Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Antipoda. Revista de Antropología y Arqueología

Print version ISSN 1900-5407

Antipod. Rev. Antropol. Arqueol. no.5 Bogotá July/Dec. 2007

"VISUALIZING" APARTHEID: CONTEMPORARY ART AND COLLECTIVE MEMORY DURING SOUTH AFRICA'S TRANSITION TO DEMOCRACY1

Erin Mosely2

2 Editorial Assistant at the Woodrow Wilson international Center for Scholars, Washington, D.C. She has a M.Sc. In Human Rights from the London School of Economics and a b.A. in American Studies from Northwestern University. From 2003-05 she worked at In These Times, a progressive news magazine based in Chicago. Her research focuses on local approaches to transitional justice and post-conflict reconciliation, especially those that incorporate artistic and/or cultural methods. London School of Economics Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington, D.C., EE.UU. erinmosely@gmail.com

Corrección de estilo de Wally Broderick

ABSTRACT

This article examines contemporary art work in South Africa in orderto understand its role within the larger process of transitional justice taking place in the country. How has contemporary art contributed to and/or shaped the construction of a 'collective memory' about Apartheid? How has this art interacted with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC)? The author argues that South African artists have played a significant role in the overall social transformation of the country, undertaking projects which continue to negotiate the legacies of Apartheid.

KEY WORDS

Transitional Justice, Collective Memory, South Africa, Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), Contemporary Art.

"VISUALIZANDO" EL APARTHEID: ARTE CONTEMPORÁNEO Y MEMORIA COLECTIVA DURANTE LA TRANSICIÓN A LA DEMOCRACIA EN SUDÁFRICA

RESUMEN

Este artículo examina los trabajos de arte contemporáneo en Sudáfrica para entender su rol dentro del proceso de justicia transicional que tiene lugar en este país. ¿Cómo ha contribuido y/o ha moldeado el arte contemporáneo la memoria colectiva sobre el Apartheid? A su vez, ¿cómo ha interactuado con la Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación (TRC) sudafricana? La autora expone la importancia del rol de los artistas en la transformación social de este país, con el desarrollo de proyectos que continúan negociando el legado del Apartheid.

PALABRAS CLAVE

Justicia transicional, memoria colectiva, Sudáfrica, Comisión de la Verdad y la Reconciliación (TRC), arte contemporáneo.

FECHA DE RECEPCIÓN: ABRIL DE 2007 / FECHA DE ACEPTACIÓN: SEPTIEMBRE DE 2007

INTRODUCTION

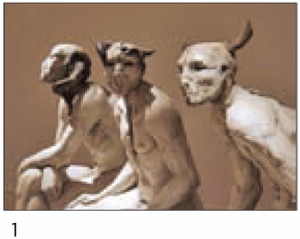

In 1989, Jane Alexander made a statement out apart -heid -a chilling, perverse and unforgettable statement in the form of three, life-size sculptures. Aptly entitled Butcher Boys, and permanently housed in the main room of the South African National Gallery, this assemblage of once-human creatures elicits a visceral sensation of fear and repulsion on the part of observers. They were men, but have transformed into demons. They are us, but they are most decidedly not us or at least not us anymore. Commenting on the larger societal context in which Apartheid flourished -an overly militarized and masculinized regime sustained by authoritarianism and the routine use of violence- Alexander, through her sculpture, is able to demonstrate the insidious ways in which the Apartheid system manipulated and corroded the humanity of its perpetrators to the point that they became brutal and monstrous semblances of their former selves.

Encountering Butcher Boys in the gallery space, which allows observers to circle around the figures and take in fully the eerie details of their diseased state -horns and snouts, knotted spines, those vacuous, soulless eyes- one cannot avoid being struck by the terrible wickedness of Apartheid. Rather than see it only as the brutality toward its victims, however, we are able to confront it on a more holistic level and comprehend the ways in which it pervaded all of South African society. Alexander's piece stands as a testament to darker days, a time in which boys became butchers -and, by extension, a time in which people were butchered- and because of this it serves an important role in the context of South Africa's transition to democracy. Provocative, frightening, and uncomfortable to witness, it functions as a powerful visual reminder of what the country is leaving behind, and, along with many other contemporary art pieces and installations that have emerged in South Africa's transitional period, contributes to a growing archive of visual culture which seeks to grapple with and make meaning out of the legacy of Apartheid.

Since 1994, most of the country's galleries and art museums have under-gone dramatic changes in order to more accurately represent the multiracial reality of South Africa's population. As a result, these cultural establishments have opened up to include a more diverse range of artists and curators, and, in keeping with the nation-building objectives of South Africa's transition to democracy, have reoriented themselves to tell an altogether different story about the past. Rather than cater to the desires of an authoritarian government -one which was intent on denying the inhumane nature of Apartheid-galleries and art museums are now attempting to forge a new understanding of South Africa's history, built on themes of acknowledgment, commemoration and reconciliation.

In the following article, Ii will examine the growing body of "transitional" artwork in South Africa in order to ascertain its role within the larger process of transitional justice taking place in the country. Using the politics3 of memory and meaning in post-conflict societies as my theoretical point of departure, I will address the following questions: How has contemporary art in South Africa contributed to and/or shaped the construction of a "collective memory" about Apartheid? How has this art interacted with the more formalized, in-stitutional mechanisms geared toward creating a shared understanding of the past such as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, TRC? in what ways have artists built on these official memory processes, and in what ways have they contested and/or re-imagined them?

I argue that artistic representations of trauma, when taken collectively, act as an insightful modality through which to understand the infinitely com-plex -and sometimes contradictory- experiences generated by conflict and post-conflict societies. Over the past ten years in South Africa, artists and cultural workers have taken a proactive role in the larger processes of democratic transition and national reconciliation, undertaking projects which continue to negotiate, in innovative ways, the various issues connected to both Apartheid and the process of overcoming it.

Such efforts have not been limited to South Africa, however. in almost every society emerging from conflict, we can see these kinds of artistic projects taking place. in terms of transitional justice discourse, then, it is imperative that we recognize the diverse ways in which people seek to reckon with events of the past, as well as the fact that "transition" might signify a more lengthy duration than we have come to expect. Such periods of change and reorientation do not simply end with the publication of an official truth commission report or with the judgment of former dictators and war criminals. On the contrary, the politics of memory continue; in fact, it is often in the wake of these moments of national closure that some of the most provocative and meaningful responses to former atrocities materialize.

