Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Revista Criminalidad

versão impressa ISSN 1794-3108

Rev. Crim. vol.60 no.3 Bogotá out./dez. 2018

Criminological studies

Implications of the integration process of the administrative records of criminality between the SPOA (Oral Accusatory Criminal System) of the Attorney General's Office (FGN) and the SIEDCO (Statistical, Delinquency, Offenses and Operations Information System) of the National Police of Colombia (PONAL), and the implementation of the "¡ADenunciar!" app on crime figures

1Magíster (c) en Pensamiento Estratégico y Prospectiva. Jefe, Equipo de Análisis Criminológico, Observatorio del Delito, Dirección de Investigación Criminal e INTERPOL. Bogotá, D.C., Colombia jair.rodriguez1243@correo.policia.gov.co

2PhD en Economía. Director de Políticas y Estrategia, Fiscalía General de la Nación. Bogotá, D.C., Colombia daniel.mejia@fiscalia.gov.co

3Magíster en Economía y en Administración Pública en Desarrollo Internacional. Jefe de Análisis de Información y Estudios Estratégicos, Secretaría de Seguridad, Convivencia y Justicia de Bogotá Alcaldía Mayor de Bogotá Bogotá, D.C., Colombia lorena.caro@scj.gov.co

4Magíster en Criminología y Victimología. Analista, Grupo Observatorio del Delito, Dirección de Investigación Criminal e INTERPOL. Bogotá, D.C., Colombia mauricio.romero1476@correo.policia.gov.co

5Especialista en Gerencia de Proyectos. Coordinador, Grupo de Análisis Criminal. Delegado para la Seguridad Ciudadana, Fiscalía General de la Nación. Bogotá, D.C., Colombia frcampos@fiscalia.gov.co

In 2017, the Information System ;SIEDCO; of the National Police ;PONAL;, one of the main sources of criminality information in the country, experienced two important changes in the consolidation of its crime figures. The first, was the integration into SIEDCO of the administrative records of complaints of the Attorney General’s Office ;FGN; Criminal System ;SPOA;. The latter was the implementation of the "¡ADenunciar!" (“ReportACrime!”) app, an application that allows citizens to file some complaints through the FGN’s Internet webpage. These changes have generated important variations in the series of data that measure the criminality registered in the country, which prevent the comparability of crime figures in recent years in the country.

The objective of this document is to explain how the integration and aggregation of criminality information was carried out, and what was its effect on the collation of statistical figures over time. The methodology used in this document is descriptive with a quantitative approach, performing a statistical analysis of the consolidated figures in the SIEDCO information system and other complementary sources of information that allow for characterizing the integration and aggregation of information. The results of the analysis show that the increase registered in the figures of criminality is the product of the information integration and not necessarily increases in criminality. Likewise, this advance in the integration and aggregation of crime information was the result of the interinstitutional synergy between the National Police and the Attorney General’s Office, which allowed the consolidation of information and the provisioning of a mechanism to facilitate citizens reporting crime.

Key words: Criminal statistics; criminality measurement; criminal information; crimes; real crime; hidden crime

En el 2017, el Sistema de Información Estadístico, Delincuencial, Contravencional y Operativo ;SIEDCO; de la Policía Nacional ;PONAL;, una de las principales fuentes de información de criminalidad del país, experimentó dos cambios importantes en la consolidación de sus cifras de criminalidad. El primero fue la integración al SIEDCO de los registros administrativos de denuncias del Sistema Penal Oral Acusatorio ;SPOA; de la Fiscalía General de la Nación ;FGN;. El segundo fue la implementación de “¡ADenunciar!”, un aplicativo que permite a los ciudadanos interponer algunas denuncias a través de internet. Estos cambios han generado variaciones importantes en las series de datos que miden la criminalidad registrada en el país, las cuales impiden la comparabilidad de las cifras de criminalidad en los últimos años en el país.

El objetivo de este documento es explicar cómo se llevó a cabo la integración y agregación de información de criminalidad, y cuál fue su efecto en el cotejo de cifras estadísticas a través del tiempo. El método utilizado en este documento es descriptivo con un enfoque cuantitativo, realizando un análisis estadístico de las cifras consolidadas del SIEDCO y otras fuentes de información complementarias que permiten caracterizar la integración y agregación de información. Los resultados del análisis muestran que el incremento registrado en las cifras de criminalidad es producto de la integración de información y no necesariamente de aumentos en la criminalidad. Asimismo, este avance en la integración y agregación de información de criminalidad fue el resultado de la sinergia interinstitucional entre la Policía Nacional y la Fiscalía General de la Nación, que permitió la unificación de información y la provisión de un mecanismo facilitador de la denuncia ciudadana.

Palabras clave: Estadísticas criminales; medición de la criminalidad; delitos; criminalidad real; criminalidad oculta

No ano 2017, o Sistema de Informação Estatístico, Delinquencial, Contravencional e Operativo ;SIEDCO; da Policia Nacional ;PONAL;, uma das principais fontes de informação da criminalidade do país, teve duas mudanças importantes na consolidação de suas cifras de criminalidade. A primeira foi a integração ao SIEDCO dos registros administrativos de denúncias do Sistema Penal Oral Acusatório ;SPOA; da Fiscalia Geral da Nação ;FGN;. A segunda foi a implementação de “¡ADenunciar!”, um aplicativo que permite aos cidadãos interpor algumas denúncias por meio da internet. Essas mudanças têm gerado variações importantes nas séries de dados que medem a criminalidade registrada no país, as quais impedem a comparabilidade das cifras de criminalidade nos últimos anos no país.

O objetivo deste documento é explicar como se desenvolveu a integração e a agregação de informação da criminalidade, e qual foi seu efeito no cotejo de cifras estatísticas ao longo do tempo. O método utilizado neste documento é descritivo com uma abordagem quantitativa, realizando uma análise estatística das cifras consolidadas do SIEDCO e outras fontes de informação complementarias que possibilitam caracterizar a integração e agregação da informação. Os resultados da análise mostram que o incremento registrado nas cifras de criminalidade é produto da integração de informação e não necessariamente de aumentos na criminalidade. Assim mesmo, este avanço na integração e agregação da informação da criminalidade foi o resultado da sinergia interinstitucional entre a Policia Nacional e a Fiscalia Geral da Nação, que permitiu a unificação da informação e a provisão de um mecanismo facilitador para a denúncia cidadã.

Palavras chave: Estatísticas criminais; medição da criminalidade; delitos; criminalidade real; criminalidade oculta (fonte: Tesauro de política criminal latino-americana - ILANUD)

1. Introduction

The design and implementation of evidence-based public policies depend directly on the quality and quantity of information available. In this sense, the Colombian State has been improving through the optimization of information systems related with criminality and citizen security, developing a greater capacity for collecting, integrating and systematizing data (Ministry of Justice and Law, PONAL, INMLCF (National Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences) & FGN, 2017, National Planning Department ;DNP;, 2014, Ministry of Justice and Law, Colombia’s Presidential Agency for International Cooperation & European Union, 2012). This situation is aligned with international standards, such as those of the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations ;UN; (2009), which, through Resolution 2009/25, urged the member States to increase their efforts to improve information gathering tools - such as technological platforms and the criteria for data recording -, oriented towards obtaining objective, scientific and internationally comparable assessments of new criminal trends (Norza, Peñalosa & Rodríguez, 2017).

