Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

International Law

Print version ISSN 1692-8156

Int. Law: Rev. Colomb. Derecho Int. no.16 Bogotá Jan./June. 2010

ARGUMENT ANALYSIS OF THE POSITION OF COLOMBIA REGARDING THE UN DECLARATION ON THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES*

ANÁLISIS DE ARGUMENTACIÓN SOBRE LA POSICIÓN DE COLOMBIA FRENTE A LA DECLARACIÓN DE NACIONES UNIDAS SOBRE LOS DERECHOS DE LOS PUEBLOS INDÍGENAS

José Fernando Gómez-Rojas**

* This article is and adjusted version of a paper elaborated for the Discourse Analysis: Principles and Methods course, led by Professor Des Gasper, during my Masters Degree in Development Studies at the Institute of Social Studies, ISS, The Hague, the Netherlands, 2008-09. I would like to thank Professor Gasper for his careful feedback on the structure of this paper.

** Bachelor of Laws, LLB, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana (2004). Specialist in Analysis and Resolution of Armed Conflicts, Universidad de los Andes (2007). Masters Degree in Development Studies, Specialization in Human Rights, Development, and Social Justice, Minor in Civic Action and Social Movements, Institute of Social Studies, ISS (2009). Currently, consultant lawyer in human rights, development, and international law.

Contact: jfgomezr@gmail.com.

Reception date: 10 de febrero de 2010 Acceptance date: 12 de marzo de 2010

TO CITE THIS ARTICLE / PARA CITAR ESTE ARTÍCULO

José Fernando Gómez-Rojas, Argument Analysis of the Position of Colombia regarding the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, 16 International Law, Revista Colombiana de Derecho Internacional, 143-176 (2010).

ABSTRACT

This is the final result of an investigation. This article seeks to analyse the discourse elaborated by the Colombian Government concerning the adoption of the text of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples within the General Assembly, on September 13th, 2007. In doing so, Stephen Edelson Toulmin and Michael Scriven's methods of argument analysis will be proposed, basically stressing on the clarification of some meanings, the (un)stated conclusions, the (un)stated assumptions, and an overall evaluation of the discourse. The main purpose of this document is to analyse the relationship between texts, co-texts, and contexts, and their influence within politics and international law. The analysis of these interactions would help policy-makers and academics gain more room for manoeuvre in regard to problem and priority-setting scenarios.

Key words author: Indigenous peoples, United Nations, Declaration, discourse, text, context.

Key words plus: Indians of South America, Civil Rights, Discourse Analysis, Indian's Rights.

RESUMEN

Éste es el resultado final de una investigación. El presente artículo pretende analizar el discurso elaborado por el Gobierno colombiano en relación con la adopción del texto de Declaración de Naciones Unidas sobre los Derechos de los Pueblos Indígenas en el marco de la Asamblea General, el 13 de septiembre de 2007. Para ello, se proponen los métodos de Stephen Edelson Toulmin y Michael Scriven sobre análisis argumentativo, para aclarar el significado de algunas frases, identificar las conclusiones y supuestos directos e indirectos, así como una evaluación general del discurso estudiado. El propósito principal de este artículo es intentar analizar la relación entre textos, co-textos y contextos, y la influencia de estos conceptos frente a la política y el derecho internacional. El análisis de estas interacciones puede ayudar a quienes diseñan políticas públicas o a la academia, con el fin de lograr un mayor margen de maniobra en relación con escenarios de identificación de problemas y prioridades.

Palabras clave autor: Pueblos indígenas, Naciones Unidas, Declaración, discurso, texto, contexto.

Palabras clave descriptor: Indígenas de Suramérica, derechos civiles, análisis del discurso, derechos de los indígenas.

SUMMARY

INTRODUCTION.- I. COLOMBIA AND THE UN DECLARATION.- A. Quick context.- B. Difficulties of the text: text and co-text.- C. Text structure.- D. Overall evaluation of the discourse.- II. A NEW POLITICAL POSITION? A. Unilateral declaration of support to the UN Declaration.- B. Text analysis.- C. Overall evaluation of the discourse.- CONCLUSIONS.- BIBLIOGRAPHY.

INTRODUCTION

The study of development policy is normally not connected with policy discourse and methods of analysis.1 Effective discourse analysis requires systematic attention to both text and context.2 Furthermore, when talking about policy practice, it is crucial to mention framing, which means "what and who is actually included, and what and who is ignored and excluded".3 According to Gasper,4 "this framing cannot be settled by instrumental rationality, precisely because it frames that".

In that sense, this article is an attempt to study the formal discourse of the Colombian Government vis-à-vis the international community with respect to the adoption of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (herein after the UN Declaration). The article consists of two main parts. In Part I, a brief context of the Declaration will be mentioned. Secondly, I will pose the difficulties found when analysing this discourse. Thirdly, the text of the vote explanation of the Colombian Government regarding its abstention from voting (whether against or in favour of) the UN Declaration will be presented. Thereafter, I will structure the text in distinct parts in order to provide the meanings of key words, the main conclusions, the stated and unstated assumptions and the overall evaluation of the text. In Part II, a similar analysis will be presented regarding a recent unilateral declaration of the Colombian Government before the UN General Secretary concerning the support of this Government to the principles and values of the UN Declaration. Finally, some conclusions will be made.

