs conflict of interests would appear mostly in those environments, where firms tend to operate on the edge of formal/informal and legal/illegal practices, and emerging economies for instance. Regulatory environment, globalization, and general economic conditions can moderate the effects of IDs in such coalitions and make adoption processes. Buch-Hansen (2014), found little evidence of collusion practices in Europe, when these environmental factors are involved.

IDs represent an external source through which several resources flow, enabling monitoring, influencing, co-opting and collaborating activities among firms and their environment. In a study of 80 large firms in the United States in 1969, Pfeffer (1972) determined that a precise presence of interlocks according to the environmental needs was related to firms’ positive performance. The corporate network permits it to monitor and respond to uncertainty of market fluctuations, establishing relationships with banks via interlocking directorates (Burt, 1980). A later research study of board composition and number of interlocks over a sample of 147 companies from different industries in the United States, had shown that firms tend to increase the number of their interlocking directorates and reduce the size of their boards to deal with environmental uncertainty and resources scarcity. Then, these firms concentrated on maintaining directors with a high level of corporate linkages (Boyd, 1990). In addition to this, Bucheli, Salvaj and Kim (2018) maintain that Chilean business groups dealt with the transition period in the economic environment by establishing IDs between them, not abandoning their corporate ties once institutional voids were addressed. To the contrary, a study of 3,745 manufacturing firms in the United States during the period 2001-2009, had demonstrated that IDs do not reduce the uncertainty that a firm has to deal with, but they are capable of enhancing firm performance and bring positive effects to it under the presence of high levels of uncertainty in the business environment (Martin, Gözübüyük & Becerra, 2015). The level of uncertainty has a moderating role in the relationship between the position of these executive ties inside the corporate network and the organization’s performance. So, uncertainty creates the necessary conditions to obtain the benefits of having IDs in the organization, not as a reason for creating them. Similarly, Larcker, So and Wang (2013) previously found that well-connected boards will improve organizational performance especially in firms which are facing adverse situations. These findings are consistent with Beckman, Haunschild and Phillips (2004) research where firms that were facing individually specific uncertainty did not look to expand their corporate network structure, but to increase their interlocks with their current corporate network partners. The need of resources could lead organizations to the establishment of IDs in order to create synergies with other firms with complementary benefits. Bennett (2013), found banks and Chambers strongly connected by interlocked boards over the corporate network, sharing different resources they mutually expected.

Another way to deal with and exert monitoring action over business environment is to seek for influence in the political decision-making process of the organizations. According to Mizruchi and Koenig (1991), the presence of IDs between larger firms within a concentrated industry is related to similar political decisions, where both firms support and make economic contributions to the same candidates. Corporate elite political cohesion is strongly related to the action of IDs in the corporate network, more than members of the same industry or geographical proximity factors (Burris, 2005).

(2.2) Financial outcomes (OO-F)

There are two types of inter-organizational directorship interlocks, one focused on fulfilling its inter-organizational objectives and another one committed to an integration function (Richardson, 1987). Considering this, in the specific relationship between a non-financial firm and a financial one, the non-financial corporation obtained positive effects on its profit performance as a result of the replacement of broken ties in its corporate network, and following its inter-organizational functions as well. The second type of interlocks, according to Richardson (1987), are unrelated to firm profit performance. Furthermore, an analysis of a sample of 191 joint-stock firms in Singapore at the end of 1997 also exhibited these two types of corporate networks, a group of directors who searched for valuable resources and another elite group who sought to maintain their wide class influence in the business community (Useem, 1984), and how these two interlock trends are related to firm performance (Phan et al, 2003). According to this research, those directors who want to attain power and influence through their corporate relationship tend to create interlocking directorates in the intra-industry range, having no effect at all on firm performance and also a negative collusion risk; while boards who are interested in capturing strategic resources for the firm mostly rely on inter-industry interlocks, generating a positive impact on organizational results. This is partially consistent with Larcker et al (2013) findings that well-connected boards have positive results on the firm’s financial performance. Pombo and Gutiérrez (2011) showed similar findings in a study of Latin America of 335 Colombian firms, where the presence of outside directors and the number of interlocks were strongly related to the firms’ financial performance.

