Introduction

Criminal behaviour has been the subject of study by various disciplines, which at different times have theoretically and empirically addressed its origin, persistence, desistance and intervention in the field of social control (Redondo & Garrido, 2013). Developing perspectives that range from the individual to the social and from the micro to the macro, multiple theorists have contributed various explanatory postulates regarding this phenomenon (Tittle, 2006).

Content in the individual differences-focused approaches to criminological research (Tittle, 2006) is the “personal identity” approach, which was widely disseminated and problematised in the criminology of the 1970s and 1980s (Tittle, 2006). Among the precursors of this proposal are the works of Kaplan (1972, 1975), Howard Becker’s labelling approach (2009) and the research carried out by Schwartz and Stryker (1970).

In general, according to the authors mentioned above, criminal behaviour would be a consequence of the search for meaningful self-concepts, as well as for a prestigious identity (Katz, 1988), or adapted to stigmatisation (Becker, 2009). More articulated formulations of the concept of identity in criminology were developed by Kaplan (1972, 1975, 1980, 1982), who stresses that motivation towards criminal behaviour originates in a weakening of adherence to the norm and in the enhancement of personal self-esteem. For their part, Schwartz and Stryker (1970) identified the different elements constituting the deviant identity, detailing multiple dimensions of the self. In addition to the above, in his work Outsiders, Howard Becker (2009) specifies that individuals who engage in prolonged deviant behaviour organise their identity around this type of behaviour.

Although the identity perspective achieved a significant degree of dissemination and problematisation in its first stage, it lost momentum after its lack of articulation and adaptation with other criminological postulates was criticised (Tittle, 2006). This isolation, combined with other aspects designated as unfavourable, placed it in a condition of reductionism. Part of the earliest questioning of the perspective came from Gibbs’ (1966) critique of the new theories situated in social reaction, including that of labelling. His remarks were directed at the ambiguity as to whether these approaches were explanatory theories or conceptual approaches to deviant behaviour. Furthermore, he argued that they did not explain the variability in crime incidence among populations or individuals and did not justify why certain behaviours were considered deviant in some societies and not in others. In a similar vein, Wellford (1975) pointed out that the assumptions of the labelling theory (Becker, 2009) did not coincide with the existing data, so he called it into question and suggested that criminologists explore other alternatives for studying criminal behaviour. To this were added criticisms of its theoretical underpinning, which was pointed out as insufficient and a source of methodological difficulties for measuring elements alluding to the definition of self (Stryker & Craft, 1982). In the same vein, Tittle (2006) noted:

A number of central questions remain that could be addressed only if theories of the self were adapted to other theoretical processes, such as general frustration, learning and social control. It is still not entirely clear why and how the search for identity leads to definitions of the self that result in criminal behaviour. (p. 13 )

However, the concept did not cease to be investigated and new approaches emerged from various theoretical positions and disciplinary fields. These new enquiries addressed phenomena such as deviant subcultural identity, deviant group identification, criminal identity residues, and various cognitive, affective and change aspects of identity associated with delinquency (Asencio, 2013; Brezina & Topalli, 2012; Bubolz & Lee, 2021; Copes & Williams, 2007; Hutchison et al., 2008; Unnithan, 2016).

More recent approaches have defined the concept of “criminal social identity” (Boduszek et al., 2016; Boduszek & Hyland, 2011) and “criminal identity” has been defined as: “the sense of self, based on values that distance them from the social order established in the global culture, but which they share with their social reference group, validating and promoting social patterns that place them in a countercultural condition” (Zambrano-Constanzo et al., 2022, p. 72). This shows that research on the relationship between identity and crime is still ongoing and forms a complex field of study in which different theoretical and empirical approaches converge.

We consider it important to highlight the relevance of the concept of identity and its relationship with criminal behaviour, as well as its presence and dialogue with both classical and contemporary criminological proposals, in addition to its more specific thematic approach, which shows its consistency, versatility and broad possibilities for revitalisation. In the same way, we believe that with its revitalisation the concept can become a substantial resource for intervention, given its empirical and practical correlates, studied from the qualitative and quantitative sides. Thus, it could nourish the development of different public security policies and social interventions, which consider criminal identity, its individual, contextual and subcultural projections as key elements. In this way, the understanding, prevention, approach and social reintegration regarding the delinquent subject would be broadened.

