Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

International Law

Print version ISSN 1692-8156

Int. Law: Rev. Colomb. Derecho Int. no.25 Bogotá July/Dec. 2014

https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.il14-25.bJCI

BRAZILIAN JUSTICE CONFIDENCE INDEX - MEASURING PUBLIC PERCEPTION ON JUDICIAL PERFORMANCE IN BRAZIL*

ÍNDICE DE CONFIANZA EN LA JUSTICIA EN BRASIL. MIDIENDO LA PERCEPCIÓN PÚBLICA ACERCA DE LA ADMINISTRACIÓN DE JUSTICIA EN BRASIL

Luciana Gross Cunha**

Fabiana Luci de Oliveira***

Rubens Eduardo Glezer****

*This study was made possible by the financial support of the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), of Canada, under the project Global Administrative Law: Improving Inter-institutional Connections in Global and National Regulatory Governance. Project number: 106812-001.

**Luciana Gross Cunha is Master and PhD in Political Science. Assistant Dean on Graduate Affairs and Professor at Fundação Getulio Vargas Law School in São Paulo, Brazil (FGV Direito SP). Responsible for coordination of the Brazilian Justice Confidence Index, an index published every semester which identifies the perception of Brazilian people's conidence in the Courts. Contact: Luciana.Cunha@fgv.br

***Fabiana Luci de Oliveira is PhD and Professor of Sociology at UFSCar (Federal University of São Carlos). CNPq Researcher. Contact: fabianaluci@ufscar.br

****Rubens Eduardo Glezer is Professor of specialization courses, researcher of the Center for Justice and Constitution and also Coordinator of the Supreme Court under Scrutiny project in FGV Direito SP. Professor at Faculdade de Direito de São Bernardo do Campo. PhD Candidate at USP, Master by FGV Direito SP and Graduated by PUC-SP Law Schools. Contact: rubens.glezer@fgv.br

Reception date: May 30th, 2014 Acceptance date: June 30th, 2014 Available Online: September 30th, 2014

To cite this article / Para citar este artículo

Cunha, Luciana Gross; Oliveira, Fabiana Luci de & Glezer, Rubens Eduardo, Brazilian Justice Confidence Index - Measuring Public Perception on Judicial Performance in Brazil, 25 International Law, Revista Colombiana de Derecho Internacional, 445-472 (2014). http://dx.doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.il14-25.bJCI

Abstract

The goal of the paper is to describe the design, development and consolidation of a measure method for the public perception ofjudicial performance in Brazil —the Brazilian Justice Confidence Index (JCIBrazil). Since April 2009, JCIBrazil has been published quarterly, amounting to twelve waves. The overall results point to a trend of poor assessment of the judiciary as a public service provider so that its slowness in response, its high cost and the difficult to use it. Although we have these results, the Brazilian policymakers should rely more closely on those statistics in order to align public policies to the improvement of the system. Attention must be given not only to the production of studies, research and data on the justice system, but also to the use and application of studies results and data.

Keywords: indicator; index; confidence; justice; judiciary; policy making; Brazil

Resumen

El objetivo de este articulo es describir el diseño, desarrollo y consolidación de un método de medición de la percepción pública de la actuación judicial en Brasil —el Indicador de Confianza en la Justicia Brasileña (JCIBrazil). Desde abril de 2009, JCIBrazil ha publicado trimestralmente y ha superado las veinte entregas. Los resultados generales apuntan a una tendencia a la mala evaluación del poder judicial como un proveedor de servicios públicos en cuanto a su lentitud en la respuesta, su alto costo y su difícil uso. A pesar de contar con estos resultados, quienes están encargados de generar políticas deben basarse en mayor medida en esas estadísticas con el fin de alinear las políticas públicas y asi mejorar el sistema. Se debe prestar atención no solo a la producción de estudios, investigaciones y datos sobre el sistema de justicia, sino también a la utilización y aplicación de los resultados de estudios y de los datos.

Palabras clave: indicador; confianza; justicia; poder judicial; políticas públicas; Brasil

SUMMARY

Introduction.- I. The índex design.- II. The índex development.- III. The índex consolidation.- IV. Potential for collaboration to public policy.- Bibliography.

Introduction

The goal of this paper, within the Reshaping Global Governance project, is to describe the design, development and consolidation of a measure method for the public perception of judicial performance in Brazil —the Brazilian Justice Confidence Index (JCIBrazil).

The effectiveness of the rule of law is one of the key factors behind any country's economic and social development. Thus, measuring judicial performance is a good way of measuring the effectiveness of the rule of law in a country, and therefore to obtain an indicator of a country's democracy quality.1 We share with Kevin Davis, Benedict Kingsbury and Sally Engle Merry (2011)2 the concept of indicators as a technology of global governance, that is, the idea that indicators may have effects on global governance.

And when we take into account the political context of most Latin American countries, where the judiciary has been a vital part of the emergence and consolidation of democracy, as those countries moved from military and authoritarian regimes to democracy over the last two decades, being a vital locus for deciding and solving disputes that arise in society, business, economy and politics, the need for such an indicator to measure judiciary performance strengthens. The measure of judiciary performance is even more significant in most Latin American countries where, during the transition from military and authoritarian to democratic regimes since the early nineties, the judiciary has been a central part of development and consolidation of the democratic process, becoming an essential locus for dispute resolution regarding the social, business, economic and political arenas. The impartial and fair application of law demands a legitimate, independent and effective judiciary. There are different ways of measuring judicial performance. Considering tangible data, international bodies such as ceja,3 list the need to consider variables like the number of cases initiated, pending and decided per year in courts, the average duration of cases, the number ofjudges per inhabitants, caseload per judge, cost per case, among others.4 Although essential, most of that information covers only the aspect of efficiency, and none is appropriate to provide objective data on the evaluation of the judiciary in terms of independence and access. Neither is able to indicate the motivations of citizens to use the judiciary as a channel for conflict resolution nor their trust in the institution.

