Self-Regulated Learning (SRL) encompasses motivational and metacognitive components often associated with reading comprehension proficiency (Frijters et al., 2018; Mahmoodi & Karampour, 2019; Shell et al., 1995; Yau, 2021). In SRL, intrapersonal causal attributions allude to the metacognitive ability of self-reflection on academic performance. The way students attribute causality to success and failure outcomes can prospectively impact student motivation (Graham, 2020; Weiner, 2010).

After evaluating themselves as successful or unsuccessful, students attribute causes to their success or failure. Weiner (2010) explained this is due to four causes: ability -also conceived as intelligence and aptitude, effort, level of task difficulty, and luck. Intrapersonal causality attributions also involve three psychological dimensions: the degree to which one recognizes locus -internal or external, stability- stable or unstable, and controllability -controllable or uncontrollable- (Graham, 2020; Weiner, 2010).

How causality is attributed to situations of success and failure is characterized as functional when, in most cases, students understand academic performance as a product of their effort and ability. It is essential to highlight that effort is unstable and controllable, and ability is commonly assessed as stable and less controllable. These causes are associated with a higher level of responsibility for learning processes due to the internal locus (Almeida & Guisande, 2010; Graham, 2020; Weiner, 2010). Dysfunctional causal attribution is expressed in the recurrent manifestation of task difficulty and luck to justify success and failure situations at school. Both causes have external loci and are uncontrollable; they differ only in terms of stability -task difficulty is seen as more stable, while luck is perceived as more unstable- (Graham, 2020; Weiner, 2010).

How students qualify the causes attributed to psychological dimensions -functional and dysfunctional- can generate a pattern of adaptive and maladaptive beliefs about the learning process. Adaptive causal attributions foster students' motivation, while maladaptive beliefs affect their demotivation (Almeida & Guisande, 2010; Graham, 2020). Therefore, investigating them helps formulate intervention programs, called attributional retraining, aimed at working on students' motivation to learn through pedagogical practices consistent with their pattern of causal attributions. However, for the foundation of interventional techniques, it is necessary to properly evaluate causality's attributions through measuring scales with acceptable psychometric properties.

In that regard, this study focused on causal attributions for success and failure in reading comprehension in middle school. Generally, reading comprehension is characterized as a mental construction of the material read (Kintsch & Rawson, 2013). In middle school, the reading ability underlies the application of procedures consistent with the purposes of reading and the specificities of the textual material, the articulation of prior knowledge with the content read, the transition through different textual genres, and the establishment of intertextuality (Brasil, 2017).

The Frijters et al. (2018) study with American students of Hispanic and African descent revealed the magnitude of the correlations between intra-personal causal attributions and reading. The prediction values of this construct for this linguistic ability vary according to the reading skill level. In addition to reading or reading comprehension performance, attributing causes linked to the psychological dimensions of internal and controllable loci (e.g., effort) seems to support students' motivation. It indicates that more significant efforts in other activities requiring reading increase the chances of achieving success (Mahmoodi & Karampour, 2019). Accordingly, Yau (2021) considered that causal attributions within the SRL process are associated with motivation, emphasizing students' self-efficacy beliefs to use strategies that promote good performance in reading comprehension. The meanings of Yau (2021) regarding self-efficacy are congruent with the statements of Schunk (1994), who, in addition, emphasized the role of causal attributions in SRL in comparing and analyzing one's performance, not only to the result achieved but also regarding its association with the pre-established objectives (goals).

Achievement goals refer to the interaction of personal beliefs with the learning context (e.g., school climate, teacher feedback) that result in motivational predispositions related to how students set their goals (Bardach et al., 2020; Urdan & Kaplan, 2020). A more internal motivational focus prevails over the learning goal, characterized by interest, persistence, and positive emotions regarding the intellectual gains acquired with the learning process. Performance-approach and performance-avoidance goals prioritize the results. Concerning the performance-approach goal, students' motivation is to demonstrate high skills. In the performance-avoidance goal, the intention is to preserve themselves from situations that show a lack of ability (Urdan & Kaplan, 2020). Self-efficacy beliefs, in turn, represent students' self-perceived competencies regarding specific domains present in the learning process, such as reading comprehension (Bandura, 2005; Shell et al., 1995; Vezzani et al., 2018).

The motivational constructs in SRL present mutual relationships. In the study by Wolters et al. (2013), self-efficacy and achievement goals were predictors of causal attributions. In Ferraz et al. (2020), causal attributions for successful situations were predictors of the learning goal and performance-avoidance goals. In turn, attributing causes for failure predicted achievement goals and the performance-avoidance goal.

Regarding self-efficacy, Shell et al. (1995) found that the different levels of reading performance were related to self-efficacy for the performance of tasks involving this linguistic skill. In turn, the attribution of causes such as ability and luck were identified only in the groups with medium and low performance in reading. The study by Vezzani et al. (2018) analyzed the structure of an explanatory model for Italian students' conceptions of their general learning process. In successful situations, the attributions of internal locus were related to self-efficacy, openness to challenges, and personal growth perception. The same was not verified for general cases of failure.

