Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Científica General José María Córdova

Print version ISSN 1900-6586On-line version ISSN 2500-7645

Rev. Cient. Gen. José María Córdova vol.17 no.25 Bogotá Jan./Mar. 2019 Epub Nov 05, 2019

https://doi.org/10.21830/19006586.370

Justice and Human Rights

The incidence of private military and security companies on international humanitarian law

* https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9042-834X jonnathan.jimenez@esdegue.edu.co.

** https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6605-6846 juan.gil@esmic.edu.co. Escuela Militar de Cadetes “General José María Córdova”, Bogotá, Colombia.

*** https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4485-8845 henry.acosta@esdegue.edu.co Escuela Superior de Guerra “General Rafael Reyes Prieto”, Bogotá, Colombia.

Among the changes generated by the process of globalization of the 21st century to the military field is the emergence of new actors willing to provide the State with security services as an alternative in asymmetric warfare. These dynamics have prompted violations of human rights and international humanitarian law. This document critically and descriptively addresses the incidence of private military and security companies in these situations. This study reveals that the participation of 21st-century mercenaries in international, non-international and internationalized armed conflicts call into question the actions of the States because of their failure to assume the due international responsibility. A methodology of qualitative analysis with a descriptive approach was used in the research.

KEYWORDS: international humanitarian law; military mercenaries; Private security; State

Dentro de los cambios que trajo el proceso de globalización del siglo XXI para el campo militar, está la emergencia de nuevos actores dispuestos a prestar servicios de seguridad para el Estado como alternativa en confrontación de asimétricos. Estas dinámicas han propiciado violaciones a los derechos humanos y al derecho internacional humanitario. El presente documento aborda de manera crítica y descriptiva la incidencia de las empresas militares de seguridad privada en estas situaciones. En el estudio se evidencia que la participación de los mercenarios del siglo XXI en los conflictos armados internacionales, no internacionales e internacionalizados ponen en cuestión el accionar de los Estados, puesto que estos no asumen la debida responsabilidad internacional. En la investigación se empleó una metodología de análisis cualitativo con un enfoque descriptivo.

PALABRAS CLAVE: derecho internacional humanitario; Estado; mercenarios; militares; seguridad privada

Introduction

The 21st century marks the period of consolidation of globalization, a fact that has driven changes in cultural, economic, political, social, and military relations throughout the world. In the particular case of the military sphere, many of the wars currently waged are characterized by the confrontation between state actors and asymmetric actors. Thus, new dynamics of armed confrontation have been generated that have led to situations of human rights (HR) and international humanitarian law (IHL) violations.

In this new scenario, the international community is increasingly questioning the participation of States and their actions in international armed conflicts, and notably, non-international conflicts, given the emergence of new actors of a military nature willing to provide the nations with security services. These commercial dynamics strengthen the arms sector, which, in turn, favors a sizeable private military security industry specializing in armed conflicts, warlords who have gained prominence on the world stage, and whose actions significantly threaten the integrity of nationals of areas afflicted by conflict, without assuming any international responsibility.

It cannot be ignored that private military security companies (PMSCs) are a lucrative business model that generates employment and new economic opportunities around the world. However, given the slight or no-regulation followed by these companies their lack of adherence to responsible practices is widely known by the international community; this makes them an alternative in inflicting negative force, incurring in violations of HR and IHL (Comité Internacional de la Cruz Roja, 2006).

It should be noted that, unlike the people that make up the PMSCs, the members of the military forces of most countries, in their capacity as public servants, hence, guarantors of the rights and security of their nationals (as in the case of Colombia), develop activities that promote the free and full exercise of the populace's HR. It is understood that the defense of rights is not limited to the state's abstaining from violating them, but instead involves confronting the transgressors of such rights. Thus, the existence of armed forces is justified by the need to ensure -beyond the normative mandate- the fulfillment of such rights.

The ethical and moral paradox is that the profession of arms consists in being willing to risk life to defend the sovereignty, independence, and the integrity of the national territory and constitutional order. Now, the military forces' earnest activity to protect the populace responsibly and fully exercising HR is being carried out, throughout the world, by mercenaries contracted by PMSCs that lack these characteristics. The obligation of States to provide security should not be delegated to PMSCs; this grave error implies the violation of the rights that, allegedly, must be protected.

Since 2005, the UN established the United Nations Working Group on the Use of Mercenaries to analyze the use and participation of mercenaries, that is, foreign military experts in combat. As stated by Elzbieta Karska and Gabor Rona (Expertos de la ONU analizan aumento de mercenarios..., 2015) in a panel discussion organized in New York City, many of the mercenaries come from 80 nationalities and are guided by economic, ideological, and military interests. They are characterized by participating in armed conflicts, mostly in the Middle East and Asia. Approximately 20,000 mercenaries participate in armed conflicts in countries such as Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Syria, and Somalia.

