Who and what constitutes the “peasantry” have long been a foil for intellectual debates about modernity, capitalism, and political change.´ Demographically, there are more peasants farming today than ever before in human history-between 500-560 million self-provisioning farms that feed at least 2 billion people globally (Ploeg 2018). Yet, much like indigenous people, peasants were predicted to disappear in the twentieth century. Akin to Colonel’s Richard Henry Pratts’ infamous slogan for Native American boarding schools as aiming to “to kill the Indian, save the man,” peasants faced state policies meant to kill the self-producer, but save the body for wage labor. Recurring binary tropes about peasants as obstacles to “progress” are startlingly similar to the spectrum of derogatory and/or romanticized stereotypes about Native Americans as obstacles to “civilization” (Mihesuah 1996).

After Stalin murdered the great rural economist Alexandre Chayanov to quash his empirically-proven vision for small-scale agriculture within the modern nation-state ([1924] 1986), both communists and capitalists alike have treated peasants with suspicion. Anxious they might not join the class struggle, Marx himself infamous described peasants as “potatoes in a sack.” In turn, Cold War agrarian studies sought to understand the revolutionary potential/threat of peasants as an unstable social category that failed to align with class schemata. Revolt they did. However, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, armed peasant insurgencies surrendered their vanguardist dreams to seize state power and, one by one, negotiated Peace Accords, including Guatemala in 1996.

Under neoliberalism, peasant uprisings are more likely to block pipelines and other megaprojects of global commerce than to toss Molotov cocktails into military barracks. Whereas Latin American states once could offer resources to co-opt and assimilate indigenous peasants, structural adjustment throughout the region has devastated state services. With politicians budgeting fewer and fewer resources to clientelist rural programs, peasants have less to lose by embracing indigenous identity (Yashar 1998). Perhaps their most powerful resistance has been their persistence. Working against a slew of pro-corporate agribusiness policies and subsidies, peasant leaders describe their communities’ bodily, cultural, and economic struggles to survive in a hostile world with phrases like Estamos luchando para la vida (We are fighting for life).

Seven years ago, I spent the winter holidays exchanging collaborative grant proposal texts with Don Pablo Tux,1 a catechist turned community organizer who has led for the past two decades a peasant federation in northern Guatemala called “Asociación de Comunidades Campesinas Indígenas para el Desarrollo Integral de Petén” (ACDIP), the Indigenous Peasant Association for the Integrated Development of Petén. Reviewing those rough drafts, I can see that much like other indigenous movements in the Americas dealing with structurally-adjusted and increasingly technocratic states (Yashar 1998), he initially framed the project as an effort to confront the structural violence of neoliberalism,

. . . as a defense of the development rights that are being violated by the economic model that the Governments and the Transnationals have implemented, which threatens [our] life and natural resources since land grabbing has accelerated by the Big Companies that are dedicated to [plantation] monoculture and installing Hydroelectric Dams in the Great rivers. (Capitalization for rhetorical emphasis, his, December 2012)

Having talked with the foundation’s program officer to ascertain the flexibility and scope of the multi-year grant, I suggested in track changes that they might describe how ACDIP aspired "to recover principles, values, ancestral cultural values, principles, and Maya worldview through a methodology of exchanges based on cultural concepts of reciprocity, li xeel in Q’eqchi’ Mayan.” I vividly recall Don Pablo asking me over our next Skype call, “You mean we can propose to use these funds to explore our indigenous identity?” Yes! I explained, that’s precisely what this donor wants!

With this aperture, they tirelessly transformed themselves over the next six years from a traditional peasant organization focused on land rights into a major cultural movement for agro-environmental justice and restoration and indigenous autonomy. No longer having to compete with other NGOs for scarce donor funds, they retreated from their city office to a regional town closer to their base communities-initially sharing an office with a spiritual elders’ association Oxlaju Tzuultaq’a (13 Mountain Spirits), but eventually rented their own bleak concrete block house a few doors down. Reflecting on these transitions as we set to work this past summer drafting a plan for recovery of sacred sites and territorial reforestation, Don Pablo recalled earlier mistakes trying to mobilize the force of peasant disobedience to topple a corrupt governor in 2001. “We didn’t have depth. We lost control. I was a fool [with a slightly vulgar expression].” After spending a year underground to avoid arrest, he and his long-term co-leader, Rigoberto Tec, returned from rock bottom to more cautious organizing that any Gramscian scholar reading this might recognize as a retreat to a classic war of position until a frontal war of maneuver becomes possible.

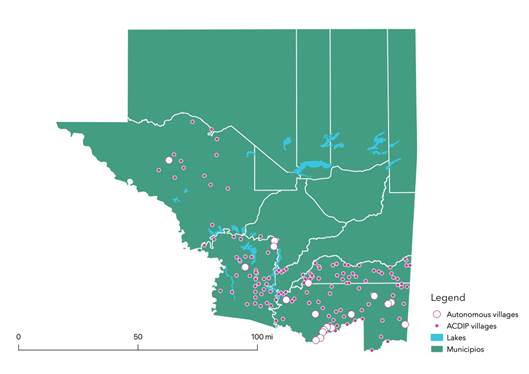

They steadily built their membership from 31 villages to 162 and counting that cover about a tenth of Guatemala’s area (see Figure 1). The corrupt governor has since died in jail. An ever-youthful Don Pablo dreams of establishing a parallel indigenous parliament that could channel funds from the governor’s office to be administered directly by the autonomous villages. He spoke fluidly with me about their expansive vision, “I cannot just defend my rights as a person, but we have to defend ourselves as a people. We must defend the right to our wisdom, to defend the language, our dress, our culture, our songs, our weaving, for without these, we are just serfs again without convivencia (conviviality), without harmony” (Fieldnotes 2019). For Don Pablo and comrades, indigenous autonomy is simultaneously a state of mind, a sense of dignity, and a non-marketized mode of living as self-provisioning peasant producers.

