Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana

versão impressa ISSN 1794-4724versão On-line ISSN 2145-4515

Av. Psicol. Latinoam. v.26 n.2 Bogotá jul./dez. 2008

A psychological treatment programme for traumatised ex military personnel in the UK

Un programa de tratamiento psicológico para personal exmilitar traumatizado en el Reino Unido

John Gale*

Elefftherios Saftis*

Inmaculada Vidaña Márquez*

Beatriz Sánchez España*

* Community Housing and Therapy, United Kingdom. Correspondence to: John Gale, Community Housing and Therapy, 24/5-6 The Coda Centre, 189 Munster Road, London SW6 6AW, United Kingdom. E-mail: jg@cht.org.uk

Fecha de recepción: junio de 2008

Fecha de aceptación: agosto de 2008

Abstract

A large proportion of homeless people in the UK are former members of the armed services and suffer from a mental illness. In fact, homelessness itself can be considered a symptom or manifestation of other underlying psychological difficulties. For these reasons Community Housing and Therapy (CHT) considers that providing psychological therapies to treat the homeless population is a more effective way of tackling the problem of homelessness, as it addresses the roots of the problem. This approach is one which is beginning to be recognised by leading agencies in the field. At the same time, the provision of psychological therapies for symptoms such as depression and anxiety has become accepted through the Department of Health's (DoH) Increased Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) initiative. Depression is the most common psychiatric disorder that homeless people suffer and it is well documented that psychological treatments for depression can be extremely effective. As well as approaching homelessness from the angle of psychological therapies, CHT in its work with the ex-service community has become increasingly aware that there are a large number of non statutory homeless that do not get the same attention as rough sleepers.

Key words: homelessness; ex-military; psychotherapy; therapeutic communities; treatment.

Resumen

Una gran proporción de personas sin hogar en el Reino Unido corresponde a ex-miembros de las fuerzas armadas, quienes sufren además de enfermedades mentales. El hecho de no tener un hogar se puede, en sí mismo, considerar como un síntoma o una manifestación de otras dificultades psicológicas inherentes. Por esta razon, Community Housing and Therapy considera que dando terapias psicológicas para tratar el hecho de no tener un hogar es una forma más efectiva de enfocar el problema, debido a que trata su raíz. Este enfoque se está empezando a reconocer por agencias líderes en el área en el Reino Unido. Al mismo tiempo, la provisión de terapias psicológicas para tratar síntomas tales como la depresión y la ansiedad ha sido aceptada por la iniciativa del Departamento de la Salud (DoH) denominada Increased Access to Psychological Therapies' (IAPT). La depresión es el desorden psiquiátrico más común que la población sin techo sufre, pero también está documentado que los tratamientos para la depresión pueden ser muy efectivos. Además de enfocar el problema de la población sin hogar desde un punto de vista psicológico, CHT en su trabajo con la comunidad de ex-militares se ha conscienciado cada vez más de que hay un gran número de personas sin hogar que no están reconocidas por las autoridades y que no reciben la misma atención que las personas efectivamente clasificadas como sin hogar.

Palabras clave: población sin hogar; exmilitares; psicoterapia; comunidades terapéuticas; tratamiento.

Introduction

Ex-service men and women can find it difficult to adjust to civilian life. Those with psychological difficulties often develop symptoms including alcohol or drug abuse and homelessness, and need support and assistance. According to the Mental Health Foundation, there are five million veterans (with eight million dependants) in the UK, along with around 180,000 serving personnel. Although only a minority of serving personnel and veterans experience mental health problems, they still form a large group of people.

The mental health problems experienced by military personnel are the same as the general population, although experiences during service and the transition to civilian life mean that their mental ill health may be triggered by different factors. Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety and substance abuse affect a significant minority of service personnel and veterans. There has been little research into mental health in the UK armed forces compared to the United States. However, various UK studies have indicated links between active service and mental health problems:

Homelessness

Homelessness in London was a problem that escalated to a very large proportion in the 1990's. Efforts by the Government's Rough Sleepers' Unit decreased the number of people sleeping rough in London by over 50% from 621 in 1998 to 264 in 2001 (Homeless Link, 2002). The Department of Health strategy has been effective in targeting the most entrenched rough sleepers with severe mental illness and has drastically reduced the numbers (CLG, 2008). It is estimated that 30%-50% of the homeless population suffer from some form of mental illness (Homeless Link, 2006). Increased attention has been given to the value of psychological therapies for the homeless. The underlying causes of homelessness, and its associated problems such as substance misuse, depression and anti-social behaviour should be addressed as people will continue to become homeless even when adequate provision is offered to them.