Foreign individuals who come to exercise security functions within another territory lack legal structures to be prosecuted. It must be noted that the security companies that provide these services are, for the most part, in countries that have not recognized the international criminal jurisdiction or do not have existing treaties with the States where they provide their services. Therefore, they are exempt from liability in an eventual irrational use of force, a fact that can amount to serious violations of HR and IHL infractions.

These companies operate beyond the rules of IHL, the occupying force, and the contracting government; this creates a gray legal area that detaches them from any State and provides them a form of immunity, which easily translates into impunity. This situation implies that some States hire these companies to avoid direct legal responsibility. It must be noted that the transnational activity of security companies is dictated by economic criteria, not by the desire to enforce IHL.

Thus, the following question arises: What is the incidence of PMSCs on IHL? To answer this, we used a methodology of qualitative analysis with a descriptive research approach; it consisted of observing and describing the behavior of the object in question using the constructivist paradigm.

Methodology

A methodology of qualitative analysis with a descriptive research approach was used in this research, which consisted in observing and describing the behavior of the object in question. Three types of sources were used for the collection of information: primary, referring to official institutions; secondary, referring to articles and research reports; and tertiary, such as written and digital press. All this information was organized in databases according to the year of publication and the relevance to answer the research problem.

Conceptual approaches to IHL and mercenarism

The Hague Convention of 1907 on Neutral Powers established certain legal standards applicable to States and neutral persons in the event of war. However, it does not restrict the possibility for nationals of the Member States to work for the belligerent States (Convenios de Ginebra, 1907). Therefore, the national (individual) who was hired by a foreign power would not commit any international crime and should be treated as a soldier serving a foreign force. The reluctance to control the activity of individuals in the military field was based on the distinction of the early 20th century in which governments and individuals were considered exclusionary spheres.

This form of contract existed long before the formation of nation-states. During the Middle Ages, in the 9th to 15th centuries, in Europe, fiefdoms requiring the protection of large tracts of land were allowed to hire professional soldiers, a protection that the crown could not offer to all. According to Braidot (2011), there were paid soldiers and vassalage contracts, whose main purpose was to provide protection at a military level. Mercenarism reached such a high point that many of the paid soldiers were lent to monarchs in times of war. For example, the Castilian monarchy recognized the military service of the mercenaries offered to monarchs by the Navarrese Basques during the invasion of the Muslims, also called Moors, to the Iberian Peninsula (Douglas, 2001).

Not until the discovery of America, in 1492, was the need to professionalize a military corps raised. The first permanent professional armies were formed after the Peace of Westphalia (1648) with the establishment of nation-states, while, in parallel, the national identity was consolidated and the monopoly of the use of force was centralized, waning mercenarism little by little.

Although The Hague Convention of 1907 established that an individual's activity does not affect the activity of the State, this vision would gradually lose its rigor in subsequent decades when it became evident that the private actions of individuals could influence relations between States, above all, impact compliance with HR.

The next step in the regulation of private military actors occurred with the Geneva Conventions of 1949, especially with the III Geneva Convention (on the protection of prisoners of war). Its objective was to establish standards regarding the treatment of people who did not participate in hostile activities, such as civilians, health personnel, and members of humanitarian organizations and to the treatment of subjects who could not continue participating in combat, like the prisoners of war (Forster, 2004).

These additional agreements did not focus on controlling or prohibiting the activity of private military forces. In fact, the III Geneva Convention of 1949 only distinguished two categories: members of the armed forces (combatants) and civilian population, although Article 4 of this agreement includes the latter in the category of prisoners of war. These organizations never made a categorization, not even a formal distinction between mercenaries and other combatants (Fallah, 2006).

Concerning international humanitarian law, Protocol I of 1977, in the section entitled "Statute of Combatant and Prisoner of War," defines mercenaries as an autonomous category, distinct from combatants. Paradoxically, before the definition of mercenaries, and even in it, they are denied the status of combatant and prisoner of war.

Protocol I of Article 47 indicates that mercenaries will not be entitled to the status of combatant or prisoner of war and subsequently defines a series of characteristics describing the mercenary as 1) a recruited foreign local, hired to fight in an armed conflict; 2) taking part in hostilities and motivated by the desire to obtain a personal benefit according to a promise; 3) a non-national or resident of a party to the conflict; 4) not a member of the armed forces of a party to the conflict; and 5) not sent by an official mission as a member of its armed forces by a State that is not a party to the conflict (Preux, 1989).

Concerning human rights, it can be understood that public order should favor humankind, which is why it is up to the State to respect and protect without unlawfully attacking a person's inherent rights (Nikken, 1994). If the State maintains a monopoly on the use of force and is responsible for the actions and omissions of its security forces on people, why do security contractors not have international responsibility for the violation of HR and the breaches of IHL in conflict scenarios if a State contracts them?

