Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

International Law

versión impresa ISSN 1692-8156

Int. Law: Rev. Colomb. Derecho Int. n.16 Bogotá ene./jun. 2010

YOU'D BETTER LISTEN: NOTES ON THE MAINSTREAMING OF PUBLIC PARTICIPATION IN FOREIGN INVESTMENT ARBITRATION*

MEJOR PONER ATENCIÓN: APUNTES SOBRE EL SIGNIFICADO DE LA PARTICIPACIÓN CIUDADANA EN EL ARBITRAJE INTERNACIONAL DE INVERSIÓN

René Urueña**

* Artículo de investigación culminado dentro de las labores del autor en la Universidad de los Andes, sin financiación externa.

** Professor of International Law and Director of the International Law Area, Universidad de los Andes (Bogotá, Colombia). Research Fellow, Centre of Excellence in Global Governance Research, University of Helsinki, Finland.

Contact: rf.uruena21@uniandes.edu.co.

Reception date: February 1st, 2010 Acceptance date: May 20th, 2010

TO CITE THIS ARTICLE / PARA CITAR ESTE ARTÍCULO

René Urueña, You'd better listen: Notes on the Mainstreaming of Public Participation in Foreign Investment Arbitration, 16 International Law, Revista Colombiana de Derecho Internacional, 293-346 (2010).

ABSTRACT

This paper explores the rhetoric surrounding Non Governmental Organizations, NGOs, participation in the context of foreign investment arbitration. It argues that public participation is a crucial part of the investment arbitration mindset, not in a subsidiary role or as a mere legitimating devise, but as an expression of a substantial world view -which I call here the "public interest narrative" in foreign investment arbitration. The argument, though, is not normative, but rather seeks to show that, far from being a mere goal, this "public interest narrative" is a central aspect of investment arbitration today. To make this point, the paper explores three iconic cases: Methanex (under NAFTA/UNCITRAL), Aguas de Tunari (ICSID), and Biwater (the first case tried in its entirety under ICSID's Rule 37). The paper concludes that scholars and practitioners working in foreign investment law would be well advised in going beyond the view that participation in arbitral procedures is a contentious issue pushed by some activists in Geneva or Washington D.C. Participation is here to stay, and seems to be affecting, in very crucial ways, the substantive (and financial) outcome of arbitral procedures.

Key words author: Foreign Investment Arbitration, Participation, Transparency, NGOs, International Law, Globalization.

Key words plus: Non-Governmental Organizations, Commercial Arbitration, International Law.

RESUMEN

Este artículo explora la retórica que rodea la participación de organizaciones no gubernamentales, ONG, en el arbitraje internacional de inversión. Argumenta que la participación ciudadana es un elemento crucial del arbitraje, no en un rol subsidiario o como simple mecanismo de legitimación, sino como una expresión de una visión sustantiva del mundo, denominada aquí la "narrativa del interés público" en el arbitraje internacional de inversión. El argumento aquí presentado no es normativo; por el contrario, busca mostrar que hoy, lejos de ser un simple objetivo deseado, la "narrativa de interés público" es un aspecto central en el procedimiento arbitral. Para probar tal punto, se exploran tres casos ícono: Methanex (bajo TLCAN-UNCITRAL), Aguas de Tunari (CIADI) y Biwater (el primer caso decidido en su totalidad bajo la Regla 37 de CIADI). A partir de este análisis, el artículo concluye que académicos y practicantes que trabajen en arbitraje internacional de inversión harían bien en ir más allá de la percepción, según la cual la participación ciudadana es una idea controversial defendida por unos activistas en Ginebra o en Washington D.C. La participación está aquí para quedarse y parece estar afectando, de manera muy importante, el resultado sustancial (y financiero) de los arbitrajes.

Palabras clave autor: arbitraje de inversión, participación, transparencia, ONG, derecho internacional, globalización.

Palabras clave descriptor: Organizaciones no gubernamentales, arbitramento comercial, derecho internacional.

SUMMARY

INTRODUCTION.- I. HOW TO START THINKING ABOUT GLOBAL POLITICAL PARTICIPATION?- A. One common prescription.- B. Citizenship and administrative participation.- C. The purposes and benefits of participation.- D. Participation as an expression of legitimacy: the "public interest narrative."- II. PARTICIPATION, THE PUBLIC INTEREST NARRATIVE, AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT ARBITRATION.- A. Context and importance of foreign investment arbitration.- B. Participation in foreign investment arbitration.- 1. NAFTA.- 2. ICSID.- C. Participation and the 'public interest' narrative in ICSID arbitration.- III. PARTICIPATION AND THE 'PUBLIC INTEREST' NARRATIVE IN ICSID ARBITARTION.- CNCLUSION.- BIBLIOGRAPHY.

INTRODUCTION

This paper explores the rhetoric surrounding NGO participation in the context of foreign investment arbitration. It argues that public participation has become a central tenet of investment litigation, and should be considered as an important variable when designing litigation strategies. Departing from most of the existing literature on the subject, though, the argument in this paper is not normative. It is not my intention to argue that participation should become a central aspect in the procedure of investment litigation, based some combination of global constitutional values such as democracy, transparency -what have you.1 Rather, I seek to show how participation is a crucial part of the investment arbitration mindset, not in a subsidiary role or as a mere legitimating devise, but as an expression of a substantial world view -which I call here the "public interest narrative" in foreign investment arbitration. Scholars and practitioners working in foreign investment law would be, thus, well advised in going beyond the view that participation in arbitral procedures is a contentious issue pushed by some activists in Geneva or Washington D.C. NGO participation seems to be here to stay.

The argument is divided in two parts and five sections. Part I explores the problem of participation in global governance, whereas Part II zeroes in on the issue of NGO participation in foreign investment arbitration. Part I is composed of three sections: The first presents the problem of disregard, and explores the conceptual background necessary to understand the rhetoric of participation in global governance; the second ponders the relation between citizenship and administrative participation; and the third explores purposes and benefits of participation in the global political process. Part II, in turn, is composed of two sections: the first introduces Context and importance of foreign investment arbitration; the second explores participation in foreign investment arbitration, and features two case studies: the North American Free Trade Agreement, NAFTA and the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes, ICSID, verifying in each case the role played by the "public interest narrative." Each of these cases has inspired novel developments in the area, and provides insight not only to the formal legal discussions concerning participation, but also to the interests of the different actors behind such discussions. For this reason, we shall engage in some detail with each case, describing thoroughly the political context and consequences of each decision. The methodology, thus, is less a top down analysis than a bottom up approach to the issues at hand. Finally, some conclusions are drawn.

I. HOW TO START THINKING ABOUT GLOBAL POLITICAL PARTICIPATION?

A. One common prescription

In order to think about global political participation, a useful point of departure is the problem of disregard; that is, the fear that the recent redistribution of power has allowed global regulatory bodies to "disregard or give inadequate consideration to developing country or small states, to vulnerable groups such as indigenous peoples, or to diffuse societal interests and values impacted by their decisions."2 When faced with such problem, lawyers and political scientist will often mention participation and enhanced accountability as the two main poles around which solutions will cluster.3 My focus here is on participation; i.e, the ability of those potentially affected by a decision to make their voice heard before such decision is taken.4 The relation between disregard and participation is often conceptualized in the form of three archetypical critiques: (a) Limited participation; (b) Inappropriate participation; and, (c) 'Misplaced' participation. Let us briefly consider each of them:

- Limited participation : According the first archetype of critique, there is disregard because there is not enough participation -that is, institutions are closed to voices different from their formal membership. As we will see below in extenso, the World Trade Organization (WTO) is often subject to this critique.

