1. Introduction

Some of the contemporary debates in the world of work and organizations have placed new ways of working that account for a new configuration of organizations under the paradigm of flexibility (Antunes, 2001; De la Garza, 2000; Soto, 2008; Stecher, 2015). This configuration has implied a transition from the so-called "standard" or "traditional" jobs to "atypical" or "non-standard" jobs, which blur the rules of long-term contracting, working hours, subordination practices, office work, and presence, among others (Antunes, 2001; Areosa, 2021; De la Garza, 2000, 2009). Although these forms of work have been occurring in various economic sectors and industries worldwide, some authors have focused their attention on jobs that are framed in the so-called "Gig Economy" (Aloisi, 2016; Ashford, Caza, and Reid, 2018; De Stefano, 2016; Kirven, 2018; Méda, 2019; Todolí-Signes, 2017; Woodcock and Graham, 2020).

The jobs developed in this economy are characterized by being short-term, sporadic, independent, and autonomous (Areosa, 2021; Davis and Sinha, 2021). These have been positioned within the category of "non-standard jobs" because they involve a fragmented relationship and outside of what has traditionally implied an employment relationship. (Aloisi, 2016; Berg, Furrer, Harmon, Rani, & Silberman, 2018; Cornelissen & Cholakova, 2019; De Stefano, 2016; Duggan, Sherman, Carbery, & McDonnell, 2020; Kirven, 2018; Méda, 2019; Schmidt, 2017; Todolí-Signes, 2017; Woodcock & Graham, 2020). Most of these jobs are mediated by online platforms that digitally connect workers or individuals providing services with consumers, which can be performed in the cloud or specific geographic locations (Areosa, 2021; CEPAL and OIT, 2021; Duggan et al., 2020; Kirven, 2018; Meijerink and Keegan, 2019; Woodcock and Graham, 2020).

Gig Economy jobs have spread exponentially in different countries around the world thanks to the development of technological platforms, which have become easy access and performance strategies for income generation. According to some consulting firms, about 35% of workers in the United States work independently, and it is estimated that by 2027 this independent workforce will be the one with the highest participation (CEPAL and OIT, 2021; Deloitte, 2020; Digital Future Society, 2019; Upwork, 2020; World Economic Forum, 2020).

How the Gig Economy has been organizing and transforming the labor market and productive sectors has led different authors to reflect on the role of human resources management (from now on HR) in this context. From a strategic perspective, HR management is responsible for contributing to the performance of the employee and the company through a series of practices that are developed in terms of time and the employment relationship (Allen and Wright, 2007, Boocock, Page-Tickell, and Yerby, 2020; Boxall, Purcell and Wright, 2007 Connelly, Fieseler, Cerne, Giessner, and Wong, 2021; Guthrie, 2001; Hauff, Alewell, and Hansen, 2014; Kepes and Delery, 2006; Lepak and Snell, 1999, 2002).The question then arises, what is their role and configuration in the Gig Economy, if workers do not have an employment contract and are linked in the short term or sporadically with multiple organizations?

Considering that the disruptive trends of the Gig Economy have an impact on the management of organizations and specifically on HR management, this article proposes to reflect on the role and configuration of HR management in this context. To this end, the following objectives are developed:

To present some of the theoretical approaches in the specialized literature on HR management to explain its role and how its practices are combined and configured to contribute to the performance of an organization. (Lepak and Snell, 1999, 2002; Luo et al., 2021;Tsui, Pearce, Porter, and Tripoli, 1997).

Identify the challenges of Gig Economy companies in terms of HR management and the practices that have been researched on this topic according to the academic literature.

Establish a theoretical approach to analyze the role and configuration of HR management in the Gig Economy.

The article is organized in four sections. First, a contemporary definition of HRM is presented. Next, some positions recorded in the academic literature on the role of HRM in the Gig Economy are described. Third, an analysis of the role of HRM in the Gig Economy from the contingent configurational approach is presented, and finally, conclusions and future lines of research are drawn.

2. Human Resource Management: a contemporary approach

HRM is defined as the set of policies and practices that organizations use to attract, develop, and retain their workforce to support and help advance the organization's mission, goals, and strategies (Cascio, 2015; Garcia, 2009). From a strategic and contemplative orientation on which this definition is circumscribed, there is the position to argue HR management as a key player in the organization for being a source of competitive advantage (Becker and Huselid, 2006; Buller and McEvoy, 2012; Jackson, Schuler and Jiang, 2014; Lengnick-Hall, Lengnick-Hall, Andrade and Drake, 2009).

