Introduction

Since the 1930s, the impacts of business on society have been recognized as an important issue to be considered by organizations (Carroll, 1979). As a result, corporate social responsibility (CSR) and stakeholder concepts have been widely discussed in the academic arena as part of the argument that organizations should take responsible actions in the interests of the company's stakeholders (Freeman, 1984; Frederick, 1994; Wood, 1991) rather than only shareholders. A form of CSR that has seen increasing use by and interest in from both marketing practitioners and academics is cause-related marketing (CRM). CRM has become a representative philanthropic trend among businesses, with more and more companies supporting a specific cause (Chang & Lee, 2008). Particularly, some managers view CSR activities as opportunities to strengthen their businesses while contributing to society at the same time. Some examples of this practice are (1) McDonalds®, which created the Ronald McDonald House Charities of Mexico, which provide healthcare services, food, housing, and transportation support for children from 0 to 18 years of age, (2) Danone®, which allocates a percentage of its sales to help children battling cancer, and (3) Pedigree®, which helps dog shelters take care of their animals.

Particularly, the literature has found that CRM programs can offer numerous benefits to companies undertaking this practice (Gupta & Pirsch, 2006; Luo & Bhattacharya, 2006; Van den Brink, Oderken-Schroder, & Pauwels, 2006). For example, supporting a cause can increase a company's sales. A report from GoodPurpose annual global research states that monthly purchases of brands supporting a cause increased by 47 % between 2010 and 2012 (GoodPurpose, 2012). An increase in revenue is another benefit for companies supporting causes. For instance, Fortune 500 companies spend $15 billion dollars a year purely on CSR, and those that increased their budget for this purpose by at least 10 % between 2013 and 2015, experienced increased revenue (Novick O'Keefe, 2016). Additionally, according to a 2017 Cone Communications CSR study, 87 % of American consumers would buy a product based on the brand's support for an issue they care about.

Research on this topic has determined that fit between the cause and the brand (De Jong & Van der Meer, 2017) as well as consumer involvement with the cause are important determinants of the effectiveness of these types of campaigns (Hajjat, 2003). For example, brand/cause fit has been found to influence consumer choice (Pracejus & Olsen, 2004), consumer attitudes towards a brand and ad (Gupta & Pirsch, 2006; Nan, & Heo, 2007), purchase intentions (Gupta & Pirsch, 2006; Prabu, Kline, & Dai, 2009), and brand loyalty (Van den Brink, Odekerken-Schroder, & Pauwels, 2006).

Research has also examined the role of the affinity that consumers hold, or involvement that consumers exhibit, for the cause and how this involvement influences CRM campaign effectiveness (Grau & Folse, 2007; Hajjat, 2003). In such a context, affinity and involvement are defined as the degree to which consumers consider a cause to be personally relevant (Grau & Folse, 2007). However, as suggested by Lafferty and Edmonson (2013), in CRM where the consumer's main interest is the product, the existence of a cause may convince consumers to buy that brand over another if they believe that the cause is important, even if it is not necessarily personally relevant to them. However, almost no research has addressed whether consumers prefer to support certain types of causes more than others (e.g., human-related vs. non-human-related) and if so, how this preference influences variables such as brand evaluations and purchase intentions.

Therefore, the objective of this paper is to determine whether the cause category supported by a business through a CRM campaign has an impact on consumers' perceptions and behavior. This paper builds upon the self-categorization theory to evaluate human vs. non-human causes and their effects on brands and purchase intentions (Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987; Turner, Oakes, Haslam, & McGarthy, 1994). Self-categorization theory proposes that people recognize themselves as part of the human being group as opposed to animals and other non-humans according to the principle of similarity and difference (Totaro & Marinho, 2017; Trepte & Loy, 2017; Turner et al., 1987; Turner et al., 1994). Hence, it is argued that a company with a human CRM campaign will obtain higher benefits in terms of consumer's brand evaluations and purchase intentions than those with a non-human cause-related marketing campaign.

Overall, managers face the challenge of promoting CSR activities strategically to deliver positive effects to the company, something that few have managed to achieve. Therefore, although marketing researchers and practitioners have long focused on consumer involvement with a cause and its effects on CRM effectiveness as a form of CSR, opportunities remain to study how the cause category might play an important role in explaining the success of CRM campaigns. Specifically, this paper proposes a categorization of causes (human vs. non-human) that may help marketing managers strategically decide which types of causes to support.

This paper is structured as follows. First, a literature review on CSR and CRM is presented to provide a research framework for the study's hypotheses. Second, the experimental methodology of the research is described. Finally, the results are discussed and conclusions are drawn, which are used to identify managerial implications of the findings.

Literature Review

CRM as a Form of CSR

The concept of CSR has been widely discussed for several decades. Melé (2008) emphasizes the difficulty of identifying and organizing the large range of existing approaches to the concept of social responsibility. For this reason, consensus is still lacking regarding an exact meaning of CSR. Mohr (1996) grouped CSR definitions into (1) multidimensional definitions and (2) definitions based on the societal marketing concept. The multidimensional definitions outline the general obligations that companies are considered to have. For example, previous researchers have defined corporate responsibility in terms of companies' actions and decisions that go beyond the economic and legal spheres (Davis, 1960; Carroll, 1979; McGuire, 1963). Others have defined CSR either as a firm's voluntary effort (Acosta, Lovato, & Buñay, 2018) or as an obligation to society and to improve its environment (Frederick, 1994; Heald; 1957). Additionally, CSR has been defined as a commitment of resources by a company to attend to social problem areas, such as pollution, racism, and poverty (Hay, Gray, & Gates, 1976; Wood, 1991).