First, it must be understood that there are some actors in the international system that are subject to public international law, which is why they are allowed to assume duties and obligations before the system and allowed the rest of the universal and inalienable rights. However, many of the actors in the international system do not possess this subjectivity, which prevents them from being recognized and recognizing other actors. According to the actor's reason and nature, recognition can be beneficial, as the actor assumes an active role, and has the possibility of being a recipient or beneficiary of any aid. On the other hand, the actor's omission or lawful action could take him or her before international instances without being judged by the national legal system. For example, the former Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) sought international recognition as belligerent actors of an internal armed conflict, international recognition that would have allowed them to receive help from another actor in the system, including a State (Jiménez, Acosta, and Múnera, 2017).

When contracted by a State, the PMSCs become civil contractors. In this sense, and depending on the nature of the conflict, PMSCs cannot receive the principle of distinction that allows them to be considered a target of attack. Despite this consideration, security companies must respect IHL. On the other hand, the UN recognizes the difficulties of categorizing PMSCs as a legal typology of the mercenary (Güell, 2010). In this regard, it can be stated that "it is not possible to classify PMSCs as combatants in strictu sensu, among other things because despite their eventual participation they are not part of the conflict, nor are they subject to a chain of command responsible for the conduct of their subordinates to that party" (Güell, 2010, p. 64).

Resolution 3314 (XXIX) of the General Assembly of the United Nations considers mercenarism as an illegal practice, as well as the formation of irregular groups sponsored by the State or that at least fight on its behalf. However, it does not establish that these practices, promoted by private companies, are illegal (Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas, 1974).

In this sense, two assessments can be established. The first assessment is the categorization of military security companies, which, because of their economic business nature, are not subject to international law and, consequently, lack direct international responsibility. The second assessment is the mercenary typology, which is not considered criminal and illegal behavior.

Accordingly, it can be affirmed that, in the event of a regulatory gap, IHL does not address the legality of PMSC activities nor does it establish responsibility for those who are part of them. As a paradox, the international legal definition of the actors called mercenaries, which operates in international law, does not deprive them of the right to prisoner of war status in the case of being captured. Mainly, Protocol I of 1977 provides the characteristics that an individual must meet to be considered mercenary and, in turn, be devoid of any legal guarantee.

PMSCs and mercenarism in the 21st century

Currently, Protocol I of 1977 and the International Convention against the Recruitment, Use, Financing, and Training of Mercenaries of 1989 provide the definition of mercenary. That is the extent of the legal regime of an activity that is propitiated by private actors not subject to Public International Law (PIL).

So why is it important to analyze the growing participation of PMSCs in armed conflicts and their impact on IHL? On the whole, the arms industry is one of the most lucrative businesses in the world. In equipment and military machinery alone, the five large defense companies (Lockheed Martin, Boeing, BAE Systems, Raytheon, and Northrop Grumman) recorded gains in 2016 for 150.925 million dollars (Barría, 2017), close to 53.8% of Colombia's gross domestic product for the same year (Banco Mundial, 2016).

PMSCs are among the wide range of arms trade options, companies providing security and defense services. For Sonia Güell, these organizations can be defined as "private, legally constituted companies that provide assistance services, advice or armed security, either as an alternative or as a complement to the regular armed forces that operate in areas that are in situations of armed conflict." (2011, p. 1). The alarming issue is the proliferation of these organizations, which turn the war into a business that can be highly commercialized without international legal restrictions, which calls into question the ethical and moral nature of the combatants who participate as paid soldiers of multinationals.

Principie of the military forces' exclusivity

In antiquity and during the Middle Ages, it was common for princes and feudal lords to appeal to armies of mercenaries that were given carte blanche, that is, a document authorizing the attack against potential or real enemies. However, when the transition from the medieval state to the modern state began -from the 15th century on- the function of guaranteeing the security and protection of the associates, until then diluted in the various feudal estates, was concentrated in the hands of a central authority. This is how permanent, institutionalized armies appeared, at the same time as the unification of the law and justice took place in the hands of courts and judges dependent on the same authority (Ábrego, 2013).

In this way, the satisfaction of one of the primary needs was structured, which, as recognized by sociologists, anthropologists, and historians, gave rise to the development of the State, whose objective was to provide protection to its associates; thus, security fell into the hands of the public authority. Indeed, the purpose of the political organization that since the Renaissance took the generic name of State, was to entrust the protection of the associates to an entity whose legitimacy was recognized by them, to which Thomas Hobbes called the Leviathan.

This transcendental step of civilization sought to categorically overcome the application of the Law of Talion -widespread in ancient societies and enshrined even in many legislations- or the so-called law of the jungle, according to which every individual must defend him or herself from others by any means. Hobbes was not misguided when he affirmed that man, in a natural state, is in a permanent state of war of all against all.