I. COLOMBIA AND THE UN DECLARATION

A. Quick context

Texts often depend on contexts.5 The Declaration process was not pacific due to long-term difficulties in terms of opposing interests between (nation) states and indigenous communities, as it can be described as follows:

- With an overwhelming majority of 143 votes in favour, only 4 negative votes cast (Canada, Australia, New Zealand, United States) and 11 abstentions, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples on September 13th, 2007. The Declaration has been negotiated through more than 20 years between nation-states and Indigenous Peoples.6

- Since its establishment in 1995, the Working Group on the Draft Declaration has met annually but although the adaptation of the draft Declaration was recommended in the First International Decade's programme of activities, this did not happen. In 2005 the mandate of the Working Group was renewed but the continued lack of progress in adopting the Universal Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples is a cause of great concern.7

- Finally, September 13th, 2007 is the date when a final text was adopted by the UN General Assembly through the Resolution 61/295.

B. Difficulties of the text: text and co-text

Given that the text under analysis consists of more than 1400 words, it is not easy to choose which part deserves more consideration than another, especially due to an apparently cohesive structure in the argumentation of the Colombian government. Therefore, it is not easy to separate a text from a co-text which could be often inter-related. I chose as the text the main reasons why, from the Government's point of view, the UN Declaration would contradict the interests/values of the Colombian state. Consequently, the co-text consists of the previous considerations ("grounds" in terms of Stephen Edelson Toulmin)8 that provided the justifications for the abstention of the Colombian Government.

C. Text structure

I found that I needed -wanted- to concentrate on a sub-section of the text. It depended on what I considered forms a sufficiently self-contained section, as it involves all the components of an argument analysis. Having recognised the difficulties encountered when attempting to choose between text and a co-text, I decided to separate the eighteen (18) paragraphs of the discourse as follows:

- Particularities of the Colombian Indigenous Peoples and their national legal protection (paragraphs 1 to 5).

- The position of the Colombian State in the international arena regarding indigenous issues (paragraph 6).

- Cooperation with the Colombian Indigenous Peoples and policy-making (paragraphs 7 to 8).

- The arguments (grounds) for the abstention of Colombia (paragraphs 9 to 17).

- Final statements (paragraph 18).

Herein I reproduce the full text of the explanation of vote:9

- "The Colombian State has incorporated into its legal system a broad range of rights aimed at recognizing, guaranteeing and implementing the rights and constitutional principles of pluralism and national ethnic and cultural diversity.

- In the framework of its 1991 Constitution, Colombia has distinguished itself as one of the most advanced countries with regard to the recognition of the collective rights of Indigenous Peoples. According to the indigenous legislation index of the Inter-American Development Bank, Colombia is first in terms of the quality of its legislation in the sphere of cultural, economic, territorial and environmental rights, as well as in terms of the overall quality of its indigenous legislation.

- Our diversity is reflected in the existence of 84 Indigenous Peoples. According to the 2005 census, some 3.4 per cent of Colombians identify themselves as belonging to indigenous communities. For the Colombian State, the recognition of the traditional territories of those communities is fundamental. Today there are 710 reservations occupying an area of approximately 32 million hectares, corresponding to 27 per cent of the national territory. By the end of 2007, that area should extend to 29 per cent of the national territory. Those properties cannot be proscribed, seized or transferred. Indigenous peoples access to collective or individual land ownership is regulated by legal and administrative provisions guaranteeing that right, in keeping with the State's objectives and with principles such as the social and ecological functions of ownership and State ownership of the subsoil and nonrenewable natural resources.

- In these territories, Indigenous Peoples carry out their own political, social and legal organization. By constitutional mandate, their authorities are recognized as public State authorities having a special nature. As far as the legal area is concerned, a special indigenous jurisdiction is recognized, which is significant progress compared with that made by other countries in the region.

- Reservations participate in the central Government's budgetary transfer system. It should also be noted that all members of these communities are covered by the State-subsidized health service. In addition, the law establishes that Indigenous Peoples are exempt from compulsory military service -an essential provision aimed at preserving their cultural identity. And there are special electoral districts for Indigenous Peoples in national political elections.

- In the international context, Colombia has been a leading country in implementing the prior-consultation provisions of International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention 169, to which our country is a party. Since 2003, 71 prior-consultation proceedings have been undertaken for natural resource prospecting and extraction projects and other development projects in established indigenous territories.

- Cooperation with indigenous communities is a priority for the State. In this area, there are permanent forums such as the national coordination board, the national rights commission, the Amazon regional board and the national territories board. Those forums have made it possible to jointly elaborate norms and policies concerning indigenous communities from a multiethnic and inclusive perspective.

