Introduction

Homicides in Cali and Colombia has been attributed to multiple factors, including the presence of organized crime, drug trafficking, interpersonal violence and the presence of street gangs (Fandino-Losada et al., 2017). Particularly, street gangs are known to participate in micro-traffic of drugs and robberies in Cali's neighborhoods (CCV, 2015; Fandino-Losada et al., 2017), and 34% of all homicides in 2015 in Cali are attributed to street gang violence (OSC, 2016) Cali a city with 2.228.000 inhabitants (DANE 2018) is one of the cities in Colombia and Latin America with the highest rate of homicides, with a rate of 48 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2018. Although the rate of homicides has been much lower in recent years compared to what it was in the nineties, Cali continues to be in the list of the most violent cities in the world (CCSPJP, 2017). According to the Metropolitan police (personal communication), by 2016 there were 106 known street gangs in Santiago de Cali.

Street gangs are an important challenge for cities worldwide, not only because of delinquency rates but also due to the social cost that having adolescents and young adults participating in these groups. Nevertheless, for many adolescents in context of disadvantage, the street gang is a source of support and protection, especially given the lack of family networks and support. The Eurostreet gang program defines a street gang as "any durable, street-oriented youth group whose involvement in illegal activity is part of its group identity" (Klein and Maxson, 2006).This definition encompasses the young profile of street gang members, while it describes the durable aspect of these groups, founded in the strong cohesion among its members.This cohesion and sense of belonging provides multiple elements to street gang members (e.g., empowerment and support), and these characteristics of street gangs can potentially be promoted in alternative directions, other than illegal activity, to enhance personal growth and well being (Klein and Maxson, 2006).

The risk factor approach to street gang involvement, suggests that there are different risk factors for youth that can be grouped in 5 domains: individual, family, school, peer group, and community (Howell and Egley, 2005). Those who join a street gang usually have multiple risk factors from each of these domains (Howell and Egley, 2005). Structural factors at the neighborhood and family level can influence the risk of street gang membership through attenuation of social bonds (Thornberry et al., 2003). In turn, the weakening of social bonds can elevate the risk of antisocial attitudes and beliefs, with criminal behavior being triggered by feelings of injustice, racial and poverty narratives. Street gangs can offer protection, excitement and increased social bond and other perceived social benefits to disenfranchised youth with weak social bonds. The risk factor approach indicates that intervention programs are needed to reduce risk factors and rehabilitate individuals involved in delinquent activities and to separate street gang-involved youth from these gangs (Thornberry et al., 2003). However, alternatively, interventions could also work with the street gang as a whole to move it in more pro-social directions, away from illegal activity, and using the interconnection and social bonds of street gangs to promote and strengthen its members' capacities.

Deterrence interventions aim to change the behavior of individuals through the strategic application of enforcement and social service resources to facilitate desirable behaviors (Braga et al., 2018). They usually involve forming an enforcement group conformed by different agencies including the local police, probation, parole, state and federal prosecutors, and federal law enforcement agencies. Focused deterrence interventions can also include alternative approaches aiming at improving the life of street gang members through job training, employment, substance abuse treatment, housing assistance, and a variety of other services and opportunities (e.g., the Cure Violence model in the United States) (Braga et al., 2018). These alternative approaches, do not involve the use of force or the threat of punishment, but focus on teaching individuals new forms of conflict resolution while"denormalizing" the harmful behavior, through 1) interrupting transmission of violence; 2) identifying and changing the thinking of potential transmitters; and 3) changing group norms regarding violence (Butts et al., 2015). In this model, previous street gang members who have changed their lives may work as violence interrupters, i.e. they persuade youth that there are other ways to negotiate the conflict without engaging in more violence. By sharing their experiences, interrupters challenge the norms and narratives used as excuses to commit violent acts, and promoting improved ways of living. This approach also uses outreach workers who connect high-risk individuals to resources in the community, including employment, housing, recreational activities, and education (Butts et al., 2015).

