Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Revista Criminalidad

versão impressa ISSN 1794-3108

Rev. Crim. vol.60 no.3 Bogotá out./dez. 2018

Estudios Criminológicos

Measuring crime: criminality figures and police operations in Colombia, 2017

1Doctorando en Derecho de la Universidad de los Andes. Magíster en Derecho Penal. Universidad de los Andes. Bogotá, D. C., Colombia. fernandoloentamayo@hotmail.com

2Doctorando en Ciencia Política de la Universidad de los Andes. Magíster en Criminología y Victimología. Jefe del Observatorio del Delito. Dirección de Investigación Criminal e Interpol, Bogotá D.C., Colombia. Ervyn.norza@correo.policia.gov.co

This analysis comes from a descriptive exercise of the criminal administration records obtained by the National Police of Colombia. Crimes of the country are characterized during 2017 and the main changes at subnational level are indicated, especially homicide. This crime continues the decreasing trend to one of the lowest rates in the country’s history, 25 per 100,000 population. The operational activity of the National Police is described as an outcome of the fight against crime in containment and disruption logic of crime. Similarly, the result of the National Police Code implementation is indicated through regulation and the improvement for citizen coexistence with regard to the contradictory behaviors to this issue. Finally, 38 tables are annexed that provide the reader with a national, regional and local overview of the National Police records to study crime.

Key words: Criminal statistics; complaint; crime; Police; police statistics (Source: Tesauro de política criminal latinoamericana - ILANUD). Administrative records.

Como resultado de un ejercicio descriptivo de los registros administrativos de criminalidad obtenidos por la Policía Nacional de Colombia, se caracterizan los delitos en el país durante el año 2017 y se indican los principales cambios a nivel subnacional -en especial del homicidio, delito que mantiene la tendencia hacia la disminución y una de las tasas más bajas de la historia del país, equivalente a 25 por cada 100.000 habitantes-. También se describe la actividad operativa de la Policía Nacional. Asimismo, se indica el resultado de la aplicación del Código Nacional de Policía con respecto a los comportamientos contrarios a la convivencia; y, finalmente, se anexan 38 tablas que brindan al lector una mirada nacional, regional y local de los registros de la Policía Nacional para analizar el delito.

Palabras clave: Estadísticas criminales; denuncia; delito; Policía; estadísticas policiales

Como resultado de um exercício descritivo dos registros administrativos de criminalidade obtidos pela Policia Nacional da Colômbia, se caracterizam os delitos no país durante o ano 2017 e se indicam as principais mudanças em nível subnacional, em especial do homicídio, delito que mantém uma tendência à diminuição e uma das taxas mais baixas da história do país, equivalente a 25 para cada 100 mil habitantes. Se descreve a atividade operacional da Policia Nacional como resultado da luta contra o delito na lógica da contenção e da interrupção das formas do crime. Assim mesmo, no componente da regulação e o melhoramento da convivência cidadã, se expõe o resultado da aplicação do Código Nacional da Policia em relação aos comportamentos contrários à convivência e, finalmente, se anexam 38 tabelas que oferecem ao leitor uma perspectiva nacional, regional e local dos registros da Policia Nacional para analisar o delito.

Palavras chave: Estatísticas criminais; denúncia; delito; Policia; estatísticas policiais

Introduction

This paper aims to describe the behavior of criminal activity in Colombia in 2017 and to provide tools for national and international investigators who study crime from different perspectives and who require dependable information about criminal situations and police actions in the national territory. To provide a context of data, this paper presents the current discussion about the impact measurement of police activity and argues that an appropriate study of this topic depends on the correct database consolidation to know criminality.

This article is divided into three additional sections to this introduction. The first section presents the current discussion about the impact measurement of police activity in both national and international context. It shows how it depends on available criminal statistics. This section is also divided into three subsections. Firstly, is described the main assumptions that the task of measuring criminal activity makes and some of the ways to approach these challenges to improve data quality. The second subsection analyses the investigations about the topic and the results they have produced. The third subsection describes the national discussion by which criminal activity is measured and the way National Police has been compiling data. Additionally, the second section of the article develops a descriptive analysis of the main criminal and operational indexes used by the National Police during 2017. The third section offers some conclusions identifying relevant concerns for local criminality investigations, which contribute to the empirical knowledge production about actions taken to diminish crime1.

Considerations about the impact of the police activity in criminality

a. The development of the measurement of the police activity impact

The criminality measurement and the actions to reduce it offer a particularly high degree of complexity, which are different to the issues measurement of State intervention. While the measurement of issues, such as unemployment or education, are normally more dependent on the measurement criteria type and on the institutional capacity to collect accurate information -The figures of these topics have an acceptable level of reliability when there is precision about the measurement method and a good capacity of gathering data-. The diversity of the criminal phenomenon requires counting with measurement tools, which are continuously changing.

The complexity of crime measurement and the impact of programs to reduce it emanate from different factors. Firstly, from the way that the punitive system exists in contemporaneous western society, secondly from different mechanisms that are carried out to manage the deterrent of crime and thirdly from challenges that presented by matter of data collection.

About the first issue, beyond the complexity of the punitive systems whose characteristics cannot be approached in this paper, in great part, the western punitive systems are ruled by the legality principle, in both wide and strict senses. Thus, it is resulting in that only can be considered criminal those issues defined by the legislator (De Vicente Martínez, 2006; Velásquez, 2013; Ferrajoli, 2011). The fact that the capacity of defining the criminal is based exclusively on the legislator has brought different implications. On the one hand, the measurement of criminality is normally subjugated to the crimes legal definitions. It happens at a historical moment of a permanent expansion and amendment of the Penal Law (Silva Sánchez, 2001; Sotomayor Acosta & Tamayo Arboleda, 2014). Above statements not only make difficult to document certain events, but also it is hard to consolidate figures under fixed categories, because the crime and its definitions change rapidly. Hence, democracy problems reappear in the criminality definition, that is to say, different power relationships that take to the popular representatives’ election, who define and adjust the way of characterizing criminality. Therefore, “criminality” becomes a defined scope according to the historical context of the country and the different interests of certain groups of power.

With regard to the second issue, it is necessary to consider that there are diverse mechanisms to reduce criminality. Although, the business of governing crime is usually represented in the institutions of the punitive system, it does not imply that they are the only ones capable of intervening in this matter. Even if, the visible institutions of the punitive system -legislator, justice administration, Police and prison- are centrals in the contemporaneous government of crime, other mechanisms have always accompanied this task. The labor market (Rusche & Kirchheimer, 1984; Wacquant, 2012), educational settings (Simon, 2011) and religion (Durkheim, 1969), among other mechanisms, make part of a social control net built to intervene crime. This makes difficult to isolate specific actions undertaken to reduce criminality and, with this, to measure their impact in this task becomes difficult.

In addition to the above, the great quantity of new arrangements and self-government and security mechanisms of the criminality are added, which have appeared since the last past quarter of the last century; and they proliferate until today -private security organization, security cameras, alarms, self-care policies linked to citizens everyday practices, closed units, among others (Garland, 2005; Young, 2003; Bauman, 2015)- that complicate even more knowing the appropriate actions to reduce crime and which of them are only appearance.

In third place, the measurement of criminality presents diverse challenges that cannot even face through the institutional capability increase for collecting data, because there are always crimes that escape from the institutional lens, it can be because of the criminal report nonexistence or due to simple lack of knowledge of the facts. The called “off-the-record” or “crime dark figures” (De Folter, Steinert, Scheerer, Mathiesen, Christie & Hulsman, 1989) make suspect that there are always under-records of the crime figures, and that every rise of the institutional capability to collect data can take to report a growth in the criminality, not necessarily because it has actually increased, but because the crimes percentage remaining outside the institutional knowledge is reduced. Although, this situation is only hypothetical, it becomes plausible and makes possible to consider that criminality reports are increasing not because the security is worsening, but because of the ability of approximation to its actuality is improved, or due to reports on failure of different programs of crime control are just mere noisy generated by the rise of capacity for detecting criminality.

In Colombia, for example, the unification of the figures between the National Police and the Office of the Attorney General of the Country, and the implementation of mobile applications to report crimes increased drastically the criminality records. It does not necessarily implies a growth in criminality (although this hypothesis cannot be discarded), but an increase of the institutional capacity to detect facts that were not in the radar. One example of this is that in Bogotá city, while in 2015 all the criminal reports belong to the National Police database, in 2016 the recorded crimes were known starting from the data provided by the National Police database (70% of the total) and the Office of the Attorney General of the Country (30% of the total); and, in 2017, these percentages have varied to 50% and 25%, respectively, and the online systems of crime complaints reported 25% of the cases (Office of the Mayor of Bogotá, 2018). In this way, in only two-years period, it seemed the National Police has doubled its capacity for recording the crime reality in Colombia, which evidences (at least partly) the recorded increases (Office of the Mayor of Bogotá, 2018).