In this regard, during the year 2017 the Nation Attorney General's Office (FGN) and the National Police (PONAL) implemented two important actions, aimed at improving the measurement of the country's crime figures and facilitating the reporting channels. The first consisted in integrating information from the Oral Accusatory Criminal System (SPOA) of the FGN with the information from the Statistical, Delinquency, Offenses and Operations Information System (SIEDCO) of the PONAL, having as its main objective to consolidate the country's criminality figures. The second was to implement a complaint reporting application through the internet, called “¡ADenunciar!”, which allows for citizens to inform the authorities of certain criminal acts through the use of Information and Communications Technologies (ICT), and bring justice closer to the citizen.

This article aims to describe the two actions described above, as well as to point out the consequences that these two changes have had on the comparability of crime figures in recent years. The latter is of relevant importance, because although the aforementioned actions improved the quality of the information and decreased the underreporting, they also had implications for the analysis and interpretation of the behavior over time of some crime figures in the country. In order to show that the change in the registered crime figures is explained above all by the two mentioned methodological modifications and not necessarily with an increase in real crime, this article presents some analyzes carried out with alternative criminality data sources that were not affected by the integration of the information systems or by the implementation of the “¡ADenunciar!” application. These analyzes show that the increases observed in the registered crime figures, after the two methodological changes, are not reflected in the crime figures coming from other alternative sources.

The rest of the article is organized as follows: the first section corresponds to the introduction. The second one describes in a general way the background that gave rise to the integration of the information. The third section describes the characteristics of the SIEDCO and SPOA information systems. The fourth section gives an account of the information integration process of both systems. The fifth section explains the implementation of the virtual “¡ADenunciar!” complaint report application. The sixth section clarifies the implications of the integration and aggregation of the information on criminality indicators and, finally, the seventh section presents the conclusions of the analyzes carried out.

2. Background

The integration of the SIEDCO and SPOA information systems, as well as the implementation of the “¡ADenunciar!” application, are framed within the Institutional Strategic Plan of the National Police and the Nation Attorney General’s Office. This plan has been constituted as a significant advance for the implementation of collection, processing, analysis and dissemination processes of statistical information coming from different the agencies, which contribute to making public policy decisions based on evidence and which serve as a basis for designing and updating basic management indicators systems.

The integration of the figures coming from the PONAL and the FGN began to be carried out in 2017, and retroactively covered the crime figures for 2016. The integration took as reference the International Classification of Crimes for Statistical Purposes ;ICCS;, which it is based on classifying offenses into internationally agreed concepts, definitions and principles, with the purpose of improving the analysis, coherence and the national and international comparability of statistics (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime ;UNODC;, 2015).

At the same time, with the process of integrating the aforementioned systems, the coverage of the information capture points was also broadened and interinstitutional agreements of a binding nature were generated between the PONAL and the FGN. In addition, the complaints reporting system was strengthened through the creation of the virtual “¡ADenunciar!” complaint reporting application, a channel that began operations on July 26, 2017. This new application allows the filing of complaints in a virtual manner, through a web page or an application for smartphones, of certain type of thefts (to commerce, to people and households), information technology crimes, material with explicit content of sexual exploitation to children and cases of extortion.

Due to the aforementioned changes, the need to work on the processing of information was raised during the process, in such a way that it was possible to develop management capacities for the decision making, within a framework of interoperability of the information systems of the Justice System entities (DNP, 2014). As a result of this, the technical desk for the Unification of Statistical Figures was created, which was framed within the National Police Institutional Strategic Plan and the Nation Attorney General’s Office.

This process, carried out by the two institutions, affected the comparability of the crime figures for the years 2016, 2017 and 2018, as it generated methodological changes in two dimensions. First, starting in 2016 and progressively in 2017 and 2018, the SIEDCO database began to receive cases coming from the FGN’s SPOA system that were not previously registered; and second, with the implementation of the “¡ADenunciar!” application, it was made easier for citizens to file complaints, with which significantly increased the number of crimes reported to the authorities. The two changes are significant, since they bring closer the figures of crime registered to real crime, but it is necessary to clarify that these methodological changes affected the comparability of the registered crime figures over time (years 2016, 2017 and 2018).

a. What are real crime and registered crime?

To provide a conceptualization on the way to understanding the behavior of statistical crime records, an existing classification considers three types of crime: the real, the registered and the hidden, under which all the countries worldwide, in the last decade, have promoted actions to advance in the knowledge of real crime, and thus reduce the gap between real and registered crime. In fact, it is described below how the Colombian Police and the Attorney General's Office have worked within this guideline, which allows for a greater knowledge of crime.

Real criminality makes reference to the totality of phenomena related to crime; that is, it is the sum of all the crimes that occurred in a society and within a specific time, regardless of whether they were reported to the competent authorities or not. Given the impossibility of knowing the real crime in its entirety, the categories known as registered crime and hidden crime have been developed (Restrepo, 2008, Redondo & Garrido, 2013).

Registered crime is that part of real crime that is reflected in the records or reports of the authorities, and it is what allows an approximation to real crime. Registered crime has its origin in the decision of a victim or a witness to report a crime, for which they should feel that the grievance has sufficient importance (Center of Excellence for Government, Victimization, Public Safety and Justice Statistical Information ;Cdeunodc;, 2015).

Hidden crime refers to that part of real crime that it is not reflected in official records, either because it is not known by the authorities or because, although being known, it is not recorded in the official or administrative records (Restrepo, 2008; Redondo & Garrido, 2013).

In this regard, an instrument that allows to reduce the gap between registered and hidden crime are the victimization surveys, taking into account that from the information obtained by these surveys, the proportion of crimes that are not recorded in the official statistics can be calculated.

The victimization surveys are usually conducted in conjunction with the perception of security. Both types of surveys are conducted in Colombia in cities such as Bogotá, Barranquilla and Medellín, and these, in addition to complementing the official criminality figures thanks to questions about different types of victimization, offer information about the perceptions of citizens regarding aspects such as the security of their environments and management of the organizations responsible for citizen security (Chamber of Commerce of Bogotá, 2018, Barranquilla how we are doing, 2018, Medellin how we are doing, 2018, amongst others).

3. The two main sources of crime information in the country

The following describes the characteristics of the two information systems involved in the process of integrating the information on criminality in the country, which began in 2017: The Oral Accusatory Criminal System (SPOA) of the Attorney General’s Office of the Nation and the Statistical, Delinquency, Offenses and Operations Information System (SIEDCO) of the National Police.

a. The Oral Accusatory Criminal System (SPOA)

This system is managed by the FGN, and was created in response to the need to systematize the information of complaints and judicial operations activities collected in compliance with the main function of the Attorney General’s Office, which is "to carry out the exercise of the criminal law-enforcement action and conduct the investigation of the facts that have the characteristics of a crime that comes to their knowledge through the complaint report, special summons, accusation or ex officio, provided there are enough reasons and factual circumstances that indicate the possible existence of it " (Constitution of Colombia,1991).

