INTRODUCTION

This review aims to achieve a greater understanding of strategizing, its categories, empirical contexts, as well as, its epistemological, methodological and theoretical matters. This review contributes to foster research on Strategizing or S-as-P, since it has been paid modest attention in Latin America, except for Brazil. Strategizing was born as an alternative approach to mainstream strategy research. Accordingly, Strategizing is understood as an invitation to include human action in the construction and enactment of strategy (Jarzabkowski, Balogun, & Seidl, 2007; Walter & Mussi, 2011). It includes the interaction of people (Johnson, Langley, Melin & Whittington, 2007), socio-cultural artefacts that build strategy (Fenton & Langley, 2011) and the micro-macro ontologies on practice (Seidl & Whittington, 2014).

In an effort to enlarge the scope of Strategy-as-practice as a research field, previous literature reviews have looked for, the “doing” or enactment of strategy: “who does it, what those people do, how they do it, what kind of things they use and the impact of those issues for shaping strategy” (Jarzabkowski & Spee, 2009, p.69). Other authors have provided important insights into the practices, praxis and practitioners’ categories of strategizing (Vaara & Whittington, 2012). However, these works are quite dated given the speed with which the SAP field has been growing over the last few years (Seidl, 2019).

In order to update these literature reviews and to provide a deeper understanding of strategizing for the Latin-American audience, the question that guides this study is: What is strategy as practice? Additionally, we structure this systematic review following Callahan’s (2014) critical questions: why, what, where and how, and reformulate them to answer these questions in the following way: Why is it important to know about strategizing? What do we know about strategizing? Where does strategizing research take place? And, How can this review contribute to finding new research opportunities?

During the research, it was possible to identify that this perspective shares the labels “strategizing”, “strategy-as-practice”,”SAP” “S-as-P” and “estrategia como práctica” as keywords. With these criteria, this systematic review was conducted within fifteen different databases in English, Spanish and Portuguese, with articles dated from 1996 to 2017. The update of this review for the years 2018-2019 resulted in 187 new documents, confirming that this field of research has grown in a very significant way. Further, this update merits a separate analysis and text. The starting point of this review was 1996, the date of the seminal work in this perspective: “Strategy as Practice” by Whittington (1996) according to Maia, Di Serio, & Alves Filho (2015).

A total of 180 documents were selected among videos, papers and books. Based on these files we recognized the practice turn as a starting point of this view. It suggests that social life occurs constantly from the actions of people (Feldman & Orlikowski, 2011). Therefore, Feldman and Orlikowski (2011) identified three perspectives of practice: empirical, theoretical and philosophical. The first view focuses on ‘the everyday activity of organizing’ (p.1240); the second perspective reviews how practices are produced, reinforced and changed; finally, the philosophical practice recognizes practices as a result of social practice.

The practice theory on Strategizing explains it as a social activity, accomplished through micro-actions, interactions and negotiations between actors (Jarzabkowski et al., 2007). Crucial to S-as-P is Whittington’s (2006) contribution to identifying the three main categories of Strategizing research: practices, praxis and practitioners. Although various academics emphasize particular aspects of these categories, and propose different theoretical approaches, all of them generally subscribe to this key set of features.

