Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana

Print version ISSN 1794-4724On-line version ISSN 2145-4515

Av. Psicol. Latinoam. vol.26 no.1 Bogotá Jan./June 2008

Art and human nature

Mirta Toledo*

* Independent artist, Buenos Aires, Argentina. The author wishes to thank Teresa Dunegan, Mauricio R. Papini, and Santiago Papini for helpful comments on earlier versions of this manuscript; visual artists Anita Knox, Cristina Minacori, and Antonio Pujía for making photographs of their works available for this article; and poet James E. Gray II for allowing transcription of his poem. Correspondence concerning this article may be addressed to Mirta Toledo, Balbasto 2253, 1406-Buenos Aires, Argentina. E-mail: purediversity@hotmail.com.

Fecha de recepción: septiembre de 2007

Fecha de aceptación: marzo de 2008

Abstract

This article presents a visual artists point of view about art. This view confronts the Eurocentric traditional cannon with some ignored, but valuable traditions, thus proposing a contra-canon. These ideas are examined on the light of a variety of sources, including prehistoric, pre-Columbian, and 20th century art expressions, in a variety of media, from sculpture to literature. Recent art expressions are characterized by their incorporation of minority values and perspectives that challenge universal views. Using samples of works from Latino and African American artists, the author shows that, even today, art is a means to know the world and its people, to exhibit personal life, to create personal symbolism, and to show ones identity or the search for it. Like the human nature it represents, art has multiple faces.

Key words: Latino art; African-American art; Diversity; Identity; Multiculturalism.

Resumen

Este artículo presenta un punto de vista del artista visual sobre el arte. Esta vision confronta el canon tradicional eurocéntrico con algunas tradiciones ignoradas pero valiosas, proponiendo así un contra-canon. Estas ideas son examinadas a la luz de una variedad de fuentes, incluyendo las expresiones artísticas prehistóricas, precolombinas y del siglo XX, en una variedad de medios, desde la escultura hasta la literatura. Las recientes expresiones artísticas están caracterizadas por la incorporación de valores de las minorías y perspectivas que retan a las visiones universales. Mediante una muestra de trabajos de artistas latinos y afroamericanos, la autora muestra que, aún hoy, el arte es un medio para conocer el mundo y su gente, para exhibir la vida personal, para crear simbolismo personal y para mostrar la propia identidad o la búsqueda de ésta. Como la naturaleza humana a la que representa, el arte tiene múltiples facetas.

Palabras clave: arte latino, arte afroamericano, diversidad, identidad, multiculturalismo.

Humans first feel the world and later think about it, therefore Art precedes Philosophy and Poetry comes before Logic.

Ernesto Sábato, 1996, p. 74 (authors translation).

What is art?

There are many definitions of art and every one of them is influenced by a particular historical, cultural, or aesthetic vision. Like pieces from a gigantic puzzle, each of these views provides a part of the whole true. Through history, art has been considered an expression of human necessity, a mere imitation of nature, a skill, a pure aesthetic expression, a means to produce beautiful objects, among many other definitions. But, perhaps, art as an experience is entirely individual, like love or solitude, according to Jiménez (2002, p. 52).

This article is neither a systematic and organized visit through universal art history, nor a script from an art historian or critic. It is the point of view of a visual artist about how art was used (from the beginning of time to the present) to question, answer, and express human nature. To do so, I used few examples of prehistoric and prehispanic art, as well as of contemporary Latino and African American artists, with the intention to show how these questions and the artists answers have survived criticism, censorship, and even persecution.

Art and Magic

Although there is substantial diversity of viewpoints, art is such a universal manifestation of the human spirit that we could easily conclude that it is an essential part of human nature. From the dawn of civilization, humans used art to communicate the history of a specific society, their knowledge, their fears before the universe and the mystery of life, and their religious beliefs. The ability of prehistoric people to produce objects of art probably reflects an emotional reaction to the conscious realization of being, as pointed out by Mohen (2002, p. 14).

