1. Introduction

One of the research priorities proposed by the American Marketing Association in the 2014-2016 period was proving the value of marketing management in organisations (Marketing Science Institute, 2014). The global competitiveness index presented by the World Economic Forum (2018) showed that among private and governmental organisations managers in Colombia, there is a perception of a greater intensity of competition, a greater degree of consumer orientation and greater interest by differentiation; these issues encourage the implementation of marketing actions and therefore motivate the continuous improvement of marketing processes.

One of the most important marketing elements is investment in advertising, which is expected to increase to $630 billion worldwide by 2018. Therefore, optimal management of advertising resources is a key metric for organisations to use in evaluating marketing performance. Following this perspective, academic research on advertising has mainly focused on showing (1) the decisive factors of advertising effectiveness among the audience; and (2) ways to facilitate organisational decision-making related to resource allocation (Eisend and Tarrahi, 2016; Hutter and Hoffmann, 2014; Kim and Han, 2014; Ortiz-Rendón and Moreno, 2017).

Furthermore, in a less generalised form, another research line aims at explaining how advertising management processes are carried out and how theoretical advertising models influence decisions. For example, Gabriel, Kottasz and Bennett (2006) examine the degree to which account planners use theoretical models to assess how advertising works. Their results show that the differences between the models used by advertising agencies and the theoretical models stem from resource constraints, time pressure and lack of well- trained staff. In the Colombian case, it is argued that the creative identity required for advertising campaigns remains underdeveloped due to the commercial characteristics of the advertising industry, the economic difficulties experienced by the population and the country's social conflict (Roca, Wilson, Barrios, Muñoz-Sánchez, 2017).

It has also been shown that the advertising management carried out by advertising agencies and organisations focuses on attaining optimal levels of creativity in their campaigns (Behboudi, Hanzaee, Koshksaray, Tabar and Taheri, 2012; Hill, 2006) rather than on relating the impact evaluation of the designed advertisements; this reflects a tendency to base their decisions on basic advertising theories and results obtained during previous campaigns. The consequences of not taking advantage of lessons learned are evident in the academic literature (Brennan and Vos, 2013; Nyilasy and Reid, 2009).

Process management is an essential task for organisations because it improves internal efficiency and changes how they function (Shtub and Karni, 2010). In the particular case of advertising, improved management will lead to attainment of the expected results and allow decisions to be made based on more reliable information during the IMC process; this will integrate the brand's strategic management, audience definition, communication channels and result assessment (Kliatchko, 2005). In addition, by studying marketing communications' management along with its objectives, results, and the role of organisations (Christensen, Firat, Torp, 2008; Einwiller and Boenigk, 2012; Smith, 2012) can create new opportunities for IMC such that academics and professionals can increase the effectiveness of their promotional activities (Patti, Hartley, Dessel, Baack, 2017).

As the above discussion, illustrated, little evidence exists about how organisations manage their advertising activities. This is further demonstrated by the fact that the research units of analysis are mainly the audience and the advertising agencies (Kim, Hayes, Avant, Reid, 2014); such researches tend to overlook advertiser organisations' perceptions, which play a fundamental role in investment decisions.

Finally, t given that few studies have examined how companies manage their advertising campaigns, it is therefore necessary to analyse this process. Accordingly, this paper aims to analyse how the conduct of advertising planning marketing managers is influenced by factors such as types of consumer responses, measurement methods used and expected results among Colombian Companies.

This article is structured as follows, the first section overviews the theoretical framework on advertising management and presents the approach of five research hypothesis. The second section details the exploratory empirical methodology based on conducting a telephone questionnaire with 150 marketing managers at medium and large companies in Colombia. Third, the results are presented. The results are then discussed and the managerial implications of the research are presented.

1. Advertising management

The relation between advertising and marketing is determined by how integrated marketing communications are managed and carried out. Integrated marketing communications (IMC) is defined as an audience-driven organisational process to strategically manage the stakeholders, content, channels and results of brand communication programmes (Kliatchko, 2008). IMC is also seen as a planning process to strategically assess a company's communication elements and determine the best way to integrate them into the company. IMC plays a decisive role in helping establish relationships with customers and other interested parties by creating favourable perceptions, attitudes, and behaviours towards brands (Reid, 2005).