Therefore, this article aims to analyse the specific uses of the concept of identity associated with crime in the main criminological theories and the proposals of other related disciplinary fields, highlighting the possibilities for its revitalisation. The research questions are: what is the theoretical role of the concept of identity associated with crime in the different criminological perspectives that address it, and what are the characteristics of the concept of identity associated with crime that would make its revitalisation valuable?

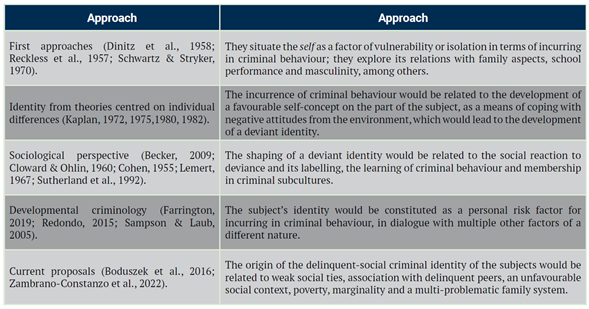

To this end, we will first outline the initial enquiries specifically situated in the self. Subsequently, we will address the perspective of identity as part of theories centred on individual differences (Tittle, 2006), from where we will move on to approaches based on the sociology of deviance. Next, we will present the postulates of developmental criminology, culminating with the most current approaches, from which the concepts of “criminal social identity” and “criminal identity” have been delimited. We will end by drawing the main conclusions from our review. Table 1 summarises the evolution of the concept of identity associated with delinquency, which is presented below.

Methodology

This article is based on a literature review (Roussos, 2011) of predominantly criminological theories and works. Its elaboration was carried out as a result of the review of the state of the art corresponding to the first author’s doctoral thesis, which addresses the issue in question based on a qualitative approach.

The literature search was carried out in the Web of Knowledge, Scopus and Scielo indexing databases. The following keywords and Boolean operators in English and Spanish were used to broaden the scope of the review: “criminal identity”; “self AND criminology”; “self AND delinquency”; and “identity AND criminology”.

The following questions guided the literature selection and analysis: 1. What is the criminological proposal of the author(s); 2. What is their approach towards offender identity; and 3. What role does identity play within their proposal? In addition to the individual questions, the inclusion criterion was also based on the number of citations of the work and its historical relevance to the subject matter.

The order in which the main findings are presented was determined using a chronological and a disciplinary criterion, which allowed us to present the large number of selected approaches in a parsimonious and concatenated manner.

Identity and crime, first approaches

The relationship between identity and crime began to be studied quantitatively during the 1950s, by means of research that placed the self at the centre of the development of criminal behaviour.

Given that the concept of self will be referred to based on different approaches, we will establish as a general definition that it is the human characteristic that arises from the reflective capacity to imagine oneself from the point of view of others (Mead, 1934). Complementary to this, the definition of self-concept proposed by Rosenberg (1979) specifies that it refers to all of a person’s thoughts and feelings about him/ herself, and delimits three dimensions for it: self- referential dispositions, physical characteristics and identities.

The research of Reckless and his collaborators (Reckless et al., 1956; Reckless et al., 1957) and those of Dinitz and his collaborators (Dinitz et al., 1958), postulated that the self could act as a factor of vulnerability or isolation with respect to the development of delinquent behaviour. Their studies focused on low-income adolescents, their family networks and school performance. Their research aimed to explore the components of the self that underlie potential isolation in terms of the emergence of delinquent behaviours. This work found a relationship between the maintenance of a favourable self-concept and the absence of law-breaking behaviour. Subsequently, they found that an unfavourable self-concept was related to young people’s engagement in delinquent behaviour.

This work was continued by Lively et al., (1962) who related the stability of self- concept in relation to isolation and vulnerability to the emergence of delinquent behaviour. Their research found that the self- concept developed in adolescence remained resistant to change when there were no relevant external influences to modify it, which in turn was effectively linked to a greater presence or absence of delinquent behaviour. The studies put forth by Lively et al. (1962) gave rise to the identification of the self as one of the most tangible elements with respect to the emergence or withdrawal of delinquent behaviour.

Much of this incipient work was summarised in the publication of Reckless and Dinitz (1967) in which they emphasise the relevance of the self in terms of adolescents’ involvement in delinquent behaviour. In addition, they propose practical projections of their findings applied to the prevention and intervention of delinquent behaviour in adolescents.

