Introduction

Suicidal Ideation among adolescents is a major concern all over the world (Creemers et al., 2012; Mitsui et al., 2014; Rasmussen et al., 2018). Longitudinal studies also suggest that Suicidal Ideation increases during adolescence (Fergusson et al., 2000; Kerr et al., 2008).

Previous studies suggested strong connections between low self-esteem and Suicidal Ideation and suicidal attempts (Bhar et al., 2008; Thompson, 2010; Wild et al., 2004). More specifically, a deficit in self-esteem in relation to suicidal behaviour has remained a particular focus of attention among researchers. It is suggested that youth with low self-esteem develop Suicidal Ideation as a way to escape from the distressing emotions that are related to their negative self-evaluation. Particularly, negative self-evaluation has been identified as a significant factor in developing Suicidal Ideation among adolescents (Bhar et al., 2008; Fergusson et al., 2003; Rasmussen et al., 2018; Thompson, 2010).

A study was conducted to assess the hopelessness, and meaning in life in clinical sample of 150 patients with different diagnosis of mental disorders. Majority of the sample was comprised of female patients (n =126). Most of the patients (58%) had history of suicidal attempts and had self-injured (58%). They found that those patients who attempted suicide exhibited hopelessness than the patients who had self-injurious behaviour (Pérez Rodríguez et al., 2017).

O’Connor (2018) suggested three stages of suicidal behaviour: pre-motivational, motivational, and volitional. In pre-motivational stage, individuals become stressed out due to personal and environmental factors which increase the risk of his suicidal behaviour. During motivational stage, individuals form their Suicidal Ideation without any intent while in volitional stage, individuals act upon Suicidal Ideation and intent. Studies showed evidence that low self-esteem increase Suicidal Ideation both during adolescence (Wild et al., 2004) and young adulthood (Bhar et al., 2008; Jang et al., 2014).

Theoretical model of suicidal behaviour (Baumeister, 1990; Baumesiter & Vohs 2007) suggested that presence of Suicidal Ideation is related to intense negative feelings such as feeling hopelessness and unwanted. An individual interprets himself as a failure in society.

Ideal self and actual self are the terms defined by psychologists to explain the personality domain of the individual. Actual self refers to the actual personality of a person and ideal self refers how a person wants to be. Ideal self is an idealized image that a person develops over the time, based on what they have learned and experienced. Some researchers suggested that discrepancy between ideal self and actual self is a central cause in developing Suicidal Ideation. In contrast, Franck and his colleagues (2007) suggested that the size of discrepancy between ideal and actual self is crucial for initiating the Suicidal Ideation. It is further suggested that when an individual’s self-esteem is threatened, he develops feelings of failure that initiate suicidal process (Crocker & Park, 2004).

Erik Erikson’s (1968) Psychosocial Developmental Theory proposed that during the stage of “identity verses role confusion”, adolescents who resolved the process of ego formation in a way that made them capable to face the challenges of intimacy, lived by their own standards and regulate their self-esteem. Inversely, those adolescents who remain unsuccessful to resolve the challenges of life are incapable of regulating self-esteem. Therefore, they entered into adulthood without consolidated identity and may develop premature identity or may have been unable to engage in any form of identity formation and remain in a state of identity diffusion (Kroger & Marcia, 2011). To reduce this distress and maintain self-worth, they need social support (Mackin et al., 2017) and are dependent on the approval of significant others (parents, teachers, and friends) to balance their self-esteem. If parents, teachers, and friends could not provide proper emotional support, then they may develop crises that subsequently lead towards the development of Suicidal Ideation.

A study was conducted by Wild and colleagues (2004) to investigate the influence of self-esteem on suicidal behaviour among grade 8 and 11 students (sample size, N = 939) in Cape Town, South Africa by using the techniques of Multinomial Logistic Regression. Results revealed that low self-esteem was significantly associated with suicidal behaviour and attempts.

Another study was conducted in Japan to investigate the role of self-esteem in the development of Suicidal Ideation among students (N = 30) aged between 18 and 26 years old. The study found self-esteem as an important contributory factor in the development of Suicidal Ideation among young adults (Mitsui et al., 2014).

