Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Entramado

Print version ISSN 1900-3803On-line version ISSN 2539-0279

Entramado vol.19 no.1 Cali Jan./June 2023 Epub Apr 05, 2023

https://doi.org/10.18041/1900-3803/entramado.1.8644

Science and y Technology

Peasant Occupation and Use of the Land in the Municipality of Pradera (1900-2010): A century of socio-territorial tensions*

1 Investigador Instituto de Estudios Interculturales de la Pontificia Universidad Javeriana de Cali, Cali - Colombia hordonezb@gmail.com

Although the current guidelines for the Social Planning of Rural Property (OSPR, acronym in Spanish) establish, among other criteria, the mainstreaming of a differential perspective and the inclusion of ethnic communities, land-rights for peasants are not expressly recognized. Drawing from the theoretical perspectives of Agrarian Structuralism and the Socio-Territorial Approach, this paper proposes complementary guidelines to support an OSPR process that recognizes this right, in the districts that are currently being projected for the constitution of a Peasant Reserve Zone (ZRC, acronym in Spanish) in Pradera, Valle del Cauca. To this end, we describe the historical dynamics of the settlement and appropriation of the land by the peasantry and, within the ZRC polygon, we geospatiolize the properties by range of size, soil coverage and fertility and the zoning of the Forest Reserve, through which we provide evidence for the existence of a peasant territoriality, the need to redistribute land, to subtract areas of the Forest Reserve and to accelerate the constitution of the ZRC.

KEYWORDS: Social planning of rural property; peasant reserve zone; land distribution; socio-spatial analysis; disputed territorialities

Si bien los lineamientos vigentes para el Ordenamiento Social de la Propiedad Rural-OSPR establecen, entre otros criterios, la transversalización del enfoque diferencial y la verificación de presencia de comunidades étnicas, no se reconoce expresamente el derecho a la tierra del campesinado. Partiendo de las perspectivas teóricas del Estructuralismo Agrario y del Enfoque Socio-Territorial, este trabajo busca proponer lineamientos complementarios para adelantar un proceso de Ordenamiento Social de la Propiedad Rural OSPR que reconozca este derecho, en los corregimientos que actualmente están siendo propuestos para la constitución de una Zona de Reserva Campesina (ZRC) en Pradera, Valle del Cauca. Para tal fin, se hace un acercamiento a la dinámica histórica del poblamiento y apropiación de la tierra por parte del campesinado y se geoespacializan dentro del polígono de la ZRC los predios por rango de tamaño, las coberturas y fertilidad del suelo y la zonificación de la Reserva Forestal, con los cuales se evidencia la existencia de una territorialidad campesina, la necesidad de redistribuir la tierra, de sustraer áreas de la reserva forestal y de acelerar la constitución de la Zona de Reserva Campesina (ZRC).

PALABRAS CLAVE: Ordenamiento social de la propiedad rural; Zona de Reserva Campesina; distribución de la tierra; análisis socio-espacial; territorialidades en disputa

Embora as diretrizes atuais para a Ordenação Social da Propriedade Rural-OSPR estabeleçam, entre outros critérios, a integração da abordagem diferencial e a verificação da presença de comunidades étnicas, o direito à terra do campesinato não é expressamente reconhecido. Baseado nas perspectivas teóricas do Estruturalismo Agrário e da Abordagem Sócio-Territorial, este documento procura propor diretrizes complementares para avançar um processo de OSPR que reconheça este direito nos municípios que estão sendo propostos atualmente para a constituição de uma Zona de Reserva Camponesa (ZRC) em Pradera, Valle del Cauca. Para este fim, é feita uma abordagem da dinâmica histórica do assentamento e apropriação da terra pelo campesinato e a geo-espatização dentro do polígono da ZRC das propriedades por faixa de tamanho, cobertura e fertilidade do solo e o zoneamento da Reserva Florestal, que mostra a existência de uma territorialidade camponesa, a necessidade de redistribuir a terra, de subtrair áreas da reserva florestal e de acelerar a constituição da ZRC.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Regulamentação social da propriedade rural; Zona de Reserva Camponesa; distribuição de terras; análise sócio-espacial; territorialidades disputadas

1. Introduction

Political violence, at the beginning of the twentieth century, was the engine of the displacement of the settlers who founded the peasant territories in Pradera. By the end of the century and starting the twenty-first century, it also caused the displacement and dispossession of the lands of their descendants. This new cycle of violence led to the concentration of land, the uneconomic fractionation of property and informality in tenure, but this time in a context of greater complexity, given the creation of the Forest Reserve Zone-ZRF, the constitution of the Kwet Wala Kiwe Indigenous Reservation and the overflowing expansion of sugarcane monoculture since the 60s.

In response, peasant organizations have been promoting the constitution of a ZRC that allows, among other things, access to and redistribution of land ownership. This figure of social, productive and environmental ordering, based on article 64 of the Political Constitution of 1991 and created by Law 160 of 1994, was defined as a geographically delimited area, characterized by the predominance of vacant land, where processes of peasant colonization have historically taken place, associated with strong organizational dynamics and the presence of favorable conditions for the peasant economy (Fajardo, 2014). In turn, the purpose of the ZRC is to guarantee decent living conditions so that the peasantry, as the holder of acquired rights that cannot be violated or ignored (Corte Constitucional, 2014), can remain in the territory transmitting their knowledge, background and culture from generation to generation.

Taking into account that land concentration has been raised as a structural element of the agrarian problem in Colombia (PNUD, 2011; ILSA, 2014; DNP, 2015; Guereña, 2017), this research is based on three basic concepts: a) land concentration, b) land distribution, and c) social ordering of rural property-OSPR (acronym in Spanish). These will be described briefly below.

In the first place, according to Fajardo (2015), land concentration is understood as the process through which powerful groups in Colombia have appropriated land, through mechanisms ranging from the formulation and implementation of policies for the appropriation and distribution of public lands favorable to their interests, to the systematic exercise of violence to separate rural communities from their lands and territories, limiting their access.

For its part, the distribution of land ownership is understood as "(...) the way in which the relationship of owners with rural properties is configured" (UPRA, 2015, p. 3), and can be distributed in a unimodal, bimodal or multimodal way. According Suescún (2013), the backwardness and underdevelopment of the rural sector in Colombia is due to a bimodal agrarian structure

(...) which, although it is mainly based on the polarization of land tenure, is also characterized by low taxation in the rural sector high conflict between small and large landowners and low levels of savings, investment and growth... (p. 660).

Thirdly, the OSPR was defined by the UPRA (2017) as:

(...) a planning and management process to order the occupation and use of rural lands and to administer the Nation's land, which promotes progressive access to property and other forms of tenure, equitable land distribution, legal security of land tenure, planning, management and financing of rural land, and a transparent and monitored land market, in compliance with the social and ecological function of property, in order to contribute to improving the quality of life of the rural population (p. 4).

However, from a socio-territorial perspective, the OSPR has been criticized. For example, (Mançano, 2006) describes the territory as the physical and social space that is controlled, appropriated and dominated by some social actors. This conception allows us to understand that the exercise of power over space by different social actors, dynamizes processes of territorial planning and creates various territorialities, which - when juxtaposed - are braided in socio-territorial conflicts.

In this sense, two aspects of the Colombian political constitution reflect these correlations of forces and are expressed in territorial planning. On the one hand, there is private property, since its conception before the constitution of 1991 referred to an absolute right of free use, enjoyment and disposal of the good; while, with the inclusion of the social and ecological function of it, "(...) radically changed the traditional form of rural land use and management and (opened up) a solidarity-based way of inhabiting the territories" (Estrada, 2013, p. 203). On the other hand, the asymmetrical recognition of territorial rights for rural communities from this constitution has resulted in greater inequalities between indigenous, Afro-descendants and peasants (Duarte and Castaño, 2020), expressing themselves in conflicts over the constitution of reservations, collective titles and/or ZRC.

In this regard, the question arises: How to order the territory to guarantee access and redistribution of land by the peasant communities of Pradera, as a necessary condition for permanence in the territory in dignified conditions?