Since their origin, the innards of art and magic have been intimately close together. The artist was the one possessing the magical language, painting in rocks or modeling in clay in order to bring the products of a good hunt or harvest, and to secure a womans fertility. The Venus of Willendorf, one of the earliest known representations of a human being, is a good example of art as a magic object. Dated to be about 24,000-22,000 years old (Witcombe, 2000), this Venus shows the relevance of women in Paleolithic rituals and, although figurative, it is also a symbol of fecundity and motherhood. It is considered one of the earliest representations of Mother Earth, a traditional goddess that appears in many different cultures around the world.

An example from another continent is the colossal Coatlicue, measuring about 3.5 m in height and dating to approximately 1487-1520. This Aztec Earth Goddess, represented in the act of giving birth, is the mother of the moon, the sun and the stars, all gods in the Aztec cosmology. This Earth Goddess embodies the concept that indissolubly melts the notions of birth and death: Everything comes from her womb and goes back to her womb, in order to be born again (Westheim, 1957).

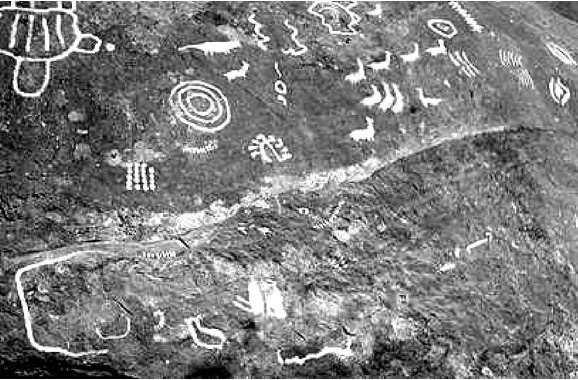

Art as a testimony of historical events also appears in some of the oldest human civilizations. As prehistoric artists left their realistic and beautiful paintings of bison herds in the walls and ceilings of natural caves like the ones in Altamira and Lascoux, in Europe, less is known about the cave paintings found in the Americas, where native people left a track of their existence (Mohen, 2002). For example, the indigenous inhabitants of Córdoba, in central Argentina, painted the story of the invasion of the Spanish conquistadors in meticulous detail. The paintings found at the hills of Inti Huasi, Veladero, and Colorado portrait the figures of these Spaniards with great precision and realism (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mural details of Inti Huasi. Cerro Colorado, Córdoba, Argentina. Photograph Stet of E. Acosta Vivas, Arte

rupestre de Cerro Colorado (Córdoba, Argentina), retrieved from http://rupestreweb.tripod.com/colorado.html

A striking feature in these pictographs is their detailed representation of the attributes of these soldiers, including their weaponry and clothing. Acosta Vivas (2004) described these paintings in the following terms:

Without a doubt, the indigenous artists had specific norms to represent the human figure, constituting the pictographic style of Cerro Colorado. However, they decided to break their canons to represent the unknown characteristics of the Spaniards and their animals, after seeing them for the first time. They chose to paint with realism everything that was standing before their startled eyes. (Authors translation.)

Art serving religion, promoting faith, and leaving testimony of the life, sacrifices, and miracles of the gods has been also a consistent manifestation throughout human history. Consider the Popol-Vuh, the sacred book of the Mayan in Guatemala, considered the most important text in any native language of the Americas (Tedlock, 1996). Originally, the stories compiled in the Popol-Vuh were a combination of hieroglyphic writing and paintings. Subsequently, they were translated into the Quiché language, but using the Roman alphabet, by a Mayan in 1558. Because the Spanish soldiers and missionaries were destroying sacred books, the manuscripts comprising the Popol-Vuh were hidden. At the beginning of the 17th century, father Francisco Ximénez found these manuscripts in a church, in Santo Tomás of Chichicastenango, and translated them into Spanish under the name of Book of the Council. Here is how the author of this ancient document described it:

This it is the first book of the antiquity, although its view is hidden to everyone who sees and thinks. Admirable it is its appearance and its story (that talks) of the time in which everything (what it is) in the sky and on the Earth finished forming, the quadrature and the cuadrangulación of its signs, the measurement of the angles, its alignment and the establishment of the parallels in the sky and on the Earth, in the four ends, the four cardinal points, as it were said by the Creator and the Training One, the Father of the Life, of the existence, the One for who we breath and act, Father and Creator of peace on the towns and its civilized vassals. (Anonimous, 1973, p. 14; authors translation.)

