Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana

versión impresa ISSN 1794-4724

Av. Psicol. Latinoam. vol.32 no.2 Bogotá may./ago. 2014

New Scenarios of Training in Psychology in Brazil

Nuevos escenarios de formación en Psicología en Brasil

Novos cenários de formação em psicologia no Brasil

João Paulo Macedo

Universidade Federal do Piauí

Magda Dimenstein

Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte

Adrielly Pereira de Sousa

Davi Magalhães Carvalho

Mayara Alves Magalhães

Francisca Maira Silva de Sousa

Universidade Federal do Piauí

* João Paulo Macedo, Psicologia, UFPI; Adrielly Pereira de Sousa, Psicologia, UFPI; Davi Magalhães Carvalho, Psicologia, UFPI; Mayara Alves Magalhães, Psicologia, UFPI; Francisca Maira Silva de Sousa, Psicologia, UFPI; Magda Dimenstein Psicologia, UFRN . Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to: Universidade Federal do Piauí, Campus Ministro Reis Velloso, Departamento de Psicologia. Av. São Sebastião, 2819. Reis Veloso. 64202020 - Parnaíba, PI - Brasil.

E-mail: jpmacedo@ufpi.edu.br

Doi: dx.doi.org/10.12804/apl32.2.2014.10

Received: September 3, 2013

Accepted: March 7, 2014

Abstract

The training in psychology in Brazil undergoes transformations with the expansion of the higher educational sector. On the one hand there is a growing number of courses in psychology at work in the interior regions of the country. On the other, there is a growing incorporation of educational institutions by foreign groups. Thus. the objective of this study reflects on the scenarios of internalization and internationalization of psychology courses, focusing on the challenges to the formation of the Brazilian psychologists. This is a descriptive exploratory study, in which the information for data analysis was recovered in official databases on higher education in Brazil. We believe that this context sets new scenarios and challenges for the training of psychologists, as it repositions the profession in our country, before centered in urban centers, and requires that curricula, including internationalized courses, meet local specificities (spatial, social and symbolic) that permeate Brazilian reality.

Keywords: Psychology, higher education, professional training

Resumen

La formación en Psicología en Brasil pasa por transformaciones, debido a la expansión del sector de enseñanza superior. Por un lado, se observa un crecimiento de programas de Psicología en las regiones del interior del país. Por otro lado, se observa la incorporación cada vez más frecuente de instituciones educativas por parte de grupos extranjeros. Se pretende con este estudio reflexionar sobre los escenarios de internalización e internacionalización de los programas de Psicología enfocando en los desafíos para la formación del psicólogo brasileño. Este es un estudio descriptivo exploratorio en el que la información para el análisis de los datos se obtuvo de bases de datos sobre educación superior en Brasil. Creemos que este es un contexto que presenta nuevos escenarios y desafíos para la formación de los psicólogos, reposicionando la profesión en nuestro país, antes centralizada en centros urbanos, y requiriendo que los currículos, inclusive los de los programas internacionalizados, conozcan las especificidades locales (espacial, social y simbólica) que permean la realidad brasileña.

Palabras clave: Psicología, educación superior, formación profesional

Resumo

A formação em Psicologia no Brasil passa por transformações com a expansão do setor do ensino superior. Por um lado, há um número crescente de cursos em Psicologia nas regiões do interior do país. Por outro lado, há uma incorporação crescente de instituições educativas por grupos estrangeiros. Assim, o objetivo deste estudo reflete sobre os cenários de internalização e internacionalização dos cursos de Psicologia, focando nos desafios da formação dos psicólogos brasileiros. Este é um estudo descritivo-exploratório, no qual a informação para a análise dos dados foi recuperada em bases de dados oficiais sobre o ensino superior no Brasil. Acreditamos que este contexto estabelece novos cenários e desafios para a formação de psicólogos, reposicionando a profissão em nosso país, antes centralizada em centros urbanos, e requere que os currículos, incluindo cursos internacionalizados, conheçam as especificidades locais (espaciais, sociais e simbólicas) que permeiam a realidade brasileira.

Palavras-chave: Psicologia, ensino superior, formação profissional

The formation of psychologists in Brazil has gone through many transformations over the past two decades. Among the major changes, citing the approval in 2004 of the National Curriculum Guidelines (NCG) for Undergraduate Courses of Psychology based on the Law of Guidelines and Basis of National Education (LGB), from 1996. The establishment of this new legal framework in Brazilian higher education led to the replacement of the concept of minimum curriculum of undergraduate courses from the curriculum guidelines. While the minimum curriculum established uniformity between courses, prefixing the content and subjects transmitted, workload and mandatory internships, curriculum guidelines shaped the higher education as a continuous and ongoing process, so the future graduate can face the challenges of the rapid changes in society, the labor market and conditions of professional practice.