The system was created under Law 906 of 2004, and began to be implemented starting in the year 2005. The SPOA is one of the information systems that receives reports of crimes that have occurred in Colombian territory. The sources of the complaints that feed the system are: the User Assistance Centers ;SAU;, the Immediate Reaction Units ;URI;, the Early Intervention Program, the Local Units, the Technical Investigation Body ;CTI;, the Support Structures ;EDA;, the Center for Comprehensive Attention to Victims of Sexual Violence ;CAIVAS;, the Center for Comprehensive Criminal Assistance to Victims ;CAPIV; and the allocated offices that receive complaints submitted in writing by citizens. Other entities, such as the National Penitentiary and Imprisonment Institute ;INPEC; and the Family Courts, are also sources of complaint to the SPOA.

The SPOA is also fed with the information contained in the SIEDCO since the year 2005, which gathers information through the SIDENCO1, a module that the different complaint reception centers of the PONAL have. The SPOA was designed for judicial purposes, which is why the variables contemplated in it are designed to facilitate the criminalization of the offenses, to record the proceedings under the investigation proceedings and to follow up on criminal investigations within the framework of the justice process that the FGN carries out. Currently, the system is being fitted with the incorporation of variables such as victim, victimizer, property, characterization, modalities, motives, weapons, sites of the event, amongst others. This is being done in conjunction with the PONAL for crimes such as theft, homicide, kidnapping, extortion, information technology crimes and assault and battery charges2.

b. The Statistical, Delinquency, Offenses and Operations Information System (SIEDCO)

i. Background

Since 1958, the National Police initiated the orderly collection of administrative records on criminal behavior and police services3. Initially, the collection process was carried out manually by each one of the country's police units. The collected figures were then collated, analyzed and reported each month by a company hired by the National Police (PONAL, 2015).

Initially, the National Police consolidated the information related to the crimes established in the Criminal Code, the contraventions of the National Police Code, the cases of suicide, natural disasters and the census of prostitution. Likewise, it registered all the operations activity that the institution carried out. On the other hand, it was not possible to disaggregate the information, according to the variables that currently exist, and it was difficult to store historical information (PONAL, 2015).

In the year 2000, the InterAmerican Development Bank ;IDB; allocated approximately US $ 1,000,000 for the National Police to strengthen the statistical operation. In the year 2002, SIEDCO was launched in Bogotá, as a pilot city. In the same way, the Business Objects tool was implemented in order to process, analyze and extract the consolidated information. In 2003, SIEDCO was placed into operation throughout the country (PONAL, 2015).

In the year 2010, the criminality information system of the National Police initiated a process of reengineering, which allowed for the development of the forms in a web environment, so that greater coverage was obtained and online registration of the decentralized units was allowed. In addition, a geographic viewer was installed for the exact spatial location of crimes and behaviors in the country.

Additionally, in the year 2014, the statistical operation of criminality and operational activity known as "Police Conduct and Services"4 was certified before the National Statistics Administration Agency (DANE), the official governing and regulating entity of statistics in Colombia. This certification was given under the rigorous evaluation of an independent expert team from the DANE, which reviewed the thematic, statistical and processes part, so that consistency, comparability and timeliness in the statistical operation was evidenced with respect to its functional structure, its controls in the field and the analysis and dissemination of data.

During the year 2015, the business intelligence tool called SIEDCO Plus was adapted to the police information system, which allows to better visualize the consolidated variables of time, place and mode, as well as to associate the records included in the fields of the system.

The SIEDCO has been a determining factor during the last decade of Colombian events, because it has allowed for the registry of criminal behavior and police actions that have facilitated to the State the design and implementation of public policies on matters of criminality, coexistence and citizen security.

ii. The process of recording information

With the enactment of Law 906 of 2004, Code of Criminal Procedure, it became necessary to implement the module called SIDENCO, which objective was to allow the PONAL to receive citizen complaints, to subsequently bring them to the attention of the competent judicial authority. The complaints registered in the SIDENCO are loaded immediately to the SPOA, with the purpose of assigning and initiating the investigative process at the FGN.

The criminal acts known by the police are taken care of and assigned to the surveillance patrol that knows about the case. This patrol in turn, through written or verbal communications, is responsible for reporting to the Automatic Dispatch Center the data on the case known and its development. The data is recorded in police information bulletins, which are collected and registered daily in the SIEDCO, by the GICRI5 officials belonging to the 51 police units that currently exist (Buitrago, Rodríguez & Bernal, 2015).

The SIEDCO registers information related to the characteristics of the victims, the perpetrators and the crimes themselves, in such a way that the registry is organized around the following levels (UNODC, 2015):

Record of the facts. The SIEDCO records information on time, mode and place, such as the date and time of the event, political department, municipality, area (urban or rural), address, particular conduct ;modus operandi;, type of site, basic police unit where the incident occurred, basic police unit that was notified of it, source and means of jurisdiction that support and backup the administrative record in the database (Buitrago, Rodríguez & Bernal, 2015). Since year 2014, the SIEDCO incorporates a geographic viewer that allows to automatically georeferencing criminal events through their location on a map. This generates information about the geographical coordinates (longitude and latitude) of the place where the recorded event occurred (Buitrago, Rodríguez & Bernal, 2015).

Record of behaviors. When a crime is registered, the infringed behavior classified in the Colombian Criminal Code can be indicated; in the same way, the modality in which the perpetrator executed the crime, the type of weapon used and the means of transport of the aggressor and the victim (Buitrago, Rodríguez & Bernal, 2015).

Record of interveners. The SIEDCO allows to record biographical data of the people who may be involved in a case, both as complainants as well as witnesses, victims, offenders or suspects. In addition, the system allows associating different behaviors to each one of the participants.

Record of assets. The system registers different personal and real property elements associated with a case, with the appropriate detail for each one of them, indicating the type and kind of asset, the quantity, the value, the unit of measurement and their identification data (brand, line, model, color, amongst others). This registry is important, because it allows quantifying the value of the assets involved in the commission of a crime or those belonging to the offended or complainants.

4. The process of integrating information between SIEDCO and the SPOA

The articulation of efforts between the PONAL and the FGN to consolidate the country's crime figures began in early 2017, with the creation of the work desk No. 11, called "Unification of statistical figures". This had the purpose of establishing the methodology for the process of integrating the criminal information consolidated by the two agencies.

For the development of the work desk a work plan was established, focused on four strategic initiatives, which allowed for the articulation, standardization, normalization, consolidation and disclosure of crime figures between both agencies. The initiatives were the following:

Initiative 1. Unification of concepts for the registry of criminal notifications and administrative records. This initiative focused on the standardization and normalization of criteria for the crimes of homicide, robbery (12 characterizations), kidnapping and extortion. This resulted in the construction and validation of three methodological guidelines for the unification of concepts related to the aforementioned crimes.

Initiative 2. Articulation of the SPOA-SIEDCO information systems. This initiative consisted in the articulation of both agencies’ information systems, and allowed for adjusting, creating and homogenizing characterization variables (type of theft), modality, time, mode and place in both systems, which allowed the implementation of a Web Service between the two agencies for the reception of complaints from SIEDCO to the SPOA, and vice versa.