This study aimed to investigate the initial psychometric properties of the Causal Attributions Scale for Reading Comprehension -Escala de Atribuições Causais para a Compreensão de Leitura (EAC-CL)- (Ferraz & Santos, 2019). This investigation was based on the analysis of the evidence of content validity, validity based on internal structure, and validity based on the relationship with other variables: achievement goals and self-efficacy (American Educational Research Association [AERA], American Psychological Association [APA], & National Council on Measurement in Education [NCME], 2014). The selection of constructs for studying the psychometric quality of the EAC-CL is due to self-efficacy and achievement goals being motivational constructs linked to the SRL process (Ferraz et al., 2020; Frijters et al., 2018; Wolters et al., 2013) and intrapersonal causality attributions (Mahmoodi, & Karampour, 2019; Yau, 2021). Additionally, we hypothesized the existence of relationships between these constructs based on previous studies (Ferraz et al., 2020; Frijters et al., 2018; Vezzani et al., 2018; Wolters et al., 2013). It is essential to point out that Brazil still has no instrument to assess the attributions of causality directed toward reading comprehension. Therefore, the present research aims to fill this gap, whose relevance is perceived both for the scientific field and the professional practice of psychologists and educators.

General Ethical Considerations

This paper comes from a project approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Universidade São Francisco (Authorization No. 3.263.350). Professors/researchers who acted as expert judges signed the consent form to participate in the study. Upon acceptance by the schools, the stages of the research that involved the students required the presentation of the consent form signed by one of the parents/guardians, with the students signing another consent form.

Construction of the Causal Attributions Scale for Reading Comprehension

The construction of the EAC-CL was based on previous research on intrapersonal causality attributions (e.g., Ferraz et al., 2020; Graham, 2020; Weiner, 2010; Zimmerman & Risemberg, 1997). Ferraz and Santos (2019) elaborated on two hypothetical situations to assess the students' causal attributions for cases involving excellent and poor performance in reading comprehension. They were named Situation A and Situation B. Four items were created for each situation. Therefore, the EAC-CL has eight items. The first item assesses what causes students to attribute doing well or poorly in reading comprehension. The answer options are ability, effort, text difficulty, or luck. The second item assesses the locus of control, in which students are asked to determine whether the cause attributed in item 1 of both situations is an internal or external locus. The third item measures stability, asking them to evaluate whether the previously assigned reason is stable or unstable. The fourth item investigates controllability: students must indicate whether the attributed cause is controllable or uncontrollable.

It should be highlighted that the EAC-CL is part of the Multidimensional Battery of Self-Regulation for Reading Comprehension (Bateria Multidimensional da Autorregulação para a Compreensão de Leitura [BAMA-Leitura]). In addition to motivation, the battery assesses reading strategies, time management, self-monitoring, self-reactions, self-selection of the physical environment, and seeking selective help (Ferraz & Santos, 2019). The BAMA-Leitura scales that assess motivation were used in this research: Self-Efficacy Scale for Reading Comprehension and the Achievement Goals Scale for Reading Comprehension.

Method

Stage 1. Investigation of Evidence of Content Validity of the EAC-CL

Sub-Stage 1. 1. Expert Judges' Analysis

Participants. Three higher education professors with a mean experience of 16.66 years (SD = 13.87) in developing research on the topic addressed in the EAC-CL. The judges had PhDs in Psychology.

Instrument. Judges'Evaluation Protocol (Ferraz & Santos, 2019). The protocol was based on the Content Validity Coefficient (CVC) procedure (Hernández-Nieto, 2002). The evaluation of the items of the EAC-CL focused on language clarity (LC), practical relevance (PR), theoretical relevance (TR), and the theoretical dimension (TD).

Data collection procedure. The judges were selected from the contact network of the researchers responsible for the study. The Judges' Evaluation Protocol was answered remotely using the Google Forms platform.

Data analysis procedure. The CVC of the constant in the LC, PR, and TR criteria was calculated for each item of the EAC-CL and the total CVC for situations A and B. The theoretical dimension was calculated through Fleiss' Kappa (k), in which the agreement between judges can range from -1 to 1. The reformulation and exclusion of items were based on CVC < .80 and k < .39 (Hernández-Nieto, 2002). Item restructuring also considered the qualitative analysis of the judges' comments (AERA et al., 2014).

Results Substage 1. 1.

In Situation A, "Most of the time, I am good at reading comprehension. This is because..." The CVCC values for LC, PR, and TR validation criteria corresponding to the four items were between .89 and .96, and k = 1. The LC validation criterion obtained cvct = .91 and the PR and TR validation criteria = .89. The Four Items in Situation B "Most of the time I do poorly in reading comprehension. This is because..." obtained CVCC = .96 in the three validation criteria, and CVCT = .92. In both situations, the EAC-CL obtained k = 1 (100 % agreement). Based on the judges' observations, changes were made to the wording of the items. In item 4 of situations A and B, the word 'speak' was replaced by 'say.' In item 1 of Situation B, the response option that refers to the lucky cause was changed from "I am an unlucky person" to "I am not a lucky person."

