Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Anagramas -Rumbos y sentidos de la comunicación-

Print version ISSN 1692-2522On-line version ISSN 2248-4086

anagramas rumbos sentidos comun. vol.10 no.19 Medellín July/Dec. 2011

ARTÍCULOS

The influence of democracy in the practice of public relations in Spain*

La influencia de la democracia en la práctica de las relaciones públicas en España

Jordi Xifra**

** Pertenece al Departamento de Comunicación Universidad Pompeu Fabra (Barcelona). Correo electrónico: jordi.xifra@upf.edu.

Recibido: 20 de septiembre,

Aprobado: 17 de noviembre.

Abstract

This article presents an exploratory study of the current status of public relations in Spain on the basis of elements and indicators applied to other countries in the study The Global Public Relations Handbook (2009). Spain is one of the most notable absentees from the study; this article therefore fills a hole in current public relations research and theory. The conclusion is that Spain is a country that has undergone radical change, from a dictatorship to one of the world's most democratic systems, substantially transforming its economic system, its culture and its society. This transformation has had a crucial effect on the practice of those professions which have freedom of expression as their legal foundation; one such example is public relations, which has grown from an emerging industry into an established profession.

Key words: Spain; democracy; public relations practice; culture.

RESUMEN

Este artículo presenta un estudio exploratorio del estado actual de las relaciones públicas en España con base en elementos e indicadores aplicados a otros países en el estudio denominado ''The Global Public Relations Handbook'' de 2009. España es uno de los grandes ausentes de este estudio; por lo tanto, este artículo llena un espacio vacío que se presenta actualmente en las investigaciones y la teoría sobre relaciones públicas. La conclusión es que España es un país que ha experimentado un cambio radical desde una dictadura hasta uno de los sistemas más democráticos del mundo, transformando sustancialmente su sistema económico, su cultura y su sociedad. Esta transformación ha tenido un efecto significativo en la práctica de esas profesiones que cuentan con la libertad de expresión como su base legal; un ejemplo de ello son las relaciones públicas que han pasado de ser una industria emergente a una profesión totalmente establecida.

Palabras clave: España, democracia, práctica de las relaciones públicas, cultura.

1. Introduction: History and development of the country

Spain's Iberian Peninsula has been settled for millennia. In fact, some of Europe's most impressive Paleolithic cultural sites are located in Spain, including the famous caves at Altamira that contain spectacular paintings dating from about 15,000 to 25,000 years ago. The Basques, Europe's oldest surviving group, are also the first identifiable people of the peninsula.

Beginning in the ninth century BC, Phoenicians, Greeks, Carthaginians, and Celts entered the Iberian Peninsula. The Romans followed in the second century BC and laid the groundwork for Spain's present language, religion, and laws. Although the Visigoths arrived in the fifth century AD, the last Roman strongholds along the southern coast did not fall until the seventh century AD. In 711, North African Moors sailed across the straits, swept into Andalusia, and within a few years, pushed the Visigoths up the peninsula to the Cantabrian Mountains. The Reconquest –efforts to drive out the Moors– lasted until 1492. By 1512, the unification of present-day Spain was complete.

During the 16th century, Spain became the most powerful nation in Europe, due to the immense wealth derived from its presence in the Americas. But a series of long, costly wars and revolts, capped by the defeat by the English of the ''Invincible Armada'' in 1588, began a steady decline of Spanish power in Europe. Controversy over succession to the throne consumed the country during the 18th century, leading to an occupation by France during the Napoleonic era in the early 1800s, and led to a series of armed conflicts throughout much of the 19th century.

The 19th century saw the revolt and independence of most of Spain's colonies in the Western Hemisphere: three wars over the succession issue; the brief ousting of the monarchy and establishment of the First Republic (1873-74); and, finally, the Spanish-American War (1898), in which Spain lost Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines to the United States. A period of dictatorial rule (1923-31) ended with the establishment of the Second Republic. It was dominated by increasing political polarization, culminating in the leftist Popular Front electoral victory in 1936. Pressures from all sides, coupled with growing and unchecked violence, led to the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in July 1936.

Following the victory of his nationalist forces in 1939, General Francisco Franco ruled a nation exhausted politically and economically. Spain was officially neutral during World War II but followed a pro-Axis policy. Therefore, the victorious Allies isolated Spain at the beginning of the post-war period, and the country did not join the United Nations until 1955. In 1959, under an International Monetary Fund stabilization plan, the country began liberalizing trade and capital flows, particularly foreign direct investment.

Despite the success of economic liberalization, Spain remained the most closed economy in Western Europe–judged by the small measure of foreign trade to economic activity–and the pace of reform slackened during the 1960s as the state remained committed to ''guiding'' the economy. Nevertheless, in the 1960s and 1970s, Spain was transformed into a modern industrial economy with a thriving tourism sector. Its economic expansion led to improved income distribution and helped develop a large middle class. Social changes brought about by economic prosperity and the inflow of new ideas helped set the stage for Spain's transition to democracy during the latter half of the 1970s.

Upon the death of General Franco in November 1975, Franco's personally designated heir Prince Juan Carlos de Borbón y Borbón assumed the titles of king and chief of state. Dissatisfied with the slow pace of post-Franco liberalization, he replaced Franco's last Prime Minister with Adolfo Suarez in July 1976. Suarez entered office promising that elections would be held within one year, and his government moved to enact a series of laws to liberalize the new regime. Spain's first elections since 1936 to the Cortes (Parliament) were held on June 15, 1977. Prime Minister Suarez's Union of the Democratic Centre (UCD), a moderate centre-right coalition, won 34% of the vote and the largest bloc of seats in the Cortes.

Under Suarez, the new Cortes set about drafting a democratic constitution that was overwhelmingly approved by voters in a national referendum in December 1978. Since then, Spain is one of the countries with a higher lever of freedom and democracy, a perfect context for the development of public relations.

The Constitution structures the Spanish State into 17 autonomous communities (Ceuta and Melilla were granted more limited autonomy in the mid-1990s), recognizing and guaranteeing the right to self-government of the nationalities and regions of which it is composed. The premise is based on the indissoluble unity of the Spanish nation. Each region's right to self-autonomy is guaranteed by a Statute of Autonomy. Each has its own parliament, regional president, government, and Supreme Court. Legislative powers vary between the communities.

