Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Antipoda. Revista de Antropología y Arqueología

versión impresa ISSN 1900-5407

Antipod. Rev. Antropol. Arqueol. no.17 Bogotá jul./dic. 2013

The uncertain consequences of the socialist pursuit of certainty: The case of uyghur Villagers in eastern Xinjiang, China*

Chris Hann

Ph.D., University of Cambridge, England. Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Halle, Alemania. hann@eth.mpg.de

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7440/antipoda17.2013.05

ABSTRACT:

The article is based on the author's conviction that ethnographic analysis can illuminate big issues of world history. In the framework of substantivist economic anthropology, concepts of (un) certainty and social security are applied to Chinese socialism, which has outlived its Soviet prototype. Socialism is theorized in an evolutionist perspective as the transcendence of uncertainty in modern conditions. The case study of peasants in eastern Xinjiang highlights the problems of the Uyghur minority, who are attracted to the city but lack the networks and language skills to facilitate migration, and experience discrimination in urban labor markets. China's embedded socialism is currently successful in balancing forms of integration in such a way as to reduce existential uncertainty to a minimum for the dominant Han population, both inside and beyond the village. However, Uyghurs find it more problematic to exit their villages. This has led to resentment and violent resistance in recent years, to which there is no end in sight.

KEY WORDS:

China, economic anthropology, embeddedness, Maoism, reform socialism, social security, uncertainty, Uyghurs, Xinjiang.

Las consecuencias inciertas de la búsqueda socialista por la certeza: El caso del pueblo Uyghur en Xinjiang oriental, China

RESUMEN:

Este artículo se basa en la convicción del autor de que el análisis etnográfico puede iluminar grandes temas de la historia del mundo. Teniendo como marco la antropología económica sustantivista, se emplean los conceptos de (in)certidumbre y seguridad social para examinar el socialismo chino, el cual ha sobrevivido a su prototipo soviético. La perspectiva evolucionista teoriza el socialismo como la trascendencia de la incertidumbre en condiciones modernas.

El estudio de caso de los campesinos de Xinjiang Oriental resalta los problemas de la minoría Uyghur, que es atraída a la ciudad, aunque carece de las redes y habilidades lingüísticas para facilitar la migración y es víctima de discriminación en los mercados laborales urbanos. El socialismo enraizado en China actualmente equilibra con éxito las formas de integración, de manera tal que reduce al mínimo la incertidumbre de la dominante población Han, tanto dentro de la aldea como fuera de ella. Sin embargo, los Uyghurs enfrentan más problemas para salir de sus aldeas, lo que ha generado resentimiento y resistencia violenta en años recientes, sin que haya un final a la vista.

PALABRAS CLAVE:

China, antropología económica, enraizamiento, maoísmo, socialismo de la reforma, seguridad social, incertidumbre, Uyghurs, Xinjiang.

As consequências incertas da busca socialista pela certeza: O caso do povo Uyghur en Xinjiang oriental, China

RESUMO:

Este artigo está baseado na convicção do autor de que a análise etnográfica pode iluminar grandes temas da história do mundo. No âmbito da antropologia económica substantivista, aplicam-se os conceitos de (in)certeza e segurança social ao socialismo chinês, o qual vem sobrevivendo a seu protótipo soviético. O socialismo se teoriza na perspectiva evolucionista como a transcendência da incerteza em condições modernas. O estudo de caso dos camponeses de Xinjiang oriental ressalta os problemas da minoria Uyghur, que é atraída à cidade, embora careça das redes e habilidades linguísticas para facilitar a migração e é vítima de discriminação nos mercados laborais urbanos. O socialismo enraizado na China atualmente equilibra com sucesso as formas de integração de tal maneira que reduz ao mínimo a incerteza da dominante população Han, tanto no interior da aldeia quanto fora dela. No entanto, os Uyghurs enfrentam mais problemas para sair de suas aldeias, o que gerou rancor e resistência violenta em anos recentes sem um final à vista.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE:

China; antropologia económica; enraizamento; Maoísmo; socialismo de reforma; segurança social; incerteza; Uyghurs; Xinjiang

Introduction: socialism and the taming of uncertainty

My starting point is that the dominance of the ethnographic method in twentieth-century socio-cultural anthropology has hindered the discipline's capacity to address human social evolution and world history (Hann and Hart 2011). We routinely claim that our meticulous investigations of a particular worldview or local social relations illuminate bigger questions, but it turns out to be very difficult to specify the micro-macro links; sometimes, the claims are unsupported assertions, the lip service of scholars who do not wish to be considered mere parochial folklorists. Some big questions of world history in the era in which anthropologists have been plying their trade have attracted remarkably little attention. The one that concerns me in this paper is Marxist-Leninist-Maoist socialism. Long after the end of the Cold War, it is the continued topicality of socialism that makes it so problematic for us, including those of us who have experienced it in more democratic, "electoral" variants (Goody 2003). Anthropological theories and methods were formerly designed for application to remote peoples and more recently to marginalized people "at home." It is not easy to address beliefs and practices that still polarize political opinions, not only in the communities under investigation but also inside our own scholarly communities. In spite of the disrepute into which they fell, above all as a result of the Soviet experience, socialist ideals remain arguably the most powerful alternative we have to neoliberal capitalism. However, few anthropologists have illuminated these alternatives theoretically, and even fewer have done so on the basis of ethnographic data, the main distinguishing feature of their discipline in the last century. That is the goal of this paper, even though it concludes by leaving further questions unanswered.

There are many ways to theorize socialism. Most social science approaches emphasize continuities with the European Enlightenment. Socialists critique private property, the volatility of capitalist markets, and the alienation, exploitation, and class-based inequalities that result from these forms of economy. They propose correcting these inequalities on the basis of rational interventions to restore equity while maintaining and even improving the efficiency of new, industrial productive systems. For anthropologists, the element of rational design opens up connections to evolutionist theories. Socialism exemplifies human aspirations to do better than the natural, spontaneous processes of the market by intervening with some sort of plan. The theoreticians of market society regard this as a fatal conceit. In the tradition of the later Adam Smith, they believe that the invisible hand of the market, not central planning, will deliver the optimum outcomes. There is an affinity here to biological mechanisms of natural selection, in which design emerges not from a master plan but through the actions of myriad actors (though whether the prime level of selection is the gene, the core genome, the organism, or some larger collectivity is still disputed). The principal theoretician of this evolutionist approach, legitimating a pro-market political economy with reference to fundamental liberties, is Friedrich Hayek. The principal critic of market society is Karl Polanyi, who, without quite embracing a socialist alternative (it was not easy to do so in North America in the years of the Cold War), insisted that freedom in a complex industrial society must be based on democratic government rather than allegedly self-regulating markets. These Central Europeans published classical formulations of their contrasting paradigms toward the end of the Second World War (Hayek 1943; Polanyi 1944).

In the second decade of the twenty-first century, following the financial crisis that erupted in 2008, the scientific and ideological stakes appear remarkably similar. Can the history of the last seven decades help us to resolve the great debate? We now know a great deal more about Stalinist repression and the gulag camps than Hayek and Polanyi could have known in the early 1940s. We know about catastrophic famines in early 1930s Ukraine, a tragedy repeated some three decades later in the course of Mao Zedong's "Great Leap Forward" (launched in 1958). We know about the enormous human and ecological costs of socialist interventions, such as the Virgin Lands program in the U.S.S.R. and the Three Gorges Project in China. Desertification and pollution have been endemic to the breakneck growth of these large socialist societies. All this suggests that Hayek was right. Centrally planned economies may set out to improve human welfare and tame the vagaries of nature, but in practice, they have achieved only the opposite. The fact that the majority of citizens rejected Soviet-style socialism as soon as they had a chance to do so appears to confirm this interpretation.

