Introduction

Advertising communication, as indicated in the first half of this paper’s title, suggests a kind of message in society with a form of distinctions. The peculiarities of the communication are multimodal in nature. Multimodality serves as a platform where advertising professionals make positive claims about goods and services for a persuasive purpose irrespective of the products’ sources of production and functions. Having been foresighted, the claims of the textual creators are not in exclusion of social parameters (Brierley, 1995; van Dijk, 2010) that recipients are already acclimatized with. Nonetheless, the anonymous audience sometimes detest the message and take the information meant for reasoning for granted owing to the manifestation of advertisements (henceforth: ad/ads) in domains of events (Dyer, 2005; Goldstein & McAfee, 2013; De Sa, Navalpakkam & Churchill, 2013; O’Donnell, 2015; Chang-Hoan & Hongsik, 2015). This, perhaps, influences advertising communicators to adapt a strategy that can fascinate the public to consumption. In ad dition to that, the behaviors of the recipients toward ads might have contributed to the complexity of the constructs experienced in advertising plates. It is on that ground, one could remark, that the thought of brevity in advertising has become normative as well as disjunctive most times. Apart from the disjunctive facilities sounding poetic sometimes, it is remarkable that the communicative texts try as much as possible to accommodate other models of writing styles (Carter & Nash, 1990; Cook, 2001; Fairclough, 2001) to fulfill a persuasive purpose.

The advertising professionals do a lot with texts in the course of attracting the public towards the products. In the perspective of Myers (1994), the activities of these communicators in language deployment are classified into:

The demands of brevity, the relations of text and pictures, the semantics and associations and legal status of words; the implications of phrases, the effects of style, the side-stepping of taboos, and most of all, the unpredictability of the effects (p. 2).

The advertising practitioners being seemingly quick-witted individuals, Myers accentuates that the concern of social issues are fundamental in the advertising craft, as it is in human lives (De Paula & Fernandes, 2016; Dalamu, 2017d). As much as advertisers are interested is selling a product at all cost and by all means, considerations are given to the contents of the message in relation to the products, consumers, and the legality of the information distributed in the public sphere. Outside the legal implications, the study prides itself in brevity, which Shakespeare (2003) constructs as the soul of wit. This is a research that has attempted to explore forms of segmented units in advertising frames in Nigeria to necessitate meanings to readers. Despite that most of the structures are not perfectly sentential, the message intended is not lost. The analyst has also set out to investigate the parts of the linguistic elements of the clause commonly deployed for excitement, and why is it so.

Language and Communication

In the insight of the author, the vitality of language and communication positions the two devices to operate in a similar boundary of human socio-cultural activities. This is on the premise that language and communication are facilities utilized to share information between/among human entities. One of the reasons of living is to communicate well (Husain, 2013). Effectiveness of communication is fundamental in creating a relationship among the interactants. That is why Hybels and Weaver II (2004), Brownell (2009), and Summers (2010) argue that effective communication assists an individual to enjoy life in meaningful ways. On that note, one could add that the level of language and the purpose of sharing an idea are some of the denominators of effective communication. To reiterate once more, sharing information enhances strong relationships. That seems the motivation for advertisers to consider permeating the society with good communication resources as a great responsibility that must yield results. So, communication is pivotal in every social behavior (Picard & Pickard, 2017).

To that end, the transmission of messages based on the common knowledge of participants involved has attracted scholars’ interest. Consequently, Velentzas and Bruni (n.d., p. 117) describe communication as an activity of conveying information through the exchange of thoughts, messages by speech, visuals, signals, writing, or any other human behaviors. In other words, this is a sign-mediated interaction between at least two individuals with combinatory, context-specific and content-coherent paradigms (Malá, 2016; Adam & Kalischová, 2017; Diedrich, 2017). The people relating one with another must function in the same level of understanding. Bittner (1985) refers to that platform as a pedestal of linguistic homophily; and Keyton (2011) labels the situation as posing common socio-cultural understanding of the contents involved.

An etymological appreciation reveals the terminology of communication as a Latinized element. That is, communis, which Lunenberg (2010) exemplifies as common. Given that semantic illustration, communication has a goal: it is to disseminate or share a common message through available means (interpersonal, the media, etc.) between one, two or more personalities, or a quantum of target audience (Kapferer, 2012; Şeitan, 2017). With such responsibility, communication, one could attest, is a process of sharing thoughts among individuals. By process, the study refers to a particular entity operating with organized elements. In such case, encoder (sender, writer, speaker), message, medium and decoder (receiver, reader, listener) are facilitators of the communication process (MacInnis, Park & Priester, 2015; European Commission, 2017; Geiser, 2017). Another important device is feedback (Cheney, 2011). Although the matter of feedback is not common in all forms of communication, however, at a stretch, Aristotle (<300 B.C.), Shannon-Weaver (1948), and Osgood and Schramm (1954), Berlo (1960), Jakobson (1960) and Dwight (1978), among others, have charted the channel of communication as occupying: source, encoding process, message, channel, decoding process, received, feedback, and noise (Dominick, 2005); or sender-receiver: message, channel, noise, feedback, and setting (Hybels & Waever II, 2004). Exclusive resources about communication channels are in Griffin (2000). Nevertheless, Eisenberg (2010) articulates that barriers from the sender, medium of communication, receiver, etc. in the communication circle could serve as interference to the smoothness and effectiveness of the message.

Communicativeness of Advertising

Advertising as a form of communication operates in a very wide scope. In some respect, advertising is verbal and non-verbal (Vestergaard & Schroder, 1985, p. 13), public and mass (Hybels & Weaver II, 2004, p. 21), socio-cultural (Dyer, 2005, p. 79-81), and unidirectional (Awonusi, 2007, p. 88) models of communication. The frame of an ad usually contains the text and image. The latter might come in a form of pictures and colors. In that sense, the text relates with the image in relaying or anchoring characteristics (Barthes, 1968; Forceville, 1996; Durant & Lambrou, 2009; Ludwig, 2017). The campaign of advertising is rooted in the mass media, either in the print or electronics. As such, the mass media as a public entity has become, in Dyer’s (2005) point of view, a servant of advertising etiquettes. The basis is that the media helps manufacturers to convert anonymous audience to a market place. Thus, the media benefits immense financial accruement from advertising as well as enjoying harmonious relationships of ads with other contents that make up the media (Harris & Seldon, 1962).