2. Evolution and definition of public relations as a profession

2.1. Evolution

According to Gutiérrez and Rodríguez (2009), the evolution of public relations in Spain can be divided into five periods: the first public relations campaigns (1953-1960), the decade of associative efforts (1961-1969), the search for the institutionalization of the field (1970-1975), the development under the democratic system (1975-1989), and the recognition of public relations as strategic value (1990 till today).

In 1958 Joaquín Maestre, an employee of the Barcelona-based advertising agency Danis, had a chance meeting with Lucien Matrat when visiting Amberes to attend an advertising congress (Gutiérrez &Rodríguez, 2009). The approaches adopted by Matrat, the French father of European public relations doctrine (Xifra, 2006b), interested Maestre greatly. This Spanish pioneer realized that what had been known until then as ''prestige campaigns'' in his agency were known in the rest of Europe as ''public relations'' actions. Thus, he was the first to use the name ''public relations'' professionally in Spain; in fact, in 1960 he founded the first Spanish public relations firm in Barcelona: S.A.E. de RP (Sociedad Anónima Española de Relaciones Públicas), thereby inaugurating the second stage in the historical evolution of public relations in Spain.

This second stage was characterized by a search for mutual understanding between the first professional associations. Gutiérrez and Rodríguez (2009) divide the history of the association movement into three periods. The first spans the years 1961 to 1965, a period which saw the founding of the Technical Group of Public Relations (Agrupación Técnica de Relaciones Públicas) in Barcelona, and two other Spanish associations: the Spanish Group of Public Relations (Agrupación Española de Relaciones Públicas) in Barcelona and the Spanish Center of Public Relations (Centro Español de Relaciones Públicas) in Madrid. The second period comprises the years 1966-1968, a three-year period marked by the search for professional recognition and in which two events stand out: the holding of the 1st Spanish Public Relations Congress and the annual International Public Relations Association conference in Barcelona. The third period begins in 1969, when the first real efforts to institutionalize public relations are made by the professional community.

It was during this third stage that the Franco government approved laws representing a soft legitimization of public relations:

– 1973 saw the founding of the National Trade Association of Public Relations Managers (Agrupación Sindical Nacional de Técnicos en Relaciones Públicas), within the National Press, Radio, Television and Advertising Association (Sindicato Nacional de Prensa, Radio, Televisión y Publicidad). This move represented (minimum) official recognition, any organization wishing to be recognized as an association having to first join the Trade Union Organization.

– In 1974 the government approved the syllabus for the new Degree in Advertising and Public Relations, as an extension of the former Degree in Advertising (Xifra & Castillo, 2006).

– 1975 saw the Ministry of Information and Tourism create the Official Register of Managers in Public Relations (Registro Oficial de Técnicos en Relaciones Públicas), a voluntary census register which ended with the arrival of democracy.

As one would have expected, the transition from the dictatorial government to democracy, considered throughout the world as an example of political maturity, involved changes on all levels, not just the political, and had an intense influence on the practice of public relations. With this change came the fourth stage outlined by Gutiérrez and Rodríguez (2009). The three-year period spanning from 1975 to 1977 respresented an inflection point, with the introduction of new economic and modernization policies in public administration. Communications services were in increasing demand. Economic growth would be accompanied by increased investment in advertising (Etayo, 2002) and other areas, including marketing and non-commercial communications. ''Institutions and firms needed communication, and this could be contracted through agencies or consultancies, or created through internal structures with qualified professionals. The demand for this type of service explains international public relations agencies opening their first offices during the Eighties'' (Gutiérrez &Rodríguez, 2009, p. 24).

The decade of the Nineties witnessed the reappearance of professional associations, with the creation of two new Spanish organizations at a time when the pioneer associations had disappeared: the Association of Public Relations and Communication Consultants (Asociación de Empresas Consultoras en Relaciones Públicas y Comunicación, ADECEC) and the Association of Communication Directors (Asociación de Directivos de Comunicación, DIRCOM). ADECEC (www.adecec.com) was formed in 1991 by representatives of the public relations consultancies with the highest turnovers. It currently comprises 32 firms and is the industry's most important employers' organization in Spain. DIRCOM (www.dircom.org), for its part, was founded in 1993 and includes among its goals the consolidation of communication as a strategic tool for organizational management.

As Gutiérrez and Rodríguez (2009) conclude, ''the active role of both associations reaffirms the constant growth of this professional sector, and the permanent interest in it attaining a relevant position in organizations'' (p. 26).

2.2. Definitions

With the profession's evolution in Europe and the creation of corporate associations in the old continent's leading countries during the 1950s and 1960s, a conceptualization was formed which obeyed statutory requirements, the statutes of these associations including a definition of the practice of public relations.

All the definitions formulated by the professional associations members of the Confédération Européenne des Relations Publiques (CERP) were recorded in a document compiled by said organization in the autumn of 1974. The aim was to construct a synthetic concept of public relations according to the description formulated in the statutes and regulations of the European national associations.

La Agrupación Española de Relaciones Públicas offered the following definition:

Public relations is the deliberate, planned and continuous effort to establish and preserve mutual understanding between a public or private institution and the groups and people who have direct or indirect relations with them.

It is a strategic and business-oriented definition, which is natural given the fact it was drafted by public relations professionals (Xifra, 2006a).

It was not until this century that Spanish academics first offered a definition of public relations. The occasion was the 1st Inter-university Forum of Public Relations Researchers held in Vic from 2 to 4 July 2003, bringing together scholars and university professors in public relations from around Spain. In an attempt to fill an academic void, a definition was proposed based on the relational/co-creational perspective of public relations popular in North American academic publications at the time (e.g. Botan & Taylor, 2004). This definition was considered the most appropriate because, according to its authors, it pivoted on the only true axis of public relations: the relationship between active subjects and their environment, and not on its publics (Xifra, 2005). The definition was as follows:

Public relations is a scientific discipline which studies the management of communication as a system through which mutual relations for adaptation and integration are established and maintained between an organization or person and its publics.