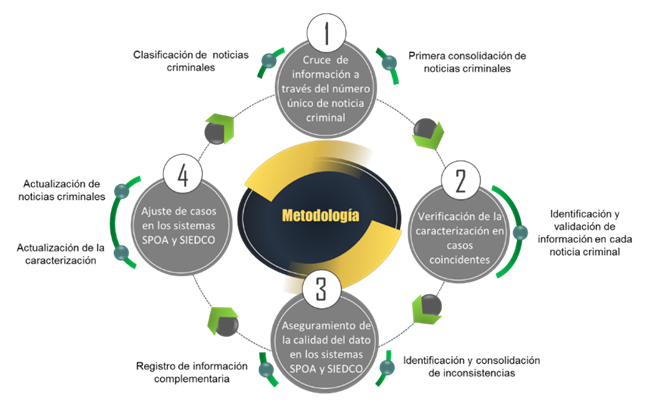

Initiative 3. Consolidation of criminal notifications. This initiative is the backbone of the information integration process, which was carried out through four fundamental steps that operate in a cyclical way (see illustration 1):

Crossing of information through the unique number of criminal notification. Every day there is a crossing made of the criminal notifications contained in both information systems. This allows for the classification of notifications according to their characterization of the crimes and the account of the events. This step initiates the first consolidation of criminal reports/notifications.

Verification of the characterization. After consolidating the criminal notifications, the account of the events is verified with the classification of the conduct. This step allows to identify and validate the information (facts, characterization, interveners and assets) that each criminal notification contains with respect to that established by the Deputy District Attorney of the case.

Assurance of data quality. In this step, the data described in the account of the facts are added to the information systems of both agencies, and which are necessary to obtain an optimum record in the systems. Finally, the inconsistencies that cannot be updated are verified and consolidated. This step is in charge of the Deputy District Attorney of the case.

Case adjustments in both information systems. Finally, the update of the criminal notifications that present information discrepancy in both the SPOA and SIEDCO is made, and the characterization of the theft is updated for the cases that are necessary.

Initiative 3 allowed for the integration of the SPOA and SIEDCO systems, as well as the consolidation of criminal notifications of the crimes of homicide and theft. For this, it was necessary to employ 60 policemen full time, who reviewed and interpreted each one of the criminal notifications of the aforementioned crimes, contained in the SPOA (show figure 1).

Source: National Police (2018). Internal elaboration.

Figure 1 Methodology of aggregation of criminal information

In the case of theft6, for example, between 2017 and up to January 25, 20187, a total of 146,757 criminal notifications were found, of which 27,644 were in both the SIEDCO and the SPOA systems, and 119,113 had different characterizations8 in each one of the systems.

iv. Initiative 4. Criteria for the disclosure and publication of statistical figures. Through this initiative, protocols for the disclosure and publication of criminality figures between the two agencies were established, as an input for the decision-making regarding public policy, security and citizen coexistence in the country.

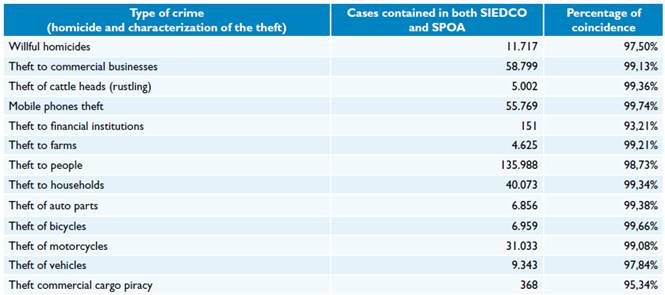

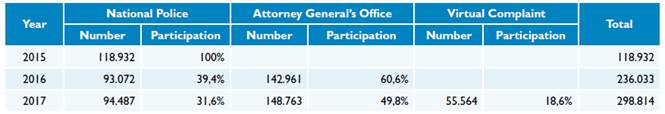

As a result of the integration and consolidation process described above, the following consolidated figures presented in Table 1 were obtained.

Table 1 Cases of homicide and theft contained in both the SIEDCO and SPOA systems, 2017

Source: National Police (2018) and COGNOS (FGN) Data Warehouse. Internal elaboration

The integration of the criminal information of the FGN and the PONAL, on homicide and theft (12 characterizations), resulted in a coincidence for 2017 in the criminal notifications of 97.50% in the case of willful homicide and 99, 28% in theft.

5. Creation of the “¡ADenunciar!” virtual complaint

By the second semester of 2016, came the idea from the National Police of carrying out the technological design called “¡ADenunciar!”. This National System of Virtual Complaint Reporting was placed into operation on July 26, 2017. This application was created in the first instance to allow victims of theft (to commerce, to people and households), information technology crimes, material with explicit child sexual exploitation content and extortion, to file a formal complaint with the authorities, through the use of a platform that is accessed through the Internet.

This virtual service is the result of interinstitutional coordination between the National Police of Colombia and the Nation Attorney General’s Office, given that this platform facilitates access to the administration of justice, starting by the completion of a series of mandatory and optional fields, regarding to the personal data of the plaintiff/victim and the description of the facts, with the option of relating witnesses and attaching material that guides the investigation and prosecution process.

Therefore, the methodology consisted in adopting and implementing standardized models for the reception of complaints, based on six crimes mentioned above, which were a pilot model for the adjustment of models and creation of criminal notifications forms, defining and characterizing them with unification of variables of both the SPOA and the System of Complaints and Contraventions (SIDENCO) of the National Police.

The fieldwork optimized the procedures, and generated that today the application, within a maximum period of 24 hours, through the judicial police officer who receives the request, validates the identity of the plaintiff, verifies that the petition meets the requirements of a criminal complaint and send for the first time to the citizen's email the Unique Criminal Notification Number; If the report is not accepted, the message that reaches the user explains the reasons for the refusal and the route that must be followed to successfully complete the process.

Then, within five (5) days term, the complainant receives an email with the information data of the district attorney's office assigned to the case; likewise, with the registration number of the report, the complaint can be followed up and its evolution can be viewed at the FGN’s website.

With this successful working methodology, we are currently working on a new replica, with the inclusion of new crimes (fraud - assault and battery - child support - domestic violence - forgery of public and private document - libel - slander - drugs trafficking and possession), which allows to strengthen the complaints reporting in the country and contribute in the process of peace construction.

“¡ADenunciar!” does not suppress the current existing complaints reception systems; on the contrary, it complements them through a web platform and an application for Smartphones (APP). Currently it is managed by the National Police, through a centralized group located in the city of Bogotá and 51 branches in the rest of the country. The centralized group is responsible for generating the guidelines for qualifying and classifying complaints received virtually, which, after a rigorous filter, are integrated into SIDENCO, which is a module of SIEDCO, and then migrate to SPOA.

Thus, “¡ADenunciar!” reduces the time from 1 hour and a half (face-to-face) to only 40 minutes (virtual), and it becomes an interinstitutional strategy that allows for the restoration of rights more promptly, so that it manages to reestablish the community's confidence back to the State’s institutions, as guarantors of coexistence and citizen security. Therefore, from the beginning it was expected that the number of criminal acts brought to the attention of the authorities would increase. In other words, a growth in registered crime was expected.

6. The consequences of the SIEDCO and SPOA information integration and the creation of “¡ADenunciar!” regarding the country's crime indicators.