However, alternative interpretations are also possible. Much changed in the last decades of the Soviet Union and in China following the death of Mao Zedong. No one experienced hunger any longer. Many developmental indicators reveal favorable performance in comparison with the capitalist world in domains such as health care and education. I argue that these mature socialist societies provide support for the Polanyi position. The U.S.S.R. of the Brezhnev years did not have a particularly successful economy, and consumers had to find ingenious ways to cope with shortages of consumer goods, yet the overwhelming majority of citizens enjoyed a degree of existential security and conditions of relative equality never experienced previously. As Alexei Yurchak has shown, they could not imagine living in any other social system and were completely taken by surprise when the U.S.S.R. imploded (Yurchak 2006).

The path of China, the main focus in this paper, has been different. It remains socialist, but since 1979 it has steadily expanded the domain of the market. I argue that the main effect of these policies was to stabilize socio-economic relations such that, as in the U.S.S.R. earlier, historically unprecedented conditions of security prevailed for the vast majority of the population. This was most obvious in the countryside, even though peasants did not partake to the same degree as city dwellers in the welfare institutions of the state. Egalitarian land distribution and the interventions of an active local state combined to banish the threat of absolute poverty and hunger. However, since the early 1980s, hundreds of millions of peasants, the "floating population" have sought work in China's booming cities. For some, migration may be the only option, but others evidently prefer the often harsh conditions of unskilled urban employment to those of small-scale, subsistence-oriented agriculture. This is the background of my case study. Some argue that the principle of the market has become so powerful as to constitute a variant of "neoliberalism with Chinese characteristics" (Harvey 2005). I find this to be too simple and offer instead a concept of "embedded socialism" (Hann 2009). China's relative immunity to the ongoing global economic crisis shows the success of power holders in retaining control over the trajectory of their economy.

Within China, I concentrate on the Uyghurs, a minority in the Northwest. The peasants of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) have not flocked to work in the prosperous provinces of southern and eastern China. On the contrary, large numbers of Han peasants have migrated westward into Xinjiang as an alternative to the coastal provinces. Their language gives them an advantage over local Uyghur peasants in the labor market. Moreover, there is very significant variation within the sub-regions of Xinjiang and even within townships and villages. It follows that my ethnographic data from one village in the oasis of Hami cannot be regarded as representative of the XUAR, let alone the People's Republic of China (PRC) as a whole. I shall nonetheless argue that my detailed materials shed light on the very large issue addressed above, namely socialism as a world-historical force to improve human lives by providing basic social security in the framework of what Polanyi (1944, 1968) termed an embedded economy. Another way to phrase this is to say that socialism set out to combat the major sources of uncertainty affecting human lives, including individual and collective life chances. Before turning to the ethnographic setting, in the following section, I consider some of the influential approaches to uncertainty in the literature of economic anthropology, where it is closely linked to the concept of risk and opens up to more comprehensive investigations of social reproduction.1

Uncertainty and social security in anthropology

Risk and uncertainty, like many other topics and virtually everything pertaining to the economy, are approached in radically different ways by different kinds of anthropologists. Some consider it the task of the social sciences to formulate universal laws in the manner of physics, but even economists have not been notably successful in this respect. Scholars in fields such as evolutionary psychology hazard general statements about human nature over millennia on the basis of what anthropologists have documented in recent fieldwork in societies with "simple" technologies. Such inferences are highly dubious. In any case, socio-cultural anthropologists have greatly expanded their field of study. For most specialists in economic anthropology, an ethnographic investigation of the London Stock Exchange is nowadays just as legitimate a subject as the survival strategies of remote groups of hunter-gatherers in the Kalahari. This sub-field has long lacked theoretical coherence. At one extreme, those who operate within "formalist" or "decision-taking" paradigms see no need to modify the axioms of neoclassical economics in studying the diversity of non-market, non-industrialized economies. In other words, the toolkit of the modern economist is, in their view, truly universal. Such scholars may be sympathetic to evolutionist approaches in accounting for varying surface manifestations of economic behavior. Alternatively, they may simply attribute such diversity to a black box called "culture." At the other end of the spectrum are those culturally oriented colleagues who approach every economy as deeply, not just superficially unique, best investigated not on the basis of a universalist psychology but in terms of the "local models" held by its agents. Between these extremes, those in the "substantivist" school established by Karl Polanyi reject the universalism of the formalists but nonetheless attempt to develop general types. Polanyi himself relied throughout his career on the concept of "forms of integration" (his main examples were reciprocity and redistribution; for a mature synthesis, see Polanyi 1977, 35-43). The substantivists investigate the "embeddedness" of the economy in wider social contexts, asking questions similar to those posed by economic and historical sociologists and social and economic historians (see Hann and Hart 2011, 56-63).

These incommensurate paradigms have colored analyses of the significance of uncertainty and risk for economic behavior, and for social organization more generally. Even for so-called hunter-gatherers (those formerly known as Naturvölker), a scientific consensus is lacking. There is overwhelming evidence to show that, in regions where food supplies or climatic variation pose obvious threats, human communities respond by evolving institutions to cope with these risks. Rules of egalitarian sharing are one such institution. Marriage rules that require mates to be sought outside one's own group can be viewed as a mechanism to create wider social networks such that, no matter how bad the crisis at home, help may be provided by affines occupying a different ecological niche. With the development of storage facilities, a chief typically regulates redistribution. Many socio-cultural practices can be related to specific economic rationalities; generally, the greater the risk is that a resource important to sustaining human life might become unavailable, the greater the egalitarian pressure will be to share it (Cashdan 1990). The benefits, for example in terms of better nutrition, accrue to the group as a whole. The issue of group selection remains controversial. In any case, the maximization of adaptive fitness is a different principle from the economist's axiom of individual utility maximization, though some research into "optimal foraging strategies" has sought to combine these perspectives. However, there is also evidence from economic anthropology that points in another direction by challenging the assumption, still widespread among economists, that earlier forms of society were necessarily more vulnerable to risk and uncertainty. The substantivist Marshall Sahlins (1972) pointed out that many hunter-gatherers need spend only modest amounts of time working to obtain all they need to satisfy their limited wants; did these people perhaps lack our preoccupation with uncertainty?

In the second half of the twentieth century, anthropologists widened their scope to engage with economies known as "peasant" The definitions were often imprecise, but peasants were held to differ from farmers in owning little capital, consuming a significant proportion of their output, and being poorly integrated into national and international markets. Peasants were usually locked into wider structures of power and often harshly exploited. Like hunter-gatherers, they had to develop institutions to deal with risk and uncertainty, including unpredictable market prices for their cash crops. In his influential study of Southeast Asian peasants, James Scott (1976) adapted historian E. P. Thompson's concept of the "moral economy," originally applied to the urban crowd in eighteenth-century England. Moral economies tend to be conservative in the sense that their agents will not take risks that might jeopardize the subsistence of their families, and they will sanction the behavior of those who flout this norm. This principle of "safety first" had affinities with influential strands in the cultural anthropology of the "modernization" era. Clifford Geertz (1963) found that "shared poverty" was one way in which Javanese peasants coped with increased population pressure, though this strategy hindered them from proceeding down the road of differentiation and development. George Foster's (1965) theory of "limited good" based on Mexican examples, was another influential explanatory model of the peasant economy. Although none of these scholars worked exclusively in economic anthropology, all had an affinity with Polanyi's substantivist school.

