Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Científica General José María Córdova

Print version ISSN 1900-6586

Rev. Cient. Gen. José María Córdova vol.10 no.10 Bogotá Jan. 2012

Lawfare: The Colombian Case*

Guerra jurídica: el caso colombiano

La guerre juridique: le cas colombien

Guerra jurídica: o caso colombiano

Juan Manuel Padillaa

* Researche monograph originally presented to the School of Advanced Military Studies of the United States Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavevenworth, Kansas, approved for Public Release.

a Máster en Seguridad y Defensa Nacional, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College. Director de la Escuela Militar de Cadetes "General José María Córdova", Bogotá, Colombia. Comentarios a: juan.padilla@esmic.edu.co

Recibido: 20 de Febrero de 2012. • Aceptado: 15 de Abril de 2012.

Abstract

The terrorist groups in Colombia have applied Mao's theory of protracted people's war, seeking to use all available means of struggle to achieve their revolutionary goals by counteracting govemment policy. One way that Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC), Ejército de Liberacion Nacional (ELN), and illegal paramilitaries confront the nation is the use of 'lawfare' defined as the opposing force's use of the national and intemational judicial systems to achieve victory and legitimacy when they cannot challenge the government militarily. Terrorist groups have skillfully infiltrated the Colombian judicial system, and are utilizing the both nationallegal institutions and the intemational law system against the government. They have received support for their struggle from various agents and organizations within the society that, intentionally or unintentionally, are serving their interests.

This paper provides a holistic understanding of this complex situation currentIy taking place in Colombia, shows how FARC and ELN are using lawfare in the context of the protracted people's war as a tool to challenge the government, and offers an starting point to examine altematives to deny the terrorist groups the ability to utilize the judicial system to achieve their political goals.

Keywords: Lawfare in the Colombian judicial system, ELN, FARC, terrorist groups in Colombia.

Resumen

Los grupos terroristas en Colombia han aplicado la teoría de Mao de la guerra popular prolongada, tratando de utilizar todos los medios disponibles de lucha para lograr sus objetivos revolucionarios de contrarrestar la política de gobiemo. Una manera en que Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC), el Ejército de la Liberación Nacional (ELN) y grupos paramilitares ilegales confrontan a la nación es el uso de la "guerra jurídica" que se define como el uso por parte de fuerzas de oposición de sistemas judiciales nacionales e intemacionales, para lograr la victoria y ganar legitimidad, por cuanto no pueden enfrentar militarmente al gobierno. Los grupos terroristas se han infiltrado hábilmente en el sistema judicial colombiano, y están haciendo uso tanto de instituciones legales nationales como del sistema de derecho intemacional, para ir en contra del gobierno. Han recibido apoyo para su lucha de distintos agentes y organizaciones al interior de la sociedad que intencionalmente o no, están sirviendo a sus intereses.

En el presente artículo, donde se presenta una comprensión holística de esta compleja situación que actualmente tiene lugar en Colombia, se muestra cómo las FARC y el ELN están utilizando la guerra jurídica en el contexto de la guerra popular prolongada, como una herramienta para desafiar al gobierno, y ofrece un punto de partida para examinar altern ativas de solución que permitan frenar la capacidad de los grupos terroristas de utilizar el sistema judicial para el logro de sus objetivos políticos.

Palabras clave: Guerra jurídica del sistema judicial colombiano, ELN, FARC, grupos terroristas en Colombia.

Résumé

Les groupes terroristes en Colombie ont appliqué la théorie de Mao de la guerre populaire prolongée, cherchant à utiliser tous les moyens disponibles de lutte pour atteindre leurs objectifs révolutionnaires pour affronter la politique gouvernementale. C'est une façon comme les Forces armées révolutionnaires de Colombie (FARC), l'armée de libération nationale ELN, et les groupes paramilitaires illégaux confrontent la nation. Bien qu'ils utilisent comme forme principale la «guerre juridique», qui est définie comme l'usage abusif des systèmes judiciaires nationaux et intemationaux par les forces opposées pour remporter la victoire et s'assurer une légitimité, lorsqu'ils ne peuvent pas rivaliser militairement avec les forces de l'État. Les groupes terroristes parviennent à s›infiltrer habilement dans le système judiciaire colombien, et ils ont également la possibilité d›utiliser un certain nombre d›institutions du système juridique, dans l›ordre interne comme dans l›ordre international, pour s›opposer au gouvernement. Dans leur lutte, ils ont eu le soutien de divers agents et organisations au sein de la société qui, intentionnellement ou non intentionnellement servent leurs intérêts propres.

Cet article, que présente une compréhension holistique de cette situation complexe qui se passe actuellement en Colombie, montre comment les FARC et l'ELN appellent le lawfare, ce «guerre juridique» qu'ils utilisent dans le contexte de la guerre populaire prolongée de Mao comme une méthode pour défier le gouvernement. L'article fournit aussi un point de départ pour examiner des solutions alternatives qui réduirait la capacité des groupes terroristes d'utiliser le droit comme arme de guerre pour atteindre leurs objectifs politiques.

Mots-clés: Lawfare («guerre juridique») dans le système judiciaire colombien, l'armée de libération nationale ELN, Forces armées révolutionnaires de Colombie (FARC), groupes terroristes en Colombie.

Resumo

Os grupos terroristas na Colômbia têm aplicado a teoria de Mao da guerra popular prolongada, tentando usar todos os meios de luta para conseguir seus objetivos revolucionários a fim de combater a política do Governo. Uma maneira que as Forças Armadas Revolucionárias da Colômbia (FARC), o Exército de Libertação Nacional (ELN) e os grupos paramilitares ilegais utilizam para enfrentar a nação é o uso de "guerra jurídica". Esta é definida como o uso da força de oposição dos sistemas judiciais nacionais e intemacionais, para conseguir a vitória e ganhar legitimidade, pois eles não podem enfrentar militarmente o governo. Os grupos terroristas infiltraram-se habilmente no sistema judiciário colombiano, e agora estão fazendo uso dessas instituições nacionais legais e também do sistema de Direito Internacional para ir contra o governo. Esses grupos receberam apoio de diferentes organizações e agentes de dentro da sociedade para suas lutas que, intencionalmente ou não, servem aos seus interesses. Este trabalho, apresenta uma compreensão holística dessa situação complexa, em curso na Colômbia, e mostra como as FARC e o ELN estão usando a guerra jurídica no contexto da guerra popular prolongada como uma ferramenta para desafiar o governo. Fornece também um ponto de partida para examinar soluções alternativas que reduzam a capacidade desses grupos terroristas de usar o sistema judiciário para alcançar seus objetivos políticos.

Palavras-chave: Guerra jurídica do sistema judiciário colombiano, ELN, FARC, grupos terroristas na Colômbia.

Introducction

Unquestionably, victory or defeat in war is determined mainly by the military, political, economic and natural conditions on both sides. However, not by these alone. It is also determined by each side's subjective ability in directing the war.

MaoTseTung (1936, 190-191)

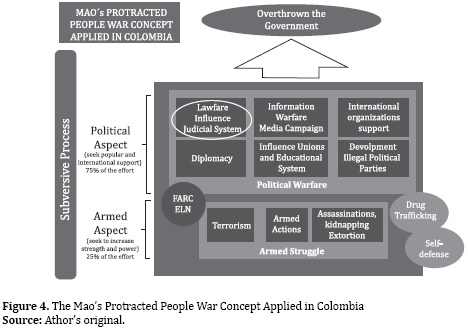

For almost six decades, a broad mix of violent actors has created conflict in Colombia, resulting in terrible consequences that jeopardize the country's process of democratic consolidation. Throughout this time, the insurgents in Colombia have applied Mao's theory of protracted people's war, seeking to use all available means of struggle to achieve their political goals and to counteract government policy (Tse Tung, 1936, 225). Lately, the Neo-Marxist narco-terrorist groups Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) and the Ejercito de Liberacion Nacional (ELN), the main insurgent groups, and even the illegal paramilitaries, have employed a new means to confront the Colombian government through a form of political warfare. In this new method, known as "lawfare," insurgents exploit the national and the international judicial systems to achieve victory and legitimacy through means other than direct military opposition. Insurgents have skillfully utilized the judicial system, state institutions, and public laws to further their cause against the Colombian government. They have received support from various agents and organizations within the Colombian society that, intentionally or unintentionally, are serving the insurgents' interests (Dunlap, 2001, 11).