- Inappropriate participation : According the second archetype of critique, the problem of disregard exists because available participation is ill conceived -that is, institutions are indeed open, but they are open to the wrong interests. This charge, that shares some features with regulatory capture,5 is exemplified by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. The Committee is a forum for cooperation on banking supervisory matters that emerged as a reaction to the 1974 Herstatt Bank failure in Germany. It is composed by senior officials of central banks and financial regulators from the G10 (Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States), plus Luxembourg and the State of New York. It establishes standards on capital adequacy and other financial matter that, although not technically binding, are 'voluntarily' adopted by almost all financial institutions in the world. Until now, two comprehensive sets of standards have been adopted: Basel I (1988) and Basel II (2004). Criticism appears as very few States are represented in a regulatory network that affects most States of the world.6

- Misplaced participation : Finally, the third archetype of critique holds that global institutions disregard important interests because they are relatively closed -that is, given a redistribution of power, the global regulatory body is deemed too closed as compared to the domestic agency that used to (or would) take an equivalent decision, for example, the Codex Alimentarius Commission, CAC. The Codex Alimentarius is a set of norms that provides standards of food quality. The governing body of the Codex is the Codex Alimentarius Commission, which features an Executive Committee, seven Commodity Committees, and nine General Subject Committees, composed all of government representatives from most countries of the world.7 The Commission often includes significant participation by NGOs and, going beyond mere observer status, the Codex Procedural Manual recognizes a private industrial organization (the International Dairy Federation) as responsible for providing first drafts of Codex standards for the Committee on Milk and Milk Products.8

The Codex is of great importance, and made even more relevant because Article 3 of the World Trade Organization (WTO) Sanitary and Phytosanitary Agreement (SPS) provides that domestic food regulations that conform to international standards are presumed to be in compliance with that Agreement and General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, GATT; in contrast, members that depart from international standards must provide scientific justification to do so. Section 3(a) of Annex A of the SPS Agreement, in turn, defines international standards for food safety as those established in the Codex Alimentarius, among others. What this means, in practice, is that member States of the WTO who comply with the (voluntary) standards of the Codex are presumed to comply with the (mandatory) dispositions of the SPS Agreement and the GATT. Therefore, States have an important incentive to follow the Codex: although remaining formally voluntary, adopting the Codex does reduce the risk of WTO litigation. Criticism appears as food safety standards under domestic jurisdictions are often subject to procedural requirements that would ensure their quality, including participation. That is not the case with the Codex.9

These three critiques have one proposal in common. If faced with the problem of disregard, activists, lawyers and political scientists often conclude with a variation of the same normative proposal: reform of procedural norms, seeking to 'open' spaces for participation in global governance. The following section unpacks such prescription.

B. Citizenship and administrative participation

Even if restricting the discussion to 'participation', it is useful to define first the kind of interaction that is understood as such. Political participation can be understood quite widely, and include in the notion manifestations of citizenship such as voting, or running for public office. In this wider sense, participation is closely connected with the idea of citizenship.10 It is important, though, to draw a line between these two notions, as the construct of citizenship may be misleading to understand the global dimension of political participation, as it is a wide concept that entails several different meanings at the domestic level, making it hard to use it a standard for analyzing global governance. Indeed, citizenship refers, firstly, to a sociological problem, which relates to the de facto linkage between individuals (citizens) and a specific community.11 Moreover, it refers to a legal matter, which concerns relation between said individuals (citizens) and the State. This second conception is composed, in turn, of two different problems: first, the idea of a downward (State to individual) recognition of citizens. In this sense, as Chief Justice Earl Warren of the US Supreme Court of Justice [October 2, 1953-June 23, 1969] has put it, 'citizenship is man's basic right, for it is nothing less than the right to have rights.'12 In this sense, the legal account of citizenship is either a history of regulatory measures of naturalization,13 or a historically determined evolution of rights of the citizen: civil rights led the way to social rights, which opened the door to economical rights.14 Symmetry demands an 'upward' for all 'downward' ideas: in this case the complementary aspect of citizenship as a legal matter describes the relation from the individual to State. In this latter sense, citizenship describes the relation whereby 'citizens' are deemed as sovereign and consent to be ruled by the state. As sovereign citizens accept limits to their natural autonomy, they 'create' legitimate state power. Non citizens have not that power in their hands. Only citizens who consent may legitimize power.

As we can see, citizenship describes phenomena occurring at the domestic level that widely differs from each other -limiting thus its use as a conceptual tool to understand global governance. This limitation is made more serious by the fact that citizenship is a surprisingly State -bound idea, as it relies heavily on the notion of allegiance, understood in the traditional account of citizenship as a concrete matter, insolvably related to the central role of the State.15 These limitations make citizenship bring more confusion than clarity to the debate on global political participation. Consequently, the notion to be used here is much narrower, and refers to the interaction between private actors and regulatory agencies. A fundamental criteria, though, is lack of formal decision-making power by those who participate (in the form of votes, power of veto, etc). Participation in the sense used implies that the regulatory agency takes the ultimate decision, and private actors are allowed to use 'participatory mechanisms', which typically include:

- The possibility to intervene in a procedure initiated by others. This intervention may take the form of submission of evidence or arguments to the regulatory agency, attendance to meetings or hearings organized with occasion of the procedure and, finally, the intervention in consultations or 'notice and comment' procedures initialized by the regulatory agency.

-

The possibility of initiate an administrative procedure. Here, the problem of participation tends to merge with the debate on standing and the problem of legal interest in the procedures.16 And yet, for the purposes of this section, and in order to start thinking about global participation, it seems useful to bracket the issue of global legal standing for the time being.

C. The purposes and benefits of participation

A good way to start thinking about participation is to consider it in the more or less familiar environment of domestic politics. In this context, participation is often mixed with a general analysis of democratic good governance.17 In order to start thinking about participation, though, it seems useful to draw a line between it and democracy. Even though both concepts are intuitively connected to the same cluster of ideas, it is possible to argue that a claim for participation is not necessarily related to a claim to democracy. To be sure, participation may be conducive to a more democratic system, and democratic regimes are often participatory. And yet, as Hannah Arendt has noted, mass participation can actually create the preconditions of totalitarism, through isolation and loneliness.18 It seems, thus, methodologically useful to consider the participatory layout of institutions as neither necessary nor sufficient for a democratic regime. Think of a decision to prohibit the import of beef treated with hormones. It seems irrelevant if the agency that will adopt the ban is, for example, part of a democratically elected government or part of a dictatorship. As far as both open procedures similar to those described in Section II, they can be usefully compared.