Similarly, a study was conducted to assess low self-esteem, depression, and hopelessness as risk factors for developing suicide ideation among adult psychiatric patients (N = 338). The study found poor self-esteem as an important risk factor for Suicidal Ideation even after controlling depression and hopelessness (Bhar et al., 2008).

Previous studies have been conducted to assess the link between self-esteem and suicidal ideation by considering self-esteem as unidimensional approach, while present study examines the role of self-esteem in the development of suicidal ideation by considering two dimensions of self-esteem: positive and negative in Pakistani undergraduates.

Method

Participants

The sample of the present study was comprised of 600 undergraduates enrolled from the different Government colleges and universities in Peshawar a city in province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) Pakistan. Only those students were included in the sample that were studying 4 years BS Program and were unmarried. Half of the sample consisted of males (n = 300) and half females (n = 300) aged between 17 to 25 years (M = 20.26, SD = 1.6). Most of them were brought up in both-parent homes (91.5%). 55.3% were belonging to rural whiles 44.7% were from urban areas. Results further revealed that 50.5 % students were from lower, 46.5 % from middle, and only 3% from upper class.

Students suffering or previously suffered from any mental and physical disability were excluded from the study.

Procedure

The present research was approved by the Advanced Studies Review Board (ASRB) of Shaheed Benazir Bhutto women University Peshawar Pakistan for Ethical Approval. Different colleges and universities of Peshawar were visited to collect the data. Permission for data collection was taken from the authority figures of concerned departments by using random sampling technique. Prior to start of study, informed consents were taken from participating students. All the participants were assured that nobody will have access to the data except the researcher and it will be used only for research purposes. All respondents voluntarily participated and they were permitted to quit at any point. Two scales along with the demographic sheet were distributed among the students. The selected participants were debriefed about the study. A demographic sheet was used to collect the information related to the age, gender, location, and socio economic status.

Research Instruments

Suicidal Ideation Scale (SIS;Rudd, 1989). Suicidal Ideation Scale (SIS) was used to collect the data. The scale consisted of 10 items using five point Likert scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”.Urdu translated version of SIS was used in the present study which has already been used by author (see Shagufta et al., 2019). The Cronbach alpha of SIS was found very high (a = .86) in the previous study (Rudd, 1989).

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES; Rosenberg, 1995). Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) is commonly used scale to measure the positive and negative self-evaluations. Initially, the scale was designed to assess the self-esteem of adolescents but now the scale has been implemented on a wide range of age groups. RSES was proposed to investigate the positive and negative views of ones self. The scale consists of total 10 items including five items assessing positive and five items negative self-esteem. Five of the statements are reversely scored to avoid response biases. Five points Likert Scale is used to assess the items ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. The reliability of Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale was high (a = .91).

Statistical Analysis

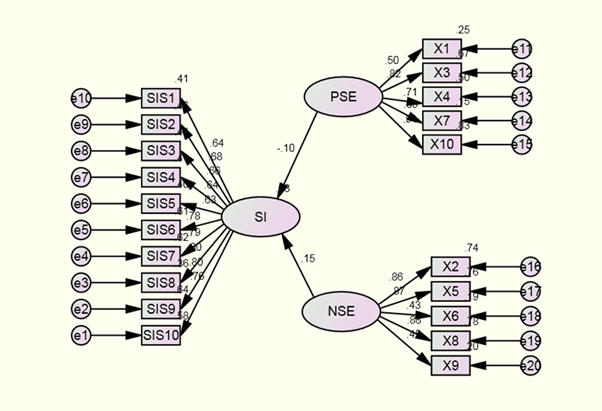

The proposed model was assessed by using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) techniques. The data was analysed by using software Amos 18. SEM is a combination of factor analysis and path analysis and Bentler (1986) had also used SEM techniques to assess data. SEM is the most appropriate technique to assess the relationship between observed variables and latent constructs (Weston et al., 2008). SEM analysed the data both on measurement level and structural level simultaneously. On measurement level, all the factor loadings were assessed, and on structural level, relationships have been found among latent constructs. Current model was specified with three latent variables including Suicidal Ideation and two factors of Rosenberg Self-esteem scale: positive self-esteem and negative self-esteem.