The integration of information from SIEDCO and SPOA, as well as the creation of “¡ADenunciar!” were two significant processes that led to the Colombian State currently having better information available to design public policies for the prevention and reaction against crime. However, for having included methodological modifications and changes in the subject matter, both processes have implications for the comparability of crime figures over time. Following, the implications of the integration of SIEDCO and SPOA, as well as the creation of “¡ADenunciar!” are explained.

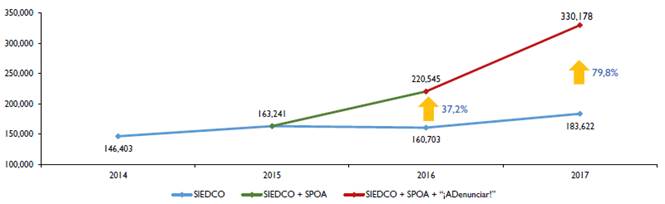

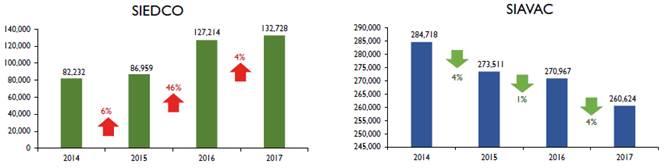

a. Consequences of integrating information from SIEDCO and SPOA

The process of integrating the 2016 and 2017 information contained in SIEDCO and SPOA resulted in the consolidation of a figure of crimes significantly greater than the figure reported by SIEDCO prior to the aforementioned integration. Figure 2 gives an example of the difference between the two figures. As can be seen in it, the number of high-impact9 crimes occurred during 2016, according to the consolidated figure after the integration of the databases, is 37.2% greater than the number of crimes of the same type occurred in said year, according to the figure reported by SIEDCO before integration. This difference becomes greater in the year 2017. As the same graph shows, the number of crimes for that year, according to the consolidated figure after the integration of the databases, is 48.9% greater than the number reported, according to the figure consolidated by SIEDCO before integration.

b. Consequences of the creation of “¡ADenunciar!”

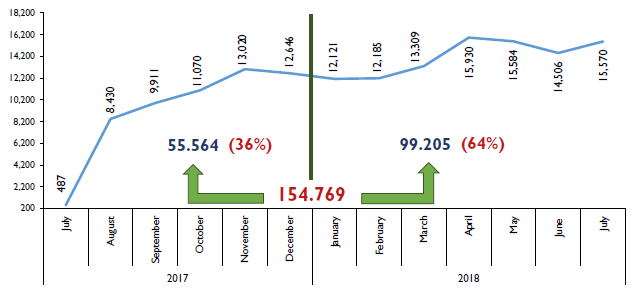

Figure 3 shows the number of complaints reported through “¡ADenunciar!” between July of 2017 and July 2018. As can be seen, the number of complaints registered in the application has followed an upward trend, going from 487 in July of 2017 to 15,570 in July of 2018. It is also important to add that the number of complaints made through “¡ADenunciar!”, during the period of time indicated (154,769), corresponds to 41.2% of the total complaints made in the country for crimes that can be reported on the platform.

Source: National Police (2018). Internal elaboration.

Figure 3 Number of complaints received through “¡ADenunciar!”, Colombia, July 2017-July 2018 (monthly)

Table 2 shows the number of offenses for the years 2015, 2016 and 2017 currently registered in the SIEDCO10 database. In addition, the table disaggregates the number of crimes according to the source of the information and indicates the participation of each source in the total of crimes of each of the three years. As can be seen, all the crimes for 2015 registered at present in the SIEDCO database were known by the National Police. On the other hand, due to the integration of the information systems of the PONAL and the FGN, 60.6% of the offenses for 2016 currently registered in the database had as their source the latter agency. Finally, the table indicates that of the total of crimes for 2017 currently contained in the aforementioned database, 18.6% had as their source the recently created application “¡ADenunciar!”; 49.8% came from the FGN, and 31.6% from the PONAL.

Table 2 Number of crimes reported through “¡ADenunciar!”, according to information source,

Source: National Police (2018). Internal elaboration.

The possibility of disaggregating the criminality information, according to its source of origin (PONAL, FGN and “¡ADenunciar!”), allows to understand how the integration of the information affects the number of registered complaints, and what are their implications on the comparability of the figures through time.

On the other hand, product of the integration of figures and the implementation of “¡ADenunciar!” as of July 26, high-impact crimes grew by 79.8% with respect to the SIEDCO database, which does not have the methodological changes (see figure 4).

Source: National Police (2018). Internal elaboration.

Figure 4 Number of high-impact crimes according to the source of the information and “¡ADenunciar!”, Colombia, 2014-2017 (annual)

When disaggregating the number of high-impact crimes for 2017, currently registered in the SIEDCO database (330,178) according to their source of the information, it is observed that 16.8% of the cases (55,564) come from complaints made through the application “¡ADenunciar!” and the remaining 83.2% (274,614) result from complaints filed through the National Police or the Nation’s FGN. It is important to note that the large number of cases reported through “¡ADenunciar!” contrasts with the fact that the application only worked during the last five months of 2017.

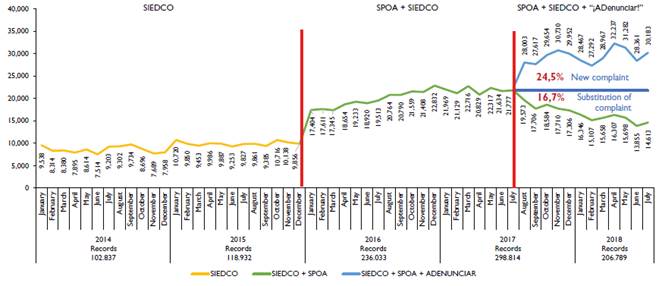

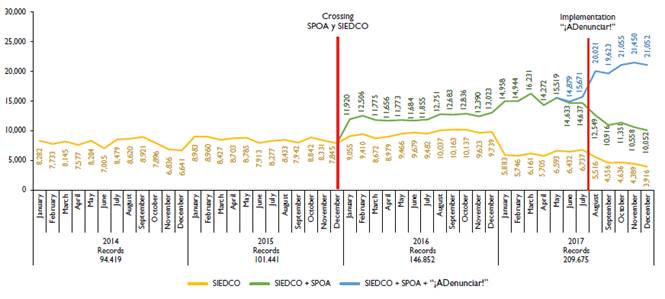

As figure 5 shows, the criminality information currently available in the SIEDCO database, corresponding to the period 2014-2015, comes exclusively from the records compiled by the National Police. On the other hand, the information corresponding to the period between July 2016 and July 25, 2017 comes from both the National Police and the Attorney General's Office (due to the integration of SIEDCO and SPOA). Finally, the graph shows that the information for the period after July 26, 2017 comes from both the National Police and the Attorney General's Office records, as well as the complaints received through the “¡ADenunciar!” App.

Source: National Police (2018). Internal elaboration.

Figure 5 Number of crimes reported in the virtual complaint according to their source of the information, Colombia, 2014-2018 (monthly). New complaint and substitution effect generated by “¡ADenunciar!”

It is important to add that the moments of integration of the aforementioned information sources coincide with changes in the trend of the time series of the crimes established11 in the virtual complaint. This shows that the increase in the number of crimes is due to the integration of the registered crime data and not the increase in real crime.