Since its formulation in 2003, this definition has been adopted by different scholars (e.g., Xifra, 2005; Castillo, 2010). A historical analysis of the definition of public relations in Spain cannot, however, overlook the Spanish legal system's influence on the profession. Although later in this article we will refer to the legal system established by the democratic constitution of 1978, we would like to explain at this point why and how the Franco regime defined public relations in legal terms.

The absence of legislation regulating the practice of public relations is an international phenomenon. The only practical attempts at some form of regulation have focused on providing a definition of the discipline. Laws that have done this have been organic provisions for professional registers, aimed at systematic regulation. There is, however, an apparent gap in the law, as the whole issue is resolved by applying the law on freedom of expression and intellectual copyright.

Desantes (1986) established the following profile of the legal rules affecting public relations:

Spain is a clear example of the above considerations. The first legal definition appeared in Decree 1092/75 of 24 April, formulated by the Official Register of Managers in Public Relations. The above Decree includes the broad concept taken from the statutes of the National Trade Association of Public Relations Managers, according to which public relations is ''that activity which, exercised professionally in a planned and habitual manner, tends to create a reciprocal current of communication, knowledge and understanding between an individual or legal entity and the publics it is aimed at''.

A further definition is found in Decree 2198/1976 of 23 July, which establishes rules for applying the principle of authenticity in advertising material, meaning that messages which are ''public relations information'' (as occurs in advertising) must be clearly differentiated from other news. In the opinion of Desantes (1986), this implies that the legislator considered public relations messages to be necessarily channeled through advertising as a medium, or was unaware of its informative essence, as imposing differential criteria from news involves reducing ''legal'' public relations messages to mere promotional information. This appears somewhat strange given that Francoist ministers and bureaucrats were still in power at the time.

What is more, with said order, the legislator nullified any legal reality with regard to public relations, as its essence lies precisely in presenting itself in an informative manner. The aforementioned legal text stated:

''Public relations information is understood as... that which tends towards the creation and maintenance of effective social communication between an individual or legal entity and its publics, whose objective is to establish a climate of trust between the two and which, considered to be of sufficient general interest by the publics of the publication or media, justifies in the view of the Administration and Management Board of the same, the occupying of the corresponding space with no economic reimbursement. In accordance with that set out in article thirty-eight... of the [now revoked] Printing and Press Act, this information must in all cases identify the source of the information''.

And it continues:

''This obligation also extends to public relations information which, not meeting the aforementioned characteristics, is published with payment corresponding to the space used in the media source. In said case the initials 'P.R.' (public relations) are to appear at the end of the same in inverted commas and no smaller than five millimetres high in the printed media and in overlays, or the full expression 'public relations' when mentioned orally in audiovisual media.''

This is a clear example of the interventionism and censorship on freedom of expression and citizens' right to information typical of the Francoist regime which disappeared shortly before the enactment of the aforementioned decree. An analysis of it shows the contradictions inherent in its content. What is more, however, the reasons given for the Decree not only failed to justify it, but in fact had the exact opposite effect, confessing an attempt to distinguish ''between the function of information for general interest and public relations information'' on the one hand, and ''purely advertising information'' on the other, ''in order to effect the disappearance of any form of covert advertising disguised as general interest information''. As Desantes (1986) argued, advertising does not have to be, nor can be, covert. Public relations messages, whether of general interest or not, have no need to manifest their character, just as propaganda, opinion or news do not, their raison d'etre residing in their very purpose.

3. Public relations education

About 70% of Spain's student population attends state schools or universities. The remainder attend private schools or universities, the great majority of which are run by the Catholic Church. Compulsory education begins with primary school or general basic education for ages 6-14. It is free in state schools and in many private schools, most of which receive government subsidies. Following graduation, students attend either a secondary school offering a general high school diploma or a school of professional education (corresponding to grades 9-12 in the United States) offering a vocational training program. The Spanish university system offers degree and post-graduate programs in all fields--law, sciences, humanities, and medicine--and the advanced technical schools offer programs in engineering and architecture.

Regarding communication studies in Spain, for the almost four decades of Franco's rule (1939-1975), studies and research into communication were characterized by a clear lack of theory, explicit ideological and political censorship and the primacy of the state ''machine'' (Jones, 1997). In actual fact, these characteristics could be applied to any discipline, but, as can be readily imagined, the same control that was exercised over the communications industry (press, radio, cinema and television, in particular) was also applied to the incipient theoretical study of this social phenomenon, due mainly to the regime's need to perpetuate itself in the doctrinal and ideological field.

Because of this censorship and primacy, with the exception of some cases in the field, Spanish research while Franco was in power, specifically into advertising and public relations, was characterized by a lack of scientific and academic rigor and ''reduced to simple publications of conferences, seminars or speeches of a doctrinal nature'' (Jones, 1997, p. 104).

Public relations research in Spain has on the whole been carried out in the academic sphere, which was only possible once the discipline was classed as a university subject. In 1971, an executive order of the government came into force allowing universities to request the formation of their own Information Science Faculties and to offer degrees in Journalism and other social communications media. These institutions would be able to teach ''subjects corresponding to Journalism, Cinematography, Television, Broadcasting and Advertising'', grouping them into three sections or branches – Journalism, Audiovisual Sciences and Advertising.

At a later date and on the basis of this new legislation, the Complutense University of Madrid and the Autonomous University of Barcelona requested and were granted Information Science Faculties under the order of the Spanish Minister of Education (September 17, 1971). The Complutense University of Madrid received authorization for the branches of Journalism, Audiovisual Sciences and Advertising, while the Autonomous University of Barcelona was only initially authorized to teach the branch of Journalism. This branch was expanded in 1972 by a new order which allowed the inclusion of Advertising. Subsequently, in 1974 the government provisionally approved the syllabus for the degree in Advertising and Public Relations, extending the former degree in Advertising.

Despite this background, it was not until August 1991 when the Ministry of Education and Science (MEC) definitively authorized a Degree in Advertising and Public Relations (Xifra & Castillo, 2006). The Spanish university system currently has a Degree in Advertising and Public Relations offered at 32 universities (Xifra & Castillo, 2006). According to data gathered by the MEC, in 2010 over 12,000 students were enrolled on this course in the whole of Spain (MEC, 2010). So, although the Spanish system differs from the Anglo-Saxon one, the government has set up undergraduate public relations education as a major-one of the two main content, alongside advertising, as a degree that is official nationwide.