Advertising is a crucial component of IMC, and its role varies according to the organisation's business model, product and marketing objectives. Changes in communication systems and the marketplace (Schultz and Patti, 2009) can also affect it. For instance, advertising can have a central focus of communicating a brand while other components such as commercial promotion and personal sales, occupy a secondary place. Therefore, advertising must be consistent with the IMC programme to ensure that the organisation transmits a clear message to its target audience. IMC is a multidimensional concept (Kliatchko, 2008; Low, 2000; Porcu, Del Barrio-García, Kitchen, 2012) that unifies communications to relay a consistent message and image and considers advertising as a tool of communication. Accordingly, there are constructs that explain how IMC is carried out in terms of advertising management.

The ICM process starts with planning (Duncan and Moriarty, 1997; Porcu et al., 2012; Reid, 2005). Planning integrates several stages, such as defining the announced objective. This aspect determines which product or service the campaign will be developed for, who the target audience will be, to whom the campaign or advertisement will be directed, what relationship exists among audiences, the brand name relevance, channels and price, among others. The organisation's economic capacity is the second aspect and determines the allocation of financial resources to the campaign. The selection of advertising professionals to implement the advertising campaign is another stage. These professionals serve as the link between the organisation and target public and are responsible for designing an effective message that meets the previously established advertising objectives. Finally, the media outlets are chosen based on the advertising campaign's target profile and objectives.

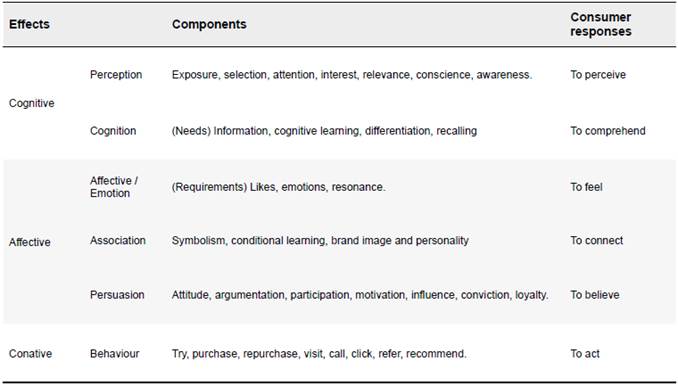

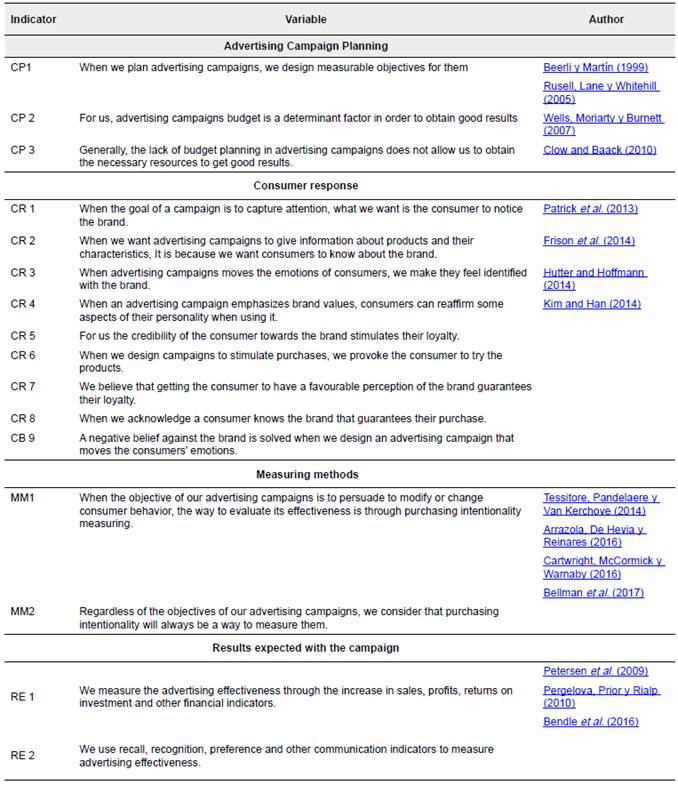

When an advertising campaign has a clearly defined scope, the expected response typologies from consumers, e.g. cognitive, affective and/or conative, can be determined in detail (Pickton and Hartley, 1998; Vakratsas and Ambler, 1999). As indicated in Table 1, the impact on the audience is created in various ways without a hierarchical order necessarily being present. That is, the message can influence perception, cognition, persuasion and behaviour. For example, a message can create awareness, provoke an emotion and link a product to a lifestyle, which means that it created a perception and had affective and association effects. All may be equally effective but influence the consumer differently.