Following the experience from other cities in the world, in 2016 the Mayor's office from Santiago the Cali, Colombia, the chief's office of the Police department, and the Cisalva institute worked together on a project, "TIP -Youth without frontiers", with the goal to reduce street gang-related violence in Cali's communes. Different street gangs were contacted and invited to participate in the project. The "TIP -Youth without frontiers" intervention attempts to change youth violent behavior in youth in a way similar to public health approaches designed to reduce the impact of harmful behavior, such as smoking or binge drinking. Similar to the strategy used in the cure violence model (Butts et al., 2015), the intervention identifies individuals at risk (i.e., street gang members) who are invited to participate as a group in activities that offer different elements to grow and to develop personal skills. Given that interventions that attempt to address risk factors from multiple domains are the ones most likely to be successful (Higginson et al., 2015; Klein and Maxson, 2006; O'Brien et al., 2013), this intervention focuses on six components that attempt to work on youth's emotional skills (e.g., self-control and well-being), connect youth employment and educational opportunities and access to health and other public services, while providing spaces for recreation. The program also focuses on enhancing family and social participation and sense of belonging, which can eventually produce changes in youth's believes, attitudes and behavior. The program activities also help participants to get well connected with their neighbors, to build new networks and to find their way back in society. This intervention also promotes social inclusion and the restitution of citizen rights to street gang members. In addition, the intervention can set the ground for public policies providing services to youth at disadvantage.

In this paper, we describe the methodology of this intervention, which aimed to reduce violent behavior among street gang members, and its implementation between 2016-18. Because of the intervention's focus on reducing violence in neighborhoods where street gangs are influential, we also examined whether or not this intervention was associated with a reduction in homicides in these communes between 2015-18.

Description of the "TIP -Youth without frontiers" intervention

"TIP -Youth without frontiers" was supported by the Security and Justice Secretary from the Mayor's office from Santiago de Cali, with funds that were provided through the Municipal development plan from Santiago de Cali 2016-2019, Cali progresses with you ("Cali Progresa Contigo"). The Cisalva Institute, from Universidad del Valle, is the institution executing this project in collaboration with the National Police (Preventive Police Unit, TIP - Gang integral treatment program). The Cisalva Institute and the National Police discuss activities and make all final operational decisions by reaching consensus on these activities. The municipal police department reported there to be a total of 106 street gangs and 1.580 street gang members in Cali in 2014. A total of 84 street gangs have participated of the 'TIP-Youth without frontiers" intervention (2,107 youth entering the program). To date, there are 64 active groups participating in the program.

Street gang definition:

The street gang definition used in this intervention was any group of three or more members, who are between 12 and 28 years old, which has formed spontaneously by affinities of interests, spatial closeness, consanguinity and friendship, and that seeks social recognition denied in childhood (family and/or school). This definition was used as the assessment criteria as to whether an individual was entered into the program. The group settles in a focused area of their community, which they defend as their personal space, usually involving violent confrontations with similar groups. However, a street gang is not a criminal band; they may have committed some felonies, e.g., robberies or even homicides as a result of confrontations with other street gangs, but they have not been paid or sponsored to commit these acts.

The six components of the intervention: The TIP program is based on the integral services model approach, which comprises six components that are interrelated, and a transversal component focusing on prioritized communes (by 2018 eight communes had been prioritized). The six components are: 1) characterization, monitoring, follow up and evaluation, 2) psychosocial, drug use intervention and self-care, 3) leadership, job-seeking and performing skills, employment and entrepreneurship training; 4) education to finish secondary school, and to improve access to technical and university training; 5) engagement in sports and recreational activities that improve social cohesion; 6) restitution of citizen rights to youth at disadvantage. Besides these components, the program also focuses on skills to build family cohesion and facilitate social-reparation-activities to neighbors who had been affected by deleterious street gang activities in the past.

The six components are described briefly: 1)The first component "characterization, monitoring, follow up and evaluation" is the official first approach to the group. The groups are exposed to the program goals and characteristics. After at least three pre-encounters with the program staff, street gang members are invited to become part of the program by signing an agreement to no commit anymore felonies and to engage in a process to leave behind their violent behavior. After participants sign the agreement, they are invited to a full-day gathering at a green open space, where they meet other participants and program staff. During this day participants go through three main activities: First, they participate in icebreaker activities. Second, life-plan sheets are provided to each participant in which they can describe their life short- and medium-term goals for a better future, and the potential barriers they believe can prevent them from reaching their goals and from accessing the city's public services. Third, each participant is surveyed with an instrument that includes questions on socio-demographic, education, employment, alcohol/drug use, their group of friends and family characteristics. The information provided in the survey will serve as the baseline to analyze the impact of the intervention. This component also involves activities to follow up and monitor participants, and to evaluate the intervention. During the monitoring and evaluation parts of the component, operating units (described below) conduct monthly follow-ups of each participant's life-plan, along with follow-ups of participants' performance in the educational training programs. This allows the program staff to measure changes, identify special needs of participants and to provide the appropriate response to these needs. The evaluation section of the component examines whether the program it's serving its purpose.