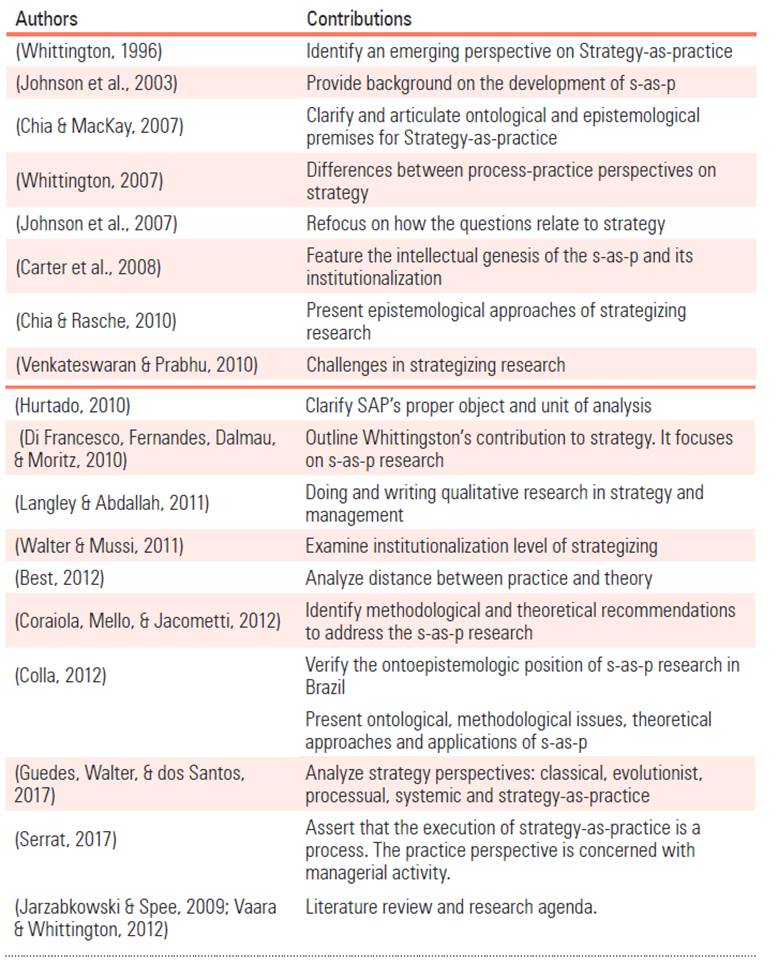

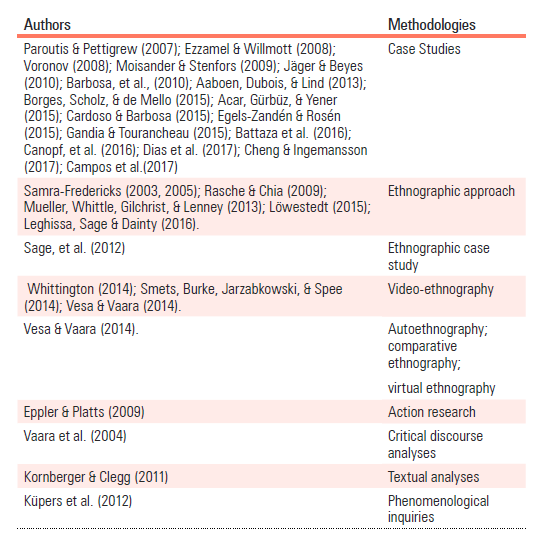

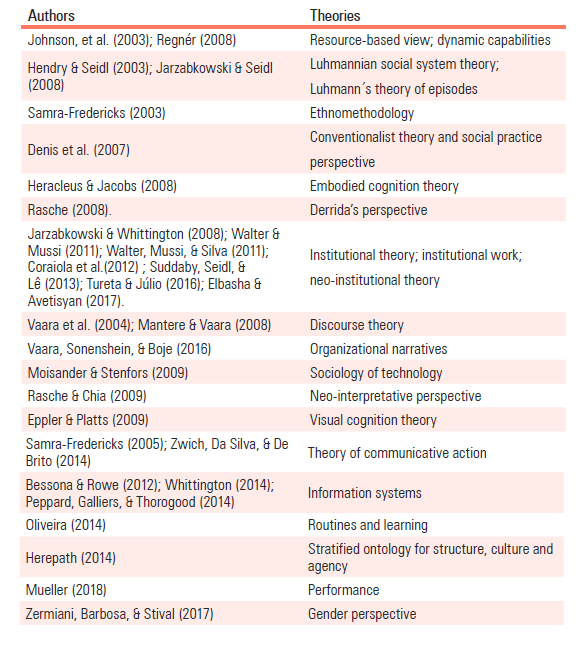

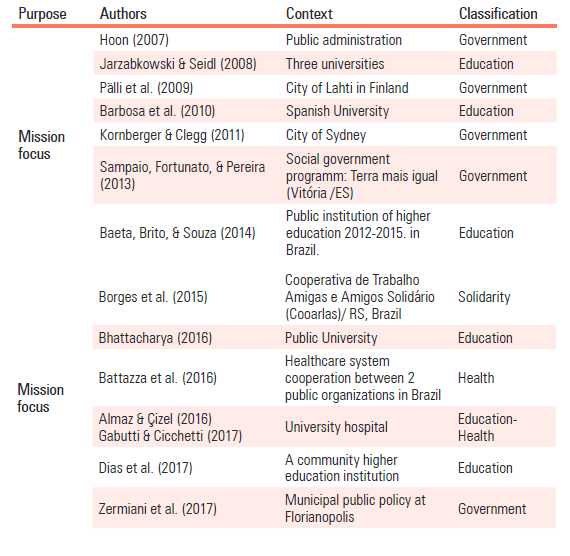

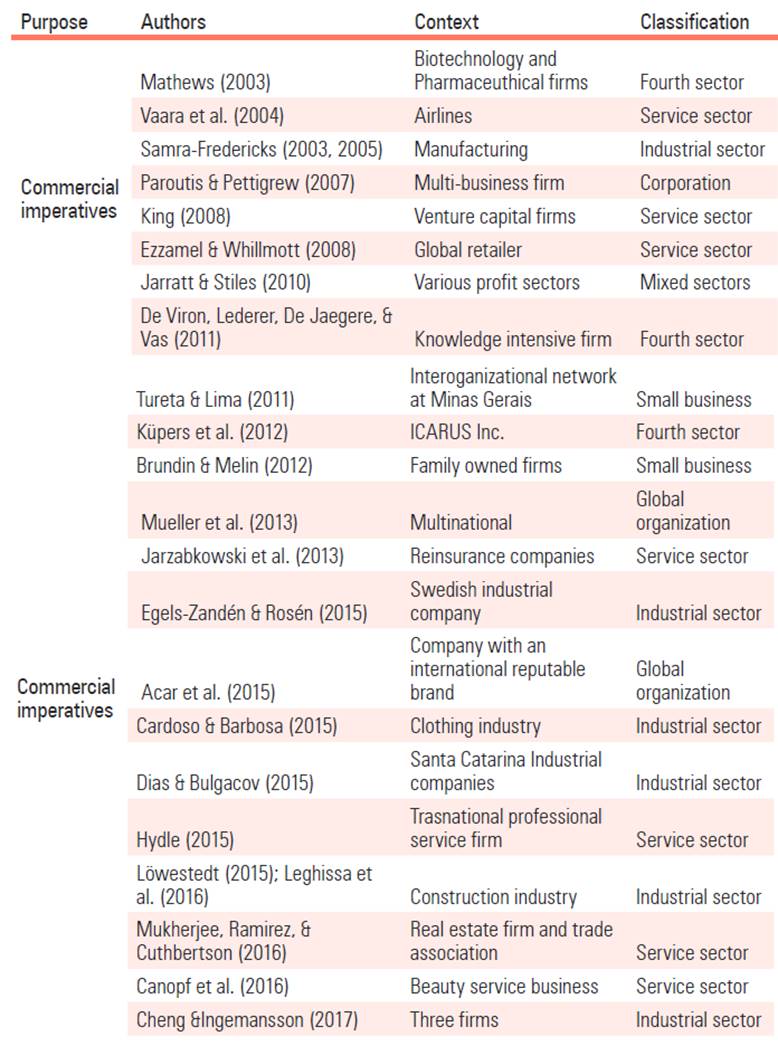

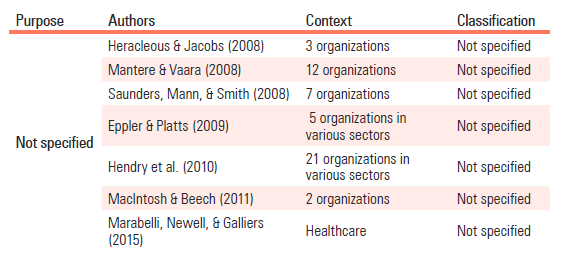

In order to advance towards a theoretical understanding on Strategizing, the practice turn provides a theoretical lens. However, researchers use the practice lens to explain other phenomena (Nicolini & Monteiro, 2016). This is why authors refers to numerous theoretical perspectives. With the aim to register these range of options, we provide a table summarizing them. Empirical studies on S-as-P has been gaining ground within the academic literature. These empirical studies have been oriented by an assorted number of methodological approaches, where case studies dominate (see table 2). To present a landscape of these researches’ contexts, we offer an original classification inspired by Jäger and Beyes (2010) work. It resulted in four groups of contexts: mission focus, commercial imperatives, mixed and not specified (see Tables 4, 5, 6 and 7).

The first section of this text presents the method of this article and main questions that guided this literature review. The second section is related to Why is it important to know about strategizing? and What do we know about strategizing? We present the practice lens, the field of S-as-P, its central categories: practices, praxis and practitioners and its methodologies and theories. The third section answeres the question Where does strategizing research take place? and addresses the contexts of the empirical studies in this field. Finally, the question How does this review identify new research opportunities? as a concluding section, suggests a future agenda in practices and practitioners. With regard to practices, trust emerges as a relevant factor that could contribute to explain the practices’ social nature that is still missing from the literature reviewed. Concerning practitioners, the role of customers is significant in the doing of strategy, but it has been neglected according to this review.