Methods for measuring advertising effectiveness are defined according to the types of expected response (Kliatchko, 2008). Methods to measure advertising effectiveness are classified according to campaign development stage and type of response expected from the target audience. There are two development stages: pre-testing and post-testing. The first evaluates the audience comprehension of the message before it is transmitted (diagnosis); the second stage measures advertising effectiveness after the message has been announced (evaluation). Post-test and measurement methods based on the type of response expected from the target audience are used after the message has been transmitted to evaluate the scope of the objectives set and propose adjustments for future advertising campaigns.

Organisations' expectations regarding the outcomes of advertising campaigns can vary, as can the means of assessing these outcomes (Porcu et al., 2012; Schultz and Schultz, 1998). One main evaluation indicator is sales. Activities such as direct marketing campaigns, campaigns to attract target audiences to selling premises and brand awareness campaigns, desired short-term effects include increased sales or market participation. These measures can thus be appropriate to measure an advertising campaign's success. However, such outcomes should be assessed in recognition that they reflect other factors as well, such as price, distribution, competition, product, changes in buyer needs and the target audience's preferences. Another expected assessment metric is return on investment in advertising (ROI). Spending share is an assessment method that compares the product's market share and investment share with that of the competition (Petersen et al., 2009).

Other outcomes are non-financial. These are based on the effects of the communication and allow analysis of the different stage's consumers go through, from the moment of exposure to an announcement through to expressing the expected reaction (Petersen et al., 2009). Assessment of non-financial objectives can include understanding how the advertisement impacted brand validation, brand image, and target audience attitude towards the brand, which then leads to assessment of audience purchase intent and the uses of this, as well as whether an advertisement should be recalled.

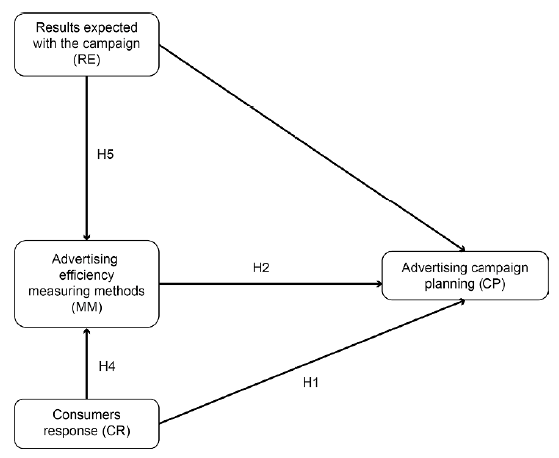

On the basis of this review, four dimensions were identified: advertising campaign planning (CP), consumer response (CR), advertising effectiveness measuring methods (MM) and results expected from the campaign (RE).

2. Hypothesis

Based on (1) the role that marketing managers assume when managing resources and (2) the importance of improving organisational processes, IMC's results are a key element organisation should consider when making decisions regarding advertising investments (Porcu et al., 2012; Reid, 2005). Outcomes are a pillar of IMC, which is focused on evaluating (1) the effects on consumers and their responses and (2) the financial results that influence the organisational results (Kliatchko, 2008; Patti et al., 2017; Tafesse and Kitchen, 2017). Assuming a financial orientation for measuring advertising, outcomes leads an organisation towards the design of metrics that provide greater certainty when deciding the future allocation of scarce resources and can even establish compensation elements for advertising agencies (Swain, 2004). In addition, measuring advertising effectiveness requires methods that ensure IMC programmes are able to focus on profitable customers and the media that will influence them. Therefore, the IMC results are assessed by considering the expected consumer responses, the expected results and the measurement methods used.