At the same time, Schwartz and Stryker (1970) published a study with a quantitative approach that included elements of symbolic interactionism (Mead, 1934). These authors approached the phenomenon by combining a vision of the self as the centre and organisation of any type of behaviour, but at the same time seeking to understand specifically the origin of deviant behaviour, considering cognitive, affective and personal aspiration aspects, among others, as part of the structure of the self.

In the work mentioned above, it is argued that the most appropriate theoretical perspective on deviance is one that situates the actor in a continuous process of searching for, constructing, validating and expressing a self, whose identity emerges on the basis of social interaction. In line with this, the authors set out the different elements that constituted deviant identity, denoting multiple dimensions of the self, such as self- evaluation, variability and masculinity. Based on previous work by Stryker (1964, 1968) they argued that the self was constituted in a differentiated, organised and complex way, composed of discrete identities that maintained their origin in designations based on different social positions of the subject, which include deviance and its validation.

Stryker and Craft (1982) would update this research about a decade later. In this work, the authors complement and refine what was postulated in the 1970 publication, incorporating findings alluding to the variability of the self, its content and the influence of significant others. They also point out the need to consider structural notions of identity salience and commitment to social norms, which may also be deviant within the social structure.

This review contains nuances that are quite critical of the work of Schwartz and Stryker (1970). They emphasise the need for solid theoretical postulates regarding the self as the origin of criminal behaviour, which they also extend to the work of Reckless et al. (1956, 1957).

Identity as part of theories focusing on individual differences

The so-called “individualist theories” (Tittle, 2006) would contain postulates alluding to personal defects, aspects of learning, rational choice, control and identity. This section surveys the approaches of the identity perspective, as a description of the other proposals would go beyond the scope of this section.

The concept of identity in criminology owes its relevance, to a large extent, to the labelling approach (Becker, 2009; Lemert, 1967). However, the postulates developed by Kaplan through his quantitative research (1972, 1975, 1980, 1982) are among the most elaborate in terms of the identity associated with crime (Tittle, 2006). Kaplan’s identity perspective suggests that the emergence of criminal behaviour is due to a lack of personal self-esteem or a measure to cope with negative environmental attitudes towards the subject (Kaplan, 1980). Thus, criminal deviance would result from an individual’s search for meaningful self-concepts (Tittle, 2006). This would connect with interpretations that link the development of a deviant identity with the search for prestige (Katz, 1988) and with others that highlight the role of adaptation to the social reaction that stigmatises the deviant through labelling (Becker, 2009). From this perspective, the self occupies a fundamental place, particularly because of the influence that the appreciation of third parties would have on it and because the development of a favourable self-concept would be a key motivator of behaviour, including criminal behaviour (Tittle, 2006).

In line with the above, Kaplan (1972, 1975, 1980, 1982) highlights the concept of “self-deprecation”. According to this author, people are naturally oriented towards increasing favourable attitudes towards themselves and avoiding negative ones. In this way, the evaluations that the subject perceives about him/herself in his/her environment will influence the definition of his/her personal meanings and the conditions in which they occur. When the influence mentioned above generates an unfavourable self-evaluation on the part of the individual (self- deprecation), the commitment to the social system and its norms weakens and motivations to break with the latter emerge (Tittle, 2006). Thus, a weak commitment to norms in an adverse social context and the possibility of strengthening one’s self-esteem in the face of negative evaluations, would enhance the emergence of criminal behaviour as a response to a process that would include frustration, stigma and deviance as compensation.

Deviance and certain behaviours, not necessarily criminal, would allow the individual to avoid contexts or subjects that produce or reinforce negative feelings about him or herself. Delinquency itself would be a direct response of the subjects to the source of discomfort, through which they would express contempt and rejection of the norms that sustain it (Tittle, 2006). Similarly, the formation of gangs, for example, would show association and engagement with peers who reject the norms that have produced their self-loathing and at the same time reinforce their self-affirmation and identity. The latter connects the concept of identity described with the shaping of a subculture as proposed by Becker (2009), Cloward and Ohlin (1960) and Cohen (1955).

Finally, from this perspective, criminal behaviour is useful to the offender to an extent beyond the instrumental, the key element being the reinforcement of self-esteem and self-concept (Tittle, 2006).

Identity and crime from a sociological perspective

In contrast to the approaches of the positive school in the field of criminology (Buil, 2016) the postulates of the sociology of deviance focus on the characteristics of society and their impact on individual behaviour, which would not be the exclusive result of the decisions of the subjects (Barrios, 2018). Three micro-sociological theories that include approaches to the formation of an identity related to delinquency are described below.