2) The "psychosocial, drug use intervention and self-care" component involves the development and implementation of a psychosocial intervention aiming at transforming personal goals, improving well-being, strengthening family cohesion and local networks, and facilitating access to medical treatments including those related to substance use, abuse/dependence. 3) The "Leadership, employment, job- seeking and performance skills, and entrepreneurship training" component focuses on human development through the acquisition of occupational skills, the planning of strategies to improve access to job opportunities and to increase the likelihood of being employed, and the gaining of entrepreneurial skills to become self-employed through the creation of their own businesses. 4) The "Education to finish secondary school, and to improve access to technical and university training" component comprises a strategic plan to allow youth to return to secondary school programs and to prepare to enter technical or university programs. This component provides information to identify career options and strategies to prepare for national exams to enter higher-education programs. 5) The "Engagement in sports and recreational activities improving social cohesion" component provides better use of free time through physical and cultural activities aiming at strengthening social cohesion and reducing the risk of becoming exposed to violence and to substance use. Finally, 6) the sixth component "The restitution of citizen rights to youth street gang members" involves developing activities to promote social citizenship participation and to improve youth's conflict resolution skills.

Operating units:

Starting in 2016, operating units (OU) (to date nine units have been formed, one per commune) were created to visit and support youth in their usual daily activities. The staff from these units advises and supports youth so they can reach their desired life goals. These OU are comprised by:

1) Community liaisons are individuals living in the neighborhoods who are well known and respected by the community and street gang members in the area. There is one liaison per street gang in the program. Community liaisons are leaders who continuously enhance the participation of youth in all activities of the program. Given that community liaisons know the street gang slang, their interaction styles, and have gain the trust of the gang member, they can better connect with these gangs and promote their participation in the program.

2) Peace promoters from the National Police are police members trained in the development of social strategies to reduce violence in communities, with a special focus on helping youth involved in street gang-related activities. Peace promoters are in charge of implementing activities for each of the six components of the program. They also look after participants, providing support and advice, so participants have a better chance to reach their life goals.

One important variation of the "TIP -Youth without frontiers" compared with other similar models is the participation of peace promoters from the National Police in the implementation of core activities. While risking the participation of some street gang members in the program who may worry about their presence in the area, the participation of these peace promoters is a key aspect that offers a different perspective about law enforcement to youth. As participants interact with the peace promoters, they start building better relationships that can eventually permeate the whole community. Peace promoters also help improving safety in neighborhoods, not only in a preventive manner during the implementation of program activities, but also displaying enforcement operations when homicides occur to prevent future retaliations from those seeking revenge. The articulation of Police peace promoters with the educators for life, the commune coordinators and the community liaisons, help build a stronger core-operating unit that is capable of connecting with youth at risk to offer them alternative opportunities to reach their goals in a safer environment.

3) "Educators for life" are psychologists and social workers working in the implementation of activities for each of the six components of program. Similar to the peace promoters from the National Police, they look after a number of participants to help them focus and continue to work towards achieving their life goals. There is one educator for life and one peace promoter per two/three street gangs in the program.

4) Commune coordinators are professionals with a social sciences degree, or similar, with experience in community/social work, project development and administration. There is one commune coordinator per commune. Coordinators are in charge of planning, developing and monitoring activities from the six components that will be implemented by the peace promoters and the educators for life in the commune that they coordinate. Each commune coordinator is also in charge of developing activities for one specific component of the program. They share these activities with other commune coordinators, who in turn plan, deliver and monitor these activities in their own commune. Therefore, commune coordinators have a dual responsibility, coordinating all activities in their commune, and also developing activities for a specific component of the program. In addition, commune coordinators are also in charge of keeping records of all activities, information about active/inactive participants (those who continue or to stop being part of the program) and of other important field events that may affect the youth's participation in the program.

Finally, the National Police Peace Promoters coordinator and the Cisalva Institute Project Director follow up and coordinate all activities regarding technical and security issues of the program, based on the information provided by commune coordinators.

The OU direct interaction with youth is based on a behavioral-change model in which OU participants used the methodological principles of the intervention to design and implement different activities. The initial process involves the acknowledgement of the youth group and its participants, and the establishment of communication channels through which trust is built. Once participants have gone through the characterization process, the UOs start providing psychosocial services and activities of the "psychosocial, drug use intervention and self-care" component. As described above, the purpose of this component is to transform personal goals, improve well-being, and strengthening family cohesion, to enhance social active participation and strengthen social capital. These activities, which happen at the street gang territory, are delivered by the educators for life and the peace promoters who have previously planned the activities with commune coordinators. The community liaisons follow up each participant on the daily duty and continuously supports participants to enhance their participation in all program activities.