COLLECTIVE MEMORIES AS PRODUCTS OF POWER: WHO DECIDES?

It will also be important to see how this messy activity of memory, this intricate crossing ofthe individual and social, has been subject, in South Africa, to particular pressures, and distortions

(Nuttall, 1998: 76).

Milan Kundera once declared: the struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting (1978: 3). While he was referring specifically to his native Prague during the fight against Soviet communism, Kundera's observation remains compelling in a much broader sense, in that it seems to resonate quite profoundly in the context of any society attempting to disentangle itself from a legacy of violence and authoritarianism. In the aftermath of systematic policies geared toward the denial and/or cover-up of state-sponsored or state-committed abuses, individual memories can function as a valuable resource -sometimes the only resource- in establishing the truth about a particular historical period. in Foucault's terms, such recollections amount to a vivid counter-memory and will ultimately play an active and defiant role in the wake of conflict, for they can be used to resist the presence of denial and force public acknowledgment4 of egregious crimes.

Because of this transformative potential, societies undergoing political transitions have come to rely heavily on memory as an indispensable tool with-in larger processes of transitional justice and reconciliation. Whether by way of war crimes trials, truth commissions, or the creation of monuments and museums -or some combination of these approaches- the public articulation of memory, specifically with regard to trauma, has come to occupy a privileged position within national efforts to deal with and make sense out of the past5.

But how do memories function during these transitional periods? While it has become increasingly commonplace to assume that societies have both a need and an obligation to engage in this kind of memory work6, it is necessary to ask: in what particular ways are individual memories assembled, even re-fashioned, in order to construct a broader collective memory about the past? Furthermore, what happens when this "messy process of memory" takes place within an official setting?

In the context of political transitions, the establishment of a "collective" or "shared" memory, which Gibson defines as a socially acceptable understanding of the meaning of the past (2004: 204), is a selective process, one which grows out of "complex... power relations that determine what is remembered -or forgotten- by whom, and for what end" (Gillis, 1994: 3). indeed, as Simon, Rosenberg and Eppert have suggested, public remembering should always be considered in terms of power and authority, for the act of remembering, in and of itself, will inevitably be tied to its own instructive purpose:

Whatever its site and social form, remembrance is an inherently pedagogical practice in that it is implicated in the formation and regulation of mean-ings, feelings, perceptions, identifications, and the imaginative projection of human limits and possibilities. indeed, to initiate a remembrance practice is to evoke a remembrance/pedagogy, an indissoluble couplet that echoes Foucault's (1980) pivotal dialexis knowledge/power (2000: 2).

According to these theorists, memory becomes necessarily bound up in whatever pedagogical imperative happens to be serving as its guide, and so essentially serves a "strategic" function in that it helps to "mobilize attachments and knowledge that serve specific social and political interests" (Eppert, 2000: 3).

In the aftermath of violent or repressive regimes, truth commissions of-ten serve as the official mechanisms through which memories circulate, and because of this they play a powerful role in the creation of a wider public meaning about former events. As Wilson explains,

The symbolic impact of [truth] commissions lies in how they codify the history of a period (...). Popular memories of an authoritarian past are multiple, fluid, indeterminate and fragmentary, so truth commissions play a vital role in fixing memory and institutionalizing a view of the past conflict (2001:16).

Biljiba et al. (2005) have made a similar claim, stating that while ostensibly concerned with fact-finding, these bodies

rarely limit themselves to factual or forensic truth. They do not simply recount, they explain. Their ultimate aim is to forge a national consensus, a shared understanding of the past designed to advance a particular vision of the nation's political future (Biljiba et al., 2005: 3).

During South Africa's transition to democracy, this was certainly the case, for the TRC operated as the prevailing institutional mode through which individual memories about Apartheid were translated. The entire process has had a demonstrable effect in shaping the overall collective understanding of South Africa's history. Which begs the question: How have the people of South Africa responded to the TRC? HOW has its "official narrative" been received?

While important in many ways, popular criticism of the TRC suggests that it resulted in an incomplete picture of the past. it might best be considered, therefore, as a platform from which issues relating to the legacy and meaning of Apartheid continue to be debated and re-worked. The TRC was only the pre-lude to the story, after all, and as Edkins has pointed out: "The story is never finished: the scripting of memory by those in power can always be challenged, and such challenges are very often found at moments and in places where the very foundations of the imagined community are laid out" (2003:18-19).

ESTABLISHING THE "TRUTH" ABOUT APARTHEID: A CRITICAL APPRAISAL OF THE TRC

Enacted into law in 1995, the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission remains one of the most high-profile examples of how a society might effectively make amends with its violent past and is often described as a paradigm case within transitional justice circles. it was also indispensable in the creation of a collective memory of South Africa's past. According to its mandate, the TRC was to assemble as complete a picture as possible of the nature, causes, and extent of gross violations of human rights committed between 1 March 1960 and 5 December 1993 (Truth and Reconciliation Commission, TRC Mandate), and as Anthony Holiday has remarked, "The TRC was thus charged, in the first instance, with awakening the new democracy's memory of its protracted birth pangs during the Apartheid era" (1998: 46).

While it has largely been considered successful in many ways -Arch Bishop Desmond Tutu, for example, who headed the Commission, wrote that the TRC would serve as a beacon for the rest of the world (Foreword, TRC Report), and this is quite right, for it has proved to be considerably influential7- the TRC also gave rise to a range of criticisms, some of them virulent, and some even fully dismissive. Most of the comments center on the Commission's perceived failure to convey a complete, and therefore meaningful, "truth" about Apartheid.

To give an example, the Human Rights violations Committee, HRVC, was only mandated to deal with four specific crimes of Apartheid -killing, torture, abduction, and severe ill treatment, or the attempt, conspiracy, incitement or command to commit these acts. Because of this, many have argued that "The TRC ultimately failed to engage with the routine discriminations that had been built into the legal and institutional infrastructure of the country. As Mamdani remarked, "injustice is no longer the injustice of Apartheid: forced removals, pass laws, broken families. instead the definition of injustice has come to be limited to those abuses within the legal framework of Apartheid: detention, torture, murder" (1996: 6).