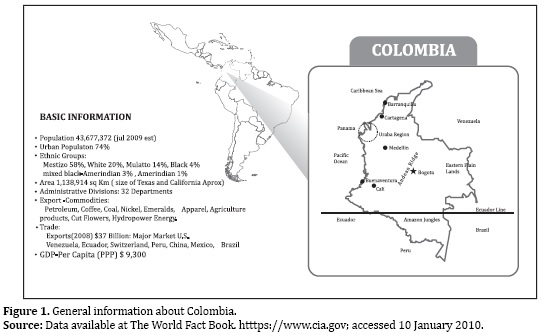

Analysis of the complex situation in Colombia, a country the size of Texas and California combined, demonstrates the existence and extent of the ongoing subversive processes insurgents employ, including the use of lawfare as an important tool to challenge the government in the context of a protracted people's war. A description of the background and context of the current situation in Colombia, supported by demonstration of the employment of lawfare in two case studies, supports several recommendations for neutralizing insurgents' ability to exploit Colombia'g judicial systems to achieve their goals.

The situation in Colombia serves as a cautionary note for nations that rely on sophisticated itnd complex legal systems. These nations must remain vigilant to prevent exploitation of such systems by opposition groups hoping to bring about national insecurity and hamstring otherwise-Iaudable national security efforts.

1. Background

Today's Colombian conflict began in 1948 with a bloody period called "la Violencia," a bipartisan confrontation following the assassination of the populist Liberal candidate for the Presidency, Jorge Eliecer Gaitan. In the 1960s, the rise of intemational communism enabled the establishment of the FARC as an armed wing of the Colomian Communist Party. Similarly, the success of the Cuban Revolution and Che Guevara's foquismo theory inspired the formation of the ELN in 1966. Over the next two decades, these Cominunist groups slowly expanded their ranks, while seeking control of the Colombian government (Safford & Palacios, 345-347).

Major changes occurred in the late 1980s and the early 1990s when the FARC and the ELN lost financial and logistic support from the world' s failing Communist regimes. The fall of the Berlin Wall and the Soviet Union's ,collapse weakened Nicaraguan and Cuban capability to support Colombian insurgents, forcing them to either collaborate with or fight drug traffickers to obtain the necessary resources to maintain their illegal armed structures. As a result, a new actor and different phenomenon joined the conflict. Drug-traffickers and landowners formed self defense groups or Autodensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC), also known as paramilitaries, to counter insurgents' kidnapping and extortion. Since the early 1990s, both insurgents and selfdefense groups have gradually eliminated and displaced drug traffickers, obtaining control of most of the illegal trade (Fernandez, 2005, 12).

Terrorism emerged in the 1990s as a powerful psychological weapon used by both insurgents and paramilitaries to intimidate the population. Illegal groups committed atrocities with increasing frequency during this decade, inc1uding kidnappings, murders, massacres, bombings, and destruction of villages, pipelines, and energy towers in an attempt to gain control over various regions of the country. The FARC and the ELN, undeterred by a peace process developed under the former President Andres Pastrana administration, gained nearly 25,000 members in the 1990s due to profits from drug trafficking. The govemment led peace negotiations lasted almost four years, from 1998 to 2002, and as part of their conciliatory efforts, the government provided the FARC a forty two thousand square kilometer demilitarized zone (about the size of Switzerland). This merely resulted in an increase of FARC's and ELN's financial streIlgthand illegal recruitment, with no longterm reduction jn terrorist or insurgent activity (Fernandez, op. cit., p. 1).

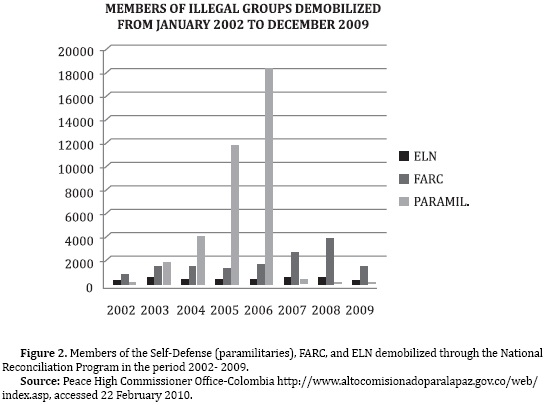

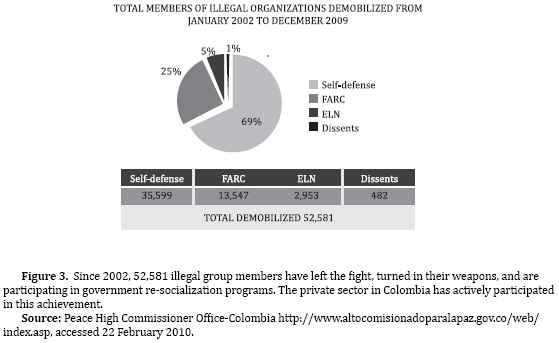

The government's successful passage in 2002 of President Alvaro Uribe's Democratic Security Policy complemented the ongoing 'Plan Colombia' started by his predecessor in 1999, and changed the context of the conflict. Since then, Colombia has employed a comprehensive national strategy that has effectively weakened the terrorist groups and enabled the government to regain control of territory (Cf. Democratic Security and Defense Policy and Plan Colombia)1. Through this strategy, the government forced the AUC to demobilize, and led the FARC and the ELN to conduct a self-described 'strategic withdrawal'.

Today the FARC is in the worst situation it has experienced in its long history. In the last eight years, the state has inflicted severe and decisive blows to this organization in the political, military and intemational arena, leaving it farther than it has been in decades from achieving its objectives. In 2008, the FARC lost of three of the seven, members of its Secretariat, the highestlevel command and control of the organization. These los ses incIuded Manuel Marulanda, historicalleader of the organization, and Raul Reyes, leader of FARC political and intemational strategy, severely degrading the organization's effectiveness. The Armed Forces have drastically reduced FARC's sources of income-primarily drug trafficking, kidnapping, and extortioncausing a significant decrease in the availability of resources necessary to keep running its operations and logistical activities. Currently FARC completely lacks the popular support essential to achieving its goals (Galula, 2005, 71). In fact, in 2008 an enormous majority of Colombians publicly rejected the FARC in mass demonstrations2. The reduction in the number of its members has seriously affected FARC's combat capability. In just slightlymore than two years, between January 2006 and May 2008, FARC lost 17,274 of its members to demobilization, captures, and casualties, lowering the morale of its remaining members in spite of rigorous indoctrination (Santos, 2-6).

Despite these setbacks, FARC remains far from defeated. Rather, it has adapted by necessity to its new circumstances. The most important factor that allows and encourages the FARC to continue its struggle is that it still controls significant economic resources, mostly derived from drug trafficking, that enable it to survive and to keep supporting its 8,000-member organization (Schoen & Rowan, 2009, p. 10)3. However, the difficulty of achieving success in the armed struggle has forced them more than ever to turn to the polítical and international arenas to continue their fight. The sympathy FARC has engendered among sorne leftist organizations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and membersof the intemational community has further increased its military and financial strength, providing the organization both the resources and will necessary to continue its fight (Santos, op. cit., 340).

2. Framing the Nature of the Colombian Conflict

During the last twenty years, the conflict in Colombia has changed enormously because of multiple internal and external factors, the prevailing geopolitical situation, and the transformation of society itself. All of these aspects make it difficult to clearly define the nature of the conflict and identify its root causes. Complicating matters, the nature of conflict in Colombia varies depending on who defines it. Therefore, six key groups-insurgents, paramilitaries, left-wing parties, Colombian citizens, the international community, and the Colombian government -each have their own unique perspective on the conflict (Clavijo & Clavijo, Jr., 2006, 36).