A more detailed analysis of the behavior of crime records reveals that the “¡ADenunciar!” application had a substitution effect on the use of complaint filing channels. After the start-up of “¡ADenunciar!”, the number of complaints received by the National Police and the Attorney General's Office through traditional channels began to fall, while the number of complaints filed through the application began to increase.

The above is explained by the fact that “¡ADenunciar!” reduces transaction costs incurred by citizens to file complaints. Since this application is accessed through the Internet, citizens avoid costs, such as transport to the physical locations authorized to receive complaints.

The substitution effect is quantifiable under a series of assumptions. One of these consists in supposing that, had not it been implemented, “¡ADenunciar!”, the number of complaints that would have been registered during the period between July 2017 and July 2018, through the traditional complaint filing channels, would have been equal to average number of complaints registered during the period between January and June 2017 through these channels. If the above is presumed, it is possible to infer that of the total number of complaints filed through ¡ADenunciar!”, during the period between July 2017 and July 2018 (154,769), 24.5% corresponds to complaints that would not have been filed through the traditional channels of filing complaints (new complaint), and 16.7% corresponds to complaints that stopped being made through the aforementioned channels (substitution effect). Likewise, 58.8% of the complaints were received through the traditional complaint filing channel.

c. Consequences of the integration of information from SIEDCO and SPOA, and the creation of “¡ADenunciar!”, on the comparability of the theft data to people.

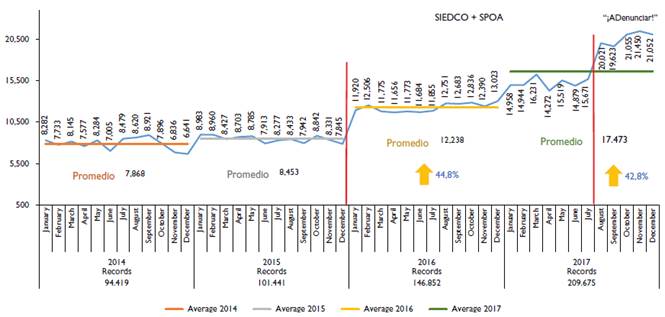

One of the crimes which behavior allows to better understand the consequences of the integration of information and the creation of “¡ADenunciar!” regarding the comparability of criminality figures, is the crime of theft to people.

Figure 6 shows the monthly time series of the number of robberies to persons registered in the country, corresponding to the 2014-2017 period. The series has two moments in which there are significant leaps in the number of recorded thefts, which coincide exactly with the beginning month of each one of the methodological changes described in this document. The first one is January of 2016, the month after which, due to the integration of SIEDCO and SPOA, the data correspond to both systems. The second moment is towards the end of July 2017, just when “¡ADenunciar!” App began operation.

Source: National Police (2018). Internal elaboration.

Figure 6 Amount of thefts to people, Colombia, 2014-2017 (monthly)

If it is not taken into account that the above-mentioned leaps are explained by the integration of the FGN and PONAL records, as well as by the creation of a new complaints filing channel, it could be erroneously concluded that between 2015 and 2016 the theft to people increased by 44.8%, and between 2016 and 2017 it did so by 42.8%.

Figure 7 disaggregates the time series of the theft to people accordingly to the source of origin of the records. The blue line corresponds to the complaints registered through the National Police; the orange line, to the complaints filed through the National Police and those registered by the Nation Attorney General’s Office. Finally, the gray line shows the complaints received through the application “¡ADenunciar!”.

Source: National Police (2018). Internal elaboration.

Figure 7 Number of thefts to people according to the source of their information, Colombia, 2014-2017 (monthly)

As noted above, the consequences of integration and aggregation of information can be separated into two stages: one between 2015 and 2016, when the change in crime figures corresponds to the SIEDCO-SPOA integration, and between 2016 and 2017, when the effects are mainly attributable to the aggregation of complaints received through the “¡ADenunciar!” Application.

Between 2015 and 2016

In 2016, 32.410 complaints coming from SPOA to SIEDCO, were added to the theft series, representing 22% of the total number of records.

The monthly average of complaints for the theft crime to people, for the year 2016 with respect to 2015, it grew up by 3,795 cases, equivalent to an increase in that average of 44.8%.

It is worth clarifying that when comparing the information of SIEDCO (blue line) in 2015 and 2016, it shows an increase of 12.8%. If, on the other hand, when the information of 2015 (blue line) is compared with the SPOA post-load information of 2016 (orange line), an increase of 44.8% in theft crime to people is mistakenly found, 32 percentage points above real increase.

Between 2016 and 2017

In 2017, the average number of complaints, product of the SIEDCO + SPOA integration and the implementation of “¡ADenunciar!”, increased by 42.8% with respect to 2016. The greater behavior of the registration of complaints resulting from the integration is due in part to the adjustment processes made during the homologation process.

Due to the implementation of “¡ADenunciar!”, it is not feasible to determine the total number of complaints that would have been received through SIEDCO and/or SPOA, due to the substitution effect of the virtual complaint with respect to the conventional complaint filing mechanisms, thanks to the savings in time and money that this generates to the victims (figure 7).

The integration process and implementation of “¡ADenunciar!” dramatically increased the registered crime contained in the official statistics (SIEDCO), not only by the aggregation of information coming from the integration process, but also by the benefits that the use of technology represents for the victims in the complaint filing process of the crimes of which they were victims (figure 7).

In addition, when comparing the records from SIEDCO + SPOA + “¡ADenunciar!”, from the August-December period, a growth of 62.1% is observed during 2017, with respect to the same period of 2016. Taking the segment of 2017, “¡ADenunciar!” app has a participation in theft crime to people of 23,6%, with respect to the total number of registrations during that year.

d. Contrast of the SIEDCO figures and those of other sources of information

One of the questions that may arise due to the changes observed in the criminality figures of the country is whether these are the result of the integration and aggregation of information or increases in the real crime. Beyond warning - as it was already done - that there is a correlation between the increase in the crime figures and the introduction of the aforementioned changes, the previous question can be answered by contrasting the SIEDCO figures with those of other sources of information that register similar criminal variables and which have not had changes in their forms of measurement during the last three years.

For this purpose, this subsection contrasts SIEDCO figures with those of the following sources: 1) some victimization surveys from the main cities of the country; 2) the database of cell phone theft of ‘El Corte Inglés - The English Cut’ Department Store, and 3) the interpersonal violence database of the Colombian Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences.

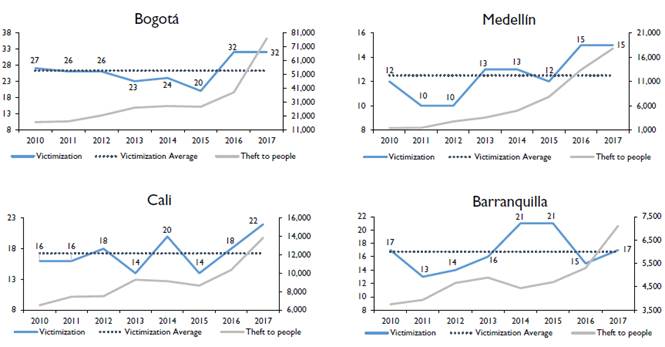

i. The incidence of crime according to victimization surveys

Victimization surveys12 offer information about the crimes that individuals are victims of. Taking into account that the theft to people is one of the crimes that has the highest incidence amongst the population, it is possible to use information on the percentage of people who report having been victims of a crime during the last year (according to the victimization surveys), to compare the data registered in the SIEDCO13. If the increase of 42.8% in the records of robbery to persons for 2017, currently registered in the SIEDCO, was associated with increases in the criminality, this increase should be reflected in an increase in the percentage of people who report having been victims of crimes.