However, considering CSR as a business activity that translates into more sustainable practices for the firm and its stakeholders makes it possible to assume that activities within a firm should be embedded into this perspective. From this perspective, financial, managerial, and marketing practices should be expected to be more socially responsible. Therefore, the societal marketing concept refers to satisfying the market's needs in a way that preserves or improves consumers' and society's well-being (Kotler, 1991). CSR definitions based on the societal marketing concept are more abstract than multidimensional type definitions. For example, Luo and Bhattacharya (2006) broadly define CSR as a company's activities and status related to its perceived obligations to society and its stakeholders. In contrast, the less abstract definition of Mohr, Webb, and Harris (2001) states that CSR is an organization's commitment to minimize or eliminate harmful effects of its own activities and to maximize the beneficial impacts on society. In general, these two types of CSR definitions are similar in that they both uphold the view that companies have obligations to society and their stakeholders and should therefore take actions to attend to and positively impact problems that may be present in a society.

Currently, companies face increasing pressure to be socially responsible while maintaining profitability. In terms of marketing, Smith (2008) defines ethical branding as a response to consumer pressure on firms. In the same vein, CRM is considered as organizations' attempt to be socially responsible and is defined as "the process of formulating and implementing marketing activities that are characterized by an offer from the firm to contribute a specified amount to a designated cause when customers engage in revenue-providing exchanges that satisfy organizational and individual objectives" (Varadarajan & Menon, 1988, p.80). With this definition in mind, a firm implements CRM to achieve the following two objectives: improve corporate performance and help social causes (Varadarajan & Menon, 1988).

Cause Category and Willingness to Support.

For a company to be socially responsible in a strategic sense, one of the most important issues is to determine the focus of CSR support. Stakeholder theory proposes several groups or individuals, such as owners, customers, employees, environmentalists, society, and governments, who affect or are affected by the company's goals and achievements (Freeman, 1984). This paper proposes that CRM campaigns will be centered on different groups of company stakeholders, and that consumers self-identify with certain groups through self-categorization. In this sense, self-categorization refers to a transition from a personal to a social identity by identifying social categories that result from cognitive groupings according to the principle of similarity and difference (Totaro & Marinho, 2017; Trepte & Loy, 2017). This categorization process occurs not only at a social level, but also at a more general level.

According to the self-categorization theory, people recognize themselves as part of the human being group as opposed to animals and other non-humans (Turner et al., 1987; Turner et al., 1994). This theory assumes various levels at which the self could be categorized, including personal, social, and human levels. Specifically, at the personal level, a person recognizes him/herself as an individual different from other individuals. At the social level, the self is identified as part of a group, which can be family, friends, or an organization. Finally, at the human level, the self is considered to be part of a more general collection, namely the human being group (McFarland, Webb, & Brown, 2012; Turner et al., 1987; Renger & Reese, 2017).

The theory of self-categorization can be relevant to understanding why consumers prefer one brand-promoted cause over another. According to this theory, individuals integrate with social groups of reference that are viewed as congruent with their own attributes and values. This self-categorization into reference groups helps satisfy psychological needs such as belongingness and meaningful experience, and overall, helps people make more sense to their lives. This results in a stronger identification with the group into which a person classifies his or herself (Kim, Lee, Lee, & Kim, 2010). Considering these points, this paper proposes that the self-categorization theory can be relevant to classifying the type of cause that a company can promote through their C SR efforts because customers can naturally determine which causes support the social group to which they belong.

Extant work on CRM has addressed the issue of consumer involvement with the cause and the influence of such involvement on consumer responses to the cause (Barone, Norman, & Miyazaki, 2007; Bester & Jere, 2012; Gupta & Pirsch, 2006; Myers, Kwon, & Forsythe, 2013; Lafferty, 2009; Trimble & Rifon, 2006). For example Patel, Gadhavi, & Shukla (2017), found that consumer's cause involvement influences their attitudes towards the brand and purchase intention. However, personal relevance or involvement with a cause may not necessarily drive consumers to buy one brand over another. As suggested by Lafferty and Edmonson (2013), in CRM where the consumer's main interest is the product, the specific cause may convince consumers to buy that brand over another if they believe that the cause is important, even if not personally relevant. In fact, it has been suggested that allowing customers to select the cause the brand should support is more likely to increase their purchase intentions (Al-Dmour, Al-Madani, Alansari, Tarhini, & Al-Dmour, 2016).

Additionally, previous work on the factors affecting consumer's support for charities has found that consumers are more concerned with the types of assisted groups rather than the financial management of charitable organizations (Guan-Yu & Chih-Ping, 2005). Other research investigating the differences in people's willingness to support causes because of their geographic location and type of problems addressed has found that people are more likely to support local or regional causes rather than national or international ones and are more willing to support causes addressing human issues than environmental issues. Interestingly, these characteristics have been found to have a greater impact on consumer purchase decisions than the company's specific donation amount o to the cause (Ross IIII, Stutts, & Patterson, 2011). The literature also shows that willingness to support the cause occurs when the CRM cause and the consumer's self-concepts match (Ho, 2017). Furthermore, Amezcua, Briseño, Ríos and Ayala (2018) found that consumer's preferences for a product increased when the product was linked to a social cause, but not when the cause was ecological. In general, these findings suggest that people's willingness to support is highly dependent on the type of cause.