The "formalists" criticized the substantivists for exaggerating the extent of risk-averse behavior and the egalitarian value consensus that allegedly underpinned it. Scholars such as Sutti Ortiz (1973) emphasized the way in which peasant farmers, in her case in Colombia, coped as individual choice-makers with the challenges presented by their uncertain environment, including the uncertainties of market prices, yet Scott's most basic contentions concerning the importance of a "subsistence ethic" were not refuted. In a period in which the prices of food staples are rising sharply on world stock exchanges, this notion has renewed pertinence in many parts of what we now call the "Global South." Indeed, in the age of neoliberal markets and the "risk society," it should not be a surprise that, at least on campuses and in certain think tanks, notions of a moral economy and the ethical foundations of markets are again being widely debated (see Hart, Laville and Cattani, 2010). Uncertainty concerning employment, pensions, and living standards has risen in the most advanced capitalist economies of Europe and North America, and it also characterizes the rapidly growing economies of other continents. Jane Guyer (2009), following Karl Polanyi, has proposed that risk be added to the substantivists' list of "fictitious commodities"

As indicated in this brief review, most anthropologists in this field do not confine themselves to the study of economic adaptations but extend their interest to all of the social institutions through which human communities cope with uncertainty and risk-taking. First in line are the institutions of kinship, fundamental in the provision of help across all human societies. It is well documented that, as evolutionists would expect, kinship generally means biological relatedness. However, while gatherers tend to work individually and to share food with a small group of relatives, hunters typically supply meat to all the members of a camp. Among the !Kung San of the Kalahari, personalized reciprocal links are systematically cultivated so that individuals have additional sources on which to draw beyond their relatives and affines (Lee 1979). Kinship remains of fundamental importance in the provision of social security in contemporary European societies, although there is considerable variation between north and south and between rural and urban sectors (see Heady 2010).

Another source of support may come from the beliefs and practices we generally gloss with the term "religion." In early human societies, taboos and rituals can be understood as mechanisms to reduce risk and thereby increase social cohesion and evolutionary fitness. With the emergence of religious specialists and churches, doctrines such as the Christian call to provide disinterested support to one's neighbor can underpin substantial material transfers to those in need. Cosmological beliefs provide reassurance and solace to the individual, but they also sustain collective identities and ways of life. Nurit Bird-David (1990) showed that the Nayaka forest dwellers in India have a "local model" that emphasizes the high degree of food security provided by their "giving environment." This sense of primeval security made it very difficult to discipline them for new lives as farmers or factory workers in a modern Indian society full of uncertainty for most of its members, but not for the Nayaka, to the extent that they retained the time orientation and preferences of their forest past.

Finally, almost everywhere in the contemporary world, the state plays a vital role in the provision of the citizens' well-being. The institutions of kinship and religion are not entirely displaced, but European states (and within Europe those of Scandinavia) have led the way in developing systems of social insurance and welfare provision that extend "from the cradle to the grave." A comprehensive approach must therefore integrate state provision into the evolved beliefs and practices of the domestic and religious domains. Legal anthropologists have pioneered the conceptualization of this field under the general term "social security" (von Benda-Beckmann and von Benda-Beckmann 1994).

China, Xinjiang, and Uyghurs in Hami/Qumul

Having outlined my big question and noted some of the anthropological literature pertinent to uncertainty, let me now turn to some data from China. The world's most populous state is now in its seventh decade of socialist rule. In terms of science, technology, and proto-industrial initiatives, imperial China vied with the West over millennia. However, the West obtained a decisive advantage through the Industrial Revolution and drove this home with its colonial expansion in the nineteenth century. China was not formally colonized, but the entire society was radically undermined. Political instability, capitalist penetration, and demographic growth accentuated economic uncertainties for a population that remained predominantly rural. New systems of credit and ownership destroyed the small-scale rural industries that had evolved over centuries. As a result, malnutrition, and famine were endemic. The condition of the Chinese peasantry in the pre-socialist era was one of extreme vulnerability, famously likened by Tawney (1932, 77) to a "man standing permanently up to the neck in water, so that even a ripple is sufficient to drown him." A close-up anthropological account of how poverty and inequality played out in one village in the lower Yangtze valley was provided by Fei Xiao-tong in his doctoral thesis, prepared in London under the supervision of Bronislaw Malinowski (Fei 1939).

The micro data I present in a chronological outline below derive from a recent project at the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology. Space does not allow a comprehensive summary, but it is clear that kinship, religion, and the state all play a significant role in enabling villagers in eastern Xinjiang to deal with uncertainty. Each of these components has undergone change in the course of history, as has the manner of their interaction, especially in the turbulent history of the last century. An Uyghur village in Xinjiang is evidently a setting very different from Fei's case study in the Yangtze delta, but I shall emphasize themes that I consider valid across the entire country.2

The Uyghurs are a Turkic-speaking people who number around nine million in the XUAR. Distantly related to inner Asian nomadic tribes, they can look back on more than a millennium as sedentary farmers in the fertile oases of the Tarim Basin. Conversion to Islam was a slow process that began in the west in Kashgar in the eleventh century and was completed in the east in Qumul only in the seventeenth. The Uyghurs have differentiated themselves from their pastoral neighbors, Kazakh and Kyrgyz. None of these identities congealed in its present form until the twentieth century, when they were institutionalized through the impact of socialist minority policies. Although artisans and traders flourished in the celebrated oases of the Silk Road, the economy of Xinjiang remained predominantly agricultural and pastoral after the region was conquered by the Qing in the middle of the eighteenth century. Social divisions were marked, even within the farming population. The major settlements received water from surrounding mountains and were not vulnerable to rainfall variation. However, when Kashgar was hit by an earthquake in the late nineteenth century, local power holders responded by helping those in need. Public almshouses and granaries were grafted on to the practices of Islamic charity, but the fundamental safety net for the vast majority of the population was provided by the family (Bellér-Hann 2008, 159; Bellér-Hann (forthcoming)).

In the pre-socialist period, the Uyghurs formed more than three quarters of the population of the XUAR. Nowadays, they constitute about 45%, while Han Chinese make up almost 40%. The remaining 15% is made up of numerous smaller minorities, among whom the Turkic-speaking Kazakhs and Mandarin-speaking Hui (Chinese Muslims) are the most numerous.3 There is considerable tension between the two major nationalities, whose socio-economic profiles differ greatly. According to the precepts of the minority policy, reaffirmed in recent years in official rhetoric promoting the "harmonious society" the rights of minorities are generously safeguarded. These policies have not been implemented consistently, and preferential policies have been curtailed following the intensification of market-oriented reforms after the introduction of the Develop the West campaign in 2000. As a result, Uyghurs are nowadays hugely under-represented not only in the state sector but in the market for skilled labor in general (Fisher (forthcoming); cf. Hann 2011). Most Han in the XUAR live and work in urban blocks, identical to modern buildings all over the PRC, and in the unique institutions of the bingtuan.4 The rural periphery is populated overwhelmingly by Uyghur peasant farmers (Uyghur: dehqanlar). Population densities are heaviest in the south. Young people with no prospects of finding work in their prefecture migrate to the regional capital Urumchi and other Han-dominated towns of the north, where jobs are more readily available, but they cannot compete equally with Han immigrants and have difficulty establishing formal urban residence.

In the eastern prefecture of Qumul, which borders on the province of Gansu, Uyghur are nowadays heavily outnumbered by Han in the city, though here too, most rural districts remain solidly Uyghur. To the north of the Tian Shan Mountains, there is a Kazakh Autonomous County, but rates of Uyghur-Kazakh intermarriage are low (marriages with Han are even more rare). Qumul has a successful economy, and it has not experienced significant violence in recent decades, which is why we received permission to live in Uyghur villages and to carry out fieldwork without supervision. Most of this time was spent in a settlement which, though nowadays classified as rural and inhabited mainly by dehqanlar, had constituted the heart of the old Uyghur city in the pre-socialist era. In this paper, however, I focus on changing patterns of social security among the peasants of the upland village of Qizilyar in the Tian Shan township, 55 km to the north.5

According to local tradition, Uyghurs (who did not yet call themselves by this name) migrated from the adjacent oasis to establish the community of Qizilyar in the early nineteenth century. Agriculture is enabled by river water, which flows from high glaciers (over 4000 m). This supply is secure, but irrigation systems are essential and annual rainfall does have an impact on the quality of pasture. In Qizilyar and adjacent settlements at an elevation of around 1500 m, it is possible to grow wheat. Higher up in the valley, only barley and oats can be cultivated. Due to poor soil, yields in the mountains are much lower than in the fertile villages of the oasis. This is compensated for by transhumance. Traditionally, some members of at least some households accompanied the animals (mostly sheep and goats but also cattle, horses, and camels) to high pastures in the summer and looked after them at intermediate locations in the spring and autumn. Presumably, the original migrations of the nineteenth century were induced by pressure on resources in the oases, but it is difficult to reconstruct the history. The pioneers in the mountains remained subjects of the ruler (Wang) of Qumul, whose Muslim dynasty had come to power in the late seventeenth century and held on to it by means of a close alliance with the Qing Emperor in Beijing. Yet the early twentieth century witnessed violent rebellions in the mountains against the tax demands of the Wang.6