From a gender perspective, Ross (2003) has argued that the Commission's limited rubric of violations resulted in the alienation of women -particularly black women- who were often disqualified from occupying a "victim" position and thus written out of the process altogether. Revealingly, Ross explains, women became known as "secondary witnesses" to Apartheid, for they rarely testified about their own experiences, speaking instead on behalf of their husbands, sons and fathers8. in her view, this inferior positioning was directly facilitated by the TRC, and the Report itself admitted that the Commission's language reflected a "gender bias", acknowledging that it subsequently ignored many of Apartheid's "ordinary workings" which targeted women more frequently than men (TRC, 1998,4: 282-316)9.

By effectively sidestepping the structural issues of Apartheid10, the TRC both limited the truth it was able to tell and compromised the full story of South Africa's past. On a discursive level, this has had profound implications, for the TRC process essentially legalized trauma (Edkins, 2003: 18). in other words, the subjective, personal and multilayered experiences of living during the Apartheid era were reduced to nothing more than a series of legal violations -and civil/political rights violations at that. Moon (2006) claims that this approach has dictated the very terms on which we interpret and make meaning out of Apartheid. in her words, "Prior to the ascendancy of international discourses on human rights that shaped South Africa's reconciliatory process, no one would have seen the history of South Africa as a history of 'human rights violations" (Moon, 2006: 260).

The TRC was also widely criticized for the way it promoted itself as a "reconciliation" mechanism based on confession and forgiveness. Wilson has argued, for example, that the TRC'S insistence on framing its activities in reconciliatory terms was a political decision, and that its continuous references to national healing distorted the reality of what was going on at the local level. Essentially, he says, reconciliation served as a diversion, for in the end it attempted to repackage the TRC'S controversial position on amnesty11 as a palatable, even desirable policy, and ultimately occluded those voices that were calling for a retributive justice approach. in his view, "Reconciliation was the Trojan Horse used to smuggle an unpleasant aspect of the past -that is, impunity- into the present political order, to transform political compromises into transcendental moral principles" (Wilson, 2001: 97).

In a strategic sense, the TRC "provid[ed] a template-script of what reconciliation should consist of and involve, that is, confession, testimony, forgiveness, amnesty, and so on, into which particular individuals could fit themselves as reconciled 'victims' and 'perpetrators' (Moon, 2006: 264). Another way of putting this would be to say that reconciliation, beggnning to end, functioned as the pedagogical framework" guiding South Africa's transition, one which put immense pressure on, or even pre-determined, the overall story that would be tould about the past:

... the trc did not make it possible, nor provide a language within which people could say "I am not reconciled", or "I do not forgive you", or "I want you to be punished", or "I do not confess or apologize for what I did", or "I do not recognize this process". It did not recognize non-reconciled outcomes as possibilities (Moon, 2006: 264).

It would be unfair , however,, and more importantly inaccurate, to take stokc of these critisism and come away with the view that the TRC process was a categorical failure. Truth commissions are inherently limited bodies, and should therefore never be regarded as capable of telling the whole story. as Hayner explains, they compromise only one approach to dealing with tehe past, and is it entirely plausible -probable, even- that "at the end of a comission's work, a country may well find the past still unsettled and some key questions still unresolved" (2002: 23).

We might do better, then, to situate the TRC in its appropiate context, recognizing that in addition to -or in spite of- the work it completed, it has served as a valuable springboard for the continued negotiation of issues relating to the social significance od Apartheid . Collective memories, affter all, are active construcctions, which both generate and require contetation and ultimately exist to beremade, reformulated and and re-contextualized.

CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS AND SOUTH AFRICA'S CHANGING CULTURAL TERRAIN

They had a passion for it. Throughout the 1990s artists in South Africa took on enunciating the relationship

between memory andhistory. As ifin one paroxysm ofrecollection a flood ofartistic works

-profound andprosaic- began entering the public domain

(Enwezor, 2004:33).

The contemporary art world in South Africa has served as a fertile ground for the continued negotiation of issues relating to Apartheid. Just surveying the titles of some of the exhibits that have taken place over the last decade -Fault Lines, SettingApart, Liberated Voices, Digging Deeper, Truth Veils, Facing the Past: Seeking the Future- reveals the fact that exploring the complexity of South Africa's past and engaging with its transition to democracy have been high on the priority list for both artists and curators.

Why is this, exactly? According to a press release for the exhibition, Fault Lines: Inquiries into Truth and Reconciliation (1996), "Betrayal, sadism, mourning, loss, confession, memory, reparation, longing, these are the persis tent themes of the arts (...). Through the arts we can explore who we are, and why we do what we do to one another" (cited in Marlin-Curiel, 1999: 1). What this statement suggests is that the arts or the cultural realm more broadly, may serve as a particularly appropriate forum in which to address painful histories and experiences of trauma, due to its unique capacity to navigate the dimcult subjective and emotional dimensions of such experiences.

Furthermore, the art world is often able to retain a relatively large amount of autonomy, even during political transitions, as it usually remains independent12 from national political projects -such as reconciliation or nation-building or legitimizing the post-Apartheid government13 in the case of South Africa. it simply does not have the same objectives, and therefore does not operate with the same constraints. As Hodgkin and Radstone have observed, "It is precisely the fact that [art] does not need to produce a finished narrative or a common version of the past that... makes it particularly fruitful" (2003:173)14. Coombes has made a similar statement, noting: "artists operate within a highly privileged realm that provides a certain license (...) and this sometimes enables them to work through taboos and contradictions in a relatively 'safe' space in ways that other arenas do not permit" (2003:12).

It has also been suggested that the articulation of trauma through language has inherent limits, and that alternative modes of expression are necessary, even inevitable, in the wake of conflict. Scarry, for example, has insisted that physical pain "has no referential content" (1985: 5). According to her argument, "pain does not simply resist language but actively destroys it, bringing about an immediate reversion to a state anterior to language, to the sounds and cries a human being makes before language is learned" (Scarry, 1985: 4). Edkins, too, has discussed what she calls the "logical limitation" of language in the context of trauma, stating that:

... the language we speak is part of the social order, and when that order falls apart around our ears, so does the language. What we can say no longer makes sense; what we want to say, we can't. There are no words for it. This is the dilemma survivors face. The only words they have are the words of the very political community that is the source of their suffering (2003: 8, emphasis original).

