Introduction

Citizen interaction with large sets of information and media content has increased nowadays as the traditional industry and new players nurture the media and information landscapes with contents of different types and diverse production methods (curation and validation). The inclusion of new information providers, user-generated content, public (government) information, among others, opens the range of delivered and consumed information in terms of its scope and quality (Orozco, 1997). In this context, digital citizens -as can be regarded- are exposed to several sources of information, media, and cultural products and. They, therefore, are also exposed to the opportunities and risks associated to misinformation, fake news, low-quality content, and other problems generated by the lack of media competence.

In response to this increasingly mediated and challenging scenario, international organizations, researchers, scholars and some governments have seen media and information literacy (MIL) as a way to foster media awareness and empower citizens towards information inputs (Durán-Becerra & Tejedor-Calvo, 2017; Petranová, Hossová, & Velický, 2017; Leaning, 2017, pp. 117-127; Literat, 2014). In this regard, media competence, as fostered by MIL, implies that citizens ought to gain the capacity to interact, understand, use, transform and create information in an advanced, critical and transparent way, a capability not granted by the mere acquisition of technical skills or the use of the latest information and communication technologies (Giraldo-Luque, Villegas-Simón, & Durán-Becerra, 2017; Lopes, Costa, Araujo, & Ávila, 2018).

Media and information literacy (MIL) is a concept based on many notions and trends, an initiative of Unesco (2008, 2011a; 2011b, 2013) that aims to create a holistic understanding with a broad theoretical proposition grounded in current trends from both fields (media and information). The last ten years have been of crucial importance for Unesco’s MIL theoretical positioning and concept promotion, as well as for defining related competences. The objective of this organization is to converge in a single discipline the different approaches to MIL (Lau & Grizzle, 2020). This paper therefore aims to identify the conceptualization of MIL in the still-incipient literature produced around this merged concept, where two objectives of similar competences become related in their inherent skills and minor different processes.

The concept of MIL refers to both processes of understanding and use of media (media and information) as well as the use of the digital Information and Communications Technologies (ICT) (Wilson, 2012, p. 16; Koltay, 2011). It seeks to include the generation of competencies for critical comprehension and understanding to make informed decisions and comprehend the functioning of media and technology in general (Culver & Jacobson, 2012). It emphasizes the ethical treatment of media, information and technology, and their capacity to contribute in a positive way to democracy and to the empowerment of citizens. As Wilson (2012) declares:

MIL also involves an awareness of the right to access information, as well as the importance of using information and technology ethically and responsibly to communicate with others. Today, technology enables individuals to participate in intercultural dialogue as members of a “global village”. Within this “village”, possibilities for global citizenship can be explored, as responsible use of media and technology moves users from critical autonomy to critical solidarity as they connect with people from around the world. (p. 18)

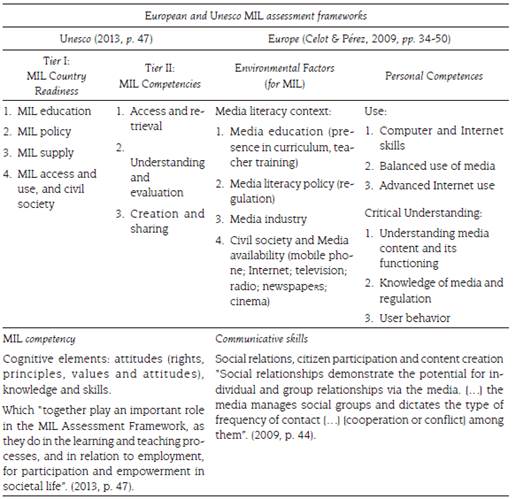

The scope and complexity of MIL have also been taken into account by the European Commission (2007; 2009), an institution which has generated guidelines and funded research on the subject (Frau-Meigs, 2012; Petranová et al., 2017), along with Unesco (2013, p. 47), to promote and assess MIL. In regard to Unesco, the evaluation proposal includes two levels. The first corresponds to the general framework of the context a nation must have to promote the development of MIL competencies, followed by a second level which defines the set of basic skills that ought to be achievable. The European framework (Celot & Pérez, 2009, pp. 34-50) also includes two levels: it labels the first one as environmental factors, with an intention similar to that of Unesco, followed by the elements which integrate the personal competencies, although it does not include the skills of creating and sharing in a specific and clear way that the United Nations agency does. Studies such as Emedus (Durán-Becerra & Tejedor-Calvo, 2015; Petranová et al., 2017), ANR Translit (Frau-Meigs, 2012), and COST “Transforming Audiences, Transforming Societies” (Frau-Meigs, Vélez & Michel, 2017) also highlight these merging points. In essence, both propositions coincide in their general proposal, stating that for MIL evaluation, it is necessary to assess both the general framework/ context of a country and individual competences of its citizens (table 1).