Colombian insurgent organizations generally view conflict as a war on behalf of the proletariat, declaring war on the state and combining all forms of warfare in order to impose a more egalitarian socialist system. The paramilitaries believe the conflict is a war against the FARC and the ELN, one they must fight due to the inability of the state security institutions to protect the population. Colombian left-wing parties have a romantic view of the conflict, seeing it as a confrontation led by guerrillas who seek to achieve social fairness by using all forms of struggle against an oppressive state, while supporting paramilitary groups that systematically violate human rights4.

Most of the Colombian populace views the conflict as an armed confrontation by narcoguerrillas seeking to overthrow the state, with non-state sanctioned paramilitaries fighting the guerrillas and drug-trafficking organizations funding both illegal groups. Even a clear majority of the international community appears misinformed by media bias and the lack of knowledge regarding the entanglements of interests that exist within the conflict. Those living abroad tend to see the struggle in Colombia as a confrontation between political and armed guerrillas seeking to achieve democracy and social advances against an elite ruling class (Clavijo & Clavijo, Jr., op. cit., 37). However, there is wide range of viewpoints among the populace and the international community about the ongoing situation in the country5.

The Colombian government views the situation as a terrorist threat coming from insurgents and illegal paramilitary groups, both financed by drug traffickers, who seek to subvert the national order and replace the existing regime with one sympathetic to their interests. Often, the government publicly denies the existence of an armed conflict. On January 31, 2004, in a speech to the diplomatic corps accredited in Bogotá, President Alvaro Uribe stated, "In Colombia we have a respectable rule of law in permanent improvement, a committed multiparty democracy, and that gives us the right to call terrorist threat an armed opposition; there is no armed conflict in Colombia, we are under a permanent terrorist threat." President Uribe has reaffirmed this statement on several occasions since then (Restrepo, 2005).

While the various actors' perspectives of the conflict differ, they share the view that armed confrontation exists, and the drug traffickers provide financial support to the illegal opposition factions. However, none of the prevailing views recognizes the significance of the non-violent aspect of the conflict, and its effectiveness in attacking the structure of the state and its legitimate institutions from within. Therefore, in reality, the scope of the conflict is much broader than commonly perceived. In addition to armed conflict, the political, social, diplomatic, economic, military, and legal arenas all have bearing on the nature of the conflict.

A holistic examination reveals that the internal Colombian conflict is a clash in which the state is defending its democratic institutions from the subversive influence of a variety of actors. The terrorist groups (FARC and ELN) aim to seize power, political legitimacy, and strength. The paramilitaries intend to fill the vacuum left by the legitimate state authority where it lacks strength. The drug traffickers financing this process have spread their operations into different regions of Colombia to expand their illegal activities. In this context, terrorism is a weapon of illegal armed groups, drug trafficking is the source of funding, and political warfare is the main instrument in the subversive process (ibid., p. 41).

Therefore, one must understand the internal conflict in a broader manner in order to examine and address the increasing use of state and legal institutions to substantiate insurgent political positions within Colombian mainstream society. General Adolfo Clavijo, former Director of the Universidad Nueva Granada in Bogotá, argues that due to the methodology and the instruments employed, this aggression is political warfare, typically occurring in the form of evident conspiracies against the state (ibid., p. 41).

The debate regarding the definition of the conflict does not reduce its significance. Conceptual clarity in understanding the nature of the conflict is important for profound practical reasons. In the first place, the terminology used to define the nature of the conflict is essential to understanding its complexity and will thus determine the range of possibilities for finding a possible solution. Secondly, this terminology has a bearing on the country's formal relations with the international community that can leverage important decisions regarding the conflict in Colombia, its society, and its economic development. In addition, the application of international law has traditionally been determined by the manner in which conflicts are defined and classified. For all of these reasons, the definition of the conflict and the various views of the actors involved significantly impact public opinion, which is essential in providing legitimacy and strength to the government (Posada, 2002, 5).

3. Democratic Fragility and Political Warfare

The existence of systematic aggression against the rule of law undertaken through political warfare is a complementary activity of the armed struggle, mainly conducted by insurgent groups with the goal of undermining the legal institutions and structures of the nation. Different levels of government fail to understand comprehensively the threat these methods pose to state institutions. Political warfare, once considered nonexistent or undamaging, especially by the state officials, has in fact caused much more damage to society than physical violence. Political warfare is part of the subversive process that seeks to stifle the nation. Practitioners of political warfare disguise their actions as legitimate instruments of the democratic process, when in reality they represent a Marxist challenge to democracy's fundamental convictions. Those who undertake political warfare embed their efforts so effectively within existing political and democratic processes that they usually go unnoticed.

Colombia possesses the oldest democracy in Latin America; it is transparent and seeks consolidation after many years of internal unrest6. By contrast, as General Clavijo points out, political warfare "Is hidden and vague; it insistently demands the application of democratic principles; it appears to be their advocate, and does so in a manner that seems to be reliable. However, whenever possible it misinforms, slanders, coerces, and pressures improperly; it infiltrates and undermines the state using all forms of struggle." Furthermore, according to General Clavijo, its practitioners enjoy protection both inside and outside of the state, with significant help from the international community (Clavijo, 2002, 13).

In this sense, Jean Francois Revel in his book How Democracies Perish explains:

Democracy tends to ignore, even deny, threats to its existence because it loathes doing what is needed to counter them.... It awakens only when the danger becomes deadly, imminent, evident. By then, either there is too little time left for it to save itself, or the price of survival has become crushingly high.... What we end up with in what is conventionally called Western society is a topsy-turvy situation in which those seeking to destroy democracy appear to be fighting for legitimate aims, while its defenders are pictured as repressive reactionaries.

Revel, 1984, 7.

Thus, threats to democracy hide behind a level of deception so effective even true democrats fail to recognize them. The system under attack unintentionally protects its assailants and facilitates their actions due to its inability to recognize the threat. Revel explains that democracy is the first form of government in history to blame itself because another system is attempting to destroy it.

"It is the humility with which democracy is not only consenting to its own obliteration, but it's contriving to legitimize its deadliest enemy's victory" (Revel, op. cit., 8).

Although political warfare did not explicitly receive its name until the twentieth century, its methods date back to ancient times, and the foremost military theorists have analyzed it. In the fourth century B.C., Sun Tzu warned, "the skillful leader subdues the enemy's troops without any fighting... he overthrows their kingdom without lengthy operations in the field." (Sun Tzu, 2009, 129-136). Carl von Clausewitz, in On War, stressed the relationship between war and policy, making clear the need to consider war as an organic whole combining both political and military actions. Thus, Clausewitz contended, "The political object -the original motive of the war- will thus determine both the military objective to be reached and the amount of effort it requires" (Clausewitz, 1976, 81).

Today's political warfare traces its roots to Marxist and Maoist ideology. Marx, in his second manifesto addressed to the members of the International Association of Workers of Europe and the United States in September 1880, stated, "History teaches us all. It is with nations as with individuals. To deprive them of all attacking means, you must remove all means of defense. Do not just put your hands around his neck." Lenin argued for the application of Marxism-Leninism in the development of the political war through a massive propaganda apparatus. In this manner, Marxist revolutionaries seek to prevent the nation from using its power and resources to counter their gains (Clavijo, Adolfo, Ed., 2009, 16).

In the early twentieth century, Mao Tse Tung developed a concept of political warfare that insurgents have applied successfully in a number of recent and ongoing conflicts across the globe. Mao articulated the integration of Marxism and Leninism, the handling of the population, and the use of political propaganda as a unified approach that he called "protracted people's war." Mao asserted, "Men and politics, rather than weapons and economics are the determining factors in the war." According to Bard O'Neal, this concept is "... undoubtedly the most conceptually elaborate and perhaps the most widely copied insurgent strategy" (O'Neal, 1990, p. 49). Maoist theory of protracted war, which China employed against both Japan and Kuomintang, consists of three sequential phases, each of which differs with respect to the correlation of forces. The first phase is the strategic defensive, in which the insurgents must employ a low use of violence while concentrating on survival and developing a viable political organization. Once the insurgents begin to achieve military victories and gain popular support, they enter the second phase, in which they seek to achieve strategic stalemate by conducting guerrilla warfare. The third phase, strategic offensive, begins when the insurgency's victories enable an escalation of conflict that produces demoralization and defection of the government's troops. In this final stage, insurgents conduct mobile conventional attacks on a large scale, and the political and psychological effects of these attacks build on the success of earlier insurgent efforts to cause the collapse of the government (O'Neil, op. cit., 49-51). According to Rangel (2008, p. 63) most theorists that have studied the Colombian conflict agreed that after FARC's struggle reached the second phase in the period between 1996 and 1998, they regressed to the previous phase of strategic defensive with the withdrawal to what they call the "strategic rear," located mostly in the Amazon jungles of Colombia and in the jungles of some neighbor countries.