As previously mentioned, CRM campaigns support different a wide range of causes. Lafferty and Edmonson (2013) identified four broad categories of common CRM causes: animal, environment, health, and human services categories. The animal category represents all causes that address any issue pertaining to animals, such as protection and rights. The environment category includes all causes related to environmental issues, such as reducing pollution and saving forests and rivers. The health category contains all causes that address human health matters, such as the prevention of and research into diseases. Finally, the human services category encompasses all causes related to human problems other than health, such as helping the homeless and aiding in disasters. This paper groups the health and human services categories into a general human-related cause category and groups the animal and environmental categories into a general non-human-related cause category.

Based on previous work, this paper argues that consumers may have preferences or be more willing to support certain types of causes compared with others without necessarily being involved with that cause. In this article, willingness to support refers to a person's inclination to promote the success of a social cause (Hsu, Liang, & Tien, 2005). Furthermore, this paper argues that consumers may be willing to support certain social causes over others due to their personal self-categorization. At the most general level, i.e. the human level, consumers identify themselves as human beings and thus do not identify with other non-human groups such as animals. It is expected that this identification will lead people to be more willing to support members of the group to which they most closely identify rather than groups with which they less identify. Therefore, based the self-categorization theory, this paper suggests that consumers will be more willing to support human-related causes than non-human-related causes.

H1: Cause category (human or non-human) influences consumer's willingness to support a cause. Specifically, consumers will show higher (lower) willingness to support human-related causes (non-human-related causes).

Willingness to Support and Consumer Perceptions of Brands.

A brand has been defined in the literature as a "set of functional attributes and symbolic values" that result from the process of associating those attributes with a product in order to add value (Hakala, Latti, & Sandberg, 2011, p.448). Previous studies on brand evaluations provide evidence about the factors that can influence this process. For instance, brand evaluations can be affected by consumer perceptions of a brand's identity, which refers to the set of brand associations that the company aspires to create through the brand's name, price, market positioning, logo, and symbols (Keller, 1993; Kotler, 1991; Martínez & Chernatony, 2004; Dodds, Monroe & Grewal, 1991; Van Osselaer & Janiszewski, 2001; Zaichowsky, 2010).

Extant research has determined that CRM campaigns can also influence consumer perceptions or evaluations of a brand. For example, consumer attitudes toward a brand can be enhanced by the use of cause-brand alliances-but only perceptions of brand-cause fit are favorable (Demetriou, Papasolomu, & Vrontis, 2010; Gupta & Pirsch, 2006; Lafferty,

Goldsmith, & Hult, 2004). In this context, fit can be understood as the perceived link between the firm's image, market positioning, and target market with the cause's image and constituency. This can be achieved, for example, if the selected cause benefits a similar consumer base as the one to which the brand caters, or if they both share similar values (Christofi, Leonidou, Vrontis, Kitchen, & Papasolomou, 2015). Nevertheless, other studies have found that consumer perceptions of a company can be improved through the latter's use of CRM campaigns regardless of the level of fit between the brand and the cause (Nan & Heo, 2007; Nan & Heo, 2007).

Given these mixed results, it becomes interesting to analyze other factors that may influence consumer's attitudes towards a brand that utilizes CRM campaigns. Previous research has suggested that the relationship between CRM initiatives and consumers' brand evaluations can be influenced by the consumer's support for the cause (Sen & Bhattacharya, 2001). For instance, willingness to support has been found to positively influence consumer brand evaluations of products whose companies support a social cause (Strahilevitz, 1999). Additionally, a study considering the effective use of CRM found that participants' attitudes towards a brand were improved because they were willing to support the cause sponsored by the company (Ross IIII, Stutts, & Patterson, 2011). In this manner, it is expected that consumers are more likely to evaluate a brand more highly when they are willing to support the brand's sponsored cause. In other words, it is expected that willingness to support will have a positive effect on consumers' brand evaluations.

H2a: Willingness to support a cause has a direct positive effect on brand evaluations.

It has already been discussed how consumers' attitudes towards and willingness to support the cause can influence brand evaluations (Bergkvist & Zhou, 2018; Patel, Gadhavi, & Shukla, 2017). These more positive brand image evaluations can possible occur when consumers identify with the cause because they are more supportive (Vanhamme, Lindgreen, Reast, & van Popering, 2012). Following such discussions, this paper argues that human-related causes are more likely to dovetail with consumer's self-concepts than non-human causes, resulting in higher levels of willingness to support human-related causes. Willingness to support, in turn, is expected to influence brand evaluations. Therefore, brand evaluations can be expected to be higher among consumers who are more supportive of the particular cause that the company is promoting. In other words, the relationship between type of cause and brand evaluations is expected to be mediated by willingness to support. Specifically, it is proposed that higher levels of willingness to support human-related causes mean that brand evaluations will be more positive if the company supports human-related causes than if it supports non-human-related causes.