Table 1 Unesco’s Framework and European Framework

Source: Pérez-Tornero (2007), Durán-Becerra & Tejedor-Calvo (2015, p. 145).

The Association of College and Research Libraries (Association of College and Research Libraries [AC R L ], 2000, pp. 4-5), a leader and advocate of Information Literacy (IL), also defines the importance of acquiring skills and abilities leading to permanent learning in formal spaces of education, whereas an outcome ought to foster skills to locate, use, arrange and assess/value the required information (information need). Libraries, as actors of vital importance in the process, have undertaken the facilitation of IL (Uribe-Tirado, 2010; Ponjuán, Pinto, & Uribe-Tirado, 2015).

Governments, also as key actors, are or ought to be in charge of designing policies aimed toward the development of IL (Frau-Meigs, 2012). Media Literacy (ML) in turn, has been thoroughly developed by actors such as the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (Acara), which, in the framework of the National Assessment Plan (NAP), identifies evaluation elements related to ML and use of ICT. The National Assessment Program - ICT Literacy (NAP-ICTL) measures at the same time technological skills, IL skills, and knowledge in the general use of information. This with the purpose of generating communication skills (Ainley, Fraillon, Gebhardt, & Schulz, 2012, pp. 7-8), with an understanding of the set of characteristics and scenarios created by new technologies as an ecosystem which may generate opportunities and advantages (Katz & Koutroumpis, 2013).

Following the above-mentioned, this research establishes one general and three specific objectives. The general objective, as has been previously introduced, is to explore, analyze, and systematize the principal MIL related frameworks, research reports, and their practical applications. MIL must be understood as a complex concept, not only because it tries to integrate three dimensions and fields of study into one; it also has to be seen as a holistic approach that includes previous research close to the field (or in the same one), such as Educommunication (De Oliveira Soares, 2009), multiple literacies, new literacies and other related concepts that enrich its understanding and broaden its scope and reach globally

Specific objectives are to explore current literature on MIL; provide a broad understanding of the three principal approaches to MIL (media, information, and digital literacies) and; lastly, create a map of the MIL skills and competencies derived from the main theories reviewed.

Method

The approach in this article is based on a qualitative content analysis to map and systematize the principal MIL frameworks, research reports and practical applications of these frameworks. Therefore, categories (dimensions) are combined and correlated to establish individual indicators (skills and capabilities) and group them in subcategories (components) (tables 3 and 4). The meta-analysis is based on eighteen published works on MIL indicators and competencies that study frameworks and the disaggregation of indicators (Durán-Becerra, 2016). This paper also includes the analysis of three publications issued after the first study was published (Petranová et al., 2017; Frau-Meigs et al., 2017; Lopes et al., 2018). Thus, the research provides a good understanding of the three principal approaches linked to MIL (media, information and digital literacies) and the exploration of assessment proposals and systematization of indicators that develop the main MIL frameworks from the European Commission, Unesco, the Association of College and Research Libraries, the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority and tests such as A Media Literacy Quiz, B2i Brevet Informatique et Internet, the European Union survey on ICT usage, the PIAAC Background Questionnaire and PISA, among others - Similar outcomes from the analysis of these frameworks can be observed in Lopes et al. (2018), in their case to create a MIL test-.

The content analysis allows a good understanding of the meaning of different concepts and approaches to MIL as it explores their communicative context and social and cognitive senses. That is, the meaning or hidden/unveiled meaning a concept or speech has, which is related to their social, cultural, psychological, or historical production-consumption circumstances (Piñuel, 2002). Three major dimensions (categories) were set according to the initial literature review: media, information, and digital literacies (table 3). These dimensions, in turn, were composed by the following components: information priority; access; evaluation (critical comprehension); use; advanced use and limits/responsibilities (under the information dimension); use and advanced use (under the digital dimension); critical comprehension of media/knowledge of media’s context, use, critical comprehension, advanced use, citizen participation/ empowerment, limits/responsibilities (under the media dimension). In the end, these categories and subcategories led to a systematization and proposal of the main MIL related skills and capabilities (table 4).