Another international body, the International Consortium for Court Excellence, ICCE, proposed the International Framework for Court Excellence, in 2008. According to ICCE, the framework "represents a resource for assessing a court's performance against seven detailed areas of court excellence and provides clear guidance for courts intending to improve their performance."5 Among more objective measures of efficiency, it proposed more subjective measures based on public perception, including client needs and satisfaction as well as public trust and confidence.

Besides researches made by organizations, an academic study that accomplished data collection on the dimensions of judiciary independence, access and efficiency is the one made by Joseph L. Staats, Shaun Bowler & Jonathan T. Hiskey.6 The authors proposed a measure of judicial performance composed of five variables: level of independence, accountability, efficiency, effectiveness and accessibility. Those variables were assessed in terms of public perception of legal experts in seventeen selected countries.

The variable judicial independence refers both to the insulation from undue political influence and to the judge's ability of impartial decision-making in individual cases —they look at Supreme Court Justices and trial courts. The variable efficiency refers to the judicial system's ability to process cases without excessive delays. Access denotes the availability of equitable access to care for all citizens, regardless of socioeconomic status, race or geographic location.7 Effectiveness regards the ability to enforce civil liberties and human rights, considering the availability of viable enforcement mechanism of censoring and penalties. And finally, accountability, which is the subjection of the judiciary to the rule of law and transparency of its actions, including the perception on honesty of judicial system, and performance of Supreme Court justices and trial courts judges.

The authors surveyed seventeen Latin American countries, interviewing legal experts,8 and developed an index based on the previously described five variables.

The index ranges from 1 (worst performance) to 6 (best performance). Brazil ranks 4.54 (the second best performance, being Nicaragua the first, with 4.86. Uruguay is the worst with 2.73).

JCIBrazil dialogs with Staats, Bowler and Hiskey dimensions, but adopts a different methodology (since it is not an expert-based but a population-based survey). It is being run in Brazil since April 2009 and was in its 12th edition in December 2012. The context of its emergence is a sequence of studies and reports that rated the Brazil's judicial system amongst the most inefficient, iniquitous and corrupt in the world —which means it was not being effective.9 According to the United Nations, Brazil's judicial system was difficult to access and, when it was accessed, offered responses excessively slowly:

The report identifies the system's main shortcomings as follows: problems with access to justice, its slowness and notorious delays (...) a large proportion of the Brazilian population, for reasons of an economic, social or cultural nature or social exclusion, finds its access to judicial services blocked or is discriminated against in the delivery of those services [...] Delays in the administration ofjustice are another big problem, which in practice affects the right to judicial services or renders them ineffective. Judgments can take years, which leads to uncertainty in both civil and criminal matters and, often, to impunity.10

It is no novelty that judicial systems all around the world have been under severe public scrutiny in the past decades, with many authors suggesting a diagnosis of crisis, pointing that Judiciaries in different parts of the globe are ineffective, expensive, slow and incapable of responding to demands that affect the daily lives of ordinary citizens.

Despite all the diagnosed problems, when we look at the Brazilian case, there is a continuing high rate of litigation in courts with a growing trend. Official statistics show that the total number of new cases in the state jurisdiction multiplied almost by five in two decades, going from 3.6 million in 1990 to 17.7 million in 2011.11 This growth is significantly greater than the observed growth in the population.

Given the scenario those studies portrayed, it was necessary to build a systematic, detailed, and continuous measurement of the legitimacy and effectiveness of Brazil's judiciary, exposing the overall public perception and confidence in the country's judicial system. This need led to the creation of JCIBrazil in 2009.

I. The index design

The index JCIBrazil is a measure of how much people trust judiciary in Brazil. It is built based on a summary of variables that are shown —by the specialized literature— to influence public confidence in courts and in people declared level of confidence in the judiciary.

We have opted to center in the concept of trust because of it essentiality to the evaluation of an institution performance. Trust reduces the uncertainty and complexity of our social world and increases the predictability, and thus the tendency to cooperation, once individuals can expect that institutions will act according to its functions.12

There is an extensive literature on how to measure public confidence in institutions and particularly in the Judiciary.13 But as Ryan Salzman and Adam Ramsey say, the development of theories explaining public confidence in the judiciary has largely been developed and applied to the European and North

American contexts. Salzman and Ramsey applied those theories in ten Latin American countries (Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, and Colombia, Chile and Uruguay) using survey data from the Americas Barometer, by the Latin American Public Opinion Project, LAPOP, 2006 dataset. Results have shown that public perception on judiciary is influenced mainly by perception on institutional quality, individual experiences, and personal attitudes.14

And when it comes to individual experiences, literature indicates that perceptions of those who litigate are influenced mostly by how they are treated in courts, if the procedures seemed fair, more than to a possible favorable or unfavorable result in the case outcome.

Based on that literature and discussion, JCIBrazil was built taking into account factors that lead people to use (or not) and trust (or not) the judicial system. The index works with five dimensions: efficiency (speed), responsiveness (competence), accountability (impartiality), independence (from external political influence) and access (ease of use and costs). The ultimate question this indicator seeks to answer is how effective the judiciary is in guaranteeing "justice" for individuals in Brazil in the eyes of the population.

