Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

International Law

versión impresa ISSN 1692-8156

Int. Law: Rev. Colomb. Derecho Int. no.24 Bogotá ene./jun. 2014

THE UNITED STATES FOREIGN CORRUPT PRACTICES ACT AND LATIN AMERICA: THE INFLUENCE OF LOCAL PROSECUTORIAL EFFORTS IN TRANSNATIONAL WHITE-COLLAR LITIGATION

LA LEY DE PRÁCTICAS CORRUPTAS EXTRANJERAS DE ESTADOS UNIDOS Y AMÉRICA LATINA: LA INFLUENCIA DE LOS ESFUERZOS PROCESALES LOCALES EN LOS LITIGIOS TRANSNACIONALES DE CUELLO BLANCO

Daniel Pulecio Boek*

*Primary law degree from the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana in Bogotá D.C., Colombia. Graduated with various honors. Law degree from the University of the Basque Country in Saint Sebastian - Spain. Master Degree in Philosophy in the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana (Thesis pending). Master in Laws from Harvard University, United States of America. LL.M. paper received Honors. Currently accepted to the MSc in Criminology and Criminal Justice in Oxford University, UK. Formerly practiced in Colombia for nearly 4 years as a litigator and consultant with the firm Sampedro & Riveros Abogados. Currently an international lawyer at the firm Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton, Washington D.C. (Admission to the New York Bar pending.) Author of the books Crimes Against the Social and Economic Order, and The Dynamic Burden of Proof in Criminal Matters. Author of several articles and essays published nationally and internationally. Former professor at the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Email: dpulecio@gmail.com. My opinions do not represent the ideas of any institution with which I am currently involved. In consequence, all the thoughts expressed in this paper are my sole responsibility and uniquely the product of my intellect.

Para citar este artículo / To cite this article

Pulecio, D., The United States Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and Latin America: The Influence of Local Prosecutorial Efforts in Transnational White-Collar Litigation, 24 International Law, Revista Colombiana de Derecho Internacional, 21-58 (2014). doi:10.11144/Javeriana.IL14-24.fcpa

Abstract

Within the field and practice of White-Collar criminality and litigation in the transnational sphere, the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act occupies a central role. When a corporation bribes a foreign public official, the FCPA as well as local Penal Codes will be violated. Therefore, an individual and/or corporation could eventually be prosecuted by local authorities and the US Department of Justice under the FCPA. This presents double jeopardy and collateral estoppel issues, which this paper will address. Furthermore, this paper will focus in Latin American comparative criminal law, to analyze the influence that could -or should- be exerted over the DOJ with transnational white-collar litigation strategies. Primarily this paper suggests that active involvement of corporations in local prosecutorial efforts in Latin America can bring beneficial consequences in DOJ conducted FCPA investigations.

Keywords author: Foreign corrupt practices act, white-collar crime, comparative criminal law and procedure, Latin America, transnational litigation strategies, double jeopardy, dual sovereignty doctrine, collateral estoppel.

Keywords plus: Corrupt practices, white collar crimes, criminal law, trials, litigation, res judicata, sovereignty, estoppel.

Resumen

Dentro del campo y la práctica de la delincuencia de cuello blanco y los litigios en el ámbito transnacional, la Ley de Prácticas Corruptas Extranjeras (FCPA, por sus siglas en inglés) ocupa un papel central. Cuando una empresa soborna a un funcionario público extranjero, la FCPA, así como los códigos penales locales son violados. Por tanto, un individuo y la corporación eventualmente podrían ser enjuiciados por las autoridades locales y el Departamento de Justicia bajo la FCPA. Esto presenta un doble enjuiciamiento e impedimentos colaterales que se abordarán en este artículo. Por otra parte, este artículo se centrará en el derecho penal comparado latinoamericano, para analizar la influencia que podría-o debería- ser ejercida sobre el Departamento de Justicia con las estrategias transnacionales de litigio de cuello blanco. Principalmente, este artículo sugiere que la participación activa de las empresas en los esfuerzos fiscales locales en América Latina puede traer consecuencias beneficiosas en el Departamento de Justicia que haya realizado investigaciones FCPA.

Palabras clave autor: Ley de prácticas corruptas extranjeras, crimen de cuello blanco, derecho penal comparado y de procedimiento, América Latina, estrategias de litigio transnacionales, doble enjuiciamiento, la doctrina soberanía dual, impedimento colateral.

Palabras clave descriptores: Prácticas corruptas, delitos de cuello blanco, derecho penal, procesos, litigios, cosa juzgada, soberanía, impedimento y reacusación.

Summary

Introduction.- i. the foreign corrupt practices act.-ii. the issues concerning double jeopardy and the FCPA.- A. The Influence of Local Enforcement Efforts and their Results over FCPA Prosecutions. - B. The Role of Corporations in Criminal Investigations.- C. The Influence of Foreign Prosecutions in Light of the United States Attorney's Manual and other Relevant Documents.- III. double jeopardy .- A. Generalities and the "Same Offense" Requirement.- B. The Dual Sovereignty Issue.- C. Collateral Estoppel.- iv. practical application and conclusion.- Bibliography.

Introduction

Several types of criminal offenses can be included within the realm of white-collar criminal law. Within the category of white-collar criminality, the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) occupies a prominent place. Its central role in white-collar litigation is a result not only of the very active enforcement efforts of the Department of Justice (DOJ) but also of its importance in international trade. It is undeniable that few other areas in white-collar crime have received so much judicial and academic attention during the past decades.

The FCPA is one of the most active areas of prosecution in which the DOJ has engaged during recent years. Consequently, it is a subject matter that has been abundantly developed in case law and widely discussed by scholars. However, among the debated topics, it is not common to find references concerning the influence, if any, on the prosecution carried out by the DOJ, of the results of criminal enforcement efforts undertaken by the local authorities of the country in which a Corrupt Practice occurs. Hence, this paper will analyze the following issues: 1) what is the influence of local enforcement efforts and its results, in an investigation conducted by the DOJ; 2) whether double jeopardy attaches to corporations prosecuted under the FCPA after the termination of a criminal proceeding carried out by local authorities, and 3) how the conclusions of the above mentioned issues can be strategically applied to FCPA litigation.

Because of the distinct legal cultures and traditions in each region of the world, I will focus in Latin America, but some references will be made to Europe and Africa. However, before the analysis of each of the abovementioned issues, I will present some introductory remarks about the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

I. The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act

Around the late 1970s, US companies were engaging in widespread bribery of foreign public officials. The US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act was enacted in 1977 with the purpose of putting a stop to such conducts and with the objective of promoting an honest and reliable marketplace for businesses1. The FCPA contains anti-bribery provisions as well as accounting provisions. This paper will not develop or analyze the specific provisions of the FCPA. Numerous other works have undertaken such task. This essay will focus exclusively, on the much less explored issue of the relations between foreign enforcement efforts and DOJ investigations of FCPA violations. However, the bribery and accounting provisions may be abbreviated as follows:

"The anti-bribery provisions prohibit us persons and businesses (domestic concerns), US and foreign public companies listed on stock exchanges in the United States or which are required to file periodic reports with the Securities and Exchange Commission (issuers), and certain foreign persons and businesses acting while in the territory of the United States (territorial jurisdiction) from making corrupt payments to foreign officials to obtain or retain business. The accounting provisions require issuers to make and keep accurate books and records and to devise and maintain an adequate system of internal accounting controls. The accounting provisions also prohibit individuals and businesses from knowingly falsifying books and records or knowingly circumventing or failing to implement a system of internal controls"2.