In the case of psychology, the debate on the replacement of the first curriculum, organized on the basis of minimum curriculum, to unfold in discussions about the creation of NCG, went on for 30 years. Soon after the approval of the first curriculum set by Opinion 403/1962, ofthe Federal Board of Education, emerged the first criticisms and some proposals for change. Rocha Jr. (1999), remarks that there were at least two moments of intense discussion on the topic: the first between 1970 and 1980, without much success, only resulted in adding subjects; the second, between 1990 and 2000, which was permeated by the debate about the role and social commitment ofthe professional, as well as around the requirements of redefinition of roles and functions in the professional market in both the public and the private. This resulted in strong dialogue between authorities and bodies representing the profession on new scenarios for the Brazilian psychologist and, consequently, intensified discussions about new horizons for their academic and professional formation.

The main points raised in this debate were about the character overly technical and fragmentary in acquiring knowledge, incorporation of knowledge based on foreign sources and decontextualized applications, in addition to poor articulation between theory and practice, little emphasis on research and knowledge production as well as lack of clarity around ethics and politics of Brazilian reality (CFP, 1988, 1994; Bock, 1999; Ferreira Neto, 2011).

After an intense debate to define a new concept of curriculum, the NCG were approved with a proposal of general basic training, with emphasis on a solid education in the basics of the psychological science and other areas of knowledge (biological foundations, philosophical, socio-cultural, etc.); on the development of a critical, reflective and investigative posture, emphasizing interdisciplinarity, in addition to practical training and technical-cientific and respect the multiplicity of theoretical and methodological concepts, originating from different paradigms, different ways of understanding science and the relationship between man and the world, without losing the diversity of practices and contexts of activity, especially in public policy.

The document also put into question the need for getting deeper into ethical issues in the curriculum, in order to constitute a political consciousness of citizenship and commitment to the social reality in which the psychologist is professionally inserted (CNE, 2004).

For Ferreira Neto (2011), the transformations in the training of psychologists were only possible because Psychology courses in Brazil have always had strong links with the profession. The changes in the labor area, over the last three decades, accompanied by critical and reflective experience accumulated during this period, reverberated in the organizations of the courses psychology of our country.

The opening of new scenarios and territoriality for the profession proposed by public policies, particularly in Health, Mental Health and Social Welfare, besides networking with the various sectors of Brazilian society, including social movements, caused psychologists to engage in the movement of health reform and defense of the Unified Health System (SUS); with the movement of antimanicomial fight and defense of the psychiatric reform; with the Unified Social Assistance (SUAS) and people living in poverty and social vulnerability; with the issue of human rights and protection against violence and torture in the prison system; with the defense of the Statute of Children and Adolescents and the issue of reducing the criminal age; to combat violence against the elderly, women and children and other forms of discrimination (gender, racial, sexual, religious, etc.); as well as issues related to violence in traffic and urban mobility problems and land disputes, fight for land; and civil defense actions facing emergency situations or disasters and catastrophes, among others.

The involvement of all these fields diversified greatly in both traditional areas of expertise of psychologists, so far focused largely on clinical activities of liberal model, for the insertion locations in order to no longer restrict the professional only to capital and large urban centers. Among the main criticisms and accumulated experiences, with the inclusion of professional psychologists in the public policies, we highlight the fact that these new fields of practice demand competencies and skills increasingly diverse, especially by meeting with a new clientele (popular classes and populations living in precarious conditions of life); with a kind of institutionalized work, ie, linked mainly to the public sector, therefore with regulations regarding schedules, activities, records, etc.; finally, with the need for interdisciplinary actions and team performances. These are changes that require the need of training for a better balance between the clinical area and other areas, apart from the specific design ofthe expansion of clinical practice previously centered hegemonically in individual and intrapsychic universe of subjects, and this new understanding with the responsibility to consider the social context in which families and individuals find themselves, in order to also ponder the psychosocial processes involved. In this regard, it is expected that the formations in Psychology may establish professional skills and competencies that enhance the know-how of clinical work, combining it with epidemiological perspectives and management of work processes in health, for conducting group activities of health promotion and prevention, empowerment and mobilization of community resources (Ferreira Neto, 2011).

However, besides the transformations around the curriculum, we call attention to a new movement for change that crosses the training of psychologists in our country today: it is the interiorization and internationalization of Psychology courses. Some studies have debated about the recent changes in the profile of the profession and training, especially because we are going through an intense process of expanding the number of psychologists, whose main cause is the actual expansion of higher education. With a growth of over 400% in the total number of psychologists in the last two decades, we get to total of236,100 records (Bastos, Gondim, & Rodrigues, 2010). Therefore, a better distribution of professionals in the various states and regions of the country and strengthening the profession in more inland locations can be seen, changing that idea built in the 1980s - that psychology was a profession regarded as essentially urban. Currently, 48% of psychologists work in the inner cities, highlighting those of medium and small size, while 32% work in the capital cities (Bastos, Gondim, & Rodrigues, 2010).