[...] in this condition there is no property or domain, no distinction between you and me; only what belongs to each one what he can take, and only insofar as he can keep it. All this can be affirmed of that miserable condition in which man finds himself by the work of mere nature. (Hobbes, 1982, p. 110)

Hobbes-considered a philosopher of absolutism- argued that the most suitable means to ensure peace in society is that every individual forsake protecting him or herself. Thus, all the advocates of contractualism -from the exponents of the natural law and scholasticism of the Middle Ages and the 15th and 16th centuries, to the modern times, like Locke and Rousseau- point to the social pact as the human need to attend to individual and collective security entrusting such matter to an institution, the State, which, by virtue of that pact, will be responsible for providing protection (Colombia, Corte Constitucional, 1997).

In the modern Rule of Law, the armed forces (including the police, tribunals, and courts) are political institutions belonging to the public power, which has as another of its main characteristics, that of being a civil power. This means that institutional armed bodies must be under the Rule of Law, and a subject to, as a whole and for all, the civil authority.

Therefore, the formation, structure, functions, and, in general, the basic organization of the public force must be duly enshrined in the Constitution and subject to the limitations and controls established by it and by the laws. This principle of the monopoly of material coercion at the head of the State implies that the Rule of Law cannot tolerate the existence of armed groups or sectors outside the armies and other regular institutions established at their service.

The principle of the military forces' exclusivity is not a purely rhetorical category; it has profound normative and practical consequences. Thus, according to this principle, it is certain that some functions and powers that are specific to the military forces -which at no time can be attributed to individuals- such as the exercise of intelligence work or the development of patrol activities intended to preserve public order. Individuals cannot possess or carry weapons of war, because "admitting that a particular or a group of individuals (PMSCs), own and carry weapons of war is equivalent to creating a new body of Military Forces" (Corte Constitucional de Colombia, 1995).

The exclusive regulation of the exercise of violence is an essential feature of every State, to such an extent that it is practically impossible to think of a state that does not attribute the monopoly of the regulation of the use of arms. Only the State can have a permanent institutional armed force. Weapons of war must be concentrated in specialized state bodies that have the task of protecting constitutional institutions and maintaining national sovereignty. This work is inherent to the state and cannot be delegated to PMSCs. The modern state is an institution that aspires to achieve the effective and legitimate monopoly of coercion in a given territory, seeking to avoid the dangers that, for social coexistence, involve the multiplication of private, armed powers.

What would happen in countries that, after long years of armed confrontation, try to find a peaceful solution to the conflict? Let's not forget that these processes are aimed at national reconciliation. Therefore, to empower a PMSC to carry out activities that are specific to the military forces disregards one of the purposes of the State, the promotion of peace and peaceful coexistence. The monopoly of violence cannot be imposed on the State's institutions, in many cases, introducing them to arrogate the power to act outside the framework of legality.

Mercenarism in the 21st century

In comparison with previous centuries, the world is in an era of relative peace, confrontations between symmetrical or conventional actors; namely, the states, has ceased considerably. Thus, the use of force for the solution of controversies is condemned by the international community. Now, disputes between States are resolved before international bodies, ranging from the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), which makes it clear that diplomacy is the tool par excellence used by foreign policy and international relations. In this sense, the States have considered other options for the exercise of power and have left hard power (military) as a last alternative. They have changed the latter by options such as soft power (diplomacy) and intelligent power (strategic intelligence) in the face of international condemnation of any hostile action.

However, as a result of the transformation of power relations, new threats have emerged that are far from the competence of any international jurisdiction, in large part because of their lack of recognition as subjects, given their very criminal or terrorist nature. Therefore, these asymmetric actors, typified in this way because of their non-state nature and because they use means of combat not proportional to the states, participate in non-international conflicts (Comité Internacional de la Cruz Roja, 2004).

Because of the nature of the conflict, some states are unable to provide military assistance in an internal conflict, in part, out of respect for the international principles established in the ius cogens principle. Thus, new actors that provide security services and military defense have also emerged, actors specialized in armed conflicts, private armies, such as the PMSCs.

Paradoxically, the previously mentioned companies are from developed states that guarantee non-developed states the services provided. There have also been cases in which these states hire specialized services to be provided in other countries. For example, in 2008, the United States renewed its contract with the Blackwater PMSC -branded for human rights violations- to protect senior US officials in Iraq (Atitar, 2008). In a recent case, in 2017, the same state sent mercenaries to Yemen. These services were initially contracted with the Blackwater PMSC but were later changed to DynCorp (La empresa de mercenarios DynCorp... 2016). Despite the strong allegations of sexual abuse attributed to this company during its operations, it was contracted in 2016 by the US Navy (Vos, 2017).