4. Political Warfare in Colombia

Although the insurgent groups in Colombia now widely known as narco-terrorists cause a damaging economic dispute by using the illegal drug trade as their main source of funding, they have an active political presence that the Colombian government cannot ignore. In the 1990s, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Colombian Communist Party divorced itself from the FARC. As a result, the FARC Secretariat illegally created the Clandestine Communist Party of Colombia (PC3), which became the primary political front of the FARC. This clandestine organization has taken great strides to reorganize the proletariat in the cities and the peasantry in rural areas (O'Neil, op. cit., p. 50-55).

Despite the rejection of the Colombian government, FARC, PC3, and ELN are part of international political organizations like the Sao Pablo Forum - a group consisting of the majority of the leftist political parties and unions in Latin America - and the Movimiento Continental Bolivariano. The Sao Pablo Forum (SPF) is a political organization that brings together nearly every leftist organization in Iberian America, including armed guerrilla movements. Its name comes from the Brazilian city where its first meeting was held. The members of the SPF use social unrest as a way to grow and to fortify themselves, using new and varied forms of struggle. The SPF member-organizations include the ELN and the FARC, the Alternative Democratic Pole in Colombia (a left-wing political party), the Workers' Party of Brazil, the Broad Front in Uruguay, the Socialist Party of Chile, United Left of Peru, the Free Bolivia Movement and the Socialist Movement of Bolivia, the Ecuadorian Socialist Party, the United Socialist Party of Venezuela - PSUV, the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) in Mexico, the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) in El Salvador, the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) in Nicaragua, the Guatemalan National Revolutionary Unit (URNG), the Democratic Revolutionary Party of Panama, the Lavalas Movement of Haiti, and every communist party in the region, including the one in Cuba. A number of Latin American heads of state are members of the SPF; namely, Lula da Silva, Raúl Castro, Hugo Chávez, Tabaré Vásquez, Evo Morales, Rafael Correa, Daniel Ortega, and René Preval. The Movimiento Continental Bolivariano, which has its head office in Caracas, Venezuela, is an international movement created to provide international and political support to the FARC; currently Alfonso Cano, FARCs new leader is its honorary president (Mejía-Azuero, 2008, 9).

Through these political affiliations, FARC, ELN, and PC3 are seeking political recognition and belligerent status. FARC and ELN have long sought belligerent status, hoping to leverage the combatant privileges that this legal category would provide. Furthermore, their political affiliations lead to international relationships with other states or organizations that offer the possibility of eliminating their terrorist image. In accordance with the LOAC, an insurgent group gains belligerent status when all of the following conditions occur: it controls territory in the state against which it is rebelling; it declares independence from the state (if its goal is secession); it has well-organized armed forces; it conducts permanent hostilities against the government; and, importantly, the government recognizes it as a belligerent actor. Neither the FARC nor the ELN have achieved all these conditions (Allison & Goldman, Belligerent Status).

One of the greatest achievements that the FARC and, to a lesser degree, the ELN have reached through political warfare is that only 31 countries in the international community, the United States and the European Union members among them, and only two in Latin America (Colombia and Peru), have labeled them as terrorist organizations. This provides FARC and ELN personnel significant freedom of movement in the region, enabling them to shift resources between countries and actively participation in various political organizations (U.S. Department of State, Terrorist Designation List).

General Clavijo effectively synthesized the nature of political warfare in Colombia, explaining how it has permeated most sectors of the society:

Simultaneously with the armed conflict, an underground war that is not seen on the surface is taking place and has been one of the main factors contributing to the political success of the insurgency in Colombia. It is a war neither with weapons nor uniforms, without regular or irregular combat formations, with no deaths or injuries ... is a war being waged both within our own borders and abroad... a fight that is being waged from desks, international forums and organizations... waged from our own political, economic, legal, diplomatic and social institutions... In short is a war that has touched the hearts of national and international opinion to tip the scales in favor of the terrorist insurgency that does not stop at anything and has left in its tragic power a stamp of blood and pain.

Clavijo, 2002, 207.

The actions the FARC and ELN undertake against the nation and society demonstrate the articulation and application of political warfare. According to Mao's concept, armed action is subordinate to the political struggle.

It is important to distinguish between revolutionary warfare and political warfare. Revolutionary war consists of armed struggle and is usually associated with the removal of a colonial regime. In revolutionary warfare, the rebels attempt to destroy a political-ideological system and replace it with another one. Revolutionaries' objectives overlap with those of political warfare, but the difference lies in the intensity and employment of the components and actors that support both. On the other hand, political warfare relies on deception, sophistry, and socioeconomic inequity, attributing political blame to democracies that fail to obtain the common well-being, and seeking to gain legitimacy by using collective will to fight on behalf of the people.

The lethality of this combination is to produce social mobilization and seizure of state control. In the case of the FARC, the clandestine national guerrilla conference forms the nexus of confrontation and enables the insurgents' planning process. The FARC holds these conferences randomly when security conditions allow part of its Secretariat and good number of guerrilla leaders to gather. The organization held its eighth conference in April 1993 and its ninth in January 2007, both in Colombia's southern jungles (Mejia-Ferrero, 2008, p. 12). For decades, military intelligence has struggled to know when and where the next FARC national guerrilla conference would happen. Since 1964, they have made nine of these strategic planning meetings, 1964, 1966, 1969, 1971, 1974, 1978, 1982, 1993 and 2007.

During these meetings the organization analyzed, evaluated, and synchronized its objectives and actions. At the end of this process, the conference conclusions become the guidelines for the years to follow. At the ninth conference, the organization updated its basic guidelines, reinitiating political and armed struggle against the state. The FARC's leadership made it clear that as part of adhering to political warfare, the organization should develop intelligence, mass support, diplomatic advantage, and the ability to exploit the legal system in conjunction with military actions. The FARC's Secretariat considers that coordination in each of these fields can enable them to regain the political and armed initiative lost during the last eight years (FARC's Ninth Conference: Conclusions).

5. Lawfare

Lawfare is a concept increasingly discussed in government, academia, and media circles worldwide. According to Dunlap (2008), the term 'lawfare' seems to have first appeared in the manuscript Whither Goeth the Law (Carlson & Yeomans, 1975). It is an emerging concept that describes a method of warfare in which an individual or opposition group exploits the legal system as a means to achieve military objectives. Rather than seeking victory on the battlefield, challengers attempt to destroy the enemy's will to fight by undermining the popular support that a democracy requires to maintain effective governance and employ military power. In an attempt to weaken public and international support, opposition forces portray the government's legitimate military actions as unfair or immoral violations of the spirit of law. There are many different forms of lawfare, but the one progressively gaining popularity among democracy's opponents is the "cynical manipulation of the rule of law and the humanitarian values that it represents" (Dunlap, 2001, 11).

The United States, Israel, and many other democracies in the world face similar challenges to Colombia's in dealing with this relatively new threat. Major General Charles Dunlap, the Deputy Judge Advocate General of the United States Air Force, defines lawfare as "the strategy of using -or misusing- law as a substitute for traditional military means to achieve" (Dunlap, 2008, p. 146). His observation of the execution of military campaigns in twenty-first century conflicts in which the enemy employs lawfare, leads him to ask several important questions: "Is warfare turning into lawfare? Is international law undercutting the ability of the U.S. to conduct effective military interventions? Is it becoming a vehicle to exploit American values in ways that actually increase risks to civilians? In short, is law becoming more of the problem in modern war instead of part of the solution?" Increasingly, experts answer these questions in the affirmative, and argue that the increasing role that law is playing in the conduct of military campaigns is not only unprecedented, but could potentially constrain democracies from waging decisive war (Dunlap, 2001, 4).