The Police and the necessity of measuring its own impact in crime control arise to measure the criminality in the mist of the difficulties. This organization depends doubly on that those measurements can be carried out in an appropriate way. On one hand, being an institution in charge of maintaining the public order, an accurate knowledge of crime is a fundamental element to formulate different strategies of intervention with regard to it (Norza, 2017). On the other hand, the pressure for satisfying certain goals on criminality reduction makes that the Police actions impact measurement becomes central to determine what is useful and what is not, as well as the ways to improve actions. All of these issues make that determining the incidence of different programs of criminality reduction comes to be a complex task.

Among the many tools that can be used to intervene crime (implementation of subsidies, education, construction of social fabric, among others), certainly the Police is a central actor. Police activity has attempted to being measured for a long time, and the initial conclusions were not encouraging. During the XX century, different studies seemed to stress that this institution did not have any usefulness to combat crime. Bayley asserts,

The police do not prevent crime. This is one of the best kept secrets of modern life. Experts know it, the police know it, but the public does not know it. Yet the police pretend that they are society’s best defense against crime an continually argue that if they are given more resources, especially personnel, they will be able to protect communities against crime. This is a myth (Bayley, 1994, 3)2.

Other studies were joined to Bayley’s assertions. These studies measured the impact of Police in criminality, but they did not produce outcomes that allowed connecting the police action to crime reduction (Lindström, 2013; Pare, 2014). Only few investigations attributed to Police some success capacity on criminality reduction (Ehrlich, 1973; Philips 1977; Gatrell, 1980). However, this situation would begin to change rapidly through proliferation of studies that measured the police action and attributed a variable function in reducing criminality figures.

Marvell and Moody’s studies (1996), and above all the seminal studies of Levitt of the topic (1995, 1998), would be the beginning of works in charge of the police activity measurements. These studies would report a negative relation between the improvement of the institution and the criminality figures. In his work paper “Why do increased arrest rates appear to reduce crime: deterrence incapacitation or measurement error?” Levitt (1995) approaches diverse methodological problems of the police activity measurements, which have led to underreport the institution success in the task of controlling crime. Levitt states some problems of measurement that, although they seem evident, they were not taken into account in the previous measurements. In the first one, he asserts that it is necessary to disregard the police action as an isolated event and that; instead, it is required to consider it as a part of the general action of punishing. It leads to stress that it is required to include possibilities so that the arrest results in condemn and, subsequently, in prison, for measuring in an appropriate way the police activity.

Once aforementioned is considered, the author assumes necessary to differentiate the dissuasive effects of the police action in accordance with the prison, from the effects, which are merely incapacitating. In other words, he stresses that it is essential to search modes for determining how many crimes are not committed because the individuals want to avoid the costs of being immersed in a penal process and how many crimes are not committed because the individuals imprisoned are immobilized in a temporal way. Therefore, these individuals assuming their connection to a criminal career stop committing crimes while they are behind jail bars. The second issue shows the complexity of working with reported crimes instead of real crimes, since it makes that the measurements do not correspond to the reality. However, the author argues that it is an issue that can be overcome methodologically.

In his text, Levitt concludes that the police action reduces the criminality, both at deterrence and incapacitation levels. He emphasizes that the Police have a greater effect on crime reduction during deterrence phases than through incapacitation. Since police effectiveness seems to be greater during deterrence, it is suggested that progressive laws of tightening, such as the well-known three strikes and you’re out3, should be implemented. This is because this type of legislation has a greater capacity of serving as a criterion of deterrence of the laws, whose severity is implemented from the first arrest (Levitt, 1995: 31). The idea that the police capacity did not depend on the incapacitation, that is, of the activation of the penal system to incarcerate criminals, but it was manifested mainly through the deterrence; that is to say of the capacity of reducing criminality through the presence or control activities held in certain locations. This refuted Bayley’s statements about the uselessness of the Police. Rather, in its place, it is a stronghold of crime control. Marvell and Moody (1996) continued with Levitt’s study. They arrived at the same conclusions of this author with some methodological corrections. What this means is that both studies conclude that more police officers (in amount and activity) lead to less crime. Levitt himself validated this hypothesis in two subsequent studies (1998, 2002).

After the emergence of these studies mentioned above, a methodological corrections wave came in relation to the method of measuring the police impact, and likewise a flood of information that confirmed the initial Levitt’s assertions. On one hand, different studies of measurement of police action and strategies developed by this entity appeared. Investigations results were shown and were reported by Braga, Weisburg, Waring, Mazerolle, Spelman and Gajewsky (1999); Braga, Papachristos and Hureau (2001); Braga (2005); Weisburg and Eck (2004); Braga and Bond (2008); Braga, Papachristos and Hureau (2014); Williams, Linden, Currie and Donelly (2014), among others.

All the previous studies, reported success of different police programs. In this line, for example, studies of Braga, Weisburg and Turchan (2018) show how pulling levers4 strategies have reported a criminal reduction; Braga, Papachristos & Hureau (2001) and Weisburg and Eck (2004) demonstrate how the focused police action has reduced criminal figures. Papachristos and Kirk (2015) show how recognition and inclusion of criminal gangs’ members in the task of reducing homicide violence had positive impacts in Chicago5. Pare (2014) demonstrates, in a study conducted in 77 countries, the way police performance is connected to minor levels of homicide violence. In addition, he suggests that in the countries where Police has a high index of action with regard to the homicide, a better perception among victims and citizens who, in general, are satisfied with Police performance, there is a positive effect on the crime reduction.

On the other hand, studies related to the economic investment and police efficiency emerged such as the studies conducted by Chalfin and McCrary (2012). They argue that there is a negative relationship between the capitalization of the police forces and criminality, it implies, to a greater investments in these forces, better results are emerged in reducing crime indexes. Parra Domínguez, García Sánchez and Rodríguez Domínguez (2013) report that the police efficiency had negative influence in the crime indexes, therefore a better destination of resources and the increase of the investment in the entity would mean an improvement of the security conditions. Lindström (2013), stresses that there is a negative relationship between the increase of the police forces and the criminality figures, with this, with a greater number of police officers there would be a greater reduction of crime.

Despite the increasing amount of literature reporting the success of the Police as a tool to reduce criminality, concurrently, a discussion has been open in relation to the capacity of these studies to approaching reality. On one hand, methodological difficulties of these texts are reproached, either because of the limited reliability or because the construction of models of impact measurement normally implies doubtful theoretical assumptions. In terms of reliability of the collected data, criticism is not based on incorrect methods of gathering data. Rather, the limitation of the data observed is the main issue since it shows a fragment of reality. For example, some studies normally use national level figures to compare countries (E.g. Pare, 2014; Parra Domínguez, García Sánchez and Rodríguez Domínguez, 2013). Thus, these studies tend to generalize infinitely complex realities -think, for example, GINI index, which reflects country inequality, it does not display that the same one can operate in different countries, or in different settings, such as cities or small towns)-. On the other hand, in relation to the theoretical assumptions, many measurements are based on unverified theories that emanate as assumptions that ideologize models apparently objective, such as the rational election theory. Situations, as the ones mentioned above, have led some authors to criticize the measurement models developed or they persevere in demonstrating empirically or theoretically the limited effectiveness of Police in influencing criminality (Eck & Maguire 2000; Garland, 2005; Deadman & McDonald 2002; Tonry, 2011; Wacquant, 2012). In addition, there are authors who, beyond the effectiveness or not of the police action and the punishment system, argue that police activity and prison should be reduced due to the high human costs that it implies (Liedka, Piehl & Useem, 2006; Steen & Bandy, 2007; Simon, 2011; Raphael, 2014; Mitchell, 2014).

As it is evidenced, the measurements of the effects of the actions against criminality have different ways of approaching. The challenge is to identify the explicative causal relation. Thus, in many opportunities variables are connected to crime reductions without conducting evaluations of impact or identifying empirical evidence. Consequently, the strategies design of security and police actions based on the evidence is the approach that must be indicated. This situation is developed in the National Police of Colombia through the Crime Observatory implementation. Thus, the method of observing data and approaching the criminal conduct is improved. This article is an example of it and aims to provide policy makers and crime analysts with elements.

b. Impact measurement of the police activity in Colombia

The general discussion has been provided on the Police incidence in the criminality figures, with certain similarity, in the Colombian context. On one hand, the National Police holds a complete information bank. National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE) certifies the quality of this information bank. Though, this quality recognition is a good launch, there are still some measurement problems in diverse crimes that make, in spite of the appropriate figures, it lacks of some relevant information of the topic. In this way, the National Police has sought to be reinforced through the unification of figures with the Office of the Attorney General of the Country (Rodríguez, Romero Hernández, Caro Zambrano & Campos Méndez, 2018), but this labor requires to be further strengthened.