Interlocking directorates are also presented as mechanisms related to some specific financial results such as periodical company financial reports. According to Chiu, Hong Teoh and Tian (2013) in their study of 118 firms in the United States during the period 1997-2001, they found that the social contagion effect which flows through a corporate network makes it possible that a non-manipulative firm changes into one because of the presence on its board of a shared director from a manipulative earnings-oriented organization. As opposed to this, a non-manipulative firm that does not have any interlock with a manipulative earnings-oriented one is less likely to acquire this bad practice (Chiu et al, 2013). Mizruchi et al (2006) demonstrated that the effect of corporate ties on the firms’ financial behavior is historically contingent. Firms have shown a less progressive use of IDs in financial decisions as a consequence of the professionalization of financial activity, the internalization of it and the changes in the business environment (Mizruchi et al, 2006). These findings are complementary with Mizruchi and Brewster Stearns (1988) findings that firms tend to seek to have a financial representative on their board when they face solving deficiencies or an increase of their long-term debt, and this decision will allow them to have access to sources of capital, increasing their likelihood of borrowing from financial institutions (Mizruchi & Brewster Stearns, 1994). In addition to this, some factors of the economic environment such as demand for capital or phases of expansion in the business cycle are also positively related to making financial arrangements. Additionally, in response to the conditions of the environment, such as times of economic crisis, financial institutions are likely to demand their presence on non-financial boards in order to be able to monitor their investments (Mizruchi & Brewster Stearns, 1988).

Corporate network of IDs facilitates the diffusion of financial practices or the directors’ experiences, which permit taking financial-related decisions. In the 1981- 1990 period in 327 medium and large firms and their interlocked business community in the United States, Haunschild and Beckman (1988) found that IDs are useful sources of information for a firm’s acquisitions decisions when the focal organization does not have any other substitute source for this financial means. Therefore, according to this, the importance of interlocks as financial information enablers depends on which other sources of information are available for access. Fracassi and Tate (2012) also found firms that had directors with external ties to the CEO that usually decided on more acquisitions, but these decisions finally destroyed the firm’s value. Moreover, Cai and Sevilir (2012) proved that M&A transactions between interlocked firms have different consequences for the acquirer and the target. They found that these M&A transactions between first-degree connected boards, when acquirer and target have a shared director sitting on both boards, tend to favor the acquirer announcing higher obtainable returns, because of the asymmetric information that it has in the face of other bidders and the possibility of bargaining for a lower price, considering also that costs derived from banks or advisors will be less. Quite the opposite occurs in M&A transactions among second-degree connected boards, when both firms have the same director who sits on a third board, and where this kind of connectivity seems to favor the value created by the whole transaction (Cai & Sevilir, 2012). Benefits from financial decisions that come from IDs presence, depend on the type of interlock and the firms’ connectivity level in the network, and finding directors corporate ties as reliable sources of critical information (Zona, Gomez-Mejia & Withers, 2018). Private equity-trade transactions are more likely to occur between firms interlocked by their boards, because directors use their knowledge and past experiences in those transactions to incentive or enhance similar ones (Stuart & Yim, 2010), in the same way that happens with decisions about auditors choice and fees in an interlocked firm (Johansen & Pettersson, 2013), synchronous stock price between Chilean corporate network firms (Khanna & Thomas, 2009) and similar financial policies such as capital investment, R&D, cash reserves and interest coverage ratio (Fracassi, 2016). Finally, corporate elites embedded in social networks allow an imitation process between the participants, reflecting the power of interlocking directorates in the economic and strategic decisions of the largest firms and business groups.

DISCUSSION

The discussion of the literature review results is focused on answering the two initial research questions of this manuscript, the first about the main management contribution for firms of IDs global studies, and the second one about the next steps for IDs research, according to its current progression and its opportunities or limitations beyond this study.