The Popol-Vuh originally created in a visual art form, came to us in another form of art: literature.

Pure Diversity

Starting in the 20th century, the definition of art became so wide that almost anything can be proclaimed art, no longer attached to rigid aesthetic canons or used as an instrument to provide a service for a particular government or religion. In the case of the visual arts, many times the concept precedes and accompanies the work, and a verbal explanation is required to comprehend the piece of art. Hermetism and ambiguity defined these expressions. Perhaps to understand contemporary art, we must have knowledge of aesthetic theory, art history and philosophy, as Oliveras (2001, p. 35) pointed out.

The viewer can not longer be a mere contemplator, a phenomenon that the philosopher Ortega y Gasset (1976, p.18) described in these terms: If modern art is not intelligible for everybody, this implies that its inner workings are not fundamental to human beings. It is not an art for the regular man, but for a very particular class of viewers who do not necessarily have more value than other viewers, but who are evidently different (authors translation).

Contemporary art and artists are influenced by the historical circumstances and problems of the society in which they are immersed and express that society in an individualistically creative manner. An example of the political influence in the visual arts can be found in the works of Cristina Minacori, an Argentinean painter who said that (López, 2001, p. 8):

The artist uses his point of view as a way of appropiation of the image that is spying. The painters vision analyzes everything: As a visual object, as a psychological situation, as a sexual delight, as social violence, as physical oddness. I am that spy, in search of a parallel reality, wanting to posses another world, the world of dreams, the aspirations, the taboo, the denied, the pain, the pleasure.

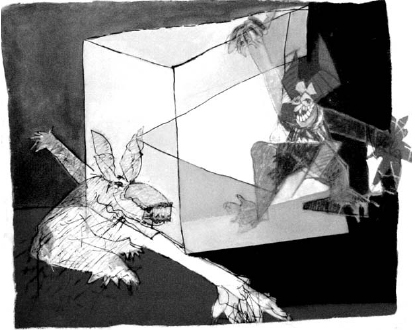

Minacori, who grew up during the military dictatorship of the 1970s in Argentina, named her last series Private Bestiary. Her monsters are a representation of a liberated society that finally, after years of political and social repression, had achieved freedom.

In Figure 2, Minacori represented a dictator as a clown who, even with make up, cannot hide his violent temper. The dog is an allegory of the peoples tendency to adapt to the circumstances because of fear—although the dog, apparently submissive, seems to be waiting for an opportunity to react. These situations and characters are also used as an excuse to show how color can invade form and dominate, thus creating illusory, dreamlike spaces and conveying an aesthetic message.

Figure 2. Number Five, from the series Private Bestiary, 1997, by Cristina Minacori. Private Collection, Texas, USA.

Photograph Stet courtesy of Cristina Minacori.

Art in all its expressions could be also used intentionally to shock the public, to cause an impact, thinking of art as a means of effecting social change The artists intention is illustrated in Figure 3. In his portrait of a suffering child, Argentinean sculptor Antonio Pujía showed the starvation and genocide endured by the people during the Biafra-Nigeria war, in 1967-1970. This image is also a good example of globalization and the extent to which an artist in another continent, without even stepping out of his own society, is moved by the events transmitted by the media. Pujía could empathize in such a way that he felt the urge to express his reaction to the Biafran massacre with his artwork.

Figure 3. Resigned, 1971, by Antonio Pujía. Private Collection, Sydney, Australia. Photograph by courtesy of Antonio

Pujía.

Art could be also a way to know the world, but for Eco (1992, pp. 88-89), art is more than that, it produces complements of the world, independent forms that are added to the existing ones, exhibiting their own laws and also, personal life (author´s translation).

My Forefathers, a poem by James E. Gray II (known under the pseudonym jgray44) expresses his aesthetic use of language to describe a personal, but universal feeling:

I stand in a blind spot…

A place where perception,

truth and reality part ways…

where belief and disbelief

coexist as partners

and require no justification.