Consumer insight in planning advertising campaigns is important in order to attract consumers (Sánchez-Blanco, 2010) because it can guide designers in adapting advertising communication elements and linking the types of response expected. Marketing professionals must therefore research consumer behaviour by analysing their responses and improving the definition of communication objectives (Seric and Gil-Saura, 2012).

Measuring the results of marketing communication programmes against established targets has always been standard practice for business organisations. Given that IMCs are a process, its components can be considered as antecedents and consequences (Kliatchko, 2008; Tafesse and Kitchen, 2017). The antecedent elements are integrated into the planning and execution of new IMC programmes (because these programmes include a measurement, evaluation and analysis feedback mechanism that will impact future approaches). Accordingly, the improvements, changes and other adjustments made in response to the findings of the analysis, subsequently act as consequences.

Although IMC has a proven capability to provide positive returns, create value, foster relationships with stakeholders and generate competitive advantages (Jiménez, 2006), it is also clear that communication budget managers are under pressure. to quantify the impact of these activities (Rust et al., 2004). Therefore, based on the expected results, managers plan advertising campaigns and allocate the required resources and capabilities. Although from the theoretical point of view, the first step is planning, changes can occur in practice, which is also supported by the lack of generalised conceptual clarity regarding management of IMC (Porcu et al., 2017).

Therefore, IMC's results constitute the inputs for advertising campaigns planning exercises. In accordance with the above, the following hypothesis are proposed:

H1: The types of expected consumer responses influence the planning of advertising campaigns.

H2: The expected results in advertising management influence the planning of advertising campaigns.

H3: The measurement methods used to evaluate the impact of advertising management influence the planning of advertising campaigns.

Academics and organisations sought to quantify the degree to which advertising influences consumer behaviour and what reactions it provokes at cognitive, emotional, attitudinal and behavioural levels (Eisend and Tarrahi, 2016). In order to assess these reactions, effective measuring methods must be applied according to the expected type of consumer response. An advertising campaign may have different objectives and consequently, different types of expected responses (Beerli and Martín-Santana, 1999). For example, researchers mostly assess campaigns based on memory or advertising recalling (cognitive response), attitude towards the brand and ad (affective response), and purchasing intention (conative response) (Kim and Han, 2014).

Gabriel et al. (2006) demonstrate how advertising agencies use methods to measure advertising effectiveness that are related to the hierarchy of effects, albeit with some variations. Even though some advertising agencies resist understanding their output in this way, it is useful to classify these measurement methods according to the advertising campaign's objectives. According to Ferrer (2006), advertising organisations and agencies assess advertising effectiveness based on the campaign's objectives and therefore, the types of response they expect from the target audience. These are usually evaluated based upon variations in sales levels and secondly, brand recall and awareness. In accordance with the above, the following hypothesis are proposed:

H4: The types of responses expected from the consumer influence the measurement methods used to assess advertising management.

H5: The expected results of advertising management influence the measurement methods used to assess advertising management.

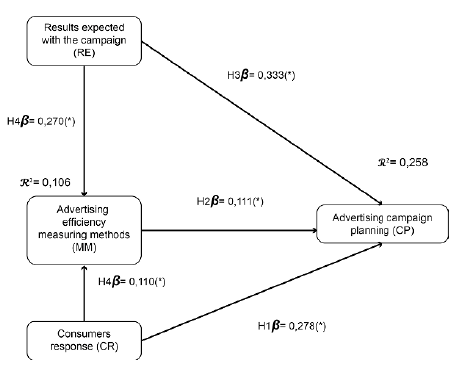

According to the hypothesis proposed, Figure 1 shows the conceptual model that will be validated (See Figure 1)