The Homeless Link document Ending Homelessness: from Vision to Action (2006) identifies three key strategic elements to end homelessness. These are (1) prevention (2) support and (3) accommodation.

Homelessness and the ex-service community

Current estimates of homelessness within the exservice population are at approximately 6% (Rhodes et al, 2006). This percentage is similar to the one reported by the CLG (Communities and Local Government, 2008) which estimated that the percentage of ex-service rough sleepers is 5%. There remains a very high number of single non statutory ex-service homeless in London on any given day, current projections estimate up to 1,100 individuals. The term non statutory homeless refers to those to whom the state does not consider it has a duty to house, either because they are deemed intentionally homeless or because they are not viewed a priority. It includes the single homeless' many of whom are young people of both sexes (Rhodes et al, 2006).

In their report Rhodes et al. (2006) identified that the main difficulties that ex-service personnel face are psychological disorders, drug and alcohol dependency and physical illness. The report from The Royal British Legion (2006) based on the findings of twelve months of research concluded that the main difficulties in the younger ex-service population (16-44 years) are mental health difficulties, particularly depression, unemployment, a lack of transferable skills and few opportunities for training for work. According to the Centre for Military Health Research at King's College London, even though there is good evidence for the benefit of psychological treatments for depression and PTSD, only a minority of ex-service individuals will receive this treatment (Iversen et al., 2005a, 2005b).

Homelessness and psychotherapy

In an analysis by St Mungo's it was suggested that the main mental health disorder that the homeless population faces is depression (St Mungo's 2006). Recently a World Health Organisation study (World Health Organization, 2008) concluded that the impact of depression on a person's suffering was 50% more serious than angina, asthma, diabetes and arthritis.

The Improving Access to Psychological Therapies Commissioning Toolkit (Department of Health, 2008) published by the Department of Health suggests that commissioning psychological therapies can improve people's health and well-being, including those with long-term conditions, leading to savings for the wider health economy and more cost-efficient mental health care pathways. The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) recognises psychological therapies as effective and safe treatments, both in the short term, and for preventing relapse in the long term.

Although health authorities claim to look after former soldiers, most GPs and consultants have little or no experience of this area, and many ex service personnel drop out of treatment programmes because they believe staff cannot understand the traumas they have been through. Additionally, there is a scarcity of statutory provision of psychological services available. Dr Andrew McCulloch Chief Executive of the Mental Health Foundation has commented that, people suffering from post traumatic stress disorder triggered by military conflict have specific needs that require specific services that are just not available on the National Health Service (NHS). Outside the NHS, the charity Combat Stress provides specialist inpatient and outpatient mental health care for veterans while other organisations, such as Community Housing and Therapy (CHT), provide residential psychotherapy and psychosocial services for ex-service personnel.

Community Housing and Therapy (CHT)

CHT is a registered charity that runs nine small therapeutic households for the severely mentally ill and the homeless, with a staff team of approximately forty five psychologists and psychotherapists, and a comprehensive training programme in group therapy for therapeutic community practitioners, accredited by Middlesex University. Since its foundation CHT has developed a particular therapeutic community style under the influence of the Lacanian reworking of psychoanalytic theory (Gale, 2000; Gale, 2008; Gale and Sanchez España, 2008) and a review of its philosophical foundations (Sanchez, 2004; Gale and Sanchez, 2005b; Paget, 2000). While it is frequently asserted that the therapeutic community rests on psychoanalysis, there has been very little discussion in the literature of the fundamental place of language in the treatment (Hinshelwood, 1999; Gale, 2000). And yet, like psychoanalysis, a therapeutic community methodology, particularly in its application to psychiatric patients, rests profoundly on speech. A therapeutic community, as other communities, is held together in some way by language and it is in the community that the thread of speech comes alive. It is not just that the language of this particular community is technical, or specialised in some sense. Of course there is a degree of specialised language in any subgroup, and therapeutic communities and even particular therapeutic communities within one organisation, are no exception. But the relationship which each member has to the meaning of his or her experience, and to the life of the community and its history, are all connected to his or her participation in language. Difficulty lies in the meaning that the words have for the patient and the connections that he or she makes between thoughts and words. Today community-based therapeutic communities have the potential to be at the forefront of provision in terms of putting users at the centre of treatment and listening to their views. The treatment environment in a therapeutic community is one which values patients' experiences to a unique degree. Through close partnership working, the integration of psychological and psychiatric approaches, as well as psychotherapy in its group analytic and individual psychodynamic forms, is possible. The potential for cooperation and multidisciplinary care planning and review, involving the patient, other users, psychiatrist, psychotherapist, social worker, the family and other key workers, is at its optimal in non-residential or small residential settings. Furthermore, because of the intensity of the programme, it is possible to monitor the effects of medication and through regular reviews manage change (Gale and Sanchez, 2005a).