- In order to continue these activities over the long term, the State, with participation by indigenous experts, is currently developing a comprehensive policy for indigenous communities, crucial aspects of which are related to, inter alia, territories, human rights and self-government.

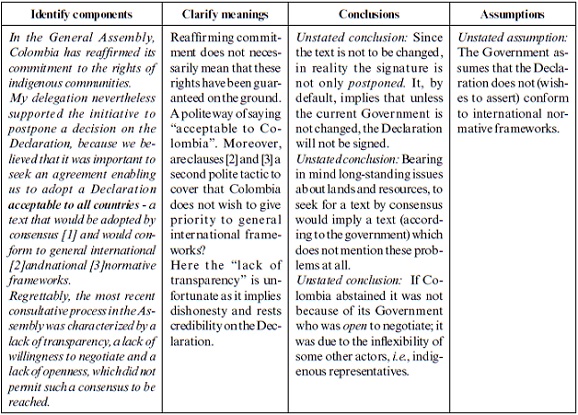

- In the General Assembly, Colombia has reaffirmed its commitment to the rights of indigenous communities. My delegation nevertheless supported the initiative to postpone a decision on the Declaration, because we believed that it was important to seek an agreement enabling us to adopt a Declaration acceptable to all countries -a text that would be adopted by consensus and would conform to general international and national normative frameworks. We even supported the establishment of a forum that would have enabled indigenous communities to participate in the discussion. Regrettably, the most recent consultative process in the Assembly was characterized by a lack of transparency, a lack of willingness to negotiate and a lack of openness, which did not permit such a consensus to be reached.

- The Colombian constitution and body of law, as well as the international instruments ratified by our country, conform with most provisions of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. However, while the Declaration is not a legally binding norm for the State and in no way constitutes the establishment of conventional or customary provisions that are binding for Colombia, my delegation finds some aspects of the Declaration to be in direct contradiction with the Colombian internal legal system, which obliged us to abstain in the voting. I shall refer briefly to some of these.

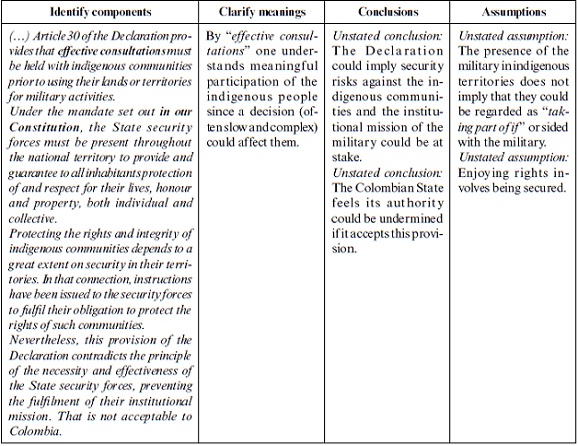

- For example, article 30 of the Declaration provides that effective consultations must be held with indigenous communities prior to using their lands or territories for military activities. Under the mandate set out in our constitution, the State security forces must be present throughout the national territory to provide and guarantee to all inhabitants protection of and respect for their lives, honour and property, both individual and collective. Protecting the rights and integrity of indigenous communities depends to a great extent on security in their territories. In that connection, instructions have been issued to the security forces to fulfil their obligation to protect the rights of such communities. Nevertheless, this provision of the Declaration contradicts the principle of the necessity and effectiveness of the State security forces, preventing the fulfillment of their institutional mission. That is not acceptable to Colombia.

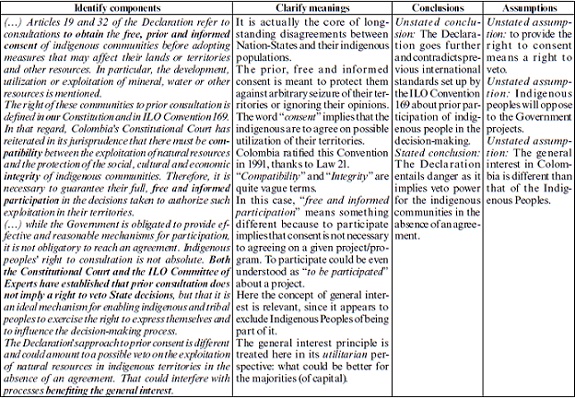

- Moreover, articles 19 and 32 of the Declaration refer to consultations to obtain the free, prior and informed consent of indigenous communities before adopting measures that may affect their lands or territories and other resources. In particular, the development, utilization or exploitation of mineral, water or other resources is mentioned.

- The right of these communities to prior consultation is defined in our constitution and in ILO Convention No. 169. In that regard, Colombia's Constitutional Court has reiterated in its jurisprudence that there must be compatibility between the exploitation of natural resources and the protection of the social, cultural and economic integrity of indigenous communities. Therefore, it is necessary to guarantee their full, free and informed participation in the decisions taken to authorize such exploitation in their territories.