As Polanyi (1944) taught us, when the motor of raw capitalism has plundered too much and left too little for social reproduction, movements will spontaneously arise or morph to re-embed the runaway economy within the controls and contours of cultural life. As people on the brink of survival, for peasants, it can be hard to sustain perpetual protest. At some point, social movements must move de protesta a propuesta (from militant protest to counter-proposal)-a pan-American slogan about the transition from being “anti”-globalization to envision “alter”-globalization. While sovereignty remains the North American frame for Native self-determination, throughout Latin America (Abiayala) the aspirational category for de-colonization is autonomy-both within and alongside the state.

Manifesting two decades of allied work with ACDIP, this article traces their dramatic shift from organizing with an external class-based peasant identity to their current road for indigenous autonomy. The catalyst for this transition was a sudden awareness about the paucity of the “leftovers” (li xeel, in Q’eqchi’ Mayan) that segued into a field campaign for territorial defense. As they began to organize villages to stop selling parcels to narcos, ranchers, and palm oil plantations, Don Pablo realized, “they could not fight for ancestral lands without ancestral values” (Fieldnotes 2019). As we know from the earliest case studies in legal anthropology (Nader 1969), the resilience of customary decision-making is its vernacular capacity for temporal improvisation to changing context. What is old may become new again. While carving novel structures (territorial, political, legal) in which to manage their own affairs, ACDIP’s process of “de”colonization has creatively adapted an oppressive political structure from 16th-century colonial rule into a creative political mechanism to defend their territory from 21st-century neoliberal land grabs.

Autonomy and Indigenous Law in “Latin” America, Back to the Future

As a concept derives from the Greek -autos (self) and nomos (law) (Blaser et al. 2010, 5)-autonomy resonates at multiple levels. For the individual, it refers to a person’s capacity for agency and self-actualization-and, therefore, is a common core concept for women’s rights or as a creative space for artistic production. In some places, indigenous peoples articulate the concept as self-determination or self-government independent of nation-state hegemony (Blaser et al. 2010). However, nation-states themselves also aspire to protect their internal affairs from one another. All this is to say that autonomy is not exclusionary; as suggested by Habermas, individual, collective, and meta-level autonomy can be mutually reinforcing or mutually antagonistic.

Indigenous leaders often proactively transcend these layers-for example, working transnationally to secure rights to autonomy against hostile nation-states. In turn, the experience of being heard, recognized, and “taken into account” (a phrase commonly used in Guatemala)-for example at the United Nations-raises both individual and collective self-confidence. Put another way, the practice of seeking autonomy can redefine identity (Blaser et al. 2010). Although states have often misinterpreted autonomy as a secessionist threat to the nation, indigenous peoples of the Americas are merely seeking respectful co-governance based on principles of plurality and relationality (Blaser et al. 2010). As refracted in the Zapatista struggle in Mexico, autonomy was not a move to seize state or political party power, but to exercise endogenous power.

Although autonomy is inherently place-based, plural, and vernacular, in “Latin” America, it retains a logic of practice (Bourdieu 1980) of how Spanish colonial systems homogenized and lumped the diverse peoples of the Americas into the generic (and mistaken) category of Indian (Bonfil 1996; Keme and Coon 2018). Having confronted the same colonial, Iberian hegemony, diverse indigenous peoples across the Americas today share commonalities in their political-religious systems of “customary”2 or indigenous law (including the southwest United States). Although the Spanish colonial system was imposed upon them as a cargo (burden) to collect tithes, taxes, and conscript labor for the colonizers, whenever possible, indigenous people infused new meaning to these institutions with syncretic traditions (Bonfil 1996). Largely organized at the municipal level or what Eric Wolf (1957) famously depicted as “closed corporate communities,” these systems of indigenous law are known in some places as usos y costumbres (customs and uses) and in others as “customary law.”

As an unwritten and uncodified system, indigenous law is generally understood to be situational, fluid, and adaptive. Like all colonizing powers, the Spanish conscripted, coopted, and utilized local governance systems to maintain indirect colonial rule where they lacked sufficient settler presence to impose a foreign administrative system. As Nancy Farriss (1984) argued in her prize-winning ethnohistory of Yucatan, Spanish colonial rule was more of a parasite that feeds off its host than a settler clone of Spain. To survive the relentless extraction of their resources and labor, indigenous communities used the veneer of imperial structures to protect community traditions, resolve conflicts internally out of the purview of states, and maximize their power to manage their own affairs. They also learned the colonizer’s law. Indigenous leaders proved adept at appealing across the Atlantic to negotiate justice-writing copious complaints about colonist abuses to the Spanish Crown and the Catholic hierarchy (through allies like Bartolomé de las Casas) (Restall, Sous, and Terraciano 2005). They even established elaborate workshops to forge land documents (Wood 2019).

Although outsiders may not be able to grasp the fluid and dynamic boundaries among religious, spiritual, and legal codes in customary law, for members of any community, its unwritten principles make perfect sense in context. From the local point of view, it is sovereign state law that seems arbitrary and nonsensical. Ergo, Sieder (1997) suggests that the task for legal scholars is not to act as arbiters about the veracity or authenticity of customary law, but to understand the changing contexts by which customary law persists, evolves and re-flourishes. As Laura Nader (1969) and her students demonstrated in ethnographies around the world, law, in its clearest form, is a process by which people keep the peace (or balance) so as to live fulfilling lives, however situationally defined.

For certain, the colonial world was also pluri-legal. Spanish colonists themselves took customary advantage of distance and communication delays to resist certain royal edicts. Shaped culturally by the Christian “reconquest” of the Iberian peninsula, which had financed itself by rewarding soldiers with landed estates for their military exploits, Spanish conquistadors considered themselves similarly entitled to the spoils of war in the Americas. A phrase that captured this Creole principle of selective legality was obedezco pero no cumplo (I obey but do not comply). For example, long after Charles V abolished slavery with the 1542 “New Laws of the Indies,” both de jure and de facto servitude persisted throughout the Spanish empire (Reséndez 2016). This is to emphasize that indigenous customary law was not an anomaly, but one of several legal and political systems simultaneously operating within the Spanish colonial empire.