Now: what, if not promoting democracy, is a stake in the use of participation? It is possible to group justifications for participation in three different categories: quality of the decision, positive externalities, and legitimacy. Let us now consider each of them. First, participation improves the quality of a decision.19 Thus, in our example, scientists, industry, academics, etc, could appear before the agency, providing their arguments for or against the ban. The agency, in turn, has more and better information at its disposal, and takes a better decision. Yet, the causal relation between participation and quality of decisions should not be taken at face value, for it can be unpacked in revealing ways. It seems to refer not to how 'good' a decision to its addressees -after all, regulatory decisions have winners and losers, and the 'good' decision of the former will most likely be a 'bad' decision for the latter. Rather, it refers to the technical quality of the decision: how much of a given expertise is revealed by the decision. In our example, whether the correct risk assessments were considered, whether appropriate scientific evidence was provided, etc.20 This is revealing: while it is certain that participation helps reduce asymmetries of information between regulator and citizens, the 'quality' argument seems to have two different effects: one, it seems to reduce participation to a scanty mechanism of data gathering. If only the agency would have enough staff, participation would be unnecessary. And second, it transfers power towards the 'experts', thus placing a premium on 'skilled' participation. All participation is equal, but in this context some participants are more equal than others.21

A second group of arguments suggest that participation produces positive externalities in the form of enhanced transparency, such as better accountability, easier control by other branches of government and preventing the risk of regulatory capture, all of which are enforced by, importantly, making judicial review easier.22 In our example, the access to information implicit in the participatory process would allow Congress to perform and informed assessment of the agency's decision, holding public servants accountable if that is the case. The same can be said of media control and, to be sure, potential judicial review of the ban, which is made easier by the paper trail left in the participatory process. Once again, it is clear that access to documents and reason giving involved in collaborative participation makes it easier to assign responsibilities and implement control. Yet, although welcome byproducts, these are not the main motivations behind participation: there seem to be more efficient ways of achieving that goal -most importantly, procedures establishing free access to information. Consider in our example that the problem to be solved is, indeed, enhanced accountability of those deciding the ban, or improving transparency of the process, or even facilitating judicial control. Public participation hardly sounds as the way to achieve those ends.

D. Participation as an expression of legitimacy: The "Public Interest Narrative"

Participation seems to find its ultimate justification, then, in the idea that it lends legitimacy to the institution taking the decision. Legitimacy is not an easy concept to work with, as it has been criticized as an empty academic formula, devised to avoid normative substance while giving the semblance of substance.23 However, it does offer some added value as an analytical category, as Thomas Franck has shown. Franck rejects the idea that international relations are reduced to the States interacting as individual actors,24 and rather puts forward the idea of a community.25 It is only in reference to a community (and not to a group of benefit maximizing actors) that Franck's argument on legitimacy rings plausible: some years later, in Fairness in International Law and Institutions, he would even draw a parallel between contractualist theories of the State and the origins of the international legal order.26 Legitimacy and community imply each other; in Franck's words: '[i]f legitimacy validates community, community must be present for legitimacy to have content.'27

The sensitivity that there is something out there in the global community, beyond the mere multilateral interest of the immediate parties, is what I shall call here the "Public Interest Narrative." This narrative is not a theory, or a substantive agenda for redistribution in global governance (yet it may very well imply both). And it is certainly not a body of international legal rules or principles. Instead, it is a professional sensitivity, a langue, which in turn defines the border of possibilities in arguments in international law.28 Participation is an expression of the public interest narrative in international law. The underlying understanding that there is community beyond the immediate discussion at hand warrants the need to include other voices, different from those of the immediate parties. As a consequence, the public interest narrative is determined by the notion of community that underlies it - a notion that is hardly univocal.

What about the domestic setting? The notion of 'community' is not necessary in that context. As a result, there is no public interest narrative, at least of the sort being argued here. Participation in the domestic context is a mere proxy for consent, which is in turn part of a wider debate that concerns the existence of the State, or of a given governmental layout. For example, a contractualist view of the State would hold consent quite dear, while a theocratic justification of the State would doubt of its importance. This debate, though, is beyond the point treated here: even if consent is indeed deemed of importance, participation is not the main mechanism to achieve it in global governance. To this effect, the whole apparatus of popular will enters into the equation, as a form of justifying public power. In contrast, participation seems to play a rather subsidiary role. It is, at best, instrumental for the achievement of positive externalities -but not necessary for that purpose. Now, this poses no fundamental problem in domestic politics, for participation seems like a bonus in that context: public participation is not expected to provide the rationale justifying public power, but is rather the cherry on top of the pie. On top of having a democratic (or charismatic, or technocratic) regime, which is justified on its own terms, we have spaces of public participation.

II. PARTICIPATION, THE PUBLIC INTEREST NARRATIVE, AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT ARBITRATION

Part I of this paper presented a general theoretical framework to understand participation in global governance. It analyzed its benefits and underlying agendas, and proposed the "Public Interest Narrative" as an alternative category, instrumental to understand the dynamics of global political participation. Part II of this paper shall apply that category to arbitration in foreign investment law. As was stated in the introduction, the argument in this Part is not normative. It is not my intention to argue that participation should become a central aspect in the procedure of investment litigation, based some combination of global constitutional values such as democracy, transparency -what have you. Rather, I seek to show how participation is a crucial part of the investment arbitration mindset, not in a subsidiary role or as a mere legitimating devise, but as an expression "public interest narrative" in foreign investment arbitration. But, before we go there, let us get to know better the context and importance of foreign investment arbitration.

A. Context and importance of foreign investment arbitration

In order to grasp the stakes behind participation in foreign investment arbitration, we need to understand first the important change implicit in such type of international adjudication. International investment agreements (IIAs) may be the single most important factor transforming the global economic landscape today. A tightly-knit net of almost 5500 IIAs covers the planet,29 crucially influencing decisions with a potential impact in sustainable development. However, despite their great importance, the specific scope and risks of this phenomenon seem to be hardly grasped by governments and the general public. One reason for this is the decentralized nature of the current IIA wave. Unlike work at institutions like the WTO or the World Bank, investment deals are commonly stricken on a bilateral basis:30 there is no single decision-making centre to follow. Moreover, a considerable part of international investment regulation is developed through arbitration awards; consequently, important legal principles have to be inferred from bits and pieces of awards that are, in any case, adopted under a veil of secrecy. There is no one decision or instrument that can be singled out as the cause of change. And yet, a general change is indeed taking place.

As hinted by their name, an IIA is an agreement between two or more States setting down rules that govern investments by their respective nationals in the other's territory. IIAs are not overviewed by a single treaty organ, and come in different forms and shapes. The most common presentation is the Bilateral Investment Treaty, BIT, such as that concluded between the US and Singapore,31 which is a self-standing instrument dealing integrally with investment. Furthermore, IIAs are also included as 'investment chapters' in free trade agreements - NAFTA's Chapter 11 being the most well known of them all.

IIAs are most often concluded between a developed and a developing country, yet so-called 'South-South' agreements are increasingly common.32 'North-North' agreements, in turn, are extremely rare: according to UNCTAD, only eleven have been concluded.33 Reasons why developing countries enter IIAs are manifold. To be sure, the most important one is the belief that the agreements will foster direct foreign investment (FDI), which will in turn bring development and general prosperity. Such premise has drawn considerable fire from different fronts, as studies by the UN, the World Bank and other independent experts have concluded that there is no compelling evidence showing that IIAs actually stimulate FDI.34 Rather than encouraging greater FDI in developing countries, IIAs seem to only have a positive effect on FDI flows in countries with an already stable business environment.35 Thus, the benefit form concluding the agreement for the host country would ultimately null. Notwithstanding this, IIA continue being concluded by dozens -a paradox that is perhaps better explained by heavy-handed politics and strategic geopolitics, than by the economic benefits of the agreement in and of itself.36