The manipulation experienced in advertising artifacts is not ordinary: it is rather intentional. Hoey (2001, p. 17) constructs the advertising target audience as a set of individuals whose interest is not even in advertising campaigns (also in Ang, 1991). Hoey’s argument seems the impulse that stimulates experts to strategize and venture into the socio-cultural norms of society to reconstruct and sell such materials back to society (Fiske, 1989). This is a tactic to inspire the public to advertising messages. In that regard, advertising exercises operate within the culture of the people for persuasive reasons (Grossberg, Nelson & Triechler, 1993; Willis, 1990). Feedback, operating as the least echelon of the communication process, seems not to enjoy the company of advertising. This is because, most of the time, advertising is a one-way communicative enterprise (Thompson, 2004). Notwithstanding of such feature, advertisers expect the patronization of goods and services as the authentic feedback. Besides, criticisms of the readers-cum-analysts might sometimes serve as feedback. Advertising, crossing the bar of legalistic norms, could also earn the operation another kind of feedback. Outside these unusual feedback curves, the consumption of advertised product as the feedback, can satisfy the yearning of advertisers because manufacturers generate enough cash from the consumption of commodities.

There is a probability that manufacturers are competing for the consumers’ attentions for their products, and that struggle has, perhaps, dictated and determined the nature and content of information in ads of products. The skillful demonstrations of copywriters on texts known as language play (Warren, 1986; Durand, 1987; Crystal, 1998; Roos, 1991; Piller, 1997; Sauer, 1998) are informed by a number of factors at different degrees. Myer (1994) recapitulates the resources in the following terms: careful construct of textual choices, inter-textual interpretations of texts, and generic patterning of ads. Myer also states that ads dictate to readers certain expectations; readers generate multiple meanings from the message; and ads create a common ground of partnership between advertising practitioners and recipients (also in Ewen, 1976; p. 37, 38). These exploitation channels create image for products, companies, advertising professionals, and perhaps, the economy at the expense of consumers.

Theoretical Stance

The picture and wordings are very significant in many advertising plates. The picture, as Forceville (1996) asserts, easily appeals to the eyes of the beholders; whereas the text fortifies the image in order to accomplish further interpretation of the message intended. As some of the textual elements need formal education for proper interpretations, the picture is quite unlikely (Dalamu, 2017a). That claim is exempted in an environment where a pictorial device operates in an unframed posture (Edell & Staelin, 1983; Kroeber-Riel, 1991). Both the literate and otherwise have certain abilities to enjoy the meanings of the picture. Notwithstanding, the main objective of communication in general, and advertising in particular, is to disseminate meaning potential to the public (Hart, Plemmons, Stulz, & Vroman, 2017). Then, it is nice to comment that meaning derivations in ads are lumped into three sets of participants: The first one is the creator of the artwork; the second one is the recipient of the ad; and an analyst is the third personality of the meaning derivative events. It is probable that ambiguity of meanings could occur from time to time. However, it is important that among these interpreters, there should be an equilibrium point in their variegated meaning perceptions. This is the drive that could propel every ad to be simple and easily digested by all the meaning interpretive stakeholders, and particularly the target audience.

Constructing either the producer or the recipient of ads for meaning derivations seems a great task. Then, the interpretation of the analyst could be in the forefront (or a front-burner), considering the fact that interpretations of ads are most time achieved through theoretical applications. The individual could serve as an arbitrator between copywriters and the entire public that consume the ad. It is in that circumstance that the investigation has deployed the concept of ‘below the clause’ from the Hallidayan theoretical school as the interpretative device concerning the grammatical elements performing some functions of the text types. By text types, the study follows what Stubb (1996) describes as “conventional ways of meaning: powerful, goal-oriented language activities, socially recognized types of texts, which form patterns of meaning in social world […] an essential concept in purpose […] for audience” (p. 11). Stubb’s remarkability rests on the assumptions that the assignment given to a text to do determines the way of its construct as well as deployment, and that a user of language is culturally conscious of every text employed for excitement of feelings and imagination of events (Goddard, 2011; Kramsch & Zhu Hua, 2016; Kahraman, 2016; Arslana, 2017).

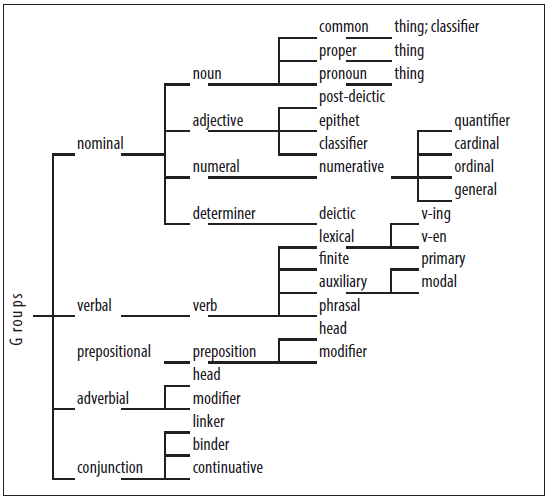

The terminology of ‘below the clause’ points to a partial contribution that a linguistic facility makes in the form of a single structural lane (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2014). That refers that the organs of ‘below the clause’ function in one operation to perform meanings. In a way, Halliday and Matthiessen (2004, pp. 309-310) say that there are logical components from the experiential metafunctional perspective (Madolo, 2016; Dalamu, 2017c). These devices define complex units of a grammatical system in a combination of words of like-manner, built together to produce a meaningful logical relation. This association influences the labeling of the string as a group (Thompson, 2014). Thus, there are about five groups in the system of the English grammar as highlighted: nominal group (NG); verbal group (VG); adverbial group (Adv G); conjunction group (Conj G); and prepositional group (Prep G) (Fontaine, 2013). Figure 1 below illustrates the system of groups in English.

Figure 1 above shows that the nominal group is an embodiment of noun, adjective, numeral, and determiner. In this case, noun operates in three different fields of common noun, proper noun, and pronoun. Such operations position the nominal group elements as “thing” or “classifier” (Bloor & Bloor, 2013). Adjective, as a qualifier, functions within the nominal group elements in the form of post-deictic epithet or classifier. This is because each of the operational facilities provides more information about an element of a clause (Eggins, 2004). Both numeral and determiner, which function as either numerative or deictic, are also modifiers in the sphere of the nominal group.