We do not know much about the moral economy of upland villages in the pre-socialist era. Certainly, there were inequalities between households, and these were only slightly mitigated by the norms of Islamic charitable redistribution (öshrä-zakat). It seems likely that inequalities existed within extended families but that these close relatives were the first source of help in an emergency, i.e., if subsistence was threatened. This could happen through losing a harvest due to storm damage, but it was doubtless exceptional, and a household was in danger only if it lost its animal stock at the same time (e.g., through disease). Grain was produced for subsistence, not the market. Animals, which formed the household's principal reserve and security in this harsh environment, could be sold for cash as well as to pay taxes. Overall, these transhumant populations in the hills were probably no more vulnerable to subsistence threats than the older settlements of the oasis, where the peasant economy was less diverse but the climate was more predictable and the society more stratified.

We know even less about the worldview of the pre-socialist dehqan-lar. The uncertainties of the profane world were, to some extent, balanced by certainties in the form of firm beliefs in the sacred book. However, peasant rebellions against their Islamic rulers suggest that uncertainties may have been growing in this realm, too. Uyghur ethnographers have shown that the rural economy of Uyghur peasants in the pre-socialist era was still suffused with rituals invoking supernatural agency (Häbibulla 1993). The prayers spoken at the completion of the harvest resemble popular practices in other parts of the Muslim world. Some rituals integrated pre-Islamic beliefs and practices, such as weather magic, to allay existential fears in a harsh and vulnerable environment. In the central villages of the Qumul oasis, it was customary until the late 1950s to perform a spring fertility ritual at a nearby stream (Hann 2012). The performance of rainmaking rituals, somewhat later in the season, adjacent to a stream or spring, was a related practice in mountain villages such as Qizilyar (Bellér-Hann and Hann (forthcoming)).

Maoism

The Maoist decades destroyed the integrity of the traditional peasant economy: in the mountains, in the oasis of Qumul, and all over the PRC. The support of the rural population was essential in the military struggle that brought the Communist Party to power, but it was not long before the new power holders moved beyond egalitarian land distribution to emulate the collectivist mechanisms pioneered in the U.S.S.R. As elsewhere, the villagers of Qizilyar were at first encouraged to join collective farms voluntarily, while former "rich peasants" were prevented from joining. With the Great Leap Forward (1958), all dehqanlar were drawn into the People's Commune, within which brigades and production teams constituted the effective economic units. These collectives, the rural equivalents of the new urban work-unit, were supposed to provide all citizens with protection against the uncertainties of nature and markets in the new planned economy (Parish and White 1978). However, Qizilyar villagers have almost uniformly negative recollections of this era, especially of the years during which cooking at home was prohibited and all food centrally rationed. They experienced malnutrition in the 1960s, but the peasants of Qumul and Xinjiang in general were spared the massive famine and deaths that afflicted many other parts of China. Local protests in these upland communities were quickly repressed. Mosques fell into abeyance during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) and some were destroyed, including that of Qizilyar. Some practices persisted clandestinely, but the old principles of charitable redistribution could not be implemented since households no longer had significant resources at their disposal. Collective management of both arable lands and pastures was highly inefficient. As a result, communities were plunged into the Maoist variant of Geertzian "shared poverty"

Nowadays, it is permissible to speak critically of the errors and abuses of the repressive era, which persisted until the death of Chairman Mao in 1976, yet Communist Party members and even some other peasants who did not join the Party and held no position of responsibility in the Maoist hierarchy also point to positive accomplishments. Qizilyar and its neighbors in Tian Shan township benefited from investments in a new irrigation network. Communication routes to the oasis center were improved, allowing swift access to hospitals for the first time. People still speak with respect of the ideals of this era: to eliminate structural inequalities and free the population from the vagaries of the uncertain mountain environment. However, they are scathing when they recall ambitious projects of social engineering, such as terracing hillsides and the construction of new roads across the mountains, most of which were washed away in the first major storms of the winter. Their labor power was exploited in senseless, sometimes cruel ways. Overall, the political uncertainties of the Maoist era brought more turmoil and hardship than the uncertainties of the natural environment. For dehqanlar, the political contingencies were harder to calculate than the optimal timing of agricultural tasks. Fertility and rainmaking rituals were prohibited as "superstitious feudal customs." Communities such as Qizilyar thus experienced a dramatic "disenchantment" during the early socialist decadesunless one considers the charismatic leadership of Mao to be a new form of magic (images of Chairman Mao himself were incorporated into practices of ancestor worship in many Han regions, but this did not happen in Muslim Xinjiang).

The reform era

The reforms (usually known as the "household responsibility system") that began in Beijing in 1979 reached Xinjiang a few years later (see Starr 2004). The devolution of production tasks back to the household was universally welcomed. Plots were allocated on a strictly egalitarian basis according to the number of persons to be fed. They were held with long-term leases and not privately owned. In Qizilyar, the allocation is regularly adjusted by the Village Committee according to needs.7 Seed, fertilizer and water supplies are all guaranteed by the local state through township cadres and the Village Committee. Households are responsible for sowing and irrigating their land, but in practice, they have little scope for autonomous decision-making. In theory, they can choose to plant other crops for cash. In practice, virtually all inhabitants of Qizilyar use the greater part of their allocation to produce wheat, most of which they consume themselves. As a result, no one has gone short of nan in recent years. Small surpluses of wheat or flour are either sold or sent to urban relatives. The local economy remains highly self-sufficient. It is acknowledged that this food security owes much to the egalitarian and solicitous measures of the reform socialist state.

At the local level, the state is continuously active in raising yields by introducing new seeds for staples and encouraging the cultivation of supplementary crops (beans and maize in recent years), for which the expert advice of agronomists is enlisted. These initiatives are welcomed by Qizilyar peasants.8 There is a nominal obligation to perform labor service for the community (eight days annually), but this is not strictly enforced. Taxes have been reduced to nominal levels; the state certainly spends more on maintaining the irrigation infrastructure than it receives in revenue through the water tax.9 The state has also made funds and expertise available to assist in a scheme for establishing orchards on newly irrigated land. The opportunity to earn a little money without jeopardizing subsistence has proved attractive to some, though others remain doubtful that such schemes are worth the investment of their labor.

The most ambitious scheme of the local state was the "return migration" of twenty households to the oasis lowlands, where they benefit from modern irrigation in a zone that was previously desert. Young families were given priority in the allocation of comfortable brick houses, which enjoy not only electricity (also available via the XUAR grid in Qizilyar) but also piped water. They were allowed to retain their plots in Qizilyar for subsistence production, which enabled them to devote their land and energies in the new settlement to cash crops. The scheme proved successful, though the settlements are 70 kms apart and coordination of economic activities is not straightforward. The main cash crop is cotton, which is popular in spite of its heavy labor demands and the fact that returns nowadays depend heavily on world prices, which peasants in Xinjiang have no way of predicting.