The measurement of the capacity of police activity to reduce crime has been approached in some Colombian texts. The book Las cuentas de la violencia (The counts of violence) performs an important role in the impact measurement task of the police actions in criminality. This book includes studies of Sánchez, Espinosa and Rivas (2007) and Sánchez and Moreno (2007). The first one of these studies analyses the impact of the implementation of preventive and police measurements, and compare the areas in which each one of them had impact. The second study analyses the impact of the implementation of the mass transport system TransMilenio on the Caracas Avenue in Bogotá. Different reports follow these studies that analyzed mechanisms geographically located of police intervention (Ideas Foundation for Peace, 2012; Ideas Foundation for Peace, Inter-American Development Bank and the National Police, 2014; Office of Information Analysis and Strategic Studies, 2016, 2018a and 2018b; National Police, 2012; Bulla & Ramírez, 2016), the evaluation of specific policies implementation against certain crimes (Bulla, García, Lovera & Wiesner, 2016; Escobedo, Ramírez & Sarmiento, 2017; Mejía, Restrepo & Rozo, 2017, Blattman, Green, Ortega & Tobón, 2017), or the impact measurement of other realities, such as economy or new technologies in the control of crime (Beltrán & Salcedo Albarán, 2014; Mejía & Restrepo 2016; Gómez, Mejía & Tobón, 2017).

Studies above report the success of the police actions to face criminality. For example, the studies of Sánchez and Moreno (2007) and Sánchez, Espinosa and Rivas (2007) show figures that have credited the National Police a high capacity of deterrence. Although, previous studies do not include in their variables to the fall of violence related to drugs trafficking in Bogotá. These studies have left aside the impact that the police actions against Pablo Escobar (and his own death) or the drug cartels war disappearance had in the violence decrease in the city. They are interesting models that open the path for conducting studies that are more complete.

Other studies are cautious in the scope of their assertions, but they are aware that the National Police has had an enormous incidence in reducing criminality, because, although there are sectors where the improvement is moderate, the decrease of criminality emerging from the police action is transcendental. Also, it emerges the analysis of policies that are geographically directed to intervention, which are linked to the focus strategies in hot spots and vigilance for quadrants (Ideas Foundation for Peace, 2012; Office of Information Analysis and Strategic Studies, 2016; Office of Information Analysis and Strategic Studies, 2018a; Office of the Information Analysis and Strategic Studies, 2018b), which report an improvement of the security conditions in the city and stress the need of complementing, both the studies and the police interventions with social tools targeted to reducing criminality.

Meanwhile, Bulla and Ramírez (2016) have shown the positive impact of the National Police, and have suggested the extension of social programs for reducing crime. In addition, Mejía, Ortega and Ortiz (2014) have measured the contemporaneous reality of the crime in Colombia and have ratified that police reinforcing and the institutional action focus have had positive impacts in reducing crime. As a final example, the National Police (2012) and the Ideas Foundation for Peace (2012) have evaluated the implementation of the National Plan of Community Vigilance for Quadrants, and have shown that a decrease in criminal violence has been experienced in most of the settings where this geographic policy of police control has been executed.

Despite the success reports in these studies, other analyses have been conducted in Colombia. These analyses fail in considering factors that would inquire upon police effectiveness. In other cases, they directly show other types of interpretations where the Police reduces the incidence of criminality. In the first group are such studies like the one conducted by Sánchez and Moreno (2007), which reports figures of crime reduction close to 90%. This analysis, focused on the intervention of Caracas Avenue in regard to the mass transportation system TransMilenio. Important factors are not included in this study, such as the reduction of violence related to drug trafficking. In this study, the spatial displacement of crime is considered in an inappropriate way. Thus, a simplistic view of neighboring blocks is included; despite the fact they do not have the same social and commercial structure as Caracas Avenue. In the second group, there are different studies that query the effectiveness of police actions. These studies include those done by the Ideas Foundation for Peace (2012) and the Office of Information Analysis of Strategic Studies (2016; 2018a; 2018b) are among them.

In addition to the strategies of the National Police that have been measured by the authors referred on the last paragraphs, there are different policies addressed to criminality reduction whose impact is still to be measured. On one hand, it is possible to extend the existing measurements (Blattman, Green, Ortega & Tobón, 2017; Ideas Foundation for Peace, 2012; Office of Information Analysis and Strategic Studies, 2016; Office of Information Analysis and Strategic Studies, 2018a; Office of Information Analysis and Strategic Studies, 2018b) with regard to the hot spots policing, quadrants plan and problem oriented policing; it is necessary to optimize the tools to measure recent strategies implemented by the Police to face micro-trafficking, mobile phones theft or fight against criminal gangs.

With the above in mind, the question arises: How can police action effects in Colombia be measured? Certainly, the models constructed until today at international and national level have an enormous merit in the attempts to measure the capacity of Police of influencing the criminality figures; however, the challenges described in the paragraph (a) coerce to search mechanisms that allow increasing the measurements reliability. The first stage to carry out what was stated it is leaving the measurements that compare entire countries according to national indicators, and on the contrary, focusing on specific measurements, and in abandoning overviews before the intervention and after intervention favoring other more complex mechanisms. For this, the studies of the government organizations and non-government organizations (and the independent investigators or subscribed to universities) that have been appeared in Colombia are an appropriate path to diagnose the capacities of the programs to reduce criminality. In spite of it, there is still a long road to travel, so necessarily, it is required the institutional and investigative cooperation of different actors.

In this task, the quality of the statistical data generated by the National Police performs a key role in the consolidation of the reliable investigations about criminality and police activity impact. Even in a general form, statistical data provided by the institution is significant for the appropriate valuation of whole programs undertaken by the government to reduce crime.

However, to continue improving the way of obtaining the measurement of the security actions and police activity, the access to data of all the state agencies must be open (as it has been advanced), for independent investigators can participate in this labor and it becomes a way of extending the view over criminality. In this context, it is necessary the advertising of the information that does not jeopardize citizens’ personal information as a mechanism for offering to the policy makers, private sector and investigators, the elements to comprehend each territory condition and the way to approach the territorial context of coexistence and security. This situation favors the crime investigators’ work that use collected data and guarantees that the raw information provided by the police institution becomes the outcome of a team’s effort among different state agencies. Precisely, to favor this labor, in the next lines the criminality figures and the Police activity of the institution are available, looking for encouraging the permanent strengthening of the criminological investigations in the country starting from statistical inputs that the National Police keeps.

The criminality record and the police activity in Colombia in 2017

In 2017, Administrative Records of Delinquency (Registros Administrativos de Delincuencia - RAD)6 resulted in a greater record of criminality, with an increase of 11.82% over figures for the last year. The tittles of the Criminal Code that observed increased in the records were related to the economic property (44.10%), information and data protection (74.05%), crimes against animals (18.94%) and against effective and proper justice administration (16.33%). On the other hand, crimes with regard to copyright (-37.03%), against the economic and social order (-14.60%), against democratic participation (-27.78%), against public administration (-23.73%) and against legal and constitutional regime (-48.30%) showed a decrease in their records (see annexes tables 1 to 16).

Starting from the information provided above, the information was organized in the following way. First, the case of homicide during 2017 was analyzed, and some considerations about armed conflict are offered with the aim of inviting to the deepening of that analysis in subsequent investigations. Second, the crimes with greater representation in the RAD (Administrative Records of Delinquency) are shown. Those crimes are, in general, against economic property, in the next lines, those conducts with greater representation in this title are analyzed. In third place, crimes against information and data protection are shown, because they represented a greater increase in the RAD (Administrative Records of Delinquency). Fourth, crimes against administration of justice are stated, they have a sensible decrease in the RAD (Administrative Records of Delinquency). Fifth, the social impact crimes record in the capitals of the country is described. Finally, the data about the National Police operative activity during 2017 is presented.

a. Homicide in Colombia during 2017

During 2017 a decrease by 1% of the homicides recorded, from 12,402 in 2016 to 12,298 in 2017 (also, it is added a general decrease in the offences against personal integrity, because personal injuries, grew in a total from 127,212 to 132,685, representing an increase by 4%) (see annex table 5).

The explanations to understand this decrease of the homicide violence can be diverse. On one hand, the figures in 2008 belong to a period where the democratic plan security was carried out and entailed an open confrontation against insurgency. On the other hand, the recent influence of the peace process with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc), followed by the ceasefire that took place during the negotiation between the National Government and the insurgent group having an important role in the homicide violence reduction.

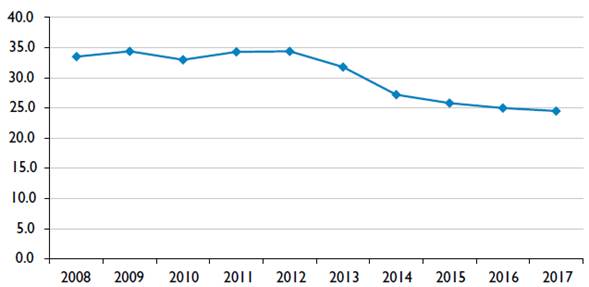

Source: Prepared by the authors based on the Siedco (2018) and DANE (2012)7.

