INTRODUCTION

Mediaindustry, likeothercreativeindustries, stronglydependsoncreativity(Malmelin and Virta, 2016; Dwyer, 2016; Mills, 2016; Virta and Lowe, 2017). creative content is the cornerstone of success of media firms, and in a hypercompetitive industry, the role of creative content becomes more determining (Dekoulou and Trivellas, 2017). Advances is communication technologies and technology convergence has made the media industry hypercompetitive and some new players entered to the field. “In 2013, annual revenue of major media companies (with their parent conglomerates) were just 77.5% of what technological companies such as Netflix, Facebook, Apple, Google and Amazon have earned in the media market (249.69 Billion USD vs. 322.1 Billion USD).” (Cunningham et al., 2015:141). In such a though competitive industry, that media organizations need to compete with technological firms, use generated content are also another serious challenge. Technology made the equipment inexpensive so that individuals with a laptop and portfolio of software can act like a small studio of media content production and Social media enabled the users to share their products easily and widely (Khajeheian et al, 2018). In such competitive environment, media companies in general and public service broadcasts in particular have a diftcult time to survive and to accomplish their missions.

Van den Bulck et al (2018:11-12) point on three fundamentally important challenges of public service media in the age of networked society and new media:

1) the mentality of mass media that is rooted in the broadcasting heritage, 2) the focus on domestic media services and lack of globalization, 3) the strong and increasingly influential push back from commercial media. McElroy and Noonan (2018) studied the digital innovation in public service media in the country of wales.

They introduced four myths regarding public service media and networked society: Myth 1: digital distribution leads to end of linear television; Myth 2: public service broadcasts are redundant; Myth 3: power and control have shifted to audiences; and Myth 4: digital media offer universal access to all. (2018: 162-164). Nissen (2016), who was Director General of the Danish Broadcasting Corporation (DR) from 1994 to 2004, reflected the challenges of public service media managers to stay independent and accountable in the middle of civil society and state.

Also PSBs are expected to deal with the market failure (Steemers, 2017). Public service media are expected to deliver the content that commercial media normally decline to produce due to the insuftcient demand (Vogel, 2018). Cunningham et al (2015) argue that government’s support of Public Service Broadcasts such as BBC in UK, CBC in Canada, NHK in Japan, ABC in Australia and similar cases worldwide, is justified by the nature of public goods that they deliver. However, raise on internet and social media increased the access of ethnics to the contents they want, and some argue that the mission of public service media to provide different groups of society with the diverse content is now fulfilled with the internet. Cunningham et al (2015) show that commercial media and public service media are getting closer to their functions under the new environment of television ecosystem. In such situation, as Jauert and Lowe (2005) argue, the key question in the research on public service broadcasting is the degree of relevance of publicly supported broadcasters in the age of commercialization, convergence and globalization. Undeniably, the idea of participation and the democratic potential of public broadcasters providing ordinary citizens with a voice in the public space has always been a key element of PSB theory and practice (Thorsen, 2013). Several studies showed other functions of PSBs in serving the public interest, such as developing media entrepreneurship. For example, Khajeheian (2014) shows that national innovation systems impact on media entrepreneurship. He also emphasized on the importance of policy making in fostering of innovation and entrepreneurial activities in media industry (Khajeheian, 2016a). Public service broadcasts serve and support social norms (Frank et al, 2012), that positively effect on entrepreneurial actions (Emami and Khajeheian, 2019).

In Iranian context, Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) acts as the exclusive national broadcast. According to Principle 7 of Article 75 of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the national media of Iran belong to the entire nation and must reflect the life and circumstances of all the different ethnic groups of the country. In the 2025 vision of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the national medium (Resaneh Melli in Persian) refers to the IRIB organization that is obligated to save the public interest and must serve the public goals and values of the nation (Alavivafa, 2017).

Until last two decades, the major portion of content production in IRIB had been in-house. Huge investment in physical and human resources and vertical integration from production of news on the scene to terrestrial distribution of frequencies and signals, enabled this large organization to manage all production processes inside. Access to funds and small number of media alternatives, that were limited as published media, made this large organization a favorable destination for creatives and it was easy to acquire innovative ideas by calls and also by hiring innovative people to create content. At the other side, limited alternatives for entertainment and information, make no choice for audiences unless watching IRIB programs.