As a gesture towards contemporary pluri-legalism, governments in the Andean region have tentatively begun to integrate conceptual space for cultural autonomy and endogenous development into their constitutions, albeit to a “limit point” over control of subsurface resources like petroleum (González 2015). Throughout the hemisphere-and indeed far beyond their own territories-indigenous peoples are articulating visionary theories of the “good life” (buen vivir), sumak kaway in Kichwa, convivencia in Mexico, küme mongen in Mapuche, “life projects” in Canada, and other emergent expressions of a moral economy (Gudnyas 2011).3 Indigenous movements throughout Latin America also share commonalities in their agendas for political inclusion and bi-lingual/bi-cultural education (Yashar 1998). The deeper test, of course, is whether such expressions of cultural autonomy can flourish without free self-determination for territorial governance. In Bolivia, indigenous/peasant entities have won the rights to form larger territorial units by aggregating themselves via referenda and consultations.4 The Ecuadorian constitution opens a similar possibility for combining territorial governance into larger “circumscriptions” (Article 247, cited in González 2015).

In a masterful survey of these and other Latin American movements, González (2015) identifies three current patterns of how indigenous autonomy is forged discursively in an “upwards” direction towards supra-sovereign spaces. In those countries where indigenous people found themselves engaged in armed conflict or resistance to illegitimate state/military power, autonomy presents itself as a pathway to peace, truth reconciliation, and re-establishment of good governance. In places where indigenous territories have been threatened by development institutions, autonomy is often discursively constructed around international human rights frameworks and around principles of free, prior informed consent (FPIC). Finally, in contexts where indigenous mobilizations evolved from neoliberal business threats to resources, he argues that autonomy tends to have high “territorial content” (13) and alignment with the rights of nature. Having survived decades of a genocidal civil war only to lose their farms to land grabs induced by a World Bank project, Q’eqchi’ expressions of peasant autonomy in Guatemala seem to share all three of these. However, to be sustained, they have also nourished an “inward” cultural re-constitution of traditional forms of self-governance.

Methods with Movement(s)

Of course, states are not the only external actors whom indigenous peoples apprise to present discursive claims for autonomy. To win the support of nonprofit people and other international sympathizers, Amazonian peoples, for example, have shifted the framing of their territorial struggles from human rights to biodiversity conservation with strategic essentialisms (Conklin and Graham 1995). Having accompanied Central American peasant movements over many generations, although much of the leadership is constant, Edelman (1999) has witnessed similar shifts of discourse. Yet, peasant organizations are also complex, multi-hydra masses with their own internal conflicts and gender struggles. To what faction and discourse does the allied ethnographer commit? What voices fall by the wayside? (Edelman 2001, 311) As he cautions in another article, when researchers are “unable to transcend a class- or nationality-stereotyped presentation of self in the field,” they are “likely to receive formulaic responses” (2005, 38). As Mattice (2003) noticed, national leaders tend to speak to her in more abstract terms of indigeneity, whereas within Chiapas, local leaders focused more on the everyday praxis of agrarian autonomy (land reform, markets, credit, etc.)

By personal circumstance and conscious political choice, I am shifting my own scales of engagement from everyday rural ethnography to more regional work as an expert witness on resource conflicts throughout Q’eqchi’ territory. Although I have transitioned from fine-grained village work to a more birds-eye vantage of movements, thousands of pages of qualitative field notes from seven years of community-level fieldwork undergird my understanding of Q’eqchi’ law and principles of autonomy (see Figure 2). I apply the same inductive spirit of village observation to my attuned listening to ACDIP’s leaders se’ kaxlan k'aam ch'ich' (over Skype and other digital platforms) to recognize performative discourse. Given the propensity of Guatemalans to communicate content through allusions (indirectos), I also take care to read between the lines of texts, posts, telephone conversations and often verify content with third party friends and colleagues outside their networks. This triangulation is important because jealousy and rumors fly quickly in Petén among balkanized nonprofits competing for scarce donor funds (Sundberg 1998).

I first met ACDIP’s leaders seventeen years ago when I was working on my dissertation in the early 2000s. Then I reappeared in their lives with a study on land grabs in 2010. For the last decade, they have incorporated me as a closer strategic advisor, fundraiser, and bearer of informational resources. I am also an incorrigible connector and have been responsible for introducing them to other Q’eqchi’ thought leaders across the lowlands that have independently shaped and nourished ACDIP’s current movement for autonomy. In sum, I harness the privileges afforded to me to open doors for their movement but take pains to make clear that risk-evaluation, management, and representational decisions in our collaboration are ultimately theirs, as the genocidal violence of the Guatemalan civil war remains all too fresh in our minds.

Leadership in Post-Peace Guatemala

Although the Q’eqchi’ were previously a deeply egalitarian people governed by consensus, the appointment of village “military commissioners” during the civil war transformed community decisions into more hierarchical and authoritarian processes (Sieder 1997). Not only did village commissioners file intelligence reports, but they often carried quotidian village disputes to the base for arbitrary resolution by their commanders. As one elder remarked to Rachel Sieder (1997, 50), ‘With the war, we lost our memory’-that is, if they survived at all. In the context of genocide, many Q’eqchi’ people converted to evangelism to protect themselves from the military. In turn, missionaries presented the Christian God as deeply authoritarian with powers of surveillance and control over labor akin to a plantation owner (Wilson 1991). The military was less subtle. As part of Rios Montt’s counter-insurgency strategy, they confined a significant portion of lowland Q’eqchi’ refugees into “strategic hamlets” where they were re-educated, reorganized into civil defense patrols, and surveilled around the clock. Previously settled in dispersed hamlets or homes in their maize fields, the jumbling of refugees into close settlement brought new types of disputes that were resolved by the dictates of military commanders.