METHOD

The aim of this paper is to provide a concrete starting point for Latin-American scholars for the field of Strategy-as-practice or Strategizing. This comprehensive effort was carried out among fifteen databases (ISI Web of Science, Scopus, Redalyc, Scielo, Latindex, Publindex, Emerald, Science Direct, Springer, Sage, EBSCO, Research Gate, s-as-p.org, Google Scholar and HSTalk) to cover English, Spanish and Portuguese publications. The search focuses on titles, abstracts and key words containing the terms Strategy-as-practice, SAP, S-as-P, Strategizing and Estrategia como práctica over a period of twenty-one years (1996-2017). The starting point of this review was chosen based on the seminal work: “Strategy as Practice” by Richard Whittington (1996) (Maia et al., 2015).

From 307 files, the exclusion criteria for the screening of initial search results were: a. Texts unrelated to Strategizing as a field of research on strategy; b. Texts related to SAP software; and, c. Repeated documents as working papers. This resulted in a sample of 180 documents written by 230 authors. The analytic attention focuses on the abstracts and introductions of the sample.

The central motivation was answering the question: What is strategy as practice? To guide these analyses, we follow Callahan’s (2014) critical questions: why, what, where and how, in order to structure this systematic review. We adapt these questions as follow: Why is it important to know about strategizing? What do we know about strategizing? Where does strategizing research take place? and How can this review contribute to find new research opportunities? and, to answer them in following sections.

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT TO KNOW ABOUT STRATEGIZING?