Differential association

The American sociologist Edwin Sutherland developed the differential association theory and first published in 1924 (Perez, 2011). It emerged at a time when there was a keen discussion regarding the aetiology of criminal behaviour, its individual characteristics and its link to poverty and marginality (Buil, 2016). It argues that individuals become criminals through a process of learning the techniques transmitted by their groups of belonging (Redondo & Garrido, 2013). In these groups, the new members would be exposed to the expression of motivations, forms of perception and attitudes linked to criminal behaviour (Cooper, 1994).

Thus, a person will offend or be more likely to offend if he or she holds more favourable than negative definitions and attitudes towards this type of behaviour (Sutherland et al., 1992). These definitions will, through socialisation and association with others, go hand in hand with forming an identity associated with values, interactions and goals related to offending.

One of the main premises of this approach is that people in general, but young people in particular, whose personality and identity is still in the process of consolidation, maintain a permanent coexistence and relationships with other subjects, who can be either respectful or transgressors of the law and its limits (Akers & Jennings, 2019; Vásquez, 2003).

Sutherland proposes his theory on the basis that the learning of deviant behaviour would emerge from the interrelation and communication of subjects within a framework of close relationships, involving elements such as frequency, duration, priority and intensity in terms of interpersonal relationships (Sutherland et al., 1992, cited in Sánchez, 2014). This aspect of his theorising connects his arguments with those of symbolic interactionism (Sánchez, 2014), a proposal that addresses the construction of identity in subjects through their interactions and interpersonal ties in different social fields.

The primary groups would be the ones that would transmit to the subjects in a primordial way the values, social goals and behaviours associated with each type of delinquency or deviance, which would leave no room for biological theories or those that allude to heredity (Cooper, 2005; Sutherland, 2016). Similarly, the explanation of delinquency would not be linked to community vulnerability, moral weakness, poverty, or disorder (Sanchez, 2014) but mainly to excessive contact with environments in which the subject learns deviant behaviours through differential association.

Based on this approach, it is essential to emphasise that criminality is learned just like any other human behaviour (Sutherland et al., 1992). This, together with its link to symbolic interactionism, would be connected to the formation of an identity with criminal characteristics in the subject, sustained through the prevalence of favourable definitions of crime associated with their interpersonal relationships.

Subcultural perspective

The framework of subcultures became especially popular during the 1950s, particularly with Albert Cohen and his work Delinquent boys: The culture of the gang (1955). Articulating approaches developed by Merton (1938), Cohen advocates that deviant behaviour would not be explained exclusively by the presence of anomie, the mismatches between the means and ends for social success, and the subsequent frustration associated with them. Thus, he adds complexity to the analysis of delinquency by introducing the notions of status and social recognition as ends, which would be achieved through gang membership (Cohen, 1955). These concepts account for central aspects of both personal and social identity associated with criminal activity, highlighting its interpersonal dimensions.

Later, the authors Cloward and Ohlin (1960) in their book Delinquency and opportunity: A theory of delinquent gangs, recognise the strong tensions generated by the disparities between the licit means available to achieve certain goals, especially social and economic ones, so they incorporated elements of Merton’s proposal (1938) to the subcultural perspective, as well as principles of differential association (Sutherland et al., 1992). In this way, they connect the aspects related to learning, anomie and its conjugation with the approaches of Cohen (1955), integrating to a large extent the perspective of three major theories of that era (Buil, 2016) deepening and giving breadth to the subcultural perspective.

One of the central tenets of subculture theories is that habitual offenders tend to associate almost exclusively with other offenders, so that they maintain a shared outlook on life, which over time becomes a ‘tradition’, thus forming a subculture (Perez, 2011). What would define a deviant subculture would be a criterion of disobedience that would allude to the norms transgressed by its members, particularly in terms of their characteristics and quantity (Gil, 2018). When the circumstances encourage it, people with problems, without access to institutional alternatives for solutions, meet, unite and give rise to a subculture of this type. Through it, they would find social acceptance (Vásquez, 2003). This issue is also raised in labelling theory (Becker, 2009).

According to Cohen (1955) the maladjusted youth has three possibilities: to join the cultural field of the middle class, with fewer conditions to compete; to give up his aspirations and integrate into the culture of other young people (not necessarily delinquents); and to join a delinquent subculture. It should be noted that from the perspective of labelling (Becker, 2009) once the labelled subject assumes an identity consonant with that label and joins groups that share it, deviant subcultures result (Alvira, 1975; Becker, 2009; Sancho, 2014). This shows the subcultural projection of the concept of criminal identity, as well as its potential for direct dialogue with theories of subcultures and labelling.