About 100 patients each year live in CHT's communities. CHT achieves an average annual occupancy level of 90.7%. Most of those referred suffer from schizophrenia, and remain in residence for an average of two years (ibid).

Therapeutic community treatment of traumatised soldiers: the historical context

Working with psychologically disturbed former soldiers, sailors and airmen is, in a sense a return to one of the key moments in the development of TCs (Gale et al., 2006). It was during the Second World War in two military hospitals, Northfield Hospital in Birmingham and Mill Hill Hospital, to which part of the Maudsley Hospital had been evacuated at the outbreak of the war. It was at Northfields and Mill Hill that TC concepts were first applied in a psychiatric setting (Harrison 1999). Four leading psychoanalysts, Wilfred Bion, Sigmund Foulkes, Tom Main and Maxwell Jones -who were to have an enormous influence on the TC movement as a whole- all worked in these military hospitals. In fact their influence went beyond the TC movement. Bion, whom David Kennard has described as one of the most influential post war contributors to psychoanalytic theory was later to develop his theory of group basic assumptions at the Tavistock Clinic and strong links were formed, during the Second World War between the Tavistock Clinic and the Army (Shephard, 2002; Kennard, 1998). This cooperation between psychiatry and the Army perhaps came to fruition in Bion's development of the leaderless group' as a technique in the process of officer selection. John Bowlby saw this as a crucial intervention which had the effect, additionally, of introducing a degree of democracy into the military hierarchy (Shephard, 2002). Foulkes went on to form the Institute of Group Analysis (IGA) and Tom Main became the director of the Cassel Hospital (Kennard 1998). As a result psychoanalysis has justifiably been described as the founding idea of TCs (Hinshelwood, 1999). However, at Northfield Hospital there was already a degree of eclecticism which amounted to something of a hotch potch of psychoanalyisis, group dynamics and dramatherapy, as well as what we might now recognise as cognitive behavioural therapy cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) (Shephard, 2002).

This paper is a case study in the development of an innovative TC project over a three year period and is significantly relevant to our contemporary situation, as it confronts the psychological effects of combat, military training and culture on servicemen and women. It records successful outcomes over the three year period and details of the period 2006-07.

Home Base

In 1997 CHT was approached by The Homeless Fund to set up a dispersed therapeutic community for homeless ex service personnel. A pilot was established with six beds, funded by the National Lottery Charities Board. Following the pilot year the project has developed to 21 beds and is funded principally by annual grants from The Royal British Legion, the Army Benevolent Fund and other charitable trusts, together with statutory funding from Supporting People. Small additional grants are also received from Seafarers UK and the RAF Benevolent Fund (NCVO, 2006). A report by NCVO's Performance Hub, identified the funding-funded relationship between The Royal British Legion and CHT as one of six examples of best practice which illustrated how funders and funded organisations can work together. It summarised the benefits from the funding-funded relationship as follows:

Home Base has a number of original features. It has kept the Ministry of Defence (MoD) and ex service charities on board, while managing to maintain the distance from the military necessary for effective therapeutic interventions and operational independence. It is an interagency initiative which integrates a psychoanalytic perspective in the treatment of homelessness and its habitual symptoms of alcohol and substance abuse. It has also developed a therapeutic community treatment which successfully bridges the gap between psychotherapy and practical skills training for work.