So, this work seeks to propose complementary guidelines to advance an OSPR that benefits the peasantry in the municipality of Pradera-Valle del Cauca, specifically in those areas that are currently proposed for the constitution of a ZRC. Assuming that this figure serves as a mechanism to correct the processes of concentration and uneconomic fractionation of property -decrease in size below the economic viability of agricultural activities-, facilitating a comprehensive execution of rural development policies. It should be understood that rural development is a model associated with the equitable redistribution of land, the strengthening of the peasant economy and environmental conservation practices; in other words, rural development lies in the improvement of the living conditions for rural communities.

To this end, after this introduction, a section will be dedicated to addressing the process of occupation of the lands in Pradera, pointing out relevant milestones to understand the emergence of the peasantry and the different situations that have led to the current land tenure and distribution. Next, the distribution of land property in the area is dimensioned and mapped by size ranges, an approximation is made to the situation of formality in land tenure and some biophysical characteristics are geo-spatially specified to counterbalance the socio-territorial tensions. Then, the discussions between the collected data and the theoretical framework of reference are presented. The conclusions outline the proposals of complementary guidelines for the OSPR in the ZRC of Pradera in the process of constitution.

2. Methodology

This research has been carried out in the context of a social commitment to the popular causes of the peasantry of the municipality of Pradera, located in the south-eastern region of the department of Valle del Cauca, adopting a methodological design that relates community knowledge regarding the construction of its own territory to information and theoretical approaches related to OSPR and ZRCs.

To achieve the objectives, primary and secondary sources were consulted, seeking quantitative and qualitative information. The consultation of secondary sources revolved around the critical analysis of the regulations on the OSPR and the ZRC in Colombia. I also reviewed Colombian case studies published in the last decade related to land distribution.

In addition, using frequency distribution as a descriptive statistical analysis technique (Hernández-Sampieri, Fernández-Collado y Baptista-Lucio, 2014), I made an approach to the demographic dynamics, the type of land tenure, the type of productive activities and the range of property sizes in the delimited study area, from the databases of the National Census Agricultural-CNA, DANE, IGAC and ANT. Besides, a spatial analysis was made (Rodríguez y Rincón, 2018) with Geographic Information Systems, from the polygon delimited by the team of the Instituto de Estudios Interculturales-IEI, using the open databases of the CVC, the IGAC and the cartography associated with resolution 1922 of 2013 of the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development - (MADS, acronym in Spanish), as a mixed method to make the property and biophysical characterization of the study area.

Through qualitative methods and work with the community as a primary source, within the framework of the fieldwork carried out by the IEI (Convenio No. 943 de 2019 ANT-UNDP-IEI), 5 semi-structured interviews were conducted (Hernández-Sampieri et al. 2014, p. 403) between the months of August and November 2020 (four individual and one collective) to 7 leaders of the rural towns of San Isidro, Lomitas, La Feria, La Fría and La Ruiza; selected because of their family affiliation with founders and leaders of the rural towns, as well as for their active role in social and community dynamics, developing a dialogue around three thematic axes: the history of settlement in the region, the history of conflicts in the territory and projections on the issue of land distribution. Finally, the results of the interviews were systematized, classified and organized using Microsoft Excel software to identify the most relevant elements around the axes of dialogue.

It is necessary to clarify that the health crisis generated by the COVID-19 pandemic since the beginning of 2020, negatively impacted the methodological development of research, both due to the limitations to travel to the territories, and due to the impossibility of accessing secondary sources that can only be found in the Mario Carvajal Library of the Universidad del Valle. However, every effort was made to maintain the rigor of the investigative process.

3. Characterization of the Problem of Peasant Land in Pradera

3.1. Process of colonization and formation of a peasant territory (1900-1960).

The repopulation (Palacio, 2006) of the temperate and cold lands of the municipality of Pradera starts in the early twentieth century, initially in the rural towns of Lomitas and El Retiro in the year 1,900, with the arrival of settlers from Cauca, Cundinamarca and Viejo Caldas. These dynamics will continue for the following decades with the arrival of more settlers (mestizos and indigenous) from Cauca, Tolima, Boyacá and the flat area ofValle del Cauca, until the 60s when the village of San Antonio was founded (ANZORC; CMDR, 2019, p.12).

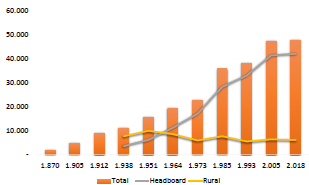

This process had a significant impact on the population growth of the municipality during the aforementioned period, as can be seen in Figure 1. The tendency to grow the rural population until 1951 is clear, representing the majority of the population of the municipality until 1964, when the effects of "La Violencia" become evident and the agro-industry of sugar cane begins to flourish, increasing the population in the urban area to almost sevenfold that of the rural area (DNP, 2021) which decreased by 38.5% between 1951 and 2018.

Source: Elaborated by the author based on: (Valdivia, 1980, p. 108), (DANE, 1905), (DANE, 1912), (DANE, 1942), (DANE, 1951) , (DANE, 1964), (DANE, 1973), (DANE, 1985), (DANE, 1993), (DNP 2021)).

Figure 1 Comparison of Pradera Population growth in urban vs. rural area (1870-2018).

Without state presence, without access roads or advanced means of communication, the appropriation of land for the opening of their farms was done through de facto possession, using as a mechanism of delimitation, geographical accidents "the scope of their view" and respect for the value of the word, constituting medium and large farms. A relevant aspect in this regard, pointed out by all the people interviewed, is the criterion of family kinship or some kind of social bond, between the founding settlers and the peasant families to whom they subsequently ceded or sold part of their land. This ultimately configured communities (the current rural towns with very close kinship ties, as well as codes of conduct contained in norms of community coexistence that guaranteed for some time their harmony and internal stability. In this regard, one of the founders of the San Isidro points out:

Drug traffickers didn't buy land here, but I know that they did in other places, such as La Carbonera, Los Pinos and in the flatlands. Here there was an agreement in the community that we wouldn't sell to just anyone and that helped us a lot. Now that has been forgotten and they don't even tell the JAC that they are going to sell, let alone to whom (interview 4, 21 October 2020).

This process also involved the arrival of new crops, produced with different cultural practices that gradually characterized the region as a food pantry for municipalities such as Palmira and Cali. Food that was transported to the markets on the back of a mule through bridle paths open to pick and shovel in days of community work, as the leader of San Isidro remembers:

At that time, to go down to the village, it was on foot or on horseback. My father had some beasts and with them, he transported the mafafa, granadilla, yucca, arracacha and coffee; that was what he took to sell to Pradera and sometimes to Palmira. And there were many people who went from here to Cali. The road here arrived in 65 or so. First we started it with picks and shovels from down there in Pueblo de Lata... (interview 4, October 21, 2020).

In this way, a new territory was woven in the temperate and cold lands of the Andean Mountain range of southeastern Valle del Cauca: the territory of the mountaineering peasantry. Likewise, a new social group was created in the municipality, from the appropriation of the land and transformation of the landscape for food production in agro-diverse family farms, adapting themselves to new conditions and intercultural population. The rigors of the internal armed conflict would affect this particular social group, as will be seen below.

3.2. War and the configuration of the bimodal structure (1960-2010).

With the consolidation of peasant territories in Pradera, new conflicts will arise between these and other actors that affect the territory. In addition to the conflict over land, the leaders interviewed pointed to the conflict over water with the sugar mills as the main socio-territorial conflict, followed by the conflict over the burning of sugar cane and the conflict over the fumigation of sugarcane fields, which have negative consequences for the environment, crops and the health of peasant families. Also, the problem of military actions was pointed out as the main socio-territorial conflict with the State.

However, the conflictive nature of the process of repopulation of the territory went through a period of degradation during the last four decades of the twentieth century and the first of the twenty-first, when the vicious cycle of violence reached the paroxysm of the narco-paramilitary reaction. A phenomenon that, according to the CNMH (2014) was sponsored by drug traffickers and some sectors of Valle del Cauca business with the connivance of the State, in the face of growing social resistance against the injustices of the socio-economic and political model promoted by the elites. This was expressed in multiple ways, such as the emergence of peasant associations, the organization of sugarcane cutters' unions, the creation of indigenous councils and the arrival of insurgent organizations such as the M-19 and the FARC-EP.