In light of this data and in line with the Spanish university system structure, one might reasonably believe this to be a mature country in terms of public relations education. However, reality does not permit such optimism because the system is not shored up by a scientific community strong enough to transfer the right knowledge to students. According to MEC data (www.mec.es), 195 scholars are registered in the Audiovisual Communication and Advertising knowledge area, the area to which public relations scholars belong (the Spanish government groups knowledge into what are known as ''knowledge areas''), of whom only 38 (19.48%) are public relations researchers and scholars. It is therefore possible to conclude that public relations teaching in Spain is not unaffected by the global problem pointed to by Botan and Hazleton (2006): ''some 'professors' of public relations with zero academics training in the subject area'' (p. 3).

4. Structure of the industry

As Tilson & Perez (2003) argued, new political, economic, social, and media realities in Spanish society have shaped the course of the public relations profession as it is currently practiced both within institutions and consultancies. ''For example, given the dynamic media environment and growing consumerism in Spain, media relations and corporate identity have assumed greater importance as studies indicate'' (p. 132).

According to the report by the practitioners' association ADECEC (2008), conducted by the market research firm Sigma Dos and based on interviews with 207 public relations practitioners –102 with communications managers at the main Spanish organizations in all industries and 105 with managers and employees of public relations firms– the activity carried out by most public relations firms is that of media relations (96%), followed by corporate communication (90.5%).

The companies further reported that corporate communication (91%) and internal communication (88%) were the most important functions of their communication departments, followed by media relations (86%) and public affairs (84%). Some 68% considered communication to be a strategic factor in their operations (87% conducted corporate communication programs), and 89% evaluated the results of these programs and their corporate image.

There is no national census data as to the number of public relations professionals in Spain; however, Tilson and Perez (2003) reported that about one-third of the 400 members of Catalonia's ''college'' or association of advertising and public relations professionals (headquartered in Barcelona) are public relations practitioners. Unfortunately, there is no data about the number of people involved in public relations industry today.

One of the most interesting results of the ADECEC research (2008) is related to which activities internal communications departments delegate most to public relations firms: image and communication audits (32%) and graphics and fair attendance (31%). Although the first piece of data is a consequence of the cost to organizations of having expert research personnel –which is in fact a global trend in the industry (see, for the United States, Wilcox & Cameron, 2012)– the delegation and outsourcing of technical tasks suggests the high managerial and strategic level of the personnel in public relations departments of Spanish firms. This is something that, as we shall see, is not true of the public domain, where there are no specialist employees in public relations.

The ADECEC (2008) report provides additional insight. Public relations firms in Spain had a turnover of 4.3 billion euros in 2008, and 93% of said firms are controlled by foreign firms. Those firms not controlled by foreign firms are among those with the highest turnover, however. Foreign investment is therefore no guarantee of turnover. The big firms –those with a turnover of over 250,000 euro annually– have on average 26 employees, while the others have an average of 12 employees.

One of the factors providing most evidence of the evolution of Spanish society and its influence on the practice of public relations is gender distribution among public relations practitioners. Some 68% of public relations practitioners are women, 32% men. By contrast, 58% of executive positions are occupied by men, 42% by women. This situation is very similar to that of other countries, such as the US (see Wilcox & Cameron, 2012). This is not evidence of an Americanization of the field, however, but rather of the fact that Spain has the same trends as other western societies.

Although the research conducted by ADECEC (2008) did not analyze the average age of professionals in Spanish public relations departments, it did analyze those of employees at public relations firms. The average age of employees at a firm is 35, with an average antiquity at the firm of 3.3 years. This appears to us to be a fundamental statistic in showing how young the profession is, where the average professional has not grown up and lived in a democratic society. What is more, the dynamism in the industry is shown by the rotation of professionals changing firm or creating their own.

The average salary of a practitioner at a firm is 24,200 euros in the larger firms and 21,200 in a small or medium-sized one. With regard to education, 83% have a university qualification (70% undergraduate and 13% postgraduate).

Tilson and Perez (2003) mention a survey conducted by the Complutense University of Madrid and the Autonomous University of Barcelona in 1999 on behalf of DIRCOM, that reported that there are some 50 different designations for the department, ranging from ''Public Affairs'' to ''News'' to ''External or Public Relations.'' Interestingly, the word ''Communication'' appeared in 70.6% of the corporate department names. In some circles, generally speaking, the designation ''public relations'' still has a negative connotation as historically some practitioners have associated themselves with superficial responsibilities, ranging from organizing cocktail parties to beauty and cosmetic promotions. There is no information of the current situation, but there are no motives for thinking that the situation points very different today.

5. Infrastructure and public relations

5.1. The political system

Parliamentary democracy was restored following the death of General Franco in 1975, who had ruled since the end of the civil war in 1939. The 1978 constitution established Spain as a parliamentary monarchy, with the prime minister responsible to the bicameral Cortes (Congress of Deputies and Senate) elected every 4 years. On February 23, 1981, rebel elements among the security forces seized the Cortes and tried to impose a military-backed government. However, the great majority of the military forces remained loyal to King Juan Carlos, who used his personal authority to put down the bloodless coup attempt.

In October 1982, the Spanish Socialist Workers Party (PSOE), led by Felipe Gonzalez, swept both the Congress of Deputies and Senate, winning an absolute majority. Gonzalez and the PSOE ruled for the next 13 years. During that period, Spain joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the European Community.

In March 1996, Jose Maria Aznar's Popular Party (PP) won a plurality of votes. Aznar moved to decentralize powers to the regions and liberalize the economy, with a program of privatization, labor market reform, and measures designed to increase competition in selected markets. During Aznar's first term, Spain fully integrated into European institutions, qualifying for the European Monetary Union. During this period, Spain participated, along with the United States and other NATO allies, in military operations in the former Yugoslavia. President Aznar and the PP won re-election in March 2000, obtaining absolute majorities in both houses of parliament.

After the terrorist attacks on the U.S. on September 11, 2001, President Aznar became a key ally in the fight against terrorism. Spain backed the military action against the Taliban in Afghanistan and took a leadership role within the European Union (EU) in pushing for increased international cooperation on terrorism. The Aznar administration, with a rotating seat on the UN Security Council, supported the intervention in Iraq.