Home Base was formed to provide psychotherapy, rehabilitation and accommodation within the psychosocial environment of a therapeutic community. It does this through partnerships with registered social landlords (RSLs) and other organisations. Additionally, Project Compass / Business Action on Homelessness (part of Business in the Community) provide training and employment opportunities for its service users. Since its inception Home Base has been an active collaborator in the Ex-Service Action Group on Homelessness and has also developed strong links with the Confederation of British Service and Ex-Service Organisations, the MoD and the Department of Communities and Local Government in order to provide the best possible support to venerable members of the exservice community.

Currently Home Base provides 21 places and outcomes are measured through continuous data collection analysis and individual assessments of clients. CHT has commissioned research fellows from the universities of Manchester and Nottingham on quantitative and qualitative research programmes and is about to enter into a partnership with Southampton University the Centre for Social Work Research at the University of East London/ Tavistock Clinic, to evaluate the effectiveness of the programme.

Treatment schedule

Individual sessions

In weekly individual psychotherapy sessions clients mental and emotional disorders are treated through the use of psychological techniques to encourage communication of conflicts and insight into problems, with the goal being relief of symptoms, change in behaviour leading to improved social and vocational functioning, and personality growth. This is achieved by helping the patient attain insight into the repressed conflicts which are the source of difficulty. Through the use of CBT the patient's dysfunctional behaviour is changed, using positive reinforcement, developing increased self-efficacy and more realistic and positive attitudes.

Figure 1. The treatment path of clients.

Group sessions

In weekly group psychotherapy sessions clients are guided by a therapist to confront their personal problems together. The interaction among clients is an integral part of the therapeutic process. Group therapy focuses on interpersonal interactions, so relationship problems can be addressed. The aim of group psychotherapy is to help with solving the emotional difficulties and to encourage the personal development of the participants in the group.

Members of the group share with others the personal issues which they are facing in adjusting to civilian life. Here participants can talk about event they were involved in during their time in the armed forces, during the time they were homeless or even during the last week. By sharing his/her feelings and thoughts about what has happened to them, clients can give each other feedback, encouragement, support or criticism. Members in the group learn to feel less alone with their problems and the group can become a source of support and strength in times of stress for the participant and a laboratory for new behaviours.

Monthly meal

The community get together to share a meal together each month. This is an important event in the life of the community and provides a setting in which clients can develop relationships and social skills. Often patterns of behaviour appear that indicate the difficulties clients have in forming or maintaining relationships. Later, staff can draw on their exposure to clients in this social setting, to help a client reflect on his experiences of family life – particularly, looking after others and being looked after in childhood. The aims of this kind of social event are manifold, ranging from community building to provoking reflection on relationships and nurturing strategies.

Monthly house meeting

The monthly house meetings focus mainly on the day to day life of the community. The aim is to help clients engage with the community in practical ways and increase the level of responsibility they take for their life.

Move on group

Tenancy breakdown is common amongst homeless people. These groups focus on helpings clients, from the beginning of their placement, to think about the long term; about moving to permanent accommodation and how to sustain tenancies. It is a forum in which mutual support is given and strategies are shared in order to find suitable accommodation and sustain it.

Employment and training interventions

Soon after admission clients are assessed for work and their training needs identified. In most cases a referral is made to weekly sessions at Project Compass and the Transitional Spaces Project. Here work training opportunities are provided.

Social enterprise

A horticultural therapy/training project was developed by Home Base in November 2007. A grant of £9,950 was received by the CLG as part of their hostels capital improvement programme (HCIP). This aims at helping clients learn the skills to run their own business, cultivating fruit and vegetables and selling it in a local market.

Inter agency work

Home Base has strong links with other agencies. This is due to the co-operation which exists within the ex-service community. In addition, it has also developed relationships with other organisations such as Homeless Link.