For households which did not benefit from the relocation scheme, it is difficult to obtain cash through agricultural activities. Many young men find seasonal work in bingtuan and private farms harvesting grapes and cotton (Hann 2009). The most significant opportunity to accumulate wealth in the mountains is in the livestock sector, where the state has, in effect, stepped aside in recent years. Local officials claim that they supervise complex arrangements to regulate which villages have access to which distant pastures at different periods of the year; in practice, animal migrations proceed according to customary practices dating back to the pre-socialist era. In the most common arrangement, the owner pays a daily fee per animal to the shepherd, but the full risk remains with the former. Many families have increased their holdings in recent decades, and there is general agreement that the high pastures have deteriorated significantly due to over-grazing. So far, however, the state has not intervened. The principal constraint on herd size, as in the past, is the household's ability to provide winter feed, but it is nowadays possible, if one has the money, to purchase fodder in the city to supplement that produced on local meadows (which are subject to the same principle of egalitarian distribution as arable land). A few families have built up large herds and negotiated special grazing rights in distant pastures with local state officials. These families continue to farm their subsistence plots and to participate in the moral economy of the community, just like those in the new settlement on the plain, even if they are no longer fulltime residents of Qizilyar.

The state has been active in multiple domains throughout the reform decades to reduce existential risks for all citizens of the Tian Shan township. It has built a large new school at a central location, from which numerous Qizi-lyar children have proceeded to higher education and found jobs as cadres and teachers. A few have pursued impressive careers in Urumchi and elsewhere on the basis of their diplomas. Until the late 1990s, a college degree guaranteed lifetime employment in the state sector. That this is no longer the case is a source of deep resentment to urban Uyghurs (as it is to Han), but it has little impact on the demand for education in upland townships. The major change to affect Qizilyar in recent years has been the transfer of children in the senior high school grades to board in the oasis center, where teaching is conducted almost entirely in Mandarin. While parents are generally enthusiastic about measures which they hope will improve career chances, they grumble about dormitory conditions and their children's extended absence from home; some are critical of the "assimilationist" language policy (Hann 2013: 204).

The state has also built a large medical center in the township. It is reckoned to be poorly staffed and equipped in comparison with hospitals in the city and was definitely underutilized at the time of our fieldwork. Health officials encourage all villagers to contribute to an insurance scheme which, for a modest annual payment, allows them to benefit from urban facilities at discounted rates. In Qizilyar, almost everyone subscribes to this form of health insurance. The costs of major surgery are still an enormous burden. Families are then forced to borrow money, usually from relatives. The system is less egalitarian than it was under Maoism, but it provides a higher standard of care. Apart from motor policies (there are many motor bikes in Qizilyar), this health insurance is the only form of insurance villagers know. However, in the event of a natural catastrophe, such as the severe flooding that affected the valley in summer 2007, those who suffer can be confident that the state will intervene promptly (in this case by building them a new homethough since the new houses were built to a standard Han model by mobile Han brigades, they were criticized for being culturally inappropriate).

The communitarian dimension of Qizilyar's moral economy in the years 2006-9 was vividly displayed in wedding rituals, for which it was still customary (as it was for funerals) to invite the entire community. Women worked together for days beforehand to prepare the hospitality. The payments associated with marriage have become a major financial burden since the 1980s. Mosque communities have revived their activities over the same period. Even Communist Party members attend the major Islamic festivals, which the state nowadays classifies as national holidays for the Uyghur minority. Party members also participate surreptitiously in household rituals to remember deceased ancestors. People say that having control over household production allows them to provide the hospitality that accompanies these rituals and observe öshrä-zakat as they did in the past.

However, transfers from the local state are probably more significant nowadays than religiously motivated donations. These transfers often take the form of payments in kind (flour, oil, rice, etc.), sometimes delivered at the Islamic feasts and explained with the rhetoric of the "five guarantees," a social support baseline still acknowledged by the post-Mao state.10 One elderly widower, though he still had close kin in the village, was recently admitted to a state home (sanatorium) in the city. It was apparently the first time that this had happened, but it did not generate critical comment; the old man himself spoke well of the institution when returning to visit his son. More commonly, state officials or members of the Village Committee will put informal pressure on kin to initiate private action to support a family member in need. For example, an elderly peasant incapable of producing his own grain supply may sharecrop his land with a neighbor; if the neighbor has no need of more wheat, cultivation might be switched to beans, with either a cash sum (half of the proceeds) or an equivalent in flour being paid to the infirm rights-holder. One old man in Qizilyar regularly received gifts of food from the households of his neighborhood; this did attract critical comment, since his daughter was a township cadre; however, if relatives fail to carry out their duty, strangers may offer help because it is virtuous to help a poor old man and they can be certain that Allah will reward them.

Recourse to the rhetoric of Islamic morality and the vigorous revival of both household-based and collective rituals should not be taken to indicate that the changes that have taken place in Qizilyar since the 1980s have reinstated the institutions and cultural notions of the pre-1949 era. Here, as throughout rural China, the successful elimination of the threat of hunger and malnutrition has been accompanied by novel forms of individualism and consumer-oriented behavior (cf. Yan 2009). However, these sociological trends are attenuated in villages such as Qizilyar by a number of factors: not just physical remoteness and the patriarchal nature of Islam but the cultural barriers that inhibit Uyghur dehqanlar from seeking urban employment even in their local oasis center, let alone in the XUAR capital Urumchi, or the growth centers of the east that have attracted so many millions of Han peasant migrants. In Tian Shan township, the 1980s also brought a modest revival of traditional rainmaking rituals. In Qizilyar, they soon fell into abeyance, but they were performed in 2007 at another community higher up the valley, and rain followed the next day. When reporting these events to me, even older villagers smiled. They did not seriously believe in the efficaciousness of the ritual. If it has any future, it will be as a form of folklore heritage to attract tourist spectators. The villagers themselves will seek remedies to the problems of water shortage, pasture degradation, and uncertainty in general, not through appeals to supernatural agency but in the form of better management by a rational but caring local state, which, as I have shown in this section, is already active on their behalf in so many domains. The disenchantment brutally imposed during the Maoist period has been softened since the 1980s, but it cannot be reversed.

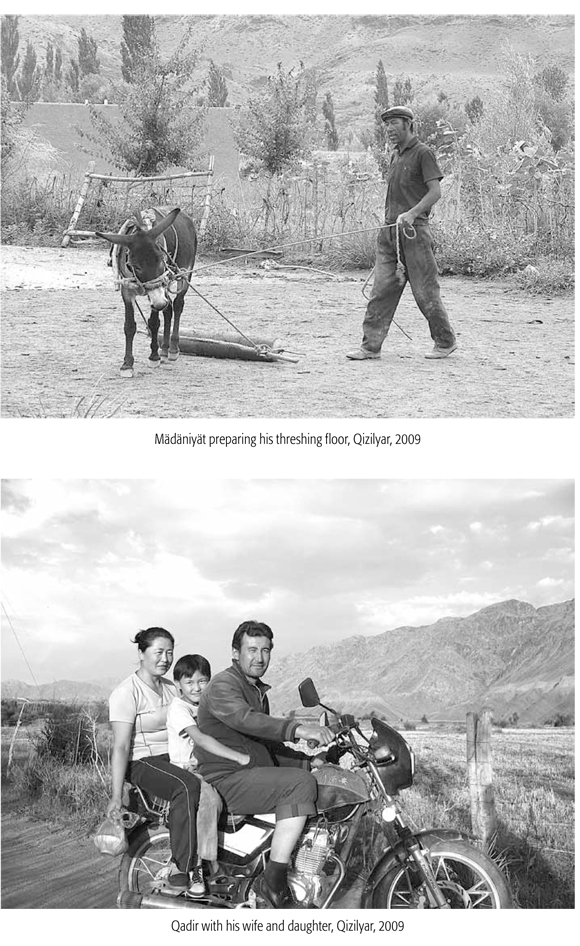

Mädäniyät and Qadir

The preceding section has provided an overview of the rural economy, including the moral economy, of Qizilyar as it has developed in the era of reform socialism. I have shown that, in this variant of socialism, following the chaos of the Maoist years, subsistence uncertainty was definitively banished. Building on infrastructural improvements in the irrigation network dating back to the 1950s, the state nowadays intervenes strongly in almost all domains. Most of these measures are viewed positively, the major exceptions being demographic, linguistic, and religious policies. However, there are also deeper sources of disquiet, which I shall attempt to specify via brief portraits of two individuals, Mädäniyät and Qadir. Mädäniyät means civilization or culture in Uyghur, and it betrays the year of his birth: 1966, when the Cultural Revolution was launched. He was an only child and had little education. He, his wife, and their two school-age children rely on their small plots and have only a few animals and no other source of income, apart from small sums that she earns by selling her embroidery (via intermediaries at the bazaar in Qumul). They have few relatives and do not cooperate significantly with any other households. Mädäniyät feels vulnerable. A long-term sickness makes him often listless and depressed. It is possible that his diet is insufficient to sustain a physique that is much larger than the local norm. He once asked me if I could possibly make enquiries in Europe about some foreign medicine that might improve matters; although he subscribed to the insurance scheme, like everyone else, he did not have enough money to allow him to consult doctors in the city.