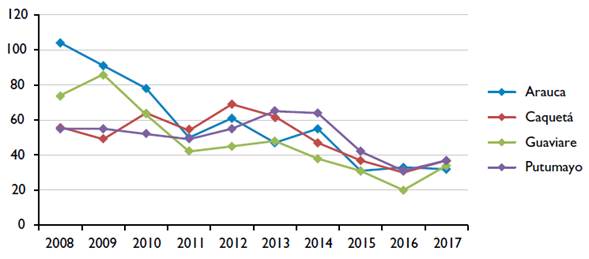

Although the incidence in the conflict is difficult to measure, the figures show a global decrease of the homicides record in the country, at the same time the conflict intensity was reduced, as an outcome of ceasefire and the definitive negotiation of peace subscribed with the Farc. A comparison of the homicide violence of the departments with greater and lesser effect of armed conflict8 seems to suggest that the armed conflict reduction has been transcendental in decreasing this type of violence. Indisputable, it seems that it is not the only explicative factor, because the homicide violence was reduced throughout the national territory. Graph 2 shows the homicide violence reduction was dramatic in the four departments with greater effect of the armed conflict. In Arauca, department with greater reduction, a decrease by 69% between 2008 and 2017 was presented, while Caquetá, Guaviare and Putumayo had a decrease of 34%, 54% and 32%, respectively.

Source: Prepared by the authors based on the Siedco (2018) and DANE (2012).

Graph 2 Homicides rate per 100,000 population in the four departments with greater effect of the armed conflict

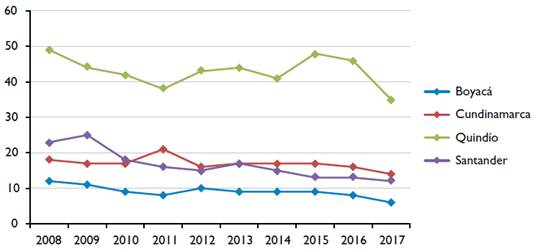

On the other hand, the departments with lower effect of the armed conflict experimented decreases, although these decreases were not as important as in places where the armed conflict grew more severe. Graph 3 shows that Boyacá experienced the most important reduction, with a decrease by 50%, while Cundinamarca, Quindío and Santander had a decrease by 22%, 29% and 38%, respectively. Although the figures are high, it is necessary to take into account that, except for Quindío, that in 2007 had a rate of 49 homicides per 100,000 population, all the other departments had lower figures of homicide violence, in this way small changes report figures with very high percentages.

Source: Produced by the authors based on Siedco (2018) and DANE (2012).

Graph 3 Rate of homicides per 100,000 population in the four departments with lower effect of the armed conflict

For example, when it is compared the reduction in the Department of Arauca, showed in graph 2, which decreases from 104 to 32 homicides per 100,000 population, with figures in Boyacá, that decrease from 12 to 6 homicides per 100,000 population, it is possible to perceive clearly the differing identity of the reported percentages in the inhabitants personal security of the inhabitants of these departments.

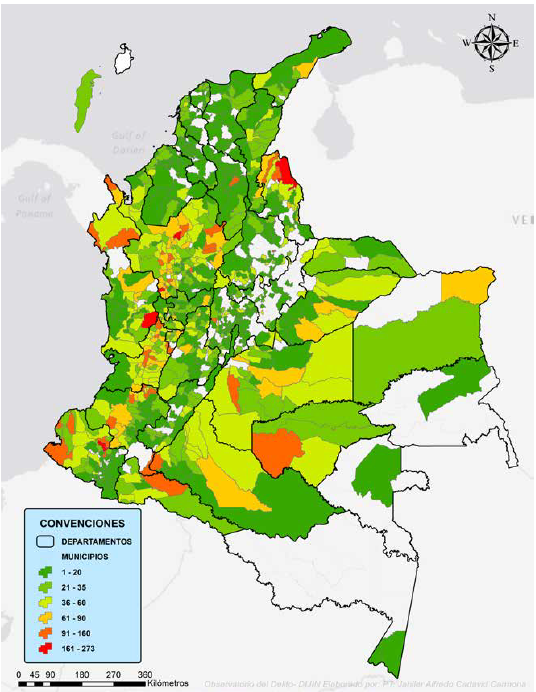

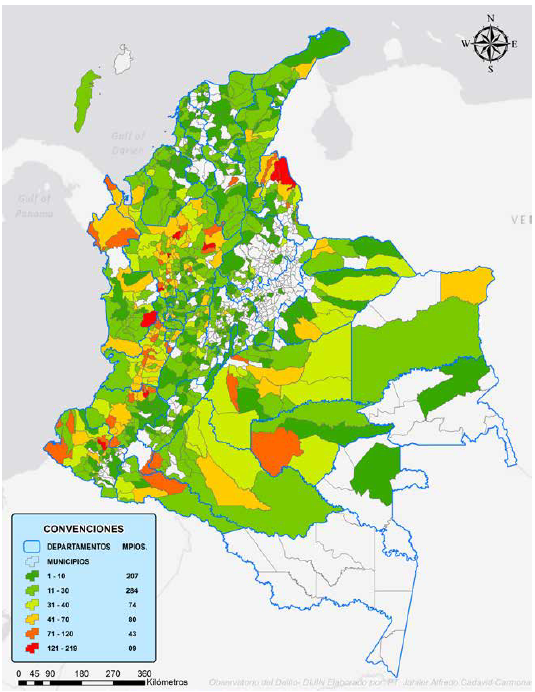

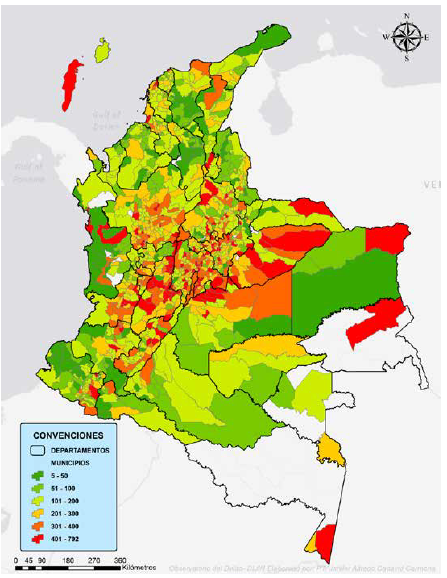

A similar outcome was obtained when it is analyzed the homicide violence in Colombia during 2017. The zones with higher rates of homicides per 100,000 population are spaces related to the great evolution of the armed conflict in the country. For instance, the Catatumbo; the access to the Pacific via Nariño department, mainly Tumaco town; Urabá area of Antioquia; the municipalities of the Darien Gulf bordering Panamá; the northeast of Antioquia; municipalities located through the Magdalena and Cauca rivers basins, and the neighboring municipalities to La Macarena highlands.

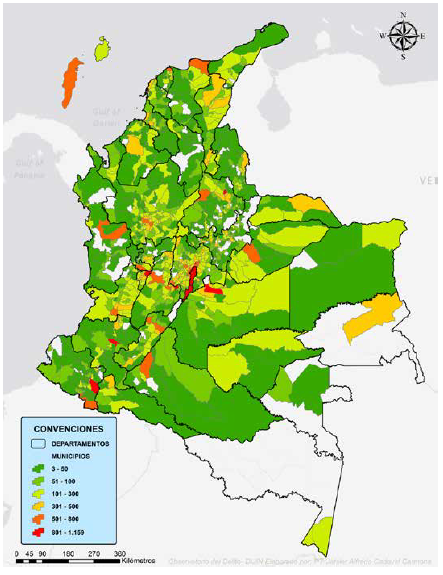

Map 1 Homicides at the national level 2017, Rate per 100,000 population

Source: Produced by the authors based on Siedco (2018); DANE (2012).