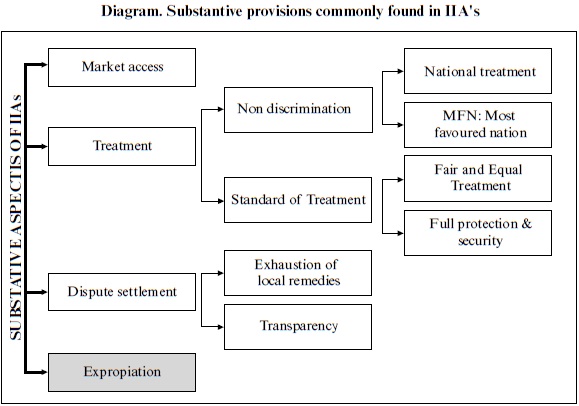

Substantively, the standard IIA provides investors with protection in four areas: market access, treatment, expropriation, and dispute settlement. Market access assures investors the opportunity of participating in the market of the other party. Such assurance, in turn, would be irrelevant if investors could be discriminated or ill-treated by host States. Therefore, the second substantive provision often included in IIAs relates to, on one hand, non-discrimination provisions (e.g., national and most-favored-nation treatment), and a minimal standard of treatment for foreign investor in the host State, on the other (usually, fair and equitable treatment and full protection and security).37 Thirdly, most IIA's include astringent provisions regarding expropriation, which have stirred considerable debate for the so-called regulatory chill effect they entail.38 These standards are enforced through exceptional mechanisms of adjudication, which form the fourth pillar of a most IIAs -dispute settlement. Investment agreements usually give jurisdiction to arbitration tribunals over disputes between private investors and the Host State, giving private parties right of standing before such international tribunals, often allowing the investor to choose between exhausting domestic remedies and recurring directly to the international jurisdiction.39 The combination of these four pillars makes investment arbitration a controversial formula of global governance.40

Substantive provisions commonly provided in IIAs

B. Participation in foreign investment arbitration

As we saw, IIAs impose certain obligations on host States with regards to foreign investors acting under their jurisdiction. These obligations are, in turn, often subject to adjudication in the form of arbitration, whose procedural rules set the background for discussing spaces of participation in this form of global power. There are two main groups of rules applicable to such procedures: ICSID and UNCITRAL. In turn, NAFTA features an interesting application of such rules in the North American context, which will be also enlightening for the purpose of understanding the stakes of participation in foreign investment arbitration. In what follows, we will briefly discuss each of them, having an eye in their respective interaction with global political participation.

1. NAFTA

Let us begin by the NAFTA experience. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) is a trading block that entered into force the 1st of January 1994, and seeks to integrate the markets of Mexico, the United States, and Canada. As any of such agreements, NAFTA is complex and features several controversial aspects.41 Of special interest in our case is NAFTA's Chapter 11. Under that Chapter, parties to the Agreement undertake to treat investors from other parties in accordance to the standards put forward in the Chapter. To that effect, NAFTA features, in broad terms, the same characteristics as most others IIA's: market access, treatment, expropriation, and dispute settlement. The standards of treatment, in turn, are also common: national treatment (Article 1102), most favoured nation, MFN (Article 1102), fair and equitable treatment, and full protection and security (Article 1105), among others. Expropriation is defined as to include the possibility of indirect or regulatory measures (Article 1110), and dispute settlement (Article 1115-1138).

NAFTA meant a fundamental break with prior foreign investment law, at least in two accounts: first, it was by far the farthest reaching system of investor rights put forward until that moment. And second, it was the first multilateral treaty to provide individuals (and, to be sure, corporations) with direct access to international adjudication on investment disputes. Later, would come the 1994 Energy Charter Treaty (entered into force in 1998),42 MERCOSUR's Protocolo de Colonia para Promoción y Protección Recíproca de Inversiones (1994),43 and the investment provisions of the so-called '1994 Grupo de los Tres' (Colombia, Mexico and Venezuela -entered into force in 1995).44 And yet, despite its novelty, NAFTA does not create a new set of procedural rules in dispute settlement. Rather, Article 1120 (1) gives the disputing investor the option of choosing among two sets of rules: (a) the ICSID Convention, provided that both the disputing Party and the Party of the investor are parties to the Convention; and, (b) the Additional Facility Rules of ICSID, provided that either the disputing Party or the Party of the investor, but not both, is a party to the ICSID Convention. However, NAFTA's interest to us lies not there, but in the controversies that surrounded the application of such procedural rules with regard to the participation of non-parties in investment arbitration. Even though there was no innovation in the text provided by the agreement, NAFTA is the first case where amicus curiae ('friend of the court') briefs were proposed and actually accepted by an investment tribunal. Originally incorporated in common law systems, amici briefs are, in essence, memorials submitted to the court by someone that is not a party to the conflict, but who volunteers an opinion under the belief that it will help the court adopt a better decision.45

The case in point is Methanex.46 This case relates to Methyl tertiary-butyl ether (MTBE), a substance used in gasoline as a source of octane and as oxygenate.47 Methanex, a Canadian corporation, owned Methanex Methanol Co., an American company that manufactured and sold methanol, which is used to produce MTBE. California is an important market for methanol -its use of MTBE amounts to about 6% of the global market. In 1999, the Governor of California ordered the Energy Commission in that state to develop a timetable for the removal of MTBE no later than December 2002, arguing that 'on balance, there is significant risk to the environment from using MTBE in gasoline in California'.48 The decision was based on a California Senate funded study, conducted by the University of California.49 Furthermore, United States Environmental Protection Agency, US EPA, had classified MTBE as a known animal, and possibly human, carcinogen.50 Reacting to the decision, Methanex filed for NAFTA arbitration under UNCITRAL rules in July 1999, after the Governor's order, but prior to its implementation.51 In July 2001, Methanex amended its application to include the charge of corruption, presenting new information to the effect that Archer-Daniels-Midland Co., the principal US producer of ethanol (methanol's main competitor), had allegedly influenced the Governor's decision on MTBE through campaign contributions.52

The Methanex dispute clearly featured issues that involved the interest of a wider audience, especially those interested in energy and the environment. Two amici submissions for amici standing were presented,53 which were followed by a Supplemental Application and a Final Submission by the petitioners.54 The investor opposed the amici petition, arguing that the submission would contravene the confidential nature of the procedures, would expand the notion of party in a manner contrary to the text of Chapter 11, and would therefore fall outside the competence of the Tribunal.55 The United States, as respondent, supported the petitioners and argued that nothing prevented the Tribunal from considering submissions for leave to make amicus submissions.56 Mexico and Canada were also asked their opinion on the matter. Canada agreed with the US, expressing that, though mindful of the confidentiality demanded by the procedures, nothing in the NAFTA or the UNCITRAL prevented the Tribunal to accept the submissions.57 Mexico, in turn, rejected such an argument: the Tribunal has only competence to seek advice or additional information from 'expert witnesses', a label that ill fits the petitioners. Furthermore, Mexico argued, amici curiae are a paradigmatic common law institution, wholly foreign to the Mexican civil law system. Accepting amici submissions would, in their opinion, disrupt the balance between common law and civil law procedures achieved in the text of NAFTA.58

The core of the discussion was Rule 15 of the 1976 UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules. Under that Rule,

- [...] the arbitral tribunal may conduct the arbitration in such manner as it considers appropriate, provided that the parties are treated with equality and that at any stage of the proceedings each party is given a full opportunity of presenting his case [...].