The conventional perspective on strategy focuses on economic performance, statistical, (Johnson et al., 2007) and macro level analysis (Jarzabkowski, 2005). In contrast, Strategizing privileges what actually takes place in strategic planning and the enactment of strategy (Whittington, 1996). Furthermore, it concentrates on micro-level social analysis, processes and practices (Golsorkhi, Rouleau, Seidl, & Vaara, 2010) or day-to-day activities. It means highlighting what actors do in relation to the context (Jarzabkowski, 2003). Golsorkhi, Rouleau, Seidl, & Vaara (2015) affirm that this approach is a way to understand organizational phenomena with practical relevance, contributing to those who strategize.

In this sense, Strategizing has emerged as a perspective that challenges conventional conceptions of strategy research, as it moves away from the traditional concept of strategy, as something that organizations have, to a practice view of strategy, as something that members of the organizations do (Golsorkhi et al. 2010). Accordingly, Strategizing is understood as an invitation to include human action in the construction and enactment of strategy (Jarzabkowski, Balogun, & Seidl, 2007; Walter & Mussi, 2011). It comprises the interaction of people (Johnson et al., 2007), socio-cultural artefacts that build strategy, (Fenton & Langley, 2011) and the micro-macro ontologies on practice (Seidl & Whittington, 2014). This inductive approach to strategy seeks to interpret practices, praxis and practitioners in daily strategy activity (Heracleous & Jacobs, 2008).

WHAT DO WE KNOW ABOUT STRATEGIZING?

What we know about strategizing is that it stems from the so-called ‘practice turn’ in social science. This postulate considers that actions, processes and practices are attributed to the conscious actors from an ontological assumption (Chia & MacKay, 2007). This means, according to Feldman and Orlikowski (2011), that practices are considered as a lens, with relevance in the understanding of social life as an ongoing production. In its most elemental form, practices can be studied in three different ways: empirically, theoretically and philosophically. An empirical approach answers the ‘what’ question and studies routines and improvised forms of people’s daily activities within an organizational context. A theoretical view entails the ‘how’ question; this approach explains the way in which dynamics of everyday activities are generated or how they operate in dissimilar contexts. The philosophical approach focuses on the ‘why’ question and considers practices as the main component of social reality, which is brought into being through daily activity.

Among studies focusing on the theoretical view, it is possible to refer to philosophers and social scientists. In the first group we find Wittgenstein, Heidegger and Foucault. In the second group we identify Reckwitz, Rouse, Schatzki, Knorr-Cetina, Von Savigny, De Certeau, Giddens, Bourdieu, Garfinkel, Engeström, Miettinen, Punamäki and Vygotsky (Vaara & Whittington, 2012; Walter & Mussi, 2009). Every author has assumed diverse practice conceptions, and this is the root of its lack of epistemological unity (Nicolini & Monteiro, 2016). For example, in the philosophic perspective of practice we can find works based on Wittgenstein language games (Mantere, 2010; Oliveira & Bulgacov, 2013); Heidegger’s social material practice (Chia & Holt, 2006; Tsoukas, 2010); and discourse as part of social practices through which knowledge and power are expressed in Foucault (Allard-Poesi, 2010; Campos, Andrade, Villarta- Neder, & Pimenta-Nascimento, 2017; Ezzamel & Willmott, 2008, 2010; Kornberger & Clegg, 2011; Rodrigues, De Pádua, & Moulin, 2012; Vaara, 2010).

From the social science perspective we trace works towards routinized behavior in Reckwitz (Jarzabkowski et al., 2007); Schatzki questions whether individual actions are the correct foci of social phenomena (Chia & MacKay, 2007); cultural goods from De Certeau (Chia & Rasche, 2010; Rodrigues et al., 2012); procedures, and methods or techniques from a structuralist Giddens perspective (Battazza, Barbosa & Wangenheim, 2016; Elbasha & Wright, 2017; Marietto, Ribeiro & Ribeiro, 2016; Whittington, 2006). The concepts of habitus, capital and field are drawn from Bourdieu (Gomez, 2010; Luo & Wang, 2016; Prieto & Wang, 2010; Splitter & Seidl, 2011).

Chia and MacKay (2007) present a practice perspective as a post-processual view. Firstly, the ontological character is given by the subordination of actors and processes to practices. Secondly, the philosophical commitment explains complexity of practice in ordinary actions and things. Lastly, the locus of engagement is the field of practice and social practices, as knowledge, language and power.

The Strategy as Practice paper by Whittington (1996) motivated the conversation about practice-based view in strategy and ‘to shift the strategy research agenda towards the micro’ (Johnson, Melin, & Whittington, 2003, p. 14). Because of this initiative, there have been numerous works that offer important contributions in this field of research. In Henry Stewart Talks Ltd (HSTalks), we found: works on the background of strategy-as-practice (Jacobs, 2012; Jarzabkowski & Seidl, 2012; Regnér, 2014); the practice perspective on strategy (Clegg, 2012; Langley, 2014; Nicolini, 2012); some categories of strategizing: practices (Cooren, 2012; Jarzabkowski, 2012; Seidl, 2013) and practitioners (Rouleau, 2014; Whittington, 2012) and others about methodological issues (Langley, 2014; Le Baron, 2012). Otherwise, Google Scholar (2017) mentions the following names as the most quoted authors under the S-as-P criteria: Ann Langley, Paula Jarzabkowski, Julia Balogun, Sarah Kaplan and Johanna Moisander. Note that the citations reported by this search engine do not only refer to Strategizing.