Sub-Stage 1. 2. Interview with the EAC-CL Target Audience

Participants. Participants were 16 middle school students (municipal school in São Paulo state), four from each school year, with equal distribution between the sexes. The minimum age was 11 years, and the maximum was 15 (M age = 13 years; SD = 1.31).

Instrument. Target Audience Assessment Protocol (Ferraz & Santos, 2019). The Protocol contains an interview to assess the comprehension of the EAC-CL target audience. Part I of the Protocol estimated the intelligibility of the EAC-CL statement and response keys (six items). Part II of the Protocol measured the intelligibility and representativeness of the EAC-CL items in the school routine of the Middle School students (four items).

Data collection procedure. The interviews were carried out individually, in person, and during class. The students took, on average, 15 minutes to complete the Target Audience Assessment Protocol.

Data analysis procedure. The student responses to the Target Audience Assessment Protocol were calculated using frequency values (Microsoft Excel®). The comments were analyzed qualitatively, prioritizing the comprehension and relevance of the EAC-CL to the reality experienced by the students (AERA et al., 2014). The results of the quantitative and qualitative analyses guided the reformulation and exclusion of items.

Stage 1. Results

Regarding the statement, in item 1 of Part I of the Target Audience Assessment Protocol, 87.5 % of the students (n = 14) indicated that they understood the instructions for completing the EAC-CL. In item 2, 68.8 % of the students (n = 11) reported not identifying any confusing parts in the statement. In item 3, none of the students reported unknown words. Through the observations of the students who indicated that they did not understand the instructions of the scale, as well as those who rated some parts as confusing, it was found that the difficulty did not refer to the content of the EAC-CL statement but to the need to show them the instrument in its entirety. After overcoming this difficulty, the observations of the students guided the rewriting of the statement: "We want to know what causes, for you, explain having done well or poorly in reading comprehension. Consider situations A and B presented below and mark an X on best explanation. You must be honest in your answers. Just mark an X in each alternative" - the italicized passages were changed to 'on the item' and 'sincere.'

The evaluation of Part II of the Target Audience Assessment Protocol showed no similar content in the four items of situations A and B of the EAC-CL. In situation A, one student (6.3 %) demonstrated difficulty understanding the association between the items and response options. This condition was solved by providing further explanations about the functioning of the scale. In situation B, the students could comprehend the items and their answer alternatives easily. The only change made to items 2, 3, and 4 of cases A and B of the EAC-L was the change of punctuation to transform them into a statement, changing the punctuation: question mark for the period.

Stages 2 and 3. Investigation of Validity Evidence Based on the Internal Structure of the EAC-CL and Its Relationship with Other Variables

Participants. The sample was composed of 522 middle school students from three public schools located in São Paulo state, with n = 132 (25.3 %) from the 6th year, n = 159 (30.5 %) from the 7th year, n = 128 (24.5 %) from the 8th year, and n = 103 (19.7 %) from the 9th year. Age ranged from 10 to 18 years (Mage = 12.72; SD = 1.26). Of this sample, 280 were female (53.6 %), and 90 students had failed school at least once (17.3 %).

Instruments. Causal Attributions Scale for Reading Comprehension -EAC-CL- (Ferraz & Santos, 2019). The EAC-CL assesses the intrapersonal causal attributions for reading comprehension of middle school students. The scale has two situations, containing four items each. Situation A involves a hypothetical condition where students had successful reading comprehension, while situation B proposes failure in this cognitive-linguistic skill. Students are instructed to consider each situation and attribute a cause: ability, effort, task difficulty, or luck. Then, they were asked to classify the attributed cause in the psychological dimensions of the locus -internal or external, stability- stable or unstable, and controllability -controllable or uncontrollable-.

Achievement Goals Scale for Reading Comprehension (Escala Metas de Realização para a Compreensão de Leitura [EMR-CL] ; Ferraz & Santos, 2021). The EMR-CL assesses the achievement goals for reading comprehension of middle school students. It has 20 items divided between three factors: Learning Goal, Performance-Approach Goal, and Performance-Avoidance Goal. The answer key is a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from Not True to Totally True.

Self-Efficacy Scale for Reading Comprehension (Escala Autoeficáciapara Compreender a Leitura [EA-CL]; Ferraz & Santos, 2021). The EA-CL assesses the self-efficacy beliefs of Middle School students for activities that demand reading comprehension. The EA-CL is unifactorial and has 17 items. The response format is a Likert-type scale (4-points), ranging from Not Capable to Totally Capable.

The EMR-CL and EA-CL present validity evidence based on internal structure and content validity. These scales also have reasonable reliability estimates (Ferraz & Santos, 2021).

Data analysis procedure. Analysis of the internal structure of the EAC-CL. The theoretical classification of the causes (ability, effort, task difficulty, and luck) with the psychological dimensions (locus, stability, and controllability) was based on the propositions of Weiner (2010), Almeida and Guisande (2010), and Graham (2020). For ability: internal locus, stable and uncontrollable; effort: internal locus, unstable and controllable; task difficulty: external locus, stable and uncontrollable; luck: external locus, unstable and uncontrollable were considered functional. From this classification, four groups were formed: Group 1 Adaptive (G1A) - the three psychological dimensions linked to the causes attributed by the students in situations A and B matched the theoretical classification (functional); Group 2 Maladaptive 1 (G2D1) - presentation of one psychological dimension categorized as dysfunctional; Group 3 Maladaptive 2 (G3D2) - the presence of two dysfunctional psychological dimensions; and Group 4 Maladaptive 3 (G4D3) - three dysfunctional psychological dimensions.