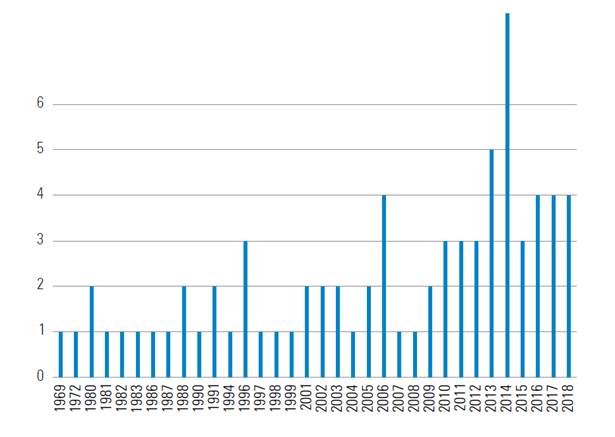

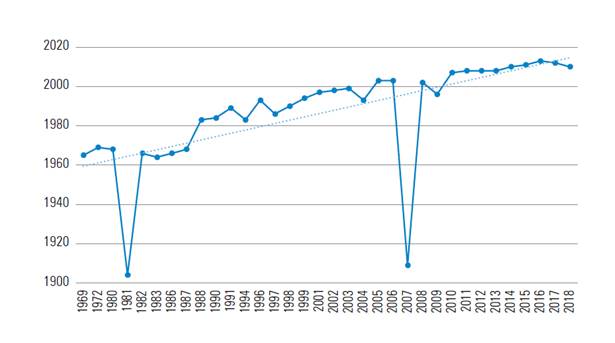

According to Figure 1, there is a concentration of IDs research released since 2006 and ahead, exhibiting a prominent number of papers in 2014. This can be the result of a renewed interest about board management because of the Enron, WorldCom and Tyco economic frauds (2001) and its impact in the global business community, and then Olympus (2011), Barclays (2012) and Petrobras (2014), which keep the attention on companies’ ownership and boards (CNN, 2015).

Own elaboration.

Figure 1 Total of IDs related publications in academic journals by year of release.

Not only corporate scandals increased the interest for IDs research, but new comparative trends and methodologies for research as well. In addition to this, new antitrust legislation and a set of corporate governance regulations in countries boosted the development of this organizational field as well.

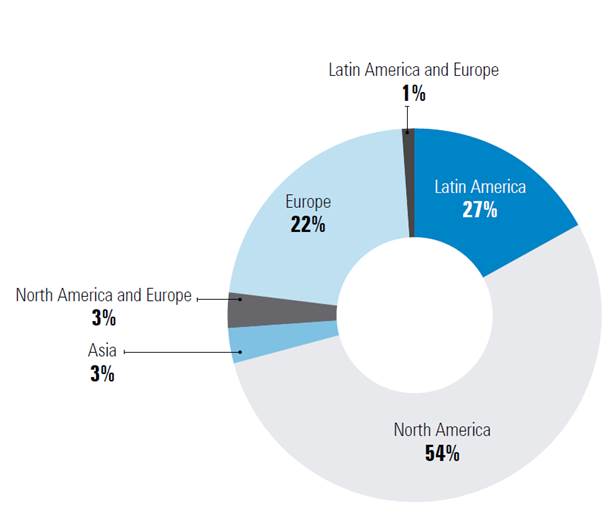

Figure 2 shows the distribution of papers per region of study. The amount of 37 papers was found which focused on the North American region that represents more than 50% of the sample. Europe is in the second place with 15 studies representing 22% of the total sample. Latin America appears with 12 papers, that represents 17% of the total. Finally, the rest of the sample is distributed between Asia and some mixed research between North America and Europe, and Latin America and Europe.

IDs literature requires a balance between regions of study. As there are many papers related to North America IDs corporate networks, it is necessary to explore more related to Europe, Latin America, Asia and the African regions. Since 1914, The United States corporate governance rules changed because of antitrust regulation, which represented a tipping point in the evolution of the business environment for firms. More important, is the finding of a lack of cross-continental research about interlocking directorates. In this review, there are several comparative studies between countries within the same region. However, the manuscript only identified three papers with data from different regions, North America and Europe, and Latin America and Europe. Taking into account that some world-scale events such as globalization, commodities commerce and economic crisis actually have a global impact, it seems strongly relevant to expand IDs literature with these cross continental comparative studies, looking at the effects on corporate networks at different regional levels.

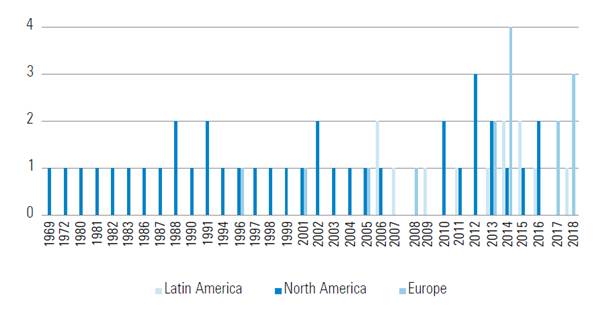

Figure 3 demonstrates the extent IDs literature focused on North America over time and the interest in Europe since 1996, and recently Latin America from 2006.