Regarding training, the reality is not very different. While that is a significant expansion of the number of Psychology courses in major cities and capital cities of Brazil, it is also in the medium and small size cities (Lisboa & Barbosa, 2010; Macedo & Dimenstein, 2011). This has required major changes in the training of Brazilian psychologists, since it has led our science and profession to a different reality from that traditionally seen in big cities, especially because in small cities the living conditions and the social, symbolic and cultural relations, therefore, the processes of subjectivity and identity relations, are not the same as the urban world.

On the other hand, if there are few studies that deal with the interiorization of training, when we refer to the issue of internationalization of higher education and its relationship with courses of Psychology, we realize that this is a virtually unexplored topic in the national literature, except for postgraduate. We know that the process of com-modification of higher education has deepened with the expansion of the private sector, mainly for what it represents in international financial markets, namely target of investment funds in the stock market or stock exchange.

Therefore, we will present both the interiorization process as the internationalization process as mentioned earlier, in the interest of discussing the challenges they impose on the training of psychologists in Brazil. To do so, we will bring the data on higher education, circumscribing the information about the courses of Psychology, based on the information system of the Ministry of Education (http://emec.mec.gov.br/), recovered in the first quarter of 2012.

Expansion and interiorization of the formation of psychologists in Brazil

In Brazil, there are 2,378 higher education institutions (HEIs) being 278 public (11.7%) and 2,100 private (88.3%). As for the academic organization, there are 190 universities (7.9%) and 2,151 other higher education institutions, which can be grouped as universities and colleges (90.45%), and 37 federal institutions of technical education and technology. About the local operation, 826 HEIs are located in capital cities (34.73%) and 1,552 in the inner cities (65.26%). The South and Southeast regions stand out as those in which the process of interiorization of higher education is faster, with 75.1% and 74.1% respectively, while in the North and Northeast the HEIs are concentrated in the capital, 61% and 51.7%. Specifically about the courses, 28577 are distributed in the public sector (30.9%) and private (69.1%), and 10,689 are located in capital cities, and 17,888 in the interior. These courses have a total of 5.5 million students enrolled, and most concentrated enrollments continue in universities (54.3%), followed by schools (31.2%) and university centers (14.5%) (Brazil, 2011). There is, therefore, the supremacy of the private over the public, accompanied by a large number of institutions that prioritize teaching actions, in the case, the colleges, to the detriment of research development and teaching activities in the society (university extension). This picture transforms the clientele into mere consumers of the educational sector, with courses focused on teaching actions only (Martins, 2009).

Another aspect to be highlighted is related to the expansion of the university to the interior locations. In general, we consider this as a breakthrough in the political of deconcentration and democratization of higher education in Brazil. The point is that there is little difference in the ratio between the number of students enrolled in capital (2590888 students / 47.54%) and in the country (2858232 students / 52.45%), indicating that access to higher education is still limited for most Brazilians (Brasil, 2011). On the other hand, most HEIs located in the interior are linked to the private sector, which denotes a policy ofprivatization far more audacious than those effected from the University Reform of 1968 made to meet the developmental aspirations of the country in the first decade of governments in the Military Dictatorship (1964-1985). During this period it was regulated the participation of the private sector in the provision of higher education, resulting in a rapid expansion of the sector. Thus, private institutions grew significantly, surpassing enrollment in public higher education institutions at the end ofthe military period, from 38.4% in 1964 to 59.1% in 1984 (Sousa, 2006; Martins, 2009). In this conjuncture, the education gained ground in the enterprise branch, becoming a profitable business, attracting entrepreneurs, many of them were not committed to education, but to profit.

For Martins (2009), it was in the government of President Fernando Henrique Cardoso (1995-2002) that the process of expansion of the sector exploded. In this period, only in the private sector, enrollments jumped from 1.7 million to 3.5 million, and in the last year of the President F. H Cardoso government, it was found one of the biggest growth peaks in higher education with the opening of 234 new private institutions, while the number of public universities in the same period, practically stagnated, according to the legal and juridical implemented by neoliberal prescriptions.

In Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva's government (2003-2010), the expansion process was even more intensified, however, accompanied by a strong movement of interiorization ofthe sector. With that, he resumed the growth of the public sector, with part of the funding shifted to the private sector to pay for scholarships and waiver of debts of the education companies. In the public sector, the strengthening occurred with the policy of higher education, technological and professional expansion. Thus, it was created the Program to Support Expansion Plans and Restructuring of Federal Universities, better known as Reuni, and the National Program of Access to Technical Education and Employment (Pronatec). Before Reuni, there were 148 campuses in federal institutions located in 114 municipalities, preferably in capital cities and major urban centers. From 2003 to 2010, 14 new universities were created, extending the picture to 274 campuses distributed in 237 municipalities, and by 2014 it is expected to reach a total of 321 campuses in 275 municipalities. In relation to technological and vocational training, in 2010 we reached the total of 354 campuses in Federal Institutes installed in 521 municipalities.

In the private sector, apart from the significant increase of new institutions nationwide, it has expanded the Student Financing Program for undergraduate courses through the FIES, including postgraduate studies. Furthermore, it was established the University for All Program (Prouni) which deals with the granting of full scholarships and partial in private HEIs, while it began to invest in centers of higher education on distance learning (ODL). Another important factor was the acquisition and merger of isolated HEIs, or even university networks already consolidated in the country by foreign groups and therefore constitutes the internationalization of private sector of higher education in Brazil (Sguissard, 2008; Martins, 2009).