Labelling theory

The labelling approach emerged during the 1950s and gained strength and visibility in the following decade (Buil, 2016). Its main referents are Edwin Lemert and Howard Becker (Vásquez, 2003) who gave delimitation and depth to the concept of “labelling”, focusing on the social reaction to deviant behaviour rather than on the study of its aetiology (Sancho, 2014). From this perspective, deviants are those who break the established set of rules and are therefore labelled as incapable of living in the social group that has determined them (Becker, 2009). This would lead to them being “labelled” both formally and informally (institutionally and socially) (Gunnar, 2019). Thus, reference is made to “thief” when someone has committed a theft, or “murderer” when someone has committed a homicide, which implies the imposition of and commitment to an identity of the perpetrators of such acts (Alvira, 1975). According to Lemert (1967) there would be a distinction between initial and subsequent deviant acts, which would be essential to understanding the persistence of the criminal behaviour of individuals. Primary deviance would have rather circumstantial characteristics, linked to individual factors (maladjustment, misbehaviour, among others). Conversely, secondary deviance would be the product of social reaction (institutional intervention) to primary deviance, resulting in labelling. With the establishment of the label, the chances of initiating a process in which the subject would be accepted and identified as deviant increase considerably, enabling the development of a criminal career (Gunnar, 2019; Lemert, 1967) sustained by a process of social ostracism and marginalisation.

By being labelled, a person is deprived of social acceptance due to the connotation and negative features of the label, which would lead him/her to seek acceptance by relating to other subjects or groups with whom he/ she shares the label. This process would provide both elements that would improve their impression and schemas regarding the deviance and the label itself, thereby transforming their identity (Gil, 2018). The key issue of secondary deviance is persistent offending (Sancho, 2014) and the emergence of a criminal identity. Closely linked to the above, it is necessary to highlight that deviance is agreed upon by social groups, which institutionalise norms that define and sanction transgressions, a process from which labels result (Vásquez, 2003). By virtue of this, deviance would be a consequence of the application of sanctions to those who are identified as transgressors, which would give rise to one of the axes of the critical perspective of this approach, which evidences that racial, social and economic elements would play an important role in the management and sanctioning of delinquency. Thus, it would be more rigorous in the case of the same acts regarding (for example) poor young people as opposed to others from the middle or upper middle class (Becker, 2009; Gil, 2018; Sancho, 2014).

Identity and crime from developmental and life course criminology

Developmental criminology deals with the study of changes in antisocial behaviour during the life course, offering an explanation of its patterns and variations throughout the life course, and focuses on its phases and the motivations of the subjects to commit crimes (Requena, 2014). Its theoretical postulates approach the phenomenon of crime from a perspective centred on the individual, non-static and in dialogue with social and interactional elements (Cuaresma, 2017; Requena, 2014).

Theory of integrated anti-social cognitive potential

The theory of integrated antisocial cognitive potential (Farrington, 2019) has been developed by the English psychologist David Farrington, who based it predominantly on the results of the longitudinal Cambridge study on delinquent development (Farrington & West, 1990). His proposal is an integrative approach to crime at the individual level. It brings together psychological elements as well as those identified by the sociology of deviance, for example, subcultural, labelling, social control, economic and rational choice aspects (Cuaresma, 2017; Ward, 2019). The central tenet of this theory is that the individual potential to engage in criminal behaviour, called “individual antisocial potential”, is mediated by short- term (intra- individual) and long-term (inter-individual) risk factors, more widely known in criminological literature as dynamic and static risk factors. In addition to the above, emphasis is placed on the cognitive assessment of opportunities, consequences and possible victims that the subject makes prior to committing a crime (Requena, 2014). This theory indicates that labelling as a consequence of criminal behaviour would have a direct link with its recurrence (Ward, 2019). This at the individual level, and in relation to what is postulated by Becker (2009) would be connected to the delimitation of an identity associated with crime.

Antisocial potential alludes to the predisposition or capacity that each person has to engage in criminal behaviour, a matter that would present variations in terms of life experience, socialisation and psychological characteristics such as impulsivity (Farrington, 2019). Differences in these elements would produce offending behaviours in the short term (lower potential), as well as the development of chronicity and persistence in offending behaviours (long term, higher potential) (Ward, 2019).