OverviewDocs, an opensource Quantitative Descriptive Analysis (QDA) software was used to systematize and aggregate the skills and capabilities, which allowed the identification of referents, frameworks and academic research that support the proposed map of MIL skills and competences. OverviewDocs QDA was used by tagging skills and capabilities matching the different dimensions and components. The software aggregated the combinations gathered in a range of visualization tools included as default. The data were double validated to avoid any biases and downloaded in .xlsx format to process it in tables.

The methodological proposition is summarized in four tables included in this article (tables 1 to 4). The first one frames the general concept of MIL for evaluation purposes; the second one formulates a specific definition of the competences in question; the third one presents a summary of the dimensions and components of MIL; and the fourth one summarizes the final proposal, which includes a map of the MIL skills and competences derived from the main theories that were reviewed.

Results

In 2008, Unesco (2008, p. 19) proposed a series of parameters for the creation of IL indicators, building a “Map [or Constellation] of Communication Skills” divided into five levels of observation with different skills (which summarizes the propositions of Catts and Lau from 2009: information skills, skills in ICT, media skills, oral communication skills, and reasoning skills). On the other hand, in their study for the European Commission, Celot and Pérez (2009) initially established a formal approach to the evaluation of the MIL levels through a scheme that groups together individual competencies (use, understanding, critical thinking, communication skills) and praises the environmental factors (existence of policies in/for the media/media education, availability of the media and relation of the media industry with civil society) (Pérez Tornero & Durán Becerra, 2019). Unesco (2011b) explains that the described dimensions are grouped in two categories that define processes of measurement/assessment or generation of indicators. Category 1 refers to the factors that facilitate information development. Category 2 approaches those factors which create conditions of creation, availability, distribution, supply, and reception of information. It proposes three skill components that have a similar structure that serve to establish indicators for personal capacities (access, evaluation, and use).

Studies and Approaches to MIL

The different competencies in MIL research measurements may be grouped as part of DL (Digital Literacy), IL or ML. According to researcher Renee Hobbs (2010, p. 17), in the last fifty years, there have been enormous advances made in the theoretical field of media education due to the emergence of ICT. The existing typologies are a result of the spectrum created in different frameworks proposed by actors in relation to education policies, curricula, evaluation schemes or other types of academic activities (Pérez-Tornero & Durán-Becerra, 2019). These frameworks are an output from the concern to incorporate ICT in different social scenarios (Giraldo-Luque et al., 2014, p.7; Kanižaj, 2017).

An example of the aforesaid is the Development of Indicators on Individual, Corporate and Citizen Media Literacy research (Dynamic) -a study of the Office of Communication and Education of the Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, financed by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and directed by professor José Manuel Pérez Tornero- that analyzed 17 studies on the evaluation of competences related to MIL (Giraldo-Luque et al., 2014). The study confirms a trend towards the assessment of digital skills: 11 out of 17 studies work with aspects of DL, 6 of ML and 4 of IL. Out of the 696 questions individually analyzed, 280 focus on the component of use, 185 on critical thinking, 92 on communication skills, 79 on the availability of resources and 60 on the context for ML (Giraldo-Luque et al., 2014, p. 11).

Another basic reference for the creation of indicators to assess MIL levels is the report by the European Association for Viewers Interests and Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona (EAVI-UAB) for the European Commission (Celot & Pérez-Tornero, 2009, p. 35). This research model outlines specific criteria, components and indicators (Pérez-Tornero & Durán-Becerra, 2019). Ferrès and Piscitelli (2012, pp. 79-81), on the other hand, establish dimensions for MIL evaluation, they emphasize fields of analysis and fields of expression, studying the dimensions of: language, technology, interaction, production and diffusion, ideology and values and aesthetics. Renee Hobbs (2010, p. 19) proposes a map of essential competencies to design programs or evaluations for Digital and Media Literacy. These essential competencies (table 2) are core to many studies and have been part of large sets of MIL tests and assessment schemes proposed by different MIL actors (Lopes et al., 2018).