The observed association between the causes and the psychological dimensions was analyzed through the Chi-Square test (X2) - using SPSS Statistics, version 25.0. The adjusted residual value (AR) >2 was the reference for verification of the comparison effect between the variables in which the result of the J2 test was statistically significant (p < .05). The effect size between the comparisons was evaluated using Cramer's V and Phi (Field, 2009).

The sample data's normality was verified to investigate evidence of validity based on the relationship with other variables for EAC-CL. The results of the Shapiro-Wilk test with p < 0.05 found that the data did not have a normal distribution for (1) the causes presented in situations A and B of the EAC-CL, (2) the classifications of the psychological dimensions linked to the causes -functional/dysfunctional (3) the four classifications of causes groups (adaptive/maladaptive), (4) the EMR-CL factors, and (5) the EA-CL.

Comparison of groups: The Kruskal-Wallis (H) and Mann-Whitney (U) tests, with Kolmogorov-Smirnov z (Z K-S ) (Field, 2009). The effect size of the statistically significant comparisons of both tests was verified considering r values < .49 (small), between .50 and .79 (medium), and > .80 (large) (Cohen, 1992).

Stage 2 and 3 Results

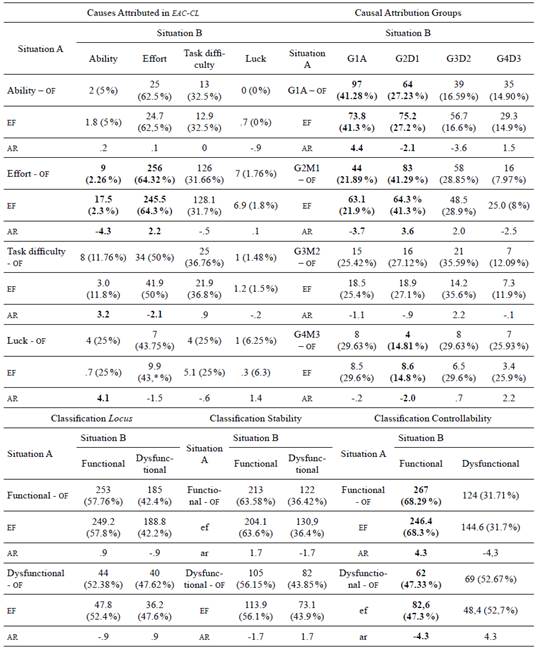

To analyze the internal structure of the EAC-CL, the associations existing between the causes and the psychological dimensions of the EAC-CL obtained from the sample of middle school students were investigated. In Situation A, referring to being successful in reading comprehension, the attributions to the effort, task difficulty, and luck presented statistically significant associations with the psychological dimensions' locus - x 2 (3) = 52.536 (p < .001), Cramer's V = .32, and controllability - X2 (3) = 57.881 (p < .001), Cramer's V = .33, and the attribution to ability with stability - X2 (3) = 16.610 (p = .001), Cramer's V = .18 (Table 1).

Table 1 Associations between Causes Presented in EAC-CL with Psychological Dimensions

Legend. OF = Observed Frequency; EF = Expected Frequency; AR = Adjusted Residuals.

Note. Values in bold indicate statistically significant comparisons based on adjusted residual values.

In situation B of the EAC-CL, in which the situation of failure in reading comprehension is considered, the attributions to effort and to task difficulty presented statistically significant associations with the psychological dimension of controllability X2 (3) = 20.974 (p < .001), Cramer's V = .20. No statistical significance was observed in the comparisons between the causes and the psychological dimensions locus - X2 (3) = 5.649 (p = .13), Cramer's V = .10, or stability - X2 (3) = 1.640 (p = .65), Cramer's V = .06 (Table 1).

Next, there was a statistically significant effect in the comparison of causes attributed in situations A and B of the EAC-CL - X2(9) = 34.091 (p < .001), Cramer's V = .15. As shown in the upper left of Table 2, the only cause that presented a statistically significant difference in both situations was the effort. Furthermore, statistically significant effects were obtained when comparing effort (Situation A) with the ability (Situation B), the difficulty of the task (Situation A) with ability and effort (Situation B), and luck (Situation A) with ability (Situation B).

Table 2 Associations between Situations A and B: Causes of EAC-CL, Causal Attribution Groups and Classification of Psychological Dimensions

Legend. GlA = Adaptative Group; G2M1 = Maladaptive Group - One Dysfunctional Cause; G3M2 = Maladaptive Group - Two Dysfunctional Causes; G4M3 = Maladaptive Group - Three Dysfunctional Causes; OF = Observed Frequency; EF = Expected Frequency; AR = Adjusted Residuals.

Note. Values in bold indicate statistically significant comparisons based on adjusted residual values.