According to the reconstruction of the historical memory of the social and armed conflict in the municipality (Corporación para el Desarrollo Regional, 2018), between the decades of 1960-1970 there was an intense process of land concentration, sponsored by landowners who pressured peasants in different ways for the sale of their farms, as well as a process of productive transformation, from being "(...) part of the "agricultural larder of Colombia", where cotton, bananas, beans, millet and fruit trees were grown, to a territory with land dedicated to the monoculture of sugar cane." (p. 43).

Subsequently, between 1998 and 2001, the armed conflict would degrade until it reaches the vortex of paramilitary massacres that occurred in towns such as La Ruiza, combined with multiple atrocities committed throughout the territory under the pretext of fighting the FARC EP guerrilla, with the peasantry being one of the main affected with 41.3% of the total registered victimizing events (IEI Universidad Javeriana de Cali. Dejusticia y Comisión Colombiana de Juristas., sf).The most significant consequences of this whole process were the massive displacement of rural communities, dispossession and increased land concentration, reflected in the registration of 5,306 people forcibly displaced by 2015. (Observatorio para la paz del Valle del Cauca, 2015, p. 27). Pradera was thus categorized as municipality with a high Victimization Risk Index- IRV. Likewise, the UPRA (2016) found that Pradera has a Gini index of rural property of 0.8863, which means that the 10% of the owners concentrate about 84% of the area of the private agricultural properties of the municipality.

However, there is a contrast in the response of communities to these phenomena. On the one hand, the inhabitants of the flat zone were subsumed by the development of the sugarcane agroindustry, being proletarianized and displaced to the urban area of the municipality, in a process that is combined with the dynamics of land concentration and the "demographic draining" process (García, 1986, p.56). On the other hand, the mountaineering peasants have sustained the permanence of their culture and economy in the territory until the present, despite the war and at the expense of the uneconomic fractionation of their farms and the pauperization of their economies, as will be seen in the next section.

3.3. Land tenure in the ZRC-Pradera formalization or redistribution?

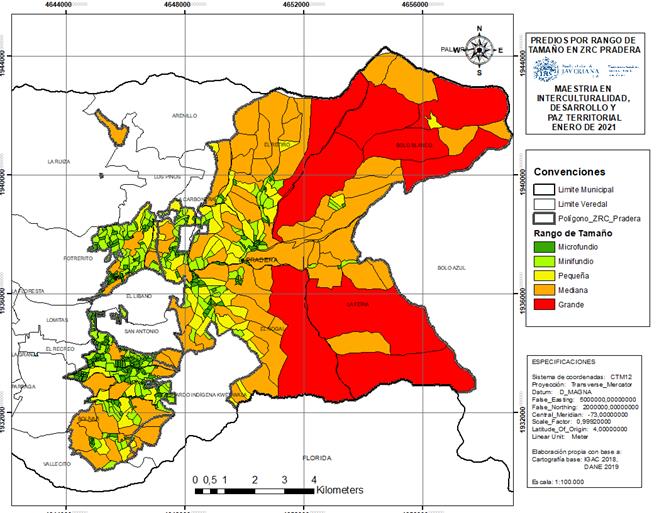

According to the cadastral information, the municipality of Pradera has a total of 3,393 rural properties that occupy 35,678.06 ha (IGAC, 2018), of which 748 properties are within the polygon proposed for the constitution of a ZRC. That is, 22.04% of rural properties, distributed in 13 rural towns with a total area of 9,633.5 ha (Figure 2).

Source: Elaborated by the author based on the IGAC (2018), DANE (2019)

Figure 2 Properties by size range in the Pradera ZRC in the process of constitution.

Regarding the number of properties by size range in each of the rural towns of the ZRC, it was found that in 11 rural towns, microfundios (less than 3 ha) predominate, with the exception of La Feria where smallholdings and medium property predominate, and Bolo Blanco where medium and large property predominate (see Table 1). Similarly, it was found that the microfundios occupy 386 ha, the smallholdings 779.4 ha, the large property 3,815 ha and the median property occupies 3,888.5 ha.

Table 1 Number of Properties by size range by districts of the ZRC-Pradera.

| Rural town | Area | Properties <3 ha (Microfundio) | Properties 3-10 ha (Smallholding) | Properties 10-20 ha (Small property) | Properties 20-200 ha (Median property) | Properties >200 ha (Large property) | Total Properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bolívar | 627.7 | 30 | 14 | 4 | 9 | 0 | 57 |

| Bolo Blanco | 2,516.4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 10 | 5 | 24 |

| Carbonera | 382.7 | 31 | 16 | 7 | 5 | 59 | |

| El Nogal | 1,687.2 | 44 | 15 | 14 | 13 | 1 | 87 |

| El Recreo | 10.1 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| El Retiro | 1,273.8 | 31 | 12 | 9 | 13 | 1 | 66 |

| La Feria | 2,243.4 | 11 | 18 | 9 | 14 | 2 | 54 |

| La Fria | 270.7 | 74 | 17 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 97 |

| La Ruiza | 46.7 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Lomitas | 19.5 | 16 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 |

| Potrerito | 329.5 | 130 | 30 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 164 |

| San Antonio | 17.3 | 20 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21 |

| San Isidro | 208.5 | 72 | 12 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 87 |

| Total | 9,633.5 | 475 | 141 | 51 | 72 | 9 | 748 |

| 63.50 | 18.85 | 6.82 | 9.63 | 1.20 | 100 |

Source: Elaboration by the author based on the information of the IGAC (2018).

Taking into account that, in mentioned area, the Family Agricultural Units-UAF are in the range of 9 to 13 ha for farms between 1,000 and 2,000 meters above sea level and, between 17 and 23 ha for farms between 2,000 and 2,500 meters above sea level, (INCORA, 1996) there is a characteristic situation of bimodal agrarian structure, given by the minifundization of most properties together with the concentration of land in large properties. In addition, the information of the CNA 2014 indicates that 1,910 people live in the ZRC and there are 911 Productive Units (UP), of which 880 are agricultural (UPA) and 31 non-agricultural (UPNA) (DANE, 2015). It should be noted that 96.6% of the UP surveyed in the area have an agricultural character and represent 53.3% of the municipal total (Table 2). In addition, about 60% of the rural population lives there, which indicates the persistence of the peasantry in its territory and confirms that smallholdings are the natural counterpart in the bimodal agrarian structure (García, 1986, p. 59).

Table 2 Number of UPA-UPNA and people by town in Pradera

| Town | Up | Upa | Upna | People |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arenillo | 10 | 10 | 0 | 58 |

| Bolívar | 47 | 47 | 0 | 55 |

| Bolo azul | 18 | 18 | 0 | 12 |

| Bolo blanco | 13 | 13 | 0 | 21 |

| Bolo hartonal | 192 | 172 | 20 | 250 |

| El libano | 63 | 62 | 1 | 129 |

| El nogal | 151 | 151 | 0 | 263 |

| El recreo | 23 | 23 | 0 | 75 |

| El retiro | 89 | 87 | 2 | 165 |

| La carbonera | 39 | 38 | 1 | 93 |

| La feria | 66 | 66 | 0 | 94 |

| La floresta | 166 | 153 | 13 | 228 |

| La fría | 46 | 46 | 0 | 92 |

| La granja | 36 | 36 | 0 | 28 |

| La ruiza | 33 | 31 | 2 | 67 |

| La tupia | 136 | 117 | 19 | 359 |

| Lomitas | 171 | 153 | 18 | 486 |

| Los pinos | 76 | 72 | 4 | 86 |

| Parraga | 13 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| Potrerito | 105 | 99 | 6 | 218 |

| Resguardo indígena Kwet Waia | 22 | 22 | 0 | 41 |

| San Antonio | 75 | 73 | 2 | 158 |

| San Isidro | 53 | 53 | 0 | 123 |

| Talaga | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Vallecito | 66 | 66 | 0 | 75 |

| 33 | 28 | 5 | 17 | |

| Total | 1744 | 1651 | 93 | 3193 |

Source: Elaborated by the author based on the information of the CNA 2014 (DANE, 2015).