Figure 8 shows the behavior of victimization and theft to people in the four main cities of the country during the period 2010-2017. In the graph it can be seen that while official records of theft to people grew in all cities, between 2016 and 2017, the victimization did not increase systematically. For example, while in Bogota and Medellín the number of registered thefts to persons grew, in their order, 102.6% and 32.7%, between 2016 and 2017, the percentage of people surveyed who said they had been victims of a crime remained more or less stable in both cities (at levels close to 32% and 15%, respectively).

Source: National Police (2018), Bogotá how are we doing, Medellin how are we doing, Cali how are we doing, Barranquilla how are we doing. Internal elaboration, 2018.

Figure 8 Victimization and theft to people, Bogotá, Medellín, Cali and Barranquilla, 2010-2017 (annual)

The foregoing is evidence that the increases in the numbers of theft to people are the result of the integration and aggregation of information, but not increases in real crime.

ii. The theft of cell phones according to ‘El Corte Inglés - The English Cut’ Company

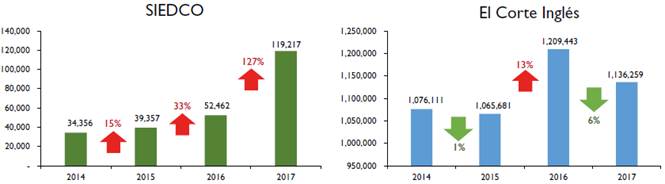

At the national level, the most stolen object to people is the cell phone: 55% of the reports of theft to people are for cell phone theft. Before the integration of SPOA and SIEDCO information, as well as the creation of the “¡ADenunciar!” App, the number of cell phone theft records increased by 2% between 2013 and 2014, and by 15% between 2014 and 2015. After the aforementioned changes, the number of records of this type of theft increased by 33% between 2015 and 2016, and by 127% between 2016 and 2017.

In compliance with the government's strategy against cell phone theft, and pursuant to article 106 of Law 1453 of 2011 and Resolution CRC (Communications Regulation Commission) 3128 of 2011, the companies providing mobile communications services in Colombia register cell phones stolen in the Negative Data Base14, through the computer company ‘El Corte Inglés S.A. - The English Cut Inc.’

The cited database constitutes a valuable source of alternative information, due to the fact that it has not had variations in its structure or in the methodology through which the compiled information that is recorded in it is collected on cell phone theft, reported by the users of the different operators.

Taking into account the above, if the increase in the number of cell thefts registered in the SIEDCO database is the result of an increase in real crime, it is to be expected that the number of thefts registered in the database of ‘El Corte Inglés - The English Cut’ has also had an increase.

Contrary to the above, figure 9 shows that the behavior of the number of mobile theft records between 2016 and 2017 is different in one and another database. While the records of the SIEDCO database increased by 127%, those of the ‘El Corte Inglés S.A. - The English Cut Inc.’ database. decreased by 6%. This confirms that the increases in the figures recorded in the SIEDCO database are due to the integration of the information and the creation of “¡ADenunciar!”, and not to an increase in real crime.

iii. Interpersonal violence according to the Colombian Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences

During the last four years, the behavior of personal injuries due to assault and battery registered in the SIEDCO database has shown a trend opposite to the behavior of interpersonal violence registered by the IMLCF.

In the SIEDCO, personal injuries have shown an upward trend from 2014 through 2017, with a high increase of 46% between 2015 and 2016, as a result of the integration of information from SIEDCO and SPOA15.

On the contrary, the INMLCF16 records show that interpersonal17 violence has followed a downward trend during the last four years, with a decrease of 1% between 2015 and 2016 (figure 10).

Source: National Police (2018) and INMLCF. Internal elaboration.

Figure 10 Number of personal injuries and cases of interpersonal violence, Colombia, 2014-2017 (annual)

Following the logic indicated above, if the increase in the SIEDCO personal injury records, which is observed between 2015 and 2016, were the result of an increase in real crime, it is to be expected that the interpersonal violence figures of the INMLCF would also show an increase during the indicated period. However, as shown in figure 10, the figures for interpersonal violence do not increase, which confirms that the increase in personal injury records in the SIEDCO database is due to the integration of the SIEDCO information and the SPOA, described throughout this article.

7. Conclusions

In accordance with the guidelines of multilateral organizations, during the last few years the Colombian government has developed policies aimed at improving the country's information systems, with the objective of improving the quality of the information available to make public policy decisions.

As a result of the foregoing, the Institutional Strategic Plan PONAL and FGN allowed the consolidation of statistical figures related to the complaints filed by the victims of conducts classified in the Colombian Criminal Code. This process has constituted an important advance in the institutional synergy related to the processes of collection, processing, analysis and disclosure of statistical information.

The institutional synergy not only generated a unification of the crime figures, but also improved the quality of the statistical data and enabled the implementation of the complaint filing “¡ADenunciar!” App.

Although the integration of information from SIEDCO and SPOA, and the creation of the “¡ADenunciar!” App, improved the quality of criminality data available in the country and reduced under-filing (the “¡ADenunciar!” App, also improved the access to justice on the part of the citizens), both changes pose challenges for the monitoring of the country's criminality indicators over time. In other words, the criminality information recorded in the SIEDCO database lost its comparability over time, as a consequence of the aforementioned changes.

Taking into account the above, this article has tried to explain the process of information integration and its consequences on the comparability of the country's crime figures over time. The analyzes carried out throughout the article allow us to conclude that the increase in the country's criminality indicators was the result of the increase in the number of records registered in the SIEDCO. This increase was due, not to the increase of real crime, but to the integration of the criminality information known to the FGN and those that the PONAL knew jurisdiction. Likewise, the increase in the number of records was the result of the creation of the “¡ADenunciar!” App, which reduced the transaction costs incurred by citizens to file complaints. Despite the comparability issues generated, the integration of information from SIEDCO and the SPOA, as well as the creation of the “¡ADenunciar!” App, constitute important advances that the country had to make in order to have a greater and better quantitative information on criminality.