The logical use of lawfare in this sense has a solid basis in the concept of Clausewitz's trinity, in which the power synergistically produced by the government, the military, and the people must be in balance if success is to be achieved in war. Traditionally, the western approach to achieve victory that humanitarian law endorses focuses on diminishing enemies' military strength. However, challengers increasingly seek to unbalance their adversaries' trinity by focusing their efforts against the people, thereby seeking to diminish the legitimacy of their opponent's actions by eroding popular support for the military effort (Dunlap, 2001, 11; Clausewitz, 1976, 89).

Ironically, it was the long-standing desire of the international community to use law in order to prevent war, or at least to make it as humane as possible, which enabled the rise of international law around the globe. Today the LOAC, based on the Geneva Convention of 1949, is the most recognized legal statute worldwide and represents western ethical values that attempt to limit the adverse effects of war, especially among noncombatants. Law of armed conflict (also referred as international humanitarian law) is the branch of international law applicable to armed conflicts. LOAC restricts the methods and scope of warfare through a set of universal laws (treaties and customs) that limit the effects of armed conflict and that protect civilians and persons who are no longer participating in hostilities (Dunlap, 2001, 7).

Nevertheless, some international lawyers like David Rivkin and Lee Casey have expressed concern about emerging international law, which they argue is profoundly undemocratic and even has the potential to undermine the legitimacy of democracy. Many of these international laws, which possess the potential for universal application, contain unrealistic norms making them susceptible to misinterpretation. The result is that these new international laws often degrade states' ability to employ military means to deal with threats to their legitimacy and sovereignty. Rivkin and Casey argue, "If trends of international law are allowed to mature into binding rules, international law may become one of the most potent weapons ever deployed against the United States." Some may argue they overreach with this conclusion, but Rivkin and Casey make a convincing argument. Opponents of democracy will not waste the opportunity to exploit democratic values and institutions in attempts to weaken them and achieve their goals. They will do so without any concern for LOAC. Even more, international law may well make the world safe for aggressors by imposing excessive constraints on those countries that are willing to use force to prevent and punish them (Rivkin & Lee, The Rocky Shoals of International Law).

Sometimes just the perception of LOAC violations can have a significant impact in the execution of further operations. Major General Dunlap argues the Gulf War (1990, 1991) provides two clear examples of situations where no LOAC violation occurred, but the mere perception that the United States and its coalition partners had violated the LOAC resulted in tremendous military consequences for future operations. The first was the attack against Al Firdos bunker in Baghdad, a site assessed by coalition intelligence analysts to be key to the Iraqi command and control structure. The pictures released to the media after the attack, which showed the bodies of Iraq officials' family members being dug out from the ruins (they had used the bunker as a bomb shelter), achieved politically what the Iraqi defenses forces could not do militarily. Coalition leaders decreed downtown Baghdad off limits as a target location for the rest of the campaign to avoid repetition of this type of scene. A comparable situation occurred when images of hundreds of burnt vehicles along the so-called "Highway of Death," destroyed by an air attack against retreating Iraqi forces, caused fear that the resulting popular outcry could harm the solidarity of the coalition. These media factors influenced the coalition decision to end the campaign early, allowing Saddam Hussein to reconstitute most of his Republican Guard. Future challengers of democratic nations learned from these cases that they could capitalize on collateral damage incidents by releasing evidence to the popular media that would make their enemy seem insensitive to LOAC and lacking respect for human rights (Dunlap, 2008, 147).

The current situation facing Israeli officials provides another example of an intensive lawfare campaign undertaken in order to isolate the state. Throughout the Western countries, Israel's opponents have taken aggressive actions in order to obtain the arrest of military and political officials traveling abroad. The origins of this campaign can be traced back to the U.N. World Conference Against Racism, held in South Africa in 2001. A forum of NGOs drafted a "Declaration and Programme for Action" which declared Israel a "racist state," engaged in "crimes against humanity." The declaration called on the attendees to seek the "immediate enforcement of international humanitarian law ... to investigate and bring to justice those who may be guilty of war crimes, acts of genocide ... that have been or continue to be perpetrated in Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories" (Siskind, 2010).

The attempts to arrest Israeli officials is based on legal instruments known as "universal jurisdiction" which acknowledge that some criminal conduct is so grave that it affects the fundamental interests of the international community as a whole. Most Western legal systems recognize the concept of universal jurisdiction. Lawfare practitioners target Israel officials who have participated in actions such the recent incursions into Gaza to bring to an end the rocket attacks on Israeli communities. They claim that these actions constitute war crimes, and they initiate legal actions to investigate and prosecute Israeli participants. Based on the universal jurisdiction doctrine, NGOs have filed lawsuits in many European countries and the United States. They have been particularly active in England where last year a court issued an arrest warrant for former Foreign Minister Tzipi Livni, forcing her to cancel her trip to the United Kingdom. In early January 2010, an Israeli military delegation canceled a trip after their British Army counterparts informed them that they could be arrested in the airport upon their arrival. Hamas, supported by some well-known NGOs, has established a committee of legal specialists to collect information of alleged war crimes in support of charges against Israeli officials in Belgium, Switzerland, Denmark, Holland, the United Kingdom, Spain, and the United States. Diya al-Din Madhoun, head of the Hamas legal effort, declared to the Times of London in December 2009 that lawfare in these forms "has absolutely become our policy" (Hider, Hamas using English law to demand arrest of Israeli leaders for war crimes; Siskind, 2010, p. 3). Command, was commanding operations on July 23, 2002, when 15 people died after a 1,000-kilo bomb was dropped over Gaza City. When Almog, now retired, flew to London, he discovered at the airport that an arrest warrant for war crimes had been issued against him. Major General Almong never left the aircraft, and returned to Israel without incident.

Hamas employs rocket and mortar attack against Israel not only to threaten its population, but also in order to provoke a response. Hamas continues these attacks until they have inflicted a sufficient level of pain to provoke Israeli retaliation. This retaliation normally employs massive force, inevitably resulting in the death of civilians and destruction of their homes and other non-military locations, since the Israeli response targets the source of the attacks, which are normally civilian-populated areas. The resulting loss of civilian life provides Hamas and their supporters with evidence enabling them to file suits in various courts around the world, disrupting Israeli international relations and increasing Israel's sense of isolation (Siskind, op. cit., p. 4). According to Goldstein & Meyer (2009), the decision made in 2004 by the International Court of Justice declaring Israel's security fence a crime against humanity, which ignored the fact that the fence contributed to reduce terrorist attacks, is considered another example of lawfare.

Colombia's former Defense Minister Juan Manuel Santos, the Armed Forces commander, the former Army commander, and the Police Director are all dealing with a situation similar to that of Foreign Minister Tzipi Livni . Currently they are the subjects of a criminal investigation in Ecuador, a nation that does not consider the FARC a terrorist organization, over the cross-border bombing of a FARC camp in 2008 that killed the FARC's second-in-command, Raul Reyes, and 25 other terrorists. An Ecuadorean judge from Sucumbios issued an arrest and extradition order for the Ministry, and three generals asked Interpol to intervene in order to bring the officials to court. After political tensions that lasted several weeks, Ecuador's National Court of Justice turned down the orders, but the investigation is still ongoing (El Tiempo Newspaper, Denunciar a Juez Ecuatoriano que Condeno a Juan Manuel Santos estudia el Gobierno).

Lawfare can also operate as a positive instrument of the state. In order to reduce the destructiveness of war, in ideal situations lawfare methods can replace military means in order to produce a desired effect. In particular, General Dunlap argues for law-oriented, effects-based operations' potential effectiveness, especially in a counterinsurgency environment. For example, the United States established the Rule of Law Complex in Baghdad as an important element of the American campaign plan. A law and order task force staffed by judge advocates supports this complex, with the mission to provide a safe environment for carrying out police and judicial functions, enabling Iraqis to resolve their problems and find solutions within an effective legal system. After completing a tour of duty in Iraq, U.S. Army Reserve Colonel Linsey Graham, who is also a U.S. senator, stated, "building a fair legal system that holds all segments of the population accountable is one way to kill the insurgents beyond (using) military force" (Dunlap, 2008, 147).