Figure 3 Total of IDs related publications in North America, Latin America and Europe over time. Own elaboration.

Considering that two conceptual studies of director interlocks in the sample come from 1996 (Mizruchi) and 1980 (Useem), it is interesting how empirical studies are constructed on traditional American perspectives. As a global phenomenon, IDs research has to keep revisiting previous concepts of corporate networks and director interlocks in order to fill in the gaps, due to the progress of management sciences and how empirical studies are opening new paths and questions for future research. Conceptual research of business elites interlocks is urgent in Latin America, considering the huge differences with other regions such as the turbulent business environment of emerging economies (Vassolo et al, 2011) and the variations of capitalism which those countries have crafted (Schneider, 2013).

IDs global research is following an appropriate tendency in the use of data for empirical studies. According to Figure 4, the tendency of the final year in the studies’ samples used in every empirical IDs research is positively related to the year of publication in almost all the cases. In just two cases, the data used was particularly older, as the study observes in the 1981 and 2007 papers.

Figure 4 Final year of the studies’ samples of IDs related publications over their years of publication. Own elaboration.

This finding is encouraging in terms of data availability for IDs research. Scholars have to ensure the recompilation of data and elaboration of data sets that permits proper empirical research for the next years. This also confirms that IDs global research is using data progressively, and capturing its evolution properly.

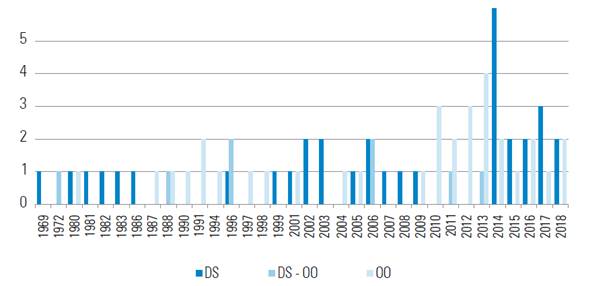

According to the contribution for firms of IDs publications, this study found a moderate concentration of DS related papers since 1960s until 1990s and then, a growing interest in OO related publications. This distribution of papers’ contributions over time can be observed in Figure 5, and this paper argues two reasons to explain it: (1) a better understanding of IDs phenomenon as a first natural step; and (2) the assistance of information technology in the networks field of research, which allow the appearance of more comparative and detailed descriptive papers.

Own elaboration.

Figure 5 IDs related publications according to their main findings and year of release.

It seems that following these findings IDs research has found the balance between these two major trends of description (DS) and outcomes (OO). The equilibrium over quantity and release of publications for each contribution leads one to think that both support each other in order to continue their growth. Descriptive analysis is the basis for an outcome explanation, but it probably does not work in the opposite way. Few cases for DS-OO papers push us to consider that just the contribution papers of the outcomes could be using other sources for basic elements of DS, probably without considering the local context and other important specific characteristics of ties in the corporate network.

Figure 6 displays the IDs publications contribution share over the total of papers analyzed, considering there are eight papers, 10.7% of the sample, with more than one of these four possible contributions, according to the proposed categorization in this study.

The main contribution seems to be a detailed description of structures and how ties operate inside corporate networks, and the second one is related to organizational outcomes, specifically control and management outcomes for firms. So, the current state of IDs research can be summarized as the need of a descriptive analysis of corporate networks structures in order to understand how firms can deal with the uncertainty in the environment, monitoring others and acquiring resources. Nevertheless, it is important to strengthen research focused on the contribution of financial outcomes, because of one of the main reasons of boards’ interlocks existence, the separation of ownership and control, delivering value to stakeholders and solving agency problems as well. Finally, it is important to increase the comparative studies about IDs because the effects of director interlocks are strongly related to changes due to external reasons. Additionally, the comparative analysis of connected corporate elites between countries and regions will permit enhancement of the understanding of the role in context of each corporate network configuration, and the how the role of actors could vary depending on time periods and firms requirements.

CONCLUSIONS

This paper proposes a new two-category structure followed by a four sub-category level for the organization of IDs literature of a sample of papers from 1969 to 2018, according to its main findings as a contribution for the application of practices in firms. In addition to this, the study also proposes six different metrics to discuss the results while answering the two research questions provided in the first part.