- However, that Court has indicated that, while the Government is obligated to provide effective and reasonable mechanisms for participation, it is not obligatory to reach an agreement. Indigenous peoples' right to consultation is not absolute. Both the Constitutional Court and the ILO Committee of Experts have established that prior consultation does not imply a right to veto State decisions, but that it is an ideal mechanism for enabling indigenous and tribal peoples to exercise the right to express themselves and to influence the decision-making process.

- The Declaration's approach to prior consent is different and could amount to a possible veto on the exploitation of natural resources in indigenous territories in the absence of an agreement. That could interfere with processes benefiting the general interest.

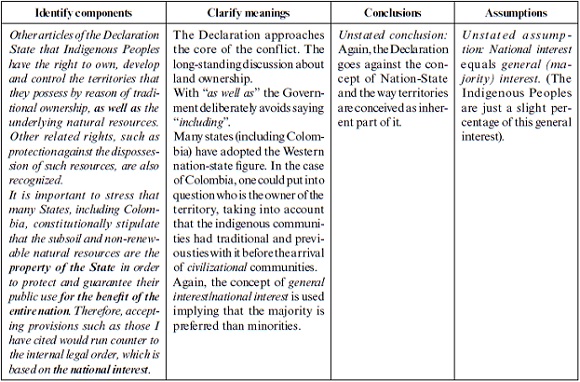

- Other articles of the Declaration state that Indigenous Peoples have the right to own, develop and control the territories that they possess by reason of traditional ownership, as well as the underlying natural resources. Other related rights, such as protection against the dispossession of such resources, are also recognized. It is important to stress that many States, including Colombia, constitutionally stipulate that the subsoil and nonrenewable natural resources are the property of the State in order to protect and guarantee their public use for the benefit of the entire nation. Therefore, accepting provisions such as those I have cited would run counter to the internal legal order, which is based on the national interest.

- Moreover, the Declaration refers to archaeological and historical sites as well as to lands and territories, without clearly defining the concept of indigenous territories, which is relevant to achieving effective protection in terms of the rights of peoples and the obligations of the State.

- Finally, Colombia has been and will continue to be a country committed to facts and realities in protecting the rights of Indigenous Peoples, from a realistic and participatory perspective that harmonizes national identity with the development of the State, to which all Colombians belong. The decision to abstain in the voting on this text because of the legal incompatibilities that I have identified does not change the State's firm national commitment to implementing the constitutional provisions, internal norms and assumed international obligations aimed at preserving the Colombian nation's multi-ethnic nature and protecting its ethnic and cultural diversity."10

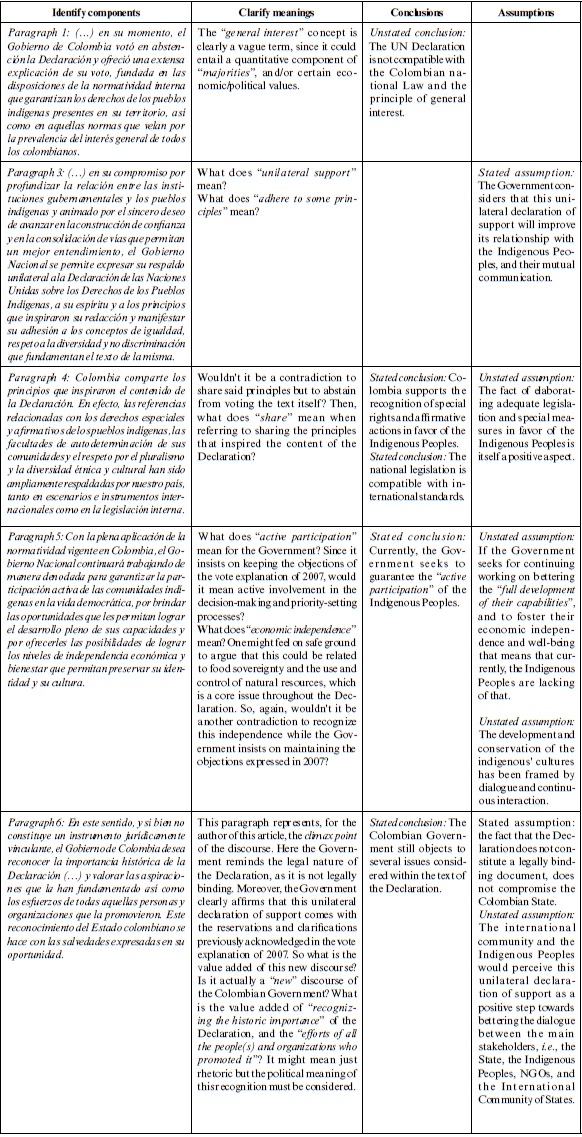

As it can be seen, the objective of this discourse is to provide a full explanation of the reasons of the abstention of Colombia for voting in favour -or against- the UN Declaration. Following the Stephen Edelson Toulmin model of argumentation11 the three central elements in argumentation are the claim, the grounds and warrants. With respect to the claim, one could argue that the Colombian Government abstained from voting this international document due to "insolvable contradictions" with the national legislation -including the Political Constitution, as mentioned in paragraph 10. From paragraphs 9 to 17 it provides the grounds for this claim and from paragraphs 1 to 9 it uses context as a way of implying possible warrants.