Another similar example is the Justice Houses program established by Colombia's Ministry of Justice, with the support of USAID. This program, created in 2002, provides indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities unprecedented access to justice that was previously unavailable to them because they live in remote communities where FARC used to have a strong influenced in the late 1990s. The Justice Houses program promotes efficient, comprehensive, and peaceful resolution of everyday legal issues. Fifty-four Justice Houses located in many different communities handled 1,424,287 cases in 2009 and more than 9.4 million total cases since the inception of the program. This is a successful example of an alternative dispute resolution method based on strengthening the rule of law, thereby causing a positive effect among the population (Marcella, 2009; Ministerio del Interior y Justicia, Servicio Nacional de Estadisticas).

6. Judicial War and Juridical War: distinction in the context of Lawfare

Lawfare is also a relevant topic among Colombian academics, writers, journalists, militaries, and government officials. Jean Carlo Mejía Azuero, dean of the faculty of law at the Nueva Granada University in Bogotá, argues that lawfare "... is the use of the norms of a state or the international community in order to obtain psychological victories. To be implemented, it raises the incursion or infiltration of the legislative production sites and the legislative, judiciary, public administration and control institutions." The meaning of lawfare, once merely a tool of protracted peoples' war, has evolved as its employment has expanded, making it one of the primary tools of political warfare. Lawfare, Mejia says, creates a regulatory framework that can potentially serve contrary to the state's interests. One example is the elimination of exceptional measures to counter terrorism; a development that occurred when the Colombian Congress repealed the Anti-Terrorist Statute in 2004. This act had provided legal tools to Colombian security forces, including expedited procedures within the judicial system that saved government time, money, and other resources required to process and try individuals accused of terrorist acts in court. Despite the severity of the current terrorist threat in Colombia, the congress repealed this statute on the basis that it exhibited possible excesses of authority, and its application provided a window of opportunity for human rights transgressions against the terrorist defendants (Mejía-Azuero, 2008, 27-29).

Mejia raises an important distinction regarding this issue, arguing that the law must differentiate between juridical and judicial war. Juridical war is the practical outcome of the regulatory framework, the legislation. Judicial war takes place on domestic or international legal sites; in other words, in courts and tribunals (Mejía-Azuero, 28).

An examination of the international establishment can clarify this distinction. Colombia is a signatory member of the Statute of Rome, which established the International Criminal Court (ICC), and contributed to the Pact of San Jose and the creation of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights7. The ICC has jurisdiction to prosecute individuals subject to international public law. It possesses the authority to try individuals from signatory countries, including members of their security forces. This court has therefore become the battlefield of the judicial war, as its verdicts are the result of debates centered on judicial issues. On the other hand, the Inter- American Commission of Human Rights and the newly established Human Rights Council of the United Nations Organization are typical stages where juridical war takes place, because these courts create legal acts and regulations. As Mejia points out, in legal terms, "Judicial war is the variety, and juridical war is the gender" (ibid., p. 28). Thus, lawfare can have two manifestations. The juridical manifestation reveals itself in the new laws that seek to prevent and fight the subversive process and terrorist actions. The judicial manifestation occurs when members of state security agencies face charges brought before the court by insurgent and terrorist collaborators in order to prosecute them unfairly, thereby limiting their ability to perform their official duties (ibid., 28-29).

7. Lawfare and the Judicial System in Colombia

In this context, lawfare is an essential element of political warfare as seen in Figure 4. In the ongoing conflict in Colombia, the threat gains strength through litigation while jeopardizing the legal protections Colombian citizens enjoy by abusing of the rule of law.

The fundamental goal of the Colombian state is to ensure the sovereignty of the entire territory, and to guarantee life and property of its citizens with absolute respect for human rights. To achieve this goal, the state requires effective interaction from all branches of government. The most important of all branches in this sense is justice. Without a robust, efficient, and independent judicial system that maintains the confidence of all citizens, the populace could perceive the state as lacking legitimacy. Seeking just this goal, subversive elements in Colombia have learned to attack the justice system, making it one of the victims of the conflict while simultaneously using it as a weapon against those who defend the state institutions (Clavijo & Clavijo, Jr., 2006, 19).

Piero Calamadrei, the famous Italian author of The Eulogy of Judges, stated, "Judges have a deadly power to make right the injustice, to force the majesty of law to become the champion of unreason, and print indelibly on the candid innocence the bloody stigma that will confuse it with crime forever." The administering of justice is a difficult task because the verdict and the truth must match. Calamadrei added, "The judge must leave his own political opinions, religious faith, economic status, regional traditions, and even his prejudices and phobias". Therefore, judges must remain focused on the primary goal of seeking out the truth, no matter their personal beliefs and biases, seeking to determine right from wrong in accordance with the laws governing Colombia (Calamadrei, 1946, cited by Rafael Nieto in the Prologue of Clavijo & Clavijo, Jr., 2006, 12-13).

The judicial system is now a permanent target of those opposed to the Colombian rule of law. This opposition interferes with the proper performance of judicial duties, particularly when intimidation causes judges to forego unbiased fairness and make flawed judgments, rather than decisions based solely on truth revealed in a fair evaluation of the facts of each case. As a consequence of the conflict, this branch of public power does not enjoy the full freedom to act based on the law, making evident the fact that it is impossible to shield it from external interference (Clavijo & Clavijo, Jr., op. cit., 51-53).

Many years of conflict in Colombia have caused the population and the nation's institutions to have a high regard for human rights and a corresponding intolerance for abuse or collateral damage during military operations. Terrorists take advantage of the Colombian sensitivity for human rights by exploiting the judicial system to eliminate the capable armed forces leadership through intimidation and bribery, often forcing people to make false charges anonymously against government officials. At the same time, both insurgents and paramilitaries blame others for the human rights abuses and crimes they have perpetrated. Even Jose Manuel Vivanco, director of Human Rights Watch, has expressed his disillusionment with the challenge Colombia faces in defeating insurgents and paramilitaries who are capable of employing lawfare to subvert government efforts: "We come to the conclusion that they're using humanitarian law as just part of a public relations campaign." If international law is to remain a valuable tool in conflicts like that experienced by Colombia, the government must implement measures to prevent practitioners of lawfare from exploiting the judicial system to serve their unjust purposes (Jose Manuel Vivanco, as quoted by Forero, 2001).

It is true that in the course of the conflict, some members of the security forces have committed excesses and even crimes. Judges have decided the fate of such individuals in accordance with the law, eventually resulting in convictions of those responsible for the crimes. Any attempt to prevent the abuses of lawfare must not result in a lack of accountability for government officials and security forces. However, a large number of complaints brought before the courts lack sufficient evidence, and yet the cases go forward, calling into question the trustworthiness of the judicial institutions and its members (Clavijo & Clavijo, Jr., op. cit., 24).

Only rarely do judiciary and governmental institutions and the legislative branch appear to recognize that the administration of justice is facing improper interference. Rather, corrupt or intimidated individuals often support allegations of the existence of plots leading to judgments based on bias rather than truth and justice. When individuals come forward with accusations of authorities or government officials involved in human rights abuses or crimes, the courts often take the complaint for granted a priori. If the trial ends in a conviction, authorities consider that they have acted fairly. On the other hand, even if the verdict is an acquittal, the defendant often suffers irreversible damage to his reputation because observers who assume the initial complaint was true see him thereafter as a villain (ibid., 14).

Therefore, within the administration of justice there is a current struggle between two antagonists: one serving the petty interests of a subversive process, and the other altruistically seeking to act in accordance with its responsibility for impartial judgment. Ideally, the correct application of judicial codes would be the undisputed winner in this contest, while the unjust influence should have no role in the legal process. Nevertheless, this is not the case, and on many occasions, the complexity of the instruction process governing legal procedures results in their entanglement, leading to flawed verdicts. This situation is a consequence of the nature of the conflict, the actions of the protagonists who interfere with the judicial processes, and the economic interests at stake, represented by the millions of dollars in compensation payments allocated annually by the state (Posada, 2002; Clavijo & Clavijo, Jr., op. cit., 13).

The two case studies presented in a next section will widen the understanding of the situation in Colombia regarding the issue.