The FCPA was enacted in 1977 as a result of a series of discoveries made by the Securities and Exchange Commission. The sec discovered that nearly 400 US companies had paid millions in bribes to foreign officials for the purpose of obtaining business abroad. Furthermore, sec investigations revealed companies were falsifying their records to conceal the payments3. Thus, the enactment of the FCPA was intended to halt corporate bribery, thereby cleansing the image of us companies and promoting an adequate operation of the markets.

The FCPA has experienced two major reforms. First, in 1988 Congress amended the FCPA to include two affirmative defenses. Later, Congress requested the President to negotiate a treaty within the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Said negotiations culminated in the Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Officials in International Business Transactions, coming into force in February 1999, with the United States as a founding party. Some of the US major trading partners were parties to the treaty, which among other things, required them to criminalize the bribery of foreign public officials4. Several countries in Latin America have undertaken efforts to become part of the Convention. In 1998, the FCPA was for the second time amended, to conform to the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention.

In the United States, corporations can be criminally liable5. This means that not only individuals (natural persons) can commit criminal offenses. The general rules and principles of corporate criminal liability apply to the FCPA. Hence, a corporation can be subject to prosecution, trial and ultimately be convicted, if its directors, officers, employees or agents, acting within the scope of their employment engage in a corrupt practice, provided the intention of such action was, at least in part, to benefit the company. Additionally, corporations can also be found criminally responsible under the application of parent-subsidiary principles of liability and successor liability in cases of M&A6. Furthermore, not only corporations are covered by the FCPA, legal entities than can be criminally prosecuted for actions of its agents include partnerships, associations, joint-stock companies, business trusts, unincorporated organizations, and sole proprietorships7.

Procedurally, it is worth mentioning that once the DOJ launches an investigation for an FCPA violation it can indict the entity or natural persons, subscribe plea agreements, deferred prosecutions agreements, non-prosecution agreements, or fully decline prosecutions8. This paper will focus on litigation strategies aimed at persuading the DOJ to decline prosecution.

However, if an indictment is issued and ultimately the jury convicts, consequences include imprisonment, fines, civil penalties, debarment, cross-debarment by Multilateral Development Banks and loss of export privileges9.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that us laws include whistle-blower provisions. Whistleblower rules, regulate the rights of internal informants and provide certain levels of protection to them.

Since its enactment, the FCPA has been actively enforced by the doj. It has been considered one of the most important instruments to combat transnational corruption and to secure a fair environment for international business transactions. Especially within the last decade, FCPA prosecutions have become a primary area of concern for the Department of Justice. Investigations have grown in number and the consequences seem to have increased in gravity and endurance. FCPA investigations have resulted in payment by corporations of multimillion dollar settlements and/or fines and in the design and implementation of rigorous compliance programs, directed at preventing future FCPA violations10. Furthermore, FCPA prosecutions have become especially publicized in the public opinion, receiving broad media coverage.

The United States' fight against transnational bribery is so persistent and significant that the oecd has commended us enforcement efforts11. Thus, it is impossible to deny the importance of the fcpa within the United States and its significance in the battle against international corruption.

Finally, one must take into account that the doj is not the only entity responsible for FCPA enforcement. The sec is in charge of civil enforcement, and therefore, civil penalties fall within the domain of the sec. Other agencies, even though they do not bare enforcement powers, in furtherance of their duties they deal with issues related to possible corrupt practices. Said agencies include the Department of Homeland Security, the Internal Revenue Service and the Departments of State and Commerce.

II. The issues concerning double jeopardy and the FCPA

A. The Influence of Local Enforcement Efforts and their Results over FCPA Prosecutions

Criminal prosecution for bribery of public officials is mandatory in all jurisdictions in the Latin American region. As I will explain below, within local enforcement efforts in Latin America, corporations can play two types of roles when they are involved —through their employees— in bribery situations. The bribery articles in Penal Codes across Latin America are very similar -with respect to the nature of the conduct punished as well as with regards to the consequences of the criminal offense to the bribery provisions under the FCPA. Therefore, this chapter will address two issues. First, I will analyze the different roles a corporation can play in criminal prosecutions for bribery of public officials in Latin American jurisdictions, and second, I will evaluate the influence —if any— that foreign prosecutions currently exert upon investigations carried out by the us Department of Justice under the FCPA. For this purpose, I will give special consideration to the United States Attorneys' Manual and the factors it includes to guide Federal Prosecutors in the investigation of corporations when other jurisdictions have prosecuted the same conduct.

B. The Role of Corporations in Criminal Investigations

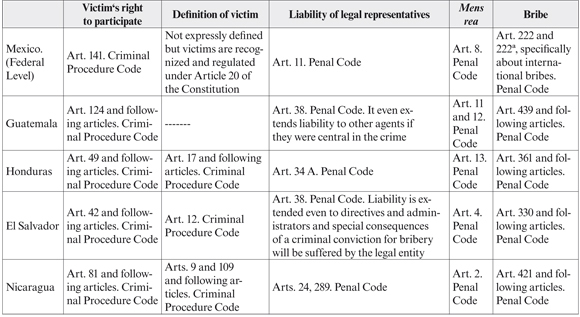

In the majority of Jurisdictions in Latin America (Latin America is generic term used in this paper intended to designate Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean and South America) victims of crimes have the right to participate in the criminal proceedings undertaken against the agent12. A "victim" has been generally understood as an individual or legal entity (such as a corporation) which suffers the consequences (at least economical) of a criminal conduct13. In that sense, the Declaration of Basic Principles of Justice for Victims of Crime and Abuse of Power, pronounced by the General Assembly of the United Nations defines victims as "persons who, individually or collectively, have suffered harm, including physical or mental injury, emotional suffering, economic loss or substantial impairment of their fundamental rights, through acts or omissions that are in violation of criminal laws operative within Member States, including those laws proscribing criminal abuse of power"14.

Keeping in mind that all nations in Latin America consider bribing public officials a criminal offense, the first question one may ask when an employee of a corporation in Latin America engages in conduct prohibited by the FCPA is whether the corporation —as a sufferer of the negative consequences of said conduct— could choose to participate as a victim before local authorities in the prosecutions and/or subsequent trials held against the employee(s)/former employee(s) and/or the public official who received the bribe. It is clear that a corporation under such a fact pattern could chose to procedurally participate as a victim, because it falls within the definition of a "victim". A corporation experiences adverse consequences (including damaging, legal, economic and reputational effects) when one of its employees behaves in a manner banned by the FCPA.

Nonetheless, it seems evident that a corporation could not be considered a victim when the corporation "itself" executes the forbidden course of conduct. Penal Codes in Latin America do not usually allow corporations to be considered criminally liable, but they all however, make it possible for a corporation itself to be held as the agent of a criminal offense. Some crimes describe courses of conduct that could be perpetrated by a legal entity. When this is the case, and thus, when it is possible to assert that a corporation itself engaged in criminal conduct, the employee that local authorities will prosecute is the legal representative15. In other words, liability will fall on the representative, despite the fact that the "agent" of the crime was the entity on behalf of which he or she was acting.

However, one must take into account that usually, when a corporation is being treated as the agent of a crime, such a situation will be the result of a conduct carried out, precisely, by its legal representative. This means that —generally— if a corporation is deemed as the active perpetrator of an offense, it will be because an individual with capacity to bind the entity (the legal representative), acting within the scope of its relationship with the corporation and in furtherance of that relationship, engaged in a criminally forbidden course of conduct.

In conclusion, when a conduct prohibited by the FCPA takes place in Latin America, corporations only have two options: either they are considered victims, or they are considered "agents" of the crime, and their legal representative will be prosecuted.

The question this paper will address is whether an active and cooperative behavior by a corporation with local authorities, as a victim or even as the prosecuted entity, bares any influence over doj conducted FCPA prosecutions.