I exist in a dangerous state,

emotionally hungry…

and feeling my mortality

deep in my bones…

I hear the voice of my

first Father… singing

of lust… and of blood

I hear the primeval blues

as murmuring in the dark

hear the rhythms of…

beaten chest, log,

drum, and heartbeat…

hear the hoots and hollas

across millennia

as the Sun God brings

hope and the promise

of the new day.

Over the centuries, only the art of particular groups has been defined as representing universal values, while the art of others has been excluded from this concept of universality. From the 20th century, the art of women adds to a cultural crisis:

…a culture of the difference has arisen: the minority values and perspectives, until now ignored […] we are in front of the loss of the dominant speech. […] This crisis questions and reveals the system of binary oppositions that underlay in it: white-black, good-bad, masculine-feminine (Serrano de Haro, 2000, p. 137).

Lorna Simpson, a contemporary African-American artist who confronts with her work the Eurocentric view of the American mainstream, is an example. Her installations are based on the analysis of the self-image of African Americans in the United States.

Among the subjects of Simpsons art is the experience of African American women contemporary American Society, a topic that encompasses issues of race and gender, African American hairstyles, which, over the centuries, have taken on social and political implications, have been some of her motifs. (The Collection, 2002).

Among the topics of her art is the experience of women in contemporary American society; Simpson explores the ways people, especially black women, are identifed, classified, and judged based on their physical attributes and personal styles. (Walker Art Center, 1998). White (1994, pp.72-73) described one of these conceptual pieces in these words:

In this installation piece, titled Wigs, she uses twenty-one lithographs of hairpieces of varying textures to illuminate how black women conform to or rebel against prevailing white standards by braiding, dying, weaving and processing their hair.

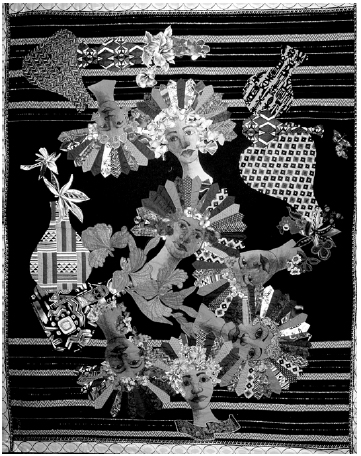

In contemporary art, one of the most appreciated characteristics is originality. Originality defines a style and adds value to a piece of art, even though the concepts of caducity and avant-garde change continuously. Although styles may come and go, certain issues seem to be more permanent and connected to the pursuit of originality. One such issue is the search for identity, an issue that could be explored with any media, including the quilt. According to Susan Roach (1992), the word quilt originates from the Latin culcita, meaning stuffed sack, mattress, or cushion, and comes to English from the French cuilte. Although individual quilt artists were long ignored in most art history treatments of quilting, the long history of quilting and patchwork spanning many centuries and cultures has received considerable attention. Anita Knox (personal communication, August 16, 2007), a painter, multimedia artist, and also a quilter, comments on this issue:

My first experience with cloth came from my mother. She told us because of color and racial barriers during the 1940s, African Americans werent allowed to try on clothes in the department stores. Instead, if she saw something she liked, she would look at the clothes in the windows, go home, draft her own pattern and make the dress or suit. She taught us to look at the quality of the fabric, the weave, texture and overall construction. Little did I know this would lead to my love affair with fiber.

The quilt shown in Figure 4, Face It, was completed in 2003. Knox expressed that the quilt itself is about facing life, a spirit-filled life. The women are all surrounded by flowers and leaves, especially the gingko leaves, from a tree that is the only surviving tree from the prehistoric era. For her, this is a symbol of longevity and good health, with the butterfly representing resurrection. Working with fabrics in a wade range of colors and sophisticated designs, Knox is expressing her identity through personal symbolism and imagery. For example, in including fabrics with identifiable African patterns, she is not only recognizing her ancestry, but honoring her heritage.

Figure 4. Face it, 2003, by Anita Knox. Photograph courtesy of Anita Knox.