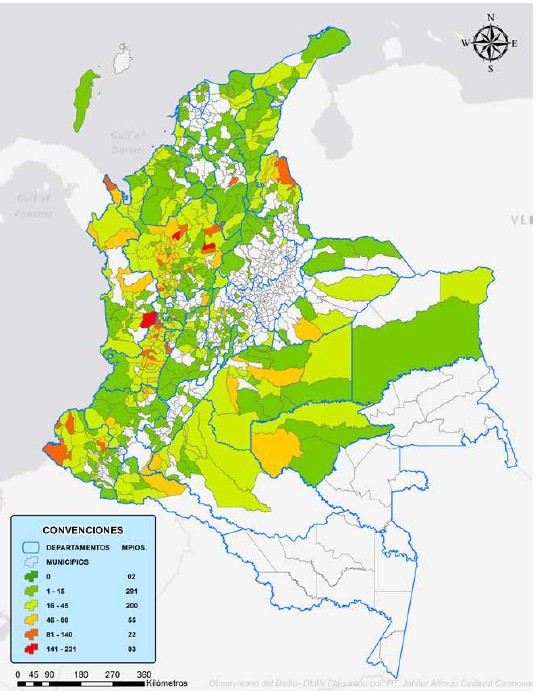

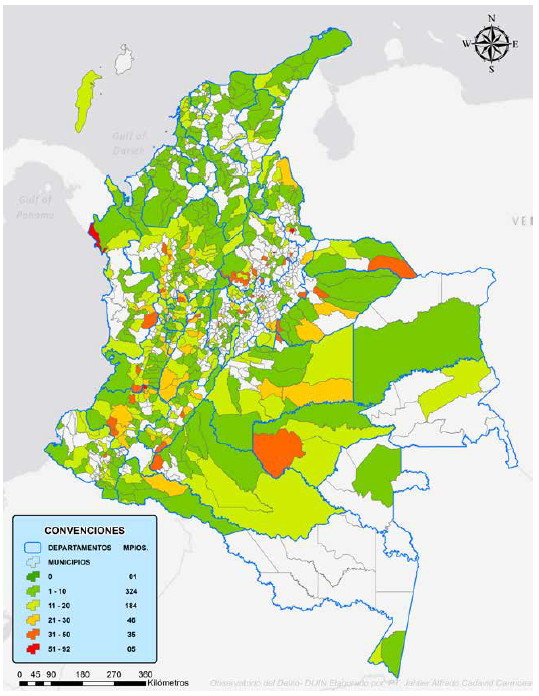

Despite the previous evidence when the homicide committing modalities in the country are analyzed, doubts arise about the armed conflict effect in some places. Although, the geographical layout of the homicides with firearms and sicariato (hired murders), modalities potentially connected to the armed conflict action and the criminal gangs operation linked to the drug-trafficking in the conflict context, seem to confirm the same zones refereed as homicide violence centers; the geographical position of the homicides perpetrated by quarrels and sharps weapons, usually related to isolated events of violence, they seem to query the relationship between homicide violence and armed conflict in some municipalities of the regions of Catatumbo and Darien Gulf and the region of La Macarena highlands. Similarly, although with smaller scope, the homicides perpetrated through these common modalities are high in some municipalities through the Magdalena and Cauca rivers basin, which problematize the conflict conception as a unique explicative factor.

Map 2 Homicides at the national level 2017, Modality of firearm, rate per 100,000 population

Source: Produced by the authors based on Siedco (2018); DANE (2012).

Map 3 Homicides at the national level, 2017 Modality of sicariato (hired murders), rate per 100,000 population

Source: Produced by the authors based on Siedco (2018); DANE (2012).

Map 4 Homicides at the national level, 2017 Modality of quarrel, rate per 100,000 population

Source: Produced by the authors based on Siedco (2018); DANE (2012).

Map 5 Homicides at the national level 2017, Modality of sharps weapons, rate per 100,000 population

Source: Produced by the authors based on Siedco (2018); DANE (2012).

This cartographic perspective to the four main modalities of homicide committing in the country, reveal that, in spite of the relationship between armed conflict and the zones with the highest rates of homicide, there are other modalities that are useful for questioning the effect of the same in the homicide violence in Colombia because they remain high in zones of conflict influence. In both cases, the institutions that emerge from this prior observation must be confirmed through specific studies of the topic.

The figures mentioned before lead to consider that the armed conflict holds an important explicative capacity, but it is necessary to look for other interpretations to understand the homicide violence reduction in the country.

b. Crimes against the economic property

The RAD (Administrative Records of Delinquency), with regard to the crimes against economic property, had an important increase in 2017 (see annex table 2); the explanation goes in two ways. The first one can be associated with the increase of these criminal modes; and the second one is described through the record capacity increase of the National Police, so even though the growth in criminality cannot be disregarded, it is possible that there is a closer approximation to what is called by the criminologists “real criminality”, too.

All the above, because the data collections systems have been improved and eased the complaints procedures of these type of conducts. This leads to the increase the number of situations that can be known by the institution, and with that, to reducing the underreport.

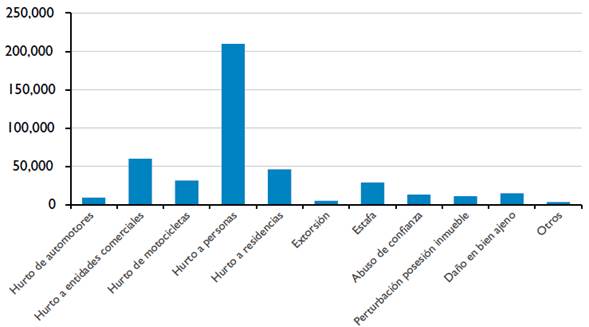

Source: Produced by authors based on the Siedco (2018).

Graph 4 Crimes against economic property, 2017

It is necessary to take into account that updating the mass media to know the information about crimes, especially to set up online applications for reporting crimes, they can have an important effect in the increase of the records capacity (Rodríguez, Romero, Caro & Campos, 2018). With this in mind, it is required to conduct studies to know the number of these crimes that obey to an expansion of crime and how many of them are the result of a higher rate of citizens’ complaints, or to an increase of the institutional capacity to detect crimes.

c. Common theft

In 2017, 316,394 common theft cases were recorded (theft affecting people, residences and commerce), of them 209,673 (66.3%) corresponding to theft affecting people, 46,497 (14.7%) to residences theft and 60,224 (19%) to commerce theft (see annex table 8).

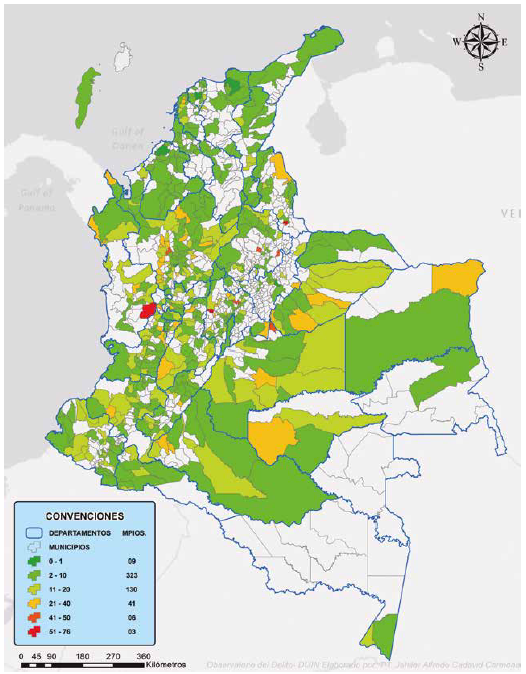

On the other hand, it is necessary to warn that most of the events took place in the capitals of the country, which represented a 71.7% of the common theft, a figure of 226,937 records. Even more, the three main cities per amount of population recorded 50% of the common theft records, with a figure of 158,137 (see annex table 16). As the following map shows, the crime with more reports (theft affecting people) only some municipalities in the country have high rates of theft per 100,000 population, lower rates of most of the municipalities in contrast with large cities is the constant.

Map 6 Theft affecting people at the national level 2017, Rate per 100,000 population

Source: Produced by the authors based on Siedco (2018); DANE (2012).

The greater increase of the RAD (Administrative Records of Delinquency) in Bogotá, showed on the map above, can be an outcome of the better information management in the capital and that has led to a reduction of the sub-report or to the rise of this modality of criminality. However, this issue must be analyzed in subsequent investigations. Also, the map shows that theft affecting people is mainly an urban phenomenon, while its presence is generally low in rural areas or with less demographic density, it helps to comprehend why Bogotá holds higher figures than other cities with smaller number of inhabitants.

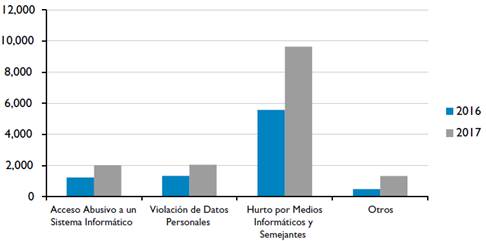

d. Crimes against information and data protection

Crimes that represented a higher percentage change in the RAD (Administrative Records of Delinquency) during 2017 with regard to the previous year, were the related ones to the information and data protection, whose rise was by 74.05% (see annex table 1). In this respect, a distinction is necessary. Crimes of this title represent a small part of the total recorded criminality of the country, with only 1.24% (see annex table 1). It involves that, in spite of the relevant figures of increase and decrease in each case, it is not in front of the main core of the country criminality; however, it is not a reason for not paying attention to both situations.

Although, the crimes of the title increased their record with regard to the last year, those crimes that stand out because of the number of reported cases are those ones of abusive access to a computer system, that augmented from 1,239 to 2,019 cases, and that represented an increase by 63%; violation of personal information increased from 1,346 to 2,055 cases, with a rise by 52.7%, and the theft by using computer means and similar, that increased from 5,570 to 9,638 cases, and it represented a growth by 73%. The possible explanations to the previous increases are connected to the information technologies expansion, the greatest permeation to the connectivity services provision, the increase of the use of online applications and electronic card payment systems and the greatest capacity of detection of behaviors connected to this title of the Criminal Code (see annex table 2).

Source: Produced by the authors based on Siedco (2018); (Norza, Peñalosa & Rodríguez, 2016).