H2b: Willingness to support will mediate the relationship between cause category and brand evaluations.

Willingness to Support and Consumer's Purchase Intentions.

Prior research has found that a company's CSR can positively influence consumer brand choice, purchase intentions, and willingness to pay (Barone, Miyazaki, & Taylor, 2000; Hustvedt & Bernard, 2010; Lee & Shin, 2010; Mohr & Webb, 2005; Prabu, Kline, & Dai, 2009). It has been demonstrated that consumers prefer to buy products from companies supporting a cause when those consumers are themselves willing to support that cause (Barone, Miyazaki, & Taylor, 2000; Robinson, Irmak, & Jayachandran, 2012). Personal involvement and affinity with a cause have been identified as important variables that impact brand evaluations; such variables are related to a customer's view of the cause's personal relevance (Grau, & Folse, 2007). However, willingness to support goes one step further; it requires a higher commitment from customers, i.e., they need to be willing to actively participate in supporting the cause.

For instance, Barone, Miyazaki and Taylor (2000) found that information about a firm's support for social causes could positively affect consumer choice when brands are viewed as similar in terms of substantive product features. Youn and Kim (2008) found that consumers report higher purchase intentions for products that support social causes than for products not related to social causes. Because consumers can feel like they are supporting social causes simply by purchasing products from companies that help those causes, it is proposed that the higher the willingness to support a cause, the higher the purchase intentions towards products supporting that cause.

H3a: Willingness to support a cause has a direct positive effect on purchase intentions.

Company-cause fit has been found to increase purchase intentions (Gupta & Pirsch, 2006). According to Robinson, Irmak and Jayachandran (2012), giving consumers the opportunity to choose the cause of a marketing campaign has a positive effect on their purchase likelihood and willingness to pay for campaign-associated products. Additionally, certain types of causes are more likely to influence consumers' purchase intentions because of their willingness to support (Ross IIII, Stutts, & Patterson, 2011). Furthermore, consumers' preference to purchase a brand's product increase if the product is linked to a campaign with a social cause, but not if the nature of the campaign is ecological (Amezcua, Briseño, Ríos, & Ayala, 2018). Based on previous studies, it is therefore expected that purchase intentions will be stronger for brand products supporting a human-related cause rather than for products that support a non-human-related cause as a result of consumers' willingness to support the type of cause. Therefore, it is hypothesized that the relationship between cause category and purchase intentions will be mediated by willingness to support.

H3b: Willingness to support a cause will mediate the relationship between cause category (human or non-human) and purchase intentions.

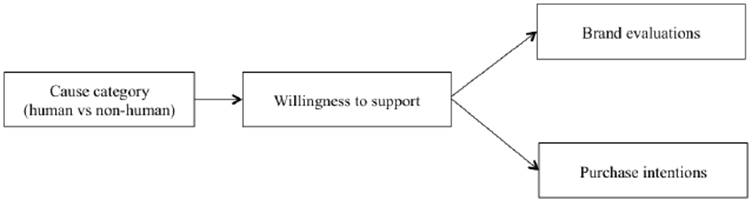

Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework proposed in the hypotheses previously discussed in this section. To test these relationships, an experimental approach was taken.

Materials and methods

Previous literature has assessed the uses of qualitative and quantitative studies. In particular, qualitative studies are preferred when the purpose of the study is to understand a phenomenon in a particular context (Bryman, 1984; Eisenhardt, 1989; Smith, 1983). Conversely, quantitative studies are more appropriate to test hypotheses and determine relationships, among other purposes (Bryman, 1984; Harkness, 2010; Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, 2004; Smith, 1983). Therefore, in this research, an experimental approach was selected to test the hypotheses.

Pre-test

Because willingness to support may vary within cause categories, it was decided to implement a pre-test prior to conducting the experiment. Specifically, a pre-test was applied to identify both human and non-human causes with low and high levels of willingness to support. A total of 37 people answered an online survey with a list of 11 Mexican human-related causes and nine Mexican non-human-related causes (see Appendix 1). Participants were required to indicate their willingness to support each cause. Willingness to support was measured using a single item (willing/ not willing to support) seven-point scale previously used in the literature on this topic (where 1 = lowest level of willingness to support and 7 = highest level of willingness to support) (Strahilevitz, 1999).

Based on the pre-test results, the causes with the highest and lowest means of willingness to support were selected for each of the two types of cause categories (human and non-human). Specifically, the human-related cause