Spanish parliamentary elections on March 14, 2004 came only three days after a devastating terrorist attack on Madrid commuter rail lines that killed 191 and wounded over 1,400. With large voter turnout, PSOE won the election and its leader, Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero, took office on April 17, 2004. The Zapatero government has supported coalition efforts in Afghanistan, including maintaining troop support for 2004 elections, supported reconstruction efforts in Haiti, and cooperated on counter terrorism issues. Carrying out campaign promises, it immediately withdrew Spanish forces from Iraq but has continued to support Iraq reconstruction efforts.

Form a political standpoint, Spain has been a country in political, societal and economic transition. Without a doubt, in the political level, this condition has intensely affected public relations profession, particularly with the emergence of the profession of political consultant which, with most trained at American universities, has become one of the most sought after professional areas given the high number of elections held in Spain: European, national, regional and local (Aira, 2009).

With regard to public relations campaigns run by public institutions, it is mainly private firms which are contracted. The Spanish government does not have public employees specialized in public relations. The only professionals working in public relations are chiefs of staff or general secretaries, these tending to be ex-journalists who have established a relationship of trust with the government. For this reason, most public relations work carried out by the Spanish public administration falls within media relations (Xifra, 2009). However, the role of spokesperson is conducted by politicians and high ranking public employees themselves.

5.2. Economic development

When the Spanish Civil War ended in 1939, a period began which was characterized by the absence of democracy, isolationism from the rest of the world, very strong state control and an economy burdened by the inefficiencies of the public sector and corruption. This period lasted until 1959, when the first National Economic Stabilization Plan opened the country up to foreign markets and firms. Multinational firms began to move into Spain on a large scale and the economy experienced significant growth. GDP began to grow at rates of around 7%.

In 1973, the transition to democracy began and the dictatorship ended in 1975. This phase coincided with an important international economic crisis, known as the ''oil crisis''. As a consequence, Spain experienced lower growth in its GDP, significant increases in inflation rates and considerable growth in unemployment.

We agree with Gutiérrez and Rodríguez (2009) when they state that the political and economic context at the end of the Franco dictatorship helped firms to introduce themselves to an increasingly more open society. The improved economic context with the economic stabilization plans (implemented with the help of the United States) also influenced and ensured the first company clients for the first public relations consultancies.

With the arrival of democracy, another circumstance common in other countries explains why firms and institutions created their communicative structures: the progressive consolidation of a free market regime and therefore one with more products and services on offer and necessary differentiation between businesses (Sotelo, 2004).

''Until the end of the Eighties, important economic and business sectors –telecommunications, energy, transport, etc.– were state monopolies. Furthermore, in the supply of certain products and services there existed a legal framework that made some sectors –especially the financial one– conduct its activity under marked regulation. However, the legal and economic framework in the final decades of the twentieth century changed substantially, situating firms in a new economic and social scenario'' (Gutiérrez & Rodríguez, 2009, p. 22-23).

Later, in 1986, Spain joined the European Economic Community, leading to increased competition and traumatic restructuring in many sectors of the economy. By way of contrast, structural funds from the EEC allowed the modernizing of infrastructures and the existing standard of education. Since 1990 and up until the present day, a strong movement to liberalize the economy has prevailed, with the privatization of firms in regulated industries such as electricity, gas and water. Many of these firms together with the big banks then began to invest in Latin America. With the arrival of the international economic crisis of 2008, the Spanish economy entered a serious recession.

These fluctuations in the economy had an effect on the practice of public relations, which during the 1980s was a flourishing activity developing extraordinarily up until 1992, thanks to the holding of two events of worldwide significance in Spain: the Barcelona Olympics and the Seville Expo. Media relations and event management were the activities that most occupied public relations firms, which had doubled in number at the beginning of the 1990s in comparison to 1980 (Arceo, 2004). The crises of 1993 and 2008 have meant that the practice of public relations has had to adapt, although as we have seen with the structure of the practice, is a consolidated profession. Nevertheless, it is actually the current rate of unemployment, close to 20% (2011 est.), that represents the main sword of Damocles hanging over the profession in Spain.

5.3. Activism

The arrival of democracy did not bring an end to political activism, although it was limited to the terrorism of the Basque independentist group ETA. However, during the early years, particularly between 1976 and 1978, that is, before the approval of the new democratic constitution at the end of 1978, some groups did demonstrate for an urgent recognition of civil rights (for example, the right to free abortion) or nationalist rights (for example, demonstrations to claim autonomy for historical regions such as Catalonia and the Basque Country). Another demand was that of amnesty for political prisoners of Francoism, which generated numerous grassroots mobilizations and public demonstrations.

Nowadays, despite a solid democratic system, activism centres around political activism aimed at obtaining greater recognition for political and financial autonomy for regions such as the Basque Country and Catalonia. Although the terrorist group ETA has not relinquished its arms (a ceasefire has been in place since September 2010), pacific independentist activism does exist and manifests itself regularly in the streets of cities such as Bilbao and San Sebastián. In Catalonia, the nationalist movement is represented by both the autonomous government and important groups in civil society.

In addition to this, 15 May 2011 witnessed a spontaneous demonstration in Madrid and Barcelona by the group now known as ''15-M'' (in reference to the date), better known as ''the indignants''. This represented the largest demonstration of activism since the end of the 1970s. This group, which has no formal structure, unites people of any age and status who are indignant at the economic situation deriving from the 2008 crisis and the measures that the Spanish government has, or has not, taken to resolve it.

This appears to have brought to an end investigations demonstrating that the level of activism in Spain is lower than that in the other EU countries (e.g. Anduiza et al, 2010), even though the lack of clear organization among the indignants has proved damaging to their claims. One example of this is the lack of spokespeople when presenting their claims/decisions to journalists: a new member almost always appeared when it was time to deal with the media.

This implies that activism has not had much influence on the practice of public relations in Spain. As already mentioned, large-scale social movements have not had an effective communications strategy behind them, and neither have corporations had to invest time and effort in managing their relations with activists. As highlighted by the director of public relations for the country's largest energy corporation upon announcing a project to install a high-voltage line in Catalonia to transport energy from France to Spain, ''more than with ecologists and activists, with whom we have not had any formal communication, our interest was to inform journalists of the need for this public installation''.