Results

SPSS 19 was used for the analysis of descriptive statistics. Structural Equation Modeling techniques were utilized to assess the factor loadings of both SIS and RSES and relationship between latent variables. The models were specified and estimated using Amos 18. On measurement level, a signal factor model of SIS and two-factor model of the RSES have found adequately fit to data. On structural level, relationship between latent variables has been found.

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics (Table 1) shows Mean, Standard Deviation and Cronbach’s Alpha reliability (Cronbach, 1951) for subscales of RSES and SIS. The reliabilities of the scales have been assessed through the traditional measures of Cronbach Alpha. The results of current study shows that SIS is highly reliable (a = .90) scale among students population. Results also demonstrated that RSES is highly reliable among students: positive self-esteem (α = .70) and negative self-esteem (α = .71) and total self-esteem (a = .70).

Table 1 Mean Standard Deviation and Cronbach’s Alpha for Suicidal Ideation Scale, Positive Self-Esteem, and Negative Self-Esteem and Self-Esteem Scale Total

| Variable | M | SD | Range | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicidal Ideation Scale(SIS) | 14.11 | 6.23 | 9-50 | .90 |

| Positive Self-Esteem (PSE) | 14.00 | 5.44 | 5-63 | .70 |

| Negative Self-Esteem (NSE) | 13.46 | 5.19 | 5-70 | .71 |

| Self-Esteem Scale Total (SEST) | 27.5 | 8.32 | 10-82 | .70 |

Table 2 shows the standardized and unstandardized factor loadings with standard error on both measurement and structural levels. At measurement level, the adequacies of the factor loadings were assessed for latent variables of Suicidal Ideation and two factors of Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) techniques are used to assess the factor structure and factor loadings of measured variables and to determine that data fit to the pre-established model. Values of Comparative Fit Index (CFI; Bentler, 1990) and Tucker Lewis Index (TLI; Tucker & Lewis 1973) should be above than .95 for excellent model fit. However, value above than .90 is acceptable for adequate model. Values of Root Mean Square Residual (RSMR) and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RSMEA; Steiger, 1990) should be < .05 for excellent model; however, values < .08 are acceptable. Current CFA analysis revealed satisfactory fit of overall model (χ2 = 569.8, df = 169, p > .001; CFI = .92; TLI = .91; RMSEA = .05; SRMR = .06). The adequacy of the model was further supported by factor loadings. All items are showing statistically significant factor loadings (p < .001). According to Hair et al., (2012) CFA standardized factor loadings should be 0.6 or higher because it indicated that half of the variance in the observed variable are explained by the latent variable, however, .40 is acceptable. Present results are in line with Hair et al.’s (2012) suggestions. Results also indicates that those students who had negative self-esteem were more prone towards Suicidal Ideation (β = .15, p < .001). The structural level analysis also indicated that those students who were high on positive self-esteem exhibited less Suicidal Ideations (β = -.10, p < .05).

Table 2 Standardized and Unstandardized Regression Paths (with standard errors) for the Specified Measurement Model and Structural Model (N=600)

| Item | B | β | SE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement Level | |||

| Suicidal Ideation Scale | |||

| 1. I have been thinking of ways to kill myself. | 1.00 | .64*** | .05 |

| 2. I have told someone I want to kill myself. | 1.00 | .67*** | .06 |

| 3. I believe my life will end in suicide. | .72 | .66*** | .04 |

| 4. I have made attempts to kill myself. | .83 | .63*** | .05 |

| 5. I feel life just isn’t worth living. | 1.00 | .63*** | .06 |

| 6. Life is so bad I feel like giving up. | 1.00 | .78*** | .05 |

| 7. I just wish my life would end. | 1.00 | .78*** | .05 |

| 8. It would be better for everyone involved if I were to die. | .94 | .60*** | .06 |

| 9. I feel there is no solution to my problems other than taking my own life. | 1.00 | .80*** | .04 |

| 10. I have come close to taking my own life. | 1.00 | .76*** | .04 |

| Positive Self-Esteem | |||

| 1. On the whole, I am satisfied with myself. | 1.00 | .50*** | 01 |

| 2. I feel that I have a number of good qualities | 0.80 | .81*** | 07 |

| 3. I am able to do things as well as most other people. | 0.96 | .70*** | .01 |