Verbs and prepositions function as verbal group. Although, the study separates the prepositional group from the verbal group simply because the clause has the capacity to accommodate the preposition in the domains of linguistic structures, relating to verb as modifiers and to adjunct as circumstances and as interpersonal tools (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004). The verb can function as finite, auxiliary, or lexical items of the clause (Matthiessen, 1996; Dalamu, 2017b). Similar to the verbal group is the adverbial one, which has adverbs and conjunction functioning in its domain. The adverbs are realized through the head and modifier. However, conjunctions operate either as linker, binder or continuative. Most of conjunctions are markers of the clause (Thompson, 2004; Martin & Rose, 2013). In all, observations show that the taxonomy of the group devices is not static in any way. The basis is that some of the group elements perform intersectional relationships in the clause. A worthy example is the NG competing in the domains of Adv G and Prep G respectively.

Research Questions

How do advertising communicators utilize disjunctive constructs to achieve sensitization in the public glare? Have the systemic meanings inspired the target audience in certain ways? Or can an investigator remark that the lexemic group facilities are just ordinary strategies of differentiating one brand from another in the competitive market parlance? These are questions that the research has seemingly addressed to reveal the goal of advertising. These questions are of great importance on the ground that one is actually amazed so many times about the rationales behind the constructions of disjunctive grammar as texts in advertising plates.

Methodology

Participants

There are many ads on disjunctive structures in the print media. One can observe their variants in billboards, magazines, newspapers, etc. across Nigeria. However, the author chose billboards and the newspaper as sites for collecting ads. Reasons of appropriateness and avoidance of a quantum of ads, leading to confusion motivated the researcher to limit ads’ collection exercises to billboards and the newspaper (The Punch) between July 2016 and March 2017. Regarding billboards, Lagos and Ibadan (of Lagos and Oyo States) were the domains where the ads were obtained. The basis is that Ibadan is the largest city in Nigeria (Fourchard, 2004; Balogun, 2015; Azeez, Adeleye & Olayiwola, 2016), while Lagos operates as the commercial nerve center of the nation’s economy (Oduwaye, 2007; Osoba, 2012). These two cities seem the target of publicity practitioners’ campaign spheres. Bonke, a lady of 35 years, and the researcher traveled around Lagos and Ibadan in a motor vehicle to observe and harvest relevant ads to the investigation. The ‘merry-go-round’ gave us the opportunity to view many ads, and to ensure the selection of appropriate ones, based on structural development of their disjunctive forms. This similar condition was considered for the newspaper ads’ collection strategy.

Research Design

At this point in time, the combination of 36 ads from both billboards and The Punch reflected the population. The analysis adopted a stratified sampling procedure (Keyton, 2006; Charmaz, 2014) by dividing 36 ads collected from the field into three sub-groups (Gentles, Charles, Ploeg & McKibbon, 2015). This method permitted the author to select a relatively small number of ads (12 ads) from a defined advertising framework (36 ads), to serve as a simple-based subject. Thus, the procedure has augmented the speed of analysis (Nwabueze, 2009 Lichtman, 2013; Leedy & Ormrod, 2014; De Vaus, 2014). During the data collection process, observations indicated that some ads appeared in homogenous forms, while some advertising devices were haphazardly organized. These unavoidable situations compelled the researcher to select 12 ads, well organized, as the right choices. The decision also enhanced analysis’ aptness, suitability, and assisted in avoiding repetition of analysis of a sort. Twelve ads, more relevant to the study in terms of the disjunctive configuration of textual constructs, were analyzed to serve as the factual representation of 36 ads.

Instruments

A Samsung WB50F camera was used to capture the ads in various billboards and pages of The Punch newspaper; its large reading audience in Nigeria informed the choice of capturing ads from its pages, and not any other avenue. I also have ample access to the newspaper. Moreover, the selection of ads from signposts across two cities of Lagos and Ibadan, as well as The Punch newspaper provided a large room for comparing one ad with another to make a reasonable decision on the appropriate ads to be investigated. The population of the ads was 36 frames. The selected pieces offered the author accessibility to varieties of ads propagated in the media with disjunctive texts. As earlier stated, that exposition influenced the suitable choice of ads for analysis.

Procedures

The 36 ads were grouped into three different parts, in terms of their textual disjunctive constituents, discourse patterns, and semantic implications. The organization of the disjunctive blueprint was also considered a vital factor in the grouping and selection of the data. Nonetheless, one-third of the population was selected for the analysis, as a calculated sample. To reiterate, the choice of one-third facilitated and fast-tracked easy analysis, informing correct decision making on the features of the texts. The limitation of the population to 12 ads was to avoid unforeseen difficulties that might create unnecessary burden on the investigation. The number limitation relied also on the matter of available space on the journal. It was very easy to hire Bonke to convey me round Lagos and Ibadan cities in search of ads with disjunctive texts for we have been ‘partners in progress’ in harvesting ads. The choice of the lady rested on her adequate knowledge of strategic places where crucial advertising events are communicated to readers in Lagos and Ibadan cities.