5.4. Legal system

The Spanish constitution of 1978 is one of the most advanced of its age, especially with regard to recognizing citizens' rights and liberties. With regard to the practice of public relations, the most relevant aspect is freedom of expression and recognizing the right to information (of citizens) and the right to information (of the mass media) with the sole limitation of respecting the honor, personal intimacy and image of individuals.

As Gutiérrez and Fernández (2009) point out, freedom of expression and the right to information, along with economic liberalization, put firms and institutions in a position whereby they had to respond to a very different environment to the one they were accustomed to. A more dynamic environment with complex communicative relationships. Within this context, it was the business community that demonstrated greater vitality in organizing its communicative functions. Facing a greater supply of products and services, firms must offer a corporate message that differentiates them from the market and, above all, transmits their corporate identity unambiguously. For their part, public institutions and non-profit organizations have seen their role in the public domain progressively strengthened with a communicative policy that responded to the obligation to inform (Gutiérrez &Fernández, 2009), that is, to citizens' right to be informed.

With regard to citizens' rights, freedom of expression is concretely articulated in the realization of the possibilities recognized by the constitution: expressing any thoughts, idea, belief, value judgment or opinion, that is, anyone's subjective perception, and publishing it through any medium, whether natural (words, gestures) or any technical medium for reproduction (written, on the airwaves...), as specified by the Supreme Court of Spain.

In relation to the broadcasting and publication of opinions, the Supreme Court has stated that freedom of expression protects not only the expression of opinions which are ''inoffensive or indifferent, or those which are received favorably, but also those that might cause concern to the state or part of the population, as this is the result of pluralism, tolerance and the spirit of openness without which a democratic society does not exist'' (Sanjurjo, 2010, p. 123). The Supreme Court has repeatedly interpreted freedom of expression to cover criticism, for example, of those in public positions, including upsetting or harmful criticism, whilst warning that criticism of a person's conduct does not admit the use of formally injurious or unnecessary expressions, which remain outside the protection of freedom of expression.

Public relations cannot fully operate without freedom of expression. In three short years Spain witnessed a transition from an absence of freedom, persuasive messages being restricted to Francoist propaganda and commercial advertising, to a democratic situation in which the practice of public relations has ultimately become the main source of information for the mass media (Xifra, 2009).

6. Culture and public relations

Spain is a country which in recent decades has undergone spectacular political, economic and consequently cultural change. It therefore constitutes an interesting testing ground for verifying the validity of the cultural dimensions formulated by Hosftede (2001).

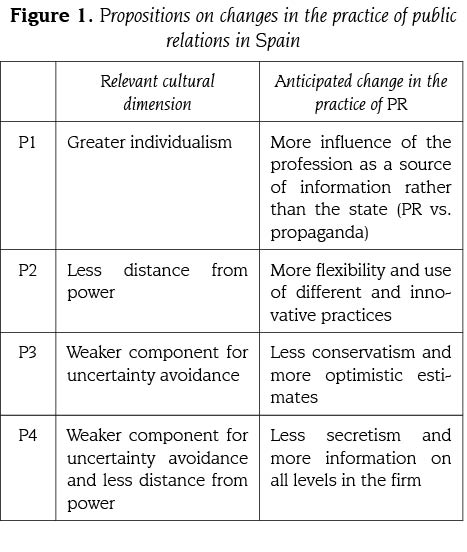

As a consequence of the transition from a dictatorship to a democracy, the cultural changes in Spain may be approached in the form of propositions as follows:

Figure 1 shows the changes that can be anticipated in public relations practice for Spain in the form of propositions.

For Spain's classification in Hofstede's work (2001), the dimensions power distance comes in position 19 (from a total of 39), individualism in position 20 and uncertainty avoidance in position 6. Firstly, it seems likely that Spain is headed less towards ''distance from power'' and more towards ''individualism.'' Furthermore, the country's marked tendency to avoid uncertainty may indicate the likelihood of few changes in this cultural dimension. Therefore, of the propositions summarized in Figure 1, it is more likely that the former two, which are based on the dimensions distance from power and individualism, will be met than the latter two, which are based on uncertainty avoidance.

Let us now analyze the degree of fulfilment for the case of public relations for each of the propositions.

P1: Greater individualism-more influence of the profession.Without doubt, the transition from the dictatorship to democracy has represented a change in the Spanish public domain, whereby propaganda (which continues to exist, especially in the political and electoral arena) has given rise to corporate communication and public relations strategies in public communications management. Furthermore, as already mentioned, public relations campaigns by public administrations involve the contracting of public relations firms. There are no public employees specialized in public relations in Spain. The only area that is addressed by public administration itself is that of media relations, the responsibility for which tends to fall on former journalists in positions of trust with public managers (ministers, chiefs of directorates...).

P2: Less distance from power – more flexibility.The arrival of freedoms in Spain extended to society as a whole. Firms could not be exempt from this. One particularly surprising case of increased flexibility has been the rupture from any lack of freedom of expression, but always respecting other fundamental rights such as the honor, image and intimacy of people and organizations.

P3: Less uncertainty avoidance – more optimistic estimates. Although public relations practitioners are less optimistic than in 2004 (when 84% thought that the industry would grow), those who think that the industry will continue to grow represent 69%, and only 5% think it will decrease in size (ADECEC, 2008). That said, it is important to remember that Spain's initial starting point has a such a strong component for avoiding uncertainty (the dictatorship) that it is unlikely the democratic transition will weaken it, meaning it is probable the uncertainty avoidance Index (UAI) will remain a strong general factor.

P4: Less uncertainty avoidance and less distance from power – more information on all levels in the firm.The ADECEC (2008) report appears to shed some light on this proposition. One piece of data is especially relevant in reference to the relationship existing between internal departments and public relations firms: in 43% of cases the the department and the firm have daily contact and in 19% of cases contact is weekly. This is evidence of the existence of less distance from power and greater transparency and information on all levels.