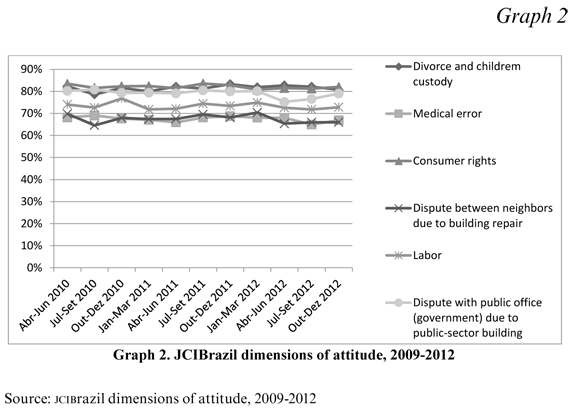

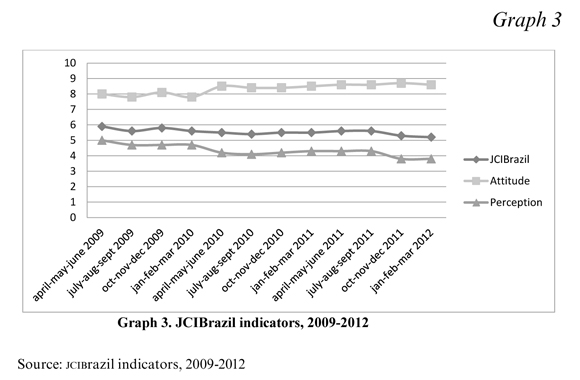

JCIBrazil is composed of two sub-indexes: (i) an index of perception —how the general public perceives the various dimensions of the judiciary as a public service provider— and (ii) an index of attitude —what are the attitudes and beliefs of the general public regarding the role of judiciary in solving conflicts.

The index of perception is based on a set of nine questions derived from the five dimensions posited by Staats, Bowler and Hiskey, covering (i) trust, (ii) speed in deciding conflicts, (iii) cost of access (iv) ease of access, (v) independence, (vi) honesty, (vii) competence, (viii) perception of past (last five years) and (ix) expectations for the future (next five years).

The index of attitude is based on six different hypothetical situations where we ask the public how likely they would be to try and use the judiciary to resolve a conflict or problem —the possible answers to those questions are: (i) definitely not, (ii) probably not, (iii) probably yes, (iv) definitely yes. We have developed these hypothetical situations via cognitive interviewing to examine a range of conflicts in which the population of urban centers will often be involved and where they have a choice as to whether to raise proceedings in court, excluding issues where the people involved are not free to decide whether or not to seek a judicial solution. We present cases concerning consumer issues, family, neighborhood, labor and public law. We also tried to create situations in which people from very different income and social groups would all experience and situations in which respondents will be asked to envisage occupying different positions in the conflict —thus, for example, in one circumstance the respondent is the consumer, with a weaker position and in another situation the interviewee is the contractor, in respect of service provision, having a stronger position.

II. The index development

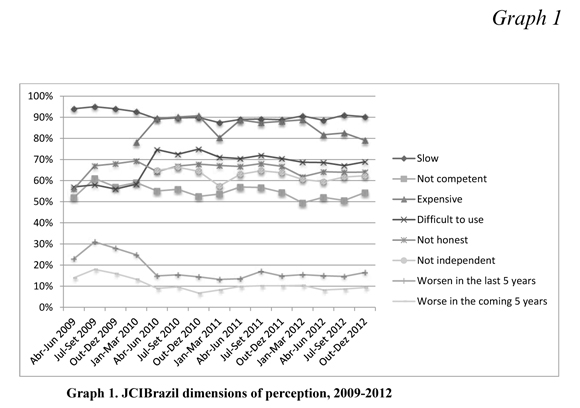

Since April 2009, JCIBrazil has been published quarterly, amounting to twelve waves until December 2012. The index varies from 0 to 10, with 0 meaning no confidence in the judiciary and 10, full confidence in the judiciary.15 The overall results point to a trend of poor assessment of the judiciary as a public service provider. What leads to such a bad evaluation is in first place the slowness in response (around 90% of respondents believe judiciary is time-consuming, resolving conflicts slowly or very slowly). Furthermore, cost to access the courts is high or very high in the view of the majority of the public (around 80%). And in third place, most of the respondents (around 70%) believe the judiciary is difficult or very difficult to use.

Two other problems that drag judicial confidence down are lack of honesty and independence (around 60% see the judiciary as being little or nothing at all honest and little or nothing at all independent).

The only three positive evaluations judiciary gathers are perception of past and expectation for the future —the majority of respondents (around 70%) believe judiciary is better now in all dimensions than it was in the past and expects it to be even better in the near future. Also, in terms of competence (how good is the answer judiciary gives when deciding conflicts), around half of respondents evaluate it as being good or very good.

Results regarding perceptions of the Judiciary clearlypoint to where the efforts and resources should be allocated in order to improve perception of the system: speed and access in the first place. And also indicate that in public perception there are things being made in order to make judiciary more efficient (perception of past and expectation for future) —which means communication of those changes is being successful.

Despite the poor perception of the judiciary, the majority of respondents stated they would seek the judiciary to resolve conflicts. Considering the six hypothetical situations, when it comes to family, labor and consumer matters, around 80% of respondents declared they would definitely go to the courts to solve the problem. And around 70% stated that they would seek judicial remedy in case of a conflict involving neighbors or a medical error.

Results on the attitudinal questions indicate that judiciary is still seen as the best place to seek the realization or protection of a right that has been denied or infringed.

This apparent paradox raises the question of why people would rely on the institution they evaluate so badly to solve their problems? Two hypotheses seem to be appropriate to explain this paradox: first could be the absence or ignorance of o ther effective mechanisms for conflict resolution. Second, could be a reflex of the perception ofjudiciary's improvement, if compared to the past 5 years, as well as the expectation for future enhancement. Since they expect it to improve, if they face conflicts in the future, respondents declare they would seek the judiciary, which they hope, will be better.