Table 2 Essential Competences of Digital and Media Literacy

| Essential Competences | |

|---|---|

| 1. Access | Finding and using media and technology tools skillfully and sharing appro priate and relevant information with others. |

| 2. Analyze & Evaluate | Understanding messages and using critical thinking to analyze message quality, veracity, credibility, and point of view, while considering potential effects or consequences of messages. |

| 3. Create | Composing or generating content using creativity and confidence in self-ex pression, with awareness of purpose, audience, and composition techniques. |

| 4. Reflect | Applying social responsibility and ethical principles to one’s own identity and lived experience, communication behavior and conduct. |

| 5. Act | Working individually and collaboratively to share knowledge and solve problems in the family, workplace and community, and participating as a member of a community at local, regional, national and international levels. |

Source: Hobbs (2010, p. 19).

The components described by Hobbs are similar to the proposals outlined in the previous paragraph, giving special importance to access, which in turn relates to the availability of infrastructure, and the individual capabilities on use (table 2). Likewise, the component understood as analysis and/or evaluation extends to what other authors describe as critical thinking (Frau-Meigs, 2012). In relation to the capabilities described above, Hobbs highlights the capability to create, describing it as an advanced use, which implies the possibility of generating content and interacting with platforms. The component related to the reflexive capabilities includes another frequently discussed research concern related to ethics of the communication processes (an aspect which has also included protectionist proposals concerning the use and consumption of media). Finally, the capability of acting, constructed on the latent objective of MIL, will impact the improvement of decision-making, to generate greater citizen involvement and thus promote their social participation (Culver & Jacobson, 2012; Giraldo-Luque et al., 2017).

Framework of MIL Competences

This section describes a classification of dimensions and components by outlining a comparative map of competences and skills. It gathers the contributions of the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL, 2000, p. 5), the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority Acara (Ainley et al., 2012, p. 7), Pérez-Tornero (2007, pp.18-19), Unesco (2008), Celot and Pérez-Tornero (2009, pp. 34-50), Lau and Cortés (2009); Hobbs (2010, p. 19), Unesco (2011b, pp. 14-15; 2013, pp. 56-60) and Giraldo-Luque et al. (2014) 1, as well as the findings of Emedus (Durán-Becerra & Tejedor-Calvo, 2015; Petranová et al, 2017), ANR Translit and COST projects (Frau-Meigs et al., 2017).

Table 3, shown below, is a summary that simplifies the variables observed by the different theoretical frameworks previously analyzed (dimensions). In turn, each of the components defines skills and competences. The components of each of the studied literacies (dimensions), as well as their related skills, are explored in full in table 4 and explained in the following paragraphs.

Table 3 Summary of the MIL Dimensions and Components

| Dimension | Component |

|---|---|

| A. Information |

|

| B. Digital |

|

| C. Media |

|

Source: Durán-Becerra (2016, p. 135).

Table 4 Map of MIL Skills and Competences

| Dimension | Component | Skill / Capability |

|---|---|---|

| A1. Information priori ty | Identifying information needs. | |

| A. Information | A2. Access | Seeking/locating information and contents. Accessing information and contents. |

| Recovering and storing information and contents. | ||

| Organizing and systematizing information. | ||

| A3. Evaluation / critical comprehension | Understanding (reading comprehension) the consulted con tents and information. | |

| Evaluating the consulted information. | ||

| Evaluating the source/provider of information. | ||

| Evaluating the consulted resource. | ||

| Differentiating types and formats of texts. | ||

| Classifying and validating localized webpages/sites. | ||

| A4. Use | Using the consulted information with a specific purpose. | |

| Creating, sharing and reproducing information and contents. | ||

| Applying learned contents. | ||

| A5. Advanced use | Using the consulted or produced information and resources ethically. | |

| Using ICT resources and services for information and content creation responsibly. Participating in social or political activities through networks or in person, in an informed manner. | ||

| Monitoring the influencing capacity and effects of consumed media and information. | ||

| A6. Limits/ responsibi lities | Understanding the legal, economic and social context of information, content and the media (rights, duties, respon sibilities). | |

