Introducción

Although sexuality is lived bodily, bodies -and their practices- have a cultural meaning. The regulations of sexual and romantic life are, in fact, prescribed and proscribed by various spaces, ways and rites (Machado-Pais, 2003). In this sense, masculinity and femininity are complex systems of socially constructed gender norms and refer to sets of practices, norms, beliefs, and mandates that organize and regulate gender appropriate expression of emotions, behaviors, bodies, and sexuality (Tolman et al., 2016). In every culture, boys and girls are socialized in particular forms of behaviors that are expected from them (Hlavka, 2014; Kågesten et al., 2016). Gender norms and their influence on the behavior of individuals from different cultural groups have extensively been studied. Traditionally, masculinity ideology refers to behavioral characteristics associated with men such as assertiveness, sexual impulsiveness, repression of emotions, exercise of power over others, and assigns to men the role of protector and provider for his female partner, having irresistible sexual desire, and avoiding feminine behaviors or attitudes. Meanwhile, traditional femininity ideology assigns to women characteristics as being responsive, caring, avoiding conflicts, preserving relationships, curbing hunger, repressing anger, and maintaining control over their impulses (De Meyer et al., 2017; Tolman et al., 2016). The study of masculinity and femininity has received much attention in Latino populations, among whom traditional gender roles have been found to be clearly defined and strongly endorsed (Singleton et al., 2016).

This strong endorsement of traditional gender ideologies has been conceptualized as machismo and marianismo and they describe a complex interaction of social, cultural and behavioral components forming gender role identities in the context of Latino societies (Sequeira, 2009; Singleton et al., 2016). Machismo has been described as a «cult of virility», since it associates male behavior with «exaggerated aggressiveness and intransigence in male-to-male interpersonal relationships and arrogance and sexual aggression in male-to-female relationships», and includes the man’s role of being authoritarian within the family, promiscuous, virile, but also protective for women and children (Sequeira, 2009; Walters & Valenzuela, 2020). Marianismo, in turn, refers to an «excessive sense of self-sacrifice» found among traditional Latino women. The term is derived from the name Maria, the mother of Jesus Christ, and entails the concepts of female virginity, chastity, honor and shame, the ability to suffer and willingness to serve; implying that an ideal woman is virtuous, humble, pure, non-sexual, spiritually superior to men and submissive to men’s demands (Da Silva et al., 2018; Sequeira, 2009).

Several studies have documented how traditional gender roles exert pressure on adolescents in their romantic relationships and sexuality. For instance, Latina girls had reported stricter rules about dating. They are supposed to maintain their virginity until marriage, and to plan to marry and have children (Milbrath et al., 2009). Additionally, Latino adolescents had not only been found to report lower levels of sex-related activities in their romantic relationships (Len-Ríos et al., 2016), but also report gender-based differences in their experiences (Bouris et al., 2012). Yet, as the vast majority of studies on gender roles with Latino populations has been developed in North America, these has implied that the participants were in a context of immigration and in a condition of belonging to a minority group, thus being confronted with the challenge of negotiating sexuality in a cultural context that differs their home country (Raffaelli et al., 2012). Hence, scholarly work is still scarce on the role and dynamics of gender roles in adolescents developing in Latin-American countries.

To date, most studies focusing on traditional gender ideologies have addressed these constructs separately. However, there is a growing interest in analyzing the meaning and consequences of traditional gender ideologies within the context of a romantic relationship. So far, it has been documented that traditional masculinity ideology has been associated with lower quality of romantic relationships, and with increased risk of unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases (Mirandé, 2018; Wade & Donis, 2007), while traditional femininity ideology has been associated with difficulties in women to express their sexual desires and with involvement in unwanted sexual behavior (Impett et al., 2006; Minowa et al., 2019). Additionally, it has been suggested that masculinity and femininity ideology can work in tandem to perpetuate and reproduce gender hierarchies (Tolman et al., 2016). Moreover, the dynamics of relationships based on traditional gender ideologies have been found to be associated with partner and sexual violence (Hlavka, 2014). These associations become important when it has been recognized that romantic relationships play an important role in the psycho-emotional development of adolescents (Furman & Shaffer, 2003), and that they are the primary context in which adolescents learn and develop different facets of sexuality (Bouris et al., 2012).

Taken together, these findings imply the need to explore and better understand how traditional gender ideologies might generate specific dynamics in romantic relationships in adolescents, especially in a Latin American context, where a high endorsement of traditional ideologies is expected.