3. Methodology

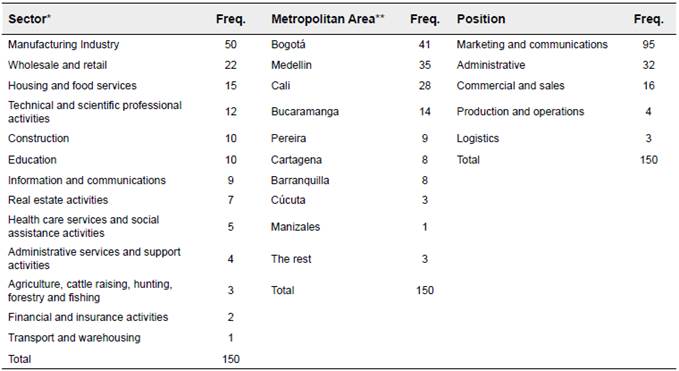

To test these hypothesis, the cross-section survey methodology was used. The units of analysis of this study are medium and large companies located in Colombia because these types of companies are especially prominent in terms of their investment in advertising (Pérez, 2016) and levels of sales department (Superintendencia de sociedades, 2015). Marketing managers directly involved in investment decisions in marketing, specifically in the allocation of resources for advertising investment, were contacted. Surveyed organisations had implemented at least one advertising campaign in the last 6 months. In total, 162 surveys were completed, but I2 surveys were discarded because they presented inconsistencies in the answers (such as marking the same score for each question).

The fieldwork was carried out between August and October 2016. The sample was distributed as indicated in Table 2. According to the Departamento Administrativo de Estadísticas (2017), the large companies comprise 9% of the overall business market, and medium companies comprise 22%. This means that the sample in this study had a large company participation rate close to 30% (31.33%). Economic sectors and metropolitan areas were not determining variables in the study but they demonstrate its scope.

A questionnaire was initially designed using the scales from previous studies (see Appendix 1) and evaluated by seven marketing and advertising experts; its goal was to assess each statement based on its relevance and wording, to determine if they adequately represent the construct. The evaluation of the experts used the following scale: I =eliminate the answer, 2 = modify it and 3 = maintain it. The validity coefficient was calculated to measure the degree of agreement among experts; the result of the evaluation was to eliminate 6, modify 21 and maintain I2 of the observable indicators. The final version of the questionnaire was implemented by telephone to marketing managers because they have a stronger role in the decision-making processes regarding advertising investment. However, some surveys were directed to administrative positions in charge of this type of decisions.

Regression analysis of the latent variables used in this study was carried out using the Smart-plus 3.0 PLS program, based on the partial least-squares optimisation technique (PLS), a multivariate analysis recommended for testing exploratory models (Escobar-Rodríguez and Carvajal-Trujillo, 2014; Kiwanuka, 2015; Matute Vallejo, Polo Redondo and Utrillas Acerete, 2015). The data analysis was conducted in two stages. In the first stage, the measurement model was assessed, and the second stage assessed whether the structural model predicts the proposed relationships.

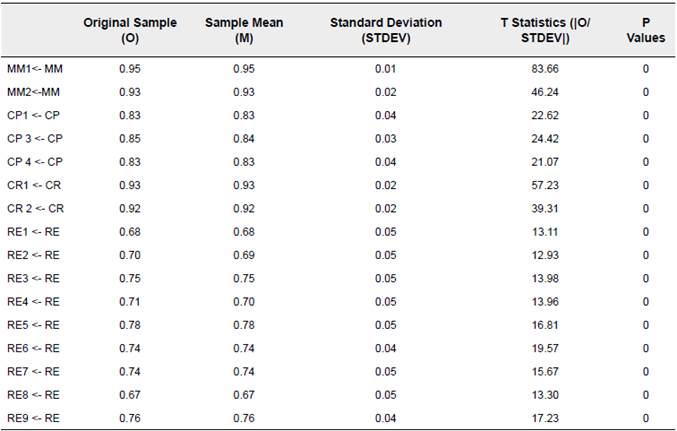

3.1 Validation of the measurement model

To validate the measurement model, an exploratory analysis was carried out. The first step established the constructs' convergent and discriminant validity, i.e. each item's measurement reliability. The convergent validity of each construct was acceptable because all loads exceeded 0.505 (Hair, Hult, Ringle and Sarstedt, 2014). Similarly, each item's individual reliability was measured by the correlations of each item's loads when compared to each variable. Table 3 verifies that the loads for each indicator were significant, all of which were validated.