Art is still also an instrument to show and preserve the traditions, history, heroes, and culture that conforms the identity of a group. This phenomenon is visible in the United States, mostly in the cities of California and Texas, where the Latino population is large and artists from this ethnicity create street murals. Yet these artists have sometimes been criticized on the ground that mural painting is no longer original after the genre was so successfully developed by the Mexican muralists of the 20th century. On this issue, Juarez (1997, p. 67) noted the following:

It is very hard to judge. The quality of murals as ‘art has been questioned more often than their authenticity of expression. […] Too often, the spokesmen of the official ‘art world conveniently stereotype murals as folklore, as protest art, and as minority art, poor art for poor people, in order to dismiss them from serious consideration.

Influenced by geographical or historical circumstances, art is a way to know the world and its people, to exhibit personal life, to create personal symbolism, to show identity or search for one. Even more, art can induce such a reaction in the viewer that could potentially make a social change when art is confrontational wit the society in power.

Art: A quest for identity

In my own case, modeling the faces of Amerindians in clay, while having a Eurocentric art education, was a way to rescue not only the images of my ancestors, but their voices in an attempt to find my own voice. The search for my identity continued when I moved to the UnitedStates and was, in fact, exacerbated by a new set of social rules. As an immigrant, I found myself already classified by society, portrayed as a stereotype that I did not recognize as mine. At that time, through sculpture, drawing, pottery, and writing (e.g., Toledo, 1993, 1996, 1997), I expressed my feelings of living in between two cultures—the one I had left and the one I wanted to became a part of, without losing my identity.

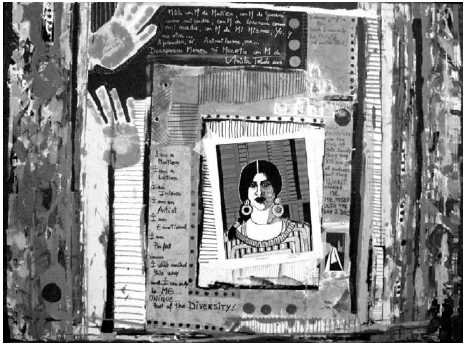

With the letter M (Figure 5) shows through multimedia expressions (painting, drawing, collage, and writing) a redefinition of identity after seventeen years of living in the United States. The `prosa is written in English I define myself in the United States, but it switches unconsciously to Spanish after writing my name and talking about my parents:

I am a Mestiza, I am a Latina, I am Intense, I am an Artist, I am Emotional, I am Perfect, ´cause I was created this way and I can only be Me…UNIQUE…part of the DIVERSITY! PREJUDICES are the Soul of this society, they may kill me of Sadness, but they WONT change ME…ME, Myself, until the day I Die! Mirta, con M de Mestiza, con M de Guaraní, como mi padre, con M de Leonesa, como mi madre, con M de Mi Misma, Yo, y no la otra… Aprender, sí. Asimilarme, no…Desaparecer Menos, ni Muerta, con M de Mirta Toledo

Figure 5. With the letter M, 2005, by Mirta Toledo.

Immersed in a multicultural society (with a dominant monocultural point of view as a measure of everything), I was confronted with issues like my own race. Terms such as purity (as used to define the race of a persons ancestors) and mixed (applied to people who have more than one racial background) became familiar to me.

It was because of these apparently opposite concepts (and the underlying connotation that being the product of mixed-race parents somehow creates a kind of confused human being, with no clear sense of identity) that the idea of Pure Diversity became the soul of my body of work in the earliest 1990s and continues until today.

That quest for identity began by exploring the racial and cultural diversity within my family, celebrating Guaraní and Spaniard cultures, and how I was empowered by my parents cultural differences.

Conclusions

Like the human race, art has multiple faces. Since prehistoric times, every culture developed its own definitions, set of rules, and canons to create and evaluate their art. If one looks at the diversity of expressions in art history, accepting that all cultures are of equal worth, one will be enriched by the different ways in which human nature expresses itself and transcends in time.

Despite the unprecedented power of the mass media to reach the entire world and impose the ideas of beauty, aesthetics, and moral values that are the cultural prototypes of a dominant society, human nature is diverse and creative. Therefore, it may be more realistic to view any expression of art with cultural relativism in mind.