The above solicits the question, where do PMSCs come from and where do they operate? Currently, the companies most recognized for their security services are 1) Academi, formerly Blackwater, which changed its name because of allegations of human rights violations. It operated in Iraq and was hired by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA); 2) Defion Internacional, a company based in Peru, specialized in logistics services. It has operations in Dubai, the Philippines, and Iraq. Its main contracts were with Triple Canopy, Integral Security Company, and the Department of State of the United States; 3) Aegis Defense Services, founded in England. It provided services to 20 governments, as well as to the United Nations. Its involvement has been in 40 countries. It has offices in the United States, Afghanistan, and Bahrain. 4) Triple Canopy, which notably employs veterans of the US Special Forces. It maintains operations in Iraq. 5) DynCorp, a US company that employs mercenaries rather than US soldiers. It operated in Haiti, Bosnia, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Colombia. 6) Unity Resources Group, an Australian company that carried out operations in Iraq and is characterized by employing Latin soldiers (Ejércitos privados..., 2013).

Driven by the concern on the issue of the European military security companies present in states with internal armed conflict, the European Parliament urged the European Union to regulate their activities and external projection, given the legal vacuum in which they exist. Meanwhile, there is no commitment by the states or international organizations to regulate this type of activity. The above does not propose to prohibit PMSCs; it suggests that their responsibilities be enforced and that they should assume an ethical and moral stance against a business model that encompasses aspects concerning human integrity and dignity. It also highlights that the monopoly of the use of weapons should be solely the state's and that the PMSCs should not become an intervention alternative indirectly used by another state.

Impact of PMSCs on IHL

Noticeably, all the PMSCs maintain operations in the Middle East, a strategic zone of political and ideological instability that threatens, mainly, the interests of the United States and Europe. Thus, the persistent need to intervene through diplomatic and military channels in that region; this has made it an area of geopolitical dispute between international powers (Acosta, 2017).

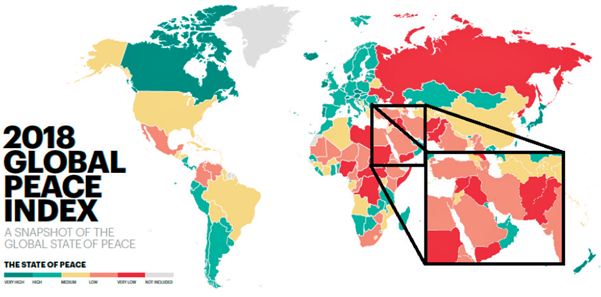

Según el Instituto para la Economía y la Paz (2018), una de las zonas de mayor inestabilidad es el Medio Oriente, seguida de África, en ambas operan la mayoría de EMSP extranjeras. Figure 1 shows A continuación, se presenta el Índice de Paz Global (figura 1), un indicador que ayuda a comprender cuáles son las regiones con más altos niveles de violencia en el mundo. Este indicador lo comprenden 23 variables, que incluyen guerras internas y externas libradas, gastos de defensa, homicidios, actos terroristas, sofisticación del armamento, cuerpos de seguridad que desarrollan actividades, etc. En este índice se denota el nivel de paz comparativa con otros países: el color verde representa el índice más bajo y el color rojo, el más alto.

According to the Institute for Economics and Peace (2018), the area of greatest instability is the Middle East, followed by Africa. The majority of foreign PMSCs operate in these areas. Figure 1 presents the Global Peace Index, an indicator that shows the regions with the highest levels of violence in the world. This indicator is comprised of 23 variables, which include internal and external wars waged, defense costs, homicides, terrorist acts, weapons sophistication, and security bodies that carry out activities, among others. This index shows a comparison of the levels of peace among countries. Green represents the lowest index and red represents the highest.

This indicator is constructed based on information from databases such as Uppsala Conflict Data Program, The Economist Intelligence Unit, Amnesty International, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, The Internal Displacement Monitoring Center, and The International Institute for Strategic Studies. All of these sources indicate a concentration of armed violence in Africa, the Middle East, and part of Central and South America, alongside with cases of violation of human rights.

In 2007, the private security firm Blackwater had close to 25,000 contractors, financed by the US, operating in Iraq. Added to the other companies operating in the area the number rose to nearly 50,000 contractors (Abrisketa, 2007) in a country that barely reached 29 million inhabitants, meaning that there was a foreign private security contractor for every 580 people, not counting the American and Iraqi army personnel.

In the same year, 17 Iraqi civilians were killed by machine gun fire by four contractors near Baghdad (Scahill, 2007). The perpetrators were initially sentenced to thirty years of house arrest. However, thanks to the intervention of the Circuit Court of Appeals of the District of Columbia, the charges were withdrawn in 2014. Evidently, there was a violation of IHL because it was found that the dead were indeed civilians.