Mädäniyät's preoccupation in 2006-2009 was the recurring invasion of mice, which threatened his store of grain and forced him to devise ever more ingenious defense mechanisms. He was not the only villager who had this problem. Poison was available in city shops, but few were willing to spend scarce cash for this item. Mädäniyät saw himself as poor. He and his wife placed great hopes in their young children, who, if they studied well enough, might one day escape from the village, but they were at the same time reconciled to their lot, knowing it to be greatly preferable to the terrible uncertainties of the Maoist decades which had marked their childhood. Mädäniyät felt secure in the knowledge that, in an emergency, help would be forthcoming from the state.11

Qadir is almost ten years younger than Mädäniyät. With support from his father, soon after marriage, he had acquired a new house outside Qizi-lyar, close to the administrative center of the township. His main source of income came from butchering sheep and providing catering facilities for senior officials, in particular Han who were not locally resident. The latter activity was a source of moral anxiety in his own family because it was linked to alcohol consumption, but in addition to giving Qadir a basic grasp of Mandarin, it enabled him to become one of the first young men to own a motorbike. He was officially classified as a peasant and, although living separately, his labor power was still at the disposal of his father. He was obliged to work in the fields alongside other family members when summoned. In return, he received from his father all the grain he needed for his own small household. Qadir and his wife had signed to commit themselves to having just one child and received a significant financial sum for this sacrifice. Like other Party members I knew in the oasis, Qadir explained this political affiliation in instrumentalist terms. He had not volunteered, but the Qizilyar cell was required by higher levels to recruit more members who qualified as dehqanlar. He had agreed because, although he had no wish to attend tedious meetings (and seldom did so), he did not mind paying the price of having to forego regular mosque attendance, which would otherwise have been expected of him. Party membership is a rational step for a would-be businessman almost everywhere in rural China to reduce the risk and uncertainty faced by their enterprises.12

Qadir had cousins who had gone to college and moved permanently to urban jobs. He had not been given this opportunity, but he was doing everything he could to make the best of his fate. Other young dehqanlar in the township would have been grateful for even the small opportunities that had opened up for Qadir. Most have no Mandarin skills at all and usually have to live with their parents for years after marriage. They till the fields and take animals up to the high pastures, and even if they go down to the oasis for seasonal work in late summer, they are expected to hand over the cash they receive to their father. In sum, their lives are characterized by frustration and boredom since, although their subsistence is no longer uncertain, they feel themselves to be imprisoned within an old-fashioned, technologically primitive peasant economy. Their main grievance is not an extractive, exploitative state but the absence of any real opportunity to take risks and break out of the village once and for all. This is what makes rural Xinjiang different from Han-populated regions of the interior, for whom the option to join the "floating population" in the cities is a great deal easier, if only due to the fact that they speak Mandarin. This brings me back to the larger questions broached in the introduction. Even when Uyghur do manage, against the odds, to acquire fluent Mandarin, when they are as qualified as Han applicants or even better qualified, there is evidence that they experience discrimination in urban labor markets (Fisher (forthcoming); cf. Hopper and Webber 2009). These tensions exploded in the regional capital Urumchi in July 2009, when almost two hundred persons were killed in "ethnic rioting".13 I argue that this violence was not a consequence of hunger or absolute poverty, nor of uncertainty. Nor did it have anything to do with religious fundamentalism. Rather, the ongoing tragedy (surely non-functional in evolutionary terms, a clear case of maladaptation) of violence in the XUAR is the result of relative deprivation and the strong perception that discrimination is denying Uyghurs equal opportunities in a territory officially classified as their homeland (Hann 2011).

Conclusions: embedded socialism in china

Qizilyar cannot stand for the whole of eastern Xinjiang, let alone for the southern districts where most Uyghur dehqanlar live. Obviously, the ethnic dimension makes their situation different from that of the rural population elsewhere in China, which for linguistic reasons has a much easier task in joining the urban labor force in the eastern and southern provinces where China's expan-dig economy is experiencing a great shortage of labor. In some regions of rural China where demographic densities are high, environmental endowments poor, and egalitarian land distribution does not suffice to guarantee subsistence, living standards have fallen since the 1980s; here, significant numbers of peasants are effectively compelled to migrate. However, this is the exception. The more common motivation is the will to improve one's lot and escape the boredom and frustration of the peasant condition. Although statistically unrepresentative, the balance between what Karl Polanyi termed the economy's "forms of integration" in Qizilyar resembles that which one finds at the macro level throughout rural China. Reciprocity redistribution, householding and market exchange are all significant. This embedded socialism in the PRC today is not a euphemism for neoliberal capitalism. The Chinese state, unlike postSoviet Russia, has not implemented drastic shock therapy but pursued gradualist policies of marketization and privatization. Key sectors of the economy, including the extractive industries that underpin the boom of recent decades in the XUAR, are still under state control. Labor has been extensively com-modified, but the land (its pendant in Polanyi's conceptualization of "fictitious commodities") remains in the hands of those who farm it. If only because the peasantry, still by far the largest occupational group in China, has not been dispossessed, but on the contrary receives every possible support from the state to provide for its own subsistence, it seems premature to identify a "capitalist road" (cf. Arrighi 2007). Many migrants are able to return to their villages after decades in the cities with at least a small pensionenough to make them materially independent of their rural kin.

However, a peasantry that has not been dispossessed can still be exploited. Although they benefited from the reforms introduced after 1979, there is abundant evidence that the rural population has lost out in recent decades. The wages paid in China's booming factories are kept at the lowest possible level as a result of the government's policiespolicies that ultimately serve the hegemonic interests of the United States rather than the citizens of China as a whole (Hung 2009). Within China, benefits have accrued to new urban elites, but the countryside has been starved of investment and excluded from genuine participation. Income inequality coefficients have risen steeply. Protest is not always a consequence of hunger or absolute poverty; a perception of relative deprivation may suffice, especially when it is accentuated by an ethnic coloring. When socialist accomplishments in terms of reducing existential uncertainty are recognized, but nonetheless felt to be insufficient, the outcomes can intensify other kinds of uncertainty, including political stability.

Following a multiscalar approach, I have argued that Qizilyar and China are instructive for what they reveal about socialism in world history. In its early decades, the PRC was a very bad advertisement for the promise that socialism could, through rational design, achieve better welfare outcomes than the institutions it replaced. The failures of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution have been partially recognized in official historiography (though the extent to which this can be articulated in the public sphere varies with the vicissitudes of politics). Following the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, reform socialists performed much better. In the course of economic decentralization, deep-seated changes in the nature of social and familial relations have been accomplished. Inequalities have increased, but egalitarian landholding and low unemployment rates have virtually banished the fear of fundamental existential uncertainty. The canopy provided by this "giving state" might be compared with the "giving environment" of the Indian forest dwellers studied by Nurit Bird-David (1990).