Among the lines of research recognized from a strategic orientation is the interest in understanding how HR practices are configured or grouped to contribute to company performance (Becker and Huselid, 2006; Lengnick-Hall et al., 2009). Different researchers have argued that any organization must choose and design the relevant components of its HRM that provide not only a horizontal fit (i.e., alignment and complementarity of its HR practices) but also achieve a vertical fit (i.e., alignment between HRM and the organization's strategy) to achieve the desirable organizational outcomes (Chang and Chen, 2011; Delery and Doty, 1996). In this direction, Delery and Doty (1996) proposed three approaches to analyze the degree of "internal fit".

The first approach is known as the universal approach, which formulates the assumption that HR practices can be categorized into a set of "best practices" that happen to be appropriate for all contexts (Buller and McEvoy, 2012: Delery and Doty, 1996; Jiang et al., 2012). Under this approach, different authors propose that there are several sets of best practices that, aimed at achieving different results, are appropriate for all contexts (Jiang et al., 2012), can apply to all companies, for example, practices grouped in high-performance HR systems (Shih, Chiang and Hsu, 2006; Huselid, 1995; Macduffie, 1995) in high-commitment HR systems (Allen, Ericksen and Collins, 2006; Huselid, 1995; Macduffie, 1995). (Allen, Ericksen, & Collins, 2013; Arthur, 1994) in high-involvement HR systems- (Allen, Ericksen and Collins, 2013; Arthur, 1994) (Guthrie, 2001) in high investment HR systems -high investment HR systems- (Lepak, Taylor, Tekleab, Marrone, and Cohen, 2007) or in control-oriented HR systems (Arthur, 1994).

The second approach is the contingent approach, which holds that the set of HR practices should be selected based on an appropriate "fit" with other organizational factors, for example, the company's strategy, which in turn is influenced by the characteristics of the environment (Delery and Doty, 1996). From this perspective, it is understood that for organizations to achieve a good "vertical fit", HR practices must be aligned with the company's strategy and the characteristics of the environment (Sels et al., 2006).

Finally, the third approach is known as the configurational approach, which states that organizations can have different ideal HR systems. Thus, if an organization's HR practices are closely aligned with an ideal type and, in addition, are consistent with the organization's competitive strategy, then they would achieve superior performance. (Gould-Williams, 2003). This approach is consistent with the approach of several authors who distinguish the importance of a differentiated HR architecture (Luo et al., 2021) where the use of multiple HR systems, not only across different organizations, is recognized (Lepak and Snell, 1999, 2002; Tsui et al., 1997) but also within the same organization (Becker and Huselid, 2006). In both cases, different configurations of HR practices consider both the contributions that different groups of workers can make to organizational performance (Lepak and Shaw, 2008) and the potential of these HR systems to produce different outcomes (Lengnick-Hall et al., 2009).

In line with the configurational approach and HR architecture, Lepak and Snell (1999) put forward the view of a contingent configurational approach in the context of strategic HRM. For these authors, there is little likelihood that universal HR systems will be appropriate in all situations. Therefore, they argue that the configuration of HR practices depends more on the specificity of human capital and labor relations, assuming that employees should be supported through a differentiated HR architecture (Lepak and Snell, 1999; 2002). In that sense, it is suggested that different levels of human capital should be managed differently in terms of their employment modes, labor relations and different HR configurations (Luo et al., 2020).

Following the proposal of Lepak and Snell (1999) the levels of human capital that influence the categorization of HR practices are classified in terms of two dimensions: according to their value (i.e., the potential that workers have to create value and their associated costs) and their uniqueness (i.e., the specificity that workers have for the firm) (Lepak and Snell, 1999; 2002; Luo et al., 2020).