In 2010, DynCorp was culled for hiring minors for sexual gatherings, some of them were even collectively abused by contractors in Afghanistan. Moreover, this company was accused of overreaching human rights to import, with the mafia, women to be prostituted (Vos, 2017).

A UN report (2013), stated that there were cases of overreaching of force by private security companies hired by landowners in the department of Colón (Honduras). These collaborations, supported by the state are linked to cases of "assassinations, disappearances, forced expulsions, and even sexual violence [...] private security personnel, hired by landowners, and armed with banned weapons -like the AK47- used to threaten and kill peasants" (ONU, 2013, p. 12).

According to Abrisketa (2007), the actions of private security agencies and their participation in armed conflicts must be classified as new mercenarism and, therefore, their activity must be considered illegal. However, the problem lies, in Abrisketa's words, in that "International Humanitarian Law does not address the legality of mercenary activities nor does it establish responsibility for being a mercenary" (Abrisketa, 2007, p. 5). Consequently, PMSCs' responsibility should be assumed by other bodies. However, because they are not recognized as international subjects, their acts are assumed by courts of nations where the main headquarters of these companies are located.

In this regard, it is considered that PMSCs must assume international responsibility for their actions, under the "combatant and prisoner of war status," as they take a direct part in hostilities, following Article 47 of the Protocol I of 1977.

On the other hand, the International Convention against the Recruitment, Use, Financing, and Training of Mercenaries, signed in 1989 -which came into force in 2001- ratifies Protocol I of article 47 on the concept of mercenary and upholds the five characteristics indicated above. However, the signatories are not developing States or major powers but only thirty States (Abrisketa, 2007).

In this sense, Abrisketa states that while the relevant international efforts are being made to regulate the activities of the PMSCs and their contractors (the mercenaries), the responsibility must be assumed by the state, following the provisions of the Geneva Conventions, namely:

a) The violations committed by its entities, including its armed forces; b) Violations committed by persons or entities trained by the state to exercise governmental authority; c) Violations committed by individuals or groups acting under the instructions of the state, or under its direction or control; and d) Violations perpetrated by private persons or groups that it recognizes and adopts as a conduct specific to the State. (Abrisketa, 2007, p. 11)

In short, the history of humanity, even the most recent, shows that whenever the state has been complacent about the existence of this type of organization (call it PMSCs or Private Security Service Providers), in the end, it has become a victim of that tolerance and impunity. Colombia, of course, is not foreign to this. One can simply evoke the lamentable and fateful facts of our dawn as a nation, when the Irish mercenary, Rupert Hand, of the British legions, who fought under the command of General Simón Bolívar in the war of independence of Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia, who after having been hired in the ports of England, viciously murdered our hero José María Córdova. Similarly, one can mention the services provided to Colombian drug traffickers by the Israeli mercenary Yair Klein, who was captured in Moscow and later requested in extradition to respond to the Superior Court of Manizales, which sentenced him to ten years and eight months in prison for his participation in the strengthening and training of self-defense groups in war practices.

The modern state legal systems1 do not address the activities of the PMSCs and, if they do, it is done deficiently. This inadequacy produces the transfer of security duties of public authorities to these companies, apparently, in an attempt to avoid the responsibilities of the state concerning human rights and IHL.

Conclusions

It can be asserted that we face an ethical and moral crisis in the 21st century because of the commercialization of security and defense services offered by the PMSCs. Hiring salaried professional soldiers, specialists in intervening in armed conflicts, goes against the international agreements that favor of global peace.

This paradox arises because public international law and the international bodies responsible for preserving global stability and empowered to condemn any act against human dignity have not achieved significant progress to regulate and control the activities of the mentioned companies. On the contrary, there are still unresolved legal gaps that make their activities possible and affect the legitimacy of the institutions that protect HR. Actors such as PMSCs are not condemned in a timely manner and in accordance with the mandates of these institutions for violations of rights in conflict zones.

According to the United Nations Organization, more than 20,000 mercenaries are involved in armed conflicts in the Middle East and Asia, data that is in accordance with those registered by the Institute for Economics and Peace, whose studies affirm that countries such as Iraq, Libya, Syria, and Somalia have a significant presence of PMSCs. Therefore, these companies operate beyond the rules of international law; this generates a gray legal zone of marginality that allows them to evade responsibility and attain impunity to avoid direct convictions for their actions against HR.

In this sense, we face two problems. The first problem is the economic and business nature of these organizations, which prevents them from being subjects of international law and, therefore, assume any responsibility. The second issue is that a mercenary's con-duct and actions are not considered criminal and illegal acts. As a result, security companies and their contractors can continue to operate without any social responsibility.