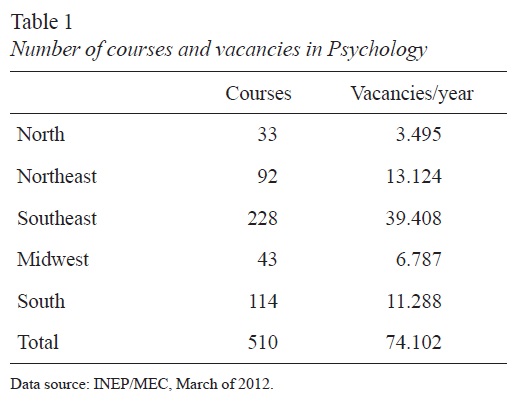

Regarding Psychology courses, we have 510 courses/qualifications, being 82 in public HEIs (11.7%) and 428 in the private sector (88.3%). In the table below you can see the number of vacancies offered annually, as well as the distribution of vacancies by region of the country.

The data presented corroborate the previously mentioned national indicators, and converge with the data reported in studies of Lisboa and Barbosa (2009) and Yamamoto, Silva and Zanelli (2010), especially in terms of the hegemony of the number of establishments and vacancies in private sector and the concentration of the number of course / vacancies in the South / Southeast, despite the growth of courses in other regions, particularly in northeastern Brazil. In 2011, it was enrolled nearly 160 thousand applicants for admission. Currently, Psychology is the tenth course in the national ranking in number of students, considering that it maintains 136420 students enrolled.

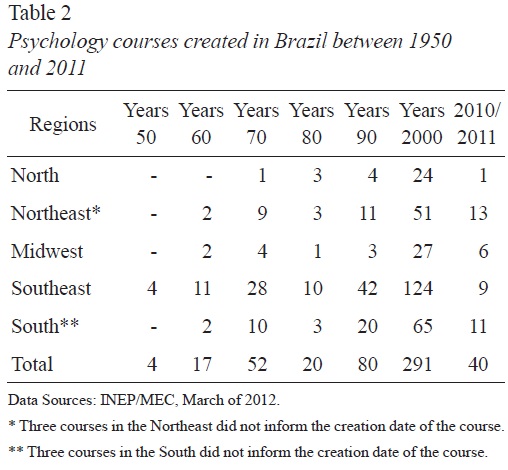

In Table 2 it can be seen that the first courses arrived even in the 1950s, and in the 60s and 70s a real explosion occurred of opening new courses, especially in the private sector, due to the Reform of 1968. Only this time of the years 60/70, 70 new courses were opened, 70% in private sector (Gomide, 1988). Note also that in the 1980s there was a slowdown in the expansion process due to the national economic crisis, expressed in a severe inflation and increasing unemployment rates in the country. In the mid-1990s, the sector returned to grow due to government stimulus for opening of private institutions and over 80 new courses. In the 2000s, the rise of privatization of the sector was intensified with the creation of 291 new courses, and only in 2011-2012, over 40 courses were opened.

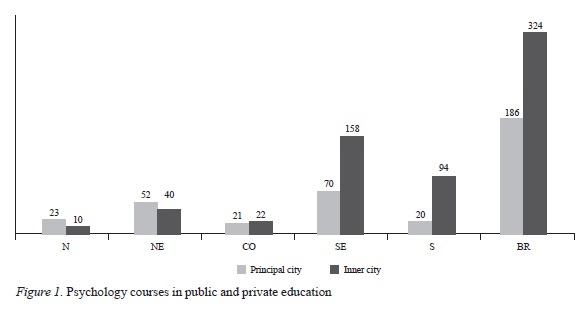

However, the high demand for entry into higher education in the late 1990s, especially in the development of regional centers of South and Southeast regions, and sub-development in the Northeast and Midwest, has made some private HEIs to preferr settling in the inner cities of Brazil as indicated in Figure 1. The objective was to search for new fields in the educational market (Neves, Raizer & Fachinetto, 2007).

It is observed that 63.5% of the courses are located in inner cities, while 36.5% are in the capital. On the first, at least 77 operate in midsize municipalities (100 to 300 000 inhabitants), 43 counties in medium-small (50 to 100 thousand inhabitants) and 27 in small towns (less than 50,000 inhabitants). The profile of the municipalities that have received Psychology courses is of cities that have determined economic and productive vocation, becoming the target of investment and urban planning. The main objective of these investments is the work of redefining the image of the city, so that they have consisted of local and regional development centers, capable of captaining resources, infrastructure investment, creating jobs, attracting tourists and generating new business (Sanches, 1999). Nevertheless, there are those cities with fragile urban infrastructure and services that rely merely on services connected to public policies and programs of technical assistance and rural extension. Generally, they are locations where there is a direct relationship with the rural areas, where the population of the countryside goes in search of those services (Leite, Macedo, Dimenstein & Dantas, 2013). Thus, there is the need to have a curriculum that responds to these new realities of academic and professional training of psychologists.