In my own fieldwork experiences in Petén starting in 1993, villagers continue to fear their ex-military commissioners. Even during my dissertation fieldwork six years after the peace, after taking up village residence, someone always quickly made sure that I was aware who the military commissioner had been and subtly warned me to be cautious in approaching their family. Quite often the commissioners became the new “presidents” of community improvement committees (comités de promejoramiento) established during demilitarization of the early 1990s and/or on the “voluntary committee for peace” established after the civil war (Sieder 1997, 48). As NGOs and governmental agencies flooded selected communities with development projects, more committees proliferated - water councils, women’s crafts, corn grinding mills, whatever donors had to offer-and leadership positions were often taken by commissioners. Villagers complained quietly to me about false leaders, corruption, vanguardist assemblies in which they had “not been taken into account,” and general coordination problems.

The few autochthonous Maya organizations that survived the violence were “comparatively weak and fragmented,” and dependent on international brokers who poured money into rebuilding civil society after the Peace (Sieder 2011, 44). With support from the United Nations for workshops, the Maya movement surged forward with a cultural agenda at a national level. Indigenous leaders secured a nominal seat at the table, but it was only partial recognition, largely without material power or agrarian reform. As Maya intellectual Dr. Demetrio Cojti remarked to anthropologist Charlie Hale, “Before the state simply told us ‘no’, now we live in a time of ‘sí pero’ (2002, 509)” . Hale paints a devastatingly accurate observation of how neoliberalism can draw indigenous people into protracted “dialogue. . . and if well-connected and well-behaved, they are invited to an endless flow of workshops, spaces of political participation, and training sessions on conflict resolution” (Hale 2004, 18).

This produced a division, if not a schism, in the Maya movement between cosmopolitan culturistas (what might be termed “culture warriors” in the North American academy) and those working on material/class issues (Warren 1998). On the whole, the former reaped international donor funds after the peace, while rural and peasant organizations were left in the cold. The “permitted Indian” (Hale 2004) was colorful, multicultural, cultural, but rarely, if ever, agrarian. For example, Hale recounts a conversation with a USAID program officer who felt that the peasant federation CONIC (National Indigenous and Peasant Coordinator) fell outside of their funding programs for “civil society” (Hale 2002). Likewise, in Petén, a more culturally-oriented federation of elders Oxlaju Tzuultaq’a enjoyed the general support of international donors, while the peasant organizations that evolved into ACDIP initially struggled to find funding for their land work. These were, however, false divides, as some Q’eqchi’ leaders like Don Pablo Tux served on both the boards of the culturista and peasant associations. Beyond mediating land disputes, he can play the marimba with virtuosity.

All this is to say that identity is creatively and contextually produced in relationship to the external world, as a response to repression, but can also be a proactive and self-conscious articulation of group-identity (Bonfil 1996). Even as they indigenize their strategies for autonomy with savvy external representations of new identities, resistance movements nonetheless maintain vestiges and tools of their prior formations. While Ladino (mestizo) peasants in Petén now tend to describe themselves as agricultores (farmers), small Q’eqchi’ producers have continued to hold onto peasant identities and dignity in household provisioning. They take pride in being connected to a transnational peasant federation, Via Campesina. Like this international umbrella movement (which includes a surprising number of small farmer associations from the global North), ACDIP’s political platform revolves around the “right to continue being agriculturalists” (Edelman 2005) in this generation and the next. Also reflective of Via Campesina’s strategic decision to remain autonomous of allied NGOs that sometimes overstepped boundaries to ‘manage’ the tactics of peasant movements (Martínez-Torres and Rossett 2010, 158), ACDIP’s membership still regularly springs into militant political action-blocking roads and joining national marches. When funds fall short, ACDIP’s leaders themselves return to planting maize to sustain their families. All this is to say that even as they indigenize their strategies for autonomy, as a social movement they nonetheless continue to draw from the “deep reservoir” of the tools, tactics, and power analysis of their prior agrarian/peasant organizing (Edelman 2005). Ergo, I mirror the language of ACDIP’s leadership who continue to identify as campesino in their personal life histories. To compare with naming debates in the United States, while the term “Native American” might seem more politically correct, the late Russell Means once quipped, “We were enslaved as American Indians, we were colonized as American Indians and we will gain our freedom as American Indians, and then we will call ourselves any damn thing we choose” (Mann 2005, 394).

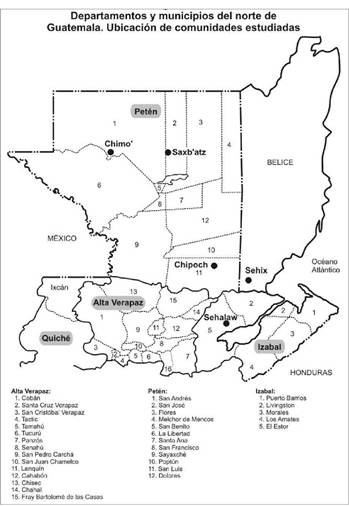

Becoming Q’eqchi’ Peasants

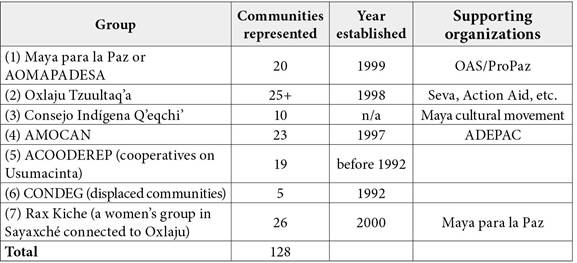

When I first met ACDIP’s leaders, like so many peasant movements in places where colonialism left grotesquely unequal land distribution, they were understandably preoccupied with securing land rights and access to land. After the Peace Accords, various groups in Petén then formed a coordinating committee called COINCAP (Coordinadora Indígena Campesina y Popular de El Petén). In January 2000, by a popular assembly vote of 87 leaders, they decided to formalize the committee to “represent and make visible” their need for land by affiliating with the National Coordinator of Peasant Organizations (CNOC). Even so, they maintained a coalition of seven subgroups (Consejo Indígena Q'eqchi', ACOODEREP, AMOCAN, Oxlaju Tzuultaq’a, Asociación Junkabal, Organización Maya para la Paz y el Desarrollo)-all mostly Q’eqchi’ but not exclusively so.