In brief, it is sustained that the PIL does not establish legal limits for PMSCs. Uncertainties remain about the principle of state's monopoly on the use of force in the face of armed conflict scenarios because in the event of a regulatory vacuum, it allows the financing of war by indirect means.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Escuela Militar de Cadetes "General José María Córdova" and the Escuela Superior de Guerra "General Rafael Reyes Prieto" for their support in the production of this article.

REFERENCES

Ábrego, M. (2013). Palimpsestos: escrituras y reescrituras de las culturas antigua y medieval. Buenos Aires: Editorial de la Universidad Nacional del Sur. [ Links ]

Abrisketa, J. (2007). Blackwater: los mercenarios y el derecho internacional. Fundación para las Relaciones Internacionales y el Diálogo Exterior, 8. [ Links ]

Acosta, H. (2017). Siria, un pequeño ajedrez geopolítico. Observatorio de Seguridad y Defensa, 2(5), 9-10. Recuperado de https://issuu.com/observatoriosd/docs/bolet__n_5_-_2017_v4. [ Links ]

Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas. (1974). Definición de la agresión [Resolución 3314 (XXIX) de la Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas]. Recuperado de http://www.un.org/es/documents/ag/res/29/ares29. [ Links ]

Atitar, M. (2008). Estados Unidos renueva el contrato de la empresa de mercenarios Blackwater en Iraq. Recuperado de http://www.mundoarabe.org/estados_unidos_blackwater.htm. [ Links ]

Banco Mundial. (2016). PIB (US$ a precios actuales). https://datos.bancomundial.org/indicador/NY.GDPMKTP.CD?locations=CO-US. [ Links ]

Barría, C. (2017, septiembre 25). Cuáles son las 5 mayores empresas militares del mundo y qué armamento producen. BBC News. Recuperado de https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-41314528. [ Links ]

Braidot, N. (2011). El feudalismo. Orígenes y desarrollo, pervivencia de las estructuras señoriales en el Medievo. Interpretaciones históricas. Clio, 37. [ Links ]

Colombia, Corte Constitucional de Colombia. (1995). Sentencia C-038 de 1995. Bogotá. [ Links ]

Colombia, Corte Constitucional de Colombia. (1997). Sentencia C-572 de 1997. Bogotá. [ Links ]

Comité Internacional de la Cruz Roja. (2004). Los Convenios de Ginebra de 1949 y sus Protocolos adicionales. Recuperado de https://www.icrc.org/spa/war-and-law/treaties-customary-law/geneva-conventions/overview-geneva-conventions.htm. [ Links ]

Comité Internacional de la Cruz Roja. (2006). El derecho internacional humanitario y las empresas militares y de seguridad privadas. Recuperado de http://www.icrc.org/spa/resources/documents/faq/pmsc-faq-150908.htm. [ Links ]

ONU. (2013). Informe del Grupo de Trabajo sobre la utilización de mercenarios como medio de violar los derechos humanos y obstaculizar el ejercicio del derecho de los pueblos a la libre determinación. Recuperado de https://www.ohchr.org/SP/Issues/Mercenaries/WGMercenaries/Pages/WGMercenariesIndex.aspx. [ Links ]

Convenios de Ginebra. (1907). Convención de La Haya de 1907para la resolución pacífica de controversias internacionales. Recuperado de http://www.papelesdesociedad.info/IMG/pdf/convenios_de_la_haya_1889_y_1907.pdf. [ Links ]

Douglas, W. (2001). Emigrantes vascos: contrates en los modelos de adaptación en Argentina y en oeste norteamericano. Revista Estudios Paraguayos, 1(191). [ Links ]

Ejércitos privados: los grupos de mercenarios más importantes del mundo. (2013, junio 29). RT noticias. Recuperado de https://actualidad.rt.com/actualidad/view/98695-eeuu-mercenario-ejercito-privado-irak-blackwater. [ Links ]

Forster, J. (2004). Los actores armados no estatales y las normas humanitarias internacionales. Recuperado de https://www.icrc.org/spa/resources/documents/misc/66vlcc.htm. [ Links ]

La empresa de mercenarios DynCorp sustituye a Blackwater en Yemen. (2016, marzo). Al-Manar. Recuperado de http://archive.almanar.com.lb/spanish/article.php?id=123143. [ Links ]

Expertos de la ONU analizan aumento de mercenarios y su impacto en los derechos humanos. (2015 julio 23). Organización de Naciones Unidas. Recuperado de https://news.un.org/es/story/2015/07/1335361. [ Links ]

Fallah, K. (2006). Actores privados: el estatuto jurídico de los mercenarios en los conflictos armados. Recuperado http://www.icrc.org/spa/resources/documents/article/review/74ummf.htm. [ Links ]

Güell, S. (2010). El papel de las ONG, ETN y EMSP en la resolución de crisis relacionadas con la seguridad internacional. Una perspectiva desde el derecho internacional. Cuadernos de Estrategia, 147, 25-73. [ Links ]