| 4. I feel that I’m a person of worth, at least on an equal plane with others. | 0.91 | .60*** | 07 |

| 5. I take a positive attitude toward myself. | 1.00 | . 91*** | 01 |

| Negative Self-esteem | |||

| 1. At times, I think I am no good at all. | 1.00 | .86*** | .01 |

| 2. I feel I do not have much to be proud of. | 1.00 | .87*** | .04 |

| 3. I certainly feel useless at times. | 1.00 | .43*** | .08 |

| 4. I wish I could have more respect for myself. | 1.00 | .88*** | .03 |

| 5. All in all, I am inclined to feel that I am a failure. | 1.00 | .49*** | .07 |

| Structural Level | |||

| Negative Self-Esteem Suicidal Ideation | 0.11 | .15*** | .03 |

| Positive Self-Esteem Suicidal Ideation | -0.06 | -.10* | .02 |

Note: χ2 (169) =569.8p < .001; CFI = .92; TLI = .91; RMSEA = .05; RSMRS = .06

Discussion

The aim of the study was to explore the self-esteem and suicide ideation in Pakistani Undergraduates. For this purpose, SEM model was specified including suicidal ideation and two factors of Rosenberg Self-esteem scale (positive self-esteem and negative self-esteem). Previous studies have been utilized RSES as unidimensional model but current study has found empirical support for two-factor model exhibited from factor loadings and fit indices mentioned in Table 3.

Cronbach alpha was used to assess the internal consistencies of two scales. In the current study, SIS exhibited good reliability (a = 90). Furthermore, two subscales of RSES also showed good reliabilities: positive self-esteem (a = .70), and negative self-esteem (a = .71).

Results revealed that those students who had more negative self-esteem reported more Suicidal Ideation which indicates that negative self-esteem is a prominent factor in developing Suicidal Ideation. Previous studies that were cross-sectional in nature, had also found strong relationship between low self-esteem and Suicidal Ideation.

Rasmussen et al. (2018) found that those individuals who feel that they are invaluable, unworthy and inadequate are more prone towards suicidal behaviour.

Present results are also consistent with the previous study Mitsui et al. (2014) who suggested that individuals who negatively evaluate themselves and having lack of respect for themselves exhibit Suicidal Ideation tendencies.

Present results are also in line with Grøholt et al. (2005) who found that those adolescents who negatively evaluate their own competencies and are unable to stabilize their self-concept are more likely develop Suicidal Ideation than those who have positive self-esteem.

McGee et al. (2001) provide some support for current study that individual characteristics such as low self-esteem and feelings of hopelessness elevate the risk of Suicidal Ideation in early adulthood.

Present study indicated that those students who were high on negative self-esteem were more prone towards the development of Suicidal Ideation. Furthermore, present study found that positive self-esteem is a buffer against Suicidal Ideation. It is believed that those individual who develop suicidal crises need to work on their self-concept and try to find their own standards for further life. Preventive strategies should focus on regulating positive self-esteem to make them able to handle their pain and regulate their emotions.

In the present study, two-factor model of RSES has been found more appropriate as assessed by Boduszek et al. (2013) and Shagufta et al. (2019), however; few studies have used the scale as unidimensional (Nguyen et al., 2019; Wilburn & Smith, 2005). In the present study, males and females participants were equally distributed, while previous studies have shown females predominance (Nguyen et al., 2019; Pérez Rodríguez et al., 2017; Wilburn & Smith, 2005).

Current study was focused only on self-esteem without controlling loneliness and hopelessness to assess Suicidal Ideation among students. It is suggested that loneliness and hopelessness are important prognostic signs among suicidal adolescents and, therefore, important factors to take into account while assessing Suicidal Ideation.

Second limitation of the study is cross-sectional data. Longitudinal study may provide better understating of Suicidal Ideation and behaviour over a period of time.

Third limitation is related to obtaining data related to Suicidal Ideation by using self-report measure. For future studies, in-depth interviews with closely connected informants as well as suicide notes are warranted.