It seems likely, that the nature of such cooperative behavior will dramatically vary in cases in which the corporation is a victim as compared to situations where the corporation itself is investigated. In any event, the result will be the same: local authorities will produce a definite judicial resolution or verdict of guilt or innocence. Thus, it seems reasonable to infer that when an entity is a victim, it will seek to move forward the case —and therefore, actively cooperate with the prosecution— against the employee/former employee, in order to secure a criminal conviction and/or obtain the payment of damages caused. If the corporation itself is being subject to investigation as a result of the actions of its representative, then it will seek to move the case forward in order to obtain an acquittal. Alternatively, it can try to cooperate and make an agreement with local authorities. Nevertheless, it is important to note that in a number of jurisdictions in Latin America, prosecutorial discretion and in general, the possibility of executing agreements with enforcement authorities to avoid criminal prosecution, is not as broad as in the United States.

C. The Influence of Foreign Prosecutions in Light of the United States Attorney's Manual and other Relevant Documents

The United States Attorney's Manual (usam) contains the guidelines for the exercise of duties entrusted to Federal Prosecutors. Section 9 provides guidelines for criminal investigations and Chapters 27 through 28 of this Section deal with the Principles for Prosecution in general, and for prosecution of Business Organizations in particular. The factors included in the Manual, to be taken into consideration by us Attorneys when making prosecutorial decisions, are not mandatory. The Manual includes non-compulsory criteria to be evaluated during the performance of prosecutorial functions. Nonetheless, even though they are not forcefully binding on Federal Prosecutors, the provisions set forth in the Manual do provide an important element of analysis for understanding the influence —if any— exerted upon the Department of Justice by enforcement efforts undertaken abroad. I will focus, in particular, on the weight that could — at least theoretically — be given by the doj when conducting FCPA investigations, to the cooperation of corporations with local authorities, and furthermore, to the results of local criminal proceedings.

The United States Attorneys' Manual (usam) in § 9-27.22016 (within the section containing the Principles of Federal Prosecution) establishes as a ground for declining prosecution, the fact that the "person is subject to effective prosecution in another jurisdiction". Consequently, the doj when conducting a criminal investigation against a corporation for a corrupt practice in Latin America will balance certain factors to determine whether prosecution shall be declined. Among the factors to be weighed the usam includes the interest of the other jurisdiction in that prosecution, the ability and willingness of that jurisdiction to prosecute effectively, and the probable consequences of conviction (usam § 9.27-240)17.

If a corporation acted as a victim or as an "adversary" before local authorities, for this purpose, is irrelevant. The prosecutorial efforts undertaken by Latin American authorities should —in any event— have an important influence in the doj discretional decision to charge the corporation under the FCPA. This is especially true in the Latin American context, when one takes into account two circumstances: 1) No country in the region can be deemed a "failed state" that cannot effectively prosecute crimes for lack of necessary judicial resources and 2) Bribery practices, with no exception in the region, are considered criminal offenses and thus, carry significant prison terms and high fines such as those prison terms and fines that could be imposed under the fcpa18.

Notwithstanding, according to the comments of usam § 9.27240, the Principles of Federal Prosecution thus far cited, seem to be directed to jurisdictional conflicts between Federal and State or Local authorities, rather than to issues with foreign (non-us) jurisdictions. However, nothing is expressly stated in the Manual or its comments, so as to preclude its application to transnational multiple prosecutions.

Under the guidelines for Federal Prosecution of Business Organizations (usam § 9-28 300)19, the same general Principles of Federal Prosecution should be followed and several other factors must be considered when deciding whether to decline prosecution. Some of those other factors are directly related to a successful prosecution by local authorities abroad, as a result of the active participation and cooperation of a corporation20.

I am referring in particular to the cooperation in the investigations of its agents, the disclosure of wrong doing, the remedial actions taken in general and in particular against the responsible employees, and the adequacy of the prosecution against those individuals. Hence, the active and diligent participation of a corporation in the criminal enforcement efforts undertaken by local authorities in a case of bribery of public officials, under the usam will represent important capital before the doj. When the doj is conducting an FCPA investigation, it will evaluate if the corporation has cooperated in the investigation of its agents, if it has promptly disclosed the wrongdoing, and if the prosecutorial results against the responsible individuals are adequate.

Thus, if a corporation has assertively cooperated in a bribery investigation with local authorities and if the results of the enforcement efforts have been successful, then, at least under the Manual, us Federal Prosecutors should ponder in favor of the corporation such circumstances, when addressing whether to decline prosecution.

The American Bar Association (aba) Standards, even though not binding on prosecutors, also establish an important element of analysis for understanding the influence of foreign criminal proceedings over doj investigations. The aba stresses that prosecutors should take into account the "availability and likelihood of prosecution by another jurisdiction" when deciding to charge21. Therefore, if a corporation has been successful —through its active involvement— in securing a conviction against the responsible individuals, for a foreign bribery violation, also punishable within the us under the FCPA, the doj acting pursuant to the aba standards, could decline prosecution.

The recently issued FCPA Resource Guide also sheds an important light on this issue. It reiterates all these notions as relevant factors for the doj to ponder when determining to charge, negotiate pleas or agreements or decline prosecution. However, it does not mention prosecution by foreign jurisdictions as a cause for recent cases of declination22. Nonetheless, some have considered that the doj in the Statoil case in 2006 gave serious weight to the results of the proceedings in Norway when deciding to resolve the case with a deferred prosecution agreement23. Therefore, the Statoil case may well be considered the only recent precedent of doj declination of prosecution for an FCPA violation, as a result of a successful foreign criminal investigation.

In conclusion, prosecution by foreign jurisdictions of bribery offenses (and thus, cooperation of corporations in those local efforts), under the usam, the aba Standards and the fcpa Resource Guide, is one of the factors to be taken into account by Federal Prosecutors when they exercise the discretionary judgment of whether to charge or celebrate certain types of agreements for fcpa violations. At least theoretically, this assertion is uncontested, although in practice, only one recent case can be brought to our attention, where the doj declined prosecution based on foreign enforcement efforts.

III. Double jeopardy

The right not to be placed twice in jeopardy for the same offensethe protection against Double Jeopardy -is awarded recognition under the Fifth Amendment of the United States Constitution. It is important to bear in mind, for the purpose of this paper, that Double Jeopardy applies to corporations as well as individuals.

Below, I will explain some distinctive aspects of the guarantee against Double Jeopardy. In essence, it precludes multiple prosecutions against one individual for the same offense. I will not address the variations Double Jeopardy has historically endured in Supreme Court decisions24. I will focus exclusively on its current comprehension. Furthermore, we should keep in mind that it has been incorporated to the Fourteenth Amendment and therefore, made applicable to the states25.

Part 2.1 of this paper will analyze exclusively an issue applicable to corporations as defendants in the United States when they are deemed to have been the "agents" of a crime under a local Latin American jurisdiction. If a corporation "itself" committed a crime of bribery abroad, then its legal representative would be subject to prosecution, as I have addressed above.

Thus, this paper will assess the significance of such local prosecutorial efforts in doj investigations under the FCPA. I will argue that the doj must —as a matter of law— decline prosecution against a corporation under the FCPA if it has been convicted or acquitted —through its legal representative— in a foreign Latin American jurisdiction. According to what this paper has analyzed thus far, foreign prosecutions only receive consideration as one of many other factors to be evaluated, when the doj determines whether to decline prosecution. A determination, that is discretional in nature. This paper will move foreign prosecutions from being just another element to be considered to a binding matter of law.

We will also analyze the dual sovereignty doctrine. Under dual sovereignty, a person shall not be placed twice in jeopardy for the same offense if two or more sovereign jurisdictions are involved. When more than one sovereign can prosecute an offense based on its own independent power and authority, double jeopardy does not apply. However, I will argue that with respect to bribery of foreign officials —and in general— with respect to transnational corruption, nations share sovereign power. I claim that the United States and Latin American nations are part of the same international effort to defeat public corruption, as a consequence of which they have executed three vital legally binding instruments. In virtue of those instruments they have sacrificed their power to criminalize bribery. Thus, the authority of states in the American region to punish and prosecute corruption is not independent. On the contrary, it is shared because it derives from common international mandatory obligations.