In the next session, we will present information on the internationalization of higher education and the effects that this process imposes on the training of psychologists in Brazil.

The formation of psychologists in times of internationalization of higher education

The internationalization of higher education gained momentum in Brazil with the neoliberal reforms which occurred in the 1990s. Among the major defining aspects of this policy in the country, it is cited: trade liberalization, financial liberalization, privatization of state companies, rising interest rates and a balanced budget through cutting social spending. Thus, the Brazilian state receded in its constitutional role to be directly responsible for the promotion of social services (health, education, security, etc.), which started to lose its character of rights, being offered by the private sector as a commodity.

Within the neoliberal prescription applied in Brazil, higher education was (and remains) a protagonist. International financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank started to pressure the Brazilian government and demanded changes in higher education, so that it would be considered a private good rather than public. The appearance of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995 was central to understanding the advance ofthe commodification and internationalization of education process in our country. Since its creation, the WTO was set up by a legal pillar (General Agreement on Trade in Services / GATS), which has education as one of the 12 major service sectors in the world. In order to fulfill the premises of the deal, it began to have an understanding of cross-border education: distance learning or presential modalities; movement of students to study abroad; formation of a horizon in which large commercial educational institutions could work in another country through local headquarters, satellite campus, twin institutions or franchise agreements with local institutions; beyond the displacement of teachers and researchers from one country to another to transfer knowledge and technology (Ribeiro, 2006).

Therefore, it was necessary to eliminate international barriers, changing laws of countries in order to promote access to international education market. The restrictions were on the electronic transmission of materials, non-recognition or accreditation of the foreign institution, as well as the recognition of diplomas, charging excessive taxes or fees for license or royalty payments, government monopolies in the educational sector and high level of subsidy to the national provider, among other barriers (Ribeiro, 2006).

In the national context, it is clear the presence of many of these guidelines of multilateral institutions on legislation that deals with higher education. The very LDB of 1996 and supplementary legislation (Decree 2306 of 1997) came forward with deregulation measures of education, placing it as a marketable service, subjected to the system of mercantile law (Sguissardi, 2008). The conjuncture of multilateral agencies influence, allied to Brazilian economic stability, the potential growth of private educational sector, with its large and voracious expansion process, captained by legislation that supports the transformation of the sector, and all this combined with a huge demand (hitherto repressed) for entry into higher education, consolidates Brazil as a bustling educational market, open to private sector and capital, whether domestic or foreign.

With a legal apparatus and a heated educational market, Brazil enters the sight of major international networks. Thus, the first foreign groups to enter the Brazilian educational market were the American groups Apollo International, Laureate International Universities, Whitney International University System and Devry University. The scenario of the internationalization of higher education in Brazil started to be formed in 2001 when the group Apolo International, outer arm of the holding University of Phoenix, acquired 50% of the group Pitágoras to open its University in the State of Minas Gerais. Currently, the group is no longer in Brazil. Another large group that showed interest in the educational market in Brazil was the Laureate International Universities. Founded in 1998, in the United States, the group is today one of the largest global networks of higher education, present in all continents, specifically in 29 countries, totaling 69 institutions and more than 700 thousand students. In Brazil, the group is in eight states of the federation, with eleven HEIs and over 40 campuses.

Laureate Group began to examine the Brazilian market in 2001, and its first acquisition occurred in December 2005, with the purchase of 51% of University Anhembi Morumbi (São Paulo), which has a Psychology course. Subsequently, the group acquired more Brazilian HEIs amongst which we highlight those that have Psychology courses: University Potiguar on the State of Rio Grande do Norte (2), Faculty Guararapes in Pernambuco (1), School of Law and Economics Administration (ESADE) in Rio Grande do Sul (1), University Center North (UNINORTE) in Amazonas (1), Brazilian Institute of Rehabilitation Medicine (IBMR) in the State of Rio de Janeiro (1), Salvador University (UNIFACS) in the State of Bahia (2), United Faculty of Paraíba (UNPB) and the Centro Universitario Ritter dos Reis (UniRitter) in Rio Grande do Sul. In addition, 17 HEIs offer Psychology courses in Latin America and Europe, totaling 24 institutions: Brazil (9), Chile (3), Costa Rica (2), Honduras (2), Mexico (3), Panama (1), Peru (2), Cyprus (1), UK (2) and Turkey (1).