References

1. Acosta Vivas, E. Arte rupestre del Cerro Colorado (Córdoba, Argentina). Retrieved March 18, 2004, from http://rupestreweb.tripod.com/colorado.html [ Links ]

2. Anonymous. Popol-Vuh. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Lozada, (1973). [ Links ]

3. Barone, O. Diálogos Borges-Sábato. BuenosAires, Argentina: EUDEBA, (1996). [ Links ]

4. Collection, The. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, (2002). Retrieved March 18, 2004, from http://moma.org/collection/depts/prints_books/blowups/prints_books_025.html, [ Links ]

5. Chastel, A. French art: Prehistory to the middle ages. Paris, France: Flammarion, (1994). [ Links ]

6. Eco, U. Obra Abierta. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Planeta-Agostini, (1992). [ Links ]

7. Gray, J. E., II. My forefathers. Retrieved September 24, 2007, from http://www.wordsmith47.com/Myforefathers [ Links ]

8. Jiménez, J. Teoría del Arte. Madrid, Spain: Tecnos/Alianza, (2002). [ Links ]

9. Juárez, M. Colors on desert walls: The murals of El Paso. El Paso, Texas: Western Press, (1997). [ Links ]

10. LeFalle-Collins, L and Goldman, S. In the Spirit of Resistance. African-American Modernists and the Mexican Muralist School. New York: American Federation of Arts, (1996). [ Links ]

11. López, A. Paredes parlantes. Austin, Texas: Arriba News, Arts and Culture, (2001). [ Links ]

12. Mohen, J.-P. Prehistoric art. Paris, France: Pierre Terrail, (2002). [ Links ]

13. Oliveras, E. Hermetismo y ambigüedad en el arte contemporáneo. Revista de Cine, 9, (2001), 35-37. [ Links ]

14. Oliveras, E. Estética. La cuestión del arte. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Emece, (2007). [ Links ]

15. Ortega y Gasset, J. La deshumanización del arte y otros ensayos de estética. Madrid, Spain: Ediciones de la Revista de Occidente, (1976). [ Links ]

16. Roach, S. About quilts: An overview, (1992). Retrieved October 23, 2007, from http://www.louisianafolklife.org/quilts/about_quilts.shtm#history [ Links ]

17. Serrano de Haro, A. Mujeres en el arte: Espejo y realidad. Barcelona, Spain: Plaza & Janés, (2000). [ Links ]

18. Tedlock, D. Popol Vuh: The definitive edition of the Mayan book of the dawn of life and the glories of gods and kings. New York: Touchstone, (1996). [ Links ]

19. Toledo, M. La semilla elemental. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Vinciguerra, (1993). [ Links ]

20. Toledo, M. Dulce de leche. Madrid, Spain: Torremozas, (1996). [ Links ]

21. Toledo, M. Un siglo después. In VIII Premio Ana María Matute: Baucis y Filemón (pp. 101-106). Madrid, Spain: Torremozas, (1996). [ Links ]

22. Toledo, M. In between. In K. S. Leonard (Ed.), Cruel fictions, cruel realities (pp. 109-118). Pittsburg, Pennsylvania: Latin American Literary Review Press, (1997). [ Links ]

23. Walker Art Center. Interactivity art activity, (1998). Retrieved March 20, 2004, from http://www.walkerart.org/archive/9/B7838DD567B1D4546174.htm [ Links ]

24. Westheim, P. Ideas fundamentales del arte prehispánico en México. México, México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, (1957). [ Links ]

25. White, J. E. The beauty of black art. Time, 144, (1994), 72-73. [ Links ]

26. Whitney Museum. Black male. Representations of masculinity in contemporary American art. New York, NY: Whitney Museum, (1994). [ Links ]

27. Witcombe, C. L. C. E. Venus of Willendorf: Earth mother-mother goddess. In Women in prehistory: The Venus of Willendorf, (2000). Retrieved on March 18, 2004, from http://witcombe.sbc.edu/willendorf/willendorfdiscovery.html [ Links ]