In terms of the type of land tenure, of 885 UP registered, 585 are owned (61.51%), 100 leased (10.5 2%), 72 are not known (7.57%), 45 have other forms of tenure (4.73%), 32 are successful bidders (3.36%), 27 are mixed (2.84%), and the rest of the forms are distributed in percentages below 1% (DANE, 2015). Despite these data, three collective occupation processes were identified in the interviews: one in Bolo Blanco, with 30 families and 30 pieces of ground; one in San Isidro with 15 families and 15 pieces of ground; and one in La Feria with 25 families and 25 pieces of ground. All processes are more than 15 years old and two are within the ZRF of law 2 of 1959.

Assuming that there is formalization of land ownership when the rights of use, control and transfer of land are fully accessed (FAO, 2003, p. 12), it has to be that the rural town with the highest percentage of formality is La Fría with 86.96% of the UP surveyed. On the other hand, the highest percentage of informality is in La Feria with 50% of the UP. Thus, it can be affirmed that, in the area of study, more than formalization processes, a profound process of access and distribution of land is required.

3.4. Land uses in the ZRC-Pradera: pauperization of the peasant economy.

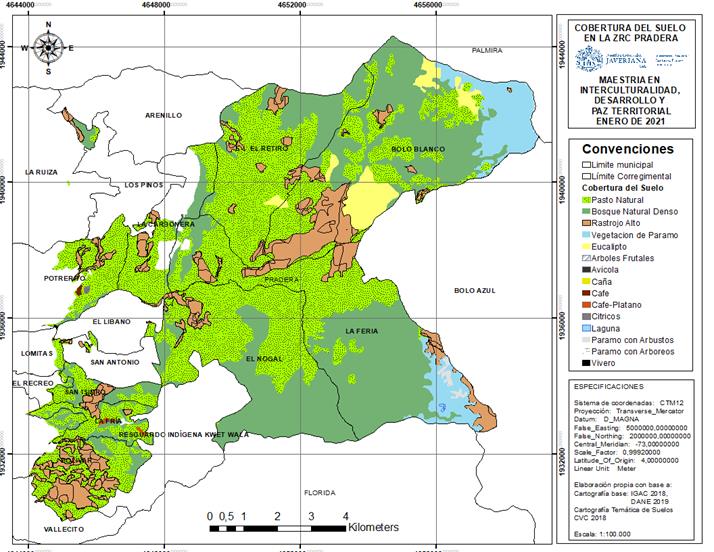

In addition to the characterization of land tenure in the ZRC, geospatial analysis of some of its biophysical conditions was carried out, using information from the 2018 General Soil Study carried out by the CVC at a scale of 1:100,000 (2019), to discuss the problem of land use. Thus, it was found that the main covers are the Natural Pasture (PCU) and the High Dense Natural Forest (BNDALT), which together represent 79.64% of the area distributed throughout the polygon, as shown in Figure 3 and Table 3.

Source: Elaborated by the author based on the information of the IGAC (2018), DANE (2019), CVC (2019).

Figure 3 Land coverage in the ZRC Pradera.

Table 3 Area and % of land area in the ZRC Pradera

| Code | Name | Área (Ha) | % Área |

|---|---|---|---|

| AF | Árboles frutales | 0,17 | 0,00 |

| AV | Avícola | 0,53 | 0,01 |

| BNDALT | Bosque natural denso alto de tierra firme | 3434,31 | 35,65 |

| CANA | Caña de Azúcar | 2,17 | 0,02 |

| CF | Café | 5,52 | 0,06 |

| CF-PL | Café-Plátano | 10,57 | 0,11 |

| CT | Cítricos | 4,57 | 0,05 |

| EUC | Bosque plantado de eucalipto | 284,20 | 2,95 |

| LG | Lagunas | 2,22 | 0,02 |

| PCU | Pasto natural | 4237,69 | 43,99 |

| RAALT | Rastrojo Alto | 1070,46 | 11,11 |

| VP | Vegetación de Páramo | 558,17 | 5,79 |

| VP-AB | Vegetación de páramo con arbustos | 21,85 | 0,23 |

| VP-AR | Vegetación de páramo con arbóreos | 0,25 | 0,00 |

| VV | Vivero | 0,84 | 0,01 |

Source: Elaborated by the author based on the information of the IGAC (2018)"DANE (20!9)"CVC (2019).

Areas with peasant economy crops such as fruit trees (AF), coffee (CF), the coffee-banana association (CF-PL) and citrus fruits (CT), only represent 0.22% of the area, dispersed in Lomitas, Potrerito, El Nogal and La Fría. It is noteworthy that pasture coverage is not only the main one in the entire ZRC, but 80% is located within the ZRF, with 3,386.25 ha.

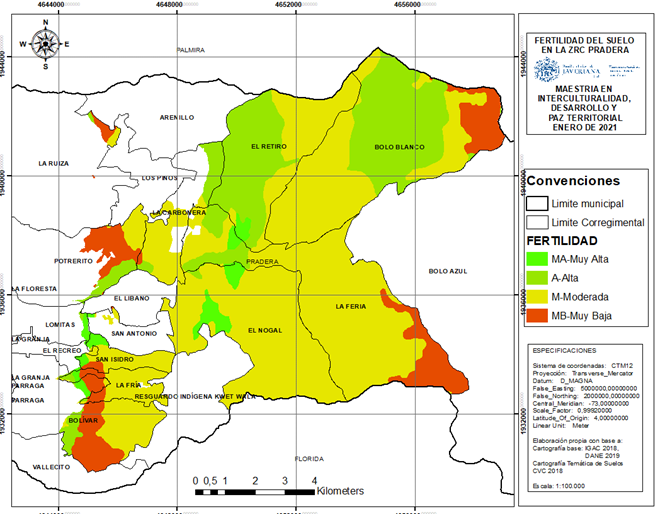

On the other hand, analyzing the fertility of the soil it was found that there are 267.04 ha (2.77% of the area) in the Very High category (MA); in High category (A) there are 2,267.47 ha (23.53% of the area); in Measured category (M) 6,046.41 ha (62.76%); and in Very Low category (MB) there is 1,052.5 8 ha (10.92%). This indicates that in the ZRC there is a fertility between moderate and high (Figure 4).

Source: Elaborated by the author based on the information of the IGAC (2018), DANE (2019), CVC (2019).

Figure 4 Soil fertility in the Pradera ZRC.

Thus, there is an underuse of the land with ideal fertility conditions for the development of family and peasant agriculture, which is being destined mainly for extensive livestock, probably due to the bankruptcy of national agriculture generated by the economic opening of the late twentieth century and the signing of free trade agreements-FTA, as can be inferred from the interview with a leader of La Feria:

The settlers who arrived began to plant coffee, which was the main crop in this region, and many transitory crops: tomatoes, beans, maize, cassava, arracacha; a lot of food. But when these crops were no longer producing anything but losses, they began to switch to livestock (interview 5, October 28, 2020).

The 518.93 ha with Very Low (MB, in Spanish) fertility between La Ruiza, Potrerito, San Isidro, La Fría and Bolívar are striking, since in these areas a significant number of peasants are living in smallholdings, microfundios and small property, in the scarce area that is outside the ZRF. In contrast, most areas with Very High (MA, in Spanish), High (A, in Spanish) and Measured (M, in Spanish) fertility, and where the properties are mainly medium to large, are within the ZRF, as will be seen in the next section. |

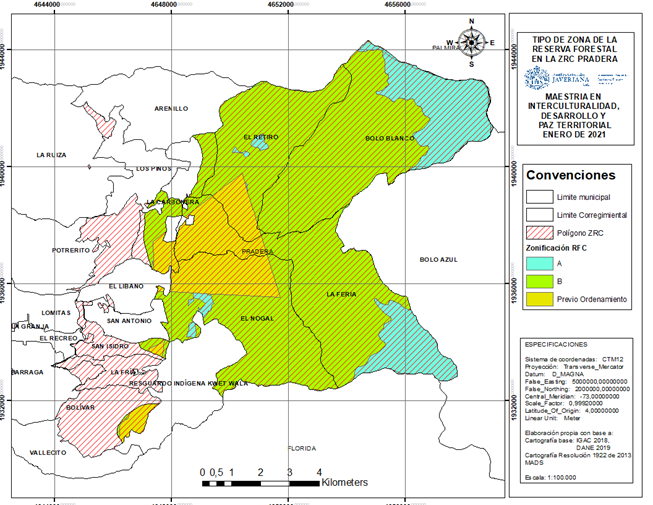

3.5. Legal Appropriation of the Territory by the State: the case of the Forest Reserve of Law 2 of 1959

As anticipated, the ZRC overlaps with the ZRF by 8,210.59 ha, namely 85.22% of the polygon area (Figure 5). Of this area, 1,308.45 ha correspond to a type A zone, or assurance of the supply of ecosystem services; 5,709.44 ha correspond to a type B zone, or sustainable management of forest resources; and 1,192.7 ha correspond to areas with prior definition of ordering, that is, "(.) National Parks, RUNAP areas, Peasant Reserves, Collective and Indigenous Territories, among others, which are within the boundaries of the Reserve, and which retain this category." (MADS, 2013).