Finally I will address the collateral estoppel doctrine. Thus far we will have analyzed issues concerning the prosecution of corporations in the us after a legal representative of the entity abroad has been prosecuted as a result as a treatment of the corporation itself as the agent of the offense. Collateral estoppel will help us deal with the issue of other employees or former employees prosecuted for bribery when the corporation participates in local proceedings as a victim. I will conclude that when individuals related to corporations are prosecuted for bribery and this issue as such as litigated and decided locally —whatever the result— prosecution of the corporation in the us should be precluded.

A. Generalities and the "Same Offense" Requirement

The United States Supreme Court has defined double jeopardy as "the right not to be placed in jeopardy more than once for the same offense"26. It has been characterized as a "vital safeguard in our society" and, as such, should not be applied narrowly because it would be "deprived of much of its significance"27. Therefore, its interpretation should be broad.

For the Double Jeopardy guarantee to be activated, a corporation or individual must be in present jeopardy, after already having been placed in jeopardy for the same offense. Therefore, it is important to keep in mind that Double Jeopardy only attaches once the jury has been impanelled and sworn (in a jury trial) or once the first witness has been sworn (in a bench trial). Thus, a defendant will be considered to have been placed "in jeopardy" when trial began against him in a previous occasion. In consequence, Double Jeopardy does not intend to bar multiple investigations, because a mere investigation does not constitute jeopardy28.

Double Jeopardy bans relitigation when there has been a previous acquittal or conviction. An important consequence of this assertion is that it precludes the possibility of appealing an acquittal. A verdict of acquittal is final and cannot be revised without putting a person twice in jeopardy, even if the acquittal was based in "egregiously erroneous foundations"29. A judicial decision or resolution in favor of a defendant will be considered an acquittal only when it evaluates evidentiary material and concerns factual elements of the offense30. Other types of resolutions (such as mistrials) are generally not considered acquittals31. Nonetheless, if an acquittal was obtained by bribing or coercing the decision-maker, Double Jeopardy will not attach32. Also, Double Jeopardy protections may be lifted for manifest necessity, like for example, when there is a hung jury33.

Thus, the Fifth Amendment provides protection against a second prosecution for the same offense after there has been an acquittal or a conviction. It also safeguards citizens against multiple or cumulative punishments for the same offense34. However, separate crimes do not need to be identical in their constituent elements in order to be regarded as "the same offense". The "Blockburger test" has been established for determining whether two offenses are sufficiently distinguishable so as to permit multiple prosecutions35. When an act violates two distinct statutes, the issue is "whether each provision requires proof of an additional fact which the other does not"36 "notwithstanding a substantial overlap in the proof offered to establish the crimes"37.

Therefore, the relevant issue for this paper is whether the crime of bribery in any of the local jurisdictions in Latin America is the "same offense" as the offenses (anti-bribery provisions) described in the FCPA. Before analyzing this issue, we should keep in mind that all jurisdictions in the Latin American region describe substantially the same conduct when punishing bribery of public officials. Hence, the crime of bribery is essentially identical across Latin America.

Continuing with the issue stated above, my contention is that the local crime of bribery in a Latin American jurisdiction is the same offense as the pertinent anti-bribery provisions in the FCPA. I advance two main arguments in support of this assertion. First, conducts prohibited under the FCPA identify in their "core" with the Latin American crime of bribery. The Supreme Court held in Kay that "when the FCPA is read as a whole, its core of criminality is seen to be the bribery of a foreign official to induce him to perform an official duty in a corrupt manner"38. Thus, an individual or corporation convicted or acquitted by local authorities in Latin America could not be submitted to a successive prosecution in the United States, since the "core" of the local offense of bribery and the FCPA is identical, and hence, the offenses are the "the same".

In second place, if the above reason is not admitted, it could be understood that the FCPA contains a "greater" offense because it includes more elements such as the "business nexus" requirement. The Fifth Amendment also bans multiple punishments and/or prosecutions for a lesser offense when double jeopardy has already attached for the greater offense, and vice versa. The greater/lesser offense relationship means that the lesser offense only requires proof of elements presently included in the greater offense, while in turn, the greater offense, requires proof of additional elements. In other words, the lesser offense is "included in" the greater offense39. In fact, the Supreme Court has noted that "the sequence" is immaterial. Therefore it is as objectionable for the prosecution of a greater offense to come after the proceeding for the lesser offense, as it is for the reverse situation to take place. The Court has also specified that the rule about greater and lesser offenses has exceptions, when the additional elements of the greater offense had not taken place or had not been discovered before the trial of the lesser offense began40.

According to what the Supreme Court established in Brown "the greater offense is therefore by definition the 'same' for the purposes of double jeopardy as any lesser offense included in it"41.

Within the rationale of greater and lesser offenses, bribes in Latin America could be construed as a "lesser" offense. Bribes under local law would require no proof beyond that which is required for a conviction of the greater FCPA offense. Therefore, if an individual or corporation was tried in Latin America for a bribe of a public official, he could not again be prosecuted in the United States because all the elements of the local crime would be included in the FCPA anti-bribery provisions.

The conclusions under either reasoning offered above are only relevant when the corporation itself is deemed to be the "agent" of the crime, and thus its legal representative is locally prosecuted and judged, because double jeopardy would attach to the corporation itself, awarding protection under the Fifth Amendment. This is important because the doj should decline prosecution against a corporation under the FCPA as a binding matter of law. Thus, within the arguments advanced in this paper, a successful foreign criminal proceeding would not only receive consideration as a "mere factor" when the doj is making a discretional decision.

As epilogue, I would like to mention that scholars have noted that Congress was alerted since the first days of the FCPA that the intended extraterritorial reach could bring as a result double jeopardy issues42.

B. The Dual Sovereignty Issue

Thanks to issues brought before the Supreme Court regarding successive state and federal prosecutions, based upon the same conduct, the dual sovereignty doctrine has been widely developed43. When a defendant in a single act violates the "peace and dignity" of two sovereigns by breaking the laws of each, he has committed two distinct "offenses". "In recognition of this fact, the Court consistently has endorsed the principle that a single act constitutes an 'offense'' against each sovereign whose laws are violated by that act"44. In the case of the Federal Government and the States the Court has held that the power of the ladder to prosecute derives from its own inherent sovereignty, not from the Federal Government. Among States the doctrine applies equally since they are no less sovereign with respect to each other than they are in regard to the Federal Government.

Therefore, prosecution by dual sovereignties is not barred by the Double Jeopardy Clause. In applying this doctrine it must be ascertained whether the entities that seek prosecution for the same conduct are in fact "separate sovereigns"45. The application of the doctrine depends on whether the prosecutorial power of each entity derives from independent sources of authority. The issue turns on "the ultimate source of the power under which the respective prosecutions were undertaken"46.

In consequence, it may be obvious to assert that the United States and nations in Latin America are different sovereignties. But, are they? The question is relevant because the us Supreme Court has argued in certain cases, that some entities do not have independent sources of authority47.

"Sovereignty", according to the Supreme Court, implies an independent source of power and authority. Can it be affirmed today, that a country that has entered into an international Treaty which demands enactment of statutes punishing certain conducts (such as the Treaties I will mention below with respect to public corruption), is completely autonomous to criminalize such conduct in the way it deems more appropriate? I argue it is not. It is precisely the essence of international law that nations give away or sacrifice part of their autonomy in order to assume certain obligations. My contention is that today nations (especially in the us/Latin American context) share sovereignty (authority and power) when it comes to the battle against transnational corruption, as a result of the common effort undertaken by the international legal community —through a number of instruments— to punish bribery of foreign public officials.