In 2006 the Whitney International University System arrived in Brazil. It is a chain located in Texas (USA), which focuses on Latin American students, offering courses in the United States, Argentina, Colombia, Panama, Chile, North Africa and the Middle East, among others. In Brazil, the Group Whitney acquired 50% of the Faculty Jorge Amado (UNIJORGE) in the State of Bahia. The other acquisition of the group was in 2011 with the purchase of University Veiga de Almeida, situated in Rio de Janeiro. Both have Psychology courses. The third international group to settle in Brazil, more specifically in the Northeast, was the Devry University. This is a network of open capital with more than 90 campuses present in 30 countries. The first acquisition of Devry occurred in 2009 with the group FANOR in Ceará, now known as Devry Brasil. Besides this, four other institutions were acquired, two located in the State of Bahia - Faculty of Área-1 and Faculty Ruy Barbosa; the other located in Pernambuco - Faculty Boa Viagem; and more recently Faculty FACID, in the State of Piauí, was acquired. Among them, FANOR, Faculty Ruy Barbosa and Faculty FACID have Psychology courses.

In summary, the three groups have acquired 18 institutions of higher education, present in nine states ofthe federation: Amazônia (Northern Region), Ceará, Piauí, Rio Grande do Norte, Pernambuco and Bahia (Northeast), São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro (Southeast Region) and Rio Grande do Sul (Southern Region). Regarding Psychology courses related to these groups, it counts up the total of 14, spread in the Northeast (9), South (1), Southeast (3) and North (1). Once again the Brazilian Northeast appears as the most attractive region for investment in higher education, and the interest is also related to the internationalization of leading universities operating in the region.

The internationalization of higher education has opened a new debate about the risk of interferences in Brazilian education. The warning is about the loss of autonomy and educational denationalization and decontextualization of teaching, bringing it to foreign standards, so distant from the Brazilian reality. Despite constant statements of the foreign groups of non-interfering in Brazilian education, because what matters to them is business, ie, monitor financial ratios and economic institutions such as the purchase of well-structured, solid and profitable new investments (Castro, 2008), there is some alignment on the hour load, profile of graduates and some curriculum components, for example, subjects, menus and sometimes the actual curricular matrix of some courses internationalized - Psychology is an example of this. The argument is to ensure the double degree (domestic and foreign) to students who attend part of the graduation at another institution of the network while also allowing academic exchanges and partnerships for joint activities.

One of the risks of this alignment as for the profile of graduates and internationalized course curriculum is to make them more homogeneous, with little standardization of content and diversification of local educational experiences. Agreeing with Lima and Maranhão (2011), it is undeniable that the internationalization of higher education in Brazil may show many positive points, especially if we look through the prism of students who will expand their academic scope and professional networks with cooperation of research and transfer of technologies, exchange of practical and professional experiences and learning from other cultures. On the other hand, the authors remind that the process of internationalization under the argument of valuation of multiculturalism, multilingualism and double degree, often tends to promote the curriculum, cultures and consciences standardization to adopt the education model advocated by the hegemonic countries. That is, ultimately transforming higher education in cultural tool industry for, "instead of promoting diversity, the standardization of services offered prevails - the architecture of the courses, the design of curricula, the formulation of the curriculum (...), explored methodologies, evaluation system, required internships models and sometimes, the language adopted" (Lima & Maranhão, 2011, p. 593. Our emphasis).

In this sense, we need to look carefully at the process of internationalization of education in Psychology occurring in the country (and higher education in general), not running the risk of distance ourselves from the idea of National Curriculum Guidelines (DCN) for the Psychology course, which is promoting a training based on the full and contextualized understanding of psychological phenomena and processes, enhancing practical possibilities and the production of knowledge in different social and institutional contexts. Such principle has marked, excessively, Brazilian Psychology, since when it started to get involved in public policies and social and cultural diversity of our country.

Closing Reflections

The expansion of higher education set new scenarios for the training of psychologists in Brazil. On one hand, progress was made with the implementation of courses in interior counties (63.5%) surpassing the number of courses located in capital cities (36.5%). On the other, with the process advancement of the higher education commodification in our country, three international educational groups acquired 18 institutions of higher learning, including fourteen feature Psychology courses.

The internalization training of psychologists, intensified in the last decade, is, from our perspective, a phenomenon that repositions our profession not only characterized as urban and connected to capitals or big cities, as traditionally it was known until the end 1990s. Psychology courses are more and more present in the municipalities of medium and small. Thus, we consider important the approximation of educational institutions with the reality of smaller municipalities, including the countryside, so as to cause reflections in the curricula in order to create spaces for dialogues between psychology education and various social issues, discussing relevant matters to the population of these municipalities.

Generally, the counties with smaller population sizes impose a new reality for our profession because they are mostly places that have a high rate of rural population (44.93%), whose main productive activity is family farms, also highlighting the family farming and fishing, or vegetable and mineral extraction, b) economic and administrative weakness, resulting in dependency on actions and programs by the federal government, c) insufficient responses to the needs of the population, due to centralized, authoritarian and clientelistic management practices, and d) a population reality that concentrates basic social problems, such as infant mortality, illiteracy, child labor and malnutrition, hunger, poverty, difficulties of transport, especially the displacement from rural a the cities and unemployment; and they even face typical problems of large urban centers, such as increased crime and violence, increased rates of chronic degenerative diseases, teenage pregnancy, traffic deaths (motorcyclists), prostitution, trafficking and consumption of drugs (Macedo & Dimenstein, 2011).