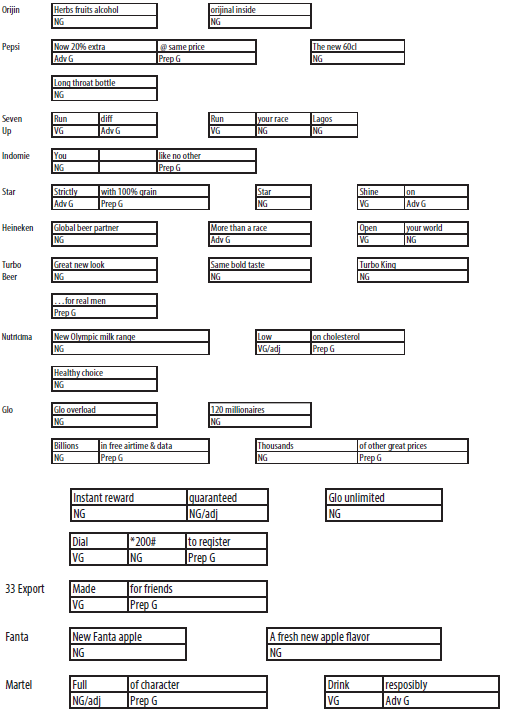

Twelve ads of Orijin ® , Star ® , Heineken ® , Indomie® , etc. were utilized for analysis. Halliday’s ‘below the clause’, illustrating the groups, as discussed in Halliday and Mat thiessen (2014), functioned as the processor of the disjunctive constructs, as shown in Figure 2. Nesting (//), as a tradition in Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL), was used to mark the strength of each disjunctive structure. Following Bryman (2006; 2012), Creswell and Plano (2011). Miles, Huberman, and Saldaña (2014), and Patton (2015), the study employed a combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches to evaluate the ads. As complementary concepts (Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2009).), the qualitative procedure dominated the processing of texts into analytical parts (Creswell, 2013; Corbin & Strauss, 2015); while the quantitative method allowed statistical instruments to compute the values of textual communicative devices (Lisotteli, 2010; Maxwell, 2013). Thus, Table 1 has helped to translate the analysis of Figure 3 to account-able forms for proper calibration of the recurrence of the groups in ‘below the clause.’ The study has also used the bar chart (Berg, & Howard, 2012; Dalamu, 2018) in Figure 3 to demonstrate the frequency of VG, NG, Adv G, Prep G, and Conj G, as advertisers have deployed the terminologies for persuasion. The discussion expounds the disjunctive facilities in relation to the theoretical sequence of the study for both structural and semantic relationships. For visual communication, the investigation embeds the advertising plates under consideration in the discussion segment. The symbol, ‘®’ represents a registered firm or a brand, while ‘₦’ indicates the symbol of the Nigerian currency.

Data Presentation

Orijinal ®: //Herbs fruits alcohol// Orijinal inside//

Pepsi ®: //Now 20% extra @ same price// The new 60cl// Long throat bottle//

Seven Up: //Run diff// Run your race, Lagos//

Indomie ®: //You like no other//

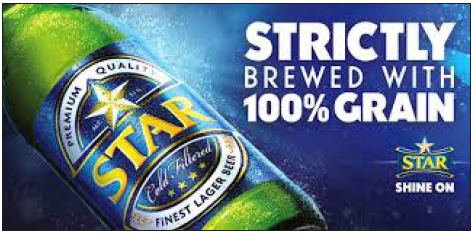

Star ®: //Strictly with 100% grain// Star// Shine on//

Heineken ®: //Global beer partner// More than a race// Heineken// Open your world//

Turbo Beer ®: //Great new look// Same bold taste// Turbo king// …for real men//

Nutricima ®: //New look Olympic milk range// Low on cholesterol// Healthy choice//

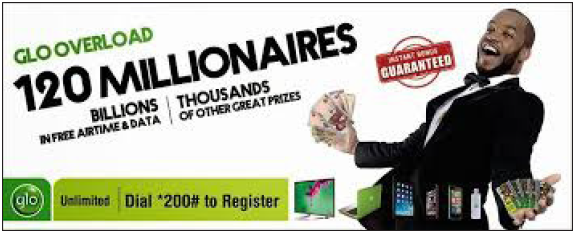

Glo®: //Glo overload// 120 millionaires// Billions in free airtime & data// Thousands of other great prices// Instant reward guaranteed// Glo unlimited// Dial *200# to register//

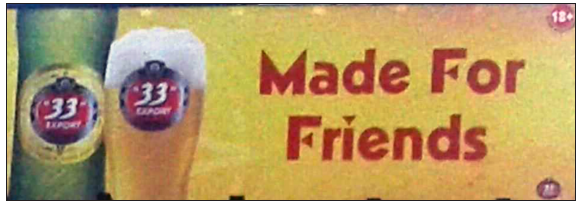

33 Export ®: //Made for friends//

Fanta ®: //New Fanta apple// A fresh new apple flavor//

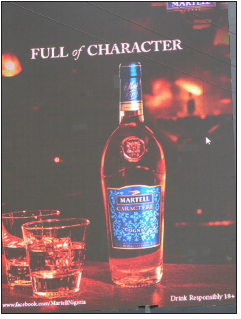

Martell ®: //Full of character// Drink responsibly//

Results

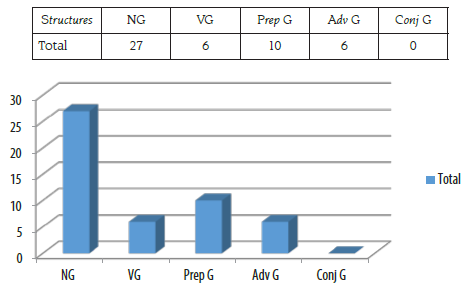

Table 1 indicates the recurrence of the groups in the ads. The table has been translated to a graph in Figure 3, as an illustration of the frequency in terms of heights in consonance with the insights of Geiszinger (2001), and Dalamu (2017b). The bar chart shows clearly the visual appearances of the groups’ deployment.

Table 1 Group recurrence

| Products | NG | VG | Prep G | Adv G | Conj G |

| Orijin | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pepsi | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Seven Up | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Indomie | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Star | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Heineken | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Turbo King | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Nutricima | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Glo | 8 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 33 Export | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Fanta | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Martel | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

Source: prepared by the author.

NG in Table 1, observations show, occupies the scenes in the entire messages that support the products, except in 33 Export ® that the record is nullity. The other scores are in Prep G, VG and Adv G. Conj G records no point at all. Then, the table exhibits the familiarization of advertising experts with NG as the most important punctuated tool of influence, perhaps, in persuasive procedures. Figure 3 below also portrays a similar ac count but in the bar chart illustration.

Figure 3 demonstrates that the NG recurs in the chart twenty-seven times. That re currence refers that the NG occupies the most prominent part of the message functional domains of ads. Prep G operates around ten times to claim a second position. The graph expounds further with both VG and Adv G recurring six times respectively; whereas Conj G has no value. The appearance of the values in Figure 3, once again, positions NG as the dominance facility of inducement. By implication, advertising professionals enjoy convincing the target audience with the elements of NG such as nouns and devices surrounding the terminology as modifiers and qualifiers. Obviously, the Prep G is in the second position as a persuading facility. One needs not to be amazed of this conduct because apart from the preposition that serves as the marker of the Prep G; it seems NG occupies the remaining part as the modifier, as earlier shown in Figure 1. Although VG and Adv G are in the third place, advertising experts utilize the concepts for excitement as well. The disjunctive gram mar of ads, one could suggest, according to the reading of Figure 3, operates meaningfully, more in NG and slightly in Prep G, in order to inspire consumers to consumption. Signifi cantly, publicists appear to have seen both NG and Prep G as sure constituents of coaxing readers. This is because the textual structures are consistent communicating components of fascinating the target audience. In addition, the analysis in Figure 2, transformed to the group frequency in Figure 3, pinpoints the deployment of NG and Prep G, as constitutive strategies of convincing readers to patronize goods and services.