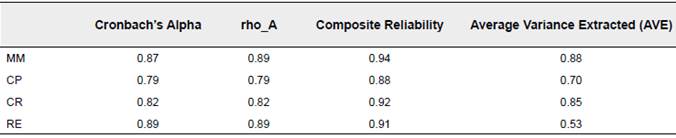

In order to measure each indicator's internal measurement consistency in relation to their corresponding variables, the Dillon-Goldstein's test (known as the composite reliability coefficient) was applied. The test results indicated that all values exceeded the acceptable minimum of 0.70 (Gefen, Straub and Boudreau, 2000). Cronbach's alpha test was also applied; for both sample groups, this yielded values above 0.7, the minimum value allowed for confirmatory studies (Churchill and Lacobucci, 2018). Finally, the convergent validity was analysed again, this time taking the variance into account; that is, incorporating the finding of similar variance between the indicators and their construct. Here, the AVE must be greater than 0.50 of the variability explained by the indicators (Fornell and Larcker, 1981) being greater in the two groups (see Table 4).

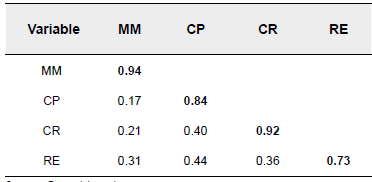

Discriminant validity was checked by comparing each variable's AVE value to each construct's correlation to each squared variable, considering that the values obtained from the AVEs' square root are higher than those of the constructs. Therefore, it can be considered that each variable is related with greater intensity to its own items than to those of the other variables.

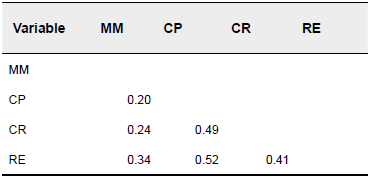

Table 5 shows that the variance shared between each pair of constructs (squared correlation) was lower than their corresponding extracted variance indexes (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Likewise, Table 6 shows the results of the Henseler-Ringle test, where the values are below 0.90. This is also considered acceptable to confirm divergent validity (Hair, Henseler, et al.. 2014).

4. Results

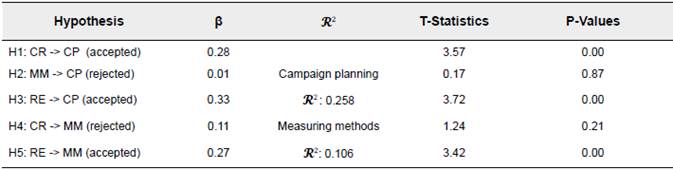

First, the model was found to fulfil its predictive capacity because all R2 values are greater than 0.1 (Hair, Hult, et al., 2014). The validity of the dependent variables' effects over the independent variables was checked via resampling. Bootstrapping was performed with 5,000 subsamples taken at random to act as a contrast for the significance of the model's parameters (Hair, Hult, et al., 2014). However, the low value of R2 means that the model is not able to predict outcomes. Therefore, more explanatory variables should be added in future studies.

Table 7 presents statistics that the relations between constructs. The partial least-squares optimisation model's results reject Hypothesis H2 = β: 0.011 (p-value = 0.869). Therefore, effect of methods used to measure an advertising campaign's effectiveness do not have a significant impact on the planning of future campaigns. Hypothesis H4 = β: 0.110 (p-value = 0.214) is also rejected, indicating that the effect of the consumer's expected responses on the methods used to measure advertising effectiveness is not significant. However, Hypothesis HI = β: 0.278 (p-value = 0.00) is accepted, indicating that consumer's expected responses have a significant impact on the planning of advertising campaigns. Hypothesis H3 = β: 0.333 (p-value = 0.00) is also been accepted, thus upholding that the expected results do have a significant influence on the planning of advertising campaigns. In addition, Hypothesis H5 = β: 0.270 (p-value = 0.01) is also upheld, validating the relevance of the expected results' effect on methods used to measure advertising effectiveness. In addition, although relations are found to exist between non-relevant constructs, all relations are positive. Figure 2 summarises the conceptual model's results and hypothesis proposed.

5. Discussion

According to the proposed model's results (see figure 2), there is no empirical basis for claiming a significant relation between the methods used by organisations to measure advertising effectiveness and how those organisations plan future campaigns. Similarly, no relation was found to exist between a campaign's results and the methods used to measure those results. The inverse relationship of these variables was also analysed, but no significant relation was found (β: 0.028 p-value = 0.72). Therefore, it can be shown that organisations are not linking these variables because they place more priority on directly assessing the impact of campaigns in terms of achieving the expected results; they give little attention to assessing the intermediate components that could improve management of the advertising process.