While it is true that the TRC has well demonstrated that the horrors of Apartheid [were] not unspeakable (Marlin-Curiel, 1999:13), the increasing re-sort to metaphor and other creative mechanisms in dealing with those horrors cannot be denied. The explanation for this, in addition to the particular freedom the space of art can provide, has to do with the proactive commitment of artists and their sustained dedication to these issues. Becker (1994) has written that artists often serve a "civic" function in society, especially in times of political and social upheaval, and it is in this capacity that contemporary artists in South Africa have flourished during the transitional period, continuing to undertake projects which recognize the value and necessity of looking to the past as a way to effectively move forward.

Many of South Africa's esteemed contemporary artists -such as Paul Stopforth, Penny Siopis, Sue Williamson and Gavin Younge- were deeply in-volved in the resistance to Apartheid, engaging in various forms of protest art15 and other activism. Taking note of this, one can argue that it was somewhat of a foregone conclusion that artists would remain tuned-in during Apartheid's unraveling and continue to be active during the period following its demise. indeed, many held this view. As Becker explains, in South Africa during the early 1990s it did not even prompt much discussion -it was just "assumed that all cultural workers would have a significant role in the long-awaited transition and in future decision making" (1994: XXI).

Some theorists have even suggested that artists have a responsibility in these situations -that they are in fact ethically obliged to take a participatory role during periods of social change, because of the communicative function of art (Neke, 1999: 8)16. in the context of transitional South Africa, many artists have agreed with this perspective, articulating in interviews and in other statements that they feel they must be involved, that they must create this work, to propel the transition forward by probing the important emotional and subjective layers of the past. As Penny Siopis explains:

... our very sense of the present, the very idea of being a new South African is predicated not only on a shared, politically-charged history, but also on the imperative to look back, unpick and unpack that history, to understand not only what happened (...) but also, more importantly, the psychic and affective dimension of that experience (cited in Neke, 1999: 8).

Fernando Alvim, Carlos Garaicoa and Gavin Younge, in their artists' statement for the exhibit Memorias Intimas Marcas17, have attested to a similar feeling of artistic duty, saying:

As citizens of the "new" South Africa, we cannot afford to invest in placebo cures to the past. We need to explore our consciences and our complicity with recent history, deconstructing the legacies of Apartheid. This cannot only happen "officially" as it is currently through the Truth and Reconciliation Commission; it is an invested process which involves the individual and needs to be enacted on many levels as part of the process of establishing a way forward and recognising that the future is complex, engrained and marked with the traces of the past, the resonance of process (cited in Marlin-Curiel, 1999: 1).

The dedication of artists and cultural workers and their continuous activity with regard to socio-political issues have been hugely instrumental during South Africa's transition to democracy. However, the truth of the matter is that they would never be engaging in the kind of work they are doing -or at least not making the same impact- without the profound shifts that have occurred in the country's public galleries and art museums. The changing nature of South Africa's cultural institutions has had a significant effect on contemporary art during the transition to democracy, for it has essentially opened up a range of public spaces, facilitating greater inclusion, while at the same time providing artists with conspicuous, nationally recognized spaces in which to showcase their various messages.

Many of the shifts that have taken place can be attributed to Ben Ngubane, South Africa's former Minister of Arts, Culture, Science and Technology. in 1994 he assembled the Arts and Culture Task Group, ACTAG, which then presented the government with a comprehensive White Paper on Arts, Culture and Heritage (1996). First on the list in the report's recommendations was an immediate and thorough review of all the country's national museums, in order to evaluate both their content and organizational structure and then make suggestions for how these museums could be "brought in line" with the dispen-sation (Martin, 2004: 54). According to Martin, the proposals made by ACTAG, although they have been slow in terms of implementation, have "provided excellent opportunities for transformation" (2004: 58).

These changes have been important for numerous reasons; however, they have been particularly crucial in the sense that gallery spaces themselves function as important "memory sites" -especially during periods of transition. In South Africa, though the TRC hearings were broadcast on both radio and television, and in many ways saturated the population, it has been argued that in terms of providing a meaningful forum in which the people of South Africa could engage with these painful displays of remembrance, the "mediation" of TRC hearings was simply not sufficient. As Coombes has remarked, their "televising (...) brought into sharp focus the incommensurability of the means of representation with the actual pain, suffering, and other complex emotions lived by the central protagonists of these poignant and horrifying narratives" (2003: 243). Galleries and museums, on the other hand, because of their distinctive spatial qualities, might serve as more appropriate settings in which to absorb, emote, contemplate and even mourn this kind of sensitive subject matter:

Exhibition venues allow audiences to determine individually the time they spend on the variously layered components of a shared experience, making them generally more active and activated spaces (...) [they] also allow audiences to engage in a three-dimensional spatial experience that again is individually determined and as a result is more lived than the two-dimensional surfaces of mass media (Bester, 2004: 32).

Additionally, contemporary art museums "consistently provide one of the few spaces outside academia for public intellectuals to independently engage political issues of broad public concern" (Bester, 2004: 28). This has certainly been the case in South Africa during the past twelve years. Having reoriented themselves toward an honest and active relationship with the past, cultural institutions today serve as optimal locations in which politically savvy artists can steer the transition forward by promoting important public conversations.

"VISUALIZING" APARTHEID: HOW CONTEMPORARY ART NEGOTIATES THE WORK OF THE TRC

South African art continues to play a pivotal role in interrogating a nation in transition. The public intellectual life

constituted by the nexus of museums, curators, exhibitions and artists in the 1990s, and especially those projects and

practices framed by the TRC, is evidence ofthe healthy evolution of 'political' art in South Africa and its critical role in

the public intellectual life of our emerging democracy

(Bester, 2004:25).

In terms of contemporary art making in South Africa, the TRC continues to serve as a vibrant, if not dominant, source of creative inspiration. Bester has noted, for example, that "a number of artists have made these hearings the focus of their work", and that the media, in particular, which "played a critical role in bringing the TRC to the public (....) [has provided] artists with the raw material for an extended examination of our past" (2004: 31-32). Many artists have readily borrowed from the TRC -particularly its archival documents and photographic images, as a way to further instill its content in the public consciousness. This has been especially important given the fact that it has now been over a decade since the Commission conducted its work. Minty has commented, for instance, that:

The country asa whole (...) is suffering from a severe case of amnesia no-body is racist, nobody supported Apartheid and we are all one in the rainbow nation (...). Some, however, including many artists, play their part in keeping the knowledge of the past alive, believing that to understand the past is to chart a new future (2004: 110).