Discussion

The study’s centerpiece, the author could reiterate, is the analysis of the disjunctive gram mar that the advertisers utilize to meaningfully influence the public in order to patronize the advertised commodities. To that end, the guidelines of the explanations on the disjunctive pieces appreciate structural details as linguistic devices based, on Bloor and Bloor (2013) exemplification in consonance with Halliday and Matthiessen’s (2004) thoughts on below the clause. It is on the same path that the semantic implications of the linguistic devices are appraised. To excite readers with segmented choices of the advertising gurus, the study goes ahead to suggest some elliptical elements that seem to produce the fragmented clauses on the advertising plates.

It is very significant to state that the word Orijin ® is a lexical borrowing (Benő, 2017) displaying an intercultural relationship (Gill, 2016) between the English and Yorùbá lexeme. The advertising expert exhibits such association with the replacement of the English grapheme ‘g’ with the Yoruba ‘j’. There are two linguistic organs separately deployed in Plate 1 to persuade consumers regarding the consumption of Orijin. These are: herbs fruits alcohol and original inside. Herbs, fruits, and alcohol are three nominal elements that are supposed to receive commas to distinguish each of the nouns. But the textual stylist just leaves them as a single string qualifying one another. As herbs fruits alcohol are not qualifiers, in normal writing style, they ought to appear as herbs, fruits, and alcohol as elements distinctively functioning as Thing in their capacities. The second structure, orijinal inside is a NG that accommodates orijinal as Thing with inside as Epithet that serves as post-modifier. The two communicative organs seemed as fragmented structures from the clause Herbs, fruits, and alcohol are (i) the original content that is (ii) inside the Orijin container.

Following the suggested clause, herbs point consumers to green leafy plant in the Orijin that serves as flavor to season the beverage. Herbs also refer to roots of some plants with medicinal substance beneficial to the well-being of consumers. The mentioning of fruits indicates that the edible produce of plant that people commonly eat without any agro-allied preparation are parts of the contents of Orijin. Stating that alcohol contribut ing to the additive elements is to campaign that Orijin is neither a drug nor a fruit juice. The product is rather a mixture of herbs, fruits and chemical organic compound, in which its excesses intoxicate the brain. That means Orijin, in addition to other things, contains hydroxyl functional group. This is a sort of slight warning to consumers in order to be very careful of the quantity of Orijin to be taken at a time. Although, the warning is not so much striking, consumers who are wise enough could easily observe to heed the instruction in order to abstain from excess consumption, as presented in Plate 1. Those who are not ‘intelligent’ might fall preys and consume as much Orijin as possible until such individuals are drunk. So, the mentioning of alcohol heralds a great warning to the public.

The Pepsi ® ad begins with an elliptical structure that contains an Adv G, Now 20% extra and a Prep G, @same price. The construct of Now 20% extra has Now as the marker with 20% extra as NG. Now is adverbial of time that marks the inducing statement. A keen examination of NG shows that two linguistic elements of 20% as modifier and extra as Head. Being facilities of NG, 20% is Numerative in a quantitative form providing appropri ate information to readers about what the extra, Thing, looks like. @same price is a Prep G, as demonstrated in Plate 2. As Now serves as a marker to the Adv G of Now 20% extra, so is @ in the Prep G of @same price. In that case, apart from the marker differentiation both Adv G and Prep G have NGs as modifiers. As a result, same price modifies @. It is in a similar vein that same pre-modifies price. Same is an adjective in form of Epithet while price is a noun operating as Thing.

The new 60cl is a NG that is also fragmented from the front and back. Before discussing the fragmentation exercise, it is significant to say that the NG contains two devices for modification. That is, The new and 60cl as Head. The, the definite article, as commonly called, is labeled as Deictic in systemic linguistics. The basis of that is that The is a determiner that points to an entity as a derivative of a Greek lexicon (Bloor & Bloor, 2004, p. 140). New as Epithet is another linguistic device that pre-modifies 60cl. The employment of new is a common phenomenon in the advertising business (Geis, 1982, Sells & Gonzalez, 2003). The chopped up structure, Long throat bottle, also operates at the domain of NG unlike earlier discussed NGs. Long throat bottle has bottle as Thing with two different elements of Long and throat supporting the noun head element as Classifiers to offer readers proper information about the bottle in reference. The characterization of the bottle becomes necessary as a strategy to persuade consumers about the distinction of the bottle. Nonetheless, the shape of the bottle, to the analyst, has little or nothing to add to the content of Pepsi inside the bottle. The throat reference seems a marketing ‘propaganda’, aimed to influence behaviors of the target audience.

The study could collapse the three punctuated structures into two, in order to yield necessary clauses. These are: Now, [Pepsi contains] 20% extra [content] at the same price; and [This is the] new 60cl [of Pepsi in the] long throat bottle. Four important pieces of information are significant in the clauses. These are: quantity of content; price relevance; newness of the product, and bottle identification. 20% and 60cl promote the volume of the beverage, which do not in any way heighten the price. The increase in volume without a price review can influence readers to consume more of Pepsi than any other competing product of its degree in the beverage market. It seems to the author that some people love to seemingly patronize cheap things in the world. Perhaps, that is culturally human. The bottle identifi cation is a distinction of the later bottle of Pepsi from the former. This is in the sense that it is quite possible to use the same appearance of bottle for the new volume. The only remarkable thing is that the new bottle will be bigger than the old one. The introduction of the lexeme, new, captures all other persuasive devices. New facilitates the message in all spheres. The advertising practitioner lumps the newness persuasive philosophy to 20% extra, same price, 60cl, and long throat. One could pinpoint, as indicated in the textual constructs, that the advertiser fascinates the readers with external features of Pepsi bottle and not the original content inside (as a loan-statement from the ad of Orijin).

The Seven Up ® ad deploys two clauses, although, one of them is punctuated to sensitize the target audience. Run diff is a fragmented structure; whereas Run your race, Lagos is not deleted in any form. However, both clauses are imperatives functioning as commands. The imperative is one of the commonest advertising language, through which consumers are forcefully directed on what to do (Leech, 1966; Hermeren, 1999; Kalmane, 2012). Run diff is a clause with an elliptical diff. Diff is advertiser’s model of portraying differently. One could quickly assert that the application of diff seems to reference a drinking situation. Diff is connected to the way that a consumer drinks Seven Up. In other words, it is an appreciation of the weaseling sound observed when a consumer enjoys the beverage. Run and diff are products of VG and Adv G despite that each word falls into different word classes and groups. The terminology of ‘group’ does not necessarily mean that two or more words operating together as a string. A single word has the capacity to operate alone as a ‘group’ in a clause (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2014; Thompson, 2014). In the Interpersonal Metafunction, Run, as operating in this ad is Predicator. Diff as a clipping form of differently is adverbial that serves as a circumstantial entity, indicating the manner in which consum ers should organize themselves. Diff states the quality of one’s action.