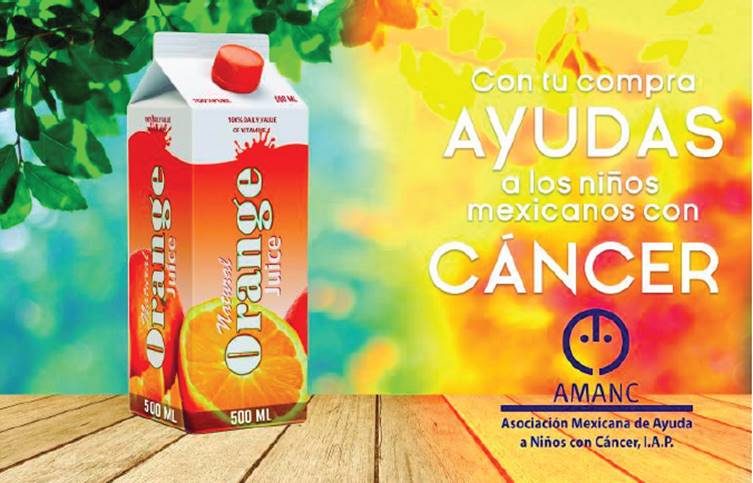

"Asociación mexicana de ayuda a niños con cancer, " which supports children battling cancer, had the highest rating for willingness to support (X = 5.89, SD = 1.491), and the lowest rating was for "Fundación mexicana de planeaciónfamiliar, " which provides family planning programs to society (X = 4.51, SD = 1.380). For the non-human cause category, "Reforestamos México," which supports Mexican forests, had the highest rating for willingness to support (X = 4.80, SD = 1.605), and "Asociación de empresas para el ahorro de energía en la edificación, " which creates energy-saving programs for businesses, had the lowest (X = 3.74, SD = 1.686) rating for willingness to support.

Overview

A growing body of literature suggests that statistical analyses of association, such as the causal steps approach or indirect effect approach, cannot determine causal links definitively because the mediator has not been manipulated (MacKinnon et al., 2002; Shrout and Bolger, 2002; Spencer et al., 2005; Stone-Romero and Rosopa, 2008). In this study, we manipulate WTS by including causes that were evaluated with low and high levels of WTS in the pre-test in order to provide experimental evidence that WTS affects the dependent variables.

Based on the results of the pre-test, a total of four ads for an unknown brand of orange juice were created for the experiment. The same ad was used for the four conditions, modifying only the name and logo of the type of cause that the product would supposedly support. The ads did not mention a specific donation amount (see Appendix 2 & 3). The purpose of this experiment was to test the proposed model. The experiment used a fictitious brand of orange juice to avoid effect of pre-conceptions participants might hold regarding a particular brand.

Sample and Procedure

A total of 137 undergraduate students from two different universities in northeast Mexico participated in this study. However, six cases had missing values in some of the dependent variables so they were eliminated; this resulted in a sample of 131 responses from individuals aged between 18 and 26 years (M = 21.58, SD = 1.667). All subsequent analyses are based on this final sample. Of the total, 53.40 % were women and 46.60 % were men.

Subjects were asked to participate in a product evaluation study (no information regarding the real purpose of the study was provided a priori). They attended a laboratory on campus where each of the participants completed an online survey using Qualtrics software. The software randomly assigned participants to one of the four conditions, with 24.40 % of the sample were assigned to the human high willingness to support condition and another 24.40 % assigned to the human low willingness to support condition, respectively. Similarly, 26 % and 25.20 % were assigned to the high and low willingness to support conditions of the non-human causes, respectively. First, participants were shown the orange juice ad for 15 seconds. After watching the ad, participants were asked to rank their brand evaluation, purchase intention, and willingness to support using the aforementioned scales. The scales appeared in that order and participants answered them one at a time without being able to see the next scale or go back to change answers; they were also not able to view the ad again.

Dependent Variables

Brand evaluations were measured on a three-item ("bad/good", "dislike/like", "nice/not nice") seven-point scale (Nan & Heo, 2007) (reported Cronbach's alpha=0.923). To measure purchase intentions, a three-item ("likely/unlikely", "probable/improbable", "possible/impossible") seven-point scale was used (Chattopadhyay & Basu, 1990) (reported Cronbach's alpha=0.970). All scales reported a Cronbach alpha greater than 0.70, which suggests good reliability (Nunnally, 1978; Peterson, 1994).

Results

Manipulation checks

Descriptive statistics for the four causes are presented in Table 1. Manipulation checks were also conducted to ensure that those causes in the low WTS condition did in fact have lower levels of WTS for the presented cause and that those in the high condition had higher WTS levels for the cause. Results of these manipulation checks confirmed that WTS was induced as intended, participants in the low WTS condition for the human causes reported significantly lower levels of WTS than those in the high WTS condition (Mlow = 5.130, SD= 1.635 vs. Mhigh = 6.530, SD = 0.803; t = 3.785, p = 0.000). Similarly, those in the low WTS condition for non-human causes reported lower levels of WTS than those in the high WTS non-human type of cause condition (Mlow = 4.180, SD = 0.999 vs. Mhigh = 5.180, SD = 1.629); t = -3.034, p = 0.004).

Table 1 Descriptive statistics for each cause.

| Cause | Type | WTS | BE | PI |

| "Niños con cáncer" | 6.530 | 5.531 | 4.615 | |

| Human | (.803) | (1.139) | (1.719) | |

| "PlaneacLón familiar" | 3.31L! | 4.5M | 3.406 | |

| {1.635) | (1.938) | (2.037) | ||

| "Reforestemos México" | 5.1HÜ | 4.79H | 3.929 | |

| Non-human | (1.629) | (1.518) | (1.920) | |

| "Ahorro de Energía" | 4.1HU | 4.265 | 3.2H4 | |

| (.999) | (1.315) | (1.619) |

Source: developed by the authors.

Model analyses

As previously mentioned, the experiment consisted of four conditions designed to manipulate the mediator variable (WTS) through the inclusion of causes with low and high levels of WTS for both human and non-human categories. However, for the next analyses, in order to test the model, the data for the two human causes were combined, as were the data for the non-human causes. As a result, only two types of causes (human and non-human) were used in the analyses.