However, as we have seen, merely banishing the threat of hunger and malnutrition is nowhere near enough to satisfy the aspirations of dehqanlar such as Qadir in Qizilyar. He would like nothing more than the opportunity to move to the city, escape the bonds of patriarchal authority, and take risks in developing his business interests. Such entrepreneurial options, repressed in the Maoist era, are nowadays available in cities such as Shanghai or Guangzhou, but they remain closed to the great majority of rural dwellers. In this respect, Chinese reform socialism has not found a balance that satisfies all population groups. While older generations of peasants are more likely to appreciate the subsistence guarantees and security assured by the present regime, their children and grandchildren have new expectations. For dehqanlar in Tian Shan township, not even the option to swell the ranks of the new urban proletariat is readily available; upward mobility via education has shrunk, and exclusionary pressures have intensified in Han-dominated labor markets.

The original hubris of the central planners was the dream of banishing risk and uncertainty. The omniscient planners would play the role of the auctioneer in neoclassical equilibrium theory, ensuring that all markets would clear and ignoring the noise that a later school of economists would call "transaction costs." In practice, the socialist economies developed different forms of hoarding and "plan bargaining" that led to far greater imperfections. Risk and uncertainty persisted for the planners and the enterprise managers, but the majority of citizens in both industrial and agricultural sectors were well insulated from these deficiencies. In existential terms, social life under the mature varieties of Soviet socialism was virtually risk-free, more secure even than life in the mixed economies (or welfare states or "embedded liberalism") of Western democracies.

Did millions of citizens of the U.S.S.R. and its allies reject this secure canopy twenty years ago? If so, why? Because this security extending well beyond the guarantee of a livelihood, was considered excessive, because it was boring and incompatible with a taste for uncertainty? Does this preference necessarily imply an extension of the market principle in Polanyi's sense? The canopy is changing rapidly in contemporary China, where markets have gained ground but at the same time pensions and social security entitlements are being steadily extended and labor markets are still closely controlled by the state. It is true that decentralization has already led to mass unemployment in the northern "rust belt," and the compromises of China's "embedded socialism" will come under more pressure from global market forces in the future. Would Chinese citizens reject their "giving state" today, if given the opportunity, in favor of an alternative political economy that offered more individual liberty but entailed higher levels of risk and uncertainty? Are democratic elections the only way to resolve such big questions? .

Comentarios

* ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Earlier versions of this paper were presented to interdisciplinary audiences at a conference at Villa Vigoni (June 2011) and at the University of Shihizi, XUAR (March 2013). I am grateful for the discussion on these occasions, for the comments of Antfpoda's two anonymous reviewers, and as always for the advice and corrections of Ildikó Bellér-Hann. The paper derives from our joint project 'Feudalism, Socialism and the Present Mixed Economy in Rural Eastern Xinjiang", funded by the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology; see note 2.

1 The usual distinction between uncertainty and risk is that in the case of the latter it is at least theoretically possible to make a more or less precise calculation of the probabilities (e.g., past experience has shown that one harvest in five is likely to be significantly affected by reduced rainfall).

2 This paper draws on long-term research in Xinjiang carried out jointly with Ildikó Bellér-Hann since the 1980s. For preliminary results concerning the core themes of recent work, see Bellér-Hann (forthcoming). The data presented in this paper were collected between 2006 and 2009 in the eastern oasis of Qumul (Chinese: Hami; the Uyghur form is used henceforth in this paper because Uyghur villagers are the main focus of the analysis). This fieldwork was made possible by a cooperation agreement with Xinjiang University in the framework of a project titled "Kinship and Social Support in China and Vietnam." I am grateful to Arslan Abdulla and Rahilä Dawut in Urumchi and to Sämät Äsra and Busarem Imin in Qumul, although they bear no responsibility for the arguments I develop below. For further detail, see http://www.eth.mpg.de/cms/de/people/d/hann/project1.html.

3 For recent census analysis, see Fisher (2013:65-6). Uyghurs commonly point out that, when the Han populations of the military and the quasi-military colonies of the bingtuan are included, plus large numbers of temporary Han migrants, the Uyghur may no longer constitute the largest nationality of the XUAR.

4 The bingtuan is officially known in English as the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps. This institution has military origins in the Qing colonial era but was formally re-established in the middle of the 20th century after the incorporation of Xinjiang into the PRC. Independent of local and regional government organs, it is often said to constitute a "state within the state." It farms a high proportion of the best land available in the XUAR, mostly on a large scale, using advanced, highly capitalized techniques that contrast sharply with the small units of Uyghur household-based agriculture. See Cliff (2009) for a recent overview. It is directly under the jurisdiction of Beijing, rather than Urumchi.

5 I spent just under three months in Qizilyar between 2006 and 2009. A detailed analysis of the data collected, including the results of an economic survey of all seventy households (all of them Uyghur) has yet to be completed.

6 In spite of these rebellions, nowadays, the Wang are increasingly revered by Qumul Uyghurs as patrons of Uyghur culture and/or as wise and beneficent rulers who redistributed wealth according to the principles of Islam. Violence erupted again throughout the oasis following the abolition of this khanate and its formal incorporation into the province of Xinjiang after the death of the last ruler in 1930 (Bellér-Hann 2012). The main reason on this occasion seems to have been the incursions of Han settlers to appropriate scarce irrigable land (though there is no record of food shortage at this time). Instability continued until the establishment of the People's Republic in 1949.

7 This redistribution, in principle annual, contradicts the principle of long-term lease stability, which is the norm elsewhere, but it meets with the approval of the villagers of Qizilyar.

8 The situation in Kashgar in the 1990s was quite different. In Kashgar, dehqanlarfrequently objected to the obligation to grow cotton, which has never been enforced in the Qumul oasis. Other grievances heard in Kashgar were similarly lacking or present only in attenuated form in Qumul.

9 During a short return visit in March 2013, we found that this tax had been eliminated. This visit revealed further far-reaching changes consistent with the analysis of this paper. Qizilyar senior citizens were paid a small monthly pension from 2011 onward, when this scheme was extended nationwide. Further investigation will be necessary to determine the impact of these changes on family support practices (in some cases, it seems that the money is drawn and retained by younger family members whose cash needs are greater). The most dramatic recent change was the leveling by bulldozer in 2012 of all the old adobe houses of Qizilyar. After temporary accommodation in yurts during the summer, residents took possession of attractive new brick houses erected for them by the state. They were required to pay only 10,000 RMB, barely 10% of the official cost of the building, and even this payment could be eased via credit. This "development" scheme was supposed to facilitate the beginnings of tourism in the valley, since many families would now have enough space to offer rooms to visitors. Public infrastructure was also improved with the construction of new asphalt roads and a piped water network. Moreover, to raise standards of cleanliness, animals were henceforth to be kept in new barns outside the residential center. We were told of plans to extend this scheme to the village next door in the summer of 2013. While the residents of these villages were thus given strong incentives to remain in the Tian Shan township, those of other settlements at higher altitude were encouraged by township cadres to resettle to new housing estates in the oasis, where officials would offer them assistance in seeking urban employment.

10 The five guarantees, first formulated in the mid-1950s, cover essential food, clothing, shelter, medicines, and funeral expenses. The list was later expanded, but it reverted to the original five in the post-Mao period. The precise definition of those eligible to benefit has continued to fluctuate.

11 More help was forthcoming. By 2013, Mädäniyät's fortunes had improved significantly. The state's gift of a new house (see n. 9 above) had seemingly dealt with the rodent problem once and for all. The house interior was almost unchanged from the former adobe building, but he pointed to the small tractor (state-subsidized) with which he now carried out most of the tasks that in 2006-9 he had undertaken with his donkey. Selling his donkey had enabled him to acquire a second-hand motorbike. His daughter had not done well enough in the examinations to proceed to college and was now working in the kitchens in the central offices of the township. He was still hopeful that his son might escape from the village by the educational route.

12 By 2013, Qadir had been appointed Deputy Secretary of the village. He was very active in the implementation of the redevelopment summarized above (see footnote 9). He and his wife had also sought and been granted permission to have a second child; they were now the proud parents of a son, twelve years younger than his sister; yet he remained dependent in numerous ways on his father, especially in matters concerning their joint farming activities.