As a field of research, the academic community is summoned to discuss methodology, epistemology and ontology issues regarding Strategy-as-practice at: the interest group Strategizing Activities and Practices of the Academy of Management; the Strategy Practice interest group from the Strategic Management Society; European Group for Organizational Studies (EGOS) and Strategy-as-practice’s website: www.sap-in.org (2018). Jarzabkowski & Spee (2009) have identified three foundational books that establish a common terminology: Strategy-as-practice, an activity-based approach by Paula Jarzabkowski (2005); La Fabrique de la stratégie. Une perspective multidimensionnelle by Damon Golsorkhi (2006) and Strategy-as-practice: research directions and resources by Gerry Johnson, Leif Melin and Richard Whittington (2007).

Several of the identified papers contribute to the clarification of this strategic perspective (see Table 1). While some authors present the background on Strategizing, others display ontological, epistemological and methodological frameworks. Some of them present challenges and discussions on S-as-P research, while certain works compare practice with process perspectives on strategy. Finally, various papers propose reviews and research agendas in strategizing.

From these works, we identified Whittington’s (2006) proposal to focus on three central categories on Strategizing: practices, praxis and practitioners. Practices are understood as “shared routines of behavior, including traditions, norms and procedures for thinking, acting and using things” (Whittington, 2006, p.619). Praxis is “the flow of activities in which strategy is accomplished” and practitioners are “those people who do the work of strategy” (Jarzabkowski & Spee, 2009, p. 70, Whittington, 2006).

Practices

Practices are strategic planning, intelligence gathering, annual reviews, business models and budget cycles (Achtenhagen, Melin, & Naldi, 2013; Jarzabkowski & Seidl, 2008; Regnér, 2008). In a broad sense, practices in strategy consists of administrative (Jarzabkowski, 2005), episodic (Hendry & Seidl, 2003) discursive ( Dias, Rosetto & Marinho, 2017; Samra-Fredericks, 2005; Vaara, 2010; Vaara, Kleymann & Seristö, 2004); and narrative practices (De Fina & Georgakopoulou, 2008; Fenton & Langley, 2011; Küpers, Mantere, & Statler, 2012; Rese, Souza, Guedes & Mendes, 2017). Some studies suggest that practices affect not only the way that strategies are developed (Vaara et al., 2004) but also the institutional environment (Tureta & Júlio, 2016). Chia and MacKay (2007) present practices as a relevant concept because they allow us to be human. Practices relate to enabling and constraining effects on strategizing (Vaara & Whittington, 2012).

Practices are more than what people do: they cover the social context where meaning, event and entities are composed (Chia & Holt, 2006). Practices are understood as phenomena that hold a number of activities that make sense according to an end or object. In addition, practices take into account specific material arrangements, have a history and are situated (Nicolini & Monteiro, 2016). Also, they can be identified as discourses, technologies, concepts and models, used in academic and consulting tools. Practices are also embodied in material technologies and artifacts (Jarzabkowski & Whittington, 2008). Some findings indicate that physical artifacts work as embodied metaphors that help to improve creative thinking in strategy (Heracleous & Jacobs, 2008). For example, accounting practices are understood as a discourse with strategic significance (Ezzamel & Willmott, 2008), while strategy is assumed as a textual genre (Pälli, Vaara, & Sorsa, 2009). Some authors assert that practices, such as dialogic strategic planning, are required in pluralistic contexts (Jarzabkowski & Fenton, 2006).

Other practices are understood as visual aids or a method for coping with strategy (Eppler & Platts, 2009). Furthermore, the findings show that social, symbolic and material tools (Cheng & Ingemansson, 2017; Jarzabkowski & Kaplan, 2015; Jarzabkowski & Seidl, 2008) such as Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) analysis have three ways in which to be used: routinized, reflective and engaged (Jarratt & Stiles, 2010). Akgemci, Gungor, & Yilmaz (2016) draw attention to the fact that organizational actors provide tools to place their actions to create and sustain competitive advantage. Following these authors, there are two findings that make it difficult to achieve this advantage: the tools designer does not necessarily understand the tools user culture (Moisander & Stenfors, 2009). As a consequence, practitioners reject the use of tools (Roper & Hodari, 2015).

Practices support diverse positions, protect stabilized relationships and relate to organizational experiences (Jäger & Beyes, 2010). Organizational and culture practices (Sage, Dainty, & Brookes, 2012) and strategic plans (Kornberger, & Clegg, 2011) have effects on power. For example, meetings are practices which can stabilize or destabilize strategies and documents are seen as a contribution to strategic recursiveness of strategizing (Lundgren & Blom, 2014). Finally, given the social nature of the practices, it is remarkable, however, how trust has been neglected in their analysis. Trust is considered the basic element of social life (Luhmann, 2005) and it would deserve a special attention in its influence on strategizing practices.