However, in last two decades and due to severe competition from satellite television channels as well as internet and then mobile-based social media, audiences found more alternatives and choices to consume creative contents. for this reason, the organization acknowledges the need to cooperate with external sources of creativity to present novel and innovative content. From that time, the new structure for catch of external innovation implemented and outsourcing of production became as a routine. However, quick and diverse provision of content in social media encouraged creative talents to operate in social media (Burgess et al, 2006; Sigala and Chalkiti, 2015; Khajeheian, 2016b; Labafi and Williams, 2018) instead of being involved with static stricter and slow decision making processes of IRIB. As internal sources of creativity are limited (Khajeheian and Tadayoni, 2016; Khajeheian and Friedrichsen, 2017), the organization is in a severe need to acquisition of creative talents and innovative ideas. For this reason, the research problem of this paper is that “how IRIB can use external sources to feed creativity to serve the public audience?”

LITERATURE

The area of corporate media entrepreneurship has been studied rarely. Hang (2016) authored the only book in this subject and provided some cases about how a media organization can entrepreneurially manage the resources to create value. In 2019, the new launch Journal of Media Management and Entrepreneurship (JMME) contributed in developing this concept by three research articles: Tokbaeva (2019) studied the Russian media entrepreneurs and how they used the opportunities in an emerging market under digital media presence. Sreekala Girijia (2019) showed how digital news media enterprises in India employ commercialization and commodification as a business model to survive in the market. Finally, Horst and Murschetz (2019) discuss how strategic media entrepreneurship help media organizations to explore and exploit opportunities, to manage human resources, to build networks and to drive creativity.

At the other hand, the topic of creativity in IRIB has been studied in many researches. Roshandel Arbatani et al (2013) studied the challenges of creativity in this organization and proposed a model of human resource development. Karimi and Salavatian (2018) proposed use of gamification to get benefit of audience creativity as a competitive advantage for IRIB. Darvish and Nikbakhsh (2010) studied the relationship between social capital factors and knowledge sharing in research department of IRIB. Ghasemi (2013) studied the challenges and motivations of women in this organization. Ansari et al (2015) identified and ranked the factors that impact on creativity in advertising in IRIB’s commercials. Darvish (2011) showed that entrepreneurial orientation impacts on employee empowerment in IRIB. Motaharrad et al (2014) examined the effect of in-service entrepreneurship training on the level of entrepreneurial activities of IRIB managers. Tahami and Nasirian (2016) proposed a model for human resources strategic management in IRIB and showed that human resource strategic management has a positive effect on innovation capacity as well as performance in this organization.

RESEARCH MODEL

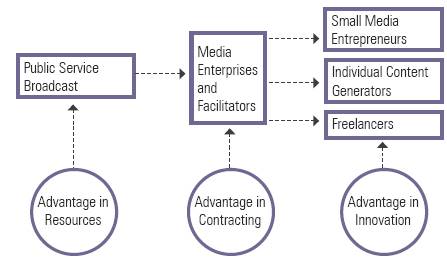

The theoretical model of this research has been taken from Khajeheian and Tadayoni (2016) study of Danish PSB (DR) and how this organization can benefit from user innovation as an external source of creativity. Their model, that is in turn based on Eliasson and Eliasson (2005), suggests that PSBs enjoy from advantage of resources; users and small media entrepreneurs have advantage of innovation; and medium- size media enterprises that benefit from their advantage in contracting, facilitate and connect these two. Therefore, the strategic competency theory is developed as the model of Khajeheian and Tadayoni theory of efficient media market.

Current research is based on this theory of efficient media market and seeks to understand how IRIB can access to sources of innovation and creativity that are existed inside the Iranian public audiences, and in this regard how much Iranian media market is rich with media enterprises as intermediators and facilitators to connect IRIB to these sources.