8. Organization of Justice in Colombia

Security and the rule of law are the start points for any discussion about governance in a democratic society like Colombia's. However, these start points are besieged by threats that can undermine their development. Democracy is unsustainable without security and security is unattainable without the rule of law. Although security is important, state influence to achieve social and economic progress is just as important in establishing authority. Yet, it is the rule of law that binds them all together. Rule of law generates legitimacy, which the Command of the Armed Forces in Colombia considers one of the nation's centers of gravity in the ongoing conflict. It also maintains the collective will of state and society in order to make possible the state monopoly of use of force, stability measures, equal rights, and social order (Ospina, 2009, Smith, 2003, p. 275; Marcella, 2009, 2).

The judiciary is the primary branch that supports the rule of law. The judiciary is a complex organization that includes four high courts: the Constitutional Court, the Supreme Court of Justice, the Council of State, and the Superior Judicial Council, which all have different roles, responsibilities, and functions. The Supreme Court of Justice oversees the administration of the judiciary and has responsibility for determining whether to try cases involving members of the security forces in civilian or military courts. The major drawback is that no clear hierarchical structure exists within the Colombian court system. Therefore, no court is considered the highest. The division of labor among the courts should solve this friction, however sometimes the legal boundaries are not clear enough to avoid tensions in matters concerning appropriate jurisdiction or constitutional interpretation.

Roman law serves as the foundational base of the Colombian judicial system. The Spanish Empire adopted Roman law, which led to its integration into Spain's Latin-American colonies. Building on this existing foundation, the new Political Constitution of 1991 extensively revised the judicial system8. It established an independent prosecution system, the position of Attorney General, and a people's defender office to investigate human rights cases. These judicial system reforms did not produce the expected results.The reforms introduced by the 1991 Constitution failed in several significant areas. Court case congestion remained high, courts still faced significant backlogs, and the resolution conflict index had not improved significantly. Overall, the system remained far from having the agility required. By the late 1990s, the increased levels of dysfunction within the judicial system indicated the need for deeper reforms (Marcella, 25-26).

Strengthening the judicial system was one of the Democratic Security and Defense Policy pillars in order to strengths the nation's legitimacy. A first step towards addressing the dysfunction was the 2002 amending of the Constitution. This enabled structural reform of the judicial system to occur. Although it sustained the Spanish base law, it transformed the previous slow traditional investigation system to oral accusatory, the criminal code modelled on Anglo-American practice and procedures. The goal was to develop a new service model that improved the timeliness, quality, and the responsiveness to the citizens demands for court services. The U.S. Department of Justice and USAID played key roles in facilitating the transformation the court system required based on the legal framework of Plan Colombia. The implementation of judicial reform began in 2004 and was completed by 2008 (ibid.).

The contrast between the previous system, called civil law, and the new system, known as common law, is evident in several ways. In the civil law system, the investigation was controlled directly by a judge instead of a prosecutor. This allowed evidence and testimony normally presented in written form to be entered into the case with almost no opportunity for cross-examination by the parties. Additionally, there were no juries, participation by the prosecutor was minimal, and the trial was closed and based on documentary submission. In the accusatorial system, the parties control the investigation, the prosecutor assumes a more active role, and the judge serves as the neutral decision-maker. Additionally, evidence and testimony is presented orally in the court providing opportunity for cross-examination in public trials and jury trials are often called for to incorporate the society into the process (ibid., 28-29).

Perhaps this transition from a written and reserved system to this new oral, open and public process can improve the objectivity and effectiveness of justice. It also helps to prevent undue influence of those seeking political dividends of judicial decisions and recovers the spirit of law from who pretend to manipulate it. However, it is too soon to appreciate its impact in preventing lawfare (Fiscalía General de la Nación (General Prosecutor Office), Hablemos de la Justicia (Let's talk about Justice).

8. Military Justice

Colombian military justice has been the target of a "rupture process" since the 1980s, when it played an important role in dismantling terrorist organizations such as the Movimiento 19 de Abril (M19), FARC, ELN, and Quintin Lame. "Rupture process" is a term coined by French lawyer Jacques Verges in his book Judicial Strategies within Political Processes. Insurgents worldwide have studied and applied this concept since its publication in 1968 (Verges, 2008, 63; Clavijo & Clavijo, Jr., 2006, 279-283).

Verges explains that the concept applies to criminal processes with political connotation and consists of identifying and exploiting core contradictions inherent in criminal law to disarm the state by undermining its legal structure. It seeks to challenge not only the process itself, but also the current system that leads to the inversion of values, converting accused into accusers and disrupting the rules of justice. At this point, the circumstances of the criminal action recede to a secondary role and the attack against the state emerges as the main objective9.

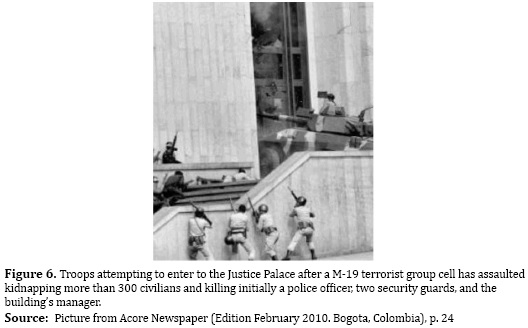

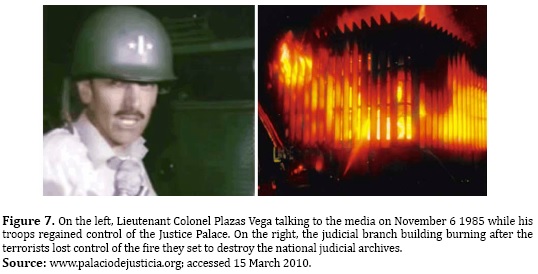

The M19 started applying Verges' rupture concept during the 1980s. Its members staged scandalous protests in prison against the system in charge of their judicial process: the military justice system. These protests, which were widely covered in the media, inspired other insurgent groups to undertake similar initiatives. Their efforts succeeded and new legislation eliminated the use of courts-martial proceedings against terrorists. It was the beginning of a methodical offensive aimed to reduce the state's ability to face terrorism and discredit the military judicial system in order to limit the application of its jurisdiction (Clavijo, Adolfo, Ed., 2002, 300-301).

Action against the Colombian military justice system has come from different entities, not only from the terrorist groups. Several NGOs, human rights activists, and state-adverse legislators have gradually weakened the military judicial system to the point that today its jurisdiction is limited to only very specific acts of military service. The government considers any suspected human rights violation unrelated to the military service, placing it under the jurisdiction of the Colombian civilian justice system. The government has limited the military's authority to investigate combat operations as well.

Cornelia Weiss, a lawyer in the U.S. Judge Advocate General's Corps (JAG) who has worked with the Colombian Ministry of Defense to help the military develop the legal resources to fight narco-terrorism, explains:

Colombian military must avoid any appearance that it defends and protects anyone who violates human rights. Soldiers who are alleged to have committed human rights violations are prosecuted in Colombian civilian criminal courts, not within the military justice system, and each death of a narco-terrorist guerrilla by a member of the Colombian military is investigated as a homicide. This sounds outrageous, but if an investigation doesn't occur, the Colombian military can't defend itself against accusations by human rights groups and guerrilla groups that an unlawful killing occurred.

Grace Renshaw, Oral Advocate.

In this sense, it is important to note that despite the conflict, Colombia lacks a legal framework that allows its own armed forces to conduct combat operations within its sovereign territory. The death of a terrorist group member in combat results in the initiation of an investigation for "homicide in combat". The unit involved must suspend its operations, isolate the scene, and wait for a judicial commission or members of the National Police's technical investigation group to investigate the facts.

Military members no longer possess the right of judgment by their own justice system. This resulted from human rights organizations and legislators arguing that military members adjudged by military courts can operate with impunity. However, military personnel believe they have the right for their cases to be heard by military judges who understand military doctrine and the uniqueness of combat situations. In their view, a civilian judge lacks that understanding.

Legislation in the Colombian Congress is changing the Colombian military justice system from an inquisitorial to an accusatorial system, as it did with the civilian justice system, in order to reduce processing times and legal costs, and increase efficiency. However, the jurisdiction of military justice currently remains limited to prosecute misdemeanors associated with the service (Renshaw, Oral Advocate, p. 1).