Mixed-Methods Approach

The present study used a mixed-method approach including concurrent triangulation. With the use of the mixed approach, it was intended not only to comprehend the trends in the perceptions of adolescents, but also to understand how these perceptions are reflected in the behavior of adolescents within a couple relationship. In the quantitative exploration, validated self-report questionnaires were used to measure the patterns of endorsement of traditional gender ideologies. Simultaneously, using qualitative indepth interviews we explored romantic experiences of the adolescents in order to understand how these are shaped by gender roles.

The study was conducted in Cuenca, a city in Ecuador where important social processes are taking place, such as alarming data on sexual health in adolescents with adolescents pregnancy (Ministerio de Salud Pública, 2017), strong endorsement of a double standard in parental education (Jerves, 2014), together with the deficiency of comprehensive sex education programs, creating an interesting context to explore adolescents’ romantic experiences relationships in a Latin American country.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Cuenca after reviewing the study design, research protocol and the tools to be administered. Permission was obtained from the local Board of the Ministry of Education. Participants were informed about the aims of the study and were told that some survey questions would address personal issues. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. All the participants who were invited consented to participate and they signed an informed consent and received a snack and a drink after completing the survey.

Quantitative exploration

The quantitative survey study aimed at providing insight in major trends in the endorsement of gender ideologies by adolescents. Based on a literature review, it was hypothesized that men would endorse traditional gender ideology to a greater extent than women (Kågesten et al., 2016). Secondly, based on findings linking socio-economic class and the endorsement of traditional gender ideologies (Levant & Richmond, 2008), adolescents from public schools would endorse traditional gender ideologies to a greater extent than adolescents from private schools.

Participants and procedures

Using a database provided by the local board of the Ministry of Education, a cluste-redrandomized approach resulted in the survey being conducted in six -3 public and 3 private- high schools in the city of Cuenca. The research protocol and methods were discussed with high school authorities.

Measures

Demographics were obtained and included: sex, age and type of school. Prior to the selection of the tools, a literature review was carried out to establish the main characteristics of the machismo and marianismo. These main characteristics were contrasted with scales and the questions of the several tools used to assess gender role ideologies. Among several tools, Male Role Norms Inventory-Revised Version (MRNI-R) (Levant, Smalley et al., 2007), and the Femininity Ideology Scale (FIS) (Levant, Richmond et al., 2007) were selected.

The MRNI-R was used to measure endorsement of masculinity traditional ideology. The tool consists of 53 questions, in which participants indicate their level of agreement or disagreement with ideology items of traditional masculinity on 5-point Likert-type scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The scale contains seven subscales reflecting different dimensions of traditional masculinity ideology, including: Avoidance of Femininity; Negativity Toward Sexual Minorities; Self Reliance; Aggression; Dominance; Non-Relational attitudes towards Sexuality; and Restrictive Emotionality. The psychometric qualities of the scale and subscales have been reported (Levant, Richmond et al., 2007). In the current sample, Cronbach’s alpha for the Total Scale was .93.

The FIS was used to measure the endorsement of femininity traditional ideology. The tool consists of 45 questions, in which participants indicate their level of agreement or disagreement with items on traditional femininity ideology on 5-point Likert-type scales, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The scale contains five subscales to assess different dimensions of traditional femininity ideology, including: Stereotypic Image and Activities; Dependency/Deference; Purity; Caretaking; and Emotionality. The psychometric quality of the FIS has been reported (Levant, Richmond et al., 2007). In the current sample, Cronbach’s alphas for the Total Scale was .89.

As the original scales were published in English, a standardized process of translation was conducted followed by a pilottest in the target group to identify possible difficulties in understanding the tests. One item of FIS and two of the MRNI-R that referred to cultural elements were reworded to fit the Ecuadorian context.

Statistical analysis

Demographic characteristics are presented as frequencies and percentages. The distribution of participants at different levels of attitudes towards the traditional ideologies was compared. For this purpose, the results of the MRNI-R and FIS scales were categorized as follows: average total scores between 1 and 2 were classified as «rejection»; average total scores between 2 and 4 were classified as «uncritical acceptance»; and, average total scores between 4 and 5 were classified as «adherence» to traditional ideologies. Both the MRNI-R and the FIS provided information on general trends -total scale- and on specific trends by subscales. The results indicated that the established trends in the total value of the scale were maintained in the subscales, so the analysis was performed based on the total values.