METHOD

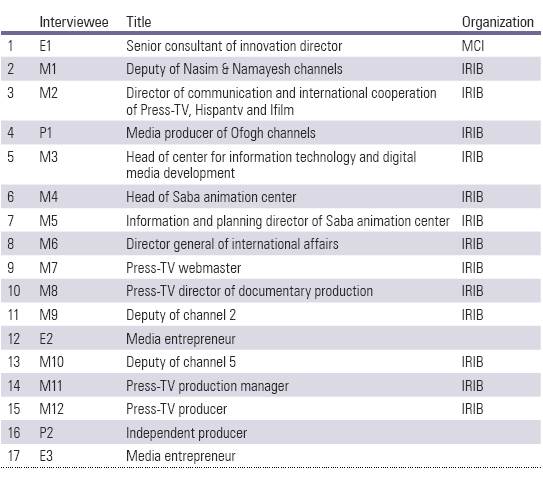

This research is explanatory in nature; and therefore a qualitative approach has been selected. The sample of study consists of a number of top-ranked to middle-ranked managers of IRIB who accepted to participate in the interviews. They are selected by purposeful sampling, that helps the researchers to target the people who are rich sources of information. The means of data collection is in-depth interview, so that the researcher as interviewer defined the problem and asked some open questions about the process of innovation management. then based on the answers and expertise of interviewee, new questions generated and asked. Interviews recorded and then transcribed. To interpret and analyze the collected data from these interviews, theme analysis used as the method. Transcriptions coded in three levels of open, axial and selective codes, and then researchers extracted patterns of data to understand and analyze the way IRIB access to external sources of innovation.

The sample include the interviewees that is listed in Table 1.

FINDINGS

Analysis of interviews produced 60 codes. Researchers classified these codes into five major categories namely, external innovation, corporate entrepreneurship, facilitators, externally-sourced ideas, and co-creation. Interviews show that IRIB outsources a large portion of its content to external producers. For example, Channel 3 outsources about 80% of its programs and Channel Nasim, one of the most successful channels, almost outsources all its programs. Also two of most popular programs, namely Khanevadeh and Dorehami, are produced outside of the organization and the ideas behind them are also raised externally. The sample consensed on the need to actively interact with audiences to understand their ideas and even more, to allow them to participate in the production process of programs.

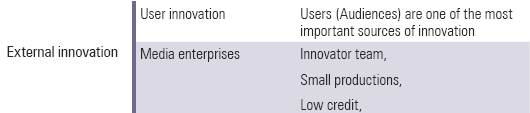

Category 1: External innovation

As Table 2 shows, the involving factors in this category include two classes of user innovation and media enterprises.

i. User innovation

While creative ideas are the cornerstone for success of media companies in a hypercompetitive market, finding good ideas is becoming harder and harder. In such condition, external sources of ideas are a bless and audiences are such a source of creativity:

{10M5} The capital of each media organization is the audience; of course, an active audience that can provide ideas to the media.

IRIB acknowledges these ideas and have started to welcome the external ideas and to convert them to some real products:

{1M6} The channel Nasim treats all ideas and creations openly. The network is not limited to the internally generated ideas.

And:

{1M29} The most popular TV programs have taken their ideas from the creative sources that are out of the organization.

And:

{4M21}We are not a creativity crew. Our task is to be able to accomplish our mission in a limited time. For example: Kannon-e-Parvaresh-Fekri (the Children’s and Adolescent Center for the Advancement of Innovations)

Also IRIB has a well-tied relationship with some external creative organizations, such as Kannon-e-Parvaresh-Fekri (the Children’s and Adolescent Center for the Advancement of Innovations), or Ammar Film Festival as a source of external creativity for students and children.

{1p6} Popular productions such as the documentaries of the Ammar Film Festival have been able to fit into TV antennas in recent years on various topics.

And:

{3M27} PSB can be converted into a creative and postmodern media, if it uses external creative elements.

And

{7M30} Interactive TVs (IPTV) have pushed the PSB to move toward the PSM, which is the way to use external creativity.

ii. Media enterprises

Media enterprises, that are usually small firms that founded by creative teams, are identified as another source of creativity:

{1E7} These enterprises are able to turn their small ideas into a professional product.

And:

{2E11} We have such productions as teaser, short films and short films that have an idea from enterprises’ teams.

And:

{1E25} As we (as media enterprise) have not the sufficient resources to produce the content from our idea, we rely on the credibility and resources of large media companies or government authorities such as the Ministry of Culture.

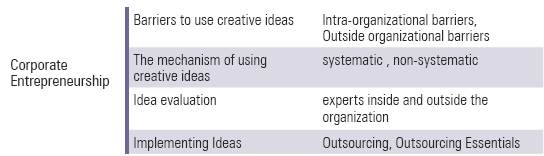

Category 2: Corporate Entrepreneurship

iii. Barriers of using creative ideas

The Barriers to the absorption and use of creative resources outside the organization are divided into two broad categories: Intra-organizational barriers and Outside organizational barriers. Intra-organizational barriers, including organizational bureaucracy, mechanical and very large organization, organization aging, Lack of managerial risk appetite, organizational, missions, lack of organizational culture to attract new ideas, financial constraints and time. The most important barrier is the lack of a regular mechanism for attracting ideas. Outside organizational barriers include the lack of culture of ideas in society and the missions of the sovereignty.