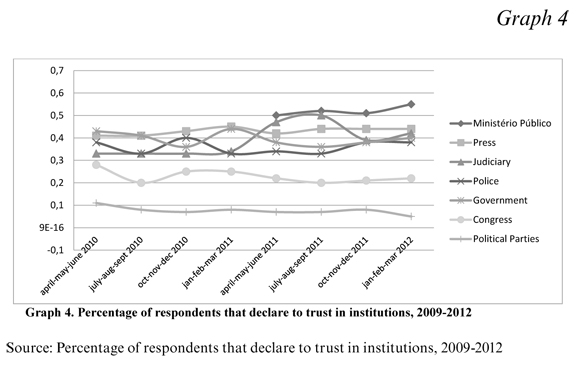

After the first year running the JCIBrazil research, we started to compare public trust in the judiciary with trust in other institutions, in order to understand how confidence in the judiciary varies alongside confidence in institutions like police, political parties, federal government, congress and the press.

We have to consider that most surveys measure confidence or trust with one single question: how much interviewee trusts or have confidence in the institution being investigated, with no specific definition of trust. That's relevant because trust is usually considered as something linked to predictability, that is, to the fact that someone will keep their word (when it comes to trust in people) or that something will function in the way it is designed to function (when it comes to institutions).

Here we can call forth the division proposed by David Easton16 between specific support and diffuse support. Easton defines specific support as a set of attitudes towards an institution based on the perception of fulfiLLMent of the requirements and expectations of its role. And diffuse support refers to a reservoir of favorable attitudes or "good will" towards the institution independent of its performance.

We can assume with the literature that the high level of public confidence in the judiciary is a good indicator of whether the courts are being effective. And as trust and confidence are variable across cultures, we should systematically measure public confidence in the judiciary comparing the results with levels of confidence in other public and government institutions, in order to make sense of the results.

In spontaneous statement about how much people trust the judiciary, only about 30% of respondents answered that judiciary is somewhat reliable or very reliable. However, there were a change in that answer when the order of questions was altered. At first, we began by asking how much people trusted the judiciary; that was the very first question to be asked in interviews. Then we would ask about all the other dimensions in the sub-index of perception and at last we would ask about trust in other institutions. But on the second wave of 2011 (April, May, June), we made an important modification in the order of questions: we began to rotate institutions. It means that we would first ask about the other 8 dimensions of the sub-index of perception and after that we would ask about trust in institutions, contextualizing judiciary among other institutions, and rotating the position of them. That procedural change made a considerable difference: trust in judiciary increased to almost 50%. To make sure if was an effect of order, on the 11th and 12th waves (October, November, December of 2011 and January, February and March of 2012) we went back to the previous order, asking about trust in judiciary initially. The level of confidence dropped, but still remained higher than it used to be until the beginning of 2011. Now trust in judiciary is around 40%, which may imply that something has changed in public perception for better.

Comparing the confidence people have in the judiciary with confidence in other institutions, we see that during the whole series, in the eyes of the population the Judiciary is only more reliable than Congress and Political Parties. Now it started to be more reliable than the police as well, and sharing almost the same level of confidence that federal government and press.

In the second wave of the study (April, May, June of 2010), we started measuring the use of judiciary, by asking respondents whether they or someone living in their household filed a lawsuit in the judiciary. Since then, we have been getting as a result that almost half of the interviewees already had some experience with the judiciary (in person or by someone living in their household). There is a clear trend indicating that income and education are related to access to justice: the higher the income and level of education, the higher the use of judiciary. Issues that most take people to judiciary are labor, consumer and family (almost 90% of interviewees that went to the courts had a problem related to one of those three subjects).

We also begun exploring how people actually behave when they face problems in three common areas of dispute: (i) received unfair bill collection by a company (telephone, bank, or store) and could not solve the problem with the company; (ii) was fired and did not receive what was legitimately owed; and (iii) had a car accident and did not solve the problem with the other part/their insurer. After presenting each situation we asked the respondent: (i) whether he/she had experienced a situation similar to each one of those listed and (ii) having gone through any situation, whether they went to the judiciary or not. Court users are asked why they involved the judiciary and their satisfaction/dissatisfaction with the service they received. Those who experienced a problem but did not seek judicial help were asked the reasons why.

Results over time show that around 20% of interviewees already received unfair billing, 15% had labor issues and 10% were involved in a car accident. Around 60% of the ones involved in any of those issues went to the courts looking for resolution. Considering the 40% that didn't went to court, their most frequent reason raised by them was related to the slowness of answer and high costs associated with the use of judicial system.

Another important item we started to measure in 2010 was the perception and acceptance of alternative resolution methods to solve conflicts. We ask respondents if they eventually get involved in a situation that required judicial remedy, if they would accept instead of a trial, an agreement via alternative dispute resolution mechanisms, adr methods. Only around 40% declare they would — the majority of the respondents say they would prefer going to courts instead.

In 2012 we inaugurate the forth year of the index, and started looking at new dimensions in order to explain what triggers confidence in the judicial system. Hence, we are looking at levels of respect and adherence of respondents to the law (compliance).17

III. The index consolidation

In this paper we also explore some of the impacts of JCIBrazil, considering its presence in media, and reflex in academia, leading to the creation of two new indexes —and consequentially the potential in influencing and subsidizing public policy.