Source: Elaborated by the author based on the information of the IGAC ZRC. (2018), DANE (2019), CVC (2019).

Figure 5 Type of Forest Reserve Zone of Law 2 of 1959 in the Pradera

Although peasant colonization has occurred since the early twentieth century, the creation of this figure has prevented the titling of vacant (Presidencia de la República, 1974) and conditioned land uses in accordance with the zoning adopted by MADS Resolution 1922 of 2013. Thus, only 1,422.91 ha of peasant territorial aspiration, where microfundio, smallholdings and small property predominate, are outside this figure that restricts and conditions the OSPR (Presidencia de la República, 2017).

For this reason, the POSPR formulated by the ANT (2019) reported the rural towns of El Nogal, El Retiro, La Feria and Bolo Blanco with restriction throughout their area. In addition, La Carbonera, San Antonio and San Isidro, add an additional area of approximately 600 ha with restriction, so it can be said that more than 50% of the properties with restriction for being in ZRF are within the area proposed to constitute the ZRC.

Consequently, of the 4,788 properties to which the ANT (2019) made the preliminary legal analysis, only 529 that correspond to 5,613.8 ha (15.7% of the total municipal area) were defined as within its competence. One of the reasons why this large number of properties was excluded refers to those duly acquired "(... ) by a private individual, when the ownership is consolidated, does not present a false tradition or act that generates doubt about the ownership and is constituted as a full right of ownership" (p. 100).

In this way, it seems that the ANT when formulating the POSPR ignores the phenomena of uneconomic fractionation and concentration of land ownership that have characterized the territory, in a context of social and armed conflict.

4. Pradera ZRC: Peasant Territory, Disputed Territorialities.

According to the results obtained, it can be affirmed that the mountainous area of Pradera was configured during the twentieth century as a fundamentally peasant territory, despite state abandonment, war, displacement, dispossession, pressure for water exerted by agribusiness and the establishment of environmental management figures that exclude them. This territorial construction, unlike the colonization of the hot lands promoted by the Republican State in the nineteenth century (Palacio, 2006), was led by the same peasantry without any state support, in order to preserve their lives and culture, articulating the municipality to the national dynamics of peripheral colonization, resulting from the everlasting postponement of an agrarian reform (González, 2014).

However, since I960 there has been a series of disputes over the overlapping of three territorialities (Agnew y Oslender, 2010): I) peasant territoriality translated into the ZRC proposal; 2) the ZRF of Law 2 of 1959 as state legal appropriation of the territory; and 3) the model of intensive agro-industrial exploitation of sugarcane, focused on its interest in water. These disputes, added to the social and armed conflict, have generated five conflicts that will arise below.

First, there is the tension over access and equitable distribution of land. In this way, the bimodal nature of the agrarian structure in the study area is confirmed, in correspondence with the high Gini index of rural property demonstrated by the UPRA (2016) for the municipality. A phenomenon that becomes more relevant given the distribution in medium and large farms in the flat rural area, mainly dedicated to sugarcane agroindustry (ANT, 2019).

This generates constant problems between small and large property, in a context of uncertainty about property rights marked by political violence and armed conflict, state weakness and discriminatory policies towards the peasantry. All of which are distinctive elements of the bimodal agrarian structure (Suescún, 2013).

Faced with this tension, it is paradoxical that the ANT (2019) considers the formalized properties out of its competence to attend by offer; because with this decision the phenomena indicated above are ignored, which have especially affected the peasantry, leaving in question the application of the territorial and differential approaches as guiding criteria of the POSPR (Presidencia de la República, 2017). Likewise, it is forgotten that Pradera was included as a PDET municipality to promote "(...) the structural transformation of the countryside and rural areas (...) ensuring well-being and good living, the protection of the multi-ethnic and multicultural wealth, the development of the family and peasant economy..." (MADR, 2017, p.8).

A second tension, which deepens the disadvantages of the peasantry compared to the large landowners, is given by the low fertility of the soil in 36.46% of the study area outside the ZRF. Thus, these communities must not only manage on land well below the UAF, but must also do so in soils that lack the agrological properties to carry out agricultural activities in a profitable manner. This represents an obstacle to the development of the peasant economy and a challenge for the OSPR, since the pressure on these soils will lead to their greater degradation, the loss of their low productivity and, consequently, the greater impoverishment of the families that work them (Fajardo, 2018); which will ultimately result either in a greater uneconomic fractionation of property, or in a greater concentration of land.

In relation to the above, there is evidence of a third tension linked to the impact of economic opening on the peasant economy. Indeed, the signing of Free Trade Agreements with various countries generated a crisis in Colombian agriculture that particularly affected peasant producers (Oxfam, 2009), given the exponential increase in food imports, with prices below the production costs of peasant products. In this way, we understand the transition of agricultural activities towards livestock by the peasantry reflected in the land cover, as it is a more viable economic alternative.

The correction of this phenomenon requires implementing an integral rural reform, with projects to promote the peasant, family and community economy in complement to programs and projects for access and formalization of land, as proposed in the Final Peace Agreement-AFP (Naranjo, Machuca y Valencia, 2020). If this does not happen, POSPRs are likely to end up reproducing the phenomenon of land concentration, by incorporating new areas into an inequitable land market, in which the bankrupt peasantry would be at the mercy of land grabbers.

The fourth tension is presented by the different uses given to the land in the study area and its relationship with the permitted uses, generating problems for access and land tenure. In this sense, the evidence of natural pastures as the main land cover, with a greater incidence within medium and large farms in the ZRF, indicates an important transformation in uses towards livestock activities, contrary to legal provisions.

The transformation of vegetation cover derived from cattle ranching is a multicausal phenomenon with national incidence (Bustamante-Zamudio y Rojas-Salazar, 2018), so its explanation requires specific multidisciplinary studies. In this sense, without being exhaustive, it is identified that the peasant colonization was prior to the creation of the ZRF in 1959, entailing the transformation of the coverages for the development of agricultural activities typical of its economy. This was ignored by the national government when creating this figure, without being corrected so far.

For this reason, it is considered that the decision to exclude the areas of the ZRF from the collection of physical, legal and social information during the preliminary property sweep, considering that they are not subject to the competence of the ANT, violates the guidelines on restrictions and conditions in the formulation of the POSPR (ANT, 2018). In these guidelines, it is indicated that, in the case of properties within the ZRF, some legal processes of the offer can be made viable. In addition, the rights of use and management of the communities that have inhabited them historically are unknown, contrary to the Integral Rural Reform agreed in the Final Peace /Agreement (Naranjo et al., 2020). Likewise, the normative provisions that empower the ANT to request the MADS to subtract areas of Law 2 of 1959 (Decree I777 of I996 and Resolution 629 of 2012), in order to advance rural development programs or land restitution for victims, are forgotten. All this ends up limiting the possibilities of access and equitable distribution of land for the peasantry.