Chisquare tests for independence were used to compare distributions of the population in different groups. For cases in which the conditions to correctly perform a Chisquare test were violated a Fisher’s exact test was used. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to explore the association between total traditional masculinity and femininity scores. The level of significance was set at p <.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 18.0.

Results

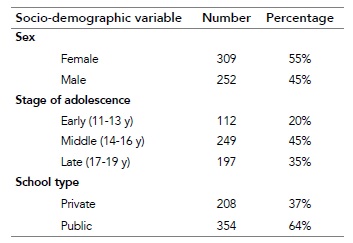

In total, 562 participants (55% girls) completed the survey of which 20% belonged to the early, 45% to the middle, and 35% to the late stage of adolescence. In respect to the school type, 37% of the participants belonged to a private school. And, in respect to the romantic involvement, 87% of participants reported they already had had at least one romantic partner and 46% reported to be involved in a current romantic relationship (table 1).

Results showed that, as a general trend, most adolescents could be classified as uncritical to both traditional masculinity and femininity ideologies with only small proportions being classified as rejecting and even less as adhering to traditional gender ideologies.

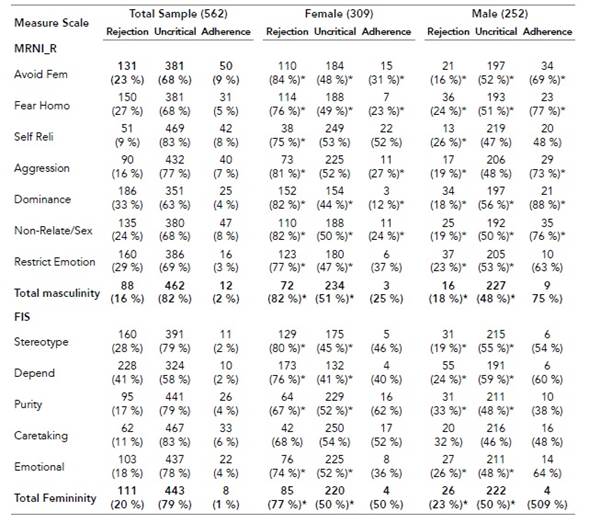

Group comparisons showed that when comparing female and male adolescents, a significant association was found between sex and attitudes towards Total traditional masculinity ideology x2 (2) =33.3, p=.000, and towards Total traditional femininity ideology x2 (2) = 25.85, p =.000 (Fisher’s Exact test=.000). Based on calculated residuals, it was possible to identify that higher proportions of female adolescents could be classified as rejecting, while higher proportions of male counterparts could be classified as uncritical or adhering to traditional gender ideologies (table 2).

Table 2 Frequencies and Percentages on MRNI-I and FIS according to the Sex

Note. An asterisk indicates a significant difference between the means in that row *p<.05.

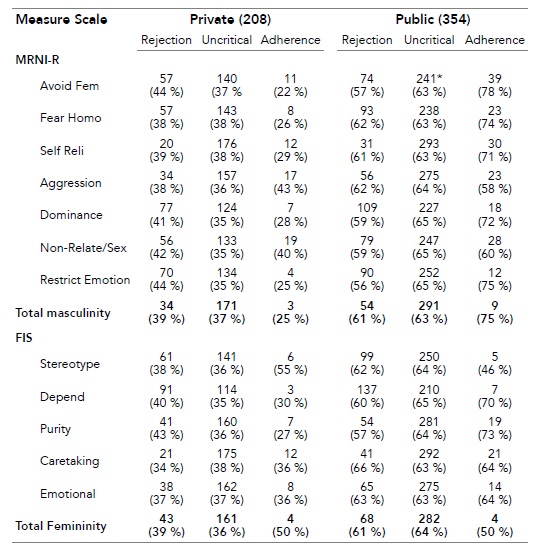

There were no significant differences based on the type of school for both traditional masculinity ideology x2 (2) = .842, p =.656 (Fisher’s Exact test = .728) and traditional femininity ideology x2 (2) = .806, p =.668 (Fisher’s Exact test =.604). See table 3.

Discussion of the quantitative study

The majority of adolescents were classified as being uncritical towards traditional ideologies of masculinity (82%) and femininity (79%). For those that were classified as taking position, it was found that more participants showed a tendency towards rejecting rather than adhering. Thus, contrary to the main starting hypothesis of this study, adolescents from Cuenca did not endorse traditional masculinity and femininity ideologies, but showed a tendency to be uncritical which may implicitly invoke an acceptance and reproduction of these traditional gender ideologies.