Graph 5 Crimes against protection of the information and data in Colombia in 2016 and 2017

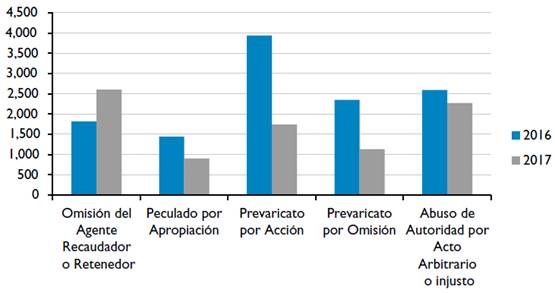

e. Crimes against public administration

According to figures in 2016 and 2017, the crimes stated on that title of the Criminal Code varied from 25,018 reports to 19,082, which implies a decrease of the RAD by 23.73% (see annex table 1). In the title, integrated by almost 40 crimes, the behavior was different according to the concrete criminal type. Nevertheless, the crimes with greater representation experienced positive changes, except for omission or the failure to report of the withholding agent or collector, it increased from 1,816 to 2,605 cases, with a rise by 43.4% (see annex table 2). This situation draws the attention, since it is a crime of tax evasion that can only be committed by legally constituted enterprises, which must withhold taxes on the behalf of the State.

On the other hand, the four crimes with greatest representation in the tittle showed a decrease in the RAD. The peculation due to unlawful appropriation fell from 1,446 to 905 reports, it decreased by 37.4%; prevarication through action declined from 3,941 to 1,741 reports, with a decrease by 55.8%; prevarication through omission or failure to report dropped from 2,350 to 1,135 reports, decreased by 51.7%, and the abuse of authority by either arbitrary or unjust act diminished from 2,595 to 2,271 reports, for a decrease of 12.4% (see annex table 2).

Source: Produced by the authors based on Siedco (2018); (Norza, Peñalosa & Rodríguez, 2016).

Graph 6 Main crimes against public administration in Colombia in 2016 and 2017

f. Crimes of social impact

Crimes of impact are treated in the RAD starting from a convention to determine the representative conducts that are part of this category. In this sense, crimes considered of impact are: the homicide, abduction, coercion, terrorism, subversive activities, people dead under public forces’ procedures (army or police), personal injuries; common theft (theft affecting people, residences and commerce), vehicles theft, livestock theft, financing entities theft, land piracy, injuries in traffic accidents and homicides in traffic accidents (see annex table 4). These crimes are divided in three categories, which are analyzed in the next lines.

Initially, the crimes that affect public security are indicated, comprising crimes related to homicide, abduction, terrorism, subversive actions and the people dead under the public forces’ procedures. About this category, the RAD had similar records between 2016 and 2017, with 17,483 records in 2016 and 17,897 in 2017. Secondly, there are crimes of impact that affect the citizenship security, involving injuries, different forms of theft and land piracy. In this case, the RAD reported a growth by 36%, increased from 364,184 records to 496,488. It mainly deals with the increase of the record of theft that was analyzed on the paragraph (c) of this subheading. Thirdly, there are crimes of impact that affect traffic and road security, homicides and injuries in traffic accidents are included here, which reduced their records declining from 67,192 to 59,644 records in the RAD (see annex table 4).

In the capitals of the country, the crimes of social impact with a greater record were related to economic property, already analyzed, and the personal injuries and homicide. As illustrated previously, common theft is focused in the main cities of the country, especially in Bogotá, Medellin and Cali (see annex table 16). About homicide and injuries, these cities are leading the total of the figures, something evident, if it is taken into account that they hold more population than other cities. Notwithstanding, in both categories the rates of these crimes are inferior in those cities when are compared to other territory places. The homicides rate map by municipalities is included in the paragraph to sustain above statements. Following this, it is encompassed the personal injuries map per 100,000 population for all the municipalities, it can be verified on this map that those cities have lower rates than other municipalities of the country.

Map 7 Personal injuries at the national level 2017, Rateper 100,000 population

Source: Produced by the authors based on Siedco (2018); DANE (2012).

In sum, some components of the criminality records have been described that indicate their variations. However, in this article a greater number of data is incorporated, which is framed in tables discriminating the territoriality in Colombia in 2017, allowing identifying the criminal dynamics in the country and, with this, to obtain relevant inputs to diagnosing the criticality of the regions and priorities in security and coexistence topics.

g. Records of the police activity in 2017

This part of the text is divided in two parts, in first place, it is stated the police activity related to arrests and, in second place the related one to the seizures and recoveries.

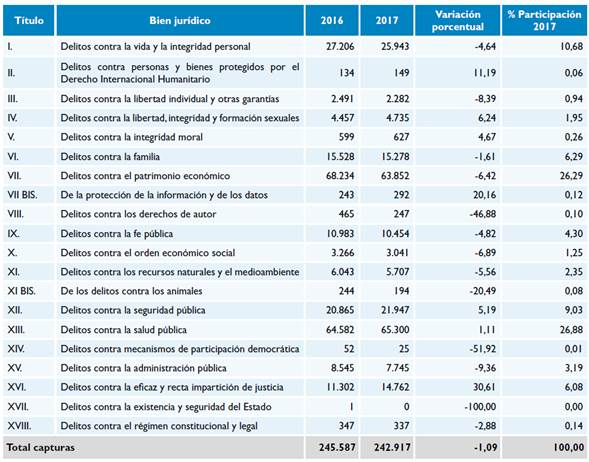

In 2017, 242,917 arrests were carried out, 1.09% less than in the last year (see table annex 19). The tittles with greater representation in the total of the arrests were related to life and personal integrity (10.68% of the total), economic property (26.29% of the total) and the crimes against public health (26.88% of the total). Only in three titles a decrease was presented in the amount of arrests. But, at having these crimes a negligible participation in the total of crimes in the country, any modification in the arrests represents figures that, despite they provide high percentages, they do not evidence drastic changes in the security of the country or in the police activity. This is the case of the crimes against copyright, against democratic participation and against constitutional and legal regime that show a decrease in the rates of arrest by 46.88%, 51.92% and 100%, respectively, but the reports of arrests in the last year were scarcely 465, 52 and 1 individual arrested.

Table 1 Comparative of arrests by title of the Criminal Code in Colombia in 2016 and 2017

Source: Produced by the authors based on the Siedco (2018).

The four departments, and the capital, with greater amount of captures were: Antioquia, Bogotá D. C., Santander, Valle and Cundinamarca, where 45,170, 38,148 16,764, 16,601 and 12,422 were recorded, respectively (see annex table 23). The focus of the arrests in Antioquia, Bogotá, Valle and Cundinamarca is not a surprise, because they are the departments with a higher number of inhabitants. However, the presence of the department of Santander draws attention, thus why Atlántico and Bolívar have a higher number of population.

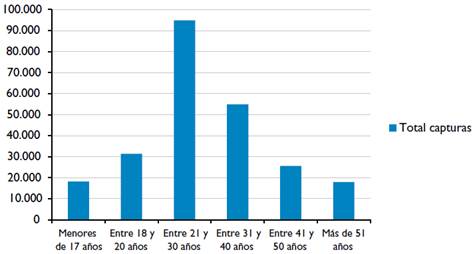

Concerning with the sex of the arrested people, they have been mainly men, who represent a 88.65% of the total of the arrests, and women 11.35% (see annex table 24). It is important to stress that the RAD is working with this binary form of measuring arrests, consequently the existence of persons with identities of unlike genre may not be differentiated. Detained people average age is between 21 and 30 years, who represent 22.60% of the total of the arrests.

Source: Produced by the authors based on the Siedco (2018); DANE (2012).

Graph 7 Amount of arrests by age average in 2017

With regard to the seizures in 2017, 789,262.48 kilograms of narcotics were seized, becoming the higher amounts related to the cocaine (320,050.58 kilograms), marijuana (190,538.92 kilos), coca leaf (177,262.74 kilograms) and hallucinogenic tablets (60,137 tablets) (see annex table 37). In addition, a total of 23,865 firearms were seized, becoming the higher numbers related to revolvers (9,443), handguns (4,975) and shotguns (8,638) (see annex table 34). Concerning with the stated above, 354,446 ammunition items were seized; too, 230,437 of them were for rifle type weapons, it was the highest confiscation of these type of weapons (vid. annex table 35).

About the recoveries, in 2017, 11,803 motorcycles were recovered, for a value greater than 53 thousand millions pesos (see annex table 29). In addition, a total of 3,828 vehicles were recovered, for a cost higher than 185 thousand million pesos (see table annex 28). Moreover, 329,985 goods were recovered, such as animals, motor parts, money, household appliances and computer equipment, among others.

Finally, in this descriptive line of the Police performance against crime, it is emphasized, according to the implementation of the Criminal Code of the National Police in 2017 (see annex table 18), the record of 399,584 contrary behaviors to the coexistence in the national territory, 147,582 of them were related to opposing behaviors to the care and integrity of the public space.