The second aspect is Run your race, Lagos, which is an embodiment of VG and NGs. Run is a common denominator of the two clauses. Your race is an NG with your functioning as possessive pronoun in the domain of Deictic. Your indicates ownership. Race is the Head of the NG. As an element performing experiential function, race specifies a particular class of an item. Lagos is the noun, representing the NG in the manner that run denotes the VG. Linking the status of Lagos to the concept of Multiple Theme, Lagos is vocative in the sphere of Textual Theme (Thompson, 2004, p. 159). To derive a single semantic implication for Run diff and Run your race, Lagos, it is suggestive for a single reconstructed clause to suffice by eliminating one of the run components. That is, Lagos, run your race differently. By that clause, the analyst could comment that the advertiser enjoins participants of the Lagos tournament of long distance race to distinguish themselves from the others, perhaps, from other cities in the nation.

The message points readers to the fact that there had been other long distance race(s) in other cities in Nigeria. Lagos athletes, to the advertiser, are people of special qualities, thus, the call to be set apart. Actually, the advertiser expects a different experience from what the race usually looks like. Of a note, however, it appears that the primary concern of the ad is the selling of Seven Up, and not the race per se. This is remarked with the shortened lexicon, diff, which is a replica of the renowned cliché of Seven Up, that is, ‘the difference is clear.’ It is out of the core value/belief that Seven Up cherishes that the copywriter has extracted diff as the sensitizing edifice. Diff is supported with a bottle of Seven Up in the frame demonstrated in Plate 3.

The Indomie ® ad has You like no other as the accompanying text. The text contains You as NG and like no other as Prep G. You is a pronoun in the second person cadre and at the same time the Head of the NG. Like no other is Prep G with the marker, like, playing the role of Head supported with no other which is also NG. Then, no signals emphatic agreement of negativity. In that case, no is an element facilitating negative polarity. No as a pre-modifier negativizes anything that loves to compete with the other, which serves as the Head of the NG. The supposed clause is declarative which could appear as You [are] like no other. By implication, the Finite, are, has been deleted. The point is that the advertiser seems to disregard finite elements as carriers of information in advertising exercises. The claim is remarkable as virtually all the ads of the study do not have Finite as a message propaga tor. The copywriter creates a very strong impression with this text by making a reference to readers and not to the advertised product. By projecting a campaign thought toward consumers, it is pertinent to say that consumers are made more relevant than Indomie advertised in packs. You like no other classifies an individual consumer as a celebrated personality in the marketing competitive curve, which all advertisers ‘run differently’, like a ‘race’ (as a loan-construct from the Seven Up catch phrase).

There are three textual portions of text in the Star ® ad in Plate 5. These are: Strictly with 100% grain; Star and Shine on. Apart from Shine on that is a complete clause, other segmented units are chopped up. For instance, [Star is brewed] seems to be deleted from the first structure and This is removed from the second structure. Strictly with 100% grain accommodates Adv G as Strictly and Prep G as with 100% grain. Strictly, as deployed in Plate 5, constructs a bar of restriction to the raw materials of the Star lager beer. Prep G, with 100% grain, has with as the Head and 100% grain as the NG. 100% is the Numerative that pre-modifies grain, which signals the Head. The full stretch of the clause is [Star is brewed] strictly with 100% grain.

The second portion is Star the NG, which is the name of the beer. The pointer, This, seems to have been deleted from the clause to leave Star behind. Therefore, the clause is [This is] Star. The third part is Shine on. The grammatical structure contains both VG and Adv G, in which the group shares the lexicon one by one respectively. Shine is verbalized, while on is an adverb indicating continuousness. The excitement of the text takes two shapes. Strictly with 100% grain illustrates the feature of the content of Star - a rigorous content of cereals, while Shine on dictates to the audience to excel in brightness. In other words, drinking of Star, in the opinion of the advertiser, will illuminate consumer’s life as a reflection of a brighter life that the message demands from the individual drinker.

The Heineken ® ad contains text in three distinct dimensions. These are Global beer partner, more than a race, and Open your world. In a similar fashion to the conditions of the structures obtainable in the Star text, Heineken text has Open your world as an imperative issuing a command to influence recipients (Eggins, 2004). Global beer partner is NG, and More than a race is Adv G. Both Global and beer are Classifiers that pre-modify partner the NG Head. The advertiser associates Heineken with global partner to create a sort of internationality for the beer. The creation of partnership has influenced the writer to suggest Heineken is associated with Global beer partner as the full-fledged indicative clause.

More than a race is a sport-like statement. The linguistic device more than - an adverbial - is pointing to an extent of happiness. A race, another NG in the domain of Adv G, is a reference of a sporting action. A is an indefinite article in the field of determiner, whereas race is a noun. The real clause could be read as [It is] more than a race. The last unit, Open your world is a combination of Open and your world, NG. Open is a lexical item and a process in the meaning potential of Ideational Metafunction as a reference to accessibility. Nevertheless, its application in the ad is metaphorical. This is on the ground that Open refers to the removal of the Heineken beer as a preparation for its consumption. Your is possessive and world is Head. On that note, one could assert that Open your world creates a connection of internationalization between Heineken and consumers. In sum, the ad utilizes globalization as the interface between consumers and Heineken, in terms of partnership and sporting activities, that Heineken is inclined with to inspire the public.

The text of Turbo King ® is divided into four units of Great new look, NG; Same bold taste, NG; Turbo King, NG; and for real men, Prep G. In the Great new look string, Great is Classifier, new is Epithet and look is Thing. It means that both Great and new pre-modify look. In the next NG, Same is Classifier as well as bold where taste operates as Head of the group. The least NG accommodates Turbo as Classifier and King as Head. For is the Head that also marked the Prep G accompanied with another NG. Owing to the recurrence experience in the discussion, one could reiterate that advertising popularizes NG as the model of meaning making in the texts. Real men as the modifier of Prep G has real as Classifier and men as the Head. The reconstruction of the fragmented organs could appear thus: [Turbo has a] great new look; [It is the] same bold taste; [This is] Turbo King; and [Turbo King is] for real Men.