IDs literature’s most important contribution for firms is related to the description of the corporate network structures, analyzing the reasons for the creation of these interlocks and describing business elites ties characteristics and particularities. Having a proper description of the nature of director ties’, firms could be able to understand how their connections with other firms are affecting their decision-making processes and, how the constraints and opportunities in the business environment are related to their level of connectivity inside the corporate community. This finding suggests that the biggest IDs research contribution for firms has remained at a descriptive and theoretical level, perhaps unreachable in the practitioners’ field unless appropriate literature channels for management application could be properly driven.

Additionally, it seems that current IDs research is closely related to organizational behavior but focused on control and management outcomes, rather than financial ones. IDs research tends to benefit organizational outcomes when these corporate relationships follow the Resource Dependence Theory statements or the growth objectives of inter and intra-industry business communities. On the contrary, when these director ties aim to preserve the status of an elite group or are oriented to fulfill integration and cohesion goals, they do not have any effect on organization performance. Ironically, one of the main reasons for collaborative and cooperative action through director interlocks is the improvement of capabilities of resources attraction, which would benefit financial performance. However, the results of this study suggest that IDs research have been focused on explaining the structures first and many other additional facts found for financial outcomes.

IDs research exhibited multiple regional gaps, mainly because this organizational field matured first in North America and later in Latin America and Europe. In fact, director interlocks originally came from the type of competitive capitalism which reigns over the United States. However, every region has its own business particularities, regulations and laws trying to shape the way IDs corporate networks grow. Latin America, for instance, has its own opportunities and risks of managing the distance between control and ownership inside organizations, because of the high presence of family firms, informal markets and institutional voids. So, each country and region have similarities and differences, making the reinforcement of IDs comparative studies more important. IDs research focused on Latin America has had a major presence since the 2000s, oriented mostly to comparative and structural studies, and Europe has shown a conservative role using data for this research trend. The Latin America region was a latest adopter of capitalism as an economic system, and its capitalism is different from other regions, limiting its capacity for innovation, making added value products, and growth (Schneider, 2013). The incipient participation of the Latin American region in IDs global research dialogue shows a growing interest of scholars from that region focused on the structure, characteristics and evolution of their corporate elite networks. Further, it urges more cross continental research that would strengthen the organizational field, capture the global effects of major scale events such as financial crisis and globalization, and finally, find evidence about how IDs are actually related to their business environments.

The revisiting of main concepts of Interlocking Directorates Theory seems necessary to have robust evidence about how IDs have been evolving over time, according to their extended application in management sciences. Key conceptual papers come from a North America business environment considering a competitive capitalism that is different from cooperative capitalism in Europe and hierarchical capitalism in Latin America (Schneider, 2013), and specific antitrust regulations which are poorly developed or absent in other regions. In addition to this, data sets used for IDs research are evolving progressively according to the years of publication of the studies. This is an encouraging finding, which provide useful information about the evolution of IDs research and permits the proposal for new paths for future research.

Some of the limitations for the present study may actually present new avenues for future development of IDs global research. This manuscript considers 75 papers as an initial revisit of this controversial and unanswered question about what interlocks really do, building on Mizruchi’s (1996) unfinished debate. It seems necessary then to extend the number of papers in order to reinforce the global view of this phenomenon and to identify new gaps in the literature. Following the theory, IDs represent reliable conduits for the transmission of practices. However, this study misses a categorization regarding the properties and description of diffusion processes in order to separate the positive practices from negative ones. Therefore, it would be interesting in the future to research how specific patterns of the diffusion process involves the presence of IDs, and what their impact on firms’ outcomes is. Big historical or economic events are not considered under the perspective of this study, but previous research has demonstrated the importance of established IDs corporate network configuration into a timeline of big scale events. Globalization for example, is changing the way IDs are connected to firms’ behavior and performance. It will be relevant for future research on globalization to focus on the effects of the evolving configuration of elites networks. Moreover, the latest research contradicts traditional statements such as those related to collusion practice as a consequence of IDs presence in the corporate network, so further empirical research is needed related to collusive activities through director interlocks. This will permit management science to declare those as a potential IDs risk or just as a timely contingent pattern.

Finally, IDs global research is relevant in understanding firms’ decisions, behavior and performance; but director interlocks creation depends on external influences in the business environment, internal forces of individual interests, and the objectives of a hidden business agenda of an elite class trying to enforce its cohesion. Because of these factors, IDs research has to be developed as a globally affected, locally contextual and timely contingent effort.