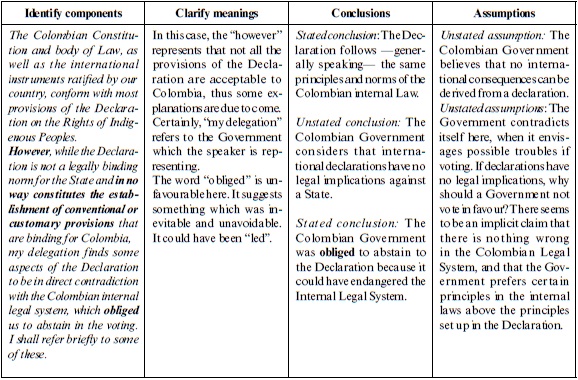

However, the present article explores the argumentation of the Colombian Government in accordance with the seven-step model for argument analysis, delivered by Michael Scriven.12 In that sense, I will clarify some meanings of specific terms, as well as identify the stated and unstated conclusions, the stated and unstated assumptions and an overall evaluation of the discourse. Therefore, I will proceed to propose paragraph 10 as the climax or the turning point of the discourse:

Paragraph 10: Colombia recognises Indigenous Peoples' rights but:

I considered this paragraph as the climax of the discourse because after having presented a series of positive measures in favour of the Indigenous Peoples and after having mentioned that the Declaration coincides generally with the Colombian internal legal system, the speaker continue with a however followed by the rest of the paragraphs, implying that the Declaration still has some possible troubles and alleged contradictions in respect to the Colombian law which are about to be explained. These possible troubles are reproduced through the grounds of the argumentation. In this case, the grounds of the argumentation are the reasons that obliged the Colombian Government to abstain from voting as a way of protecting "its" national values.

Ground 1 - Paragraph 9: The lack of consensus during the negotiation13

Ground 2 - Paragraph 11: The military responsibility of the Colombian State14

Ground 3 - Paragraphs 12 to 15: Prior, free and informed consent could mean a veto power

Ground 4 - Paragraph 16: State ownership of the natural resources

Ground 5 - Paragraph 17: Ambiguity in the concept of Indigenous Territories

D. Overall evaluation of the discourse

Having analyzed the vote explanation, one could say that this was the logic of argumentation of the Colombian government:

- Positive context of the Colombian Indigenous Peoples.

- Although there is a positive context, signing the Declaration could imply contradictions with the National Legal System.

- Several reasons are given in order to explain the abstention.

- Conclusion of the vote explanation reaffirming the Colombian compromise in favour of the Indigenous Peoples.

One can also analyse the five big arguments of the Government explaining the reasons why it abstained from voting the UN Declaration of Indigenous Peoples. They can be synthesized as follows:

- The lack of consensus during the negotiation.15

- The military responsibility of the Colombian State.

- Prior, free and informed consent could imply a veto power.

- State ownership of natural resources.

- Ambiguity of the concept of Indigenous Territories

Apart from the military responsibility of the Colombian State, one can even go further and inter-relate the other four arguments as related to a common issue: land rights. In fact, the lack of consensus was due to different perspectives on who is the owner of land. As a consequence, if the concept of indigenous territories is not fully defined -as it appears to happen in paragraph 17-, the Indigenous Peoples have been considered as a threat to future development projects as these communities could apply a veto power using the prior, free and informed consent. The Government goes deeper and implies that Indigenous Peoples could be in opposition to a general interest which is not adequately explained in this discourse.

As it was mentioned below, I consider paragraphs 1 to 9 as the context of the case. Furthermore, it is worth to note that the context here is matched with the co-text. In other words, the cotext is about the context of the rights situation of the Indigenous Peoples in Colombia, from the point of view of the Government. At the same time, as it is stated, this context/co-text is also used as warrant, as all the aspects mentioned can be considered as positive measures in favour of the Indigenous Peoples. This can lead the reader to envisage two possible interpretations:

- Colombia has a positive environment for its Indigenous Peoples and it will continue supporting that through this UN Declaration, or

- Colombia has a positive environment for its Indigenous Peoples but it will pose some questions on accepting the Declaration.

If the second interpretation is taken as the Colombian Government does, surely "certain" readers could note that it is not that bad that the Declaration was not signed since the situation for the Indigenous Peoples in Colombia is already positive. Hence, it will be of no harm for the indigenous the fact that the UN Declaration is not signed up. In fact, paragraph 18 -the last one- ends up with reaffirming the Colombian compromise.