9. Non-Governmental Organizations

Non Governmental Organizations play a key role in the context of lawfare in Colombia. Like international corporations, NGOs are becoming major players in international relations. They have grown dramatically since the 1960s and continue to grow in number and in scope. NGOs have created a global network that connects people around the world, they have amassed an enormous consolidated budget, and their efforts to improve conditions in countries around the world continue to grow (Villar, 2006, 3).

The concept of NGOs is not entirely clear and may be is as extensive as its fields of action. They exist in a wide range of categories, including nonprofit organizations, opposition political groups, organizations in support of government initiatives or protection of social groups, and even corporations with business objectives. Some NGOs consist of thousands of members while others have as few as fifteen. NGOs' common feature is their emergence as a response to needs that the state does not satisfy. Societies have supported their creation and growth in their quest for alternative and complementary means to address the various shortcomings many involved in corrupt practices. The report reveals that the funds acquired through international channels are often misappropriated and misused, and sometimes have little impact on intended beneficiaries or on activities that the organizations claim to promote. Some NGOs, as discussed in the next section, even possess an ideology consistent with insurgent groups and actively serve their interests (ibid., p. 8).

10. Case Studies

Many cases exist that could illustrate the characteristics of lawfare in Colombia. The still unresolved San Jose and Justice Palace cases are particularly revealing not only because they demonstrate the use of law to obtain clear political military advantages, but also because of the national and international repercussions resulting from each case.

a. San Jose de Apartado - The Peace Communities

Daniel Sierra (whose name de guerre was "Samir"), the former second in command of the FARC's 5th Front, turned himself in to Colombian authorities in December 2008 in response to a national reconciliation program. His testimony provides a good understanding of how the FARC are applying both political warfare and lawfare as a means to confront the government. Samir was a member of the FARC for twenty-two years, serving in different fronts of the northwestern block10. In December 2009, in a press conference with other former FARC leaders and an interview with Mary O'Grady, editor of The Wall Street Journal, Samir explained the FARC's exploitation of civilians in zones designated by NGOs as "peace communities." He also stated that the so-called "peaceniks" that ran local NGOs were his allies and an important FARC tool in the effort to discredit the government, the police, and the military (O'Grady, 2009, 1).

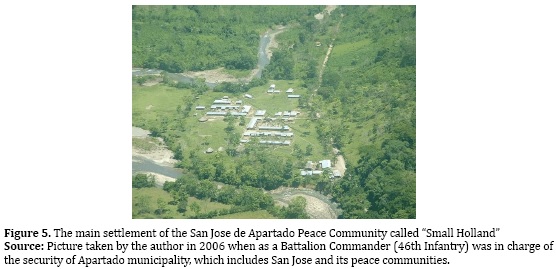

The 5th Front's area of influence includes San Jose de Apartado, a small town located in the northwest region of Colombia called Uraba where the violence in the late 1980s and the early 1990s reached the highest levels in the country. Control of this strategic corridor to Panama, the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific region is indispensable to international drug traffic. San Jose and the surrounding villages were designated a peace community in 1997 under a plan proposed by the local Catholic diocese11.

However, according to Samir the peace community of San Jose de Apartado remained far from neutral. Rather, he stated, the FARC had a close relationship with its leaders from the early days of its creation. In the interview, Samir said that the peace community was a FARC safe haven for wounded and sick insurgents and for storing all kinds of medical and food supplies. He also said that FARC suppliers met with rebels in the town, where five or six members of Peace Brigade International were always present. According to Samir, the peace community assisted the FARC in its effort to label the Colombian military as a violator of human rights. When the community was preparing to accuse someone of a human-rights transgression, Samir would 90 Local leaders undertook this initiative to create a place where civilians could live without fear of paramilitaries or guerrillas. They appointed the Colombian NGO Inter-ecclesiastical Justicia y Paz (IJP) to administer the initiative, which attempted to achieve full disarmament of all actors within the peace community, and rejected the presence of the police and the army. IJP enjoyed the backing of Amnesty International and the Peace Brigades International, two very active NGOs in Colombia, and established at least six similar peace communities in the Uraba region in the late 1990s, eventually challenging the sovereignty of the state in those areas12.

However, according to Samir the peace community of San Jose de Apartado remained far from neutral. Rather, he stated, the FARC had a close relationship with its leaders from the early days of its creation. In the interview, Samir said that the peace community was a FARC safe haven for wounded and sick insurgents and for storing all kinds of medical and food supplies. He also said that FARC suppliers met with rebels in the town, where five or six members of Peace Brigade International were always present. According to Samir, the peace community assisted the FARC in its effort to label the Colombian military as a violator of human rights. When the community was preparing to accuse someone of a human-rights transgression, Samir would organize the "witnesses" by ordering FARC members, masquerading as civilians, to give false testimony in judicial processes and in the media (O'Grady, 2009, p. 1).

The members of the peace community council and Samir's various supporters, including a Jesuit priest called Javier Giraldo who leads the IJP, and Gloria Cuartas, a former left-wing mayor of the municipality of Apartado (which includes the town of San Jose), insisted that the "peace" required that the military and police stay out of the area. Whenever an army or a police patrol came to San Jose or the surrounding villages, they denounced them in the media, claiming they interfered with the efforts of human rights organizations and NGOs and demonstrated a lack of respect for community "self determination." Nevertheless, the paramilitary groups refused to observe such accords. Samir states that when clashes between the FARC and the paramilitaries occurred, the peace community played a key role in shaping the story so that the public would blame government security forces for the resulting violence (ibid.).

Many such incidents occurred after the creation of the peace communities. In 2000, for instance, the paramilitaries stopped an ambulance evacuating a wounded female guerrilla and shot her. Samir says that the peace community claimed that she was a civilian member of its group and alleged that the army had killed her. Long judicial processes started in both the civilian and the military justice systems, which in the end concluded that no member of the army was involved in such incident and that the woman was a member of FARC. However, the had already caused irreparable damage to the army's image. The community also helped conceal FARC involvement in the region. In 2005, Samir says, the paramilitary killed a FARC rebel called Alejandro, but the peace community insisted that he was a civilian member from its group (Peña, 2).

Samir says he objected to the FARC's decision to get involved in drug trafficking, working with drug-running paramilitaries while concealing their activities behind the farcical peace communities, and exploiting the locals. In 2008, finally frustrated enough with the situation to act, Samir led resistance effort against FARC abuses, resulting in more than twenty-four villages breaking away from the peace community. His former leaders accused Samir of being an infiltrator, and the FARC Secretariat ordered him to be court-martialed. It was at that point that Samir decided to turn himself in and participate in the national reconciliation program (O'Grady, 2009, 1).

Samir verified during the press conference the compromise he made when he turned himself in: "I strongly apologize for what I did and I will work for reconciliation of the country. I will not give a step back." At the same time, he asked the Colombians to support his struggle in order to restore all the damage caused while in the FARC. Now he has become a spokesman for peace, persuading other insurgents to leave the fight (Santos, 2009, 182; O'Grady, 2009, 1).

Since then, the situation in Uraba has improved dramatically, the FARC is been substantially weakened, and normality has returned to the population. Nevertheless, the FARC still has influence and enough strength to cause damage in the area. O'Grady in her column wrote regarding Samir's testimony that "His adversaries accused him of making all this up to ingratiate himself with the government. But what cannot be denied is that while the FARC has been largely discredited among rural populations, it is the Colombian military, not the so-called peace community that has pacified Uraba and given new life to its inhabitants (ibid.).

Since September 2003, President Uribe has expressed his concerns about some human rights groups and NGOs acting as a front for terrorists13. Although many NGOs supporters in Colombia and abroad have rejected such claims, testimony provided by myriad of insurgents like Samir or Karina, the former 47th Front commander who was in the FARC for more than 24 years, that have abandoned the illegal groups, gives the government more evidences for this denunciation. These testimonies render evident links between the peace communities, the FARC and some NGOs that support them and confirm the way they are using the law to confront the state while exploiting the population (Santos, 2009, 186; O'Grady, 2009, 1).

b. Justice Palace - Colonel Alfonso Plazas Case