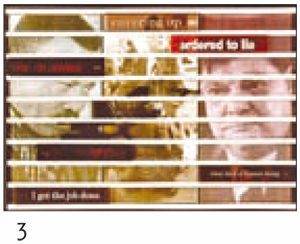

Sue Williamson has been one of the most notable artists in this regard. in describing her interest in artistically building from the TRC process, she has said: "To think we would finally hear the truth, which was beyond what could have been imagined, beyond the veil of secrecy and absolute blatant lies. I knew I would do something with it. Ii cut out newspaper articles and kept files and finally had the idea to do something case by case" (Art Throb, Art Bios).

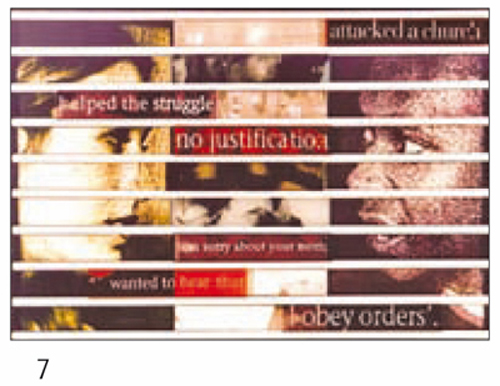

The result was Williamsons series, Truth Games (1998), which has appeared in multiple exhibits throughout South Africa and abroad. An interactive, multimedia piece, Truth Games consists of fragmented and dissected text from the TRC hearings arranged on sliding panels with photographic images that viewers can manipulate themselves (Marlin-Curiel, 1999: 5).

To explain her choice of wanting to have the audience participate in the piece, she responds:

I like to make work people feel ready to get engaged with, so they don't just walk past. lots of images are quite familiar images so I represent them so viewers are seeing something quite familiar to them in a new or different context. in many ways, I am acting as an archivist. i am presenting material in a serious way (Art Throb, Art Bios).

In addition to simply acting as an archivist, however, and facilitating the cultural entrenchment of the TRC hearings, Williamson manages to subtly question the TRC'S legitimacy. By creating a space in which observers become the "authors" of the truth -and moreover by referring to this process of truth-telling as a game- Williamson complicates the very notion of collective truth, emphasizing instead how the TRC produced multiple, and sometimes incompatible or incommensurable truths.

In Papering Over the Cracks, she similarly embarked upon a "re-presentation" of TRC materials, but this time her objective was to publicly mark the Calendon Square police station in Cape Town, which had served as a notorious center of detention and torture during the Apartheid era. By plastering text -consisting of victims' testimonies describing their experiences of torture- to the outside edifice of the police station and then taking photographic images of the scene, Williamson in effect "visually condemns" the building, inducing public recognition of its sinister history.

She has described the project as "a sort of TRC for buildings" (Art Throb, Archive), which is exactly right, for what she achieves in Papering Over the Cracks -in a conspicuous, dramatic way- is the bringing to account of a public space18. Lending a powerful visual dimension to its evidentiary findings, Williamson both interacts with and extrapolates upon the work of the TRC, ultimately expanding and redefining its reach.

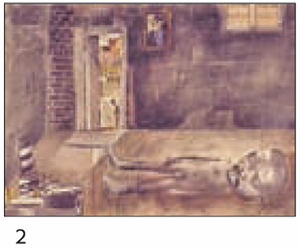

Another way that artists have sought to "visualize" the TRC'S findings is to explore "the dialectic of power and the body", particularly as it relates to the cruel and humiliating practice of torture (Enwezor, 2004:34). Here I would like to discuss Sam Nhlengethwa's It Left Him Cold, which depicts the torture of South African activist Steve Biko because it captures the essence of why artis-tic representations of trauma are so instrumental in the aftermath of violence and authoritarianism.

As Oliphant describes the piece:

Nhlengethwa presents the vulnerability of the body and its decimation through torture. The multiple perspectives are more than the mere formalities of the cut, paste, draw and paint techniques of assemblage. They are the inscriptions of torture and dismemberment. The twisted figure lies naked on the floor of what can only be described as an interrogation chamber. The torso, resting rigidly on its side, is turned to the viewer. The feet, severed from the lower parts of the legs, are twisted upward to conform to a body lying on its back. The large head is fractured and bruised. The dark interior is filled with icons of a police world. Beyond this, a universe in tumult looms (1995: 258).

It Left Him Cold invokes a powerful emotive response on the part of the viewer, but it also provides a sharp juxtaposition -and much needed alternative- to the amnesty hearings in which Biko's murderers "confessed" to his death. Because of this, the artist accomplishes two, related things: 1) he recontextualizes19 the torture and subsequent death of Steve Biko, adding emotional and psychological nuance; and 2) he encourages and enables the observer to re-spectfully mourn this tragic event.

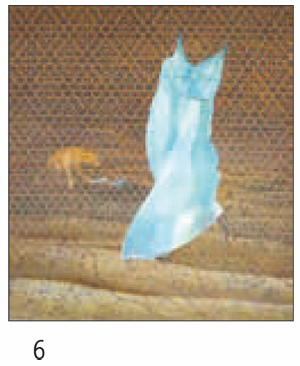

Similarly useful as a method of recontextualization has been the "invention" of protagonists who were only vaguely introduced during the TRC hearings20. Nowhere is this process of imaginative extrapolation more evident than in Judith Mason's The Blue Dress (1995), which hangs proudly in the foyer leading to the new Constitutional Court in Johannesburg21. The catalyst for Mason's piece, which consists of three, related parts, was a story that emerged in one of the TRC'S amnesty hearings about the torture, degradation, and eventual murder of a South African female activist.

Upon her arrival to the holding facility, the security personnel forced this woman to strip naked, refusing to allow her to wear any clothes for the dura-tion of her detention. At a certain point, she found a discarded blue plastic grocery sack, and proceeded to fashion it into an undergarment -it was to be her last defiant attempt at restoring her own dignity. When her body was discovered later, remnants of the blue plastic bag remained.