In addition, to improve access to the health system, the OU identify the individual's type of affiliation to the health system,whether is contributive (monthly payments proportional to income earned) or subsidized (no payments to the system given low or no income). If families or participants are not affiliated to the system, the OU provides information to participants so they can start the affiliation process according to their income and possibilities. The OU also provides elements to identify domestic abuse and the public services available to abused victims, and provides information about the risks associated with substance use and information on public services providing alternatives to substance use problems. The OU also works with participants to identify all other basic needs and initiates a process to identify private and public services that the city could serve to participants.

Implementation of the "TIP -Youth without frontiers" intervention

In 2016, 661 youth belonging to 34 street gangs (from 8 communes) joined the "TIP -Youth without frontiers" program. In addition, 773 youth joined the program in 2017 and 673 also joined in 2018. Of the 2107 youth characterized (baseline surveyed) up to 2018, 67.3% were males, 26.2% were between ages 12 to 16, 64.1% were between ages 18 to 25 and 9.7% were between ages 26 to 28. Also, 67.2% were single and 20.3% were living with a partner, 32.8% reported having at least one child. Also, 78.5% were living in stratum 1 (with the lowest economic status), 68.4% belonged to the subsidized health insurance system and 9.1% were not affiliated to the health system. A small number of these participants had a high-school degree (26%), and 11.4% reported working in formal jobs. The most common illegal drug was marijuana (55.7%); 25.6% of participants were currently using two or more illegal drugs. Also, 10.8% had been incarcerated/detained in a reclusion center, 33.1% were victims of physical or psychological violence in the past six months, and 54% have felt they were at risk of dying while doing activities with their gang.

Services provided to participants:

The program was able to connect all participating youth with medical, dental, sexual and reproductive health services. Individuals who were not in the health system were assisted in the application process to become part of it. Also, all individuals participated in activities of the psychosocial care model that addressed prioritized family, drug use, management of grief, and gender aspects.

Also, the program facilitated the return of participants to educational programs including secondary school, courses to prepare for the national admission test for higher education, and technical/ university programs. To December 2018, 171 had taken courses to prepare for the national admission test, and 294 had taken this. Also, 97 participants have been enrolled in technical employment related programs, and 101 have completed a technical course in motorcycle repair trainings. From the ones with a secondary school degree, four were admitted in university programs. Participants who did not have a high-school degree attended secondary schools.

In addition, 600 participants have received in-job training, 480 with the security and justice secretariat and 120 with the peace and citizen culture secretariat. A total of 268 participants have become environment promoters of Cali's environmental protection administrative department (DAGMA) and 93 have become peace and culture promoters from the Cali's peace and citizen culture secretariat. Also, 63 report working independently (self-employed) and 55 were working as employees in private companies. About 70% maintained their jobs through all the intervention up to December 2018.

To date 56 physical spaces have been intervened by youth (restorative actions in the community) that included painting of murals, cleaning streets and sowing plants in different parks. Also, multiple recreational and sport activities have been developed, such as soccer tournaments, visits to city parks and visits to movie theaters. Also, a demonstration of their artwork was performed in a city museum for three weeks. In addition, a group of participants worked on a theatre, which they performed at one of the most important city theaters in the city (sold out audience). Moreover, six invisible barriers (frontiers) have been eliminated in four of the eight communes (communes 13, 14, 15 and 16).

Analyzing changes in street gang-related homicides in intervened communes

Homicide occurrence for each commune from 2015 to 2018 was obtained from Cali's inter-institutional security observatory, the official source of information on all homicides in the city (Guerrero, 2015; Gutierrez-Martinez et al., 2007; OSC, 2016). The security observatory keeps track and analyzes all homicides identified by institutional sources in the city (e.g., National Police, Forensic medicine, Public Prosecution Office, Public Health services). In weekly meetings personnel from each of the four information sources discuss all homicides evidence and classify each case according to different motives including coexistence (e.g., personal disputes, domestic violence) violence related to robberies/theft, organized crime related activity (e.g., drug cartels), and street gang-related violence. For the purpose of examining the impact of the program on homicides that are responsive to changes in street gang activity, only street gang-related homicides are analyzed in this study. Changes in street gang-related homicides from 2015 (baseline) to 2017 and 2018 are presented as percent change increase/ decrease.

Change in street gang-related homicides

The intervention was evaluated in eight communes were the program was implemented. In 2015, commune 15 had the highest number of street gang-related homicides (n = 79), followed by communes 20 and 14 (n = 74 and 73, respectively) and then by communes 13 and 21 (n = 63 and 60, respectively) (Table 1). From 2015 to 2016, there was a 50% reduction in street gang-related homicides across intervened communes (Table 1). The strongest reductions were observed in communes 18 (82% reduction) and 16 (73%), followed by communes 20 (54%), 15 and 21 (both with a 52% reduction). Communes 13 and 14 (40%), and commune 1 (30%) also had important reduction in homicides (Table 1).