II. A NEW POLITICAL POSITION?

A. Unilateral Declaration of support to the UN Declaration and the context of its emergence

The Deputy Minister for Multilateral Affairs of Colombia, during her intervention before the Durban Review Conference in Geneva, on April 21st, 2009, stressed that:

- [E]n su compromiso por profundizar la relación entre las instituciones gubernamentales y los pueblos indígenas y animado por el sincero deseo de avanzar en la construcción de confianza y en la consolidación de vías que permitan un mejor entendimiento, el Gobierno nacional hará entrega en el día de hoy, de una nota dirigida al Secretario General de las Naciones Unidas en la que expresa su respaldo unilateral a la Declaración de las Naciones Unidas sobre los Derechos de los Pueblos Indígenas, a su espíritu y a los principios que inspiraron su redacción. En este sentido, y si bien no constituye un instrumento jurídicamente vinculante, el Gobierno de Colombia desea reconocer la importancia histórica de la Declaración de las Naciones Unidas sobre los Derechos de los Pueblos Indígenas y valorar las aspiraciones que la han fundamentado, así como los esfuerzos de todas aquellas personas y organizaciones que la promovieron.16

It is not a minor issue the fact that the Government of Colombia acknowledged its unilateral support to the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples at the Palais des Nations in Geneva, before the President of the Durban Review Conference, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, and the representatives of the participant States. Indeed, the Durban Review Conference was meant to assess and accelerate progress on the implementation of measures taken at the World Conference against Racism, held in Durban, South Africa, 2001.17 So as part of the Plan of Action, the Colombian Government might have considered this unilateral support as an open manifestation of willingness regarding its relationship with the Indigenous Peoples.

With respect to the diplomatic note elaborated by the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Colombia sent to the UN General Secretary, which was acknowledged by the Deputy Minister for Multilateral Affairs, this article analyses its text below. I decided to separate the text in seven (7) paragraphs as follows:18

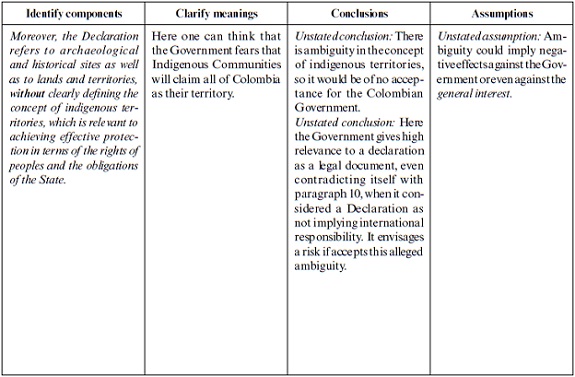

- Como Su Excelencia recordará, en su momento el Gobierno de Colombia votó en abstención la Declaración y ofreció una extensa explicación de su voto, fundada en las disposiciones de la normatividad interna que garantizan los derechos de los pueblos indígenas presentes en su territorio, así como en aquellas normas que velan por la prevalencia del interés general de todos los colombianos.

- El Gobierno Nacional ha mantenido su espíritu de diálogo con las comunidades indígenas, que se ha visto particularmente fortalecido a partir de las sesiones de trabajo establecidas desde octubre de 2008, con ocasión de la Minga social promovida por algunas organizaciones indígenas en Colombia.

- Por ello, en su compromiso por profundizar la relación entre las instituciones gubernamentales y los pueblos indígenas y animado por el sincero deseo de avanzar en la construcción de confianza y en la consolidación de vías que permitan un mejor entendimiento, el Gobierno Nacional se permite expresar su respaldo unilateral a la Declaración de las Naciones Unidas sobre los Derechos de los Pueblos Indígenas, a su espíritu y a los principios que inspiraron su redacción y manifestar su adhesión a los conceptos de igualdad, respeto a la diversidad y no discriminación que fundamentan el texto de la misma.

- Colombia comparte los principios que inspiraron el contenido de la Declaración. En efecto, las referencias relacionadas con los derechos especiales y afirmativos de los pueblos indígenas, las facultades de autodeterminación de sus comunidades y el respeto por el pluralismo y la diversidad étnica y cultural han sido ampliamente respaldadas por nuestro país, tanto en escenarios e instrumentos internacionales como en la legislación interna.

- Con la plena aplicación de la normatividad vigente en Colombia, el Gobierno Nacional continuará trabajando de manera denodada para garantizar la participación activa de las comunidades indígenas en la vida democrática, por brindar las oportunidades que les permitan lograr el desarrollo pleno de sus capacidades y por ofrecerles las posibilidades de lograr los niveles de independencia económica y bienestar que permitan preservar su identidad y su cultura.

- En este sentido, y si bien no constituye un instrumento jurídicamente vinculante, el Gobierno de Colombia desea reconocer la importancia histórica de la Declaración (...) y valorar las aspiraciones que la han fundamentado así como los esfuerzos de todas aquellas personas y organizaciones que la promovieron. Este reconocimiento del Estado colombiano se hace con las salvedades expresadas en su oportunidad.