On the other hand, organisations consider it important to plan advertising campaigns based on the responses they expect from consumers and the market. The previous analysed results fail to establish whether the methods used to measure advertising effectiveness are related to advertising management.

Previous studies support that organisations use the expected results and types of consumer responses to support campaign planning (Nyilasy and Reid, 2009). These are inputs to a feedback process derived from experience implementing past campaigns as aligned with organisational objectives. It has also been confirmed, in an exploratory manner, that organisations assume that the results expected from a campaign should determine (to a certain extent) the methods used to measure the effectiveness of brand communication (Ferrer, 2006)

These findings also indicate that methods used to measure advertising effectiveness are less influential within the management process analysed in this study. This has also been shown in previous studies, which suggest this issue acts as a barrier to measuring and evaluating advertising campaigns (Ebren, Kitchen, Aksoy and Kaynak, 2005). In general, advertising expects medium- and long-term results and additional investments are needed to collect the data that allow for these results to be calculated (Petersen et al., 2009). This is one reason why organisations are more focused on measuring advertising effectiveness in terms of sales, i.e., because this information already exists and can simply be subtracted from financial statements; it does not require another type of investment or measuring method. This result contradicts the advertising theory basis, which outlines in detail the measurement methods that organisations must conceive to reliably evaluate the effectiveness of advertising (Beerli and Martín-Santana, 1999).

According to the above findings, the persistence of the gap between theory and advertising practice fostered by the short-term focus on process management is evident because practitioners give little value to marketing management and to the results of academic research (AMA Task Force, 1988; November, 2004; Southgate, 2006).

For this reason, it is necessary to regard organisations as a unit of analysis and link them to academic research on advertising management because the responsibility for measuring advertising effectiveness cannot rest solely with advertising agencies (Porcu Del Barrio-García, Kitchen, 2017). It cannot be overlooked that organisations are responsible for marketing budgets and that they expect to use those budgets to make an impact in the market, which in turn will generate organisational value. In addition, they behave as an agent who integrates the creative team, the media, and the measurement of results. Comparing advertising management in organisations with the processes used in advertising agencies will help align efforts and determine each party's objectives in interpreting the scope advertising beyond the creative component of announcements (Behboudi et al., 2012).

6. Conclusions

Research on advertising management in organisations is scarce. For this reason, this study offers a relevant contribution in this field by exploring the relations among factors surrounding advertising management in Colombian organisations, with a focus on factors that are supported by IMC theory. This study is empirical and exploratory, and it expands existing knowledge, with academic and organisational implications. From an academic point of view, organisation's reluctance to apply measurement methods to the advertising processes, an action that would require investment of marketing research resources by the organisations, can be extended to the scope of IMC. This lack of evaluation detracts from the MIC's usefulness and serves as a reason why the lack of consensus regarding its theoretical delimitation has become widespread (Porcu et al,, 2017).

From an organisational point of view, there are weaknesses in implementing measurement methods that could properly calculate organisational results concerning advertising investment. Hence, it is important that organisations incorporate metrics into advertising management to measure the expected results in the target audience and market, according to the organisation's capacity and beyond only sales goals. As a consequence, organisations must take the risk of proposing measuring methods that, despite of involving additional investments, provide reliable information and thus, facilitate future decision-making. This approach will positively demonstrate the value of marketing because it provides rigorous marketing processes by including not only financial metrics but also attitudinal and behavioural metrics (Hanssens and Pauwels, 2016).

If organisations measure the level of compliance with the goals established in terms of IMC, they will make better decisions and allocate marketing budgets consistent with their objectives, resources, capabilities; the improvement of their advertising management systems will positively impact the reduction of uncertainty levels by better measuring the return on advertising investment. From an academic perspective, it is necessary to continue exploring organisational barriers to using measurement methods in their processes.

This is especially relevant in advertising management for the purpose of testing the impact that CIM has on the generation of organisational value. Future research may also establish control variables such as the life cycle of brands and organisations, the size of organisations or the type of marketing strategy implemented (among others) to assess whether these are determining aspects in managing advertising (Reid, 2005). Furthermore, including in the IMC the perspective of roles other than marketing managers that also influence the decision-making process can be useful to extend the theory.