As I have explained supra § II., the United States and most of the jurisdictions in Latin America have signed the oecd Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions. The Convention's binding force is such upon the sovereignty of the United States, that the FCPA was reformed in 1998 when the Senate ratified it. This demonstration of binding force is also shown in the legislative history of other parties to the Convention. For example Mexico, among other Latin American jurisdictions, has also adjusted its laws to the standards set forth by the Convention.

We must also keep in mind that the United States and all Latin American jurisdictions are members of the United Nations and therefore all bound by the terms of the Convention of the United Nations Against Corruption.

Furthermore, they are all bound by the Inter-American Convention Against Corruption produced within the Organization of American States (oas). Thus, in the Inter-American context, jurisdictions share, as a matter of international law, power and authority with respect to the prosecution of public corruption.

I do not pretend to assert that the rules set forth in these three international instruments are identical to the laws finally enacted in the United States and in Latin America to combat corruption. Nonetheless those instruments, without a doubt, generated the obligation for those countries (the state-parties) to create laws to punish and prosecute bribery of public officials, even if the final provisions turned out to be, to a certain degree, dissimilar.

Furthermore, the global international community, even beyond the American region, is also more than engaged in the fight against corruption. Therefore it could be argued that it has become an international imperative (ius cogens) to participate in such an effort, strengthening the argument in favor of a shared sovereignty. Europe48 has multiple Conventions regarding corruption and the African Union executed the Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption. The ladder is especially important to take into account for the purpose of this paper, because it expressly forbids in Article 13 for a person to be tried twice for the same offense.

Consequently, can it really be held that nations are free to exercise their sovereignty indistinctly and without regard to those instruments? Could a country decide not to enact statutes against corruption without violating its international obligations? It is my contention that they do not have the independent power to disregard their international obligations and thus, are not completely sovereign. Their sovereignty is, in fact, shared because the source of power and authority to create offenses comes precisely from the instruments to which nations are parties of, and by which they have agreed to be mandatorily bound. The power they exercise when creating corruption related offenses is in reality the exercise of power conveyed upon them by those instruments in light of the obligations such instruments impose. States in the American region share a commitment and therefore, have a common power to defeat transnational corruption.

In conclusion, I claim that with respect to laws against public corruption, the us and most part of Latin America as a matter of law, share their sovereignty, as they are in fact part of the same international effort —reflected in at least the three international instruments mentioned above— dedicated to fight against bribery of public officials. Therefore, the dual sovereignty doctrine cannot be argued in order to lift Double Jeopardy protections for conducts tried in Latin America and later prosecuted in the United States.

The underlying rationale I propose for applying the dual sovereignty doctrine in FCPA related prosecutions, finds scholarly support. Some authors reject the idea of lifting Double Jeopardy protection in cases in which the same crime is committed in two or more countries49. This issue is currently one of the greatest concerns of some scholars around the world. For example, Low50 criticizes the Inter-American anticorruption system for disregarding the concern expressed by the Juridical Committee Report of the oas about the eventual violations of double jeopardy and for not attaining a consensus with respect to "non bis in idem"51. Similarly, Snider & Kidane52 disapprove lacac's and uncac's omission in prohibiting double jeopardy expressly, while commending the au Corruption Convention on this matter53.

Thus far, I have argued that double jeopardy attaches to corporations when their legal representatives in foreign jurisdictions, especially in Latin America, are prosecuted for bribery. The issue I will address in this section is about what happens when it is another employee of the corporation the one that is prosecuted locally and the corporation just participates as a victim. To solve this inquiry I propose we look to collateral estoppel.

According to the principle of collateral estoppel (also called issue preclusion) if "an issue of ultimate fact has once been determined by a valid and final judgment, that issue cannot again be litigated between the same parties in any future lawsuit"54. The principle has full application in criminal law and it is embodied in the Double Jeopardy Clause55. When applying it, a Court must look to all the circumstances in the proceedings and the evidence to conclude if a "rational jury could have grounded its verdict upon an issue other than that which the defendant seeks to foreclose from consideration"56.

Further Supreme Court cases like Dowling57 have held that a defendant's right to issue preclusion only applies "when the relevant issue is ultimate in the subsequent prosecution, this is, when it must be proven beyond a reasonable doubt "58. Other courts have held —to sum up the ideas expressed above— that the doctrine of collateral estoppel may be used to preclude re-litigation of issues in a subsequent proceeding when: (1) the party against whom the doctrine is asserted was a party to the earlier proceeding; (2) the issue was actually litigated and decided on the merits; (3) the resolution of the particular issue was necessary to the result; and (4) the issues are identical59.

Even though some resist the idea that under us law the doctrine of international double jeopardy could apply, scholars support the argument that "collateral estoppel is applicable in criminal cases only when double jeopardy is not. And in respect of issues resolved in foreign proceedings, provided the foreign proceedings were fair, impartial, and compatible with us conceptions of due process of law, facts resolved in foreign courts can have a preclusive effect on subsequent proceedings in us courts" 60.

Consequently, I claim that in the case of employees of corporations that are prosecuted by foreign authorities —only when the company presents itself as a victim to actively advance the proceedings— once the issue of the bribe is decided, it could not again be re-litigated in the us I advance the following arguments in support of my claim:

- The corporation will be a party in the Latin American proceeding —a victim— and thus, the first requirement for applying collateral estoppel will be satisfied.

- The issue actually litigated and decided locally will be the bribe, as it will be under a doj investigation, thus, satisfying the second estoppel requirement.

- If the doj prosecuted the case again, this time against the corporation, it would litigate again the same (identical) issue, and would need to prove it beyond reasonable doubt. As we know from Kay, the core of the fcpa criminal conduct is the bribe. Therefore, the core —the bribe— is the necessary or "ultimate issue" of the litigation abroad and in the us.

- A successful criminal prosecution in Latin America only has two possible results: a conviction or an acquittal. Thus, in the us after the termination of a proceeding abroad, there are only two possible scenarios: a) In case the employee was convicted, if the doj prosecutes a corporation, then it will prosecute a recognized victim in another jurisdiction, or b) In case the employee was acquitted, if the doj prosecutes a corporation, then it will prosecute a crime that never took place. In either case, it is forbidden, as matter of law under collateral estoppel, to prosecute the corporation. Whatever the result (a conviction or an acquittal), the issue of "the bribe" will have been dealt with —litigated and decided— locally. Hence, a later prosecution in the us would violate collateral estoppel.

Finally, I present two closing remarks. First, there is another international dimension that is worth pointing out: citizens of nations that recognize the jurisdiction of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights are protected by "non bis in idem". Thus, successive trials in the American region could violate a human right guarantee against double jeopardy.

Second, the act of state doctrine could be used to support the notion that the doj must deem valid any and all decisions made by foreign jurisdictions when deciding whether to pursue an fcpa investigation and thus terminate any us proceedings, because "the act of state doctrine does not establish an exception for cases and controversies that may embarrass foreign governments, but merely requires that, in the process of deciding, the acts of foreign sovereigns taken within their own jurisdictions shall be deemed valid"61.

IV. Practical application and conclusion

To conclude we can say that a corporation may be prosecuted in a Latin American jurisdiction, as if it was the agent of an offense, through its legal representative, or it can participate as a victim against an employee or former employee that has engaged in a corrupt practice. In either case, locally, a criminal proceeding will take place and an individual with be convicted or acquitted. We must keep in mind this paper has focused primarily on bribery investigations in Latin America.