Having heard that there was a gringa wandering around Santa Elena who spoke decent Q’eqchi’, they invited me to attend a day-long strategic planning meeting in 2003 at a rented discotheque in town. Alas, both my dancing and linguistic skills proved unnecessary, because the sedentary meeting was held in Spanish to accommodate the Ladinos present (roughly a fifth of the 52 men and 7 women in attendance). A Spanish-language banner framed the meeting with a CNOC slogan, “For a future without hunger, no more large holdings (latifundios)! Agrarian reform is urgently needed!” As part of its country-wide strategic planning, CNOC wanted them to answer a series of western planning questions like “What are we going to do? How? When? With what resources? Who?” They spoke of “food security” rather than the more indigenized concept of “food sovereignty.” While “indigenous rights” were discussed, they were buried among more secular list of focal areas: “land, integrated community development, gender/women, indigenous rights, communication, organizational strengthening, territorial defense, and natural resource defense” (Fieldnotes 2003).

Shortly after that meeting, they changed their name from COINCAP to COCIP (Coordinator of the Peasant and Indigenous Organizations of Petén), thereby dropping “popular movements” from the name, but continuing to express a hybrid peasant and indigenous identity. Although legally a branch of CNOC, locally they were still known as COCIP with the same seven sub-regional groups. Over the next several years, as COCIP/CNOC-Peten, they played a decisive role in helping their member communities secure land titles during a chaotic cadastre financed by a World Bank loan (Grandia 2012). Once land titles were secure, however, the Ladino communities drifted away. Albeit grateful for support from CNOC’s central office, COCIP’s subdirector also noted that “[CNOC’s] actions were oriented to and highlighted the subject of land and the peasantry, but neglected aspects of [the] identity of the ethnic majority that constituted [CNOC]” (see Table 1).

By mutual agreement, by 2007, COCIP amicably separated from CNOC to become their own nonprofit (“association” in Guatemalan legal terms) for which they chose the name ACDIP, with “indigenous” now fused as an adjective for campesino. Through all these reorganizations, one may note that the phrase “integrated development” persisted in their name. A global buzzword trickling down from United Nations meetings, it refers to coordinated multi-sectoral projects that would, for example, unite women’s issues, health, and other social concerns alongside economic development. However, in these spaces of peasant organizing in Petén, it was more of a placeholder for holistic indigenous identity, a signifier for dignity, and an allusion to agrarian reform. When by 2019, ACDIP inaugurated a Q’eqchi’ high school, INDRI (Indigenous Institute for Integrated Rural Development), the concept remains enshrined in the students’ accredited degrees as “community organizers for integrated development.”

During this time, they subsisted on tiny grants from the United Nations Development Programme, MINUGUA (the United Nations peace monitoring team), The Global Lutheran Foundation, Action Aid (UK and US), and others who gave locally for projects and leadership training. In a report summarizing this time period, ACDIP’s leaders drew up a list of 25 remarkable accomplishments. They were a mix of the settlement of land claims, participation in government bodies, organizational capacity, negotiations in high-level fora, work towards a national policy for integrated community development (PNDRI, National Policy of Integrated Rural Development), conflict resolution, and other more general indices of political influence. Almost buried among the others were three qualitative achievements towards autonomy:

“interlocutor role between the State and [indigenous] community demands”;

“having achieved a precedent on the issue of discrimination as an indigenous Mayan Q’eqchi’ people in Petén”; and

profundamente arraigado poder de convocatoria that I might translate as “a deep capacity to convene and call to assembly.”

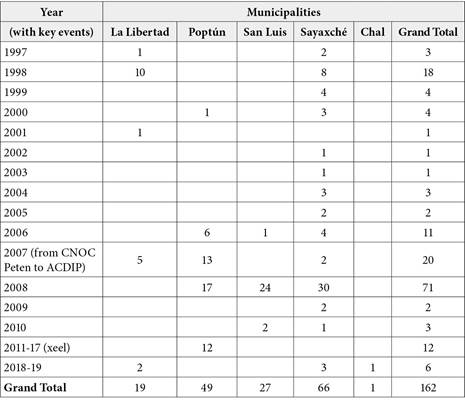

The latter is almost hilariously understated because even before the “Xeel” project (see below), ACDIP had expanded its base membership to 144 villages (see Table 2).

The only civil society sectors or social movements I have witnessed over the last 27 years that have sustained anywhere near this kind of grassroots mobilization are (in no particular order): a women’s organization (Mujeres Ixqik) that evolved out of donor-supported Women’s Forum, the Catholic Church’s social parishes, a regional association for health promoters and midwives, and the forest concession communities of the Maya Biosphere Reserve. While other Q’eqchi’ associations have organized ephemerally at the micro-regional (via highway routes) or municipal level (Grandia 2018), ACDIP now represents essentially half of all rural Q’eqchi’ communities in Petén. It is clearly the largest and most enduring Q’eqchi’ movement emerging in Petén since the signing of the 1996 Peace Accords, in part because of consistent core leadership. While venting about how a donor failed to understand the voluntary and long-term character of social movement leadership, Don Pablo muttered in a text, “If the communities didn’t trust me, they would have voted me out.” Although ACDIP now has the façade and legal status of NGO (an office, an accountant, by-laws), it nonetheless remains identified as a social movement, often signing messages with the famous refrain from a sacred Maya text, the Popol Vuh, “Let everyone stand up, let no one be left behind, let us not be one or two of us, but all of us.”

Xeel, the Leftovers

Don Pablo attributes this organizational transition towards autonomy to what they learned from a 2010 investigation I led to measure the severity of land grabs following a 1998-2007 World Bank land administration project (Grunberg, Grandia, and Milian 2012). A decade later, he reflected, “Our hair may be grey, but that study will live on.” Through analysis of the property registry, my technical team documented that peasant communities in northern Guatemalan had lost 46 percent of their land in less than a decade. Through participatory mapping, ACDIP’s regional coordinators then validated that data within one percentage point. After submitting our report to the World Bank and the Government of Guatemala, another Petenera colleague and I co-authored a bilingual popular booklet in colloquial Spanish, which ACDIP’s then sub-director translated to Q’eqchi’.