A comparison of different groups based on sex and type of school, provided support for one of starting hypotheses for this study.

The first hypothesis suggested a sex-based difference (Kågesten et al., 2016). Findings showed that more male adolescents could be classified as uncritical, and more female adolescents could be classified as rejecting traditional gender ideologies. In the context of gender inequity, it is not surprising that male adolescents are rather uncritical to traditional ideologies as these allow them to maintain their position of power. In the same line of thought, it seems that a part of female adolescents reject the traditional gender ideologies and therewith show discomfort with the current situation in which they develop, and start to question their own (prescribed) role within the society, results that coincide with the warning of Machado (2012), who observes that despite the persistence of traditional values and customs regarding the role of women, young women have a tendency to free themselves from these convictions.

Secondly, it was hypothesized that adolescents attending public schools would be more adhering towards traditional gender ideologies (Kågesten et al., 2016). The findings of this study do not support this hypothesis since adolescents in private and public schools did not differ in their patterns. Being that adolescents attending private or public schools mainly differ in socioeconomic status, these findings suggest that traditional gender ideologies are equally rooted in the different social groups.

Qualitative exploration

A qualitative interview study was conducted to explore the gender ideologies in the experiences of adolescents within the context of romantic relationships.

Participants and procedures

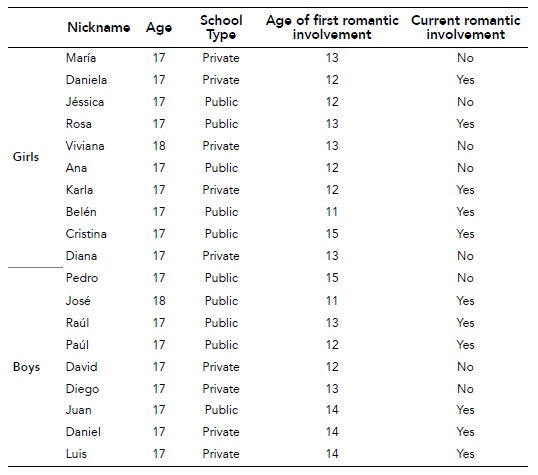

The qualitative study relied on a purposive sample of male and female late-stage adolescents who were recruited from the same high schools that participated in the survey study, in a process where the psychologists of the institutions acted as legitimate gatekeepers. The final sample consisted of 20 adolescents (10 female) of ages between 17 and 18 years old (M=17.1). Characteristics of the sample are shown in table 4.

The interviews were conducted in Spanish. The duration of the interviews varied between 60 to 90 minutes. All interviews were audio-recorded to enable verbatim transcription afterwards.

The semi-structured interview started with open questions focusing on narratives of their experiences of first romantic involvement. In a second moment, the interview shifted to participant’s experiences in and reflections on their most recent or current romantic relationship.

Data analysis

Analysis started with an open coding of adolescents’ accounts using thematic analysis. The research team who conducted the analysis was made up of both Ecuadorian and international educational psychologists, ortho-pedagogues and a family therapist. Through constant comparisons between the data and emerging codes, certain themes were established. The initial coding was done in Spanish by the Ecuadorian team members. Based on this coding, a map of codes and themes was structured, which was then analyzed and discussed with the international members. For this, the quotes that exemplified each code and theme were translated into English. Different strategies were used to enhance the reliability of the coding. Several discussion sessions were conducted with members in order to identify and adjust the discrepancies in the analysis. The analysis was facilitated through the use of ATLAS.ti 7.1 software.

Results

It is important to mention that both adolescents from private and public schools participated in the sample, but that at the time of the analysis, no elements were established that indicate differences in the experiences of adolescents based on this classification, thus coinciding with the findings of the quantitative study. Which indicated that the support patterns do not differ according to the type of educational institution. More-over, Although men and women were interviewed in the study, their perspectives pointed to similar patterns in both expectations and experiences, that is, men and women had similar expectations of men and women in a relationship of couple.

In this sense, the data was analyzed according to the emerging themes that shape the expectations and experiences of adolescents within a couple relationship. Beyond the traditional models, the qualitative exploration made it possible to visualize the way in which these models of masculinity and femininity shape the behaviors within the couple relationship, qualifying them in relationships of tension and, often, suffering. Here, the study identified three main themes in participants’ accounts on their experiences: 1) Un-critical acceptance of traditional gender role norms; 2) families promoting a sexual double standard; and, 3) normalization of psychological violence.