Because the extent of human capital value and uniqueness can vary, Lepak and Snell (1999; 2002) posit at least four alternative HRM configurations that organizations can (or should) implement to manage groups of workers with different levels of human capital. First, for human capital with high value and high uniqueness, i.e., for workers perceived as valuable and unique, organizations should adopt a knowledge-based mode of employment that emphasizes internal development and long-term commitment. Second, for human capital with high value and low uniqueness, organizations should adopt an 'acquisition'-based employment mode (also known as work-based employment mode) with a 'symbiotic' employment relationship and a 'market-based' HR configuration (also referred to as a productivity-based HR configuration). Although the authors recognize that the group of workers in this category can contribute to the success of the firm, their skills are largely transferable. Therefore, these workers are hired to perform predetermined tasks. Third, for human capital with low value and low uniqueness, where workers are not conceived as strategically important or unique, organizations should adopt a 'contractual' mode of employment (also known as contractual labor agreements) with a 'transactional' employment relationship and a 'compliance' HR setup. In this case, jobs in this group are often outsourced. Finally, fourth, for human capital with low value but high uniqueness, i.e., relatively unique workers but with little strategic value to employ internally, organizations should adopt an employment model under alliances or partnerships, with a 'partnership' employment relationship and a 'collaborative' HR configuration.

The idea that organizations adopt a certain HR configuration has been supported in various studies from different regions, economic sectors, and types of organizations (Cooke, Xiao and Xiao, 2020 Luo et al., 2021). For example, Lepak et al., (2007) found that the service companies included in their study implemented more high-investment HR systems for the company's key employees than for support employees. Toh, Morgeson and Campion (2008) found five alternative HR management systems where labor relations are grouped: two extreme systems, one oriented to maximizing commitment and one oriented to minimizing costs, and three intermediate systems (contingent motivators, competitive motivators, and resource creators). Additionally, the idea of a differentiated HR configuration in recent studies when dealing with different categories of employees, e.g., between managerial and non-managerial employees (Gottschalck, Guenther and Kellermanns, 2020; Sarac, Meydan and Efil, 2017), or between employees who are members of the family that owns the company and employees who are not family members (Jennings, Dempsey, and James, 2018).

Finally, two challenges add to the interest in understanding how different groupings of HR practices contribute to company performance. On the one hand, if the same organization has different HR practices and people perceive reality differently, not all employees will likely similarly interpret HR systems (Liao, Toya, Lepak, & Hong, 2009; Nishii, Lepak, & Schneider, 2009). Therefore, it is required to distinguish the HR system as implemented (i.e., what managers put into practice) and the perceived HR system (i.e., how employees interpret the practices) (Den Hartog, Boon,Verburg, & Croon, 2013). Employees' perception of HR management will mediate the effect of implemented HR practices on organizational performance.

On the other hand, it is complex to assign a particular performance criterion to define HR management (Jiang et al., 2012). It is practically impossible to configure systems that simultaneously maximize a wide variety of performance objectives (Chadwick, 2010). For example, certain configurations have been suggested to meet the objectives of employee engagement, skill enhancement, motivation enhancement, and cost minimization (Arthur, 1994; Lepak and Snell, 1999; Tsui et al. 1997). Thus, HR configurations seek to increase commitment to group practices such as recruitment, socialization, and training (Tsui et al., 1997). Similarly, high-performance HR practices have also been effective in increasing employee commitment (Huselid, 1995). To increase skill levels, selective selection, training, and knowledge- or skill-based incentives become important. Tsui et al. (1997) referred to this configuration as the "overinvestment" or "mutual investment" approach.

The cost minimization objective, whereby investment-intensive HR practices, such as training, or employee engagement opportunities, are avoided, but performance-based incentives are used effectively, has also been advanced (Toh et al., 2008). Tsui et al. (1997) also identified this approach as an "underinvestment" or "spot contract" approach.

Therefore, the differences in HR configurations can not only be distinguished by the levels of human capital to be managed, but also by the objectives that each configuration seeks to achieve, which attracts various explanations that may complement or even differ according to the selected theoretical foundations, the levels of analysis used, the measures used in the studies to capture both HR practices and organizational outcomes, and the particularities of the context (Buller and McEvoy, 2012; Lengnick-Hall et al., 2009). Special emphasis will be placed on contextual particularities in the following section, taking into account the challenges that the context of companies in the Gig Economy has recently offered to researchers in the field of HRM.

3. Human Resource Management in the Gig Economy: some approaches from the academic literature

With the evolution of strategic HR management as a field of knowledge, studies have expanded to understand and evaluate, among other things, how the configuration of different HR policies and practices fit in different contexts as a contingent factor. In this direction, several authors have proposed new approaches to the notion of HR management in the context of the Gig Economy.