Most salient facility in the constructs is bold taste. In that regard, one could ask whether a taste can be bold? If the answer is not in affirmative, then, the deployment of bold to ‘collocate’ taste is seemingly a wrong linguistic application; such misuse is erratic. That is why Okoro (2008) appropriates such linguistic behavior as erroneous application of collocation in English. However, the advertiser cannot tender any apology for the advertising industry in general operates under the guise of poetic license (Horn, 2010; Xhignesse, 2016) - a tactical communicative approach to side attraction. The entire text of Plate 7 inspires readers through three things, exhibited as the ‘physique’ of the bottle, uniqueness of the taste and the expected consumer of Turbo King.

By real men, the message tries as much as possible to inform readers that ‘expectations are very high.’ The copywriter attempts to define a standard for readers, by nullifying ‘artificial’, ‘fictitious’, and ‘counterfeit’ consumers. Turbo King is brewed out of genuine ness, as the frame reports, for strong and eminent people of high integrity. In that sense, the advertiser seeks devotees to the consumption of the beer. Such individuals, in the perspective of the copywriter, must be fond of this kind of beer in an accelerated manner.

Except in the second segment of the Nutricima ® ad, all the other disjunctive structures are NGs. The NGs are: New Olympic milk range; and healthy choice. The Prep G is low on cholesterol. New is Epithet, Olympic is Classifier. Milk is Head and range is Epithet. As new modifies Olympic milk is the same way that Olympic modifies milk. As such, range is a qualifier of Olympic milk in the post-modification position. So, the Head, milk, is encircled with pre- and post-modifiers. The next unit is low on cholesterol with low as an adjective in the class of NG and on cholesterol, which is Prep G. Besides on operating as the marker of the Prep G, cholesterol is a noun functioning in the sphere of NG. Healthy choice is NG which accommodates healthy as Classifier and choice as the Head. Following the discussion’s guidelines, [Nutricima is the] new Olympic milk range; [It contains] low cholesterol; and [This is the] healthy choice are the suggested clauses.

The inclination of the ad is in the fields of sporting activities and health matters. Perhaps, the reason for the dual focus is that many Nigerians enjoy sporting actions most especially the Olympic Games. One could also add that hardly can someone, even outside Nigeria handles health issues with levity. It is foresighted for the advertisers to lure consumers to the criticality of health to propagate the persuasive campaigns. Most people might understand that cholesterolmania, among others, is defective to the blood stream/flow for the ailment has the tendency to block the heart of an individual, to make the human system malfunction (CDC, nd; FDA, nd). The defectability might quickly lead to death.

The text of Glo ® ad has seven fragmented structures within the distribution of VG, NG, Prep G. NGs are Glo overload and 120 millionaires, functioning as the first two units. Glo overload appears as a compound device of the Head. Overload is an excessive offer that the Glo telecommunications firm has made available for subscribers. 120 is a numeral utilized as an indicator of the number of people that will become affluent in no time. The lexeme is a pre-modifier of the Head, millionaires. Billions in free airtime & data had Billions as the NG, and in free airtime & data representing Prep G. The preposition, in, is the marker of the group with the modifier free airtime & data operating again as NG. Free is the Classifier modifying airtime & data altogether.

The fourth segment contains NG, thousands and of other great prices as Prep G. Nonetheless, of, as a preposition, is the pointer of the group with the support of the NG, other great prices. Other is Epithet while great is Classifier, providing more information about the nominal devices of prices. The fifth and sixth units are NGs with different modification structures. Although. Glo Unlimited is a compound element of nominal clusters because the product is a package; instant reward guaranteed is an endorsement, offering an approval to the Glo promotion. Reward is the Head, instant is Classifier, whereas guaranteed is an adjective post-modifying reward. The qualifier, guaranteed, instills confidence on subscribers about the authenticity of the sales promotion. The employment of instant exhibits the immediate effect of the gains of those who participate in the events.

The seventh segment is an imperative clause Dial *200# to register directing the public to the channel of consumption which is systematically tagged as register. Dial is a NG, while *200# is Numerative in the NG, and to register is Prep G with to as the marker and register as a lexical element. This formation of the Prep G/Phrase influences Halliday and Matthiessen (2004) to claim that prepositional facilities, sometimes, operate as minor verbs (p. 359-360). The study has deduced four declaratives and one imperative from the seven punctuated units. These are: Glo overload [will produce] 120 millionaires; [There are] billions [available] in free airtime & data [along with] thousands of other great prizes; Instant reward [is] guaranteed; [This is] Glo Unlimited; and Dial *200# to register [for the promotion].

The textual density of text in Plate 9 shows the extent that advertisers could go to convince ‘recalcitrant’ audience. The sensitization strategy rests on monetary gifts to subscribers. The question is: Is it possible for the Glo operator to freely release such ac claimed/campaigned amount of monetary values to subscribers as gifts? Further research on promotion could attest to the claim of Glo and perhaps other institutions that campaign such messages.

The combination of made as VG, and for friends as Prep G produce made for friends in the plate of 33 Export ®. Made is a lexical verb functioning as Predicator. It is the chopped-up elements that one could say that make the lexicon, made, to appear as if it is a past tense. For is the Head of Prep G signaling friends as a nominal facility. Although friends is a single lexeme, the linguistic unit is at the same time operating as the NG, in the organ. The clause could be suggested as [33 Export is] made for friends. The clause infers that the con sumption of 33 Export is not meant for an individual drinker. 33 Export must be consumed among friends, and by extension in the congregation of many people. This opinion of the advertiser is perhaps referring to a sort of sharing formula for the beer among friends. The sharing, no doubt, might excite friends to buy more 33 Export at a go in occasions of ne gotiating sociability. This is on the ground that the sharing behavior could influence even those who are reluctant to patronize and drink the alcoholic drink. In addition to that, the sharing could block the chances of other beers in the market to intrude into the midst of friends that consume the beer. At the long run, more 33 Export beer will be consumed, apprehending the ad’s raison d’être.

There are two NGs in the segmented structures of the Fanta ® ad. The first is New Fanta apple; and the second is A fresh new apple flavor. New is an Epithet, Fanta is a Classifier, and apple is the Head of the NG. The second NG contains clustering elements of Deictic, A; Classifier, fresh; Epithet, new; Classifier, apple; and Head, flavor. A fresh new apple as well as new Fanta are pre-modifiers of both flavor and apple in their respective NGs. One could suggest the real clause as [This is a] new Fanta apple [with] a fresh new apple flavor. The winning feature of the construct is the additive of apple flavor. The advertiser utilizes the freshness of the flavor to assure consumers of a different taste and aroma of the content of Fanta.