The proposed model was analyzed using various techniques. First, a t-test showed significant differences in willingness to support the cause between the group that observed the human causes ad (x = 5.92, SD = 1.418) and the one that observed the non-human causes ad (x = 4.67, SD = 1.429; t statistic = 5.025, p < 0.01), thus supporting H1. Next, correlation analyses between the independent, mediator, dependent, and control variables were run (Table 2). Because cause category, represented by the variable "human," is a binary variable (where 1 = human cause and 0 = non-human cause), a point-biserial correlation (Kornbrot, 2014) was run to determine the relationship between the independent variables. This found a significant (p < 0.01) relationship with rpb = 0.405, which suggests low multicollinearity (Grewal, Cote, Baumgartner, 2004). Additionally, it was observed that brand evaluations and purchase intentions had a significant but moderate relationship (0.36 < r < 0.68) (Taylor, 1990).

Table 2 Correlation Analyses between Independent and Dependent Variables.

| Human | Willingness to support | Brand Evaluations | Purchase Intentions | Age | Male | |

| Human | 1 | |||||

| Willigness to Support | .405*** | 1 | ||||

| Brand Evaluations | .157* | .313*** | 1 | |||

| Purchase Intentions | .109 | .302*** | .621*** | 1 | ||

| Age | 056 | -.056 | -.071 | .022 | 1 | |

| Male | -.178*** | -.220** | .068 | .121 | -.038 | 1 |

Note: ***significant at 1%, **significant at 5%, *significant at 10%; variables where measured on a seven-point scale where 1=lowest level and 7=highest level, except for the dummy variables Human and Male where 1=human cause or male and 0=non-human cause or female respectively.

Source: developed by the authors.

To test H2a H2b, H3a, and H3b, a series of regression analyses were run using a bootstrapping simulation of 5,000 re-samples using a PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes, 2013). The regression results are provided in Table 3. As expected, regression 1 showed that the cause category represented by the dummy variable "human" had a significant effect on willingness to support (t = 5.025, p < 0.01), indicating higher willingness to support human causes, which provides further support for H1.

Additionally, regressions with brand evaluations and purchase intentions as dependent variables were also run using PROCESS. Some researchers have argued that a mediation effect can exist even if the relation between the dependent and independent variables is not significant (MacKinnon, Fairchild, & Fritz, 2007; Zhao, Lynch, & Chen, 2010). Therefore, even though the cause category (human cause) had no significant direct effect on brand evaluations or purchase intentions, willingness to support (the proposed mediator variable) did show a significant effect on both dependent variables (see Table 3), thus supporting H2a and H3a. The indirect effect was evaluated using the bootstrap test with PROCESS, which has been suggested to be more rigorous and powerful than the Sobel test (Zhao, Lynch, & Chen, 2010).

As expected, the indirect effect is positive for the three dependent variables at a 95 % significance level because their confidence intervals do not contain zero. For brand evaluations, the indirect effect is significant and equal to 0.382 (CI: 0.155, 0.741). Similarly, it can be stated that the relationship between the type of cause and purchase intentions was also mediated by willingness to support because the indirect effect is significant and equal to 0.469 (CI: 0.202, 0.851). These results provide support for H2b and H3b.

Table 3 Estimations Exploring the Mediated Effect of Cause Category on Brand Evaluations and Purchase Intentions.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Dependent | Willingness to support | brand Evaluations | Purchase Intentions |

| Constant | 4.672 | 2.740 | 1.851 |

| (0.174)*** | (.514)*** | (.567)*** | |

| Human | 1.250 | 0.161 | -.060 |

| (.240)*** | (0.2B5) | (-345) | |

| Willigness to Support | .328 | .375 | |

| (.093)*** | (.112)*** | ||

| Male | .465 | ||

| (.267)* | |||

| P statistic | 25.251 | 5.7BB | 6.454 |

| R squared | .164 | .120 | .092 |

| Adjusted R squared | .157 | .099 | .078 |

| p-value | .000*** | .001*** | .002*** |

Note: ***significant at 1%, **significant at 5%, *significant at 10%; means are based on a seven-point scale where 1=lowest level and 7=highest level.

Source: developed by the authors.

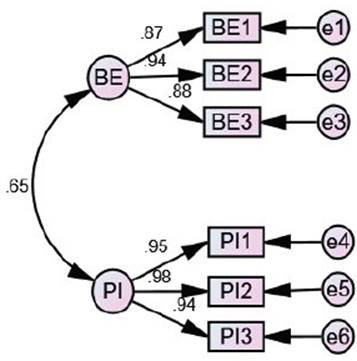

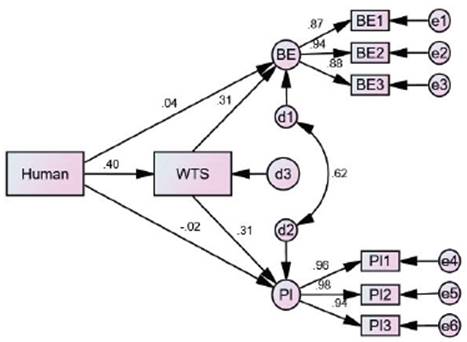

PROCESS relies on OLS regression, and it has thus been suggested that it could be susceptible to bias in the estimation of effects because of random measurement error. Therefore, structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis has been suggested to help manage the effects of measurement error by allowing the use of latent variables, which is not possible with PROCESS (Hayes, Montoya, Rockwood, 2017). Therefore, in addition to the regression analyses conducted using PROCESS, the complete model, including latent variables, was tested by SEM analysis using AMOS according to the following two steps. First, the measurement model was examined to test its reliability and validity with a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) (see Figure 2). Then the structural model was examined to test the research hypotheses (see Figure 3).