The question was, then, whether admitting amici submissions would fall under such competence. The Tribunal decided it did.59 For the first time in an investor-State arbitration, the Tribunal held that it had the authority to admit the submissions, as Rule 15 (the 'procedural Magna Carta of international commercial arbitration', in the Tribunal's words)60 does provide it with a wide power to adopt the measures it deemed necessary to conduct the procedures. And why was it necessary in the Methanex case? For the Tribunal,

- There is undoubtedly public interest in this arbitration. The substantive issues extend far beyond those raised by the usual transnational arbitration between commercial parties. This is not merely because one of the Disputing Parties is a State; there are of course disputes involving States which are of no greater public importance than a dispute between private persons. The public interest in this arbitration arises from its subject matter, as powerfully suggested in the Petitions. There is also a broader argument, as suggested by the United States and Canada: the Chapter 11 arbitral process could benefit from being perceived as more open or transparent; or conversely be harmed if seen as unduly secretive. In this regard, the Tribunal's willingness to receive amicus submissions might support the process in general and this arbitration in particular; whereas a blanket refusal could do positive harm.61

It is hard to exaggerate the importance of this line of argument. The Tribunal understood the issue as a bilateral conflict, with public consequences. There is an underlying idea here that, despite the fact that the dispute is of commercial nature and involves only two parties, there are other issues at stake in the arbitration. Such other issues would provide the rationally for accepting the amicus in this, as the Tribunal indeed did. This mindset was then underscored by NAFTA's contraction parties, who adopted in July 2001 a set of 'Notes of Interpretation of Certain Chapter 11 Provisions', whose Section (1)(a) provides that:

- Nothing in the NAFTA imposes a general duty of confidentiality on the disputing parties to a Chapter Eleven arbitration, and, subject to the application of Article 1137(4), nothing in the NAFTA precludes the Parties from providing public access to documents submitted to, or issued by, a Chapter Eleven tribunal.62

This statement was complemented by a 2003 'Statement of the Free Trade Commission on non-disputing party participation', whose section A (1) held specifically that 'No provision of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) limits a Tribunal's discretion to accept written submissions from a person or entity that is not a disputing party (a "non-disputing party")', and put forward certain procedures to implement such possibility.63 Following such procedure, and after some dispute regarding the exact nature of the Tribunal's authorization,64 the first amicus curiae in an investor-State arbitration was submitted on March 2004 by the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), joined by the Bluewater Network, Communities for a Better Environment, and the Center for International Environmental Law.

Following the procedure provided in the Federal Trade Commission's (FTC) Statement, the defendant submitted in March 2004 that the Tribunal should grant the permission requested by the potential amici, and Methanex indicated that it did not object to the granting of such permission.65 The submissions tried to put forward three arguments, that can be broadly summarized thus: first, foreign investment law does not provide an 'insurance policy' against the usual risk faced by multinational corporations; second, foreign investment law does not impact host States' right to regulate; and, third, there is a difference between ethanol and methanol (there are not 'like products'), and thus can be regulated differently without violation of the national treatment clause in NAFTA.66 It should be noted, though, that Amici did not present a position against Methanex's argument of corruption, most probably due to limitations in access to final memorials submitted by the parties.The final award in Methanex is notable in that it went deeply into the issue of corruption. In that regard, the Tribunal established its own competence to address the issue, and adopted a self labeled 'connect the dots' methodology to perform the task. The dots in this case, though, did not lead to a finding of corruption.67 This move, in itself, is a novelty in investment law but, as we have seen, not a matter discussed by amici. On the issues that were discussed by the submissions, the Award is less bold, but still found strongly against the investor. National Treatment was decided on the basis of a narrow notion of likeness, which featured the rejection of a trade law (namely, WTO) inspired interpretation.68 As a result, the Tribunal held that the US had not discriminated against Methanex. The expropriation ruling is also quite favorable to the host State, and seems to follow the mindset proposed by amici.69 The award found that no expropriation had taken place in this case. It accepted that an intentionally discriminatory regulation against a foreign investor fulfils a key requirement for establishing expropriation. By the same token, a non-discriminatory measure would only be expropriatory if the government had committed to refrain from regulation. Such commitments, according to the Tribunal, can be expressly given by officials, or reasonably understood by the investor. Neither of them occurred in this case. For the Tribunal, Methanex entered an investment context that is well-known for its leadership in environmental issues; hence, regulation could be reasonably expected. Moreover, Methanex's charges of 'corruption' are read by the Tribunal as part of a general, foreseeable, political process that, in fact, also benefited Methanex. Consequently, the Tribunal found that measures in question were for a public purpose, non-discriminatory and accomplished with due process. The Tribunal finally assessed whether a lost customer base, goodwill and market share can be deemed 'investments' in the sense of Article 1110, and thus subject to expropriation. It agreed they could, but not alone-rather, as part of the valuation of the taking of an enterprise. In this case, no taking had taken place. Finally, and leaving no doubt as to who had prevailed in the arbitration, the Tribunal decided that Methanex had to bear all the costs of the procedures, and would have to pay US's legal costs (US$2,989,423.76) and its share of interim deposit for the costs of arbitration (US$1,071,539.21).70

The Methanex precedent and the 'Statement of the Free Trade Commission on non-disputing party participation' have since become the standard approach to participation in NAFTA investment arbitration, and have, in turn, influenced further developments of the area. The main lesson to be taken from here is the Tribunal's (and FTC's) implicit understanding of what was at stake in the problem of participation. For them, the dispute at hand represented a conflict between two parties with formal standing before the Tribunal. However, the subject matter of the controversy would call for an additional variable in the equation: while the parties are still masters of the controversy, this additional variable would explain that other voices are taken into account -in this case, those of the intervening NGOs. This is hardly a fully fledged theory put forward by the adjudicators, but is an actual departure from the strict view they try to pass as their argument, exclusively focused to the investor-State duet. I will not try to read more into this strategy than it actually allows. And still, even if one reads Methanex from a narrow point of view, the whole saga features an unmistakable understanding that the issue at hand is not exhausted in reference to the parties in the dispute. More is at stake -what, exactly, is never explained. Yet, what interests me here is the structure of such narrative: a narrative of public good, of public interests that are beyond the mere conflict of private actors, which informs and justifies the idea of participation. This narrative has proven present and controversial outside the NAFTA context, specifically in ICSID arbitrations, as we now turn to see.

2. ICSID

The International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) is an independent international organization that is a part of the World Bank Group, and was created by the Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes between States and Nationals of Other States 1965, entered into force in 1966 (the 'Convention'). Despite having more than 150 members,71 ICSID is a fairly small international organization, featuring only an Administrative Council and a Secretariat (Articles 4 to 11 of the Convention). ICSID's relevance lies, though, in its Dispute Settlement Facilities. Under Article 25 of the Convention, ICSID has jurisdiction over any legal dispute arising directly out of an investment, between a Contracting State and a national of another Contracting State, which the parties to the dispute consent in writing to submit to the Centre. Importantly, under the same provision, when the parties have given their consent, no party may withdraw its consent unilaterally.

ICSID provides two essential services: conciliation (Chapter III of the Convention) and arbitration (Chapter IV). These services are regulated by two sets of procedural norms: those included in the Convention, and the ICSID Additional Facility Rules. The difference lies, essentially, in the parties subject to each set of norms. While the Convention covers disputes where both parties are ICSID contracting States, the additional facility rules provides procedures for services rendered in conflicts where one party is not an ICSID contracting State, or where the dispute does not arise directly from an investment (and provided that the underlying operation is not an ordinary commercial transaction).72 Now, the debate on participation has been centered on arbitration, both within the Convention and the Additional Facility Rules. The origin of the debate lies on the exclusive and definitive nature of procedures under ICSID. Under Article 36(a), any Contracting State or any national of a Contracting State wishing to institute arbitration proceedings needs simply to address a request to that effect to the Secretary- General, who in turn sends a copy of the request to the other party. To be sure, under Article 25 of the Convention, consent on behalf of the defendant is required to initiate arbitration procedures: that is where IIAs enter into play. As we saw in the last section, one pillar of IIAs is their dispute settlement provision, which often refer to ICSID procedures and leave to the investor (who is often the complainant) the ability to establish, unilaterally, whether arbitration is applicable in their particular case. Consider Article 8(2) of the Swiss Model BIT:

- Si ces consultations n'apportent pas de solution dans un délai de six mois à compter de la demande de les engager, et si l'investisseur en cause y consent par écrit, le différend sera soumis au Centre International pour le Règlement des Différends relatifs aux Investissements (CIRDI), institué par la Convention de Washington du 18 mars 1965 pour le règlement des différends relatifs aux investissements entre Etats et ressortissants d'autres Etats. Chaque partie pourra entamer la procédure en adressant une requête à cet effet au Secrétaire général du Centre, comme le prévoient les articles 28 et 36 de la Convention. Au cas où les parties seraient en désaccord sur le point de savoir si la conciliation ou l'arbitrage est la procédure la plus appropriée, le choix revient à l'investisseur en cause. La Partie Contractante qui est partie au différend ne pourra, à aucun moment de la procédure de règlement ou de l'exécution d'une sentence, exciper du fait que l'investisseur a reçu, en vertu d'un contrat d'assurance, une indemnité couvrant tout ou partie du dommage subi.