If a legal representative of a corporation is convicted abroad for the bribe of a public official, a corporation cannot be again prosecuted in the United States for an FCPA violation. The corporation is protected by the prohibition against Double Jeopardy because the foreign and us proceedings would be based on the "same offense". Furthermore, Double Jeopardy protections would apply since there are not two independent sovereignties involved, but only one common power and authority against transnational corruption, shared by the United States and the majority of Latin American jurisdictions.

If another employee of the corporation is prosecuted because the corporation itself is not treated locally as the agent of the bribe, and the corporation participates as a victim, that individual too, will be either convicted or acquitted. The issue of the bribe will be, thus, subject to a final judicial resolution. That bribe could not again be subject to prosecution within the us because collateral estoppel would apply, and therefore, any later criminal proceeding would be precluded.

These conclusions deal with binding legal matters and hence, do not constitute a mere factor to be taken into account by the doj when making the discretional decision of declining charges.

The issue now before us, is whether there are any practical applications in FCPA litigation of the above stated conclusions. In my opinion, corporations, as a matter of strategy, should assume an extremely active participation in foreign prosecutions, so as to assure a conviction or acquittal in the least time possible. When their representatives are defendants, they should procure the advancement of the proceedings by all possible legal means; and as victims against employee(s) or former employee(s), they should seek a decision with absolute diligence. In both cases, securing a final judicial resolution will activate double jeopardy or collateral estoppel.

Why seek a decision abroad first, to then preclude the doj from bringing charges before us Courts? There are a number of reasons for suggesting this strategy.

1) Latin American jurisdictions all require subjective responsibility (a notion of culpability much broader than "mens rea") in order to convict. It is extremely difficult to draw a parallel between mens rea in the Anglo-American tradition and subjective responsibility in Latin American legal history however, it is valid to claim that the functional equivalent of the requisite state of mind in bribery crimes in the region is "purpose" under the us Model Penal Code62. Bribery of public officials is always a willful and intentional crime in Latin America63. Therefore, in Latin America, convictions will be harder to secure against individuals.

2) Subjective responsibility as doctrinally understood in civil law systems would allow defenses such as the "existence of compliance program"64 Substantive criminal law in the continental European/Latin American historical tradition, demands that an individual can only be convicted when he consciously intends to carry out the prohibited conduct. Thus, if an effective and well organized compliance program is set in place, by definition, no subjective responsibility will be present. On the contrary, in the us such an affirmative defense is not expressly recognized under the FCPA. Many have endorsed its inclusion in the statute, but nonetheless, it still remains just another factor for the doj to assess when deciding whether to charge or subscribe an agreement.

3) Fines after a conviction will never be as steep as the amounts paid in agreements with the doj and the sec. Recent fines and settlements paid to the doj and the sec are considerably high65. In Latin American Penal Codes, fines are established within the text of the offense itself (so there is virtually no judicial discretion) and there is not one single example of a bribery offense with a fine66 that comes near to the amounts reported recently by us FCPA enforcement agencies.

4) Legal fees for attorneys are lower. 5) An indictment will not have for the corporation (precisely because, as I have explained, corporations are not criminally liable), the dramatic consequences established under us law, such as "suspension or debarment from contracting with the federal government, cross-debarment by multilateral development banks, and the suspension or revocation of certain export privileges"67. Nonetheless, we must not disregard that many Codes in Latin America now allow consequences against a corporation after the termination of a criminal proceeding. 6) An active cooperation with local authorities abroad, will at least award points of cooperation before the doj in an FCPA prosecution according to the usam.

This strategy would only come into play if a corporation actually takes part in the proceedings through its representative/defendant or as a victim. Otherwise the entity will just be a third party with no bearing over the results, the celerity and the effectiveness of the proceedings. Nevertheless, in any case, the results of the local prosecution will, as a matter of law, produce double jeopardy and collateral estoppel effects.

In conclusion I propose that, as a matter of strategy, corporations with FCPA issues should actively seek to advance proceedings conducted abroad, especially in Latin America, with the purpose of securing a quick, fair and final judgment. In any capacity in which they are acting, beneficial consequences will arise for the corporation, regarding double jeopardy, collateral estoppel, or, at the very least, points leading towards a more favorable agreement with the doj for collaborating (as a "defendant" through its legal representative or as a victim) with local authorities.

Pie de página

1S. Rep. No. 95-114, at 4. At http://www.justice.gov/criminal/fraud/fcpa/history/1977/senaterpt-95-114.pdf and H. R. Rep. No. 95-640, at 4-5. At http://www.justice.gov/criminal/fraud/fcpa/history/1977/houseprt-95-640.pdf (1977) "The payment of bribes to influence the acts or decisions of foreign officials, foreign political parties or candidates for foreign political office is unethical. It is counter to the moral expectations and values of the American public. But not only is it unethical, it is bad business as well. It erodes public confidence in the integrity of the free market system. It short-circuits the marketplace by directing business to those companies too inefficient to compete in terms of price, quality or service, or too lazy to engage in honest salesmanship, or too intent upon unloading marginal products. In short, it rewards corruption instead of efficiency and puts pressure on ethical enterprises to lower their standards or risk losing business".

2A resource guide to the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. By the Criminal Division of the us Department of Justice and the Enforcement Division of the US. Securities and Exchange Commission. At http://www.justice.gov/criminal/fraud/fcpa/guide.pdf

3us Sec. and Exchange Commission, Report of the Securities and Exchange Commission on Questionable and Illegal Corporate Payments and Practices, 2-3 (Author, 1976).

4Supra note 2, at 3-4.

5New York Central & Hudson River Railroad vs United States, 212 us 481 (1909).

6Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. 15 USC §§ 78dd-1, 78dd-2, 78dd-3, 78m, 78ff.

7Óp. cit.

8us Dept. of Justice, us Attorneys' Manual [hereinafter usam]. At http://www.justice.gov/usao/eousa/foia_reading_room/usam/ (2008); see also Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure.

9Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, supra note 6.

10http://www.justice.gov/criminal/fraud/fcpa/

11OECD. Country Reports on the Implementation of the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention. At http://www.oecd.org/daf/anti-bribery/countryreportsontheimplementationoftheoecdanti-briberyconvention.htm

12Appendix. Attached to this essay is a chart portraying legal and normative information about the majority of countries in Latin America. Some countries, especially in the Caribbean region are left out.

13See Appendix.

14Declaration of Basic Principles of Justice for Victims of Crime and Abuse of Power. GA Res. 40/34, UN Doc. A/RES/40/34 (Nov. 29, 1985). This international instrument provides a fairly good and widely accepted definition of victims and their rights. In general it is said that victims have three rights: truth, justice and reparation. This conception of victims can be found in the relevant articles of all the Codes cited in the Appendix.

15See Appendix.

16See usam § 9.27-220, supra note 8. "Grounds for commencing or Declining Prosecution. A. The attorney for the government should commence or recommend Federal prosecution if helshe believes that the person's conduct constitutes a Federal offense and that the admissible evidence will probably be sufficient to obtain and sustain a conviction, unless, in hisl her judgment, prosecution should be declined because: 1. No substantial Federal interest would be served by prosecution; 2. The person is subject to effective prosecution in another jurisdiction; or 3. There exists an adequate non-criminal alternative to prosecution".