One of the main points that have prompted the development of a review of this topic stems from the fact that Gig Economy jobs fracture the standard employment relationship between employees and employers, which has traditionally been used to define the activities that HR management seeks to maintain and enhance (Meijerink and Keegan, 2019). In addition to this, the platforms or applications that companies use in this context to link their workforce operate under algorithms that sometimes replace the activities that are commonly performed by HR management (Duggan et al., 2020; Meijerink and Keegan, 2019).This has led to questioning not only the role of HR management in organizations but also the profession itself (Boocock et al., 2019; Duggan et al., 2020).

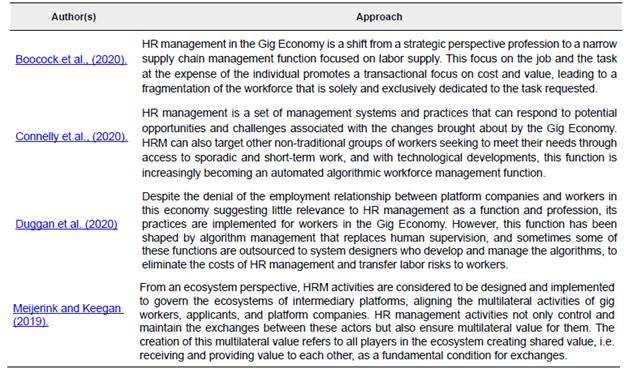

Despite more than l0 years of research that has addressed the Gig Economy, few publications focus on the topic of HR management (Boocock et al., 2020; Connelly et al., 2021; Duggan et al., 2020; Meijerink and Keegan, 2019).Table 1 presents some approaches identified in the academic literature:

According to the approaches to the notion of HR management presented in the table above, this function is in the context of the Gig Economy, albeit under the paradox of avoiding establishing an employment relationship with workers (Boocock et al., 2020; Meijerink and Keegan, 2019;Woodcock and Graham, 2020). For some authors, one of the main activities installed in intermediary platforms is that of workforce planning to match supply with demand for services or tasks (Connelly et al., 2021; Meijerink and Keegan, 2019; Schroeder, Bricka and Whitaker, 2021; Schulte, Schlicher, and Maier, 2020) which is mainly developed thanks to the management of algorithms (Connelly et al., 2021; Duggan et al., 2020; Hyers and Kovacova, 2018).

For Meijerink and Keegan (2019), HRM in the Gig Economy can be defined from an ecosystemic perspective to understand how on-demand or sporadic work is controlled through HRM activities designed and implemented on intermediary platforms. Among the HR management activities that are installed in intermediary platforms is workforce planning, which enables the matching of users who demand services and tasks with those who provide them. Likewise, these authors identify other activities such as the design of jobs, which gives workers the autonomy to work when they wish; performance management, which is evaluated using the same platforms, and which in turn makes it possible to control the worker as well as to compensate him and grant benefits to remunerate his efforts.

Like Meijerink and Keegan (2019), other authors have explored HR management activities in the Gig Economy, concurring with the recognition of the mediating role of algorithm management (Boocock et al., 2020; Connelly et al., 2021; Duggan et al., 2020; Hyers and Kovacova, 2018).The following table presents the HR management activities in the Gig Economy identified in the academic literature:

According to the information presented in Table 2 it is possible to group HR activities into five categories:

Position design and workforce planning: the objective of this activity is to guarantee a supply of workers that meet the requirements of the services and tasks demanded by the customers of the applications. To this end, the algorithms with which the applications are designed allow the geographic and virtual location of users and workers to match them. This means that this function seeks to avoid an imbalance in the market in terms of supply and demand and to guarantee multilateral value for the actors involved in the transaction: the application company, the users (customers), and the workers.

Recruitment and selection: to ensure a balance between supply and demand, the recruitment process is aimed at both workers and users. To this end, the companies that own the applications carry out advertising campaigns in which they offer opportunities to generate income through flexible and easily accessible jobs while encouraging users to use their services. Through the applications, interested users apply for admission and their requirements are automatically verified by algorithms that define their admission. This process blurs some of the traditional stages and techniques used for selection processes, as the selection process is reduced to the verification of information and acceptance to provide services and fulfill tasks, which in some cases are not complex to perform.

Performance management: this process is mainly mediated and controlled by the platforms' algorithms and user ratings. Likewise, ratings can be accompanied by comments and references that could help improve the worker's reputation or, on the contrary, affect the demand for their services and tasks. This information is also managed by the algorithm that in case of bad ratings can block, punish, or expel a worker from the platform. Conversely, good ratings can be managed in favor of compensation and benefits, or increased assignment of tasks.