Uncritical acceptance of traditional gender role norms

In keeping with the trend to uncritically accept traditional models, in the narratives of the participants, boys were presented as strong, unemotional, and guided by their sexual urges; while girls were presented as weak, vulnerable, dependent and guided by emotions.

Boys being unemotional, and guided by their sexual desires

Boys were consistently presented as strong, not showing fear, sadness, worries, suffering or needs for support, thus restricting their emotions.

Juan (male): I never show my feelings! It can happen that I am sad; however, I will always show a smile for the rest not to realize about my sadness.

Most participants accounted for the ways boys demonstrate their strength through dominance and aggressiveness. With romantic partners, male strength is shown as dominance. In fact, most participating girls indicated that their romantic partners constantly gave them orders regarding the clothes they should wear, activities they could do, and even friendships they can (or cannot) have.

David (male): She [the girlfriend] should not be able to do anything without consulting me, or at least asking me for permission.

With other boys the male strength was demonstrated through aggressiveness. Consistently, stories of threats and fights between boys were frequently heard in their narratives. Nevertheless, while boys told these stories with pride and no signs of fear, girls introduced these stories as representing a constant fear for the possibility that boyfriends could assault their friends or cousins.

Maria (female): He was jealous of my cousin, so when I go out with him, he always asks me: «so what? Are you dating?» And I say «no! He is my cousin!» But one day, he saw us together and he yelled at me all his repertoire of insulting words and tried to beat my cousin! It was horrible!

Additionally, boys were presented as conquerors and womanizers «by nature». This meant that boys were motivated to look for partners who seem difficult to conquer, and the more difficult, the more motivated they felt. However, this also means that once conquered, the partner loses her appeal generating a feeling of disappointment.

Juan (male): For me, she was like an illusion, she was the girl who took me longer to conquer, and the more you crave something that you don’t have (…) that when you get it, you realize that it is not as wonderful as you thought.

In turn, this willingness of boys to conquer the impossible was also present in the stories of girls who indicated that -as a reaction- they preferred to turn themselves into «difficult to conquer» or «become worshiped». However, this clearly generated confusion in girls.

Karla (female): that day, when I met him, I didn’t like him so I treated him badly! And after that he told me that he loves me? So the question is, do I have to mistreat them? I do not like to mistreat boys (…) but I see that that is what they like!

Related with this desire for conquest, the majority of participants’ accounts included stories of infidelity on the part of boys, and boys having more than one partner at a time. It seems that unfaithfulness in men was normalized in such a way that girls accepted and condoned it.

Finally, another important element is the view that boys were driven by sexual impulses. It is, however, noteworthy to mention that none of the boys commented on their sexual experiences. This means that the view of «men as driven by sexual impulses» is based on the narratives of most of the girls, who indicated to constantly feel pressured by the sexual urges of their romantic partners. In the stories of girls, two types of experiences could be identified. First, some reported how boys seek for sexual advances while girls feel uncomfortable with these attempts.

Karla (female): He was so sexual! I mean, he just wanted to keep on kissing and those kinds of things, and I could not talk to him anymore, as soon as he arrived he started kissing me (…) and no! I didn’t like it.

Second, one girl expressed that, from the initiation of an active sexual life, the boys’ desire for sex became the centre of attention in the relationship, while she still yearned to share other activities and other kinds of expressions of love such as tenderness and care.

Jessica (female): After we had sex for the first time, everything changed because he just wanted sex. Before, we used to go dancing and sometimes he was nice to me, but after that he always wanted sex, sex and sex.

Interestingly, when female participants were asked about whether their romantic partner was sexually active, some participating girls answered: «not with me! With others, I guess…» which revealed that the sexual behaviour of boys outside the romantic relationships are not uncommon and somehow, accepted.

Girls being vulnerable and passive

Most participants described girls as weak, vulnerable and in need of permanent male protection, thus dependent.

Belen (female): Once we went out there was a drunk man who came to me and started bothering me. He [boyfriend] defended me and that made me feel good.

However, boys interpreted the weakness of girls also as a possibility of being dominated.

David (male): I was so surprised when she showed herself weak to me, then I realized that I had the control.

Another important characteristic is that girls are not expected to take the initiative within a romantic relationship, but that they are always expected to wait for boys to do so. The passivity of girls was reflected in many aspects of the relationship such as decision-making, or expressing desires. In this regard, some male participants indicated that this passivity became uncomfortable for them because all the responsibility for the relationship fell on them.