Concerning the classification of the psychological dimensions into functional and dysfunctional, there was a statistically significant effect when comparing the controllability classifications in situations A and B -x2 (1) = 18.496 (p < .001), see bottom of Table 2). No statistical significance was found in the comparisons involving the classifications of the locus and stability psychological dimensions - x2 (1) = 0.832 (p = .36) and x2 (1) = 2.785 (p = .09), respectively.

Also, considering the results presented in the upper right part of Table 2, associations were found in the groups of causal attributions for situations A and B of the EAC-CL - x2 (9) = 43.077 (p < .001), Cramer's V = .17. Based on the adjusted residual values of the comparisons, statistically significant associations were identified between G1A of situation A and G1A of situation B, as well as G2D1 and G3D2; between G2D1 and all the groups in situation B; between G3D2 of situation A and G3D2 of situation B, and between G4D3 and G2D1 as well as G4D3 of situation B.

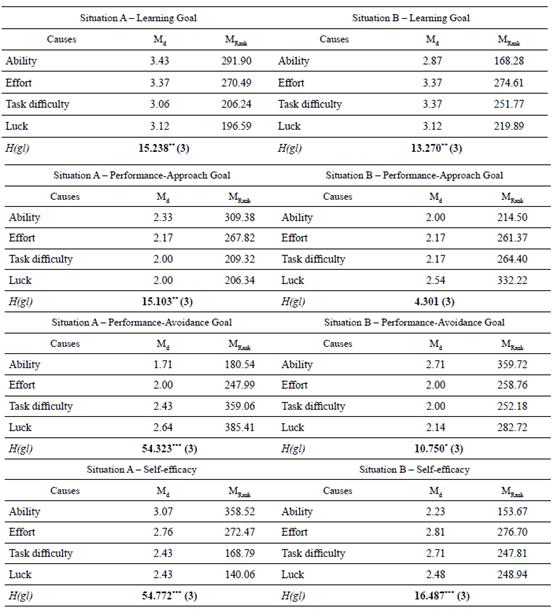

Table 3 shows the comparison of groups concerning achievement goals and self-efficacy for reading comprehension due to the causes attributed by the students in situations A and B of the EAC-CL. Statistically significant comparisons of groups in situation A: learning goal, in the comparison between task difficulty and ability (z = 3.258; p < .01; r = .31), task difficulty and effort (z = 3.340; p < .01; r = .16); performance-approach goal: ability and task difficulty (z = 3.340;p < .01; r = .32); performance-avoidance goal: ability and task difficulty (z = -5.959;p < .001; r = .57), ability and luck (z = -4.607;p < .001; r = .45), ability and effort (z = -2.705;p < .05; r = .13); effort and luck (z = -3.585;p < .01; r = .18), effort and task difficulty (z = -2.705;p < .05; r = .13). Self-efficacy: ability and task difficulty (z = 6.316; p < .001; r = .61), effort and task difficulty (z = 5.241; p < .001; r = .24), ability and luck (z = 4.899; p < .001; r = .65), effort and ability (z = 3.441; p < .01; r = .16).

Table 3 Comparisons of Motivational Constructs with EAC-CL Causes

Legend. M d = Median; M k = Rank Means.

Note. Values in bold indicate statistically significant comparisons, ***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05.

For situation B of the EAC-CL, statistical significance was verified in the comparisons between the causes indicated by the students and the Learning Goal and the Performance-Avoidance Goal factors of the EMR-CL. Statistically significant results (see Table 3), learning goal: effort and ability (z = -3.370;p < .01; r = .18); performance-avoidance goal: task difficulty and ability (z = 3.218; p < .01; r = .23), ability and effort (z = 3.112; p < .05; r = .17). No statistical significance was identified for the performance-approach goal and the causes of situation B. Regarding self-efficacy, differences were obtained between effort and ability (z = 3.781;p < .001), and task difficulty and ability (z = 2.808; p < .05) - both with r = .20. The effect size of the comparisons involving the two EAC-CL situations ranged from very small to small.