Mason was deeply affected by this woman's story, but felt frustrated that she had to hear about it through the callous, unremorseful voices of her killers at the amnesty hearings. So she decided to create her own version of the past, transforming the legendary blue undergarment into a series of blue dresses -one of which is actually constructed from blue plastic grocery sacks. Beside the triptych of images, she includes the following message:

Sister, a plastic bag may not be the armour of God, but you were wrestling with flesh and blood, and against powers, against the rulers of dark-ness, against spiritual wickedness in sordid places. Your weapons were your silence and a piece of rubbish. Finding that bag and weaving it until you were disinterred is such a frugal, common-sensical, house-wifely thing to do, an ordinary act (...). At some level you shamed your capturers, and they did not compound their abuse of you by stripping you a second time. Yet they killed you. We only know your story because a sniggering man remembered how brave you were. Memorials to your courage are everywhere; they blow about in the streets and drift on the tide and cling to the bushes. This dress is made from some of them (Placard, Constitu-tion Hill).

Mason's sincere and poignant commemoration of this woman's struggle -this one, brave woman who was all but silenced by history- enables a process of repersonalization which functions as a necessary step in the process of the societal transformation towards a human rights culture which the TRC aim[ed] to achieve (Marlin-Curiel, 1999: 3).

I would also argue that pieces like The Blue Dress and It Left Him Cold, which situate themselves within and yet beyond the limits of the TRC, manage to free themselves from the confining "reconciliation" framework that dominated that process, if only in that they permit a greater range of emotional reactions to the past -in this case to the often unsatisfactory amnesty "confessions".

In addition to artwork that has built from, and in a sense legitimized, the work of the TRC -albeit in imaginative and/or subtly subversive ways, there has also been a fair amount of art that has taken a more critical stance, underscor-ing the fact that certain dimensions of the past were completely excluded from the TRC process. in particular, projects focusing on structural violations such as displacement and forced removals have been among the most compelling in South Africa during the transition, bearing witness to what many consider to be Apartheid's most destructive crimes.

One example is the installation Setting Apart, which was exhibited at the Cape Town Castle in 1995. Undertaken by architect Hilton Judin, SettingApart focused on the official language of separation during the Apartheid years, and thus included archival documents such as maps, city plans and official communications:

The aim was to display and dissect the syntaxes of official Apartheid discourse, and the way its language conferred power by naming, ranking, and classifying by race, gender, and class. in particular it laid bare the repetitive exclusionary grammar that justified spatial zoning on racial lines, demonstrating the controlling practice of regulatory syntax itself (De Kok, 1998: 68-69).

In addition to archival materials, the installation incorporated a sound dimension -audio projections of interviews in which elderly black people spoke of the consequences of removal on individual and community life, on social trust, on consequent activism (De Kok, 1998: 67). The combination was forlornly powerful. in De Kok's words, The narrative of destruction, in voice and document, was a mutually soliloquized text (1998: 67). Another review-er came away with a more extreme reaction, feeling disturbed and distressed. To him, Setting Apart "[read] like a brain scan of South African power and madness (...) a narrow, mean, brutal, colonial place [with] detailed procedures through which black people were turned into objects of disgust and dread, and expelled (...) beyond the limits of the city" (cited in Neke, 1999: 8).

Either way, Setting Apart, through its exposé into the cold logic and brutal ramifications of Apartheid's spatial planning policies, functioned as a powerful narrative alongside the one being constructed by the TRC, which was just beginning its work. in thinking back to Mamdani's critique that the TRC ultimately failed to see Apartheid as a system, we can interpret Judin's installation as a necessary supplement, one that challenged the TRC and helped fill in the gaps of its broader, collective story about Apartheid.

Another example of this kind of work, and perhaps a more widely recognized one, is the District Six Public Sculpture Exhibit, which took place in Cape Town in 1997. Ninety-six artists participated in this event, whose purpose was to commemorate both the community and the landscape of District Six -an originally diverse and vibrant neighborhood that was cleared of its residents and razed to the ground after being declared a "whites only" area in 1966 (layne, 1997)22. Due to the particular history of District Six, and the fact that it represents, along with many other "lost" communities in South Africa, "Apartheid's savage attack on family life and its ruthless destruction of the fabric of functioning societies" (De Kok, 1998: 64), this sculpture exhibit garnered considerable attention in the country, especially in light of the TRC'S relative neglect of forced removals. in many artists' view, it would present a valuable opportunity to publicly call attention to, as well as emotionally and subjectively engage with, the many memories of District Six, which sadly are all that remain of this place.

Among the various outdoor sculptures that marked the occasion, there were a number of exceptional pieces. James Mader's Untitled, for example, consisted of twenty pedestals, each presenting a black and white photograph of the old District Six. The procession of images led observers in the direction of the Cape Flats, the peripheral area where most of District Six's residents were forcibly relocated. As Morphet describes the experience:

The pictures were all facing one way and to view them one had to walk down the line, the city at one's back, the Flats out in the distance ahead (...). it was clear from the clothes and the cars that the pictures of the District were all from the 70's. Passing from one to another, framed in the air, there was a sense of the past hanging over and haunting the place where we were standing (1997: 8).

Though officially only exhibited for one day, the sculptures created for this project were intended to stay on the site as long as possible, until either weather, vandalism or theft managed to break them down23. in Mader's case, this happened almost immediately, for the work was destroyed by the first eve-ning of wind, leaving bent useless metal behind (Soudien and Meyer, 1997:41). According to the artist, however, this came as an unexpected parody, and the sculpture's demise ended up further enhancing its symbolic power as a repre-sentation of the arbitrary demolition of District Six.

CONCLUSIÓN: TRUTH, MEMORY, AND THE POWER OF ART

For societies emerging from violence and authoritarianism, the issue of memory travels swiftly to the forefront of public debate. How will the conflict be remembered, people want to know; and more importantly, who gets to decide? At the root of these questions lies an awareness that the way we frame the past matters -that it's political- and that the methods by which we interrogate painful histories will have important implications for the future, both within and beyond a particular society.