According to Farrington (2019) long-term (inter- individual) risk factors include: (a) antisocial patterns: parents linked to offending, peers linked to offending and neighbourhoods with high crime rates; (b) aspects of parenting and socialisation: dysfunctional parenting patterns and dysfunctional families; (c) influences on motivation and long-term direction: low income, unemployment and school failure; and (d) life events and impulsivity. On the other hand, short-term (intra- individual) risk factors include: (a) cognitive processes: decisions and cost-benefit appraisal; (b) motivators: boredom, anger, substance use and frustration; and (c) opportunities and victims.

The first-mentioned factors denote individual differences in the likelihood that a subject will engage in criminal behaviour, while the second-mentioned factors denote the conditions and situations in which subjects are likely to commit crimes (Ward, 2019). Criminal identity would fit within the long- and short-term risk factors, linking with those that indicate socialisation, individual characteristics, social contexts and cognitive aspects, which, to varying degrees, are addressed by the micro-sociological proposals presented in this article. Finally, Farrington (2019, 2003) makes, among others, the following assertions with regard to offending behaviour across the life cycle: (a) the frequency of offending and the severity associated with it will peak during adolescence; (b) the younger the age of onset of criminal activity, the greater its chronicity and stability throughout life, which would involve aspects of an identity associated with that chronicity and stability; (c) in addition, as a learning process, the consequences of offending will produce changes in the individual’s long-term antisocial potential and decision-making; (d) offenders tend to show more versatility than specialisation in terms of the crimes they commit.

Age-dependent informal control theory

The theory of age-dependent informal control has been postulated by American criminologists Robert Sampson and John Laub. The authors took as their basis data collected in the longitudinal study by Sheldon Glueck and Eleanor Glueck (1950) as well as the postulates of control theories, particularly the one put forward by Hirschi (1969). Their work aimed to elucidate the risk factors involved in the stability and change of individual-level criminal behaviour in adults over the life course (Sampson & Laub, 1993). For this reason, they addressed the factors present in the persistence and desistance of offending patterns (Requena, 2014). The authors proposed that criminal behaviour emerges when the links that subjects maintain at the social level and with other controlling agents are weak (Cammack & Van Eck, 2017) and emphasise that, irrespective of the life stage at which it occurs, all offenders desist with the strengthening of social bonds (Sampson & Laub, 2003). Family, pro-social friendships, work, marriage and parenthood would be key factors in inhibiting criminal behaviour (Hirschi, 1969). Its variations during life would allow explaining both its appearance and the return to conventional behaviour (Cuaresma, 2017). The presence of the aforementioned factors, understood as concrete events, is referred to as “turning points” (Requena, 2014).

This theory suggests that, even though individuals may have engaged in offending behaviour during adolescence, the development of social bonds and other instances of control during adulthood would still influence the desistance process (Cammack & Van Eck, 2017). Over time, and as a result of new findings, the authors incorporated elements of everyday activities and social practices into the core of their proposition (Ward, 2019).

The most influential factors in terms of the remission of offending behaviour patterns would involve: new situations concerning past experiences; contexts of supervision and possibilities of control, as well as social support; the modification and structuring of routines in terms of daily activities; and spaces that would catalyse the transformation of the subject’s identity (Sampson & Laub, 2005). In this way, identity would maintain a particular relevance, articulated with the other elements that the theory proposes, as well as with the subjective experience in both persistence and desistance from crime. Given the reference to the transformation of identity present in desistance, the approach to criminal persistence would allow us to refer to the presence of a criminal identity.

The triple risk for crime and delinquency model

The spanish psychologist and criminologist Santiago Redondo put forward the triple risk for crime and delinquency model (2015). This proposal parsimoniously regroups risk and protective factors linked to the emergence of criminal behaviour into three dimensions. The author himself has emphasised both the longitudinal and societal projection that his model proposes for the study and prevention of delinquency (Redondo, 2008). This makes it one of the most complete theoretical approaches currently in existence.

According to this author, criminal behaviour is the product of the specific convergence of risk factors of different kinds in each individual; the main sources of these are the following (Redondo, 2015):

Personal risks: individual characteristics, both biological and psychological, innate and acquired through learning. These include in particular elements of temperament, intelligence, impulse control, empathy and identity.

Risks in terms of pro-social support: low-income, dysfunctional families, parents with a criminal background and delinquent friends, among others. The author emphasises the relevance of this dimension and mentions the richness that sociological research has contributed to its delimitation; likewise, he emphasises that it does not explain criminal behaviour on its own.