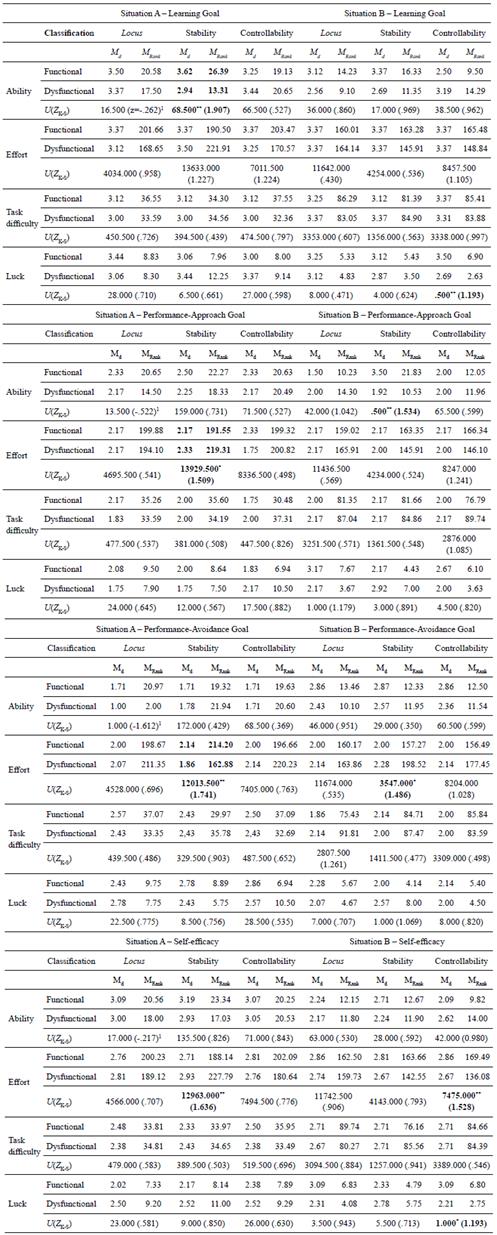

Table 4 shows the comparison of groups involving achievement goals and self-efficacy for reading comprehension according to the classification of the psychological dimensions of the causal attributions ability, effort, task difficulty, and luck in situations A and B of the EAC-CL. Statistically, significant comparisons in Situation A were identified in the psychological stability dimension (functional/dysfunctional) involving the learning goal: ability, r = .30; performance-approach goal: effort, r = .08; performance-avoidance goal: effort, r = .09 and self-efficacy: effort (stable) and effort (unstable), r = .08.

Table 4 Comparisons of Motivational Constructs with the EAC-CL Classification of Psychological Dimensions

Legend. M d = Median; M ranks = Rank Means.

Note. Values in bold indicate statistically significant comparisons, ***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05.

Table 4 also shows the comparisons that presented statistical significance in situation B, considering the classification of the psychological dimension stability into functional and dysfunctional in the performance-avoidance goal: ability (stable cause), r = .32; effort, r = .08; and in self-efficacy: luck, r = .40. About the psychological controllability dimension, statistically significant differences were identified in the learning goal for luck, r = .40, and in self-efficacy for effort, r = .09. The effect size of the comparisons involving the two EAC-CL situations ranged from very small to small.

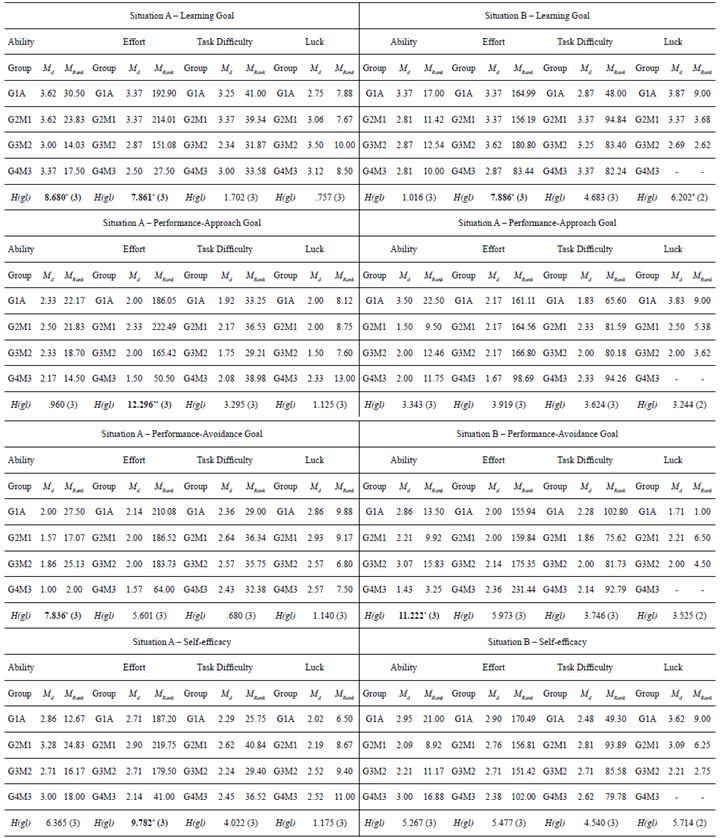

Finally, Table 5 compares motivational constructs considering the four groups of causal attributions (adaptive/maladaptive). Focusing on situation A, differences in the learning goal in the groups were linked to the causes of ability and effort; however, the pairwise comparison was not statistically significant. In the performance-approximation goal, in turn, statistical significance was identified between G2D1 and G1A (z = -3.064; p < .05; r = .15). There were differences in the performance-avoidance goal and the causality attributions linked to ability; however, the pairwise comparison did not present statistical significance. There were differences between G2D1 and G4D3 (z = 4.062; p < .001; r = .27); G2D1 and G3D2 (z=3.900; p < .001; r = .24); and G2D1 and G1A (z = -3.111; p <.01; r = .15) considering the attribution to effort for self-efficacy. In turn, in the attribution to effort in situation B of the EAC-CL, there was a statistically significant difference in the learning goal between G3D2 and G4D3 (z = 2.693; p <.05; r = .19); in the attribution to ability, the performance-avoidance goal was different between G3D2 and G4D3 (z = 3.230; p <.01; r = .23). Comparisons involving self-efficacy were statistically insignificant. In situations A and B of the EAC-CL, the effect size of the comparisons was small or very small.