Hence, just like it was mentioned in the criminality description, more tables are added, they compile data of the operational activity of the National Police and provide the reader with a variety of data to the crime and security analysis. As it has been stated, the objective of this article is to show data for understanding the criminogenic dynamics and contributing to the different investigations developed in the country on the crime issue.

Conclusions

The recent decrease of the homicide in Colombia becomes a success in terms of reducing violence. Although, the figures are still high, in the last ten years the homicides rate fell almost by 27%, decreased from 33,5 homicides per 100 thousand population in 2008, to 24,5 in 2017 (graph 1). In 2017, there was a reduction by 1% of the recorded homicides, dropped from 12,402 in 2016 to 12,298 in 2017 (also, it is added, a general reduction of the records in violence against personal integrity, thus why personal injuries changed from a total of 127,212 to 132,685, which shows an increase of 4%) (see annex table 5).

On the other hand, common theft reality is difficult to diagnose. Although, the RAD (Administrative Records of Delinquency) provides an increase in the records, it is not possible to know if the rise is because of the increase in the criminality or due to the greater capacity of the RAD to identify cases in this matter. The focus in the common theft in the main cities per number of population shows that this is mainly an urban issue, although it is not exclusive.

The crimes that represented a greater percentage deviation in the RAD in 2017 were related to information and data protection, which increased by 74.05%. In this case, the increase in the institutional capacity to detect criminal acts seems a plausible explanation, because it is still an unknown category for the criminological investigation. Nevertheless, it is not possible to arrive to absolute conclusions. In any case, crimes of this title represent a small figure of the total of criminality.

With regard to the crimes against public administration, the RAD reported a decrease in the records, except for the case of omission or failure to report of a withholding or collector agent, in this case there was an increase by 43.4%. In the other four crimes with greater representation in the title, there were reductions. The peculation due to unlawful appropriation reported a decrease by 37.4%; prevarication through action by 55.8%; prevarication through omission by 51.7%, and the abuse of authority by either arbitrary or unjust act by 12.5%. Concerning with the crimes of high social impact, except for theft cases, the RAD had similar records between 2016 and 2017. In this case, the considerations operate in the same way with regard to the rise in the theft record.

The information presented opens diverse ways of analysis to determining the reasons of the reduction or increase in those figures (or others that can be consulted in the annexes of this article), and to trying to investigate in an increasing and deeper way different factors that can have impact in the behavior of them. Precisely, the objective of the discussion that is stated at the beginning is an invitation to use the figures provided to conduct more studies engaged in crime from different approaches.

REFERENCES

Alcaldía Mayor de Bogotá (2018). Aclaración sobre las implicaciones de los cambios metodológicos introducidos por la Policía Nacional y la Fiscalía General de la Nación en las cifras de criminalidad en Bogotá. Bogotá: Alcaldía Mayor de Bogotá. [ Links ]

Bauman, Zygmunt (2015). Modernidad líquida. Madrid: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Bayley, D. (1994) Police for the future. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Beltrán, Isaac de León & Salcedo Albarán, Eduardo (2014). El crimen como oficio: ensayos sobre economía del crimen en Colombia. Bogotá: Ediciones de la U. [ Links ]

Blattman, C., Green, D., Ortega, D. & Tobón, S. (2017). Pushing Crime Around the Corner? Estimating Experimental Impacts of Large-Scale Security Interventions. NBER Working Paper Series, 23941: 1-29. [ Links ]

Braga, A. A., Weisburg, D., Waring, E., Mazerolle, L. G., Spelman, W. & Gajewsky, F. (1999). Problem-oriented policing in violent crime places: a randomized controlled experiment. Criminology, 37 (3): 541-580. [ Links ]

Braga, A. A., Papachristos, A. V. & Hureau, D. M. (2001). “The effects of hot spots policing on crime”. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science (578). [ Links ]

Braga, A. A., Papachristos, A. V. & Hureau, D. M. (2014). The effects of hot spots policing on crime: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Justice Quarterly, 31 (4): 633-663. [ Links ]

Braga, A. A. (2005). Hot spots policing and crime prevention: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 1 (3): 317-342. [ Links ]

Braga, A. A. & Bond, B. (2008). Policing crime and disorder hot spots: a randomized controlled trial. Criminology, 46 (3): 577-607. [ Links ]

Braga, A. A., Papachristos, A. V. & Hureau, D. M. (2013). Deterring gan-involved gun violence: measuring the impact of Boston’s Operation ceasefire on street gang behavior. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 30 (1): 113-139. [ Links ]

Braga, A. A., Weisburg, D. & Turchan, B. (2018). Focused deterrence strategies and crime control. American Society of Criminology, 17 (1): 205-250. [ Links ]

Bulla, Patricia & Ramírez, Boris (2016). Los puntos calientes requieren intervenciones integrales: la acción policial no basta. Bogotá: FIP. [ Links ]

Bulla, Patricia; García, Juan Felipe; Lovera, María Paula, & Wiesner, Daniel (2016). Homicidios y venta de drogas: una peligrosa combinación. Bogotá: FIP. [ Links ]

Chalfin, Aaron & McCrary, Justin (2012). The effect of police on crime: new evidence form U.S. cities, 1960-2010. NBER Working Paper, 18815. [ Links ]

DANE (2011). Estimaciones de población 1985-2005 y proyecciones de población 2005-2020 total departamental por área. Recuperado de: www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/demografia-y-poblacion/proyecciones-de-poblacion [ Links ]

DANE (2012). Colombia. Necesidades Básicas Insatisfechas (NBI), por total, cabecera y resto, según municipio y nacional. Recuperado de: https://www.dane.gov.co/files/censos/resultados/NBI_total_municipios_30_Jun_2012.xls [ Links ]

De Vicente Martínez, Rosario (2006). El principio de legalidad. Valencia: Tirant lo Blanch. [ Links ]

Deadman, Derek & McDonald, Ziggy (2002). Why has crime fallen? An economic perspective. Oxford: Institute of Economic Affairs. [ Links ]

Departamento Nacional de Planeación (2016). Índice de incidencia del conflicto armado. Bogotá: DNP. [ Links ]

Durkheim, Emile (1969). Two laws of penal evolution. Cincinnati Law Review, 32. [ Links ]

Eck, J. & Maguire, E. (2000). Have changes in policing reduce violent crime? An assessment of the evidence. En: A. Blumstein & J. Wallman (Eds.). The crime drop in America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Ehrlich, I. (1973) Participation in illegitimate activities: a theoretical and empirical investigation. The Journal of Political Economy, 81 (3): 521-565. [ Links ]

Escobedo, Adolfo; Ramírez, Boris, & Sarmiento, Paula (2017). Bogotá sin el Bronx: expendios y habitantes de la calle. Bogotá: FIP. [ Links ]

Ferrajoli, Luigi (2011). Derecho y razón: teoría del garantismo penal (trad. Perfecto Andrés Ibáñez, Alfonso Ruiz-Miguel, Juan Carlos Bayón Mohino, Juan Terradillos Basoco & Rocío Cantareno Bandrés). Madrid: Trotta. [ Links ]

Fundación Ideas para la Paz (2012). Evaluación de impacto del Plan Nacional de Vigilancia Comunitaria por Cuadrantes. Bogotá: FIP. [ Links ]

Fundación Ideas para la Paz, Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo y Policía Nacional (2014). La planeación focalizada y el trabajo coordinado reducen el crimen: evidencias en ciudades colombianas . Agosto 2014. Bogotá: FIP-BID-Policía Nacional. [ Links ]

Garland, David (2005). La cultura del control. Barcelona: Gedisa. [ Links ]

Gatrell, V. A. C. (1980). The decline of theft and violence in Victorian and Edwardian England. En: V. A. C. Gatrell, B. Lenman & G. Parker (Eds.). Crime and the law: the social history of crime in Western Europe since 1500. London: Europa Publications. [ Links ]

Gómez, S., Mejía, D. & Tobón, S. (2017). The Deterrent Effect of Public Surveillance Cameras on Crime. Documentos CEDE, 9: 1-26. [ Links ]

De Folter, R. S., Steinert, H., Scheerer, S., Mathiesen, T., Christie, N. & Hulsman, L. H. C. (1989). ¿Qué significa el no cuestionamiento (ni rechazo) del concepto de delito? En: M. A. Ciafardini & M. L. Bondanza (Trads.). Abolicionismo penal. Buenos Aires: Ediar. [ Links ]

La Rota Uprimny, Miguel Emilio & Bernal Uribe, Carolina (2013). Seguridad, policía y desigualdad: encuesta ciudadana en Bogotá, Cali y Medellín. Bogotá: Centro de Estudios de Derecho, Justicia y Sociedad, DeJusticia. [ Links ]

Levitt, Steven D. (1995). Why do increases arrest rates appear to reduce crime: deterrence, incapacitation, or measurement error? Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research-Working Paper 5268. [ Links ]

Levitt, Steven D. (1998). Why do increases arrest rates appear to reduce crime: deterrence, incapacitation, or measurement error? Economic Inquiry, 36 (3): 356-372. [ Links ]