Luis (male): For example, if I asked «where would you like to eat?» She said «I do not know, you choose». I always had to make the decisions, especially in important things like when we went through difficulties, she always expected me to decide. I ended up monopolizing the relationship.

Moreover, the passivity of girls was also directly related to their inability to refuse sexual advances by their romantic partners. Thus, some girls indicated that they felt un-comfortable, but that they did not know how to express their discomfort or stop their partner in his advances. As a consequence, some preferred to separate from their partners and one of the participants expressed that her active sexual life started in a context of coercion.

Jessica (female): When we had our first time [sexual intercourse], it was supposed to be all-nice, but it was not. I didn’t feel like it but he told me: «If you didn’t want to have sex, why did you make him feel like it?» Then, we did it because of him, so that he could be with me and so that he could feel happy. But after that, I felt abused by him.

Girls as redeemers

The participants’ accounts further revealed that the main role for girls was caring for and protecting their partners. However, unlike the care that boys provided, i.e., to protect girls from other men, girls were supposed to protect their romantic partner against their own inherently negative behavior, i.e., self-destructive (e.g., drug and alcohol abuse) or against things that were harmful for the relationship (e.g., aggressiveness and infidelity). In this sense, girls were described as what could be understood as the redeemers for boys.

Jose (male): She has changed me a lot; she has done to me something that no one else has ever done. I mean, I used to drink, and she helped me quit this vice.

Associated with their role as redeemers, girls were described to present certain characteristics such as patience, capacity to forgive and ability to persuade through words. However, not all the girls were able to fulfill this role, but only those who were considered «girls that are worthy», that is -according to their narratives- girls who remain at home who do not attend social events and who have not had romantic partners previously.

Carlos (male): If you really want something serious with a girl, and then you realize that she is going out too much, then you think, she is not worthy.

Girls rejecting sexual expressions

Girls were presented as not interested in sexual expressions beyond kissing and hugging. There were no narratives showing a possible expression of sexual desire in girls. Even more, some participating girls considered their romantic partners sexual-affective expressions as a lack of respect for them. Related with this, they expressed and stressed purity and virginity to be an important value for girls.

Cristina (female): It is a relationship based on respect because he knows very well that we will not have sex, because we know what we feel for each other. I think a woman must be respected. My plan is to remain virgin until marriage. Then, when I get married, I will give myself to my husband.

Families promoting a double standard

According to the participants’ accounts family plays an important role in shaping the double standard in romantic relationships, through both differences in the expectations for romantic involvement as well as in the freedom granted to boys and girls.

Different expectations for romantic involvement

While boys were encouraged to a romantic involvement at an early age, girls were not allowed to have a romantic partner. It is, however, clear that both boys and girls haven been involved in romantic relationships. In this regard, while most boys did not explain clearly why they felt motivated to start their romantic relationships early, one boy explained that the reason for him was his father’s fear that his son could become a homo-sexual.

David (male): My dad persuaded me to have a girlfriend. When I started high school, he told me to hang out with several girls. I think he instilled me that because he thought that otherwise my sexual orientation could be deviated.

In girls, the restriction to get involved in romantic relationships was directly associated with the fear of an unwanted pregnancy.

Rosa (female): My grandparents would not let me have a boyfriend. They said I could get pregnant even with a kiss!!

Differences in freedom

All participating boys were free to go out and act without controlled schedules or activities. However, most participating girls were restricted and could only go out at specific times, and if so, they should always be accompanied by members of their family or by female friends.

Jose (male): The parents of my girlfriend are very strict, then she is not allowed to go out, except when she goes out with her parents (…) Instead, I can go out from my house at seven in the morning and return at eleven in the evening and that bothers her.

This implies that the majority of experiences with romantic relationships evolve in the context of school, and when these occur outside school, they occur in hidden places.

Karla (female): Since my parents didn’t let me out, then boys chose to bring me to suspicious hidden places so that nobody could see us, such as the riverside for example. But I know that they go there to have sex, then, I don’t like it.

Partner violence normalized in the experiences of adolescents

The participants’ stories were marked by tension and negative emotions, directly related to expressions of control and jealousy between the partners.

Maria (female): When you are in a relationship, you have to tell your partner everything that you do, or to see your partner whether you want it or not.

Here, although boys and girls exert control toward partners, boys and girls experienced this differently. When boys exert control, this is understood as a form of protection. Overall, control was exercised through the use of mobile devices with permanent chats that allowed a remote control. There were also accounts of boys personally supervising and monitoring their partner, with the particularity that this permanent presence was described to be explicitly aimed at controlling the partner.