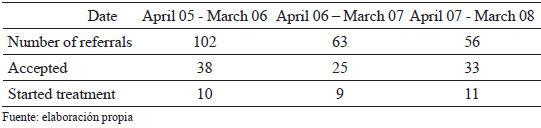

Table 1

Referring agencies

Table 2

Outcome of referrals

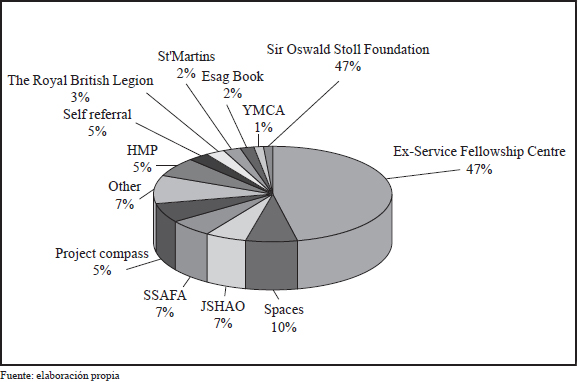

Figure 2. Referrals April 2005 – March 2006.

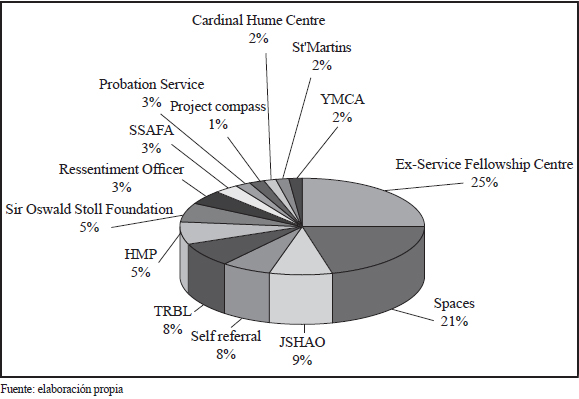

Figure 3. Referrals April 2006 – March 2007.

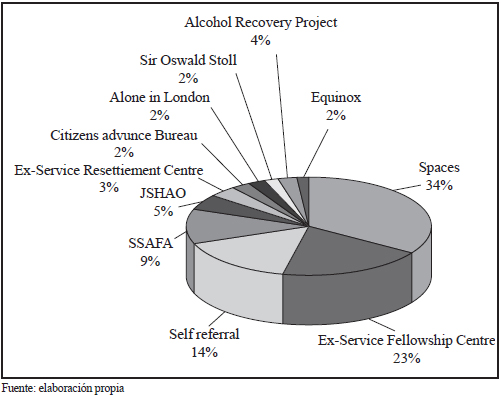

Figure 4. Referrals April 2007 – March 2008.

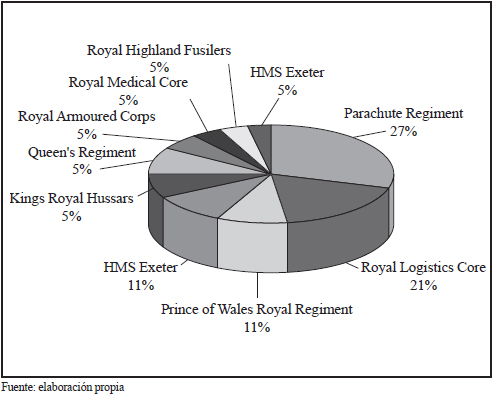

Figure 5. Former service units April 2007 – March 2008.

Convictions prior to admission

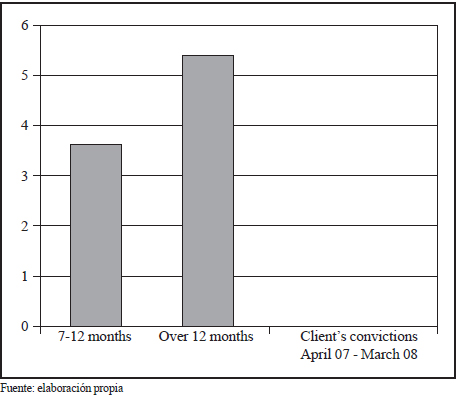

Figure 6. Client's convictions April 2007 – March 2008.

Diagnoses

Over the last three years we see a marked increase in those entering the programme with depression, PD and alcohol addiction. Whereas those with anxiety have decreased. This indicates a general trend towards referrals with more severe disorders.

Figure 7. Comparison of clients diagnoses over the past three years. Relating to the period April 05 – March 08.