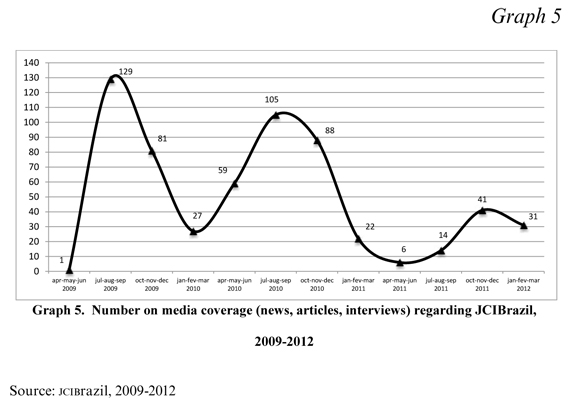

Monitoring the appearance of the index in the media from March 2009 to March 2012 (using as a key word for search the name of the indicator: ICJBrasil), we extracted the degree of visibility and insertion of JCIBrazil in the national media, and realized since its creation it has been subject of increasing popular attention. Considering the press (printed newspapers and weekly news magazines), tv and law specialized sites on internet (ConJur and Migalhas) we found a total of 604 references.

We can see two p eaks in the series: the first one in 2009 (July, June, Augu st), referent to the launch of the indicator. And the second peek occurred in 2010 (July, June, August), regarding changes in the index and inclusion of new m easured dimensions. As a positive effect, every semester the media is interested in disclosing and discussing the results.

The creation of the JCIBrazil led to the creation of new indicators by other institutions working on the evaluation of the Brazilian legal system quality: Social Perception System of Indicators, SIPS, by the Institute of Appli ed Economic Research, IPEA18 and Justice Confidence Index of Lawyers, ICAJ, by the Foundation for Research and Development of Administration, Accountability and Economy, fundace.19

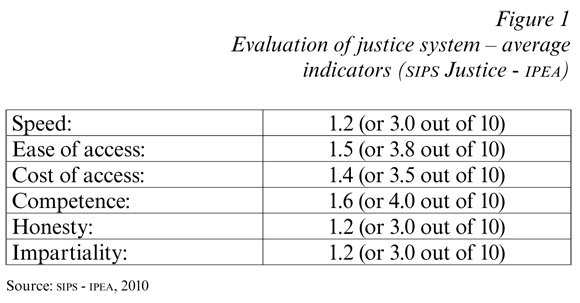

In November 2010, the Institute of Applied Economic Research, IPEA, started to publish an indicator to assess social perception on the judiciary in a study called Social Perception System of Indicators, SIPS.20

The purpose of IPEA indicator is the same as the JCIBrazil, which is to measure public perception on judicial performance. But the methodology both studies employ are somewhat different. First in the scope, while JCIBrazil considers 15 different questions regarding 2 dimensions (perception and attitude), SIPS works with 7 questions on the perception dimension exclusively.

The first question of SIPS examines the overall perception on justice, expressed through a grade they attributed, ranging from 0 to 10 to rate the country's justice system. In the sequence, interviewees evaluate six dimensions of justice: (i) speed in deciding cases; (ii) ease of access; (iii) cost of access; (iv) ability to make good decisions (competence); (v) honesty of the members of justice; and (vi) impartiality of justice, i.e., its ability to treat rich and poor, black and white, men and women, all alike. Respondents say for each of these dimensions: if justice is doing very bad, bad, average, good, or very good.

The IPEA study is also different in terms of methodology and sample. It interviews 2.689 respondents face-to-face, considering all 27 Brazilian States.

The average grade for the justice system obtained was 4.55 (out of 10), and regarding specific dimensions, they all lead to a bad picture of the justice system, being speed, impartiality and honesty the worse ones.

If we were to employ the same methodology used in the JCI-Brazil, summing up the seven dimensions we get an average of 3,5 regarding perception —half point smaller than the measure obtained by our index, but displaying the same trend of poor evaluation.

In May 2011, IPEA released new data from that same research, considering the evaluation of institutions and the behavior of interviewees regarding the access and the habits of Brazilians toward justice. In terms of perception of the judiciary, the institution got 2,1 (out of 4), which indicates that perception on the work judges are doing are not so good.

Regarding the use of judiciary, IPEA asks a different question compared to JCIBrazil - IPEA question respondents about the most serious problem they faced considering a descriptive list of 13 different situations (family, neighborhood, labor relations, people with which did business, companies with which did business, crime and violence; tax or other conflicts with the Secretariat of the Federal Revenue of Brazil,21 social security, welfare or demands for social rights; traffic, property, child and adolescent; violence involving state agents; problems with public offices or enterprises), while JCIBrazil asks whether the respondent or someone living in their household has used the courts or filed any lawsuit or in court, and if positive in which area.

Although there are such differences, both studies show the same trend, namely the poor evaluation of judicial system and low confidence in courts and at the same time an increase in the demand for judicial services as education and income increases.

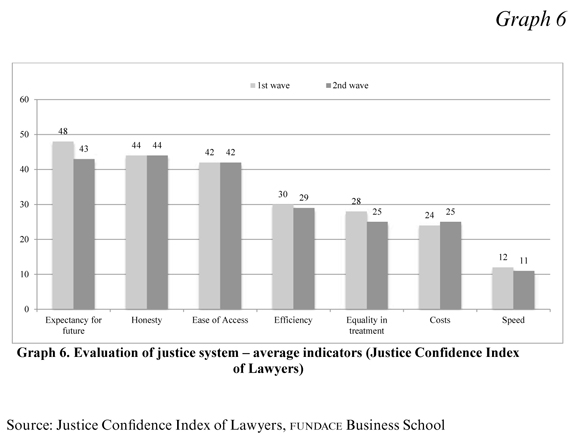

A second study built an indicator of judicial performance from the lawyers' point of view —Justice Confidence Index of Lawyers, run by fundace Business School. The research was developed based on individual questionnaires sent to lawyers via the Internet. Lawyers were located primarily on the website of the Brazilian Bar Association, and in specialized magazines and social networks. The researchers contacted 7 thousand lawyers in the first wave (August-December 2010, getting back 706 respondents), and 15 thousand lawyers in the second wave (January-July 2011, getting back 1.119 respondents).