Maria (female): He used to call me every five minutes. He asked: «where are you?» I told him that I was at my friend’s house and he asked: «what are you doing?» I didn’t like him to be so worried all the time, however, that made me feel protected.

When girls exert control, this is rather perceived as harassment, and leads to rejection.

Paul (male): It is ugly when someone follows you so much! She called my house, she called my sister; she called my friends! It should not be like that!

Jealousy as an expression of love

A frequently heard element in the narratives of the participants was that jealousy is an expression of love.

Viviana (female): It was incredible! He really loved me so much that he tried to make me feel jealous, to test whether I really loved him. He had this idea that when your partner is not jealous, she does not love you.

Jealousy isolating girls of their social support

While in cases that women were jealous, this often was related to other women who, in their view, constituted a threat for the relationship; in the case of men, jealousy was presented not only to potential suitors of their partners, but also to male and female friends, and even members of the family -especially cousins.

Thus, the jealousy of boys isolated girls of their social core. Here, girls were initially distanced from male friends, but also gradually they distanced from cousins, female friends and family. This was even stronger when the romantic couple attended the same school -as in most cases- where girls were pressured to share it with their romantic partners and were expected to renounce sharing time with their female friends.

Partner violence compounded by lack of communication with family

In the participants’ narratives, several stories included partners’ discussions, shouting, threats, sudden separations, stress and crying of girls. Although there were few situations involving physical violence, and only one explicit narrative of sexual violence by coercion (Jessica), the majority of narratives included references to psychological violence and manipulation which generated feelings of powerlessness in girls, and fear of the reaction of boys.

The powerlessness of girls was complicated by a lack of support from their families. Indeed, it became clear that the female participants in our study could not communicate with their parents about their romantic relationships.

Romantic relationships felt as a heavy burden

Several participants expressed to experience romantic relationships as negative for their lives and stated that having a romantic partner was felt as a heavy burden. In the same line, some participants expressed fear of getting involved in romantic relationships because of the great suffering that was associated with it.

Cristina (female): When guys approach me and they are my friends all is well; but if they start saying «you’re beautiful» and things like that (…) I say, «No! You know what? I’m afraid to fall in love!»

It also became clear that being in a romantic relationship sometimes was felt as a constraint to their lives, and some participating adolescents described having a romantic relationship as being in prison.

Daniela (female): When I have a boyfriend I feel so imprisoned. I have to cover myself; I do not want anyone to see me because I think if maybe he [the boyfriend] is around and sees that some guy looks at me, he gets jealous.

Discussion of the qualitative study

The narratives of the participants were marked by a clear presence of traditional gender models reflecting the existing discourses on machismo and marianismo and revealing some of the ways in which these are translated into specific behaviors within romantic relationships.

In coherence with what has been named as gender complementarity (Tolman, Spencer et al., 2003; Tolman, Striepe et al., 2003), the experiences of the adolescents showed how the feminine model promoted by marianismo invokes a traditional machista attitude, the idealized model of women, i.e., marianismo allows the idealized model of men, i.e., machismo, to exist and be asserted. This finding reinforces the need to work not only on new masculinities, but also on new models of femininity that strengthen the position and expectations of women in a relationship.

Another important finding of this study has to do with the double standard imposed by the adolescents´ parents. It seems that this double standard creates additional vulnerability for adolescents as their romantic relationships develop mostly clandestinely. In a context of gender inequality -where partner violence is frequent-, a lack of communication implies that adolescents cannot count on family as a source of support. This imposition of roles by families is especially important in the sense that, as Machado (2012) has emphasized, adolescents build their life guides from what they incorporate from their closest beings, from their family.

Consistent with the meaning of machismo and marianismo, the narratives of male and female adolescents revolved around a romantic vision -with a limited discourse on sexual behavior- of partner relationships (Len-Ríos et al., 2016). In boy’s narratives, a discourse about sexual behavior was completely absent. This is striking because there is the idea of men being driven by sexual impulses. However, boys might probably conceive the development of sexual experiences outside romantic relationships and, therefore, when talking about romantic relationships stayed silent about their sexual behavior. In turn, girls’ narratives reflected a kind of denial of the existence of sexual desires and emphasized how rigid traditional ideologies illegitimate such desire (O’Sullivan et al., 2007).