Over the past two decades, truth commissions have emerged as one of the most popular mechanisms for excavating past conflicts, and, as a result they have come to wield considerable power in shaping the overall public perception of these conflicts. in the case of South Africa, the TRC played an invaluable role in providing a space and a procedure by which both "victims" and perpetrators could come together and begin the difficult work of mining their individual and collective histories. However, because this process was constrained -by political factors as well as national agendas- the omcial memory it construct-ed about the country's experience with Apartheid was inevitably compromised and thus failed to resonate with certain sectors of South Africa's population.

Given these limitations, it becomes imperative to examine other modes of memory production and filtration in South Africa, especially those whose activities directly interacted with the TRC process, such as contemporary art making. To return to Jane Alexander's Butcher Boys for a moment, it has been observed that "After nearly two decades, [the work] has lost none of its disquieting effect of threatening potentiality, as if at any moment the monsters of Apartheid's past might again waken in the dusk of reason's termination" (Enwezor, 2004: 42). Thus, in a similar and yet perhaps more enduring manner than was accomplished during the trc hearings, the sculpture functions as a stark and ominous reminder –both of the dark era of the past, but also of the social vigilance required to keep South Africa moving toward a positive and safe future.

Importantly, contemporary art in South Africa has in many ways culturally legitimized the work of the trc, despite raising subtle, yet provocative questions about its goals and methodology. In addition to this, however, many artists have felt the need to critically re-imagine the trc process, conducting work which stretches well beyond its narrow mandate in order to speak to the many untold stories of Apartheid that were often rendered invisible as a result of the Commissions limited scope.

Through their careful and sustained examination of the past, these artists have succeeded in broaching difficult but essential conversations –about the subjective nature of truth, about the largely unfulfilled expectations for justice, and about the genuine impediments to reconciliation that exist in South Africa, even today. Because of this, they have served as active agents during the transition to democracy and will likely continue to play an important role in imagining the countrys future possibilities.

1 Originally Submitted as Master's dissertation, September 1,2006.

2 Editorial Assistant at the Woodrow Wilson international Center for Scholars, Washington, d.C. She has a M.Sc. In Human Rights from the London School of Economics and a b.A. in American Studies from Northwestern University. From 2003-05 she worked at In These Times, a progressive news magazine based in Chicago. Her research focuses on local approaches to transitional justice and post-conflict reconciliation, especially those that incorporate artistic and/or cultural methods.

3 I do not mean politics in the formal, procedural sense; rather, i use it to signify the politicala realm marked by various forms of contestation, debate and struggle. See Edkins (2003).

4 Acknowledgment is what happens to knowledge when it becomes officially sanctioned and enters the public realm (Cohen, 1995:18).

5 It is important to note that remembering is not a wholly uncontroversial decision. As Hayner says, ultimate-ly, the decision to dig into the details of a difficult past must always be left to a country and its people to decide, and in some countries there may be reasonsto leave the past well alone (2001:9). Mozambique isan oft-cited example of this line of thinking.

6 Freud demonstrated that memory work is a crucial step towards working through experiences of trauma, but this concept has also been projected to the national level. According to the culturalist version of psychoanaly-sis, writes Misztal, nations -like individuals- must work through grief and trauma (2003:141). For a counter argument, see Mendeloff (2004).****

7The Sierra Leonean Truth and Reconciliation Commission, for instance, as well as the TRC in Liberia, serve as examples of commissions that have been influenced by the South African model.

8 According to Ross, although approximately equal proportions of men and women made statements, for the most part women described the suffering of men whereas men testified about their own experiences of viola-tion (2003:17). Within the hearings she attended, only 14 percent of women's testimonies concerned their own experiences of gross violation (Ross, 2003:17).

9 In the words of the Report: A large number of statistics can be produced to substantiate the fact that women were subject to more restrictions and suffered more in economic terms than did men during the Apartheid years(trc, 1998,4:288).

10 The TRC did hold a series of nine special hearings to address the institutional dimension of Apartheid; however, as Wilson has explained, this attempt was fragmented (2001:36) and in the end did little to curb the feeling that the TRC ultimately failed to see Apartheid as a system.

11While amnesty was fiercely debated in the lead up to South Africa's political transition, the National Party refused to participate in negotiations unless it was guaranteed, so that in the end, it proved impossible to move forward without it. it has nonetheless sparked a substantial body of criticism, and, according to Wilson, result-ed in vigilante-style violence in some cases, particularly among youths.

12 While independence is probably one of the most cherished values of artistic practice anywhere in the world, it is important to recognize that this independence may be limited by (....) long-term and project-specific relationships to galleries and museums (bester, 2004:28).

13 SeeWilson(2001). 14 Hodgkin and Radstone (2003) are referring to film here, and yet, i believe their comment to be true of visual culture more broadly and therefore applicable to contemporary art.

14 Hodgkin and Radstone (2003) are referring to film here, and yet, i believe their comment to be true of visual culture more broadly and therefore applicable to contemporary art***.

15 For the most comprehensive overview of protest art during the Apartheid era, see Sue Williamson, Resistance Art in South Africa, CapeTown, david Philip, 1989.

16 Neke is building from the theory proposed by Lucy Lippard (1984), which suggests that all artists, however politically naïve, are guiltier than non-artists of silence in the face of injustice (1999:8).

17 Memorias Intimas Marcas (1997) was an exhibit dealing with the untold story of South Africa's involvement in the Angolan war during the Apartheid years.

18 In an infrastructural sense, we could even interpret Williamson's piece as constituting an act of naming and shaming (Cohen, 1995) by which public buildings are marked for their complicity in the commission of crimes.

19 Recontextualization is especially relevant in the South African case, as many have argued that the TRC, due to its bureaucratic and positivist approach to data gathering, ultimately stripped experiences of their narrative context. SeeWilson (2001).

20 See Coombes (2003: 262).

21 Constitution Hill, which officially opened in March of 2004, is the new site for the Constitutional Court; it is also

home to a substantial collection of contemporary art, of which Mason’s piece is a crowning achievement.

22 I n describing the decimation of District Six, which began in 1966 and ended with the last phase of removals in 1981, De Kok has noted that "What happens in the register is chillingly logical: first the occupations of residents are deleted, so that there is no sense of economic activity at all. Then the names of residents become fewer and fewer and then, as the houses are demolished, even street names are no longer recorded. By the end it is as if nobody ever lived in District Six" (1998: 65).