Levitt, Steven D. (2002). Using electoral cycles in police hiring to estimate the effect of police on crime: reply. American Economic Review, 87 (3): 270-290. [ Links ]

Liedka, Raymond V., Piehl, Anne Morrison & Useem, Bert (2006). The crime-control effect of incarceration: does the scale matter? Criminology and Public Policy, 5 (2): 245-276. [ Links ]

Lindström, Peter (2013). More police-Less crime? The relationship between police levels and residential burglary in Sweden. The Police Journal, 86 (4): 321-339. [ Links ]

Marvell, T. B. & Moody, C. E. (1996). Specification problems, police levels, and crime rates. Criminology, 34 (4): 609-646. [ Links ]

Mejía, Daniel & Restrepo, Pascual (2016). Crime and conspicuous consumption. Journal of Public Economics 135: 1-14. [ Links ]

Mejía, Daniel; Ortega, Daniel, & Ortiz, Karen (2014). Un análisis de la criminalidad urbana en Colombia. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes. [ Links ]

Mejía, Daniel; Restrepo, Pascual, & Rozo, Sandra V. (2017). “On the effects of enforcement on illegal markets: evidence from a quasi-experiment in Colombia”. The World Bank Review, 31 (2): 570-594. [ Links ]

Mitchell, Don (2014). The right to the city: social justice and the fight for public space. New York-London: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Norza Céspedes, Ervyn (2017). Evidence-based policing (E.B.P.): criminología en la Policía Nacional de Colombia. En: F. Benavides Vanegas (Ed.). Criminología en Colombia (pp. 306-346). Bogotá: Grupo Editorial Ibáñez. [ Links ]

Norza Céspedes, Ervyn; Peñalosa Otero, María Jimena, & Rodríguez Ortega, Jair David (2016). Exégesis de los registros de criminalidad y actividad operativa de la Policía Nacional. Revista Criminalidad, 59 (3): 9-40. [ Links ]

Oficina de Análisis de Información y Estudios Estratégicos (2016). Boletín mensual de indicadores de seguridad y convivencia . Bogotá, 2016. Bogotá: Alcaldía Mayor de Bogotá. [ Links ]

Oficina de Análisis de Información y Estudios Estratégicos (2018a). Boletín mensual de indicadores de seguridad y convivencia. Diciembre 2017. Bogotá: Alcaldía Mayor de Bogotá. [ Links ]

Oficina de Análisis de Información y Estudios Estratégicos (2018b). Boletín mensual de indicadores de seguridad y convivencia . Febrero 2018. Bogotá: Alcaldía Mayor de Bogotá. [ Links ]

Papachristos, Andrew V. & Kirk, David S. (2015). Changing the street dynamic. Criminology & Public Policy, 14 (3): 525-558. [ Links ]

Pare, Paul Philippe (2014). Indicators of police performance and their relationship with homicide rates across 77 nations. International Criminal Justice Review, 24 (3): 254-270. [ Links ]

Parra Domínguez, Javier; García Sánchez, Isabel María, & Rodríguez Domínguez, Luis (2013). Relationship between police efficiency and crime rate: a worldwide approach. European Journal of Law and Economics, 39 (1): 203-223. [ Links ]

Philips, D. (1977). Crime and authority in Victorian England: the black country, 1835-1860. London: Croom held. [ Links ]

Policía Nacional (2012). Modelo Nacional de Vigilancia Comunitaria por Cuadrantes (MNVCC). Bogotá: Policía Nacional. [ Links ]

Raphael, Steven (2014). How we reduce incarceration rates while maintaining public safety. Criminology & Public Policy, 13 (4): 579-597. [ Links ]

Rodríguez Ortega, Jair David; Romero Hernández, Mauricio; Caro Zambrano, Lorena del Pilar, & Campos Méndez, Franney (2018). Proceso de integración de registros administrativos de criminalidad entre la Fiscalía General de la Nación y la Policía Nacional de Colombia. Revista Criminalidad (en imprenta). [ Links ]

Rusche, Georg & Kirchheimer, Otto (1984). Pena y estructura social. Bogotá: Temis. [ Links ]

Sánchez, Fabio & Moreno, Álvaro José (2007). La recuperación del espacio público y su impacto en el crimen: el caso de TransMilenio. En: F. Sánchez (Ed.). Las cuentas de la violencia. Bogotá: Norma. [ Links ]

Sánchez, Fabio; Espinosa, Silvia, & Rivas, Ángela (2007). ¿Garrote o zanahoria?: factores asociados a la disminución de la violencia homicida y el crimen en Bogotá. En: F. Sánchez (Ed.). Las cuentas de la violencia. Bogotá: Norma. [ Links ]

Siedco (2018). Estadística delictiva. Homicidios 2017. Recuperado de: https://www.policia.gov.co/grupo-informaci%C3%B3n-criminalidad/estadistica-delictiva [ Links ]

Silva Sánchez, Jesús María (2001). La expansión del derecho penal: Aspectos de la política criminal en las sociedades postindustriales. Madrid: Civitas [ Links ]

Simon, Jonathan (2011). Gobernar a través del delito (trad. Victoria de los Ángeles Boschiroli). Barcelona: Gedisa. [ Links ]

Steen, Sara & Bandy, Rachel (2007). When the policy becomes the problem. Criminal justices in the new millennium. Punishment & Society, 9 (1): 5-26. [ Links ]

Sotomayor Acosta, J. O. & Tamayo Arboleda, F. L. (2014). La “nueva cuestión penal” y los retos de una ciencia penal garantista. En: Dogmática del Derecho Penal y Procesal y política criminal contemporáneas. LH. Bern Shünemann. Lima: Gaceta Penal. [ Links ]

Tonry, Michael (2011). Punishing race: a continuing American dilemma. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Velásquez, Fernando (2013). Manual de Derecho Penal: parte general. Bogotá: Ediciones Jurídicas Andrés Morales. [ Links ]

Wacquant, Löiq (2012). Castigar a los pobres: el gobierno neoliberal de la seguridad social. Barcelona: Gedisa. [ Links ]

Weisburg, David & Eck, John E. (2004). What can Police do to reduce crime, disorder and fear? The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 593 (1): 42-65. [ Links ]

Williams, D. J., Linden, W., Currie, D. & Donelly, P. D. (2014). Adressing gang-related violence in Glasgow: A preliminary pragmatic quasi-experimental evaluation of the community initiative to reduce violence (CIRV). Aggression and Violent Behaviour, 19 (6): 686-691. [ Links ]

Young, Jock (2003). La sociedad excluyente: exclusión social, delito y diferencia en la modernidad tardía. Barcelona: Marcial Pons. [ Links ]

1Additionally, this article presents different tables as annexes with statistics of criminality and the police activity in Colombia during 2017.

2La Policía no previene el crimen. Este es uno de los secretos mejor guardados de la vida moderna. Los expertos lo saben, la Policía lo sabe, pero el público no lo sabe. Aun así, la Policía afirma ser la primera defensa de la sociedad contra el crimen, y continuamente argumenta que si ellos reciben más recursos, especialmente en lo que a personal se refiere, serán capaces de proteger a la comunidad frente al crimen. Esto es un mito (free translation by the authors).

3This law allows to impose more severe sentences to individuals who had been condemned for violent crimes or other serious crimes.

4The pulling levers operations are focused forms of intervention for approaching the violent and organized criminality, in which risk factors are initially determined and subjects are subjugated to them for carrying out interventions of different types (police, social or community). The use of this strategy started in 90s in Boston with the ceasefire operation and later it was taken to other cities in United States (Braga, Weisburg and Turchan, 2018).

5In this case, Police met with the gangs members to ask an unconditional ceasefire. There was not any kind of negotiation but there was not any repression (Papachristos and Kirk, 2015).

6In this part of the text, it has been decided to use the term Registros Administrativos sobre la Delincuencia (Administrative Records of Delinquency) (RAD), instead of referring to criminality figures. It is because, according to what is shown in the first part, it is identified the complexity that there is in documenting in an appropriate way the criminal phenomena. Thus, it is better to speak about crimes that are reported to the statistics staff of the National Police. It allows taking away the problem of the “off-the-record” or “dark figures of crime” and avoiding the problem of sub-report that, although it is an important topic for measuring the impact of different strategies for controlling crime, it does not have any relevance when statistical records of cases reported to the institution are submitted. In this case, and as it was mentioned throughout the text, it is necessary to take into account that the integration of the statistic system of the National Police and the Office of the Attorney General of the Country, as well as the implementation of the mobile applications for reporting crimes seem to have increased the capacity of recording crime.

7It is important to add data of population with DANE projections (National Administrative Department of Statistics), calculated through the data collected in the census of 2005.

8The index prepared by Departamento Nacional de Planeación (2016) (National Department of Planning) was used to decide the departments with less incidence of the armed conflict.

Received: January 12, 2018; Revised: April 18, 2018; Accepted: May 21, 2018

texto em

texto em