| B1. Use | Accessing information/ICT skills. | |

| Using Internet for general purposes. | ||

| Creating and consuming content and information. | ||

| B. Digital | B2. Advanced use | Using online banking. |

| Buying products online. | ||

| Online working. | ||

| Studying online (eLearning/education use of digital learning platforms). | ||

| Generating complex ICT tools (programming skills and te chnical analysis). | ||

| C. media | C1. Use | Cognitive capabilities that allow the use of media and Information. |

| Using communication tools. | ||

| Using social networks. | ||

| Consuming online news. | ||

| Creating content. | ||

| Accessing, creating and reproducing information and content. | ||

| C2. Critical compre hension | Reading, understanding and evaluating media, information or cultural content. | |

| Classifying types and formats of texts. | ||

| Understanding the behavior of users. | ||

| Classifying webpages/sites according to type and properties (quality, officials, etc.). | ||

| Classifying digital platforms and understanding their cha racteristics. | ||

| Being mindful of the functioning and interests of media and providers when consuming contents/resources in general. | ||

| C3. Critical unders tanding of media / knowledge of the media’s context | Understanding how the media works (functioning logics, interests, belonging to corporate groups). | |

| Understanding the regulations governing media, especially on the contents, information and cultural goods in general. | ||

| Understanding the characteristics of the media’s environ ment (political system, concentration, plurality). | ||

| C4. Advanced use | Participating in advanced uses of the Internet (purchases, online work, etc.). Using media in a balanced way (comprehensively, conside ring limitations and responsibilities, and without generating dependency). | |

| Creating contents according to audiences. | ||

| Creating interactive and creative contents. | ||

| Making advanced ICT decisions (security, programming, ethical and legal use). | ||

| Using the information, contents and consulted/created media ethically and responsibly. | ||

| C5. Citizen participation / empower ment | Participating in social or political activities through networks or in person, in an informed manner (active citizenship). | |

| Using government services online. | ||

| Monitoring the influencing capacity and effects of the con sumed information/media. | ||

| Using the Internet to promote cooperation. | ||

| Using web-based services (social networks, requests, media, etc.) for the demonstration of opinions and political control. | ||

| C6. Limits/ responsibi lities | Knowing the regulations governing media and the responsi bilities deriving from it. | |

| Knowing the regulating authorities and the legal procedures to interpose complaints or appeals. | ||

| Understanding copyright (intellectual property, economic rights and use/reproduction rights). |

In table 4, the first dimension (A) comprises the components related to information literacy. The component (A1) of information priority is defined as the capability to determine the amount of information needed for the development of a specific task or project (ACRL, 2000, p. 5; Unesco, 2008; 2011b, p. 14; Lau & Cortes, 2009). It is a set of skills that allows the correct management of information (Ainley et al., 2012), the identification of the specific information requirements for performing a task, or for the fulfillment of an information need. The access component (A2) deals with the capability to access information in an efficient and effective manner while knowing the means of access (mechanisms, platforms, codes, etc.), ensuring agility and satisfaction of the specific information needs (ACRL, 2000, p. 5; Unesco, 2008; Ainley et al., 2012). Pérez-Tornero (2007, pp. 18-19) emphasizes the physical access to media and its contents, which implies the existence and possession of technological components and equipment (Celot & Pérez-Tornero, 2009, pp. 34-50). This is understood as opportunities (which implies an element of context and not only skill) (Lau & Cortes, 2009; Hobbs, 2010, p. 19; Unesco, 2013, pp. 56-60).

The evaluation component (A3), also described as critical comprehension, deals not only with critically evaluating the consulted/consumed information, but also the resources employed, so they can be efficiently transformed into knowledge (ACRL, 2000, p. 5; Ainley et al., 2012). It integrates a set of skills necessary to judge the integrity, relevance and benefits of information, while being supported by ICT tools. The evaluation and critical reading capabilities (technical and cognitive) are skills to read, understand and evaluate the offered media products and contents (Pérez-Tornero, 2007, pp. 18-19; Unesco, 2008). It is also the capability to classify audiovisual and written texts (into typologies and formats) to differentiate content, classify and validate webpages/sites, with the objective of inducing and deducing information elements/ideas (Lau & Cortés, 2009; Hobbs, 2010, p. 19; Celot & Pérez-Tornero, 2009, p. 35). Unesco (2013, pp. 56-60) indicates that the processes of IL shape the skills for healthy media consumption.