REFERENCES

Aguilar, M., Patró, R. & Morillas, D. (2014). Victimología: Un estudio sobre la víctima y los procesos de victimización. Madrid: Dykinson. [ Links ]

Barranquilla cómo vamos (2018). Encuesta de Percepción Ciudadana Barranquilla 2008-2017. Barranquilla. [ Links ]

Bottoms, A. & Tankebe, J. (2012). Beyond procedural Justice: A dilogic approach to legitimacy in criminal justice. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 102 (1): 119-170. [ Links ]

Buitrago, J. & Norza, E. (2016). Registros de la criminalidad en Colombia y actividad operativa de la Policía Nacional durante el año 2015. Revista Criminalidad, 58 (2): 9-20. [ Links ]

Buitrago, J., Rodríguez, J. & Bernal, P. (2015). Registros administrativos de Policía para la consolidación de cifras de criminalidad en Colombia. Revista Criminalidad, 57 (2): 11-22. [ Links ]

Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá (22 de junio del 2018). Encuesta de percepción y victimización. Recuperado de https://www.ccb.org.co/Transformar-Bogota/Seguridad/Observatorio-de-Seguridad/Encuesta-de-percepcion-y-victimizacion [ Links ]

Centro de Excelencia para Información Estadística de Gobierno, Victimización, Seguridad Pública y Justicia; C de unodc; (14 de diciembre del 2015). La cifra oscura y las razones de la no denuncia en México. Recuperado de https://cdeunodc.wordpress.com/2015/12/14/la-cifra-oscura-y-los-razones-de-la-no-denuncia-en-mexico/ [ Links ]

Código de Buenas Prácticas de las Estadísticas Europeas (28 de septiembre del 2011). Recuperado de http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3859598/5922097/10425-ES-ES.PDF [ Links ]

Consejo Económico y Social de la Organización de las Naciones Unidas ;ONU; (2009). Resolución 2009/25. Mejoramiento de la reunión, la presentación y el análisis de información para aumentar los conocimientos sobre las tendencias en esferas delictivas concretas. Recuperado de: http://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/Crimedata-EGM-Feb10/ECOSOC-Resolution-2009-25_Spanish.pdf [ Links ]

Constitución Política de Colombia (1991). Senado de la República. Recuperado de http://www.senado.gov.co/images/stories/Informacion_General/constitucion_politica.pdf [ Links ]

DANE (22 de junio de 2018a). Encuesta de Convivencia y Seguridad Ciudadana ECSC 2015. Recuperado de https://formularios.dane.gov.co/Anda_4_1/index.php/catalog/390 [ Links ]

DANE (22 de junio de 2018b). https://www.dane.gov.co/files/investigaciones/victimizacion/formulario.pdf. Recuperado de https://www.dane.gov.co/files/investigaciones/victimizacion/formulario.pdf [ Links ]

Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística ;DANE; (julio del 2004). Aspectos metodológicos para la construcción de Línea Base de Indicadores. Recuperado de http://www.metropol.gov.co/observatorio/Expedientes%20Municipales/Documentos%20tecnicos/Aspectos_Metodologicos_Indicadores_Linea_Base.pdf [ Links ]

Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística ;DANE; (julio del 2004). Dirección de Regulación, Planeación, Normalización y Estandarización - DIRPEN. Recuperado de http://www.metropol.gov.co/observatorio/Expedientes%20Municipales/Documentos%20tecnicos/Aspectos_Metodologicos_Indicadores_Linea_Base.pdf [ Links ]

Departamento Nacional de Planeación ;DNP; (2014). Bases del Plan Nacional de Desarrollo 2014-2018. Todos por un nuevo país, paz, equidad, educación. Recuperado de https://www.minagricultura.gov.co/planeacion-control-gestion/Gestin/Plan%20de%20Acci%C3%B3n/PLAN%20NACIONAL%20DE%20DESARROLLO%202014%20-%202018%20TODOS%20POR%20UN%20NUEVO%20PAIS.pdf [ Links ]

Medellín cómo vamos (2018). Recuperado de: https://www.medellincomovamos.org/download/infografia-informe-de-calidadde-vida-de-medellin-2017/?utm_source=Documentos%20Home&utm_medium=Botones%20Sidebar&utm_campaign=Infograf%C3%ADa%202017&utm_term=Informe [ Links ]

Ministerio de Justicia y del Derecho, Agencia Presidencial de Cooperación Internacional de Colombia, Unión Europea (2012). Informe Final, Diagnóstico y Propuesta de Lineamientos de Política Criminal para el Estado Colombiano. Bogotá. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Justicia y del Derecho, PONAL, INMLCF & FGN (2017). Plan Decenal del Sistema de Justicia 2017-2027. Bogotá. [ Links ]

Nix, J. (2015). Police Perceptions of Their External Legitimacy in High and Low Crime Areas of the Community. Crime & Delincuency, V. 63: 1250-1278. [ Links ]

Norza, E., Peñalosa, M. & Rodríguez, J. (2017). Exégesis de los registros de criminalidad y actividad operativa de la Policía Nacional en Colombia, año 2016. Revista Criminalidad, 59 (3): 9-40. [ Links ]

Oficina de las Naciones Unidas contra la Droga y el Delito ;UNODC; (marzo del 2015). Clasificación Internacional de Delitos con fines Estadísticos. Versión 1.0. Recuperado de https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/statistics/crime/ICCS/ICCS_SPANISH_201 [ Links ]

Policía Nacional de Colombia (2018). Registros administrativos de delitos y denuncias. Sistema de Información Estadística, Delincuencial, Contravencional y Operativa (SIEDCO). Bogotá. [ Links ]

PONAL (2015). Conductas y servicios de Policía. Bogotá: DANE. [ Links ]

Redondo, S. & Garrido, V. (2013). Principios de Criminología (4.ª ed.). Valencia: Tirant Lo Blanch. [ Links ]

Restrepo, J. (2008). Cincuenta años de criminalidad registrada por la Policía Nacional. Criminalidad 50 años, 26-35. [ Links ]

Sistema Estadístico Europeo (28 de septiembre del 2001). Código de Buenas Prácticas de las Estadísticas Europeas. Recuperado de http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3859598/5922097/10425-ES-ES.PDF [ Links ]

Tyler, T. (1990). Why people Obey the Law. New Haven: Yale University Press [ Links ]

2The purpose of the FGN and the PONAL is to continue later on with sexual crimes, fraud and threats.

4Statistical operation of the administrative records for statistical purposes of crimes and operational activity carried out by the National Police.

6The criminal notifications of theft are classified as: theft to people, households, commercial businesses, financial institutions, farms, to vehicles, cell phones, auto parts, bicycles, motorcycles, cattle rustling and road piracy.

9The high-impact crimes are: assault and battery, theft (to people, households, commerce, financial institutions, of vehicles, motorcycles, for road piracy and cattle rustling) and homicide.

10The high-impact crimes are: assault and battery, theft (to people, households, commerce, financial institutions, of vehicles, motorcycles, for road piracy and cattle rustling) and homicide.

11Theft (to commerce, to people and to households), information technology crimes, material with explicit content of child sexual exploitation and extortion.

13In the following analyzes presented below, only the results of the question of victimization surveys are used, which inquires whether the person interviewed was a victim of a crime during the last year.

14The database is fed by the victims, who through the operators report the theft of cell phones, in order to block the IMEI and relief from the responsibility for it.

15It is important to note that personal injuries were only subject to the change resulting from the integration of information from SIEDCO and the SPOA, because these cannot be reported through the “¡ADenunciar!” App

16This source has not had modifications or integrations of information in its database during the last two years.

To cite this article / To reference this article: Rodríguez, J. D., Mejía, D., Caro, L., Romero, M. & Campos, F. (2018). Implications of the process of integration of the administrative records of criminality between the Attorney General's Office SPOA system and the National Police of Colombia SIEDCO system, and the implementation of the "¡ADenunciar!" application on the criminality figures. Criminality Magazine, 60 (3): 9-27

Received: January 12, 2018; Revised: April 18, 2018; Accepted: May 21, 2018

texto em

texto em