17"Initiating and Declining Charges - Prosecution in another Jurisdiction. A. In determining whether prosecution should be declined because the person is subject to effective prosecution in another jurisdiction, the attorneyfor the government should weigh all relevant considerations, including: 1. The strength of the other jurisdiction's interest in prosecution; 2. The other jurisdiction's ability and willingness to prosecute effectively; and 3. The probable sentence or other consequences if the person is convicted in the other jurisdiction. B. Comment. In many instances, it may be possible to prosecute criminal conduct in more than one jurisdiction. Although there may be instances in which a Federal prosecutor may wish to consider deferring to prosecution in another Federal district, in most instances the choice will probably be between Federal prosecution and prosecution by state or local authorities. usam9-27.240 sets forth three general considerations to be taken into account in determining whether a person is likely to be prosecuted effectively in another jurisdiction: the strength of the jurisdiction's interest in prosecution; its ability and willingness to prosecute effectively; and the probable sentence or other consequences if the person is convicted. As indicated with respect to the considerations listed in paragraph 3, these factors are illustrative only, and the attorney for the government should also consider any others that appear relevant to hislher in a particular case. 1. The Strength of the Jurisdiction's Interest. The attorney for the government should consider the relative Federal and state characteristics of the criminal conduct involved. Some offenses, even though in violation of Federal law, are of particularly strong interest to the authorities of the state or local jurisdiction in which they occur, either because of the nature of the offense, the identity of the offender or victim, the fact that the investigation was conducted primarily by state or local investigators, or some other circumstance. Whatever the reason, when it appears that the Federal interest in prosecution is less substantial than the interest of state or local authorities, consideration should be given to referring the case to those authorities rather than commencing or recommending a Federal prosecution. 2. Ability and Willingness to Prosecute Effectively. In assessing the likelihood of effective prosecution in another jurisdiction, the attorney for the government should also consider the intent of the authorities in thatjurisdiction and whether thatjurisdiction has the prosecutorial and judicial resources necessary to undertake prosecution promptly and effectively. Other relevant factors might be legal or evidentiary problems that might attend prosecution in the other jurisdiction. In addition, the Federal prosecutor should be alert to any local conditions, attitudes, relationships, or other circumstances that might cast doubt on the likelihood of the state or local authorities conducting a thorough and successful prosecution. 3. Probable Sentence Upon Conviction. The ultimate measure of the potential for effective prosecution in another jurisdiction is the sentence, or other consequence, that is likely to be imposed if the person is convicted. In considering this factor, the attorney for the government should bear in mind not only the statutory penalties in the jurisdiction and sentencing patterns in similar cases, but also, the particular characteristics of the offense or, of the offender that might be relevant to sentencing. Helshe should also be alert to the possibility that a conviction under state law may, in some cases result in collateral consequences for the defendant, such as disbarment, that might not follow upon a conviction under Federal law".

18See Appendix.

19"Factors to be Considered. A. General Principle: Generally, prosecutors apply the samefactors in determining whether to charge a corporation as they do with respect to individuals". See usam 9-27.220 et seq. Thus, the prosecutor must weigh all of the factors normally considered in the sound exercise of prosecutorial judgment: the sufficiency of the evidence; the likelihood of success at trial; the probable deterrent, rehabilitative, and other consequences of conviction; and the adequacy of noncriminal approaches. See Óp. cit. However, due to the nature of the corporate "person" some additional factors are present. In conducting an investigation, determining whether to bring charges, and negotiating plea or other agreements, prosecutors should consider the following factors in reaching a decision as to the proper treatment of a corporate target: 1. The nature and seriousness of the offense, including the risk of harm to the public, and applicable policies and priorities, if any, governing the prosecution of corporations for particular categories of crime (see usam 9-28 400); 2. The pervasiveness of wrongdoing within the corporation, including the complicity in, or the condoning of, the wrongdoing by corporate management (see usam 9-28.500); 3. The corporation's history of similar misconduct, including prior criminal, civil, and regulatory enforcement actions against it (see usam 9-28 600); 4. The corporation's timely and voluntary disclosure of wrongdoing and its willingness to cooperate in the investigation of its agents (see usam 9-28 700); 5. The existence and effectiveness of the corporation's pre-existing compliance program (see usam 9-28 800); 6. The corporation's remedial actions, including any efforts to implement an effective corporate compliance program or to improve an existing one, to replace responsible management, to discipline or terminate wrongdoers, to pay restitution, and to cooperate with the relevant government agencies (see usam 9-28 900); 7. Collateral consequences, including whether there is disproportionate harm to shareholders, pension holders, employees, and others not proven personally culpable, as well as impact on the public arising from the prosecution (see usam 9-28 1000); 8. The adequacy of the prosecution of individuals responsible for the corporation's malfeasance; and 9. The adequacy of remedies such as civil or regulatory enforcement actions (see usam 9-28 1100). B. Comment: The factors listed in this section are intended to be illustrative of those that should be evaluated and are not an exhaustive list of potentially relevant considerations. Some of these factors may not apply to specific cases, and in some cases one factor may override all others. For example, the nature and seriousness of the offense may be such as to warrant prosecution regardless of the other factors. In most cases, however, no single factor will be dispositive. In addition, national law enforcement policies in various enforcement areas may require that more or less weight be given to certain of these factors than to others. Of course, prosecutors must exercise their thoughtful and pragmatic judgment in applying and balancing these factors, so as to achieve a fair and just outcome and promote respect for the law. In making a decision to charge a corporation, the prosecutor generally has substantial latitude in determining when, whom, how, and even whether to prosecute for violations of federal criminal law. In exercising that discretion, prosecutors should consider the following statements of principles that summarize the considerations they should weigh and the practices they should follow in discharging their prosecutorial responsibilities. In doing so, prosecutors should ensure that the general purposes of the criminal law—assurance of warranted punishment, deterrence of further criminal conduct, protection of the public from dangerous and fraudulent conduct, rehabilitation of offenders, and restitution for victims and affected communities—are adequately met, taking into account the special nature of the corporate "person".

20See usam § 9-28 700; § 9-28 900; and factor No. 8 in usam § 9-28 300.

21Standard § 3-3.9. aba Standards for Criminal Justice: Prosecution and Defense Function (3d ed., American Bar Association, 1993).

22Supra note 2, footnote No. 382.

23B. L. Garrett, Globalized Corporate Prosecutions, 97 Virginia Law Review, 1775, (2011).

24Grady vs. Corbin, 495 us 508 (1990).

25Benton vs. Maryland, 395 us 784 (1969).

26Green vs. United States, 355 us. 184, 198 (1957).

27Ibidem.

28Crist vs. Bretz, 437 us 28 (1978).

29Fong Foo vs. United States, 369 us 141 (1962); see also United States vs. Scott, 436 US 128 (1978).

30Sanabria vs. United States, 437 us 54 (1978).

31United States vs. Scott, 436 us 128 (1978).

32Aleman vs. Judges of the Circuit Court of Cook County. Court, 248 F.3d 604. 7th Cir. 2001.

33Oregon vs. Kennedy, 456 us 667 (1982).

34North Carolina vs. Pearce, 395 us 711 (1969); see also US vs. Wilson, 420 US 332 (1975) and Lange, 18 Wall. 163 (1874); re Nielsen, 131 us 176 (1889); United States vs. Gibert, 25 F.Cas. p. 1287 (No. 15 204) (ccd Mass.1834) (Story, J.); United States vs. Jorn, 400 us 470 (1971); Ashe vs. Swenson, 397 US 436 (1970) United States vs. Martin Linen Supply Co., 430 US 564 (1977).

35Blockburger vs. United States, 284 us 299 (1932).

36Ibidem, at 304.

37Iannelli vs. United States, 420 us 770 (1975).

38us vs. Kay, 359 F.3d 738, 761. 5th Cir. 2004.

39Harris vs. Oklahoma, 433 us 682 (1977); Garrett vs. United States, 471 us 773 (1985).

40Jeffers vs. us, 432 us 137 (1977).

41Brown vs. Ohio, 432 us 161, 168 (1977). See also Morey vs. Commonwealth, 108 Mass. 433, 434 (1871); J. Bishop, New Criminal Laws 1051 (8th ed. 1892); Comment, Twice in Jeopardy, 75 Yale LJ 262, 268-269 (1965); Gore vs. United States, 357 us 386 (1958); Bell vs. United States, 349 us 81 (1955); Gavieres vs. United States, 220 us 338 (1911).