Praxis

The term praxis is assumed as the performing of everyday activities such as meetings, consulting, writing, presenting, communicating, decision-making, attending workshops, talking, calculating, and form-filling which imply more than the activities themselves (Jarzabkowski & Seidl, 2008; Jarzabkowski & Whittington, 2008; Paroutis & Pettigrew, 2007). Johnson, Balogun and Beech (2010) explain praxis as a way to integrate theory and practice, insomuch as it expresses, in a meaningful way, the ‘local theory’ about what actors are doing, what it means, and why they are doing it. For this reason, praxis is seen as a link between macro and micro context, or as the bond between broader social, economic and political institutions and the local construction of practice (Jarzabkowski, 2005).

Praxis has been examined as an embedded and dynamic concept (Jarzabkowski & Spee, 2009; Jarzabkowski, et al., 2007). The embedded feature indicates that praxis is operated at the micro (individual or groups’ actions), the meso (organizational or sub-organizational flow of actions) and the macro (institutional patterns) levels of analyses. The dynamic property of praxis refers to the fluid interactions between levels. As an example of research at the micro-level of analyses of praxis, Samra-Fredericks has focused on the “everyday interactional constitution of power effects” (2005, p.804) in a corporate context. At the meso-level, Johnson et al. (2010) assert that identity and praxis have a reciprocal relationship; while identity shapes praxis, praxis molds identity and both impact the strategic change at an organizational level. In addition, at the macro-level of praxisDias & Bulgacov (2015) present environmental management based on ISO 14000 in correlation with strategic praxis. In explaining praxis, Vaara and Whittington (2012) assert that it is “what goes on in episodes of Strategy-Making”. Hence, Lopes & António (2012) illustrate how, in the construction of the strategy through a set of actions, interactions and negotiations of various actors, can be translated into positive impacts on organizational performance. While Leghissa, Sage, & Dainty (2016), want to “understand how innovation ‘strategizing’ takes place between firms and suppliers” (p.1068).

Similarly, Canopf, Cassandre, Appio, & Bulgacov (2016) highlight the relevance of experiences when no formal planning is involved and the owner´s logic guides business operations during strategy-making. MacIntosh & Beech (2011) mention the role of fantasy in strategic work while Jarzabkowski, Spee, & Smets (2013) explain material artifacts as epistemic objects for strategizing managers. To understand the strategic company route, Kotler, Berger, & Bickhoff (2010), focus on the knowledge of practitioners for practical considerations. Finally, Samra-Fredericks (2003) highlights the use of emotions, organizational history and metaphors as rhetorical tactics on strategy-making.

Practitioners

As mentioned before, practitioners are the third main category on S-as-P. Practitioners are understood as people involved in making strategy and are seen as “obvious units of analysis for study” (Jarzabkowski, et al., 2007, p.10) because of their active participation in the construction of the strategy starting from who they are, which practices they use and how they act.

Those units of analyses may change depending on whether it is an individual actor (e.g. CEO or MD), aggregate actors (e.g. top managers or middle managers). Furthermore, those actors could be internal or external to the organization (Jarzabkowski & Whittington, 2008; Jarzabkowski & Spee, 2009). Studies on internal organizational practitioners in S-as-P differentiate between top and middle managers’ participation in strategy (Johnson, Balogun & Beech, 2010), including even lower level employees (Jarzabkowski, Balogun, & Seidl, 2007). External practitioners are people who influence strategy, such as consultants, policy makers, media, business schools and gurus (Jarzabkowski & Whittington, 2008). Current studies have observed practices in the new CEO’s post-succession process. In these studies, authors observed CEO’s integration practices in the organization and realigning practices between organization and environment (Ma, Seidl, & Guérard, 2015). As for aggregate actors, such as middle-managers, other authors examine how middle-managers take part in strategic work (Balogun, Huff, & Johnson, 2003). At the same time others have identified the remarkable role of interaction and cooperation within different levels of organizational teams (Paroutis & Pettigrew, 2007).

Other researchers observe the interactions of both top and middle managers from public administration committees and present middle managers as skilled actors (Hoon, 2007). Some scholars, analyze the role that middle managers play on strategic sensemaking, their practical knowledge (Rouleau & Balogun, 2008), their contribution to the integrative strategy formation process of strategizing, (Barbosa, Carnet-Giner, & Peris-Bonet, 2010) and their action on deliberate strategy formation (Cardoso & Barbosa, 2015).

It is surprising that the role of customers has not been properly attended to in this field of research. Customers could be address as external practitioners who, in many occasions, influence the strategy by their market power or by the value proposition of the business model. They can also be seen as internal practitioners when they actively participate in co-creation processes. For example, in B2B relationships (Business to Business), the customer designs its products or services with specific features. Furthermore, in this context, there are not so may, which means having a closer relationship with them, meaning more interactions and negotiations.