Compensation and benefits: In the Gig Economy, the economic income depends exclusively on the services rendered or tasks performed. The variation in income depends on the time spent working, the economic incentives defined by the application and the speed at which the services are provided. This income is not regulated in most cases by labor laws, as there is no formal and legal link between the workers and the intermediary platform company. Some intermediary platforms offer benefits to workers based on the fulfillment of goals or performance in established periods, which may be financial coupons or discounts. The algorithms of intermediary platforms are increasingly seeking to improve psychological tactics to encourage the behavior of workers to the image of the company owning the platform that they provide to users.

Training and development: this activity is aimed at improving the qualifications obtained by workers through the platforms and income. Many of the training and development programs promoted in the Gig Economy are short before starting work since the tasks performed are not considered to be complex. In addition to this, training is oriented to the handling of intermediary platforms and to the fulfillment of times that are managed and controlled by algorithms. In this context, time is a fundamental resource, since it is a function of the income that workers can generate and the satisfaction of users.

4. Towards a Human Resources management configuration in the context of the Gig Economy

While the strategic role of HR management in the context of the Gig Economy has been questioned due to the ambiguity involved in creating a competitive advantage from workforce management in a context where there are no labor relations (Allen and Wright, 2007; Boocock et al., 2020; Boxall et al., 2007; Connelly et al., 2021; Lepak and Snell, 1999, 2002), it is possible to argue for the existence of a new HR configuration in this context that seeks the management and organization of work outside standard labor relations.

The HR architecture model proposed by Lepak and Snell (1999; 2002) has become the conceptual model par excellence among contingent configuration approaches in strategic HRM, notably influencing research since its formulation (Luo et al., 2020). Even though the model has been widely cited by subsequent research in the last twenty years and most of the main ideas of the model have been theoretically developed, empirically verified, and/or criticized and extended (Cooke et al., 2020; Luo et al., 2020), the original model has not yet been discussed for understanding HRM in the context of the Gig Economy.

In terms of Lepak and Snell (1999; 2002) not all employees possess knowledge and skills that are equally valuable to a particular organization. Therefore, HR management, modes of employment and employment relationships should be responsive to different levels of human capital. Under this model, a traditional employment relationship is considered, contrary to the one established in the context of the Gig Economy, where a relationship outside employment is ultimately sought, i.e., a workforce to fulfill specific tasks (Areosa, 2021; Davis and Sinha, 2021).That is why most of the workforce in this economy does not apply to the notions of employment relationships established by the authors. However, it is possible to explain an exclusive configuration based on the non-standard work relationship identified in the literature and, with this, to make a logical assumption of the HR configuration under the foundations of the model.

According to the literature on HR management in the context of the Gig Economy, non-standard working relationships between firms and gig workers forge a transactional and symbiotic relationship based on the utilitarian premise of mutual benefit (in terms of Lepak and Snell, 1999; 2002), where the workforce is solely and exclusively engaged in a requested task (Boocock et al., 2020). Both relationships are even manifested by Lepak and Snell (1999) as very similar labor relationships.

In essence, a transactional relationship between worker and organization focuses on the task to be performed, the outcomes to be achieved, and the terms of the agreement (Lepak and Snell 1999). In the context of the Gig Economy, intermediary platforms are responsible for the planning and control of the workforce to match supply with demand for services or timely tasks required (Meijerink and Keegan, 2019). A symbiotic relationship, on the other hand, is based on the notion that both the worker and the organization are likely to continue the relationship as long as both continue to benefit (Lepak and Snell, 1999). This type of relationship assumes that the worker is perhaps less committed to the organization and more career-focused, which makes sense considering that in the context of the Gig Economy, the worker can participate whenever they wish, with the encouragement to meet their needs by accepting sporadic tasks across multiple platforms (Connelly et al., 2020; Meijerink and Keegan, 2019).

Although the transactional and symbiotic relationships are similar (Lepak and Snell, 1999), their differences essentially boil down to the extent of participation and the expectations underlying the exchanges. With the symbiotic relationship, organizations attempt to seek continuity and loyalty, albeit in a limited way. In contrast, with the transactional relationship, firms probably do not expect (and do not obtain) organizational commitment; the relationships simply focus on the economic nature of the "contract." In the context of the Gig Economy, these differences virtually disappear given the sheer complexity of securing a gig worker's commitment to the exclusive use of a single intermediary platform to perform his or her job.