The standardized loadings, average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR), and Cronbach alpha values of the CFA are listed in Table 4. All standardized loadings were greater than 0.7 and significant at a 99 % confidence level. Additionally, the AVE values exceed 0.5, and the CR values exceed 0.7. These values indicate that the scales have a good convergent validity (Gefen, Straub, & Boudreau, 2000; Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, 2010).

Table 4 Standardized Item Loadings, AVE, CR, and Alpha Values.

| Factor | Item | Standardized item loadings | AVE | CR | Alpha |

| Brand Evaluations (BE) | BE1 | .869*** | |||

| BE2 | .939*** | .803 | .924 | .923 | |

| BE3 | .879*** | ||||

| Purchase Intentions (PI) | P11 | .955*** | |||

| PI2 | .976*** | .915 | .970 | .969 | |

| P13 | .938*** |

Note: ***significant at 1%, **significant at 5%. *significant at 10%; means are based on a seven-point scale where l=lowest level and 7= highest level.

Source: developed by the authors.

Discriminant validity was tested by comparing the square root of the AVE and the factor correlation coefficients. The results in Table 5 indicate that both factors have a square root of the AVE greater than the correlation coefficient (Gefen et al., 2000). Additionally, the shared variance (squared correlation) between the pair of constructs is lower (r 2 = 0.429) than each individual AVE, thus indicating discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, 2010).

Table 5 Factor Correlation coefficients and Square Root of the AVE.

| BE | PI | |

|---|---|---|

| BE | .896 | |

| PI | .655 | .957 |

Note: The square root of the AVE is shown in italic on the diagonal.

Source: developed by the authors.

In addition, several parameters were used to evaluate the model (see Table 6). The Chi-square statistic was used to assess the overall goodness of fit, and its results were significant (Chi-square = 11.702). However, this test is sensitive to sample size and model, so it was divided by the degrees of freedom, which produced a value lower than 3 (Chi-square/df = 1.351), indicating good model fit. Additionally, Table 6 includes the model measures of RMSEA, RMR, GFI, CFI, and AGFI along with the recommended model assessment values. All of these model fit indexes met the cutoff criteria, indicating good model fit (Schreiber, Nora, Stage, Barlow, & King, 2006). Furthermore, the results for total, direct, and indirect effects presented in Table 7 indicate that all hypotheses were also supported by the SEM analysis.

Table 6 Fit Indices of the Proposed Model.

| Fit Indices | Model Values | Recommended Values |

|---|---|---|

| Chi-Square | 11.702 | - |

| df | 16 | - |

| p-value | .764 | - |

| Chi-Square/df | .731 | <3 |

| RMSEA | 0 | <.08 |

| RMR | .033 | Near to 0 |

| GFI | .979 | >.90 |

| CFI | 1 | >.90 |

| AGFI | .952 | >.80 |

Source: developed by the authors.

Table 7 Results of SEM analysis.

| Relations | Total Effects (S.E.) | Direct Effects (S.E.) | Indirect Effects (S.E.) | Hypotheses | Supported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human ⇾ WTS | 405*** | .405*** | H1 | Yes | |

| (.079) | (.079) | ||||

| WTS ⇾ BE | 312*** (.111) | 3I2*** (.111) | H2a | Yes | |

| Human ⇾ BE | 162* | .036 | .126*** | H2b | Yes |

| (.094) | (.105) | (.049) | |||

| WTS ⇾ PI | 314*** | 314*** | H3a | Yes | |

| (.092) | (.092) | ||||

| Human ⇾ PI | .102 | -.025 | .127*** | H3b | Yes |

| (.087) | (-095) | (.044) |

Note: ***significant at 1%, **significant at 5%. *significant at 10%; means are based on a seven-point scale where 1 =lowest level and 7= highest level.

Source: developed by the authors.

Discussion

CRM campaigns are a form of CSR that have gained interest from marketing researchers and become a representative philanthropic trend in business, with more and more businesses supporting a cause (Chang & Lee, 2008). CRM programs have been found to confer numerous benefits upon the practitioner companies (Gupta & Pirsch, 2006; Luo & Bhattacharya, 2006; Van den Brink, Oderken-Schroder, & Pauwels, 2006). Considering that CRM campaigns make a proven favorable impact on business indicators because they improve brand evaluations and increase sales (Alalwan et al., 2016), there is an increasing organizational interest in partnering with charitable causes and other nonprofit organizations as a strategic marketing approach. However, it is not enough to merely promote CRM activities; companies must also strategically decide which type of cause to support (Amezcua, Briseño, Ríos, & Ayala, 2018; Guan-Yu & Chih-Ping, 2005; Ross IIII, Stutts, & Patterson, 2011; Howie, et al., 2018).