Alarmed by the study results, a sympathetic program officer from the InterAmerican Foundation (IAF) invited a proposal from ACDIP for territorial defense strategies-the first time his agency had offered to support a social justice movement rather than a community development project. The initial idea was to disseminate two thousand copies of the popular booklet, but also facilitate exchanges between dispossessed Q’eqchi’ communities and those where dispossession could still be prevented. Nonsensical acronyms being a pet peeve of mine, I suggested giving a Q’eqchi’ name to the project. Remembering the Q’eqchi’ practice of wrapping leftovers from a ceremonial meal into green leaves to carry home to share with elders and children, I asked Don Pablo, “How about calling it xeel?” He chuckled in agreement.

As Don Pablo’s subdirector, Rigoberto, elaborated to me by email, this term for ritual “leftovers,” xeel [pronounced sha-EL], resonated for him and in the communities because it is an important cultural “secret” (awas, sometimes translated as “taboo” but more appropriately understood as a tradition). “Our grandparents told us [on planting day] to make a large wrapping with two or three poch (fermented tamales) so that the family will have a satisfactory harvest with large cobs and with maize grains as large as a horse’s tooth.” Re-toasted on the clay griddle back at home, the leftover maize has a special, savory odor, and though you may have already eaten your fill, you are hungry yet again. Again, xeel refers to the green leaves that are used for making the tamales and that are re-distributed to wrap up food leftovers to take home (See Figure 3).

As a custom deeply tied to planting, the concept of xeel apparently sparked deep conversations in ACDIP’s member villages in the 150+ meetings they organized over the next year with funds from IAF. At these gatherings, villagers spontaneously began reflecting on how to make more productive the lands they have left, a.k.a. the “leftovers.” As James C. Scott (1976, 11) once famously argued, “It was the smallness of what was left rather than the amount taken (the two are obviously related, but by no means identical) that moved peasants to rebel.” In this case, it was an agro-ecological rebellion from below. Communities expressed a hunger for more information on agroforestry, revitalization of heirloom maize, tree canopy crops like cacao orchards, home gardens, mulches, natural pesticides, intercropping, biochar, nitrogen-fixing cover crops, and other forms of organic agriculture and reforestation. In a dramatic shift of concern from land rights to land use, they asked ACDIP’s leadership for agroecology education programs for their youth, so they might have a future in farming. They also noted they were weary of flight-by-night development processes. As Rigoberto Tec related to me, community leaders began asserting, “We don’t want any more projects.” Rejecting the bandaids of neoliberal charity, they wanted autonomy. From cadastre crisis emerged a new vision for reconstituting a transgenerational and self-governing commons.

With a Q2.6 million (about US $300K) settlement from a 2012 racial discrimination lawsuit, ACDIP’s leaders built a high school and then somehow figured out how to add educational accreditation to their organizing portfolio as peasant leaders. Even without furniture, books, or other basic equipment, they inaugurated the school in July 2019 with an incoming class of 50 young men and women (evenly divided), with plans to expand to 500. While holding fast to the cultural promises in the Peace Accord on Identity and the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, they also insist that the state cannot abdicate its responsibility for education, health, and other aspects of integrated development. Having secured permanent state funds to pay teachers, the school will provide Q’eqchi’ youth with accredited degrees in integrated agrarian development including practical and conceptual training in agroecology, traditional medicine, rural trades, and apprenticeship with elders. In turn, the youth promise to return to support village autonomy and learn from their elders.

From Leftovers to Autonomy

In work plans for 2014, ACDIP described mostly “old” peasant concerns like “promotion of a technical commission (mesa) to create a land legalization protocol for the whole department of Petén,” by 2015, autonomy had clearly become the central organizational focus. Their annual donor PowerPoint shows a dramatically reformulated institutional mission to “promot[e] consciousness for land defense and territory of the Indigenous Communities of the Q’eqchi’ Maya people and recovery of principles, values, ancestral cultures and Maya worldview (cosmovisión).” Other aspirations included, “defense of indigenous peoples in their lands, territories, natural resources, and food sovereignty, thinking not only in the present but also in future generations.” Insofar as other traditional agrarian issues were mentioned, they were reframed “for good living” (para el buen vivir).

Even with this rapid rhetorical evolution, the reality is that as a peasant federation, ACDIP’s leadership still tirelessly responds to human rights threats and titling problems in their member communities. As noted in donor reports, many of ACDIP’s base communities face “intimidation, persecution, threats from either the palm companies, narco-ranchers, political parties, and municipal mayors who attempt to disarticulate the indigenous and peasant struggle.”5 I, therefore, suggested allocating some funds in the final budget of our grant proposal to retain a lawyer as a small protective measure against nefarious interests. Forgoing personal protection, ACDIP’s leaders instead employed his expert advice to test an innovative, territorial defense strategy adapted and applied by other Maya peoples across Guatemala (Peláez 2014). As Rigoberto Tec wrote to me, “rather than constantly putting out fires, we want to develop creative legal strategies within the framework of [Guatemala’s] agrarian laws.”

Peláez’s legal strategy for declaring autonomous indigenous communities springs from the fundamental right to self-identification first articulated in the 1989 International Labor Organization’s Convention 169 (ratified by Guatemala in 1996) and further enshrined by the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). Guatemala’s Constitution also recognizes indigenous lifeways, customs, traditions, and forms of social organization (emphasis mine) in Article 66. Although virtually impossible to constitute communal lands at a national level, the municipality lends space to indigenous law, dating back to structures of indirect rule from the colonial period. Based on article 20 of the Municipal Code, customary legal structures can be enshrined in mayorial books. To avoid political cooptation of indigenous councils represented, Peláez (2014) brilliantly recommends that leaders not permit the municipal registrar to treat them as another analog of secular administration (like the community development councils or COCODES or other neighbor associations). Nor do they need to prove standardized or written by-laws or western leadership structures (presidents, etc.) because indigenous communities have maintained ancestral law that is prior to state formation.