- El Gobierno Nacional, en su espíritu constructivo, invita a continuar fortaleciendo la relación con las comunidades indígenas y a encontrar fórmulas que garanticen la convivencia armónica entre los pueblos indígenas y el resto de la población, a conciliar intereses y a descubrir la riqueza del pluralismo preservando el medio ambiente y el patrimonio cultural de nuestros ancestros para las futuras generaciones.

B. Text analysis

The main claim of this unilateral declaration is to acknowledge official endorsement to the text of the UN Declaration. Some of the grounds of argumentation will be analyzed below. In accordance with the seven-step model for argument analysis, delivered by Scriven,19 I will clarify some meanings of specific terms, as well as identify the stated and unstated conclusions, the stated and unstated assumptions and an overall evaluation of the discourse.

C. Overall evaluation of the discourse

It is noteworthy to study the "discursive move" of the Colombian Government throughout the process of the adoption of the text of the UN Declaration. Whereas in the vote explanation of the abstention the Government made it clear that there are "insolvable contradictions" between the text of the Declaration and the National Legal System, in this occasion it praised the historic significance of this text, and even committed itself to "adhere" to its main values and principles. Once again, the Government acknowledged the massive support it has provided for the Indigenous Peoples through a significant set of policies, laws and ratified treaties aimed at respecting, protecting and fulfilling indigenous rights. Furthermore, the Government pointed out the cardinal importance of the principle of meaningful participation of the Indigenous Peoples in the decisions that concern the maintenance of their identity and culture. Nevertheless, it must not be forgotten the fact that the Government refers to the reservations it had posed in 2007 before the UN General Assembly when it abstained from voting the text of the Declaration.

The value added of this unilateral declaration of support, though not representing a legally binding manifestation, is meant to be its political strength in terms of willingness to "recognizing the historic importance" of the Declaration, and the "efforts of all the people(s) and organizations who promoted it". It might mean just rhetoric but the political meaning of this recognition must be considered.

CONCLUSIONS

According to Gasper,20 "all policy writing, considered as text and subtext, is open-able to various interpretations, some of them conflicting". In fact, as abovementioned, there are several terms which, for their vagueness, are indeed open to discussion, i.e. "general interest", "participation", "development", "economic independence", "construction of mutual trust", "to support the underlying principles of equality, respect diversity, and non discrimination", among others; especially, the prevalence of the argument that "Colombia is a multi-cultural and multi-ethnic State".

It is noteworthy that the Declaration was voted within the UN General Assembly on September 13th, 2007. While Colombia abstained from voting in the very session of the adoption of the final text, the unilateral declaration of 2009 does not constitute retroactive effects. In fact, since this Declaration is based on a resolution from the General Assembly, it is not legally binding as other international instruments such as treaties, covenants, among others. Therefore, the Declaration cannot be subscribed nor accessed by the states.

Although the UN Declaration constitutes a not legally binding document, these documents usually take the form of a (legally binding) treaty in the near future. One might guess that this would be the case of this instrument. In fact, this is precisely part of the socio-political struggle initiated some decades ago not only by the very Indigenous Peoples but by their political allies, namely, social movements, NGOs, and some progressive governments.

On the other hand, even though the Colombian Government was quite clear on the fact that there are several clauses of the UN Declaration which clash with the Internal Legal System of the State, the explicit and official endorsement to this instrument is a signal of its formal compromise with its contents and main goals. As with most of the international instruments that are not legally binding, the contents of these texts are entirely political. And this is not a minor issue. Koskenniemi21 states that "our inherited ideal of a World Order based on the Rule of Law thinly hides for sight the fact that social conflict must still be solved by political means and that even though there may exist a common legal rhetoric among international lawyers, the rhetoric must, for reasons internal to the ideal itself, rely on essentially contested political principles to justify outcomes to international disputes".

Foot notes

1Des Gasper, Introduction: Discourse Analysis and Policy Discourse, in Arguing Development Policy: Frames and Discourses, 1-15 (Raymond Apthorpe & Des Gasper, eds., Frank Cass, London, 1996).2Des Gasper, Introduction: Discourse Analysis and Policy Discourse, in Arguing Development Policy: Frames and Discourses, 1-15 (Raymond Apthorpe & Des Gasper, eds., Frank Cass, London, 1996).

3Des Gasper, Introduction: Discourse Analysis and Policy Discourse, in Arguing Development Policy: Frames and Discourses, 6 (Raymond Apthorpe & Des Gasper, eds., Frank Cass, London, 1996).

4Des Gasper, Introduction: Discourse Analysis and Policy Discourse, in Arguing Development Policy: Frames and Discourses, 1-15 (Raymond Apthorpe and Des Gasper, eds., Frank Cass, London, 1996).

5Des Gasper, Structures and Meanings - A Way to Introduce Argumentation Analysis in Policy Studies Education (Institute of Social Studies, ISS, The Hague, ISS Working Paper 317, 2000).