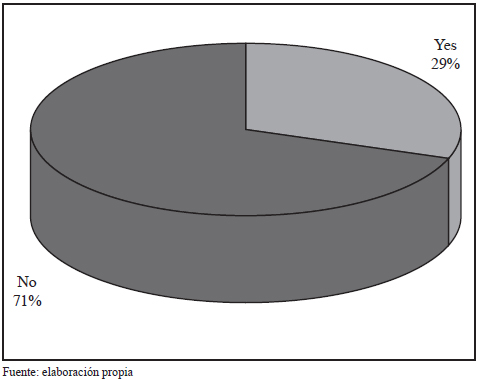

Previous contact with psychological services

The majority of clients when entering treatment have not received any previous psychological treatment. The minority that have had some form of treatment will usually have received treatment for an addiction.

Figure 8. Clients previous contact with specialist service April 2007 – March 2008.

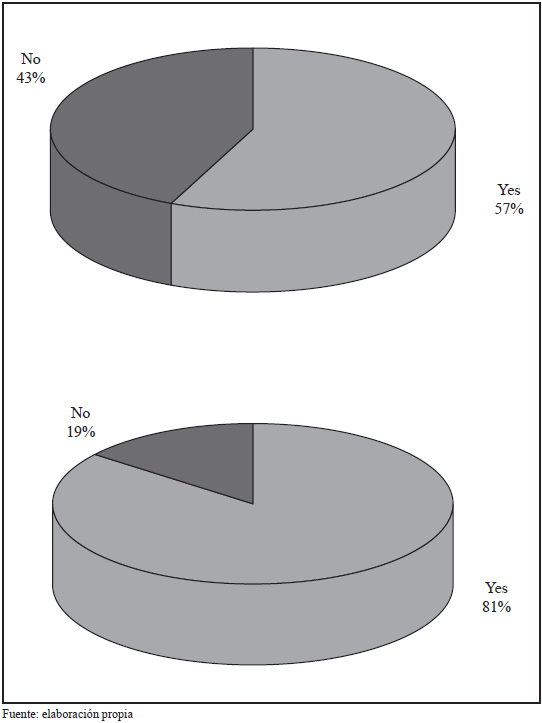

Training and employment

The majority of clients are in need of training in order to be able to gain, secure and sustain employment. The majority of clients are able to gain employment after approximately one year in the community.

Most others of move this within 18 months.

Figure 9. Client employment and training for employment April 2007 – March 2008.

Placement length

The average length of stay is 20 months. Length of stay depends on treatment progress and the availability of move on accommodation.

Discharge and move on

The majority of clients that leave the community move to independent accommodation successfully. Although four out of 11 people did not complete treatment we still achieved above the Supporting People criteria for success.

Figure 10. Client move on April 2007 – March 2008.

Table 3

Case studies of two clients

Conclusion

Despite common attributes, existing therapeutic communities have various origins. In the UK, while those that flourished in hospitals are largely gone, care in the community has meant that new smaller therapeutic households have become an integral part of the provision for the mentally ill in the community. The democratic and psychoanalytically-orientated communities such as those run by Community Housing and Therapy lay emphasis on the tension between permanence and temporality in meaning. Full speech (parole pleine) is the way in which patients enter into a shared world and make sense of their experiences from a perspective of a common understanding. It is a community made up of staff and patients, and the struggle to articulate meaning is shared by all through involvement. This involvement is focused primarily on continually interpreting the world despite the onslaught of unconscious processes, particularly those projections associated with foreclosure. Thus the therapeutic community is a hermeneutic project, in which perceptible things and rationality are viewed as just a small part of the picture but a part which points patients towards the truth of the unconscious. Fundamentally this existential project has a deep spiritual resonance and the response of veterans to the demands of everyday living serve as a metaphor for states of mind as, for example, homelessness.

Over the last year we have seen people with more severe problems being referred to Home Base, particularly those with depression, a personality disorder and addiction. 45% of these had a conviction prior to referral, while very few had had any contact with specialist services prior to admission. The increased level of morbidity contributed to a slightly longer stay than in previous years and length of stay averaged at 20 months. However, 81% of clients completed a vocational training course and 57% gained full time employment while on the programme. Of those discharged in the period, 64% completed treatment successfully.