These four conflicts lead to a fifth and final conflict, which can be understood as their synthesis: the population decrease in the rural area of Pradera. Certainly, there is a manifest intention to force the peasant argument of 'agriculture without people' to become a reality; not only by the work and grace of the "capitalist expansion to every corner of the rural sector" (Salgado, 2002, p. 30), but also as a consequence of its violent physical elimination and the normative and institutional adjustment to deny the rights to land and territory of the peasantry.

In this way it is understood that, on the one hand, the POSPR does not question the large states and therefore ends up accepting its legalization and legitimation; and, on the other hand, preservationist objectives are prioritized based on a nineteenth-century anthropocentrism, which contrasts nature and culture (Descola, 2011), to remove the human being from his belonging to nature. Thus, the conservation of ecosystems implies the expulsion of the communities that have historically inhabited them, ignoring their territorial rights and turning the vaunted sustainable development into an unattainable utopia. Quite the opposite of this conception, it is agreed with Angel-Maya (2002) that:

(...) What the environmental perspective urgently requires is a theory that allows man to be an integral part of nature but at the same time to understand his own specificity, because without this specificity it is also impossible to understand the environmental problem. (p. 118).

An example of this is found in Law 1930 of 2018 or Moors Law (Congreso de Colombia, 2018), which does not propose an explicit restriction that calls for displacing the inhabitants who have traditionally and historically inhabited them. On the contrary, it recognizes the social and cultural aspects within the components that make up the moors, as well as the rights to participation of the communities that inhabit them, incorporating an ecosystem and intercultural approach to their management (art. 2). Likewise, it deploys a population approach that opens the possibility for traditional inhabitants to become moorland managers to develop management activities for these ecosystems (art. I6). These and other aspects were highlighted by the Corte Constitucional (2019) making it a benchmark to advance in a territorial planning with a true environmental perspective.

Perspective that understands the cultural system as an evolutionary emergency, whose distinctive feature is the use of instrumentality as an adaptation mechanism, complementing the biological being with the technological base. With the recognition of this specificity, the human being is incorporated into nature, as an expression of its diversity (Ángel-Maya, 2002); which allows, in turn, to recognize the peasantry as a subject of conservation.

These aspects are in line with the conceptualization of the peasantry in Colombia (ICANH, 2020), especially in the territorial dimension, which defines the life of the Colombian peasant subject as "(...) a network of social links expressed in communities, villages, rural towns, mines, beaches, among others, and developed in association with ecosystems... " (p. 20). And also, with the cultural dimension, in relation to their conceptions and knowledge as a fundamental basis for the definition of practices, management and valuations of natural ecosystems.

5. Conclusions

Taking into account these five conflicts identified for the OSPR in the Pradera ZRC, progress will be made towards an order that recognizes the land rights of the peasantry. However, in the POSPR formulated, there is an unjustified inclination of the ANT to only offer help with formalization processes, to the detriment of a true ordering that also implies the access and redistribution of land.

This inclination, added to the lack of articulation with the multipurpose cadaster, distorts the attention based on a "property sweep", conceived in the AFP to develop a comprehensive land policy that addresses socio-territorial conflicts by enhancing new realities (Naranjo et al., 2020). Likewise, it shows the persistence of the institutional disarticulation that has characterized the Colombian agrarian sector (Abril, Valencia, Peña, Abonado, Barrero, Jimenez, Lozano, Triana, y Uribe, 2019), limiting their ability to respond to the challenges of integral rural development and the construction of a stable and lasting peace.

In addition, the recommendations promoted by the international community to achieve the eradication of hunger and poverty in the world and protect the environment are unknown, as is the case of the Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure-DVGT (FAO, 2012), in light of which FAO (2019) highlighted the relevance of the ZRC as a figure that contributes to a "sustainable balanced development, participatory land-use planning, and broad and equitable access to land" (p. 79), and recommended making the necessary adjustments to close the legal and regulatory gaps in the ZRC that guarantee their proper constitution.

In this sense, it is considered that, in order to organize the territory, guaranteeing access and redistribution of land for the peasantry in the area proposed as ZRC in Pradera, the following complementary guidelines should be incorporated into the POSPR:

In the formulation and execution of the POSPR, when there are territorial contexts marked by political violence and armed conflict, as well as phenomena of inequitable distribution of land, the ANT must attend by offer to both large properties and smallholdings and microfundio, even if they are duly formalized, in order to advance processes of equitable redistribution of land, in accordance with current regulations.

The ZRC is a figure of territorial planning that allows the agency of integral rural development from its Sustainable Development Plan. In this sense, when in the formulation of a POSPR it is found that an administrative process of constitution of ZRC is open in the territory, this will be attended by offer to speed up its processing.

Taking into account the territorial and differential criteria, as well as respect for the rights acquired by the communities that have been living within the ZRF, the ANT must contemplate the figure of subtraction of areas of Law 2 of 1959 for the formulation and execution of the POSPR, when the territorial contextualization provides sufficient elements to sustain it.

The POSPR should recognize the peasantry as a subject of environmental conservation, guaranteeing their participation in the environmental management of the territory and encouraging the incorporation of agroforestry and silvopastoral systems within the framework of an agroecological production model

REFERENCES

1. ABRIL, Natalia; VALENCIA, Miltón; PEÑA, Rocío; ABONADO, Alejandro; BARRERO, Camilo; JIMENEZ, María; LOZANO, Alfonso; TRIANA, Bryan; URIBE, Luisa. Laberintos Institucionales: una mirada crítica a los programas de formalización de la propiedad rural en Colombia. Observatorio de Restitución y Regulación de Derechos de Propiedad Agraria [online] Octubre, 2019. 53p. ISSN: 2590-9347. https://www.observatoriodetierras.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/laberintos-institucionales-2.pdf. [ Links ]

2. AGENCIA NACIONAL DE TIERRAS. Plan de Ordenamiento Social de la Propiedad Rural POSPR-Municipio de Pradera. Pradera: Subdirección de Planeación Operativa, 2019171(Inédito) [ Links ]

3. AGNEW John; OSLENDER, Ulrich. Territorialidades superpuestas, soberanía en disputa: lecciones empíricas desde América Latina En: Tabula Rasa. Jul-dic. 2010 no. 13, 191-213. http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/tara/n13/n13a03.pdf. [ Links ]

4. ÁNGEL-MAYA, Augusto. El retorno de Icaro. La Razón de la vida. Muerte y vida de la filosofía. Una propuesta ambiental. 2da. Edición. Bogotá: Panamericana Formas e Impresos, 2002. 323 p. (Serie Pensamiento Ambiental Latinoamericano. PNUD-PNUMA; no. 3). [ Links ]

5. ANZORC; CMDR. Plan de Desarrollo Sostenible de la Zona de Reserva Campesina en Proceso de Constitución Pradera-Valle del Cauca. Pradera, Colombia: Inédito. 2019. [ Links ]

6. BUSTAMANTE-ZAMUDIO, Clarita; ROJAS-SALAZAR, Laura. Reflexiones sobre transiciones ganaderas bovinas en Colombia, desafíos y oportunidades. En: Biodiversidad en la práctica. 2018. vol. 3, no. 1, p. 1-29, http://revistas.humboldt.org.co/index.php/BEP/article/view/516. [ Links ]

7. CENTRO NACIONAL DE MEMORIA HISTÓRICA. "Patrones" y campesinos: tierra, poder y conflicto en el Valle del Cauca (1960-2012). Bogotá D.C: CNMH. 2014. 432 P. ISBN: 973-953-53524-3-3. [ Links ]

3. COLOMBIA. CONGRESO DE LA REPUBLICA. Ley 1930 de 20I3 (27 de Julio de 2013). Por medio de la cual se dictan disposiciones para la gestión integral de los páramos en Colombia. Bogotá D.C, 2018. 14 p. http://es.presidencia.gov.co/normativa/normativa/LEY%201930%20DEL%2027%20 DE%20JULIO%20DE%202013.pdf. [ Links ]

9. COLOMBIA. CORTE CONSTITUCIONAL. Sentencia C-37I/I4. (11 de Junio de 2014). Creación de Zonas de Reserva Campesina. Bogotá: 2014. 93 p. https://www.corteconstitucional.gov.co/relatoria/2014/C-371-14.htm. [ Links ]