Criminal opportunities: unguarded public spaces, high population density, poor street lighting, and victims and unprotected property. Linked to this source, the author proposes the concept of “differential vulnerability”, which measures the relative amount of opportunity for crime according to the particular context or person.

The triple risk model does not pose risk and protective factors as opposites of each other, but as variables comprised of extremes that would define their status as protective or risky. For example, impulsivity would be at the risk end, while self-control would be at the protective end (Redondo, 2008) which would be part of the innovation of this proposal.

In conjunction with the above, the combination of sources (a) and (b) would lead to the estimation of ‘antisocial motivation’, representing the degree of the individual’s willingness to engage in criminal behaviour. The effect of antisocial motivation and the number of criminal opportunities the subject is exposed to would result in the ‘risk of antisocial behaviour’ (Redondo, 2015). Both measures would provide substantial input for crime prevention and intervention, and it is noteworthy that their main characteristic is the ideographic approach to the phenomenon. Although a structure determined by the model is used, its application would be specific to each individual, considering only their particularities (Redondo, 2008).

It is possible to observe the presence of the concept of identity as part of the dimension of individual risk, which would also contain elements of learning, which, as discussed in the section on the sociology of deviance, have ample possibilities for dialogue with interpersonal and subcultural aspects, present in this case in the risk dimension of pro-social support. This would give rise to the possibility of analysing the formation of a delinquent identity in the subjects throughout their life cycle, as developmental criminology proposes, giving relevance to their ideographic qualities and their relationship with the maintenance and desistance from delinquent behaviour, in a similar way to that which Sampson and Laub (2005) propose.

Current approaches and proposals

During the twenty-first century, various works have addressed the relationship between identity and crime from different disciplinary fields. In this section, some research from different theoretical perspectives will be presented, as well as two prominent current formal proposals on criminal identity.

Recent thematic approaches

As part of the last decade’s work on identity and crime, it is possible to mention the quantitative research of Asencio (2013). In it, self-esteem is addressed as a moderator of the assessment made by third parties regarding the self, taking a position based on the theory of identity control (Burke, 2007). The author contrasts her proposal in a population of subjects with both criminal and pro-social identities. Her conclusions point to the fact that self-esteem plays a moderating role in terms of the evaluations that third parties make of individuals; she also highlights its impact on identity with all its multiple facets.

In addition to this, there is the publication by Ashton and Bussu (2020) which explores with a qualitative approach the perspectives that a group of young offenders hold with respect to engaging in criminal behaviour, membership in criminal groups and criminal exploitation. It is worth noting that its theoretical framework and findings are developed on the basis of elements of the social identity (Tajfel & Turner, 1979; Turner et al., 1987) of the participants, who at the time of the research were part of a community intervention programme.

Finally, there is the work of Bubolz and Lee (2021) who using a qualitative research approach addressed elements of identity and delinquency. This work focused on the residual roles of identity (Ebaugh, 1988) present in a group of gang members with habits, behaviours and/ or preferences linked to their gang membership stage. According to what was proposed, these behaviours can be manifested passively or actively, involving symbolic, behavioural and worldview dimensions with different depth and scope.

Criminal social identity

As part of recent developments, one of the most substantial contributions regarding the role of identity in criminal behaviour has been made by Boduszek et al. (2016), who through their quantitative research (Boduszek et al., 2021; Boduszek et al., 2013a, Boduszek et al., 2013b) have developed the concept of “criminal social identity” (Boduszek et al., 2016; Boduszek and Hyland, 2011).

This proposal articulates the social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) and the self-categorisation theory (Turner et al., 1987). It states that individuals who become delinquent do so because of the presence of a persistent criminal identity, which emerges as a result of an identity crisis that results in the development of weak social ties, poor parental control, exposure to a criminal context, association with delinquent peers and joining criminal groups to protect self-esteem (Boduszek et al., 2016).

Although this perspective has gained consistency within criminology today, offering a theoretical model and evidence, the authors acknowledge that it still requires further empirical support (Boduszek et al., 2016). Nevertheless, their contribution is substantive and represents an important part of the current revitalisation of the concept.

Construction of criminal identity

Among the minority of publications in Spanish are the qualitative and quantitative research papers compiled by Zambrano-Constanzo et al. (2022). This publication describes various research studies that have addressed the concept of identity in relation to delinquent activity in the youth population, in addition to the proposal of a definition for the concept of delinquent identity.