Following a couple of test cases in 2013 and 2014, by 2016, ACDIP successfully secured municipal registration for their first eleven villages as “autonomous indigenous communities.” Having also simultaneously secured a representative seat on the municipal development council, ACDIP celebrated in a press release these “principles of intercultural and participatory democracy” and pride that “today, yes, we feel like we have been taken into account” (“que hoy sí nos sentimos tomados en cuenta”). This illustrates that the move towards autonomy is not an abdication of Guatemalan citizenship nor the right to state support for education, health, and other social services, but to interpolate those rights through ancestral authorities. As Ramiro Tox commented to Woodfill (2019, 90) in a region south of Petén that has a similar process of self-determined development underway, “We do not need to wait for the municipal government to come and develop our communities, because we can do it ourselves.”

By 2019, 44 of their member villages have been reconstituted as “autonomous indigenous communities.” Moreover, they have brokered space with nearly half the municipalities in the region (in San Luis [21], Sayaxché [15], Poptún [3], La Libertad [2] and San Francisco [1]), creating a precedent for another 69 or so declarations in process. As the oldest region of Q’eqchi’ settlement in Petén, as well as the birthplace of several of ACDIP’s core leaders, San Luis elders are now leading the next steps for cultural revitalization to reconstitute communal lands.6

Following lawyer Peláez’s (2014) advice, ACDIP’s communities follow formalities of colonial origin (seals and tax registration) that cannot be avoided but place them under opaque structures of elder-facilitated consensus. Having repeatedly suffered the trickery of paperwork, indigenous communities are rightly preoccupied with official record keeping. Beyond the wooden staffs given to the spiritual elders, each autonomous village has a ledger for meeting minutes that continue to be written in [a] long-hand colonial style. Perhaps most importantly, they have the legal standing to title land collectively and govern project budgets.

Leadership

Resistance movements may absorb and replicate the hierarchies of the systems they replace, but they also may give new meaning to those hegemonic structures. Much as “closed corporate communities” used municipal structures to maintain indigenous forms of leadership in the colonial era (Wolf 1957), ACDIP found a creative space in the neoliberal present in which to reconstitute traditional forms of leadership to heal villages torn asunder by land grabs, religious factionalism, militarized leadership, cooptation from extractive industries, and competition among development organizations. The Spanish brought with them a heavy tradition of Roman legalism, delegating tax collection responsibilities to indigenous mayors, civic-religious cargo systems, and labor contractors (corregidores), but also certain judicial powers (Restall, Sous, and Terraciano 2005). The internal structure chosen to govern the autonomous communities is essentially a de-Catholicized cargo system composed of:

a council of usually four spiritual guides,

undergirded and accountable to the wisdom of the ancestral authorities (the eldest of elders), and

articulated to the external world by a bi-lingual political representative who acts merely as a spokesperson.

All other village committees will be subsumed under and coordinate through the cargo leadership. ACDIP itself may apply these principles to their own leadership. Rather than continuing with the western-imposed structure of president, vice-president, secretary, treasurer, and at-large members, in their next assembly, they plan to establish a more culturally-appropriate “cargo” system at the regional level.

For centuries, in their negotiations with the Spanish colonial system, indigenous peoples chose bi-literate, bi-cultural mayors or caciques (often themselves descendants of pre-Colombian nobility) to negotiate their local interests. Over time, this evolved into a Mayan notion of leadership that eschews vanguardism. Shaped by fundamental values of egalitarianism, in Q’eqchi’ communities, leaders merely represent the voice of the people. A leader might “open a road,” (aj k’amok b’e) but should never impose ideas on the masses. Leaders are ultimately spokespeople, not ambassadors. In turn, community members are said to walk “behind” (chirix), yet pushing their leaders forward, as reflected in this photo chosen for ACDIP’s website (see Figure 4).

From a distance, I worried if these new leadership structures might exacerbate pre-existing factionalism based on age, religion, political parties, and military alignment that shaped kinship and social dynamics in all the villages where I conducted fieldwork. (I could, for example, trace divisions between cacao growers and cattle ranching families in Jaguarwood back a generation to religious divisions described in Schackt’s [1983] ethnographically rich thesis on factionalism in that same village.) Although Catholic communities predominate among the autonomous indigenous villages, the revival of time-worn leadership structures is resonating even among evangelicals, perhaps in part because a key ACDIP organizer himself was a lifelong Baptist preacher. A new cohort of Q’eqchi’ spiritual guides are themselves rejecting Christianity (whether Catholicism or Protestantism) and removing ceremonial elements perceived as colonial. In the region just south of Petén, Woodfill (2019, 211) also describes how a combination of ceremonial revival and reinvention are circumventing the Catholic-evangelical divide. As a leader, Tomás, told Woodfill, ceremony is “not religion; it is culture.”

In other ways, the re-establishment of customary governance was actually easier done than said. While prior Maya organizing has resulted in the displacement of elder authority (Wilson 1991), ACDIP’s turn towards autonomy seems to have healed generational divides. In one of ACDIP’s first autonomous communities where I had the opportunity to participate in a 24-hour meeting/ceremony, elder authority was stronger than I had ever witnessed elsewhere. The young men played the marimba till their hands were blistered and bloodied; not until the presiding elder gave the word to rest at four a.m. did their melodies pause. At the same time, I was struck by the ardent participation of a team of three young men as notarial scribes and evident interest of young women observing the elder female spiritual guides. In many ways, the system has created more space for elder women to exercise their traditional influence. Having always lived with extended families during fieldwork, I have witnessed many a Q’eqchi’ man being scolded, supported, or transformed by his wife’s or mother’s opinion-especially not to sell land. While gender issues remain a zone of contention within ACDIP’s elected board, at the village level, Q’eqchi’ women’s influence has anecdotally slowed the rate of land sales-the exact degree to which we hope to capture by another participatory mapping project in 2020.