10. COLOMBIA. CORTE CONSTITUCIONAL Sentencia C-319 de 2019. Bogotá: 2019. 89 p. https://www.corteconstitucional.gov.co/relatoria/2019/C-369-19.htm. [ Links ]

11. COLOMBIA. INSTITUTO COLOMBIANO DE LA REFORMA AGRARIA. Resolución No. 041 de 1996 (24 de Septiembre de 1996). Determinación de extensiones para las UAF. Diario Oficial Bogotá D.C. : 1996. No. 42910. 46 p. [ Links ]

12. COLOMBIA. MINISTERIO DE AGRICULTURA Y DESARROLLO RURAL. Resolución 000129 de 2017. Lineamientos para la elaboración, aprobación y ejecución de los Planes de Ordenamiento Social de la Propiedad Rural. Bogotá D.C: 26 de mayo de 2017. 48 p. [ Links ]

13. COLOMBIA. MINISTERIO DE AGRICULTURA Y DESARROLLO RURAL. Decreto 393 de 2017. Por el cual se crean los programas de Desarrollo con Enfoque Territorial-PDET (28 de mayo de 2017). Diario Oficial Bogotá D.C.: 2017. No.50.247. 15 p. [ Links ]

14. COLOMBIA. MINISTERIO DE AMBIENTE Y DESARROLLO SOSTENIBLE. Resolución 629 de 2012. Diario Oficial Bogotá D.C.: 2012. No. 48.432. 7 p. [ Links ]

15. COLOMBIA. MINISTERIO DE AMBIENTE Y DESARROLLO SOSTENIBLE. Resolución 1922 de 2013. Por el cual se adopta la zonificación y el ordenamiento de la reserva forestal central, establecida en la Ley 2a de I959 y se toman otras determinaciones. Bogotá, D.C.: 2013. 13 p. [ Links ]

16. COLOMBIA. PRESIDENCIA DE LA REPÚBLICA. Acuerdo final para la terminación del conflicto y la construcción de una paz estable y duradera. Bogotá D.C.: 24 de Noviembre de 2016. 310 p. [ Links ]

17. COLOMBIA. PRESIDENCIA DE LA REPÚBLICA. Decreto 1777 del 1 de octubre de 1996. Por el cual se reglamenta parcialmente el capítulo XIII de la Ley 160 de 1994, en lo relativo a las Zonas de Reserva Campesina. Diario oficial Bogotá D.C: 1996. N. 42892. 2 p. [ Links ]

18. COLOMBIA. PRESIDENCIA DE LA REPÚBLICA. Decreto 2311 de 1974. Código Nacional de Recursos Naturales Renovables y de Protección del Medio Ambiente. Bogotá: 18 de diciembre de 1974. 64 p. [ Links ]

19. COLOMBIA. PRESIDENCIA DE LA REPÚBLICA Decreto Ley 902 del 23 de mayo de 2017 "Por el cual se establecen medidas para facilitar la implementación de la Reforma Rural Integral contemplada en el Acuerdo Final en materia de Tierras". Diario Oficial Bogotá D.C.: 2017, No. 50.248. 29 p. [ Links ]

20. CONTRALORÍA GENERAL DE LA REPÚBLICA. Censo General de Población de 1938. [online], Bogotá: CGR, 1942. 179 p. http://biblioteca.dane.gov.co/media/libros/LD_771_1933_V_1.PDF. [ Links ]

21. CORPORACIÓN AUTÓNOMA REGIONAL DEL VALLE DEL CAUCA. Estudio General de Suelos. [online] Cali: GEOCVC. 2013. https://geo.cvc.gov.co/arcgis/home/item.html?id=437cbbdc7eae47bbaafc52e7f23cc096. [ Links ]

22. CORPORACIÓN PARA EL DESARROLLO REGIONAL. Nos mantuvimos unidos...somos sobrevivientes empoderados del territorio. Reconstrucción de la memoria histórica del conflicto armado y la violencia política en cinco municipios del Valle del Cauca. Santiago de Cali: 2018. 109 p. (Proyecto "Fortalecimiento de organizaciones sociales comunitarias con especial énfasis en sus mujeres para la construcción de paz y la defensa de los derechos humanos en cinco municipios del Valle del Cauca" [Expediente 2017/223630]). [ Links ]

23. DEPARTAMENTO ADMINISTRATIVO NACIONAL DE ESTADISTICA. Censo de Población de 1951 Valle del Cauca. [online], Bogotá: DANE, 1951. 34 p. https://biblioteca.dane.gov.co/media/libros/LB_313_1951_V_1.PDF. [ Links ]

24. DEPARTAMENTO ADMINISTRATIVO NACIONAL DE ESTADISTICA. XII Censo de Población y II de edificios y viviendas. Resumen Valle del Cauca. [online], Bogotá: DANE , 1964. 143 p. https://biblioteca.dane.gov.co/media/libros/LB_303_1964.PDF. [ Links ]

25. DEPARTAMENTO ADMINISTRATIVO NACIONAL DE ESTADISTICA. XIV Censo Nacional del Población y III de Vivienda. Valle del Cauca. [online], Bogotá: DANE , 1973. 592 p. https://biblioteca.dane.gov.co/media/libros/LB_313_1973.PDF. [ Links ]

26. DEPARTAMENTO ADMINISTRATIVO NACIONAL DE ESTADISTICA. Censo nacional de 1985. Cuadros de población total con ajuste final de cobertura por secciones del país y municipios. [online], Bogotá: DANE , 1985. 85 p. https://biblioteca.dane.gov.co/media/libros/LB_3374_1935.PDF. [ Links ]

27. DEPARTAMENTO ADMINISTRATIVO NACIONAL DE ESTADÍSTICA. Censo 1993.Valle. Bogotá: DANE , 1993. http://biblioteca.dane.gov.co/media/libros/LB_313_1993.PDF. [ Links ]

28. DEPARTAMENTO ADMINISTRATIVO NACIONAL DE ESTADÍSTICA. Censo Nacional Agropecuario 2014. [online] , Bogotá: DANE , 2015. https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/agropecuario/censo-nacional-agropecuario-2014. [ Links ]

29. DEPARTAMENTO NACIONAL DE PLANEACIÓN. El campo colombiano: un camino hacia el bienestar y la paz. Informe detallado de la Misión para la transformación del campo. Bogotá D.C.: Nuevas Ediciones S.A. 2015. 318 p. Tomo 1. [ Links ]

30. DEPARTAMENTO NACIONAL DE PLANEACIÓN [online]. Bogotá. Ficha técnica del municipio de Pradera, Valle del Cauca. 2021. https://terridata.dnp.gov.co/index-app.html#/perfiles/76563. [ Links ]

31. DESCOLA, Philippe. Más allá de la naturaleza y de la cultura. En: MONTENEGRO, Leonardo. Cultura y Naturaleza. Bogotá: Jardín Botánico de Bogotá José Celestino Mutis, 2011. 466 p. ISBN: 973-953-3576-03-9. [ Links ]

32. DUARTE, Carlos; CASTAÑO, Alen. Territorios y derechos de propiedad colectivos para las comunidades rurales en Colombia. En: Maguaré. 2020. vol. 34, no. 1, p. 111-147. https://doi.org/10.15446/mag.v34n1.90390. [ Links ]

33. ESTRADA, Jairo. Territorios campesinos. La experiencia de las Zonas de Reserva Campesina. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia (Sede Bogotá). Facultad de Derecho, Ciencias Políticas y Sociales: Instituto colombiano de Desarrollo Rural (INCODER), 2013. 259 p. ISBN: 978-958-761-766-5. [ Links ]

34. FAJARDO, Darío. Experiencias y perspectivas de las Zonas de Reserva Campesina. [Online]. Bogotá: Corporación grupo semillas Colombia, Septiembre 20 de 2014. http://www.semillas.org.co/es/experiencias-y-perspectivas-de-las-zonas-de-reserva-campesina. [ Links ]

35. FAJARDO, Darío. Estudio sobre los orígenes del conflicto social y armado, razones de su persistencia y sus efectos más profundo en la sociedad colombiana. En: ESTRADA Jairo. Conflicto social y rebelión armada en Colombia. Ensayos críticos. Bogotá: Gentes del común, 2015. 95-150 p. ISBN: 973-953-3341-53-3. [ Links ]