7. The media and public relations

7.1. Media control

During Francoism, the media were a propaganda instrument in the service of the regime. The rise of new media groups during the transition, in both Madrid (Prisa, Grupo 16, Recoletos) and Barcelona (Zeta), had a serious effect on the ideological influence and economic benefits of the media established during Franco's regime, the latter unable to compete due to their obsolete media model, antiquated machinery, not having sufficient capital and an excessively large workforce, at times with little professional and technical training.

This process gradually caused a chain reaction, provoking the dismantling of the old Prensa del Movimiento (the group founded by the Francoist regime in 1940), which was sold at public auction in 1984. The new actors in the media system staked their claim to inaugurate the private radio and television business (inexistent until almost a decade later) in a first attempt to diversify their activities on the media market. However, their lobbying efforts on the Spanish government were not enough and other public actors appeared before them: Euskal Irrati Telebista (EITB, the Basque TV group) and Corporació Catalana de Ràdio i Televisió (CCRTV, the Catalan TV group).

With Spain's integration into the European Union the country's legislation became more liberal, allowing the entry of European capital into practically all economic macro-sectors, including media and culture, something which accentuated the denationalization of the Spanish economy, with decisions being taken at increasingly more distance from the country itself (Jones, 2004). The Eighties also witnessed the arrival of new radio stations in Spain (e.g. Antena 3 Radio and Radio 80) and, from 1990 onwards, three new television stations (Antena 3 Televisión, Gestevisión Telecinco and Sogecable [Canal Plus, Pay Per View]). The number of firms increased after 1997 due to two new digital satellite platforms (belonging to Sogecable and Telefónica), which eventually merged in 2003. The main shareholders in these new television channels were Catalan groups, such as Godó and Zeta, although both ended up transferring their shares to Madrid (Prisa, Telefónica de Contenidos), Basque-Madrid (Vocento) or foreign groups (Mediaset, Vivendi Universal, Kirch, Bertelsmann).

7.2. Media access and media relations

The Spanish constitution guarantees freedom of expression, which for some authors (e.g. Sanjurjo, 2010) includes the right of access to the media. This right to access is founded on article 20.3 of the constitution, which establishes that:

''the law will govern parliamentary organization and control of the social media dependant on the state or any public body and guarantee access to said media for important social and political groups''.

The Supreme Court of Spain has stated that this article contains a mandate awarding important social and political groups the right to demand that nothing be done to impede said access. In accordance with this flexibility, the Spanish legislator has established different opportunities for accessing the mass media, especially for important social and political groups, who have the right to a percentage of broadcasting hours on both public and private television channels. What is more, cable operators, who are franchise owners, must reserve 40% of the time broadcast on their network for independent programmers. Finally, Spanish law awards political groups direct access to the public media via unpaid broadcasting time for electoral messages, while the private media are requested to respect pluralism.

We have already stated that media relations is one of the principal activities for Spanish public relations practitioners. In their analysis of media relations in Korea, Kim and Hon (1998) pointed out that Korean practitioners are practicing one-way models mainly focused on media relations because of the tradition of source–media collaboration under authoritative regimes in the country's developmental period. Despite the 40 years of the Franco dictatorship, the above reasons do not appear to affect Spanish practitioners who, as occurs in other countries, make characteristic errors of the one way practice of media relations (Xifra, 2009). Despite this, however, Spanish journalists did not perceive practitioners to lack professionalism and to be deficient in the quality of subsidies on a number of counts, particularly if we compare this with similar studies conducted in other countries (e.g., Sallot & Jonson, 2006).

The results and opinions arising from the research conducted by Xifra (2009) offer a more dialogic dimension of media relations in Spain than in other countries and nations. The relevance of one way channels and the effectiveness of online press rooms demonstrate a tendency to foster dialogic and interactive channels which form part of the public (media) relations relational perspective. This tendency is also observed in the needs expressed by journalists, all of which are based on a mutually beneficial personal relationship between the public relations practitioner and the journalist.

Some media relations studies have related personal relationships with the Hofstede's idea of power distance (Hofstede, 2001). As Taylor pointed out in her research on Croatian public relations, a ''related factor that may influence the development of personal relationships in the nations of the former East Bloc is the development of strong, personal relationships'' (2004, p. 157). From this standpoint, personal influence may best characterize this relational strategy. The personal influence model proposed by Sriramesh (1992, 1996) is an example. Personal influence is based on a cultural variable of power distance. According to Hofstede (2001), Spain displays high levels of power distance in its social systems. The mean score for 39 countries on power distance is 51 and the score for Spain is 62.

The results obtained by Xifra (2009) research suggest that journalists require a relational perspective of media relations. They demand media relations practiced through personal relationships and rich communication channels. These personal relationships may be based on long-standing friendships between journalists and public relations people or they may be cultivated over time through frequent and rich face-to-face communication and reciprocity. The data also show that organizations practice a version of Sriramesh's personal influence model. Nevertheless, and this is also relevant, there is no significant evidence of any distrust existing between media relations parties. Journalists consider the main mistakes made in public relations subsidies to be errors and not attempts at manipulation: a success of how new Spanish democratic society has influenced media relations practice.

8. Conclusions

The radical political transformation Spain has undergone over the last 30 years has made it a country in transition; the transition from a capitalist dictatorship to a democratic state is, after all, very similar to the transition from a communist dictatorship, as has happened in Poland (see Lawniczak et al. , 2009), the main difference being an economic one. That aside, we have seen how the economic transformations resulting from the arrival of democracy in Spain have also been important.

Although the Franco regime's propaganda was very powerful in its time, the regime's influence seems to have disappeared almost entirely as a factor influencing the practice of public relations. The freedoms of expression and opinion safeguarded under the Spanish constitution have radically changed the scenario for communicative practices. From among these, public relations has emerged as a new profession establishing itself at the same time as the modern and democratic Spanish society has itself become consolidated. This is an example of why public relations is not only a democratic function, but is actually ontologically democratic.

With regard to culture, there is also sufficient evidence relating the evolution of cultural variables to changes in the practice of public relations. In Spain, we might expect greater individualism (more influence of the profession rather than state control and guidance), less distance from power (more flexibility and more diverse and innovative practices), less uncertainty avoidance (less conservatism and more optimistic estimates) and less secretism. Of these hypotheses, there would seem to be solid evidence for a greater influence of the profession, the use of more diverse and innovative practices and less secretism.