In other ways, both male and female elder councils are already rising to the need for conflict resolution and restorative justice. Narrated with pride and adrenaline from a hard day’s work before our August 2019 meeting, Don Pablo described to me how via his cell phone, he had saved the life of a Q’eqchi’ peasant. Having missed the bus into town to sell a sack of corn, the farmer had hired a young motorcyclist to transport him. Meeting up later, the farmer realized the young man was drunk and decided to return home alone by bus. The young motorcyclist continued drinking and had a fatal accident on the road back. His father was furious and instigated a crowd to extradite the frightened farmer. Following Don Pablo’s suggestion, the council of spiritual guides in this autonomous village assembled a meeting and were able to calm the dead boy’s father. Meanwhile, a delegation went to town to file testimony of the farmer’s innocence at multiple government offices (for human rights, the attorney general, etc.). A lynching was averted.

Land Reclamation

Beyond conflict resolution, customary governance only truly flourishes in reciprocal relationship with territory, as theorized by Maori jurist, CF Black (2010), “the land is the source of the law.” In this, westerners have long misunderstood communal land governance as “communism.” As I have explored elsewhere, commons are not resources but processes (Grandia 2012). In Q’eqchi’ communities, agricultural land may be planted in groups through reciprocal labor exchange, but the harvest belongs to the family that assembled the labor. What is communal about the system is that as a collective, a community decides who plants where and when. The land ultimately belongs to the mountain spirits, the tzuultaq’a. Humans can only ask usufruct permission for its use.

Where land disputes in a few regions of Petén prevented private titling, ACDIP is pursuing the opportunity to reconstitute dozens of villages with fully-fleshed communal tenure. However, most of their member communities were channeled into private allotments during the colonization period. After decades of subdivision and land sales to outsiders, these villages are a patchwork of tiny fields interspersed by many absentee owners. Here a reconstitution of “communality” would mean that henceforth, Q’eqchi’ landowners would have to seek the permission of the community before selling their parcel to outsiders. He or she would have to give first purchase preference to another community member or allow the community itself to put the land in common. Following dreams and instruction from their elders, ACDIP’s leadership eventually hopes to buy back sacred sites lost to land grabs, possibly via carbon-sequestration funding.

From their deeper experiences as peasant organizers, however, they are cautious about cooptation, about becoming “project people” (proyectistas). By necessity, they have mastered the awkward art of the “logical framework” and Gantt charts, quarterly reporting, and other complexities of accounting systems imposed by donors. Yet, ACDIP’s leaders are keenly aware that “their communities don’t want anymore to do with NGOs.” As a social movement, they nevertheless do need and deserve some money for basic operations - for computers, bus fare, meeting rooms, food, etc. Following Chayanovian principles of “belt-tightening,” during hard times when salaries run out, they return to their villages to plant. Like a union, member communities pay an annual quota that sustains many of the fundamental expenses.

Reflecting the self-reliance that is a core value of Q’eqchi’ autonomy, as the six-year IAF funding drew to a close, with no maudlin fanfare, they closed their rather ugly rented office to work off-grid from the high school instead. Internet access was a dispensable luxury; cellphones are sufficient. Never once have I heard them complain of working relentless nights, weekends, all-night ceremonies, long workshops, all holidays, or maintaining cellphone touch with their base communities amidst the COVID pandemic. As Pablo said, “A leader doesn’t count the days” (Un líder no cuenta los días). Ergo, one of my roles in my own uncounted academic weekends is to help them spin their accomplishments in terms legible to donors, without permitting the temptations of money to circumscribe their sprawling agenda for autonomy. If, under classic liberalism, the quintessential agent of discipline is a panoptic state penitentiary, under neoliberalism it is perhaps more the self-censoring, self-imprisonment of a professionalized NGO with watered-down projects palatable to donors (Hale 2002, 496).

Conclusion

As a manner of conclusion, I thus end with an anecdote about how ACDIP’s organizers maintain their still sutured identities as indigenous-peasant-community organizers. Impressed by what she had learned from me about ACDIP’s accomplishments, a high profile NGO friend generously offered to help them with strategic planning. As she began prescribing advice to condense their nine platforms to three programmatic areas, I saw a look of unease, if not alarm in their eyes. Their strength lies in the intentional fluidity and flexibility of their work. A “lost” day spent resolving a lynching builds a constituency for the next phase of work. Undercutting crude Marxist dichotomies between the cultural and political-economic sphere, they juggle a broad organizing repertoire that reflects the plural and hybrid realities of being indigenous small farmers in a globalized economy, including but not limited to these nine points:

Integrated rural development

Identity rights as indigenous peoples

Right to land

Food security and sovereignty

Youth and children

Gender/women

Interculturality

Territorial defense

Training and capacity

Education

Organizational strengthening

To simplify and make fully legible their aspirations would leave them vulnerable to cooptation. Ergo, they skillfully asked my NGO friend instead to help convene another meeting of spiritual guides to discuss agrarian strategy late into the night over liquor and dreams, rather than her offer for western-centric strategic planning by daylight.

Academic publications must draw to an end, but indigenous movements continue evolving. At best, we can capture a conjunctural snapshot of the complex, heterogeneous, opportunistic, and sometimes contradictory organization of social movements. At this particular moment, what is perhaps most remarkable about ACDIP’s declaration of 44+ autonomous villages is that no one in the professional class of nonprofit and state technicians in my networks seemed to know about it. The praxis of autonomy is a quiet process meant to deflect the colonizers’ attention. As a people who have historically found resilience in decentralization, flight, refuge, and opacity, perhaps this should not be surprising. After all, autonomy itself translates only awkwardly to Q’eqchi’ as “the people looking after the community self” -junesal ib’, li kaleb’aaleb’ naril rib’ se’ junesal richb’en xkomon. While the upward struggles against neoliberalism continue, as an association, they have chosen to spend time reflecting inward to rebuild culturally-appropriate education for their youth, resolve disputes through ancestral values of balance and reciprocity, subsume secular committees to the elder councils, and teach agroecological practices to restore the leftover lands that remain. Though scholars tend to be deductively preoccupied with how theories of autonomy translate into practice, perhaps the more genuine question is how practice inductively constructs the concept. Mare tzacal.