It should be noted, moreover, that the Convention does not require the exhaustion of local remedies before acceding to international arbitration, and only exceptionally do IIAs provide for that requirement.73 As a result, investors have the ability of taking directly to ICSID most of their controversies. In turn, ICSID's decision is definitive. Under Article 53(1) of the Convention, the award is binding on the parties and cannot be subject to any appeal or to any other remedy except those provided by the Convention. As importantly, all parties to the Convention (that is, 150 States in the world) are required to enforce the award, even if they were not parties of the dispute (Article 54(1)). In practice, then, investors have the power to bypass domestic courts and seek a decision that, once taken, is recognized around the world, and is only contestable at ICSID. To be sure, fearing an uneven playing field, some States have effectively retired from ICSID's jurisdiction. Such is the case of Ecuador, which notified in November 2007 that it was unwilling to submit before ICSID any dispute arising from 'economic activities related to the exploitation of natural resources, like oil, gas, minerals and others.'74

C. Participation and the 'public interest' narrative in ICSID arbitration

Procedural norms of participation should be understood against this background. It is not merely the wish of being recognized as an active party to the conflict, but rather the need to open spaces that are not available at the domestic level, because investors are able to bypass the latter. Such spaces need to be understood, in turn, with reference to the three legal instruments that govern them: the Convention, the Additional Facility Rules, and the Rules of Procedure for Arbitration Procedures. The original Convention, for starters, is in force since 1966 and seems to consider participation of non-parties as irrelevant. More interesting for the purposes of this project, though, are the 2006 amendments of the Additional Facility Rules and the Rules of Procedure for Arbitration Procedures. As several privatization projects failed in the early years of this century, ICSID saw itself under the public spotlight, due to an unexpected wave of disputes involving developing countries. To be sure, the spotlight revealed controversial aspects of the procedures in the original Convention, and its rules of arbitration.

This feeling was much stronger in developing countries and within activist organizations, where the situation was perceived to have reached a critical phase.75 A case in point is the Aguas de Tunari dispute in Bolivia, which became the poster image of the failures of privatization and 'structural adjustment' policies of the 1990s.76 The dispute finds its origin in 1998, when the International Monetary Fund, IMF, started pushing privatization of public utilities as a condition for a US$138 million loan to Bolivia.77 In all truth, water supply in the city was quite a mess even prior to the privatization: the cost structure was such that the biggest consumers would pay the lowest price by cubic meter -in economic terms, they applied a decreasing marginal price. As a consequence, wealthy households, industry and agroindustry would pay low prices for each unit of the large amounts they consumed, while the poorest families would pay very high prices per unit of the little water they used.78 In 1999, privatization of water supply was indeed undertaken in Cochabamba, Bolivia's third largest city of more than 600.000 inhabitants. In September 1999, the city signed a lease with Aguas de Tunari, a consortium owned partly by Bechtel, a US infrastructure corporation. 79 The lease was followed closely by the enactment in the Bolivian Parliament of Law 2029 of October 29, 1999 (Ley de Servicios de Agua Potable y Alcantarillado Básico - Drinking Water and Sanitation Law) which, in essence, allowed the service operator to charge full cost to consumers.80

To be sure, Law 2029/99 was followed by steep hikes in water tariffs in Cochabamba, sparkling protests (some of them quite violent) in that city during the first months of year 2000, then spreading to other cities of Bolivia. In April 2000, then President (and prior Dictator, 1971-1978) Hugo Banzer declared the state of emergency,81 leading to the death of at least three people and several arrests, including that of Óscar Olivera, spokesperson of La Coordinadora (the grassroot organization leading the upraising movement).82 The state of emergency failed to calm protests and the Bolivian Government blinks first: on April 10, 2000, it signs an understanding with Óscar Olivera, in which it agrees to withdraw Aguas de Tunari, and to give control over water supply in Cochabamba to La Coordinadora.83 In February 2002, the investor filed a request for arbitration before ICSID, arguing that Bolivia had breached various provisions of the Netherlands- Bolivia BIT.84 Why the Netherlands BIT? Because 55% of Aguas de Tunari was owned by International Water, a company set up under Dutch law and owned, in turn, by Bechtel of the US (50%). The Tribunal was constituted in July 2002.

When informed about the arbitration procedures, La Coordinadora and other organizations filed a petition before the Tribunal in August 2002, where the organizations requested to be granted the status of parties in the dispute and, in the alternative, to be granted 'the right to participate in such proceedings as amici curiae, in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice, at all stages of the arbitration.'85 The Tribunal denied the petition. In a letter addressed to the petitioners, the President of the Tribunal argued stated:

- [Y]our core requests are beyond the power or the authority of the Tribunal to grant. The interplay of the two treaties involved [the ICSID Convention and the BIT] and the consensual nature of arbitration places the control of the issues you raise with the parties, not the Tribunal.86

The contrast between this decision and the approach taken in Methanex two years before is clear. While the Methanex tribunal seemed to understand that the issue at hand was not exhausted in reference to the parties in the dispute, the Aguas del Tunari ('Aguas') tribunal did the exact opposite. It stuck to its interpretation that the masters of the dispute were the parties -and since no party had given consent, the Tribunal could not go beyond. True, Methanex was decided under UNCITRAL rules, whose Rule 15 served as the basis for the Tribunal's central argument. Aguas, in contrast, was decided under the ICSID Convention. Yet, petitioners in Aguas presented an interpretation of Article 44 of the Convention that closely resembled that of Rule 15 in Methanex87 -in accepting the petition, the Aguas tribunal would have simply followed the momentum initiated by Methanex. But it did not do so. Instead, it decided to deny the petition, and acknowledged its jurisdiction over the dispute in October 2005.88 Ultimately, though, the dispute was settled: following heavy criticism by social and environmental NGOs, Bechtel finally settled the case in January 2006, agreeing with Bolivia that 'the concession was terminated only because of the civil unrest and the state of emergency and not because of any act done or not done by the international shareholders of Aguas del Tunari.'89 No compensation was paid to either side.

The 'Bolivian Water War', among other cases, placed enormous pressure over ICSID in terms of transparency and access. To be sure, the Aguas decision regarding amicus curiae did not help at all. The idea that these disputes involved nothing beyond the parties, as was held in Aguas, seemed to shock everyone that took some time to consider the matter. Here is a 2004 editorial piece of The New York Times discussing ICSID arbitration, entitled The Secret Trade Courts:

- [The] process itself is often one sided, favoring well-heeled corporations over poor countries, and must be made fairer than it is today. Unlike trials, arbitrations take place in secret. There is no room in the process to hear people who might be hurt [...] There is no appeal. [...] The trade agreements that set the rules should direct arbitration panels to take a much broader view -to consider not just corporate interests but the needs of governments and citizens. The panels should also be required to invite a wider range of views. Because their decisions have great public impact, arbitration panels owe the public a hearing.90

In the midst of such pressure, ICSID decided in 2006 to amend its Rules of Procedure for Arbitration, its Arbitration (Additional Facility) Rules, as well as its Administrative and Financial Regulations. The changes tried to tackle complains of lack transparency. For this purpose, the most notable amendment was the new Rule 37 of the Rules of Procedure for Arbitration, which concerns the submission of amicus briefs. New Rule 37 created a formal space for such submission before ICSID tribunals, and allowed for parties to the dispute to be consulted -however, and this is the part that is particularly notable, parties lack the right to veto the admission of the amicus brief.