The component of use (A4) is defined as the set of skills that allow the collection of information for a specific purpose (ACRL, 2000, p. 5), towards the creation of new knowledge (Ainley et al., 2012). The capability of communicating the use of the consulted information (Unesco, 2008, 2011b, pp. 14-15) favors processes of creation, information processing (evaluation/understanding), application of acquired knowledge and reproduction of consulted/recovered information (Lau & Cortes, 2009; Hobbs, 2010, p. 19; Unesco, 2013, pp. 56-60; Giraldo-Luque et al., 2014).

The fifth element (A5) is advanced use, related to the responsible use of ICT (Ainley et al., 2012) with more complex communication processes, such as the capability of exchanging information and knowledge and/or creating information products adjusted to the audience, context and medium in an ethical manner (Unesco, 2008; 2011b, pp.14-15; Lau & Cortés, 2009). It implies identifying procedures and behaviors related to online security and protection (Celot & Pérez-Tornero, 2009, p. 35). It also links individual capabilities focused on promoting participation in public and social activities as active citizens (Unesco, 2013, pp. 56-60). The last component (A6) within this dimension is concerned with the limits and responsibilities that the individual ought to understand in regard to the legal, economic, and social context surrounding information, with the aim of respecting the rights, duties and responsibilities derived from the author rights, as well as their ethical and legal use (ACRL, 2000, p. 5; Unesco, 2008; 2011b, pp. 14-15; 2013; Lau & Cortes, 2009).

The second dimension (B) is associated with DL, which is constantly linked to Information and Media literacies. In Promoting Digital Literacy (Pérez-Tornero, 2004, pp.18-19) the component of use (B1) is defined as the physical access to media and its content and meaning, in other words as the real possibility of use that allows the user to consult and handle resources (Durán-Becerra, 2016). This set of skills are mostly technical and are described by Unesco (2008) as every skill which allows the use of ICT, basically computer and Internet-browsing skills (Celot & Pérez-Tornero, 2009, pp. 34-50). In 2011, Unesco (2011b, pp. 14-15; Giraldo-Luque et al., 2014) started emphasizing that the digital component deals with using ICT to process information and produce user-generated content (Leaning, 2017; Lopes et al., 2018). The advanced use component (B2) is then defined as the set of capabilities/skills necessary for the design and construction of ICT solutions for the storing of information and the making of ICT decisions that are critical, strategic and reflective (advanced and balanced use) (Ainley et al., 2012, p. 7; Durán-Becerra, 2016).

The third dimension (C) is Media, whose first component (C1) studied within this dimension is use. It is defined as the cognitive and practical skills that allow the proper enjoyment of media (Pérez-Tornero, 2007, pp. 18-19), and the understanding of different kinds of communication tools and networks (informative, social, professional) (Unesco, 2008). It also highlights the skills related to the use of the Internet (Celot & Pérez-Tornero, 2009, p. 35; Unesco, 2013, pp. 56-60; Giraldo-Luque et al., 2014). Renee Hobbs (2010, p. 19), in turn, directly relates use with access as a first step, and with the capability of accessing, consulting, using and generating content, in a second moment.

The second component (C2) is related to critical comprehension, which implies the understanding of content and information, and the conscious consumption of cultural and media products. It is a set of skills to read, understand and evaluate media content and products as defined by Pérez-Tornero (2007, pp. 18-19) and understood by Unesco (2008, 2013, pp. 56-60). Hobbs (2010, p. 19) emphasizes the components of analysis and evaluation of information (reading competence), which are also highlighted in other studies that aggregate various researches (Celot & Pérez-Tornero, 2009, pp. 35-36; Giraldo-Luque et al., 2014).

The third component (C3) is the critical understanding of media meaning and/or knowledge of the context of media. This factor includes capabilities of understanding the functioning of media and its content, as well as critical identification of media content and concentration of media ownership (or its plurality) (Vedel, García-Graña, & Durán-Becerra, 2017; Celot & Pérez-Tornero, 2009, pp. 34-50). This concept implies having knowledge of the regulation of media, of its authorities, and penalizing procedures related to media. In the words of Thierry Vedel, also the “basic protection, market plurality, political independence and social inclusiveness” of media (Vedel et al., 2017, 3). Unesco (2011b, pp. 14-15) and different studies on MIL policy (Frau-Maigs et al., 2017; Pérez-Tornero & Durán-Becera, 2019) also highlight the need of knowing the role and functions of media in democratic societies (Orozco, 1997).