Therefore, this transactional and symbiotic approach would contemplate the assumption that in the context of the Gig Economy the workforce, in terms of human capital, would be perceived with less levels of uniqueness, but a continuous level of plus-minus value, i.e. workers whose skills are largely transferable through automated algorithms, but who can contribute -or not- to the success of the company. Thus, gig workers, who perform sporadic and short-term tasks predetermined and organized by intermediary platforms to match supply and demand for services or tasks (Conelly et al., 2020; Meijerink and Keegan, 2019), can contribute to the success of the firm owning the intermediary platform.

As transactional and symbiotic relationships are similar, so are their respective HR configurations. Following the model of Lepak and Snell (1999; 2002), for the Gig Economy context, a market-oriented (or productivity-maximizing) and compliance-oriented (in terms of Lepak and Snell, 1999; 2002) HR configuration would predominate. A market-oriented configuration emphasizes the recruitment and selection of people who already possess the necessary skills to fulfill certain functions or tasks. In addition, individuals may have discretion and decision-making power. Once hired, they are likely to be allowed a greater degree of empowerment to carry out their tasks. This is why academic literature on the Gig Economy highlights HR practices such as position design workforce planning, and recruitment and selection (Boocock et al., 2020; Connelly et al., 2020; Deng and Joshi, 2016; Fieseler et al., 2019; Meijerink and Keegan, 2019; Mojeed-Sanni and Ajonbadi, 2019; Schroeder et al., 2021; Schulte et al., 2020), while little is discussed on training and development (Kost et al., 2019; Meijerink and Keegan, 2019).

In the compliance-based setup, companies are likely to focus on enforcing rules and regulations, maintaining specific provisions regarding work protocols, and ensuring compliance with preset standards, which is possible with workforce planning and task assignment (Boocock et al., 2020; Connelly et al., 2020; Deng and Joshi, 2016; Duggan et al., 2020, Fieseler et al., 2019). In addition, performance evaluation and rewards will be work-based, focusing on prescribed procedures or specific outcomes, or both; as is the case with ratings and referrals managed by platform algorithms, which while impacting pre-averages and benefits, could also involve punishments or expulsion from the workforce (Duggan et al., 2020; Guda and Subramanian, 2019; Malos et al., 2019; Meijerink and Keegan, 2019).

For both configurations, training and development are virtually zero given that these workers possess skills that are not unique to a particular firm (Kost et al., 2019; Meijerink and Keegan, 2019), so firms may not get a return on any investment in training if workers have an easy time leaving (Lepak and Snell, 1999).

In terms of Toh et al. (2008) and Tsui et al. (1997), the above configuration is consistent with the objective of cost minimization, whereby investment-intensive HR practices such as training, or employee engagement opportunities are avoided, but performance-based incentives are used effectively (Toh et al., 2008). The above agrees in turn, with students in the academic literature evidencing performance management, and compensation and benefits as main HR practices in the Gig Economy (Boocock et al., 2020; Connelly et al., 2020; Deng and Joshi, 2016; Duggan et al., 2020 Jabagi et al., 2019; Malos et al., 2018; Meijerink and Keegan, 2019).

The above shows how an exclusive HR configuration predominates for companies belonging to the Gig Economy context, which is not detached from the strategic approach coined in the literature, especially if we consider that the workforce in this context, and terms of human capital, is conceived a priori with less levels of uniqueness, but with a continuous level of plus-minus value.

5. Conclusions

Taking stock of the knowledge presented, this article has offered a look at the role and configuration of HR management in the context of the Gig Economy. The literature on strategic HR management recognizes the importance of studying how HR practices are configured or grouped to contribute to the performance of companies. As presented in previous sections, this configuration can be explained under the human capital approach as suggested by the HR architecture model proposed by Lepak and Snell (1999; 2002). However, the adoption of a given configuration should not only be based on the strategic value of the workforce within an organization but also the situation established by the context. In this sense, it is imperative to situate the HR configuration according to the particularities of the context in which the companies are immersed. Hence, the discussion will be developed from a contingent approach to argue how HR management is configured in the context of the Gig Economy.

Although the discussion initially agrees with the position of Lepak and Snell (1999; 2002) who emphasized the importance of differentiated HR management for employees with different levels of human capital to make optimal contributions to the company, the context of the Gig Economy poses a unique configuration in organizations where traditional employment modalities and work configurations based on collaboration and long-term commitment are blurred. In this sense, the first starting point for HR management in the Gig Economy is to manage the workforce without incurring the establishment of a standard employment relationship and to prioritize practices aimed at having a workforce with the necessary skills to fulfill the tasks, to connect the demand for tasks with the supply of jobs, to reduce costs, and to ensure the control and fulfillment of the work.