How has Rule 37 worked in connection to global political participation? The first and, to the time of writing, only case to have been tried in its entirety under the new rule is Biwater.91 An interesting dispute that provides a glimpse of Rule 37's inner workings, the Biwater case concerned the privatization of water supply in Dar es Salaam, capital of Tanzania, undertaken under conditions imposed by a funding agreement of US$140 million between Tanzania and the World Bank, the African Development Bank, and the European Investment Bank.92 A British company (Biwater Gauff Tanzania Ltd., here in after 'BGT') bid and won the contract (a lease, in strict sense); however, after two years of service (from 2003 to 2005), and after attempts at renegotiation and strict review of performance, the Tanzanian government decided to terminate the lease, as it felt that City Water (the vehicle corporation created by BGT to execute the contract) was not providing an appropriate service to millions of its consumers.93 Tanzania then took over the headquarters of City Water in Dar es Salaam, and proceeded to detain and deport BGT's senior management.94 A one page ad was published in The Guardian of Tanzania, where it was made clear that Dar es Salaam Water and Sewerage Corporation, DAWASCO (the domestic operator, wholly owned by the Tanzanian Government) would take over the service.95

Under the Tanzania-UK BIT, BGT asked for arbitration under ICSID rules. To be sure, the dispute caught the attention of several activist organizations and some academic observers. First of all, BGT claimed that Tanzania's effort of regulating its domestic water supply had expropriatory effects, and violated standards of fair and equitable treatment.96 As the scenario played out, the stark opposition between regulatory sovereignty, the environment and development, in one hand, and foreign investment law, in the other, became evident: here is an example, the most moderate would say, of an investment decision that may entail a perverse effect of regulatory chill. Host States would now have second thoughts when taking regulatory measures regarding water, affecting thus their ability to protect their environment, the health of their population, and their sustainable development.97

Moreover, and perhaps more importantly, Biwater appeared to be an exceptional example of an often commented, but rarely confirmed, practice in privatization in developing countries: underbidding, also called a 'renegotiation strategy.'98 In essence, the practice has a foreign investor bidding for a project at rates well below its costs, in order to win the contract. Once the deal is secured and advance payments have been done, the investor complains that rates included in the original contract are too low, due, for example, to exchange rate variations or a changing tax environment. A renegotiation of the contract is then requested. The host State, in turn, has the option of either resisting the renegotiation and seek adjudication on the dispute (thus incurring in high legal costs and the risk of suspension of a crucial service for its population), or revising the contract and pay rates that are higher than the original contract, but lower than the costs of litigation. Even though global estimates seem to be unavailable, according to some commentators 75% of all infrastructure projects in Latin America are renegotiated, 66% of which are initiated by the investor.99 The Biwater dispute is notable in this regard as, during its two years of operation, BGT requested a renegotiation of its contract - only to be turned down by Tanzania. Notably, though, Tanzania succeeded in introducing as evidence an independent audit by global auditing firm PriceWaterHouseCoopers, performed during the concession, which stated that City Water had not demonstrated any of the grounds that would justify a tariff adjustment under the lease.100 With this piece of evidence on file, activist organizations saw the Biwater case as an excellent opportunity to put forward the problem of regulatory chill and, more importantly, the complex issue of underbidding.

To that effect, then, several organizations directed their energies at submitting briefs before the ICSID tribunal. Even though the dispute had began before the amendment of the Rules of Procedure for Arbitration had entered into force (including new Rule 37), both parties agreed that the new rules would be applicable.101 On November 27, 2006, five NGOs submited a 'Joint Petition for Amicus Curiae Status,'102 where they requested '(a) Status as amicus curiae in the present arbitration; (b) Access to the key arbitration documents; and (c) Permission to attend the oral hearings when they take place, and to reply to any specific questions of the Tribunal on the written submissions'.103 To justify the relevance of their intervention, the brief put forward a textual test on the basis of new Rule 37. In sense, the brief divided the text of the rule in four blocks, and presented the reasons why their brief fulfilled with the requirements of each block.104

Two aspects are of interest in that argumentation: first, the brief underscores the fact that, in order to decide whether the brief is acceptable, the tribunal has the competence to consider, 'among other things', the reasons included in Rule 37. This means, according to the brief, that the Tribunal is able to consider different motivations (different, that is, from those of Rule 37). There is, for the petitioners, a wider interest here, beyond the interest of the parties. Following that logic, the brief tries to make the point that a fundamental reason why the brief should be considered is the 'public credibility of the process', achieved, inter alia, through the acceptance of amicus curiae briefs.105 In this way, the organizations link the problem of legitimacy with that of participation through amicus briefs, in a move that will prove to be useful to reveal the mindset in which the tribunal understands the relevance of participation. The second interesting aspect of the brief is its contention that lack of access to the parties' submissions and evidence hinders the possibility of achieving the objective of Rule 37.106 As a consequence, then, the brief links the submission of amicus curiae to a wider argument regarding confidentiality and secrecy during the arbitration process: if Rule 37 is to be taken seriously, the brief seems to suggest, then access to documentation must be provided.

Following language in Rule 37, the tribunal asked BGT and Tanzania for their opinion on the submissions. BGT objected all three submissions put forward in the briefs, arguing that general policy opinions regarding privatization and free trade were neither necessary nor directly connected to the issues of law discussed in the dispute; thus, amici status should be denied.107 Moreover, BGT suggested the brief submission required access to a wide range of documents, some of them extremely confidential. BGT considered such access inappropriate.108 Finally, the applicants considered that, unlike brief submissions, access to hearings does require consent of both parties under new Rule 37. They denied such consent.109 Tanzania, in contrast, considered that the briefs should be accepted: they could contribute to the discussion and did not risk being disruptive.110 On the point regarding attendance to hearings, though, the defendants agreed with BGT: under new Rule 37, consent was required and if the complainant would not agree to such attendance, it could not happen.111

When deciding the issue, the Tribunal was emphatic in holding that, unlike the expression 'amicus curiae status' could lead to believe, new Rule 37 does not create a new system of legal standing during the overall arbitration. Quite on the contrary, Rule 37 merely opened two limited spaces for non-party involvement: amicus briefs, and attendance to hearings. This is important, in the Tribunals words, 'lest it be misunderstood that once any type of permission to participate is given to a non-disputing party, the latter may then be entitled as a right to all other procedural rights and privileges.'112 Yet, despite this restrictive rhetoric, the tribunal did consider the wider narrative of public interest put forward by the brief, holding that:

- [A]llowing for the making of such submission by these entities in these proceedings is an important element in the overall discharge of the Arbitral Tribunal's mandate, and in securing wider confidence in the arbitral process itself.'113