Table 5 Comparisons of Motivational Constructs with Groups Obtained by EAC-CL

Legend. G1A = Adaptative Group; G2M1 = Maladaptive Group - One Dysfunctional Cause; G3M2 = Maladaptive Group - Two Dysfunctional Causes; G4M3 = Maladaptive Group - Three Dysfunctional Causes; M d = Median; M Rank = Rank Means.

Note. Values in bold indicate statistically significant comparisons, ***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05.

Discussion

The results of stage 1 demonstrated that the EAC-CL presents evidence of content validity, which alludes to the representativeness of its content considering the evaluated construct (AERA et al., 2014). The expert judges and students corroborated students usually attribute explanations that refer to ability, effort, task difficulty, and luck in situations of success and failure in reading comprehension and that these causes are associated with the three psychological dimensions locus, stability, and controllability (Almeida & Guisande, 2010; Graham, 2020; Weiner, 2010).

The results obtained in stage 2 prove that the EAC-CL presents evidence of validity based on its internal structure. Regarding the association between the four attributed causes and the three psychological dimensions for situations A and B of the EAC-CL, in a good performance in reading comprehension scenario, effort, task difficulty, and luck were associated with locus and controllability. In the context of doing poorly in this cognitive-linguistic skill, effort and task difficulty were related to controllability. This result indicates that the connection between attributed causes and psychological dimensions can demonstrate students' notions of responsibilities and merit regarding success and failure (Almeida & Guisande, 2010; Ferraz et al., 2020). The fact that associations between ability and psychological dimensions are identified in situations of success and failure can indicate the students' inaccuracy in their evaluation. Students may perceive ability as less stable and uncontrollable, depending on their beliefs and the context in which they live (Graham, 2020).

Concerning the associations between the causes attributed in situations A and B, only 'effort' showed correspondence for success and failure in reading comprehension. This result may be linked to teachers' feedback, which often emphasizes the role of effort to demonstrate students' competence to good results and warn them about the lack of commitment in the context of failure (Graham, 2020; Mahmoodi & Karampour, 2019). The other associations between the causes attributed in the two situations suggest a lack of recognition of the students' self-perceived competencies to do well in reading comprehension (attribution to task difficulty and luck in situation A) and, at the same time, to responsibilities for failure (attribution to ability and effort in situation B). This result can indicate the school/family climate's impact on how students attribute the causes for positive and negative results (Almeida & Guisande, 2010; Graham, 2020). It was also found that some students indicated effort in Situation A of the EAC-CL, while failure was attributed to ability in situation B. In this case, despite the similarity between both causes regarding the internal locus, the students seem to be more responsible for success than failure, as ability is seen as a more stable and less controllable cause, while effort is unstable and controllable (Graham, 2020; Weiner, 2010).

Statistically significant associations were found only to classify the psychological dimension of controllability (functional/dysfunctional) in situations A and B of the EAC-CL. This result suggests that associating the level of control with the cause to justify success or failure seems more accessible to students than indicating the locus and stability of the cause. In Boruchovitch and Santos (2016), for example, controllability and locus were identified on a scale to assess causal attributions for failure and success in general academic situations; however, the presence of stability was not evident.

Concerning the four groups of causal attributions,1 we identified correspondence between the more and less adaptive belief patterns. However, there were associations between adaptive attributions for success in reading comprehension and maladaptive attributions for failure and vice versa. This result indicates that there may be an attributional pattern for success and failure, as indicated by Almeida and Guisande (2010) and Weiner (2010). However, how each of these results is understood by students also involves their background (e.g., academic performance, history of repetition) (Graham, 2020; Ferraz et al., 2020) and the way they are dealt with in the family and school context, particularly by teachers (Graham, 2020; Wolters et al., 2013). In this sense, Schunk (1994) indicated that motivational quality is not a trait but a changeable and context-sensitive component.

In stage 3 of this study, the results indicate validity of the EAC-CL based on the relationship with other variables. The statistically significant indices from the comparison of groups involving achievement goals and self-efficacy for reading comprehension due to the four attributional causes in situations A and B of the EAC-CL and the classification of the psychological dimensions (functional/dysfunctional) corroborate the linking of the causal attributions with the motivational constructs (Ferraz et al., 2020; Schunk, 1994; Vezzani et al., 2018; Wolters et al., 2013; Zimmerman & Risemberg, 1997). In turn, results indicate the attributional pattern (adaptive/maladaptive) is also associated with the motivational quality of students (Almeida & Guisande, 2010; Graham, 2020; Weiner, 2010).

In achieving goals, results indicate attributions to effort and ability connected with the learning goal, which extends to the pattern of attributional beliefs (adaptive/maladaptive) and the classification of the psychological stability dimension directed toward ability. Effort and ability reflect greater responsibilities of students for their performance and are consistent with the characteristics of the learning goal (Bardach et al., 2020; Ferraz et al., 2020; Urdan & Kaplan, 2020). The effort, characterized as internal, unstable, and controllable, is mainly linked to the maintenance of motivation, especially when the educational context supports the adequate management of negative results, such as when teachers provide feedback that enables students to learn from their errors (Mahmoodi & Karampour, 2019).