The Martell ® ad has two texts. One is fragmented, that is, Full of character, and the other is an imperative clause, Drink responsibly. Full as an adjective in the field of NG and of character is Prep G. The Prep G has of as the marker while character is the nominal facility, modifying the marker. In a full stretch, the clause is [Martell is] full of character. That orientation personifies Martell as a human entity with certain behavioral attitudes. Drink responsibly sounds a note of warnings to readers not to consumer excess content of Martell. Unlike the ad of Orijin in Plate 1 that indicates alcohol as part of the content, Martell does not. The alcohol content is hidden whereas a warning has been wisely issued to consumers on immoderate consumption. The advice presents the Martell’s producer as a very responsible firm that cares about people’s welfare as well as the quality of the advertised product. Those who are careful might obey the instruction, otherwise gluttonous or overindulgent consumption of Martell could intoxicate them and a probable harm might occur, being the counsel of the advertiser. Besides that, Drink responsibly is a way of cautioning recipients and satisfying government agencies. As a matter of fact, the clause could shield the firm against any litigation against Martell in case someone somewhere is affected by extreme or overgenerous consumption of the alcohol. The features of the content of Martell are left open for consumers to guess the resources that are inside the bottle. Therefore, Full of character puts recipients in suspense of what Martell is in a real sense.

Conclusion

The advertising industry has proven oftentimes that derivations of meaning are not only residing in complete structure of clauses of the imperative, declarative and interrogative. Disjunctive structures as considered in this study offer ‘adequate’ meanings to readers as well. If the claim is questionable, the behavior of advertisers toward the propagation of advertising texts in the spheres of disjunctive segments would have changed over the years. Thus, the study exhibits the utilization of grammatical groups as facilities of persuasion in various ads analyzed. Of all the groups, the nominal group (NG) is the most deployed for excitement, because NG names and concretizes social entities.

Observations point out that disjunctive constructs are a form of strategies organized to convince readers of ads. The advertisers demonstrate this by projecting some of the textual structures in large forms. The enlargement permitted recipients to easily identify the core message of the disjunctive structures. The relatively great sizes, such as Herbs fruits alcohol in Plate 1, Long throat bottle in Plate 2, Strictly … 100% grain in Plate 5, 120 millionaires in Plate 9, and Full … character in Plate 12, emphasize the area of concern of the pieces of information. The deployment of disjunctive components, differentiating one construct from another, is quite deliberate attempts to sway and dominate thoughts of readers. Advertisers further exhibits intentional persuasive behaviors, for instance in Plate 3, where two imperative clauses inform readers about an event. The first is Run diff; the second is Run your race, Lagos. Nevertheless, Run diff, a combination of VG and NG, has a large font; whereas Run your race, Lagos also constitutes VG and NG structures. By implication, the advertiser places special weight on Run diff, making the command a prominent message to viewers.

There are no doubts that advertisers utilize disjunctive structures as systemic devices of producing certain meaning potential. From the analysis, giving credence to NG, NG accommodates the three segments. These are Pre-modifier + Head + Post-modifier, as observed in the ads. Now 20% extra in Plate 2 shows Now as Adverbial, 20% as Numerative (Pre-modifiers), and extra as NG Head; Global beer partner in Plate 6 marks Global + beer as Classifiers modifying partner the NG; Great new look in Plate 7 demonstrates Great as Classifier, new is Epithet, pre-modifying look, the Head; and A fresh new apple flavor in Plate 11 illustrates A as Deictic, fresh as Classifier, new as Epithet, apple as Classifier, and flavor as the NG Head. The manifestation of modifiers and qualifiers in most of the disjunctive grammatical constructs of the ads is a signal to advertisers’ deliberate styles; where publicists employ not just nominal words, but that noun Heads receive additional information. Advertisers seem to modify the Heads as a form of elaborations. Such detail makes advertising nar ratives more sophisticated.

Structures such as Long throat bottle, Same bold taste, New Olympic milk range, and A fresh new apple flavor are experienced in the ads with meaning potential. Although they are minor, verbal groups (VG) such as Shine on and Open your world; prepositional groups (Prep G) such as like no other and to register; and adverbial groups (Adv G) such as diff and responsibly are also employed for conviction. Meaning derivatives reside in disjunctive grammar, despite the fact that such meanings might be ambiguous sometimes.

Besides the linguistic devices, the study reveals that elements in relation to the features of the commodities, external appearance of the product’s container, and benefits and values that consumers will derive from the products, facilitate the advertising campaigns. In addition, advertisers associate with sporting activities, monetary rewards and international bodies as useful tools of inspiration in the persuasive principles. Sometimes, the texts also exalt consumers in the area of health to lure individuals to consumption. Linking ads to health matters is laudable because of its educative status. It is important for agencies to appreciate the move on health issues, and to further ensure that things propagated about health are not discarded with a wave of the hand. Nonetheless, it is very imperative for government agencies to verify the advertisers’ claims on health matters as either being genuine or counterfeit. If such claims are sacrosanct, government agencies need to persuade advertisers, as a matter of responsibility, to enlighten the public more about health hazards and health benefits of advertised products. The creation of such awareness could sensitize readers on decisions on goods and services to patronize and products that are not to buy and to extremely avoid. Such campaign might invariably lead to long life and prosperity of readers of ads. It is also possible that the disclosure of the contents of commodities (e. g. food items) might inspire many people to be interested in reading advertising campaigns. Semiotic manifestations, as well as a comparison of textual structures of Nigerian and Colombian advertising spaces, are considerable domains that could attract further studies.

Acknowledgements

The author is very much grateful to Prof. ‘Tunde Opeibi, Chair, Digital Humanities Research Unit, Faculty of Arts, University of Lagos, and Mr. Basiru Dalamu of Bashy Motors, Ikotun Lagos for providing funding for the harvesting of the advertisements within and outside Lagos Metropolis. Besides, one also appreciates useful suggestions that he offered con cerning both the trend of the analysis and the discussions thereafter. Worthy of note is the contribution of Mrs. Bonke, who persistently drove the author around the nooks and crannies of Lagos as well as the outskirt of the city. That endeavor gave the author the latitude to obtain relevant advertisements for the study.