The next section presents methodologies, theories and contexts, and an in-depth description of strategizing research.

Methodologies and theories

The increasing attention on Strategy-as-practice has led to empirical studies (Chia & Rasche, 2010) applying a variety of mainly qualitative methodologies (see Table 2 ), mostly case studies, ethnography and ethnographic variations, such as: ethnographic case studies; video-ethnography; auto-ethnography, comparative ethnography and virtual ethnography. While case studies can blend with other methodologies such as ethnography, this table registers separately for descriptive purposes.

S-as-P scholars also take the methodological issue through action research; critical discourse analyses; textual analyses and phenomenological inquiries. Some papers refer to the methodological side by techniques of inquiry (e.g. observation, interviews, shadowing) rather than research methodologies (Ezzamel & Willmott, 2008; Hendry, Kiel, & Nicholson, 2010; Heracleous & Jacobs, 2008; Hoon, 2007; Jarratt & Stiles, 2010; Jarzabkowski & Fenton, 2006; Jarzabkowski & Seidl, 2008; Mantere & Vaara, 2008; Paroutis & Pettigrew, 2007; Vaara & Whittington, 2012).

There are several methodological reflections on Strategizing. Balogun et al. (2003) discuss three approaches that contribute to methodological issues: interactive discussion groups, self-report and practitioner-led research. Golsorkhi, Rouleau, Seidl & Vaara (2015) present a methodological track in their handbook; Langley and Abdallah (2011) explain positivist and interpretative epistemologies, and also practice and discursive turn as four ways of doing and writing qualitative research.

With regard to theories that support strategizing works, we find studies on activity theory (Jarzabkowski, 2003, 2005) and theories of social practices (Denis, Langley, & Rouleau, 2007; Dias et al., 2017; Jarzabkowski, 2004). Also, the critical discourse theory (Vaara, Kleymann, & Seristö, 2004); the Heideggerian perspective (Chia & Holt, 2006), and the systemic approach (Seidl, 2007). Additionally, actor network theory (Denis et al., 2007; Johnson, Langley, Melin, & Whittington, 2007), convention theory (Denis et al, 2007), situated learning (Denis et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2007), discourse practices (Dias et al., 2017), sensemaking perspective (Samra- Fredericks, 2003) and structuration theory (Battazza et al., 2016; Elbasha & Avetisyan, 2017; Marietto et al., 2016; Whittington, 2006) and others that are presented in table 3.

WHERE DOES STRATEGIZING RESEARCH TAKE PLACE?

This literature review examines the particular contexts where organizational processes, activities and practices take place, and are studied from a Strategy-aspractice perspective. Inspired by the text of Jäger and Beyes (2010), the contexts have been classified into four groups of purposes: mission focus, commercial imperatives, mixed and not specified. The organizational characterization depends on the information contained in the papers analyzed. To begin with, the Mission focus classification (see Table 4), refers to the organizational capital composition as government and solidarity and the specific sectors as education and health.

Commercial imperatives (see Table 5), refers to economic sectors such as the primary sector (includes agriculture, mining and natural resources in general); secondary sector (covering industries or goods’ transformation in manufacturing, engineering and construction); tertiary sector (services in finance, tourism, and health, among others) and quaternary sector (intellectual activities). Another kind of classification is based upon the firm size and can be found in small businesses, corporations and global organizations.

The Mixed classification (see Table 6), points out pluralistic organizations. They are concerned with multiple objectives (Denis et al., 2007) as well as solidarity economy and social enterprise.

Table 6 Mixed organizational context

| Purpose | Authors | Context | Classification |

| Jarzabkowski & Fenton | Pluralistic context (3 | ||

| (2006) | organizations) | Pluralistic organizations | |

| Mixed | Denis et al. (2007) | Pluralistic organizations | Pluralistic organizations |

| Jäger & Beyes (2010) | Cooperative bank | Solidarity economy | |

| Rese et al. (2017) | Social enterprise | Social Enterprise |

Source: The authors elaboration.

Finally, not specified (see Table 7), encompasses those papers which do not explicitly state the organizational purpose.

HOW DOES THIS REVIEW IDENTIFY NEW RESEARCH OPPORTUNITIES?

As a conclusion to this article, this question features new avenues to research for Strategizing in Latin America. We recognize that Brazil has advanced in this effort, but in other latitudes there is much work to be done. As stated earlier, Strategizing has become an alternative perspective to mainstream strategy research. It centers its attention on what people actually do during strategic planning and enactment (Whittington, 1996; Golsorkhi et al., 2010). This new perspective looks deeper into micro-level social processes and practices (Golsorkhi et al., 2010), daily actor´s activities in a specific context (Jarzabkowski, 2003), and the interactions that take place in organizations (Johnson et al., 2007). It also pays attention to socio-cultural artefacts that build strategy (Fenton & Langley, 2011).