13 Although independently verified data are hard to come by, it is widely accepted that many of the Uyghurs involved in the riots were not registered city dwellers but hailed from the countryside in the south of the XUAr (for further analysis, see Millward 2009). There was no evidence of any participants from Qumul. However, a major incident in nearby Turfan in April 2013 shows that Uyghur unrest is no longer confined to the south, where they are demo-graphically dominant.

References

1. Arrighi, Giovanni. 2007. Adam Smith in Beijing. Lineages of the Twenty-first century. London, Verso. [ Links ]

2. Bellér-Hann, Ildikó. (Forthcoming). Strategies of Social Support and Community Cohesion in Rural Xinjiang', Asien - the German Journal on Contemporary Asia. [ Links ]

3. Bellér-Hann, Ildikó. 2012. Feudal Villains or Just Rulers? The Contestation of Historical Narratives in Eastern Xinjiang. In Local History as an Identity Discipline. Special Issue of Central Asian Survey 31(3) eds. Svetlana Jacquesson and Ildikó Bellér-Hann pp. 311-326. [ Links ]

4. Bellér-Hann, Ildikó. 2008. Community Matters in Xinjiang: Towards an Historical Anthropology of the Uyghur, 1880-1949. Leiden, Brill. [ Links ]

5. Bellér-Hann, Ildikó. 1997. The Peasant Condition in Xinjiang, Journal of Peasant Studies 25 (1): 87-112. [ Links ]

6. Bellér-Hann, Ildikó and Chris Hann. (Forthcoming). Magic, Science and Religion in Eastern Xinjiang. In Ildikó Bellér-Hann, Birgit Schlyter and Jun Sugawara, eds., Kashgar Revisited. Istanbul, Swedish Research Institute. [ Links ]

7 Benda-Beckmann, Franz von and Keebet von Benda-Beckmann. 1994. Coping with Insecurity. In Coping with Insecurity: An 'Underall' Perspective on Social Security in the Third World, eds. Franz von Benda-Beckmann and Hans Marks, pp. 7-31. Utrecht, Stichting Focaal. [ Links ]

8. Bird-David, Nurit. 1990. The giving environment: Another Perspective on the Economic System of Hunter-gatherers, Current Anthropology 31, pp. 183-96. [ Links ]

9. Cashdan, Elizabeth (ed.). 1990. Risk and Uncertainty in Tribal and Peasant Economies. Boulder, CO, Westview Press. [ Links ]

10. Cliff, Thomas M. J. 2009. Neo Oasis: The Xinjiang Bingtuan in the Twenty-first Century, Asian Studies Review 33 (1), pp. 83-106. [ Links ]

11. Fei, Hsiao-Tung. 1939. Peasant Life in China. A Field Study of Country Life in the Yangtze Valley. London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, pp. 29-68. [ Links ]

12. Fisher, Andrew. (2013). A Comparative Analysis of Labour Transitions and Social Inequalities in Tibet and Xinjiang. In On the Fringes of the Harmonious Society. Tibetans and Uyghurs in Socialist China, eds., Ildikó Bellér-Hann and Trine Brox, pp. 29-68. Copenhagen, NIAS Press. [ Links ]

13. Foster, George M. 1965. Peasant Society and the Image of Limited Good, American Anthropologist, 67/2, pp. 293-315. [ Links ]

14. Geertz, Clifford. 1963. Agricultural Involution. The Processes of Ecological Change in Indonesia. Berkeley, CA, University of California Press. [ Links ]

15. Goody, Jack. 2003. Sorcery and socialism. In Distinct Inheritances. Property, family and Community in a Changing Europe, eds., Hannes Grandits and Patrick Heady, pp. 391-406. Münster, LIT. [ Links ]

16. Guyer, Jane. 2009. Composites, Fictions, and Risk: Toward an Ethnography of Price. In: Market and Society: the Great Transformation Today, eds. Chris Hann and Keith Hart, pp. 203-220. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

17. Häbibulla, Abdurähim. 1993. Uyghur Etnografiyisi. Urumchi, Xinjiang Hälq Näsriyati. [ Links ]

18. Hann, Chris. (2013). Harmonious or Homogenous? Language, education and social mobility in rural Uyghur society. In On the Fringes of the Harmonious Society. Tibetans and Uyghurs in Socialist China, (eds.), Ildikó Bellér-Hann and Trine Brox, pp. 183-208. Copenhagen, NIAS Press. [ Links ]

19. Hann, Chris. 2012. Ritual Commensality and the Mosque Community in Eastern Xinjiang. In Articulating Islam: anthropological approaches to Muslim world, eds., Magnus Marsden and Kostas Retsikas, pp. 171-191. Dordrecht, Springer. [ Links ]

20. Hann, Chris. 2011, Smith in Beijing, Stalin in Urumchi: Ethnicity, Political Economy and Violence in Xinjiang, 1759-2009, Focaal. Journal of Global and Historical Anthropology 60, pp.108-323. [ Links ]

21. Hann, Chris. 2009. Embedded Socialism? Land, Labour, and Money in Eastern Xinjiang. In Market and Society: The great transformation today, eds., Chris Hann and Keith Hart, pp. 256-71.Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, [ Links ]

22. Hann, Chris. 1999. Peasants in an Era of Freedom; Property and Market Economy in Southern Xinjiang, Inner Asia 1 (2), pp. 195-219. [ Links ]

23. Hann, Chris and Keith Hart. 2011. Economic Anthropology. History, Ethnography, Critique. Cambridge, Polity Press. [ Links ]

24. Hart, Keith, Jean-Louis Laville and Antonio David Cattani (eds.). 2010. The Human Economy. A Citizen's Guide. Cambridge, Polity. [ Links ]

25. Harvey, David. 2005. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

26. Hayek, Friedrich A. 1943. The Road to Serfdom. London. Routledge. [ Links ]

27. Heady, Patrick (ed.). 2010. Family, Kinship and State in Contemporary Europe. Frankfurt, Campus. [ Links ]

28. Hopper, Ben and Michael Webber. 2009. Migration, Modernization and Ethnic Estrangement. Uyghur Migration to Urumqi, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, PRC, Inner Asia 11, pp. 173-203. [ Links ]

29. Hung, Ho-Fung. 2009. America's Head Servant? New Left Review 60, pp. 1-25. [ Links ]

30. Lee, Richard B. 1979. The !Kung San: Men, Women and Work in a Foraging Society. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

31. Millward, James A. 2009. Introduction. Does the 2009 Violence Mark a Turning Point? Central Asian Survey 28, pp. 347-360. [ Links ]

32. Ortiz, Sutti R. 1973. Uncertainties in Peasant Farming. A Colombian Case. London, Athlone. [ Links ]

33. Parish, William L. and Martin King Whyte. 1978. Village and Family in Contemporary China. Chicago, University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

34. Polanyi, Karl. 1977. The Livelihood of Man ((ed.) Harry Pearson). New York, Academic Press. [ Links ]

35. Polanyi, Karl. 1968. Primitive, Archaic, and Modern Economies. Essays of Karl Polanyi. New York, Anchor Books. [ Links ]

36. Polanyi, Karl. 1944. The Great Transformation. The Political and Economic Origins of Our Times. Boston, Beacon. [ Links ]

37. Sahlins, Marshall. 1972. Stone Age Economics. Chicago, Aldine. [ Links ]

38. Scott, James. 1976. The Moral Economy of the Peasant: Rebellion and Subsistence in Southeast Asia. New Haven, CT, Yale University Press. [ Links ]

39. Starr, S. Frederick (ed.). 2004. Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland. Armonk, New York, Sharpe. [ Links ]

40. Tawney, R. H. 1932. Land and Labour in China. London, George Allen and Unwin. [ Links ]

41. Yan, Yunxiang. 2009. The Individualization of Chinese Society. Oxford, Berg. [ Links ]

42. Yurchak, Alexei. 2006. Everything Was Forever Until It Was No More, Princeton, Princeton UP. [ Links ]