{1M1} IRIB is a large and static organization.

And:

{7M39} The average age of top managers is high, which is one factor for not using creativity. Successful media worlds like Google have an average age of managers and their employees under the age of 30.

And

{13M10} The financial problems of the organization have caused us to not pay enough for the outside ideas of the organization.

And:

{8M1} In the context of our news, we cannot trust the audience completely, they may not know the news or make false information and, as a result, reduce the credibility of the IRIB.

And:

{2M1} The organization is linked to the senior elements of the government, like the three forces of the system. Representatives are also involved in decision-making processes.

iv. The mechanism of using creative ideas

The mechanism for using creative ideas is twofold: systematic and non- systematic. In addition, each network has channels in the cyberspace and website that communicates with its users.

{4M20} The entrance to the plan section is open, via email, Intermediaries and websites, users can give us ideas.

And:

{10M30} Our communication with outside the organization is of two types: systematic and non-systematic. In a systematic way, ourselves, based on scientific methods, study a sample of society. We make targeted sampling that reflects the desire and need of the audience. In non-systematic, public relations, the organization always receives audience opinions

v. Idea evaluation

The evaluation of ideas is done through the experts inside and outside the organization. Experts are those who are aware of the missions and rules governing the organization. They know the principles and rules of programming. They are aware of the priorities, capabilities, infrastructural and technical capacities of the media.

{8M7} We put forward ideas in the unit layout and network plan. Decisions about using ideas in the design unit occur.

And:

{4M9} We announce our production priorities in the beginning of the year. The relevant experts who are professional and who know the rules and priorities of the organization, comment on ideas.

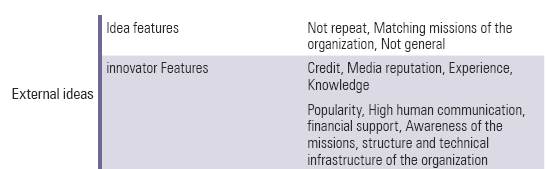

vi. Implementing Ideas

Implementation of ideas in most cases occurs through outsourcing. In outsourcing, acceptable ideas are given to companies or individuals to come to the production stage. These people must have the characteristics, including the reputation, popularity, experience, technical skills, knowledge, financial capital, strong human links with individuals and institutions. Companies should also have the characteristics; familiar with the missions and rules of the organization, sufficient financial credit, have the necessary technical infrastructure, reliable and efficient human resources Advantages of using creative ideas. If the user or the creative company has sufficient conditions, they can execute their plan.

On the whole, in few cases, the organization pays out the costs of producing creative resource ideas outside the organization unless it is able to cover one of the important missions of the organization:

{5M2} All our products are outsourced at Saba Center. Products are deposited with suppliers or private companies.

And:

{1M22} If the idea has a sponsor, we will be prioritized in our evaluation.

And:

{1P5}TV shows include news, documentaries, movies, inter-program and serials, with the exception of news in other cases, the possibility of outsourcing is high. Most outsourcing is in the midst of the program.

And:

{4M9} At the first step, we identify professionals. They should have the necessary equipment and expert staff.

And:

{12M8} When the innovator and producer of the program are the same. It has been cost effective for the organization. We do not have the money to produce. They produce and we play.

Category 3: Facilitators

Khajeheian (2013) expands the theory of strategic acquisition. He proposes that an efficient market provides the possibility of a match between large companies and small ones by facilitators. Though enterprises have an advantage in innovation and large companies have competencies in operation and access to resources, facilitators converge these advantages and create new opportunities by bridging the small and large companies. In this theory, innovations come from small enterprises (including individuals and users) and develop to professional products by large companies.

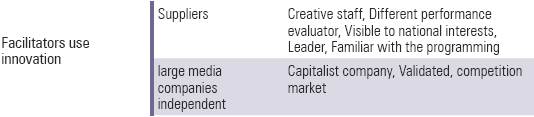

The findings of this study showed two categories of facilitators: Suppliers and large media companies independent of the IRIB.

Suppliers are employees who, even if they are employees of the organization, are not evaluated like other employees of the organization. They are judged by their outcome and also do not have to spend their time in the organization as a creative workforce. They can freely communicate outside the organization with foreign creative resources and use the resources of these resources:

{1E8} The suppliers are a bridge between us and the IRIB.