Table 1 Street gang-related homicides in intervened communes with the TIP program

Source: Cali's inter-institutional security observatory

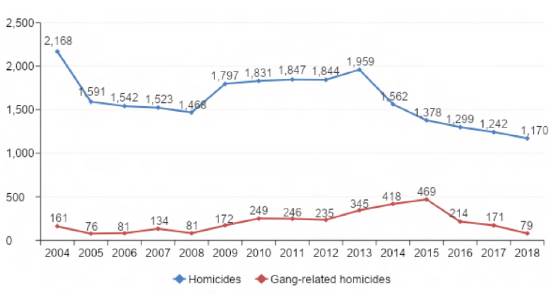

From 2015 to 2018 there were also important reductions (of 73% or greater) in street gang-related homicides across all communes (Table 1). When analyzing all communes together, there was an overall 80% reduction in street gang-related homicides. In commune 1 there were no homicides in 2017 and 2018 (Table 1). Figure 1 shows an increasing trend in the number of street gang-related homicides in Cali from 2009 to 2015 (year with the highest number of these homicides in the series); however, a change in trend was observed starting in 2016, with a marked reduction in the number of street gang-related homicides that continued until 2018.

Source: Cali's inter-institutional security observatory

Figure 1 Homicides and street gang-related homicides in Cali, Colombia, 2004-2018

Table 2 Street gang-related homicides in intervened communes with the TIP program, by month and year

Source: Cali’s inter-institutional security observatory

Regarding the month of occurrence of these events, reductions from 2015 to 2018 occurred across all months varying from 46% in April to 100% in September (Table 2).

Discussion

The present study describes the methodology of the "TIP -Youth without frontiers" approach to reduce violent behavior among youth street gang members in Cali, Colombia and its implementation between 2016-18. It also examines the association of the program with a reduction in street gang-related homicides during the first three years of the program. This intervention sought to improve the life of street gang members through access to multiple health and education services, providing job opportunities, and providing psychosocial support with conflict resolution skills. This strategy was aligned with other deterrence interventions (Braga et al., 2018; Butts et al., 2015) that aim at reducing the burden of youth violence, intervening on structural and proximal risk factors for street gang involvement.

Analysis showed a large reduction in observed street gang-related homicides in communes that received the intervention, a decrease by 73% or more from 2016 to 2018 was noted. It was also observed that homicides continued to go down throughout the study period, suggesting that the continuation of the program keeps contributing to the reduction of homicides in these areas. These reductions are much higher than the ones observed in other similar interventions developed in the United States ((Skogan et al., 2009; Webster et al., 2012) and other countries such in Brazil (Abramovay, M. 2003; Waiselfisz, J.J. & Maciel, M. 2003.).

These findings should be taken with caution, given that the descriptive approach used in this study cannot not rule out that external causes (e.g., the presence of local or national public policies) could explain the observed changes. Future studies using experimental/quasi-experimental approaches (Skogan et al., 2009; Webster et al., 2012), e.g., using control cities not exposed to similar interventions could provide additional evidence of the program effects on homicides. However, the fact that there were major reductions in street gang-related homicides in the intervened communes is an important finding indicating that youth lives are not being lost at the rate they were occurring in 2015. The fact that invisible barriers (frontiers) were eliminated in half of the communes provides additional evidence of a reduction in violent confrontations in these areas.

Previous studies (Skogan et al., 2009; Webster et al., 2012) show how similar approaches to reduce street gang-related violence have confronted multiple obstacles and opposition. For example, the cure violence model developed in different cities in the United States have faced difficulties in creating new programs due to lack of organization and community leaders, limited community buy-in, and inconsistent program funding (Butts et al., 2015).The "TIP -Youth without frontiers" have also faced difficulties mainly on inconsistent program funding. The program depends on resources from the Mayor's office and uncertainty about whether or not the new incoming administration will continue funding the program, creates tension among the program staff and participants.

In conclusion, According with this intervention aims at transforming the lives of street gang members in communes at economic disadvantage in Cali using a public health approach has worked with a significant impact. The six components of the program holistic approach are needed to assure the results like to improve access to services, reduce substance use, develop personal skills, and improve access to education and employment opportunities, while improving the restitution of citizen rights to youth street gang members in their transformation and reintegration to become an active member of their society. Important reductions in street gang-related homicides were observed in the intervened communes, suggesting that the program have contributed to the reduction of violent behavior in these areas.