23 According to Meyer, As we expected, during the course of the exhibition much of the work was vandalized, metal was taken to be resold, precast walling, corrugated iron and bricks were removed -possibly to build informal settlements- and some installations were broken. This process was interesting as it showed how differently sculpture could relate to the everyday world; it allowed the public to reuse the material as they say fit (....) but it also allowed the public to mark its own presence (... ) . Some artists expressed the view that to have their work destroyed was not a new concept considering the history of the district Six landscape, where so many people's lives and homes were destroyed (Soudien and Meyer, 1997:1).****

REFERENCES

Art Throb: Contemporary Art in South Africa, 1998-2003, The Archive, Cd-Rom. [ Links ]

Becker, Carol 1994 The Subversive Imagination: Artists, Society, and Social Responsibility, New York, Routledge [ Links ]

Bester, Rory 2004 "Spaces to Say", in Emma Bedford (ed.), A Decade of Democracy: South African Art 1994-2004, From the Permanent Collection ofIziko: South African National Gallery, Cape Town, Double Storey books. [ Links ]

Bilbija, Ksenija, et al. 2005 The Art of Truth-telling about Authoritarian Rule, Madison, WI, The University of Wisconsin Press. [ Links ]

Cohen, Stanley 1995 "State Crimes of Previous Regimes: Knowledge, Accountability, and the Policing of the Past", in Law and Social Inquiry, Vol. 20, No. 1, pp. 7-50. [ Links ]

Coombes, Annie E. 2003 History After Apartheid: Visual Culture and Public Memory in a Democratic South Africa, Durham, NC, Duke University Press. [ Links ]

De Kok, Ingrid 1998 "Cracked Heirlooms: Memory on Exhibition", in Sara Nuttall and Carli Coetzee (eds.), Negotiating the Past: The Making of Memory in South Africa, Oxford, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Edkins, Jenny 2003 Trauma and the Memory of Politics, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Enwezor, Okwui 2004 "Contemporary South African Art at the Crossroads of History", in Sophie Perryer (ed.), Personal Affects: Power and Poetics in Contemporary South African Art, Cape Town, Spier. [ Links ]

Ibson, James l. 2004 "Does Truth Lead to Reconciliation? Testing the Causal Assumptions of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Process", in American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 48, No. 2, pp. 201-217. [ Links ]

Gillis, John R. 1994 Commemorations: The Politics of National Identity, Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Hayner, Priscilla 2002 Unspeakable Truths: Facing the Challenge of Truth Commissions, New York, Routledge. [ Links ]

Hodgkin, Katherine and Susannah Radstone 2003 Contested Pasts: The Politics of Memory, London, Routledge. [ Links ]

Holiday, Anthony 1998 "Forgiving and Forgetting: The Truth and Reconciliation Commission", in Sara Nuttall and Carli Coetzee (eds.), Negotiating the Past: The Making of Memory in South Africa, Oxford, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Kundera, Milan 1978 The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, London, Penguin books. [ Links ]

Layne, Valmont 1997 "Whom it may, or may not, concern, but to whom this appeal is directed anyway", in C. Soudien and R. Meyer (eds.), The District Six Public Sculpture Project, Cape Town, The district Six Museum Foundation. [ Links ]

Mamdani, Mahmood 1996 "Reconciliation Without Justice", in South African Review of Books, Vol. 46. [ Links ]

Marlin-Curiel, Stephanie 1999 "Art in Response to the TRC", Conference Paper, me Commissioning the Past, university of the Witwatersrand. [ Links ]

Martin, Marilyn 2004 "The Horn of the National Museum's Dilemma", in Emma Bedford (ed.), A Decade of Democracy: South African Art 1994-2004, From the Permanent Collection ofIziko: South African National Gallery, Cape Town, Double Storey Books. [ Links ]

Mendeloff, David 2002 "Truth-Seeking, Truth-Telling, and Postconflict Peacebuilding: Curb the Enthusiasm?", in International Studies Review, Vol. 6, pp. 355-380. [ Links ]

Minty, Zayd 2004 "Finding the'post-black' position", in Emma bedford (ed.),A Decade of Democracy: South African Art 1994-2004, From the Permanent Collection ofIziko: South African National Gallery, Cape Town, double Storey books. [ Links ]

Misztal, Barbara 2003 Theories of Social Remembering, Maidenhead, Open University Press. [ Links ]

Moon, Claire 2006 "Narrating Political Reconciliation: Truth and Reconciliation in South Africa", in Social and Legal Studies, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 257-275. [ Links ]

Morphet, Tony 1997 "Sculpture in the Elements at district Six", in C. Soudien and R. Meyer (eds.), The District Six Public Sculpture Project, Cape Town, The district Six Museum Foundation. [ Links ]

Neke, Gael 1999 "(Re)Forming the Past: South African Art bound to Apartheid", Conference Paper, TRC Commissioning the Past, university of the Witwatersrand. [ Links ]

Nuttall, Sara 1998 "Telling 'Free' Stories? Memory and democracy in South African Autobiography since 1994", in Sara Nuttall and Carli Coetzee (eds.), Negotiating the Past: The Making of Memory in South Africa, Oxford, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Oliphant, Andries Walter 2004 "Postcolonial South Africa: Three Canvas bags on Art and Change", in Emma bedford (ed.), A Decade of Democracy: South African Art 1994-2004, From the Permanent Collection ofIziko: South African National Gallery, Cape Town, Double Storey Books. [ Links ]

Oliphant, Andries Walter 1995 "A Human Face: The death of biko and South African Art", in Seven Stories about Modern Artin Africa, New York, White Chapel Art Gallery. [ Links ]

Ross, Fiona 2003 Bearing Witness: Women and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa, London, Pluto Press. [ Links ]

Scarry, Elaine 1985 The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking ofthe World, Oxford, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Simon, Roger I., Sharon Rosenberg, and Claudia Eppert 2000 Between Hope and Despair: Pedagogy and the Representation of Historical Trauma, Lanham, MD, Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. [ Links ]

Soudien, Crain and Renate Meyer 1997 The District Six Public Sculpture Project, Cape Town, The district Six Museum Foundation. [ Links ]

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South África, TRC 1998 Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report, Cape Town, TRC. [ Links ]

Wilson, Richard A. 2001 The Politics of Truth and Reconciliation in South Africa: Legitimizing the Post-Apartheid State, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]