By way of summary, over recent decades Spain has undergone radical change from a dictatorship to one of the world's most democratic countries, a transformation which has substantially affected its economic system, its culture and its society. And one which has also affected the practice of those professions which have their legal foundation in freedom of expression, like public relations, which itself has transformed from an emerging industry to an established profession. However, Spain includes within its borders regions with their own language and culture. This factor offers an opportunity for future research into how these different cultures affect the practice of public relations within Spain and whether it is possible to speak of different practices for specific cultures, such as the Catalan, the Basque or even the Andalusian culture, as opposed to a Spanish national culture.

References

ADECEC (Asociación de Empresas Consultoras en Relaciones Públicas y Comunicación). (2008). La comunicación y las relaciones públicas: Radiografía del sector. Barcelona: ADECEC. [ Links ]

Aira, T. (2009). Los spin doctors: Cómo mueven los hilos los asesores de los líderes políticos. Barcelona: Editorial UOC. [ Links ]

Anduiza, E., Gallego, A., & Cantijoch M. (2010). Online political participation in Spain: the impact of traditional and online resources. Journal of Information Technologies and Politics, 7 (4), 356-368. [ Links ]

Arceo, J. L. (2004). Las relaciones públicas en España. Madrid: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Beneyto, J. (1957). ''Mass Communications''. Un panorama de los Medios de Información en la Sociedad Moderna. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Europeos. [ Links ]

Botan C. H., & Hazleton, V. (2006). Public relations in a new age. In C. H. Botan and V. Hazleton. Public Relations Theory II, p. 1-18. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Botan, G. M., & Taylor, M. (2004). Public Relations: State of the Field. Journal of Communication, December, 645-661. [ Links ]

Castillo, A. (2010). Introducción a las relaciones públicas. Málaga: Instituto de Investigación en Relaciones Públicas. [ Links ]

Desantes, J. M. (1986). Un concepto jurídico de relaciones públicas. In J. R. Sánchez-Guzmán (ed.). Tratado general de Relaciones Públicas (pp. 93-144). Madrid: Fundación Universidad y Empresa. [ Links ]

Etayo, C. (2002). Advertising in Spain. In I. Kloss (ed.). More advertising worldwide (p. 238-269). Berlin: Springer. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez, E., & Rodríguez, N. (2009). Cincuenta años de Relaciones Públicas en España. De la propaganda y la publicidad a la gestión de la reputación. Doxa Comunicación, 9, 13-33. [ Links ]

Hofstede, G. (2001). Cultures consequences: International differences in work-related values (rev. ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Kim, Y., & Hon, L. (1998). Craft and professional models of public relations and their relation to job satisfaction among Korean public relations practitioners. Journal of Public Relations Research, 10 (3), 155–175. [ Links ]

Jones, D. E. (1997). Investigació sobre comunicació social a l'Espanya de les autonomies. Análisi, Quaderns de Comunicació i Cultura, 21, 101-120. [ Links ]

Jones, D. E. (2004). La globalización comunicativa en Cataluña: Procesos y tendencias. Zer: Revista de Estudios de Comunicación, 16, 27-43. [ Links ]

Lawniczak, R., Rydzak, W., & Trebecki, J. (2009). Public relations in an economy ands society in transition: The case of Poland. In K. Sriramesh, & D. Vercic (eds.). The Global Public Relations Handbook: Theory, research and practice (p. 503-526). New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

MEC (Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia). (2010). Datos y cifras del sistema universitario. Madrid: MEC. [ Links ]

Sallot, L. M., & Johnson, E. A. (2006). To contact... or not? Investigating journalists' assessments of public relations subsidies and contact preferentes. Public Relations Review, 32 (1), 83-86. [ Links ]

Sanjurjo, B. (2010). Manual de derecho de la información. Madrid: Dykinson. [ Links ]

Sotelo, C. (2004). Historia de la gestión de la comunicación en las organizaciones. In J.C. Losada (coord.). Gestión de la comunicación en las organizaciones (pp. 35-56) . Barcelona: Ariel. [ Links ]

Sriramesh, K. (1992). Societal culture and public relations: Ethnographic evidence from India. Public Relations Review, 18, 201–211. [ Links ]

Sriramesh, K. (1996). Power distance and public relations: An ethnographic study of Southern Indian organizations. In H. M. Culbertson & N. Chen (Eds.), International public relations: A comparative analysis (pp. 171–190). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Sriramesh, K., &Vercic, D. (eds.) (2009). The Global Public Relations Handbook: Theory, research and practice. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Taylor, M. (2004). Exploring public relations in Croatia through relational communication and media richness theories. Public Relations Review, 30 (2), 145-160. [ Links ]

Tilson, D. J., & Perez, P. S. (2003). Public relations and the new golden age of Spain: A confluence of democracy, economic development and the media. Public Relations Review, 29 (2), 125-143. [ Links ]

Wilcox, D. L., & Cameron, G. T. (2012). Public relations: Strategies and Tactics. Boston: Pearson, 10th ed. [ Links ]

Xifra, J. (2005). Planificación estratégica de las relaciones públicas. Barcelona: Paidós. [ Links ]

Xifra, J. (2006a). ¿Es marketing todo lo que reluce? La pluralidad de perspectivas conceptuales de las relaciones públicas. Análisi, Quaderns de Comunicació i Cultura, 34, 163-190 [ Links ]

Xifra, J. (2006b). Pioneros e ignorados: La escuela de Paris y la doctrina europea de las relaciones públicas. Ámbitos, Revista Andaluza de Comunicación, 15, 449-460. [ Links ]

Xifra, J., & Castillo, A. (2006). Forty years of doctoral public relations research in Spain: A quantitative study of dissertation contribution to theory development. Public Relations Review, 32 (3), 302-308. [ Links ]

Xifra, J. (2009). Journalists' assessments of public relations subsidies and contact preferences: Exploring the situation in Spain. Public Relations Review, 35 (4), 426-428. [ Links ]

Notas:

* El artículo es fruto de una indagación elaborada por el autor, y que ha sido llevada a cabo en su rol de investigador del Grupo UNICA de la Universidad Pompeu Fabra.