And:

{7M16} If we can connect creative sources outside the organization to suppliers, we can expect that these innovations will quickly become a product.

And:

{7M18} The Supplier is the person who offers the project to the network, attracts it to the sponsor and receives it. Due to its connections in the network it can approve its design.

Subsequently, large media corporations are massive financial backers, like the Owj media organization:

{2E8} We sell our ideas and our media products to institutions or organizations that have access to IRIB.

Category 4: Externally Sourced-Ideas

The findings of this research show that the factors that make ideas outside the organization accept and produce both depends on the idea and on the one who gives the idea.

{1M21} The ideas that are initiated are the chances of their being implemented.

And:

{1P12} Individuals can give ideas and produce, but they must have a background, especially if the organization wants to allocate a budget for their ideas and work.

And:

{3M40} To be successful media must use a competitive environment, but currently the PSB is known only to the Celebrities and directors.

And:

{7M12} Imagine if a student enters the organization and says that I have this idea, it’s hard to get his idea to the focal point.

Category 5: Co-Creation

Through co-creation, one can create a deep relationship with the audience

{1M25} Our network has a consistent relationship with successful private media companies out of the organization.

And:

{1P11} IRIB sponsors some of the ideas and in some cases allows production outside of the organization to be distributed from the television antenna.

And:

{3M9} Creative users are basically not big capital And they connect themselves to where they have capital and facilities. Media providers provide infrastructure and media makers create ideas. IRIB supports media makers in the virtual domain.

And:

{4M21} We are a government employer and we are sponsoring intellectual supporters. At each stage, we have a representative who will help it with the foreign producer.

And:

{10M16} We produce ten percent of the 90 program in the organization, and

DISCUSSION

This exploratory research aimed to understand how a large media organization like IRIB uses the external resources to present value to its target audiences. The findings of this research confirm the results of a similar study that Khajeheian and Tadayoni conducted in Danish Pubic Service Broadcast (DR). in both cases, the organizations emphasize on professionalism of content and for this reason they rely on the internal production abilities. on the other hand, the major difference is that in the Danish Market there are some intermediaries such as nordiskfilm and metronome that facilitate use of external innovations. In contrast, Iranian market lacks such facilitators and IRIB needs to communicate directly with users and enterprises. This difference supports the idea of eftcient media market, that implies existence of intermediaries with advantage in contracting helps the large and small organizations to get benefit of each other with lower transaction cost.

The findings also confirm the study of Khajeheian and Ebrahimi (2020) that showed social media of newsmedia can encourage audiences to participate in co-creation of value. It can be concluded that digital platforms such as Enterprise social media (Khajehean, 2018; Leonardi et al, 2013) are the tools that can be used for co-creation of value by stakeholders. the co-creation as an activity that can be perform not only between the organization and audiences, but also among the audiences, media enterprises and the organization.

Thus, the main contribution of this research is to confirm the theory of eftcient media market, and to show that there are differences in the national environments that PSBs operate in. when a Public Service Broadcast operate in an eftcient media market, it has the chance of access to the external innovations more easily. In contrast, operating in an ineftcient media market, limits the access of PSB to external sources of creativity that are existed in the society. The results of this study emphasize on the need of media policy making to foster the creation and growth of intermediaries and to develop facilitators to make their operating media market more efficient.

LIMITATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The findings of this research suggest the IRIB managers and policy makers to encourage some middle-level firms to conduct the role of facilitators. Such firms will connect with users and small media enterprises; identify and evaluate their innovations; and introduce the best ones to the large media organization for production. These firms can primarily be established as spin-offs and with support of IRIB, or can be picked from the existing small media enterprises with a social capital to growth as an intermediary.

This research is mainly limited to the sample and tools. The sample is limited because of the diftculty of access to top ranked managers for such a research. 17 managers are fewer than the required number to generalize the results of this study and it is recommended that in the next studies, researchers cover a larger sample. Another limitation is the means of data collection. interview has some limitations to extract the knowledge of interviewee and it is very depended on the skills of the interviewer. For this reason, the authors suggest the future researchers to use a combination of means to collect the data from a more diverse sample of respondents.

The followings are some suggestions for future researches to advance the subject of this study and contribute to the field:

To study the proper structure for public service media to act entrepreneurially to use its resources for delivering value;

To study the eftcient process of identification of sources of creativity and exploiting them by PSBs;

To research how the policy making can develop eftcient media market; to study the incentives and motivations of media firm to undertake the role of intermediaries to connect the external innovation and PSBs.