42H. Lowell Brown, The Extraterritorial Reach of the US Government's Campaign Against International Bribery, 22 Hastings Int'l & Comp. L. Rev, 407 (1999).

43United States vs. Lanza, 260 us 377 (1922); Fox vs. State of Ohio, 46 us 410 (1847); Bartkus vs. People of State of Ill., 359 us 121 (1959), Abbate vs. United States, 359 us 187 (1959).

44Heath vs. Alabama, 474 us 82, 93 (1985). Justices Brennan and Marshal dissented and argued that the term "same offense" in the Constitution was being given a very narrow and restricted meaning. According to them, there is no evidence the Framers had in mind such a restrictive application.

45Waller vs. Florida, 397 us 387 (1970); Puerto Rico vs. Shell Co., 302 us 253 (1937); Grafton vs. United States, 206 us 333 (1907).

46United States vs. Wheeler, 435 us 313, 320 (1978).

47It is important to mention, that the Supreme Court has rejected the argument that if two entities have concurrent jurisdiction and pursue different interests, then the doctrine should be restricted only to cases when allowing both prosecutions is necessary for the satisfaction of the legitimate interests of both entities. That balancing approach, in opinion of the Court, cannot be reconciled with the dual sovereignty principle. Therefore, when two sovereignties are involved, both offenses are not the "same" under the meaning of the Fifth Amendment notwithstanding similarity (or difference) of interests, statutes and conduct.

48Convention Relative to the Fight Against Acts of Corruption in Which Agents of the European Communities or of the States that are Parties of the European Union, approved by the Counsel of the European Union on May 26, 1997; Convention on Criminal Law Against Corruption, approved by the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe of 1994; Convention on Civil Law About Corruption, approved by the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe, 1999.

49United States vs. Martin, 574 F. 2d 1359, 1360, 5th Cir. 1978. "The Constitution of the United States has not adopted the doctrine of international double jeopardy", citing Bartkus vs. Illinois, 359 us 121, 128 (1959)). See also United States vs. Jeong, 624 F.3d 706 5th Cir. 2010, and Chukwurah vs. United States, 813 F. Supp. 161 (edny, 1993).

50See L. A. Low, The Inter-American Convention Against Corruption: a Comparison with the United States Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, 38 Va. J. Int'l L. 243, 288-89 (1998): "This issue is thrown into sharp relief by the Convention's transnational bribery provisions. The Juridical Committee Report recommends that the states parties consider whether a person who has been convicted of bribery by the country of the government official in question can then be tried by the country of his nationality, or whether the principle of non bis in idem applies. Multilateral consensus on this issue would facilitate uniform application and enforcement of the Convention. Though the states parties could agree that non bis in idem does not apply (so long as it is not customary international law), considerations of efficiency and fairness suggest that only one country prosecute the alleged offender, with full assistance and cooperation provided by the other country(ies) involved, at least once there is substantial equivalence in the legal regimes of member states and in the capacity of countries to enforce their laws effectively. Until then, countries with strong enforcement capabilities will be reluctant to defer to countries that may not, for example, impose adequate penalties". On the other hand, scholars have commended the African approach to double jeopardy.

51"Non bis in idem" is the term used in the Latin American legal tradition to designate the prohibition against successive trials for the same offense. For the purpose of this paper, it is not inaccurate to claim that "non bis in idem" is the functional equivalent of double jeopardy in the Anglo-American tradition.

52T. R. Snider & W. Kidane, Combating Corruption Through International Law in Africa: a Comparative Analysis, 40 Cornell Int'l L.J. 691, 747 (2007): "Consistent with its rights approach, the AU Corruption Convention expressly prohibits double jeopardy. This prohibition, which the other two conventions omit, is particularly essential because the jurisdictional grounds that all the conventions create overlap significantly and a given set of circumstances could therefore give rise to multiple assertions of jurisdiction. Inevitably, that would lead to valid extradition requests that may not be refused even if it means that the accused would be subjected to double jeopardy. The assumption that the prohibition against double jeopardy does not apply when multiple sovereigns are involved may explain the iacac's and uncac's omission. However, the danger of subjecting an innocent person to judicial ordeals in multiple states or subjecting a person to multiple punishments for the same offense seems to outweigh benefits that omission of the prohibition may bring. As such, the AU Corruption Convention's approach to double jeopardy is not only fair and desirous but also in line with its rights and good governance approach. Compromising fundamental principles of justice for the benefit oflaw enforcement is more dangerous than illicit benefits and, as such, should not be encouraged".

53It is very important to note that some cases have expressly rejected the idea of international double jeopardy. However, in my opinion, the arguments presented in this paper are different than the ones that have been submitted thus far to the Courts. See United States vs. Martin, 574 F.2d 1359, 1360, 5th Cir. 1978. "The Constitution of the United States has not adopted the doctrine of international double jeopardy", citing Bartkus vs. Illinois, 359 us 121, 128 (1959)). See also United States vs. Jeong, 624 F.3d 706, 5th Cir. 2010, and Chukwurah vs. United States, 813 F. Supp. 161 (edny, 1993).

54Ashe vs. Swenson, 397 us 436, 443 (1970).

55See United States vs. Oppenheimer, 242 us 85 (1906).

56Id. at 397 us 444.

57See Dowling vs. United States, 493 us 342 (1990).

58United States vs. Bailin, 977 F. 2d 270, 280-281, 7th Cir. 1992.

59See Kunzelman vs. Thompson, 799 F.2d 1172, 1176, 7th Cir. 1986 see also Kraushaar vs. Flanigan, 45 F.3d 1040, 7th Cir. 1995.

60A. S. Boutros & T. Markus Funk, "Carbon Copy" Prosecutions: a Growing Anticorruption Phenomenon in A Shrinking World, U. Chi. Legal F., 259-294 (2012). These authors resist the idea that under US law the doctrine of international double jeopardy could apply but they have noted that under other jurisdictions double jeopardy could attach. The uk for example applies double jeopardy in a broader manner focusing more on the underlying facts used to support the offense, and has limited its prosecutions in the past, when other nations have first asserted their jurisdictions. But even these scholars recognize that collateral estoppel has fewer limitations and could be used in international contexts.

61W. S. Kirkpatrick & Co., Inc. vs. Envtl. Tectonics Corp., Int'l, 493 us 400, 409-10 (1990).

62Model Penal Code.

63See Appendix.

64M. Koehler, Revisiting a Foreign Corrupt Practices Act Compliance Defense, Wisc. Law Rev, 609, 659 (2012). "A company's pre-existing fcpa compliance policies and procedures and its good-faith efforts to comply with the fcpa should be relevant as a matter of Jaw-not merely in the opaque, inconsistent, and unpredictable world of doj decision making-when a nonexecutive employee or agent acts contrary to those policies and procedures. An fcpa compliance defense would not eliminate corporate criminal liability under the fcpa or reward 'fig leaf or 'purely paper' compliance. Rather, an fcpa compliance defense, among other things, will better incentivize more robust corporate compliance, reduce improper conduct, and further advance the fcpa s objective of preventing bribery of foreign officials. The time is right to revisit an fcpa compliance defense".

65A resource guide to the us Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. By the Criminal Division of the us Department of Justice and the Enforcement Division of the us Securities and Exchange Commission. At http://www.justice.gov/criminal/fraud/fcpa/guide.pdf.

66See Appendix.

67Supra note 65, pp. 69-70. "In addition to the criminal and civil penalties described above, individuals and companies who violate the fcpa may face significant collateral consequences, including suspension or debarment from contracting with the federal government, cross-de-barment by multilateral development banks, and the suspension or revocation of certain export privileges".