The Justice Confidence Index of Lawyers is composed of 7 indicators: (i) equality in treatment; (ii) efficiency; (iii) honesty; (iv) speed for the solution of disputes; (v) cost of access; (vi) ease of access and (vii) expectation for next five years (better x worse). The indicator varies from 0 (no confidence) to 100 (full confidence).

In the first wave the index was 32,7 and in the second, 31,2 —which, alongside JCIBrazil and SIPS Justice— IPEA, indicates a very poor evaluation of Brazil's judicial system.

Speed and costs are seen as the worse characteristics of the Brazilian judicial system, same top two aspects most criticized by the general population, as shown by the JCIBrazil. The results of Justice Confidence Index of Lawyers go in the same direction of the ones in JCIBrazil.

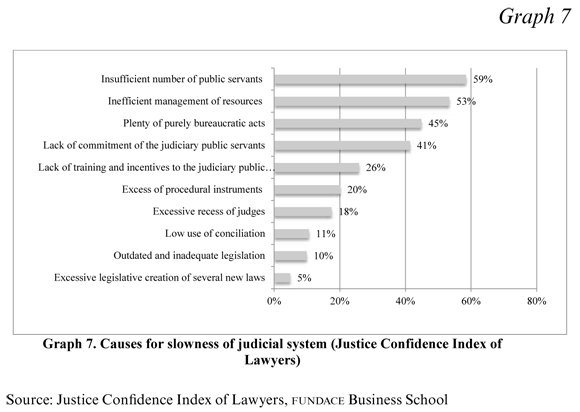

In the second wave of the study, researchers asked lawyers for the causes of the slowness criticized by them. The most cited causes were the insufficient number of public servants and the inefficient management of the resources, especially financial. Excessive bureaucratic acts and lack of commitment of public servants were also significantly mentioned.

From the lawyer's point of view, in order to fight the slow pace ofjustice, public policy should focus primarily on more efficient court administration, associated with the hiring, training and qualification of the servants ofjustice. Also, reform is needed in the procedural instruments —critics of the purely bureaucratic acts and the excessive procedural instruments sum up 65% of mentions.

IV. Potential for collaboration to public policy

As a constant measurement on the perception of the performance and efficiency of the judicial system, JCIBrazil functions both as a data source to support the development of public policies aimed at improving the system, and as a barometer of the impact produced by policies already adopted for this purpose.

It is difficult to measure the direct impact of JCIBrazil in the design of public policies. But since the JCIBrazil is a measure of public opinion perception, we can look at policies being adopted and check if they respond to public perception and also we can point to the problems policymakers should pay closer attention.

Since 2004, with the pass of judicial reform and the implementation of the National Judicial Council, CNJ,22 there was a growing trend pointing to the need of data production in order to inform policies to improve the judicial system.

Brazil doesn't have a strong tradition in the production of judicial statistics. It was only in 1989, just one year after the democratization, the National Data Bank of the Judiciary, BNDPJ,23 was created by the then President of the Supreme Court. This database was intended to gather statistics from all judicial and administrative courts of the country, providing information about the amount ofjudges positions —existing and provided—, oNGOing cases, number of new cases, nature of the cases, etc. In 2006, the BNDPJ was abolished and was installed in its place the Statistical System of the Judiciary, SIESPJ,24 established by CNJ Resolution No. 15/2006. The siespj became the official repository of data from the Brazilian justice system, being responsible for the annual publication of the report Justice in Numbers. The Justice in Numbers had its first edition in 2004. The reports are based on data provided by each of the country's courts, bringing number of cases distributed and judged per year. The report also brings information on the number of judges, court budget, congestion charge and workload of courts.

The CNJ also has a Department of Judicial Research, which goal is to develop research, studies and information systems to improve the judiciary, as well as provide technical and institutional support to the actions of CNJ.

The first acknowledgment of the JCIBrazil's potential impact for the better understanding and support for public policies on the judicial system was the prize CNJ gave to the research in 2010: the National Award for Judicial Statistics. The award was designed with the aim of encouraging the production of statistical data that can measure the performance and productivity of the organs of the judiciary in order to contribute to the planning and strategic management of the courts and to the greater effectiveness and transparency of the Brazilian Justice.

CNJ is also responsible for setting what is called "judicial goals".25 The goals are set annually since 2009, as policies designed for monitoring the performance of the judiciary. The most known goal was designed to fight slowness (Meta 2 - goal number 2), determining that all courts identify and decide lawsuits (cases) distributed to judges prior to 2006 within that year. Since 2009, each year the National Judicial Council determines goals judiciary must fulfill —most of them designed to fight workload of cases.

Most of those goals are designed to fight aspects pointed as critical by the three indexes mentioned here: slowness and access (cost and easiness). And we could argue that the perception of the improvement on the judicial system is greatly due to the changes being implemented since 2006 —most of Brazilians believe judiciary is better off now than it was in the past (5 years behind). And they believe it will improve even more in the future. This means people believe and perceive things are being done for its improvement.

But more attention should be given to aspects besides workload of cases —judiciary is not performing well in other important dimensions, such as independency, honesty, competence and fairness. Policymakers need to pay closer attention to what data has been showing for the past three years, there are some trends that can be used to better inform public policies being designed by CNJ.