As for the rural areas, the social problems mentioned above are aggravated due to lack of basic infrastructure, deterioration of public policies, need to strengthen the rural settlements projects and investment in family farming, lack of opportunities for education, work and health field, besides the problems and conflicts related to agribusiness, productive accumulation and the technification of work in the field, violence and other transformation of rural reality.

From this perspective, do we wonder how our psychological theories and practices have concerned (or even engaged in their activities) about rural contexts? Do we start from the understanding of rural as a bucolic and idealized space, as delays and life ways to be overcome by progress, or as a conflictive space, marked by dynamic and varied processes, diverse, permeated by situations of exploitation and expropriation of rights? Have we considered the new spatial dynamics and the emergence of new ways of sociability through the transformation of life ways that is seen in smaller cities, or have our formations simply repeated our historic feat of selecting and adapting people in order to improve their standard of responses through the demands of modern civilized life? For sure it is not the object of this study to answer the above questions, but worry them to the concern that the approach of the courses with the reality of smaller cities requires major transformations in the formation of Brazilian psychologists facing an unknown reality for many professionals our area.

About the expansion of transnational market in the university sector and the requirements for applying its logic to Brazilian institutions with strategies for internationalization and globalization of education, this has led to advances in strengthening the mobility of students and teachers, establishing mechanisms for cooperation and institutional networks of researchers, establishing mutual recognition agreements in the validation of diplomas, besides opening branches of educational institutions internationally consolidated, creating transnational networks of virtual universities and higher education transnational (Van Damme, 2001).

However, according to Morosini (2006), the application of the transnational market requirements to Brazilian institutions also presents new challenges for higher education in the country: a) the maintenance of education as a public service , despite pressures to become a commercial service; and b) the risk of internationalization of curricula, without considering these effects on the processes of teaching and learning, on the construction of identity and on the social adjustment of the student facing new demands and requirements of the local and global market. This debate is important because in Brazil there is a diversity of stakeholders interested in promoting the positive aspects and virtues of internationalization. However, it is necessary to consider that the internationalization goes beyond issues related to cooperation and academic mobility, since it has evolved for the provision of services abroad, involving mobility of experts in strategic areas of interest, cross-border graduation and professional development programs organized in a way that students can be in the class or far from it that distinguished themselves worldwide, and the opening of academic units (Campi and Universities) abroad, exacerbating the sector market.

The commodification of higher education has brought consequences that need to be further discussed by the Brazilian society, especially due to the danger of reducing education to a market issue and the many interferences regarding the functioning of educational institutions: replacement of the academic and scientific cooperation principle by competition; import of theories instead of valuing local knowledge and loco-regional needs of the population; replacement of intellectual and critically engaged training by the technical logic adaptive solutions of experience transferred from one reality to another uncritically.

These issues directly affect the organization of the curriculum and the processes of training and management of the internationalized higher education courses in Brazil. Nevertheless, what are the parameters and principles that have supported the debate on the alignment of curriculum between courses that make up the chain of international groups? And the research and the partnerships of cooperation, development and technology transfer, how have they been happening? Undoubtedly, there are important issues to think about the effects of globalization and internationalization on higher education in the country process. Therefore, the need to deepen the theme and carry future studies which can monitor the effects of this process on the formation of the Brazilian psychologist, especially because the contexts in which we are today are the public policies, that besides the generalist mark for our training, it is a reality that requires linked action to with areas of knowledge, work in multidisciplinary teams and an ongoing dialogue with local knowledge from interventional and participatory methodologies. These issues can get lost in a possible homogenization of curricula with parameters that do not meet the specificities of regional and Brazilian reality.

In this sense, regardless the internalization or the internationalization prism of psychologists training, it is necessary that our professionals are best qualified to handle the subjective processes that underlie individuals, groups and other collectives from social dynamics and characteristics of the territory they inhabit. Thus, territory, social and subjectivity processes are important categories to guide the training of future professionals, including being aware not to make the mistake oftransferring the understanding of psychological and psychosocial processes consisting in urban spaces to the context of rural areas.

Another precaution to be taken is the danger of naturalizing the notion of rural, characterizing it as spaces restricted to agricultural activity, since the geographical and cultural isolation, with restricted mobility capability. The Brazilian countryside has undergone an intense "process of restructuring their social systems through the incorporation of new economic, cultural and social elements" (Carneiro, 2005 p.10). In this case, psychology courses in general, including internationalized ones, need to consider in their curricula the spatial, social and symbolic heterogeneity, sometimes conflicting and ambiguous, that pervades Brazilian reality.