In their article from the beginning of the century, Zambrano-Constanzo and Pérez-Luco (2004) set forth, based on a constructionist and sharply critical approach, the central aspects involved in the development of an identity committed to delinquent activity in young lawbreakers from marginalised sectors. Factors such as poverty, the absence of pro-social referents, marginality, the presence of anti-social peers and a multi-problem family system are underscored at the individual and combined levels as key elements in the socialisation process of adolescents living in these contexts. These scenarios would be directly related to the shaping of delinquent identity, as delinquent behaviour, and its affirmation, is a way of adapting to them.

Zambrano-Constanzo et al. (2022) delimit their approach to the self and the social representations present in the process of shaping delinquent identity, again emphasising the influence that contextual, family, social and institutionalisation factors have on its development and settlement. In this work, they also give an account of the multiple investigations that have shaped their proposal, which represent more than 20 years of research.

Conclusions

The analysis and articulation of postulates offered shows that, by virtue of its presence and approach based on the different proposals presented, the theoretical concept of identity linked to criminal behaviour maintains ostensible possibilities for revitalisation.

Although during the last century this concept and the theories that predominantly addressed it (Becker, 2009; Kaplan, 1972, 1975, 1980; Reckless et al., 1957, 1956; Schwartz & Stryker, 1970) fell into decline due to criticisms of their reduced connection to other criminological postulates, their theoretical underpinning and reductionism (Stryker & Craft, 1982; Tittle, 2006; Wellford, 1975). In the exercise carried out in this paper, its theoretical and empirical consistency and versatility have been highlighted.

The latter is possible to observe directly and indirectly and is evident in the relationship between the identity approach based on labelling and criminal subcultures (Cloward & Ohlin, 1960; Cohen, 1955) or by way of its link to learning observed in differential association (Sutherland et al., 1992). We can add the thematic approaches carried out more recently, which are nourished by different theoretical and disciplinary positions (Asencio, 2013; Ashton & Bussu, 2020; Bubolz & Lee, 2021).

Likewise, it is important to emphasise that the concept is present in current theories of developmental criminology (Farrington, 2003, 2019; Redondo, 2008; Sampson & Laub, 2005), in which it is generally considered a risk factor. In this sense, it would have an important role to consider for the appropriate prevention, prediction and intervention of delinquency, as well as for understanding the phenomenon at an individual level and in its interaction with other risk factors.

Despite the aforementioned shortcomings, efforts are still being made today to offer a solid theoretical proposal with sufficient support. Such is the case of Boduszek et al. (2016) and Zambrano-Constanzo et al. (2022) who, based on different theoretical approaches, have made substantive contributions to the development, delimitation and consolidation of the concepts of criminal identity and criminal social identity, both conceptually and empirically. The value of the revitalisation of the study of identity associated with crime based on criminology and criminal sciences stems from its versatility and theoretical transversality. Its role and presence in micro-sociological proposals, developmental criminology and more recent approaches, all of which are currently valid and presented in this article, are proof of this. Whether the theory is based on the self and its conformation, in relation to social reaction, criminal subcultures, learning or as an individual risk factor, the deepening of its study would lead to a more precise conceptual delimitation. In this way, it would support empirical investigations with greater possibilities of offering evidence regarding its different postulates, which could translate into a valuable input with concrete practical projection in terms of the prevention and tackling of criminal behaviour.

Part of the practical importance of revitalising the concept of identity associated with delinquency, through crime identity (Zambrano-Constanzo et al., 2022), criminal social identity (Boduszek et al., 2016) or another approach, lies in the fact that by deepening and delimiting its characteristics and dimensions it would be possible to design intervention plans for both juvenile and adult offenders based on their measurement and specific approach. This is something that to some extent risk factor-based proposals (Redondo, 2015; Sampson & Laub, 2005) in general already propose; however, the development of a programme centrally based on a process of change of this type of identity, involving its learning, subcultural, contextual and family association aspects, could make a substantive difference in terms of prevention, desistance and recidivism, as highlighted by Boduszek et al. (2021). This could materialise through the design of individual clinical strategies, combined with interventions that address and enhance the different components of social reintegration (family, work, interpersonal, among others).

Finally, this work is part of the effort to revitalise the identity perspective within criminology and related sciences, which is why it joins the other approaches mentioned in its contents, particularly the most recent ones. It intends to give consistency and scientific relevance to the concept, to deepen the understanding and approach to the criminal phenomenon and those who embody it.1