6International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, http://www.iwgia.org/sw248.asp (consulted on February 25th, 2009).

7International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, http://www.iwgia.org/sw248.asp (consulted on February 25th, 2009).

8Des Gasper, Structures and Meanings -A Way to Introduce Argumentation Analysis in Policy Studies Education (Institute of Social Studies, ISS, The Hague, ISS Working Paper 317, 2000).

9United Nations General Assembly, 61st session, September 13th, 2007, resolution A/61/ PV.107.

10United Nations General Assembly, 61st session, September 13th, 2007, resolution A/61/ PV.107.

11Des Gasper, Structures and Meanings - A Way to Introduce Argumentation Analysis in Policy Studies Education (Institute of Social Studies, ISS, The Hague, ISS Working Paper 317, 2000).

12Michael Scriven, Foundations of Argument Analysis, Reasoning, 40-45 (McGraw-Hill, New York, 1976).

13A clarification needs to be made in this point, since this is not itself the reason why Colombia abstained.

14In a country that surmounts an armed conflict, the presence of the military could paradoxically endanger the indigenous integrity rather than protecting it.

15Again, it is important to stress that this point of the lack of consensus is only a cover for the other issues.

16So far, this information can only be obtained in its original Spanish language version at: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Colombia, http://www.cancilleria.gov.co/wps/portal/ espanol/!ut/p/c1/04_SB8K8xLLM9MSSzPy8xBz9CP0os3gLUzfLUH9DYwN3d39zAyM3i1CjkEAnLwNnI6B8pFl8aFhQmFGwi7GBv2- QqYFRmI9ZoJersZGBpxkB3X4ebmp-gW5EeUAruoufg!!/dl2/d1/L2dJQSEvUUt3QS9ZQnB3LzZfVVZSVjJTRDMwT zA4RjBJMEc1TVNSRzI0SjY!/?WCM_GLOBAL_CONTEXT=/wps/wcm/connect/WCM_PRENSA/prensa/boletines/gobierno+de+colombia+anuncia+respaldo+unilate ral+a+la+declaracion+de++naciones+unidas+sobre+los+derechos+de+los+pueblos+indigenas (last accessed September 5th, 2009). The English version of this text could not be obtained by the time of the submission of this article.

17United Nations official webpage, http://www.un.org/durbanreview2009/index.shtml (last accessed September 5th, 2009).

18This text could only be obtained in its original Spanish language so all the translations made throughout this section were elaborated by the author.

19Michael Scriven, Foundations of Argument Analysis, Reasoning, 40-45 (McGraw-Hill, New York, 1976).

20Des Gasper, Introduction: Discourse Analysis and Policy Discourse, in Arguing Development Policy: Frames and Discourses, 1-15 (Raymond Apthorpe & Des Gasper, eds., Frank Cass, London, 1996).

21Martii Koskenniemi, The Politics of International Law, 1 European Journal of International Law, EJIL, 1, 4-32 (1990).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BOOKS

Scriven, Michael, Foundations of Argument Analysis, Reasoning (McGraw- Hill, New York, 1976). [ Links ]

CONTRIBUTION IN COLLECTIVE BOOKS

Gasper, Des, Introduction: Discourse Analysis and Policy Discourse, in Arguing Development Policy: Frames and Discourses (Raymond Apthorpe & Des Gasper, eds., Frank Cass, London, 1996). [ Links ]

JOURNALS

Koskenniemi, Martii, The Politics of International Law, 1 European Journal of International Law, EJIL, 1, 4-32 (1990). [ Links ]

WORKING PAPERS

Gasper, Des, Structures and Meanings - A Way to Introduce Argumentation Analysis in Policy Studies Education (Institute of Social Studies, ISS, The Hague, ISS Working Paper 317, 2000). [ Links ]

WEBSITE LINKS

United Nations website: http://www.un.org. [ Links ]

On the Durban Review Conference: at http://www.un.org/durbanreview2009/index.shtml. [ Links ]

International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs- IWGIA official webpage: http://www.iwgia.org/sw248.asp. [ Links ]

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Colombia on the endorsement of the UN Declaration: http://www.cancilleria.gov.co/wps/portal/espanol/!ut/p/ c1/04_SB8K8xLLM9MSSzPy8xBz9CP0os3gLUzfLUH9DYwN-3d39zAyM3i1CjkEAnLwNnI6B8pFl8aFhQmFGwi7GBv2-QqYFRmI- 9ZoJersZGBpxkB3X4e-bmp-gW5EeUAruoufg!!/dl2/d1/L2dJQSEvUUt3QS9ZQnB3LzZfVVZSVjJTRDMwTzA4RjBJMEc1TVNSRzI0SjY!/ ?WCM_GLOBAL_CONTEXT=/wps/wcm/connect/WCM_PRENSA/prensa/boletines/gobierno+de+colombia+anuncia+respaldo+unilater al+a+la+declaracion+de++naciones+unidas+sobre+los+derechos+de+los+pueblos+indigenas. [ Links ]