36. FAJARDO, Darío. /Agricultura, campesino y alimentos (1980-2010). Tesis de grado para optar al titulo de Doctor en Ciencias Sociales. Bogotá D.C.: Universidad Externado de Colombia. Facultad de Ciencias Sociales y Humanas. 2013. 299 p. [ Links ]

37. GARCIA, Antonio. Reforma Agraria y Desarrollo Capitalista en América Latina. Bogotá: Centro de Investigaciones para el Desarrollo, 1986. 131 p. 33. [ Links ]

38. GOBERNACIÓN DEL VALLE DEL CAUCA. Atlas "conflicto armado y perspectivas para la paz en el Valle del Cauca. Santiago de Cali: Alta Consejería para la Paz y los Derechos Humanos. 2015. 55 p. [ Links ]

39. GONZÁLEZ, Fernán. Poder y violencia en Colombia. Bogotá D.C.: Odecofi-Cinep, 2014. 583 p. ISBN 9789586442015. [ Links ]

40. GUEREÑA, Araxanta. Radiografía de la desigualdad. Lo que nos dice el último censo agropecuario sobre la distribución de la tierra en Colombia. [online] Oxfam-América, 4 de julio de 2017. 33 p. https://oi-files-d3-prod.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/file_attachments/radiografia_de_ la_desigualdad.pdf. [ Links ]

41. HERNÁNDEZ-SAMPIERI, Roberto; FERNÁNDEZ-COLLADO, Carlos; BAPTISTA-LUCIO, Pilar. Metodología de la Investigación. 6a Edición. México D.F: McGraw-Hill, 2014. 600 p. [ Links ]

42. INSTITUTO COLOMBIANO DE ANTROPOLOGIA E HISTORIA-ICANH. Conceptualización del campesinado en Colombia. Documento técnico para su definición, caracterización y medición. Bogotá: Marta Saade Granados, ed., 2020. 172 p. (Colección: Cuestiones & Diálogos). ISBN: 978-958-8852-87-4.Entramado Vol. 19 No. 1, 2023 (Enero - Junio) [ Links ]

43. INSTITUTO DE ESTUDIOS INTERCULTURALES DE LA UNIVERSIDAD JAVERIANA DE CALI; DEJUSTICIA; COMISIÓN COLOMBIANA DE JURISTAS. Investigación de patrones de violencia campesinos. Santiago de Cali: Documento de Trabajo del IEI, (sf) (INÉDITO). [ Links ]

44. INSTITUTO GEOGRÁFICO AGUSTÍN CODAZZI. Datos abiertos catastro. [online] . Subdirección de catastro, 2020. https://geoportal.igac.gov.co/contenido/datos-abiertos-catastro. [ Links ]

45. MANÇANO, Bernardo. El enfoque socioterritorial. [online] Programa Social Agropecuaria-PSA. 2006 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tzT-IDujJ9AM&t=IIs. [ Links ]

46. MINISTERIO DE AGRICULTURA. Guía Lineamiento sobre restricciones y condicionantes en la formulación de los POSPR. VI. [online] , Agencia Nacional De Tierras, 2013. 34 p. https://www.agenciadetierras.gov.co/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/POSPR-G-010-LINEAMIENTO-RESTRICCIONES-Y-CONDICIONANTES.pdf. [ Links ]

47. NARANJO, Sandra; MACHUCA, Diana; VALENCIA, Marcela. La Reforma Rural Integral en Deuda. Bogotá: Gentes del común , 2020. (Colección Cuadernos de la Implementación, no. 6.) [ Links ]

48. ORDOÑEZ-GÓMEZ, Freddy. Zonas de Reserva Campesina. Informe de Derechos humanos y derecho internacional humanitario 2013. . Bogotá D.C.: ILSA 2014. 66 p. http://ilsa.org.co/documentos/INFORME_DDHH_ZRC_CENTRAL_2013.pdf. [ Links ]

49. ORGANIZACIÓN DE LAS NACIONES UNIDAS PARA LA ALIMENTACIÓN Y LA AGRICULTURA-FAO. Tenencia de la tierra y desarrollo rural. Roma: FAO, 2003. 62 p. (Estudios sobre tenencia de la tierra, no. 3). ISBN 92-5-304346-3 https://www.fao.org/3/y4307s/y4307s.pdf. [ Links ]

50. ORGANIZACIÓN DE LAS NACIONES UNIDAS PARA LA ALIMENTACIÓN Y LA AGRICULTURA-FAO. Directrices voluntarias sobre la gobernanza responsable de la tenencia de la tierra, la pesca y los bosques en el contexto de la seguridad alimentaria nacional. Roma: FAO , 2012. 43 p. ISBN 973-92-5-307277-4 https://www.fao.org/3/i2301s/i2301s.pdf. [ Links ]

51. ORGANIZACIÓN DE LAS NACIONES UNIDAS PARA LA ALIMENTACIÓN Y LA AGRICULTURA-FAO. Laz Zonas de Reserva Campesina: retos y experiencias significativas en su implementación. Bogotá: FAO, 2019. 509 p. ISBN 978-92-5-130799-1. https://www.fao.org/3/CA0467ES/ca0467es.pdf. [ Links ]

52. OXFAM-AMÉRICA. Tratado de Libre Comercio entre Estados Unidos y Colombia. Impactos sobre la agricultura y la economía campesina. [Online]. Corporación grupo semillas Colombia, 23 de octubre de 2009. https://www.semillas.org.co/es/tratado-de-libre-comercio-entre-estados-unidos-y-colombia-impactos-sobre-la-agricultura-y-la-econom. [ Links ]

53. PALACIO, Germán. Fiebre de tierra caliente. Una historia ambiental de Colombia. 1850-1930. Bogotá, D.C: ILSA, 2006. XX 183 p. Colección En Clave Sur. ISBN 9539262305. [ Links ]

54. PROGRAMA DE LAS NACIONES UNIDAS PARA EL DESARROLLO-PNUD. Colombia rural. Razones para la esperanza. Informe Nacional de Desarrollo Humano 2011. Bogotá: INDH PNUD, 438 p. ISBN: 978-958-8447-63-6. [ Links ]

55. RODRIGUEZ, Bladimir; RINCÓN, Laura. Apuntes metodológicos para el análisis espacial de conflictos territoriales. Bogotá, D.C.: GeoRaizAl, 2018. 35 p. Proyecto del equipo del programa de Geografía: especialización en análisis espacial en conflictos territoriales, Universidad Externado de Colombia(Inédito) . [ Links ]

56. SALGADO, Carlos. Los campesinos imaginados. Bogotá: ILSA, 2002. 41 p. (Cuadernos Tierra y Justicia no. 6) ISBN 958-9262-22-8. [ Links ]

57. SUESCÚN-BARON, Carlos Alberto. La inercia de la estructura agraria en Colombia: determinantes recientes de la concentración de la tierra mediante un enfoque espacial. En: Cuadernos de economía[online] , 2013; vol. 32, no. 61, 653-632 p. ISSN 0121-4772. http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo. php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0121-477220I3000300002&lng=en&nrm=iso. [ Links ]

53. UNIDAD DE PLANIFICACIÓN AGROPECUARIA-UPRA. Análisis de la distribución de la propiedad rural en Colombia. Propuesta metodológica. Bogotá D.C: UPRA, 2016. 583 p. [ Links ]

59. VALDIVIA ROJAS, Luis. Mapas de densidad de población para el suroccidente, 1343-1370. Historia y Espacio[online] , 1930; no. 5, 103-110 p. https://doi.org/10.25100/hye.v015.5322 [ Links ]

* ORDOÑEZ-BOTERO, Harold. Peasant Occupation and Use of the Land in the Municipality of Pradera (1900-2010): A century of socio-territorial tensions. In: Entramado. January-June, 2023 vol. 19, no. 1, e-8644 p. 1-17 https://doi.org/10.18041/1900-3803/entramado.1.8644

Received: April 28, 2022; Accepted: October 15, 2022

text in

text in