Thus, and quoting extensively language from Methanex, the Tribunal seemed to acknowledge that this dispute involved issues that went beyond the mere disagreement with regards to a lease contract. There was, indeed, a public interest in this arbitration.114 The tension between such interest and restrictive procedural rules was, then, solved through a balancing act: considering the late phase in the proceeding in which this debate was taking place, briefs would be admitted, yet through a two-step process that allowed parties to react to the first submissions, and object subsequent briefs.115 As to attendance to hearings and access to documentation, the Tribunal held a more restrictive, yet still meaningful, view. The Tribunal denied access to documents, yet not on the basis of confidentiality, as one may expect it would have, but rather on arguing that granting such access at that stage would endanger the 'procedural integrity' of the proceedings.116 Building on such concept, the Tribunal denied access 'for the time being only', allowing thus for the possibility that wider access to documents would be given at a later stage.117 Finally, access to hearings was denied, following the same interpretation of new Rule 37 put forward by BGT.118

A couple of months after this ruling, the organizations filed their amicus brief. Predictably enough, given the limitations imposed on access to documentation, the brief was able to address neither factual points nor specific legal arguments as put forward by the parties. This fact makes the brief an exercise on speculation regarding the possible points that may have risen in the exchange between the parties, and amici are quick to acknowledge as much.119 Despite its limitations, the brief does bring home the point perceived by the applicants to be of central importance: this is not a matter of environment or human rights against investment protection, but rather a matter solely of investment protection. And, in the context of investment protection, 'Bilateral Investment Treaties are not insurance policies against bad business judgments.'120 According to the brief, the investment regime is not merely a collection of rights on behalf of the investor, but also entails certain responsibilities.121 One of such responsibilities is a basic level of diligence when planning an investment122 -a duty of diligence that is made more important (and thus, more demanding) when failure of the investment risks entailing wide spread suffering, illness and death.123 The brief then goes to assess the problem of underbidding: it argues that, though evidence of a specific act proving underbidding is unavailable, BGT's actions taken as whole do seem to point towards a renegotiation strategy being deployed.124 As conclusion, amici submit that, considering the investor's lack of diligence and unsuccessful performance, Tanzania should not be found responsible of unlawfully terminating the lease.125 Quite on the contrary, given the alleged renegotiation strategy deployed by BGT, amici believe the Tribunal should take a stand against investors trying to capture the legal regime to achieve compensation when such strategy fails.126 Following this submission, during the second of the two-step approach adopted by the Tribunal, both parties to the dispute agreed that a second submission was not needed. No further amicus curiae briefs were thus submitted.127

The Tribunal's final award on Biwater came as a bittersweet victory to those who submitted the briefs. In a controversial decision, the Tribunal held that Tanzania had indeed violated the standards of fair and equitable treatment, expropriation, and full protection and security, as included in the BIT.128 However, the Tribunal found that no compensation was in order, as BGT's claim failed to proved a causal link between the Tanzania's actions and the alleged injury. For the Tribunal, its conclusion are 'based on the lack of linkage between each of the wrongful acts of the Republic, and each of the actual, specific heads of loss and damage for which BGT has articulated a claim for compensation. In other words, the actual loss and damage for which BGT has claimed -however it is quantified- is attributable to other factors.'129

This is a remarkable conclusion that is bound to have important consequences. First of all, it undertakes a frontal analysis of causation that was decidedly evaded during years of discussions concerning the law of State responsibility -in particular, with regards to the linkage between causation, compensation and expropriation.130 Moreover, the award seems to open a new of understanding the 'sole effects doctrine,'131 where lack of evidence in causation would entail that expropriatory acts may not necessarily lead to compensation. This could mean, in effect, a way of interpreting the doctrine in a very restrictive way. For the purposes of the argument made here, suffice it to say that the Tribunals approach is indeed politically and legally groundbreaking. How did the briefs influence such decision? The answer has two parts. On the substantive part of the decision, Amici were not decisive. The award does include a section entitled 'The Amici Brief' that quotes extensively from arguments put forward by the organizations; in a style that denotes respect and appreciative consideration.132 And yet, as to relevance, all the award had to say is the following:

- As noted earlier, the Arbitral Tribunal has found the Amici's observations useful. Their submissions have informed the analysis of claims set out below, and where relevant, specific points arising from the Amici's submissions are returned to in that context.133

To be sure, this promise is not wholly kept. Besides the section mentioned earlier, only two further references (of any kind) are made to Amici in the award. The first one is a footnote concerned with a testimony, and states: 'It may be noted that this evidence was apparently not available to the Amici at the time they submitted their Brief, and hence they contended that the dearth of chemical stocks justified the Government's intervention.'134

The second reference, though, goes directly to the heart of the brief's main contention: investor's obligations under the regime. In this point, the Tribunal referred in passing that it 'had also taken into account the submissions of the Petitioners.'135 To which extent did the Tribunal actually do that? This is the second part of the answer -which is, once again, bittersweet. The Tribunal did follow the mindset presented in the brief -that is, it accepted that more than just the interest of the parties were involved, and held that part of the dispute was concerned with investor duties, and the fact that foreign investment law cannot work as an insurance against common risk or poor business planning.136 However, when applying such framework, the Tribunal decided in every single count against Tanzania: the Republic had indirectly expropriated BGT, had failed to provide full stability and security and had failed to provide fair and equitable treatment to the investor. The tighter standard of diligence on behalf of the investor, as put forward by the brief, was not considered. It was only due to the causation issue (which was not mentioned in the brief) that BGT failed to walk with a multimillion award in its bank account. Moreover, the Tribunal did not engage in an open exercise of pondering and balancing competing principles -for example, protection of foreign investment and protection of the environment, or human rights. Instead, in line with the strategy adopted by the amicus brief, the Tribunal analyzed the issue from an exclusively investment point of view, and decided based on that rationale on Tanzania's actions.

The Biwater saga draws the picture of a Tribunal that understood that there was indeed an important value underlying this dispute -a matter of 'public interest', if one wills. In line with Methanex, that underlying value is never stated, and the Tribunal seems reluctant to make it an express part of its reasoning of the award, and its conclusions. However, the public interest involved does call for open participation through, for example, amicus briefs -which, for the Tribunal, 'provide a very useful initial context for the Arbitral Tribunal's enquiry' and 'provid[e] a useful contribution to the proceedings'. While the environment and human rights were the actual issues at stake, the Tribunal directed its attention to the problem of legitimacy, and framed issue as a matter of participation, a point that is expressly put forward by Amici. This participation seems to relieve some pressure from the Tribunal as decision maker lacking legitimacy, but fails in pressing the Tribunal to frame its reasoning as a matter of conflict of values. Instead, the Tribunal decides solely on the language of investment law -informed by Amici. Participation, in this context, seems to have been a proxy for the substantive debate that lied behind this dispute. Though celebrated as having given 'institutional legitimacy' to amicus curiae in ICSID litigation, Biwater fails to bring non investment concerns to such forum -or at least to do so explicitly. In that context, while the award is, without a doubt, a victory for the organizations that were involved, it seems to be a defeat to Tanzania, and (at the very least) neutral in terms of human rights and environment in investment law.

CONCLUSION

This paper tried to present in detail the stakes and issues involved in the debate of participation before arbitral tribunals of foreign investment law. Exception being made of the Aguas decision, it showed that the "public interest narrative" is quite common. In general terms, it seems to be often understood that that there are interests in this sort of disputes, not represented by the parties, that are nonetheless relevant for the process of adjudication. As stated in the introduction, the argument in this paper is not normative. It is not my intention to argue that participation should become a central aspect in the procedure of investment litigation. Rather, I showed how participation is a crucial part of the investment arbitration mindset, not in a subsidiary role or as a mere legitimating devise, but as an expression of a substantial world view -referred here as the "public interest narrative" in foreign investment arbitration. Scholars and practitioners working in foreign investment law would be, thus, well advised in going beyond the view that participation in arbitral procedures is a contentious issue pushed by some activists in Geneva or Washington D.C.