References

Bastos, A. V B., Gondim, S. M. G. & Rodrigues, A. C. A. (2010). Uma categoria profissional em expansão: quantos somos e onde estamos? In A. V. B. Bastos & S. M. G. Gondim (Orgs.), O trabalho do psicólogo no Brasil (pp. 32-44). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Bock, A. M. B. (1999). Psicologia a caminho do novo século: identidade e compromisso social. Estudos de Psicologia, 4(2), 315-329. [ Links ]

Brasil. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira (2011). Censo da Educação Superior - 2010. Brasília, DF: Ministério da Educação. Recovered in http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=17212 [ Links ]

Carneiro, M. J. (2005). Apresentação. In R. J. Moreira (Org). Identidades sociais: ruralidades no Brasil contemporâneo (pp. 7-14). Rio de Janeiro: DP & A. [ Links ]

Castro, C. M. (2008, Abril 1). Internacionalização do Ensino Superior: invasão de farmacêuticas ou de marcianos? Interesse Nacional. Recovered in http://interessenacional.uol.com.br/2008/04/internacionalizacao-do-ensino-superior-invasao-de-farmaceuticas-ou-de-marcianos [ Links ]

Conselho Federal de Psicologia. (1988). Quem é o Psicólogo brasileiro? São Paulo: Edicon. [ Links ]

Conselho Federal de Psicologia. (1994). Psicólogo brasileiro: práticas emergentes e desafios para a formação. São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo. [ Links ]

Conselho Nacional de Educação. (2004). Notícia: diretrizes curriculares nacionais para os cursos de graduação em psicologia. Psicologia: teoria e pesquisa, 20(2), 205-208. [ Links ]

Ferreira Neto, J. L. (2011). Psicologia, políticas públicas e o SUS. São Paulo: Escuta; Belo Horizonte: FAPEMIG. [ Links ]

Gomide, P. I. C. (1988). A formação acadêmica: onde residem suas deficiências. In Conselho Federal de Psicologia. (Org.), Quem é o psicólogo brasileiro? (pp.69-85). São Paulo: Edicon. [ Links ]

Leite, J. F., Macedo, J. P., Dimenstein, M. & Dantas, C. (2013). A formação em Psicologia para a atuação. In J. F. Leite & M. Dimenstein. Psicologia e contextos rurais (pp. 27-56). Natal, Rn: EdUFRN. [ Links ]

Lima, M. C. & Maranhão, C. M. S. A. (2011). Políticas curriculares da internacionalização do ensino superior: multiculturalismo ou semiformação? Ensaio: avaliação de políticas públicas em educação, 19(72), 575-598. [ Links ]

Lisboa, F. S. & Barbosa, A. J. G. Formação em psicologia no Brasil: um perfil dos cursos de graduação. Psicologia: ciência eprofissão, 29(4), 718-737. [ Links ]

Macedo, J. P. & Dimenstein, M. (2011). Expansão e interiorização da Psicologia: reorganização do saberes e poderes na atualidade. Psicologia: ciência eprofissão, 31(2), 296-213. [ Links ]

Martins, C. B. C. (2009). A reforma universitária de 1968 e a abertura para o ensino superior privado do Brasil. Educação e Sociedade, 30(106), 15-35. [ Links ]

Morosini, M. C. (2006). Estado do conhecimento sobre internacionalização da educação superior: conceitos e práticas. Educar em revista, 28(1), 107-124. [ Links ]

Neves, C. E. B., Raizer, L. & Fachinetto, R. F. (2007). Acesso, expansão e equidade na educação superior: novos desafios para a política educacional brasileira. Sociologias, 9(17), 124-157. [ Links ]

Ribeiro, G. F. (2006). Afinal, o que a Organização Mundial do Comércio tem a ver com a educação superior? Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional, 49(2), 137-156. [ Links ]

Rocha, Jr., A. (1999). As discussões em torno da formação em psicologia às diretrizes curriculares. Psicologia: teoria e prática, 1(2), 3-8. [ Links ]

Sánchez, F. (1999). Políticas urbanas em renovação: uma leitura crítica dos modelos emergentes. Rev. Bras. Estudos Urbanos Regionais, 1(1), 115-132. [ Links ]

Sguissardi, V (2008). Modelo de expansão da educação superior no Brasil: predomínio privado/mercantil e desafios para a regulação e a formação universitária. Educação e sociedade, 29(105), 991-1022. [ Links ]

Sousa, J. V. (2006). Restrição do público e estímulo à iniciativa privada: tendência histórica no ensino superior brasileiro. In M. A. Silva, & R. B. Silva (Orgs.). A ideia de universidade (pp. 139-178). Brasília, DF: Líber Livro. [ Links ]

Van Damme, D. (2001). Quality issues in the internationalization of higher education. Higher Education, 41, 415-41. [ Links ]

Yamamoto, O. H., Silva, J. A. J. S. N. & Zanelli, J. C. (2010). A formação básica, pós-graduada e complementar do psicólogo no Brasil. In A. V. B. Bastos, & S. M. G. Gondim (Orgs.), O trabalho do psicólogo no Brasil (pp. 45-65). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

To cite this article: Macedo, J. P., Dimenstein, M, De Sousa, P. A., Magellan, D., Alves, M., De Sousa, S. F. (2014). New scenarios of training in psychology in Brazil. Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana, 32 (2), 321-332. doi: dx.doi.org/10.12804/apl32.2.2014.10