In situation A of the EAC-CL, attribution to ability stood out in the orientation by the performance-approach goal and the classification of stability linked to effort. However, a higher frequency of this achievement goal was observed in the maladaptive group for effort (one dysfunctional dimension) compared to the adaptive group. Students guided by this goal commonly present good academic performance. Nevertheless, this study indicates that there may be a less adaptive attributional pattern concerning the conception of the effort (Urdan & Kaplan, 2020). This study also demonstrated no effect in comparing the performance-approach goal with the causes and psychological dimensions of the reading comprehension failure situation. This result converges with the principle that the focus on achieving success prevails in the performance-approach goal (Bardach et al., 2020; Urdan & Kaplan, 2020).

Lower adherence to the performance-avoidance goal was attributed to the ability for situations A and B of the EAC-CL. This association was observed in the comparison effect of the causal attribution groups (adaptive/maladaptive). This result may be related to the self-concept in reading comprehension and causal attributions, which acts as a protective factor against characteristics of the performance-avoidance goal that are harmful to motivation, such as, for example, low perception of competence (Ferraz et al., & 2020; Urdan & Kaplan, 2020). A discrepancy was found in the classification of effort regarding the stability of success and failure. This result is an indication of possible relationships between expectations about the future in attributing effort with the specificities of the performance-avoidance goal - low expectations regarding the achievement of good results in reading comprehension and high expectations about failure (Ferraz et al., 2020; Graham, 2020; Wolters et al., 2013). It should be emphasized that the controllability psychological dimension did not affect the performance-avoidance goal in situations A and B and the locus in situation A. This result reinforces the assumption that this achievement goal interferes with the level of responsibility for failure and the attribution of merit for success (Bardach et al., 2020; Urdan & Kaplan, 2020).

Finally, the attribution to ability demonstrated a higher level of self-efficacy, given success in reading comprehension compared to task difficulty and luck. However, self-efficacy stood out in attributing effort compared to ability in situations of success and failure in reading comprehension. In addition, the attribution to task difficulty had a higher self-efficacy level when contrasted with ability in situation B. This result indicates that self-efficacy beliefs are linked to causal attributions underlying good performance, as in the case of effort, followed by ability (Frijters et al., 2018; Graham, 2020; Vezzani et al., 2018). However, this perception can become less concise in failure situations, given the attribution of the particularities of the tasks requiring reading comprehension (Yau, 2021).

Another aspect identified in situation A was that the attribution of effort had the psychological dimension stability qualified as dysfunctional, associated with a higher level of self-efficacy than in the functional classification. Furthermore, as expected, the maladaptive group (one dysfunctional psychological dimension) scored higher in self-efficacy than the other groups categorized as maladaptive. However, the adaptive group had lower self-efficacy for reading comprehension than the maladaptive group (one dysfunctional psychological dimension). Schunk and Usher (2013) discuss the role of self-efficacy in SRL to sustain student motivation, even when faced with complications. It is assumed that this proposition can also be expanded, encompassing the inherent function of stability associated with self-efficacy in maintaining motivation to create positive expectations concerning reading comprehension. In Situation B of the EAC-CL, the functional classification of controllability for attributing effort and luck when faced with failure in reading comprehension showed greater self-efficacy. Despite being functional, it is considered that the qualification of luck may indicate a movement of avoidance to preserve the academic self-concept regarding negative results, which may be a factor that keeps students' level of self-efficacy high (Clem et al., 2018; Faber, 2019).

As a limitation, there is a possibility that the restricted number of participants in forming the groups interfered with the study results (e.g., type II error in the comparisons that did not show statistical significance). This hypothesis is based on the reduced effect size values from the statistically significant results. Additionally, sample N did not allow for more robust analyses to be performed to identify, for example, the latent profiles of the causal attributions associated with the psychological dimensions or the use of decision trees to assess the relationships between the intrapersonal causal attributions of the students for reading comprehension and motivational constructs present in SRL. Therefore, it is suggested that future studies expand the sample quantitatively and include students from other locations in Brazil. Other constructs included in the SRL process, such as learning strategies, time management, self-monitoring, and positive and negative self-reactions, should be evaluated. Considering those processes to assess their associations with intrapersonal causal attributions would deepen the investigation of the causes and psychological dimensions linked to 'ability' and 'effort.'2

Final Considerations

This research achieved the objective of verifying the validity evidence for the EAC-CL. As expected, the causes of ability, effort, task difficulty, and luck were recognized as the causal attributions commonly pointed out by Brazilian students for reading comprehension performance, linked to the three psychological dimensions of locus, stability, and controllability. However, it is observed that there are some differences when comparing the functioning of these dimensions in situations involving success and failure in reading comprehension, emphasizing the level of accountability and the perception of merit. Finally, the relationships identified between the attributions of causality with self-efficacy and achievement goals denote the underlying particularities in the functioning of these motivational constructs in the context of reading comprehension. Thus, the results of this research can contribute both to the process of evaluating causal attributions and to the delimitation of intervention programs aimed at the motivation for reading carried out from the careful investigation of this construct.