Güell, S. (2011). Las empresas militares y de seguridad privada. Rasgos característicos. Revista por la Paz, 9. [ Links ]

Hobbes, T. (1982). ElLeviatán. Bogotá: Editorial SKLA. [ Links ]

Instituto para la Economía y la Paz. (2018). Global Peace Index. Recuperado de http://visionofhumanity.org/app/uploads/2018/06/Global-Peace-Index-2018-2.pdf. [ Links ]

Jiménez, J., Acosta, H., & Múnera, A. (2017). Las disidencias de las FARC. En J. Cubides, & J. Jiménez (Eds.), Desafíos para la seguridad y defensa nacional de Colombia. Teoría y praxis. Bogotá: Escuela Superior de Guerra. [ Links ]

Nikken, P. (1994). El concepto de derechos humanos. En R. Cerdas, & R. Nieto (Eds.), Estudios básicos de derechos humanos I (pp. 15-27). San José: Prometeo. [ Links ]

Preux, J. (1989). Estatuto de combatiente y de prisionero de guerra. Recuperado de https://www.icrc.org/spa/resources/documents/misc/5tdm4r.htm. [ Links ]

Scahill, J. (2007). Blackwater. The rise of the world's most powerful mercenary army. EE. UU.: Nation Books. [ Links ]

Vos, E. (2017, abril 20). DynCorp, la empresa militar privada en el epicentro de un escándalo de política exterior estadounidense. Omoya. Recuperado de https://umoya.org/2017/04/20/dyncorp-la-empresa-militar-privada-en-el-epicentro-de-un-escandalo-de-politica-exterior/. [ Links ]

1South Africa is the only country whose legislation expressly prohibits nationals from selling their military training to a foreign country immersed in armed conflict. It is also one of the few countries that regulates foreign military assistance and considers the activity of mercenaries illegal.

To cite this article: Jiménez Reina, J., Gil Osorio, J. F., & Acosta Guzmán, H. (2019). The incidence of private military and security companies on international humanitarian law. Revista Científica General José María Córdova, 17(25), 113-129. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21830/19006586.370

The articles published by Revista Cientifica General Jose Maria Cordova are Open Access under a Creative Commons license: Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode

Disclaimer The authors declare that there is no potential conflict of interest related to the article. This article was produced thanks to the cooperation between two research projects: Observatory of Operational Law by the Military Sciences research group of the Ecsuela Militar de Cadetes "General José María Córdova" and "The Military Leadership Before the Post-Agreement Scenario: Impact of the Damascus Doctrine on the Role of the Military Leader and the Social Challenges Generated after the Signing of the Agreement for the Termination of the Conflict and the Construction of Stable and Lasting Peace" by the Masa Crítica research group of the Escuela Superior de Guerra "General Rafael Reyes Prieto."

Funding This article was completed with the funding of the Escuela Militar de Cadetes "General José María Córdova" and the Escuela Superior de Guerra "General Rafael Reyes Prieto."

About the authors

Jonnathan Jiménez Reina is a Ph.D. candidate in International Security from the Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED), Spain. He holds a Master's degree in National Security and Defense from the Escuela Superior de Guerra "General Rafael Reyes Prieto," Colombia. He is a professional in Politics and International Relations at the Universidad Sergio Arboleda, Colombia. He is editor of the scientific journal, Estudios en Seguridad y Defensa, of the Escuela Superior de Guerra "General Rafael Reyes Prieto" and a professor of the Master's program in Strategy and Geopolitics of this same institution. He is also a professor in the Faculty of Law and the Faculty of International Relations of the Escuela Militar de Cadetes "General José María Córdova." https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9042-834X, contact: jonnathan.jimenez@esdegue.edu.co

Juan Fernando Gil Osorio is a Ph.D. candidate in Law from the Universidad Externado de Colombia. He has a Master's degree in Human Rights and Democratization from the Universidad Externado de Colombia in arrangement with the Universidad Carlos III of Madrid, España. He is a lawyer of Faculty of Law of the Universidad de Medellín, Colombia. He is a Captain of the National Army of Colombia. He is the director of the Observatory of Occupational Law and the academic coordinator of the Faculty of Law of the Escuela Militar de Cadetes "General José María Córdova." https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6605-6846, contacto: juan.gil@esmic.edu.co

Henry Mauricio Acosta Guzmán is a student in the Master's program in National Security and Defense of the Escuela Superior de Guerra "General Rafael Reyes Prieto," Colombia. He is a political scientist at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia. He is a researcher in training in the Department of Ethics and Leadership of the Escuela Superior de Guerra "General Rafael Reyes Prieto," Colombia. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4485-8845, contacto: henry.acosta@esdegue.edu.co

Received: September 20, 2018; Accepted: November 01, 2018; Accepted: January 01, 2019

text in

text in