Thus, girls’ experiences revolved around their role of evading unwelcome sexual urges from their partners. Previous studies have showed that this role of being the «gatekeepers » of boys’ sexual urges, puts all the responsibility for prevention in girls as well as blames them in cases of coercion or sexual violence, for not fulfilling their role of resisting sexual advances of men (Hlavka, 2014). Additionally, consistent with the concept of strict separation of gender roles, narratives on homosexuality were completely absent in adolescents’ accounts.

Finally, the findings of this study evidenced that partner violence -mainly psychological violence, but also sexual violence by coercion- is a common theme in romantic relationships during adolescence. Beyond, this study provided important insight about how traditional gender ideologies account for the violent dynamics.

General discussion

This mixed-method study allowed exploring the endorsement of traditional gender ideologies in adolescents living in Cuenca, a traditional city in Ecuador. This exploration provided a preliminary insight in some of the ways in which these traditional ideologies foster stereotyped behavior in boys and girls and turn romantic relationships into spaces of gender inequity, that are characterized by tension and negative emotions resulting in vulnerability for both partners (Singleton et al., 2016; Tolman et al., 2016).

In this mixed-methods study the quantitative and qualitative approach complement each other. Here, the results of the quantitative exploration showed that the majority of adolescents in Cuenca can be classified as non-critical in relation to traditional gender ideologies, while the narrative accounts developed in qualitative exploration showed the way in which these ideologies are translated in behaviors within romantic relationships. In fact, the emerging codes and themes in the experiences and interpretations of adolescents regarding their romantic relationships clearly match the characteristics of machismo and marianismo evaluated through the quantitative tools’ subscales.

Here, while most studies until now have focused exclusively on machismo and thus on male behavior within a relationship, the present study indicated the role of marianismo in the formation and maintenance and hegemony of machismo. Indeed, it was found that machismo and marianismo are systemically intertwined, resonating with previous studies on the complementarity of gender constructions (Terrazas-Carrillo, 2019; Tolman, Spencer et al., 2003; Tolman, Striepe et al., 2003) but also reinforcing the need to deepen the understanding of marianismo and in the need to work on new models of the feminine for adolescents.

Additionally, qualitative data showed that adolescents’ behavior within romantic relationships reflected a strong double standard according to which girls are limited in their behaviors while boys had all freedom. However, it was clear that both boys and girls reported to have had romantic relationships; yet, these are held in secrecy for most of the girls. Such a double standard may create a risk for the sexual development to both parties (Singleton et al., 2016; Tolman et al., 2016). First, because of the marianismo-related expectations for women, the expected sexual experience of male adolescents must be acquired outside of a romantic relationship, leading men to learn to dissociate sexuality from romantic emotions. Second, women -who are expected to deny their sexuality- have no opportunity to learn skills needed for a healthy sexual development and may have less access to health care services and related information (Da Silva et al., 2018; Impett et al., 2006). Thus, the characteristics of romantic relationships found in participants’ accounts may play an important role in the persistent high number of adolescents’ pregnancies and high prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases as well as high rates on partner violence that are persistent in Ecuadorian society.

Gender inequity based on traditional ideologies, inhibits male and female adolescents from building mutually satisfying and respectful romantic relationships. In this context, romantic relationships might also become negative experiences associated with fear, helplessness, power conflicts, and coercion. In a social context where expectations about romantic relationships are connected with machismo and marianismo, adolescents will probably not feel encouraged to recognize or prevent negative behaviors within a relationship, thus romantic relationships can become dysfunctional spaces that could affect healthy emotional growth of the adolescent (Giordano, 2003).

Although this study has yielded interesting results, some limitations are noteworthy. First, the study was developed in a specific socio-cultural context therefore the findings could not be extrapolated to other cultural and contextual settings. Second, the study was limited to adolescents attending secondary education. Since education has been found to be an important factor in the development of gender ideologies, it is possible that adolescents who have no access to secondary education have different experiences and perspectives. Third, given the findings showing that in Cuenca romantic relationships are subject to control and repression by adults, it is possible that social desirability has played an important role. Furthermore, it is possible that the characteristics of age, education and social position of the interviewers my have inhibited the adolescents to talk in deep about their experiences, specially those related to a sexual behavior inside romantic relationships. Fourth, the current study was based on cross-sectional data and thus does not allow for inferences about causality or longitudinal interpretations of the findings. Finally, In a context of diversity and social and economic inequity such as Cuencan society, further studies could enrich the understanding of gender roles from an intersectional perspective.