One specific example is the resolution n. 125, released by CNJ in November 2010, aimed at organizing and standardizing the services of conciliation, mediation and other consensual methods of conflict resolution. The resolution pays attention only to the needs of internal organization and training of judges and public servants, but ignores the resistance that the society still has on that method of conflict resolution —JCIBrazil is measuring perception on alternative dispute resolution methods since 2010. This documented resistance should have been considered in the resolution, incorporating methods to overcome it and have a more efficient program of conflict resolution.

Brazil has been advancing in the production of judicial statistics, but policymakers should rely more closely on those statistics in order to align public policies to the improvement of the system. Attention must be given not only to the production of studies, research and data on the justice system, but also to the use and application of studies results and data.

Pie de página

1Guillermo O'Donnell, Poliarquías e a (in) efetividade da lei na América Latina, 51 Revista Novos Estudos, 37-61 (1998). Available at: http://www.plataformademocratica.org/Publicacoes/19885_Cached.pdf

2Kevin E. Davis, Benedict Kingsbury & Sally E. Merry, Indicators as a Technology of Global Governance, 46 Law and Society Review, 1, 71-104 (2012). Available at: http://www.NYUdri.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/indicatorsasatechnologyofglobalgovernance.pdf

3Justice Studies Center of the Americas (Centro de Estudos da Justica das Américas, ceja) is an agency of the Inter-American System, established in 1999, headquartered in Santiago, Chile. Members of ceja are active members of the Organization of American States, oas. For more information, check http://www.cejamericas.org

4It is important to stress that when it comes to Brazilian judiciary, these datum are produced by the Statistical System of Judiciary (Sistema de Estatística do Poder Judiciário, siespj, previously Banco Nacional de Dados do Poder Judiciário), since 1989. As the official repository of data on Brazilian Judiciary, it publishes since 2004 the report Justice in Numbers (Justiga em Números). For more information, see http://www.CNJ.jus.br/programas-de-a-a-z/sistemas/sistema-de-estatistica-do-poder-judiciario-siespj

5International Consortium for Court Excellence, ICCE, International Framework for Court Excellence, 1 (2013). Available at: http://www.courtexcellence.com/resources/the-framework.aspx. According to the document (6-11), the seven areas are: 1. Court Leadership and Management. 2. Court Planning and Policies. 3. Court resources (human, material and financial). 4. Court Proceedings and Processes. 5. Client Needs and Satisfaction. 6. Affordable and Accessible Court Services. 7. Public Trust and Confidence.

6Joseph L. Staats, Shaun Bowler & Jonathan T. Hiskey, Measuring Judicial Performance in Latin America, 47 Latin American Politics & Society, 4, 77-106 (2005).

7Joseph L. Staats, Shaun Bowler & Jonathan T. Hiskey, Measuring Judicial Performance in Latin America, 47 Latin American Politics & Society, 4, 77-106, 79 (2005).

8The minimum number of interviewees per country was 5 (case of Brazil and Guatemala, whereas they originally sent 56 questionnaires in Brazil and 31 in Guatemala), and the maximum was 13 (case of Argentina, where they originally sent 133 questionnaires). The best return rate they achieved was in Peru, where 11 were returned out of the 21 sent. They justify the preference for expert survey instead of population survey, based on the fact that "respondents' lack of experience and objectivity with respect to the workings of a country's judicial system." Joseph L. Staats, Shaun Bowler & Jonathan T. Hiskey, Measuring Judicial Performance in Latin America, 47 Latin American Politics & Society, 4, 77-106, 84 (2005).

9Maria Tereza Sadek, Judiciârio: mudanças e reformas, 18 Revista Estudos Avançados, 51, 79-101 (2004). Available at: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ea/v18n51/a05v1851.pdf. Joseph L. Staats, Shaun Bowler & Jonathan T. Hiskey, Measuring Judicial Performance in Latin America, 47 Latin American Politics & Society, 4, 77-106 (2005). United Nations, Civil and Political Rights (New York, United Nations, 2005).

10United Nations General Assembly, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (New York, United Nations, 1966).

11Data from Conselho Nacional de Justica, CNJ, CNJ Reports, Justiga em Números. Available at www.CNJ.jus.br, http://www.CNJ.jus.br/programas-de-a-a-z/eficiencia-modernizacao-e-transparencia/pj-justica-em-numeros

12Anthony Giddens, Modernity and Self-Identity. Self and Society in the Late Modern Age (Polity, Cambridge, 1991). Robert D. Putnam, Comunidade e Democracia: a experiencia da Italia moderna (Fundação Getulio Vargas Editora, FGV Editora, Rio de Janeiro, 2002).

13Gregory A. Caldeira & James L. Gibson, The Legitimacy of the Court of Justice in the European Union: Models of Institutional Support, 89 American Political Science Review, 2, 356-376 (1995). Available at: http://jameslgibson.wustl.edu/apsr1995.pdf. Joseph L. Staats, Shaun Bowler & Jonathan T. Hiskey, Measuring Judicial Performance in Latin America, 47 Latin American Politics & Society, 4, 77-106 (2005). Sara C. Benesh, Understanding Public Confidence in American Courts, 68 Journal of Politics, 3, 697-707 (2006).

14Ryan Salzman & Adam Ramsey, Judging the Judiciary: Understanding Public Confidence in Latin American Courts, 55 Latin American Politics and Society, 1, 73-95 (2013).