Managers face the challenge of moving to promoting CSR activities that deliver true value for both the business and society. A substantial body of literature has attempted to determine how this can be done and understand the factors that determine the effectiveness of a company's CRM activities. This paper attempted to extend knowledge about the topic by analyzing the role of cause category and willingness to support as key variables to improve brand evaluations and purchase intentions.

Following an experimental design in which participants had access to a version of wherein the brand supported either a human-related or non-human-related cause, consistent with self-categorization theory, the results offered sufficient evidence to suggest that cause category has a significant direct effect (standardized coefficient = 0.405, p < 0.01) on people's willingness to support. Specifically, willingness to support human-related causes was found to be higher than willingness to support non-human causes. This finding is consistent with the idea that a match between consumer's self-concept and the CRM campaign will lead to higher willingness to support such a cause (Ho, 2017).

Additionally, and in keeping with the literature (Barone, Miyazaki, & Taylor, 2000; Robinson, Irmak, & Jayachandran, 2012; Ross IIII, Stutts, & Patterson, 2011; Strahilevitz, 1999), results showed that willingness to support has a positive direct effect on both brand evaluations (standardized coefficient = 0.312, p < 0.01) and purchase intentions (standardized coefficient = 0.314, p < 0.01). Interestingly, willingness to support had a similar scale of effect on both brand evaluations and purchase intentions.

Furthermore, willingness to support was found to play a significant mediation role. Specifically, the results indicate that cause category has a significant indirect effect on brand evaluations (standardized coefficient = 0.126, p < 0.01) and purchase intentions (standardized coefficient = 0.127, p < 0.01) as mediated by willingness to support. Therefore, consumer's willingness to support offers a clear positive effect as mediator on the relationship between cause type on the one hand and brand evaluations and purchase intentions on the other. Specifically, brand evaluations and purchase intentions were found to be higher when the brand supported a human-related cause than a non-human-related cause, a difference ascribed to the higher levels of willingness to support human-related causes.

The results of this research contribute to the discussion of how certain strategic decisions in the development of CRM campaigns, such as determining the focus of the support, can affect customer perceptions and behavioral intentions of the brand and products. It is therefore proposed that companies categorize causes into human and non-human in an attempt to analyze possible outcomes. Furthermore, the results indicate that consumers prefer human-related causes over non-human-related causes, a preference that can influence the effectiveness of a company's CRM campaign by enhancing brand evaluations and, more importantly, increasing purchase intentions.

Conclusions

The findings from this research have both theoretical and managerial implications. First, this paper contributes to the theory of self-categorization by providing evidence of a circumstance in which people perceive themselves to be part of the human being group, as well as documenting the consequences of this self-categorization on marketing variables. Furthermore, the results advance recent discussions regarding what type of causes companies should promote by highlighting the importance of consumer's willingness to support as a requisite to improve both brand perceptions and purchase intentions.

Furthermore, the study findings also have implications for marketing managers. The results can offer guidance for companies when deciding upon an investment area and selecting a social cause to support. Because the experiment was conducted with a non-existing brand, the results are especially pertinent for new brands aiming to influence consumers perceptions and purchase intentions. The findings indicate that human-related causes offer greater benefits to the organization in terms of consumers perceptions and a higher sales likelihood. However, the findings do not suggest that non-human causes are not important or that organizations should avoid supporting them. On the contrary, the findings offer important insights for companies that choose to support non-human CRM campaigns in terms of understanding that consumers must identify with the cause in order for it to have the identified impact in terms of the marketing variables analyzed in the model. Therefore, marketing managers seeking to support non-human causes must identify how to help consumers achieve this identification. One possible approach could be to develop communication strategies that help consumers identify as much as possible with some aspect of the non-human issue to which the company is devoting its resources. Companies supporting non-human causes should engage the customers by conveying the relationship between the cause and human concerns.

As with all research, this study has some limitations. This study undertook a comparison between only two general types of causes (human and non-human), and future research could divide these two broad categories into more specific groups to determine which causes within the human and non-human cause categories have greater impact on consumer perceptions and behavior. Additionally, the nature of the quantitative methodology means that this research cannot provide a complete understanding of why consumers prefer one cause or another. It cannot be refuted that perhaps other reasons or theories not considered in this study could explain the preference for human-related causes over non-human causes. Future research could qualitatively investigate whether the self-categorization theory can fully account for consumer preferences to help human-related causes or if other factors motivate this preference that were not considered in this research.

The possibility also exists that the nature of the sample exerts an influence on the phenomenon in such a way that the expected effect is substantially modified. For example, if the sample were composed exclusively of young women with environmental tendencies, the result could have been very different. Therefore, it is relevant to conduct this experiment among different population segments according to their level of involvement in either human or non-human causes.

Furthermore, this study did not addressed the influence of personality traits on willingness to support, so future research could also measure personality traits and determine their influence on willingness to support, brand evaluations, and purchase intentions towards companies supporting human vs. non-human causes.

Finally, although the experimental results suggest that consumers having the same characteristics as the sample are more willing to support human-related causes, the intended aim here is not to stop businesses from supporting non-human causes. Instead, based on the results of this experiment, it is suggested that special attention should be placed on the selection of the cause, and perhaps future research could assess whether relating a non-human cause with human concerns could increase consumer willingness to support non-human causes.