The fourth component of this dimension, advanced use (C4), is understood as in the information dimension: it entails advanced actions on the use of technology and therefore, the digital dimension (Pérez-Tornero, 2007, pp. 18-19; Ainley et al., 2012, p. 7). It is the capability of making critical, strategic and reflective ICT decisions (Celot & Pérez-Tornero, 2009, pp. 34-50). This component implies sophistication of the web, the use of the Internet for online government cooperation or services, and also a component of protection and security (Giraldo-Luque et al., 2017).

The fifth component (C5) is about citizen participation and empowerment. This component has also been identified with the concept of “user-centrism” (Celot & Pérez-Tornero, 2009, pp. 34-50), expressed, among other things, by the use of public services online. It implies the capability of acting collectively and individually to share knowledge and solve problems, and to participate as a member of local, regional, national and international communities (Hobbs, 2010, p. 19). It may be understood as the capability to use media for personal expression and democratic participation (Unesco, 2011b, pp. 14-15, 2013; Giraldo-Luque et al., 2014).

Lastly, the sixth component, limits and responsibilities (C6), is understood as the capability of valuing the social, legal and ethical nature of the problems treated by media and handled/used and reproduced by other agents (media-related or otherwise) and by users, as well as their regulation (Ainley et al., 2012, p. 7; Celot & Pérez-Tornero 2009, pp. 34-50). Renee Hobbs (2010, p. 19) establishes that this component is related to the different skills that allow a person to reflect on the uses, information scope, ethics and social responsibility of our communication behavior and conduct.

Proposed MIL Dimensions for Evaluation Purposes

Keeping in mind the characteristics of each of the described dimensions, the following map of MIL skills and competences is proposed under a holistic approach to media and information components (Durán-Becerra, 2016):

This map of MIL skills and competencies is the result of the analysis of the sets of skills, variables, capacities and observation units proposed by the authors and organizations referred earlier in the paper. Aggregated under three single dimensions, the map offers a systematization that will allow further research on MIL curriculum design, MIL evaluation or assessment tools, MIL policy guidelines and similar outcomes. Similarly, it is understood as a guide of dimensions for evaluation purposes, but its effectiveness is still to be set. Skills and competencies described derive from a robust examination and systematization that takes into account some of the most relevant studies and frameworks on MIL.

Conclusions

The work of international institutions and world-renowned organizations has been crucial in the development of Media and Information Literacy as a discipline. The role of researchers and universities has been supported by this kind of institutions; therefore, the construction of frameworks for the measurement or creation and design of strategies to strengthen MIL competences is the result of such individual and institutional foundations. The identification of MIL competencies is also the result of different efforts that have yielded some construct proposals for evaluation and assessment.

However, the research scope of such works is not easily assessable, because studies on measurement of competencies generally imply emphasizing the digital component on the use of technology in the processes surrounding media consumption and use of computers in different routines and citizen daily activities, while including components related to the creative and constructive capability of digital tools. Therefore, the need to promote behaviors, and critical and responsible use of both media and information content is normally left aside -a gap that is addressed in the MIL map proposed in this paper-.

In any case, the limitations of other frameworks may be given by the complexity and plurality of definitions surrounding MIL. The competency framework exercise proposed in this paper focuses on strengthening critical skills that allow citizens to have a better adaptation to its social space and promoting their active participation and contribution to MIL processes. This compilation has the goal to set a model for future evaluation proposals and a guide to introduce MIL in national curricula and education policies. Its viability and strengths lie in its ample work and systematization of the current MIL conceptualizations and research.

Even though the need for further research is a must, competency evaluation and systematization exercises like the offered here allows a better understanding of the complexity of the subject and the urgency to improve its framework. In this sense, the scheme proposed in the MIL map of skills and competences constitutes a structured effort to enable the creation of a next generation of methodologies and strategies for the visibility, promotion, strengthening and evaluation of MIL.