After reviewing Strategizing´s main categories of practices, praxis and practitioners, we detected research opportunities for practices and practitioners strategizing categories. Practices are located in the social sphere, in this sense, trust as the main factor in social life could help to explain related questions to the practices. Trust focuses on human interactions in organizations and shows the quality of these interactions at micro and macro levels of the organization. In other words, trust could explain how it enables or constrains the actions, interactions and negotiations that take place in strategy practices. In the Paliszkiewicz (2011) literature review, from an organizational perspective, trust is presented as a polysemic concept. The authors reviewed, emphasized expectations, behavior, intention, vulnerability, cognition and dependency, in order to define trust. The authors also assert that trust simplifies negotiation and organizational commitment and it is also “an important predictor of outcomes” (p.316). These review findings foreground the role of trust within organizational life. Important insights could be given by conducting research on the impact that trust has on strategizing practices.

On the other hand, even though practitioners are considered as “obvious units of analysis for study” in Strategizing (Jarzabkowski et al., 2007, p. 10), customers are left aside as there seems to be only one article in this review that even slightly mentions customers (Jarzabkowski et al., 2007; Lowendahl & Revang, 1998). In contrast, there are various articles dedicated to internal practitioners such as top and middle managers and employees, and external players such as consultants, policy makers, media, business schools and gurus.

As Osterwalder, Pigneur, Bernarda, & Smith (2014) state “Understanding the customer’s perspective is crucial to designing great value propositions” (p.1373), and value propositions are central to coherent business models which are understood, “as the conceptual link between strategy, business organization, and systems. The business model as a system shows how the pieces of a business concept fit together, while strategy also includes competition and implementation” (Osterwalder, Pigneur, & Tucci, 2005, p. 10). Following this idea, it was necessary to add business model as a new keyword for strategizing the articles search, and only two were found: The business models found in the practice of strategic decision making: insights from a case study (Hacklin & Wallnofer, 2012); and, Dynamics of Business Models-Strategizing, Critical Capabilities and Activities for Sustained Value Creation (Achtenhagen, Melin, & Naldi, 2013).

Hacklin and Wallnofer (2012) highlight that a business model “reaches out beyond the traditional firm-centric focus, by considering external stakeholders within its conceptual boundaries” (p. 171). This is relevant for today´s business contexts where it is difficult to establish clear inside-outside boundaries between actors participating in the creating-delivering-capturing value cycle. This is why these authors case´s study shows a way to represent their business model, where they established an interface between the inside and the outside boundaries. For instance, they place customer value in the outside, value delivery to the customer in the interface, and internal structure for value creation in the inside. Nonetheless, they do not further develop their findings regarding how relevant it is for the business model to know what customers value most.

Adding to this non-traditional way of seeing business models, Achtenhagen et al. (2013) assert that business models keep changing in order to achieve sustained value creation. They also refer to the fact that some authors define business model in relation to the benefits for customers, and explain them as one of the measurement key variables of their study (New markets/customers). These authors go further in relating business models strategizing toward dynamic capabilities to highlight that “the deployment of different capabilities creates value for customers” (Achtenhagen et al., 2013). But even though they do give examples of customer related activities from the cases studied, they do not include customer questions in a survey that they designed in order to provide practitioners with a tool for self-reflection on how to achieve sustained value creation.

As Hacklin & Wallnofer (2012) state, from an academic perspective, business model “seems to unify previously distinct streams of literature, such as the Resource Based View, the Value Chain Framework, Industrial Organization Economics, Transaction Cost Economics and Strategic Network Theory” (p.172). And, from a strategy practitioner’s perspective, business models inform strategic interacting episodes, providing it “with a common language for strategic thinking as a new perspective” (p.182).

However, these two reviewed strategizing articles regarding business models continued observing customers from a macro level perspective, e.g. customer segment, customer market, and customer value. Strategy as practice provides the empirical, theoretical and/or philosophical lenses (Feldman & Orlikowski, 2011) for a better understanding of customers, from a micro-level analysis, as relevant practitioners for a sustainable firm.

A possible starting point could be a microlevel analysis of the value proposition canvas (Osterwalder et al., 2014), understood not just as an important strategic tool but also as a framework of shared meanings (Hacklin & Wallnofer, 2012). In order to create a relevant value proposition, a customer profile is needed, since it provides for a description of the customer jobs, pains and gains that characterizes the target segment (Osterwalder et al., 2014, p. 9). These authors call, from a practitioner´s perspective, to understand customer profiles “through available data, talking to customers, and to immerse yourself in their world” (p.70). They also encourage observing customers in order to identify which jobs are to be done (Christensen, Hall, Dillon, & Duncan, 2016) and also to opening the opportunity to co-creating with them. This ethnographic approach that characterizes business model innovation, resonates with strategizing, but still lacks a finer grained differentiation between users, beneficiaries, clients, customers and even influencers.

In addition, it could be useful to recognize how organizational practitioners actually take into account user and customer observations, and the talks that they usually have in their daily routines, in order to build value propositions that really fit with customers’ expectations, and not just with survey data about market segments. For example, the co-creation processes in B2B customers could be an interesting area of analysis.