15Respondents are part of Brazil's general population (from 18 to 75 years old), considering seven Brazilian States (which account for 60% of the country population). Sample size is 1.550 respondents in each wave (every three months). Interviewees are select by income, education, age and gender (to represent Brazilian population according to official statistics), and accessed by telephone (landline and mobile). For details on the sample and calculation of jcmrazil, see Luciana Gross Cunha & Fabiana Luci de Oliveira, The Justice Confidence Index in Brazil: Why, How and for Whom it Has Been Produced, in Law and Society Association - Annual Meeting, 2011, vol. 1, 62 (Law and Society Association, lsa, San Francisco, 2011).

16 David Easton, A Re-assessment of the Concept of Political Support, 5 British Journal of Political Science, 4, 435-557 (1975).

17We based some of the questions on Tom R. Tyler, Why People Obey the Law (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2006).

18Sistema de Indicadores de Percepção Social by the Instituto de Pesquisa Económica Aplicada.

19Índice de Confianca dos Advogados na Justica by the Fundacáo para Pesquisa e Desenvolvimiento da Administracáo, Contabilidade e Economia.

20Institute of Applied Economic Research, ipea, Social Perception System of Indicators, SIPS, Sistema de Indicadores de Percepçâo Social, Justiça (2010, 2011).

21 Secretaria da Receita Federal do Brasil: http://www.receita.fazenda.gov.br/

22Conselho Nacional de Justiça.

23Banco Nacional de Dados do Judiciário.

24Sistema de Estatística do Poder Judiciário.

25Metas.

Bibliography

Books

Giddens, Anthony, Modernity and Self-Identity. Self and Society in the Late Modern Age (Polity, Cambridge, 1991). [ Links ]

Putnam, Robert D., Comunidade e Democracia: a experiencia da Itália moderna (Fundação Getulio Vargas Editora, FGV Editora, Rio de Janeiro, 2002). [ Links ]

Tyler, Tom R., Why People Obey the Law (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2006). [ Links ]

United Nations General Assembly, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (New York, United Nations, 1966). [ Links ]

Journals

Benesh, Sara C., Understanding Public Confidence in American Courts, 68 Journal of Politics, 3, 697-707 (2006). [ Links ]

Caldeira, Gregory A. & Gibson, James L., The Legitimacy of the Court of Justice in the European Union: Models of Institutional Support, 89 American Political Science Review, 2, 356-376 (1995). Available at: http://jameslgibson.wustl.edu/apsr1995.pdf [ Links ]

Davis, Kevin E.; Kingsbury, Benedict & Merry, Sally E., Indicators as a Technology of Global Governance, 46 Law and Society Review, 1, 71-104 (2012). Available at: http://www.NYUdri.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/indicatorsasatechnologyofglobalgovernance.pdf [ Links ]

Easton, David, A Re-assessment of the Concept of Political Support, 5 British Journal of Political Science, 4, 435-557 (1975). [ Links ]

O'Donnell, Guillermo, Poliarquias e a (in) efetividade da lei na América Latina, 51 Revista Novos Estudos, 37-61 (1998). Available at: http://www.plataformademocratica.org/Publicacoes/19885_Cached.pdf [ Links ]

Sadek, Maria Tereza, Judiciário: mudancas e reformas, 18 Revista Estudos Avancados, 51, 79-101 (2004). Available at: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ea/v18n51/a05v1851.pdf [ Links ]

Salzman, Ryan & Ramsey, Adam, Judging the Judiciary: Understanding Public Confidence in Latin American Courts, 55 Latin American Politics and Society, 1, 73-95 (2013). [ Links ]

Staats, Joseph L.; Bowler, Shaun & Hiskey, Jonathan T., Measuring Judicial Performance in Latin America, 47 Latin American Politics & Society, 4, 77-106 (2005). [ Links ]

Brazilian normativity

Conselho Nacional de Justifa, CNJ, Resolução n. 125/2010, dispöe sobre a Política Judiciária Nacional de tratamento adequado dos conflitos de interesses no ámbito do Poder Judiciário e dá outrasprovidencias. Available at: http://www.CNJ.jus.br///images/atos_normativos/resolucao/resolucao_125_29112010_16092014165812.pdf [ Links ]

Conferences

Cunha, Luciana Gross & Oliveira, Fabiana Luci de, The Justice Confidence Index in Brazil: Why, How and for Whom it Has Been Produced, in Law and Society Association - Annual Meeting, 2011, vol. 1, 62 (Law and Society Association, lsa, San Francisco, 2011). [ Links ]

Index

Conselho Nacional de Justifa, CNJ, CNJ Reports, Justica em Números. Available at: www.CNJ.jus.br, http://www.CNJ.jus.br/programas-de-a-a-z/eficiencia-modernizacao-e-transparencia/pj-justica-em-numeros [ Links ]

Fundação para Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento da Administração, Contabilidade e Economia, ftjndace, Justice Confidence Index of Lawyers. Available at: http://www.fundace.org.br/ [ Links ]

Institute of Applied Economic Research, IPEA, Social Perception System of Indicators SIPS, Sistema de Indicadores de Percepção Social, Justica (2010, 2011). [ Links ]

International Consortium for Court Excellence, ICCE, International Framework for Court Excellence (2013). Available at: http://www.courtexcellence.com/resources/the-framework.aspx [ Links ]

Justice Studies Center of the Americas, ceja, Índice de accesibilidad a la información judicial en internet, iacc (2012). Available at: http://www.cejamericas.org/ [ Links ]

Websites

Conselho Nacional de Justifa, CNJ, www.CNJ.jus.br Consultor Jurídico, ConJur, http://www.conjur.com.br/Migalhas, http://www.migalhas.com.br/ [ Links ]

Secretariat of the Federal Revenue of Brazil, Secretaria da Receita Federal do Brasil: http://www.receita.fazenda.gov.br/ [ Links ]