References

1. Adby, M. & Mayall, H. Funding better performance: Supporting performance improvement through the funding relationship. London: The Performance Hub, (2006). [ Links ]

2. British Royal Legion. Annual Report & Accounts, (2006). Available in: http://www.britishlegion.org.uk [ Links ]

3. Communities and Local Government. Rough sleeping 10 years on: from the streets to independent living and opportunity. Discussion paper. Wetherby, UK: Communities and Local Government Publications, (2008). [ Links ]

4. Department of Health. Improving access to psychological therapies (IAPT) commissioning toolkit. London: Department of Health Publications, (2008). [ Links ]

5. Gale, J. The dwelling place of meaning. In: S. Tucker (Ed.), A therapeutic community approach to care in the community. Dialogue and dwelling (pp. 35-54). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, (2000). [ Links ]

6. Gale, J. & Sanchez, B. Reflections on the treatment of psychosis in therapeutic communities. Therapeutic Communities, 26 (4), (2005a), 433-447. [ Links ]

7. Gale, J. & Sanchez, B. The meaning and function of silence in psychotherapy with particular reference to a therapeutic community treatment programme. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 19 (3), (2005b), 205-220. [ Links ]

8. Gale, J., Vidaña Márquez, I., Al-Kudhairy, N., Saftis, E., Knotley, K., & Azua, V. A three-year study of the treatment of psychological disturbed homeless ex-military personnel in a therapeutic community. Therapeutic Communities, 27 (4), (2006), 503-521. [ Links ]

9. Gale, J. Exegesis, truth and tradition: A hermeneutic approach to psychosis. In J. Gale, A. Realpe & E. Pedriali (Eds.), Therapeutic Communities for Psychosis: Philosophy, history and clinical practice (pp. 38-51). London: Routledge, (2008). [ Links ]

10. Gale, J. and Sánchez España, B. Evidence for the effectiveness of therapeutic community treatment of the psychoses. In: J. Gale, A. Realpe & E. Pedriali (Eds.), Therapeutic Communities for Psychosis: Philosophy, history and clinical practice (pp. 255-265). London: Routledge, (2008). [ Links ]

11. Harrison, T. Bion, Rickman, Foulkes and the Northfield Experiments. Advancing on a different front. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, (1999). [ Links ]

12. Hinshelwood, R. D. Psychoanalytic origins and today's work: The Cassel heritage. In: P. Campling & R. Haigh (Eds.), Therapeutic Communities: Past Present and Future (pp. 39-49). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, (1999). [ Links ]

13. Homeless Link. An overview of homelessness in London. London: Homeless Link, (2002). [ Links ]

14. Homeless Link. Ending homelessness: From vision to action. London: Homeless Link, (2006). [ Links ]

15. Iversen, A., Dyson, C., Smith, N., Greenberg, N., Walwyn, R., Unwin, C., Hull, L., Hotopf, M., Dandeker, C., Ross, J., Wessely, S. Goodbye and good luck: the mental health needs and treatment experiences of British ex-service personnel. British Journal of Psychiatry, 186, (2005a), 480-486. [ Links ]

16. Iversen, A., Nikolaou, V., Greenberg, N., Unwin, C., Hull, L., Hotopf, M., Dandeker, C., Ross, J., Wessely, S. What happens to British veterans when they leave the armed forces?. European Journal of Public Health, 15 (2), (2005b), 175-184. [ Links ]

17. Kennard, D. An introduction to therapeutic communities. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, (1998). [ Links ]

18. Paget, S. Delusions as discourse in a therapeutic community. Therapeutic Communities, 21 (4), (2000), 253-259. [ Links ]

19. Rhodes, D., Pleace, N., & Fitzpatrick, S. The numbers and characteristics of homeless ex-service people in London: A review of the existing statistical data. York, UK: Centre for Housing Policy, University of York, (2006). [ Links ]

20. Sanchez, B. Understanding the psychotic mental structure from a Lacanian point of view and a dialogical treatment in a therapeutic community. Therapeutic Communities, 25 (4), (2004), 253-260. [ Links ]

21. Shephard, B. A war of nerves: Soldiers and psychiatrists 1914-1994. London: Pimlico, (2002). [ Links ]

22. St Mungo's. Homeless Statistics, (2006). Can be found at: http://www.mungos.org/homelessness/facts/homelessness_statistics/ [ Links ]

23. World Health Organization. World Health Statistics Report, (2008). Available in: http://www.who.int/whosis/whostat/2008/en/index.html [ Links ]