That is why the academic literature has recorded position design and workforce planning, recruitment and selection, performance management, compensation and benefits, and sparsely, training and development as the main HR practices of the Gig Economy (Connelly et al., 2021; Meijerink and Keegan, 2019; Schroeder et al., 2021; Schulte et al., 2020).

As a consequence, and in response to the question of whether in the Gig Economy, there is a new configuration of HR management, it is possible to argue the existence of a predominance of a market-oriented and compliance-oriented configuration, following the proposal of Lepak and Snell (1999; 2002). This is explained by the fact that the aim is to have a workforce with the necessary skills to meet the demand in terms of tasks, and because the mechanisms orchestrated by the algorithms of the platforms establish the conditions for tasks to be fulfilled according to established protocols and standards, and thus compensation and performance can be managed.

While the original HR architecture model is influential (Cooke et al., 2020; Luo et al., 2020), its assumptions prove partial in explaining this reality, so this discussion has revealed gaps and challenges for future research. Several directions for future research are described below. First, it is imperative that future studies empirically validate whether the marketand compliance-oriented HR configurational model, as opposed to other types of configurations, excels in the context of the Gig Economy. If the HR literature recognizes the use of multiple HR practice systems, not only across different organizations but also within the same organization, will there be different practice groupings within different companies operating in the gig economy or will the same practices continue to predominate under the market and compliance model? Does this type of practice configuration that suppresses long-term commitment generate more value for the Gig Economy company? To this end, it is very important to consider appropriate methodological approaches that incorporate valid and reliable measures of the HR practices that constitute the different configurations manifested in the model for comparison.

Second, and in line with the recognition of multiple systems of HR practices within a single organization, will a company operating in the Gig Economy, which "employs" thousands of workers, recognize any differences among workers and implement different HR practices? This question follows the idea that HR practices for the entire workforce would not be appropriate (Lepak and Snell, 2002), hence the use of HR practices may vary concerning the job (Tsui et al., 1997). However, empirical research in this direction in the context of the Gig Economy is still limited.

Third, considering the possibility that HR practices are implemented differently for the Gig Economy workforce, gig workers might perceive or experience differences in the labor practices they are exposed to, even when they have similar skills and work under the same platform; a similar idea for people in companies in other sectors working in the same position (Liao et al., 2009). So how do workers in the Gig Economy perceive or experience these types of practices? Are there differences between what the companies that own the platforms say they apply and the perception of gig workers? To date, very little is known about how gig workers perceive and respond to the configuration of HR practices.

Fourth, if there were differences between gig workers' perceptions of the HR practices they receive, how does this perception influence their attitudes and behaviors? This question is consistent with the need to take individual attributes into account when considering internal fit in HR practice systems. As Nishii et al. (2008) demonstrate in their study, people may have different perceptions and interpretations of the same HR practices, which in turn may influence people's attitudes and behaviors. This result highlights the potential value of focusing on individual employee differences in the impact of HR systems on performance. Furthermore, as people differences have a direct influence on people's perceptions and attitudes in the workplace (Liao et al., 2009), future studies on gig workers could consider a variety of demographic or functional differences (e.g., age, gender, education level, and seniority using the intermediary platform) as other characteristics that are not visible, and underlying, such as personality or values (Jiang et al., 2012).

Finally, in line with existing research in the HR field that has examined the influence of external factors and organizational characteristics on the design of HR systems (Jiang et al., 2012), future research in the Gig Economy framework could further explore how contextual factors (e.g., organizational size, industry in which the firm operates, organizational philosophy/ culture, home countries, etc.) may impact the configuration in HRM noted in this article and, as a consequence, workforce and firm performance. For example, are market-driven and compliance-oriented HR practices equally effective across companies that use technology platforms to mediate the employment relationship, and is the outcome the same for similar companies in different countries, and is the outcome strengthened by comparing the use of these practices to companies in other industries that do not use labor brokering platforms? What is the prevailing philosophy/culture in Gig Economy companies that facilitates a configuration of practices distant from long-term engagement? Ultimately, more research is needed to explore in greater detail how context influences the internal alignment mechanisms of HR systems in the context of the Gig Economy.

text in

text in