Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Revista Científica General José María Córdova

versão impressa ISSN 1900-6586versão On-line ISSN 2500-7645

Rev. Cient. Gen. José María Córdova vol.17 no.27 Bogotá jul./set. 2019

https://doi.org/10.21830/19006586.436

Ciencia y Tecnología

Sexual violence in post-conflict zones: Reflections on the case of the Central African Republic

* Universidad Politécnica Estatal del Carchi (UPEC), Tulcán, Ecuador. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0899-1788 jaime.jimenez@upec.edu.ec

** Universidad Politécnica Estatal del Carchi (UPEC), Tulcán, Ecuador. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9973-0502 daniel.jimenez@upec.edu.ec

This article exposes allegations of sexual violence from 2015 to 2016 by United Nations peace-keepers during the peace operation of the Central African Republic. The main objective is to highlight accusations of sexual exploitation and abuse and condemn the measures implemented by the United Nations. An attempt is made to answer whether international humanitarian law should judge acts of sexual violence perpetrated by peacekeepers towards civilians in post-conflict zones. The analysis, carried out through bibliographic-documentary research, intends to oppose impunity and reinforce the credibility of peace operations, as well as their personnel as instruments of conflict resolution in the international scenario.

KEVWORDS: Anders Kompass; Central African Republic; human rights; international human right; peacemakers; sexual abuse

El presente artículo expone las denuncias de violencia sexual durante la operación de paz de la República Centroafricana en cuanto a casos perpetrados de 2015 a 2016 por parte de los pacificadores de las Naciones Unidas. El objetivo central es evidenciar las acusaciones de explotación y abuso sexuales y criticar las medidas implementadas por las Naciones Unidas. Además, se intenta responder a la pregunta: ¿los actos de violencia sexual hacia los civiles por parte de los pacificadores en las zonas posconflicto deben ser juzgados por el derecho internacional humanitario? El análisis -llevado a cabo mediante una investigación bibliográfica-documental- pretende aportar a la lucha contra la impunidad y repotenciar la credibilidad en las operaciones de paz y su personal como instrumentos de resolución de conflictos en el escenario internacional.

PALABRAS CLAVE: abuso sexual; Anders Kompass; derechos humanos; derecho internacional humanitario; pacificadores; República Centroafricana

Introduction

In the '90s, a new conflict model appears in the international scene: The armed conflict, evidencing the incompatibility in a government, a territory or both, where the use of armed between the counterparts forces is central (Themnér & Wallensteen, 2014). The new wars emerge within this context, clearly diverging from those in the Clausewitzian thinking and regarded as civil or internal wars because of their local and transnational influences (Kaldor, 1999/2001).

The new wars use direct violence to "maintain a constant feeling of fear and insecurity, and perpetuate reciprocal hatred" through three technics (Kaldor, 1999/2001, pp. 129-130): 1) systematic assassinations by government and armed forces; 2) ethnic cleansing and forced displacement; and 3) the impossibility to inhabit lands through the use of weapons (landmines, rockets, and bombs), and food deprivation, as well as psychological pressure.

These technics have become the State's means to seize power and the lawful monopoly of violence. Sexual violence has also been turned into an instrument with a dual purpose: 1) ethnic cleansing that seeks to obliterate all the opposition's offspring through genital mutilation, and 2) as a means of reward/deterrence. (Bruneteau, 2008).

However, the spectrum of sexual violence has changed. Now, the issue lies in that the insurgent groups are not the ones who exercise sexual violence, but also the peacekeepers whose mission is to protect civilians in processes of transition towards the construction of peace.

This article exposes the actions of Anders Kompass and NGOs fronting the sexual violence carried out by United Nations peacekeepers in the Central African Republic (CAR) between 2015 and 2016. Its main objective is to expose the impact of Anders Kompass' research on this topic. It is divided into three sections: 1) sexual violence as a weapon of war and peace; 2) the Kompass report on sexual abuse and exploitation (Kompass, 2015); and 3) measures taken by the UN to combat sexual violence.

The first section identifies the relationship between the armed conflict and the civil population to argue that in times of war, sexual violence has been adopted as an instrument against women, men, and children. However, this concept must be extended to post-conflict zones where sexual violence is used as an instrument of satisfaction instead of security.

The second section highlights the fact that accusations of sexual violence have been documented since the 1990s. In response to this, the Zeid report (Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas [UNGA], 2005), exposes complaints against UN civil, police, and military personnel for sexual violence against civilians (women and children). For this reason, Anders Kompass was assigned to the CAR to collect, assess, and report on the sexual violence perpetrated by the Sangaris Force (France) against civilians in exchange for food and economic resources, although accusations on this matter continue to be filed by some NGOs, such as Human Rights Watch (HRW), Amnesty International (AMIN), and Aids-Free World.

The third section discusses the instruments to stop sexual violence and shows sanctions allocated to the peacekeepers for their abuses. The first part of this third section briefly discusses the "special measures of protection against exploitation and sexual abuse," promoted by the UN General Secretary, Ban Ki-moon. The second part critically describes the sanction mechanisms and the responses to these acts by the UN and the peacekeepers' member states.

Lastly, it is important to emphasize that acts of sexual abuse and exploitation perpetrated by UN peacekeepers must be judged by international humanitarian law (IHL) as a priority before the national legislation of the UN member states and considered war crimes. The mechanisms adopted by the UN to address this problem are ad hoc and preventive rather than punitive. However, it is essential to take into consideration the repercussions of these acts on men, women, and children when applying international humanitarian regulations.

Even if a "zero-tolerance policy" is upheld to face sexual abuse and exploitation, peace operations should establish mechanisms not only for reporting and investigation but also for sanction and reparation (not only economic but also social). Similarly, peace operations must be conducted focusing on human rights and gender, both for peacekeepers and civil population. Therefore, it is imperative for peace operations to intensify the training of civilian, military, and police personnel to protect civilians and maximize the presence of women in post-conflict zones.

Methodology

This study is a qualitative approach that focuses on analyzing the implications of sexual abuse and exploitation by UN peacekeepers, based on the research carried out by Anders Kompass. For its development, a compilation of documentary and bibliographical information was made from three diflerent types of sources: 1) documents of official organizations and institutions, 2) books, articles, and research reports and 3) written and digital press articles.

Resolutions gathered from the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), the United Nations Secretary-General (UNSG), the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), and the of Peace Operations Training Institute were included in the first group, in addition to the documents from Human Rights Watch (HRW), Amnesty International (AMIN), and Aids-Free World. The second group consisted of books and articles on the relationship between sexual violence and the construction of peace, the role of peace operations in post-conflict zones, and the relationship between peacekeepers and the civil population. Lastly, the third group of sources was made up of analyzed press releases from The Guardian and The Telegraph.

Sexual violence as a weapon in times of war and peace

In armed conflicts, civilian casualties and destruction of civil infrastructure are the deliberate results of attacks against non-combatants. In this regard, it should be noted that there is no dividing line between civilians and combatants; this generates incursions of violence against the former by an armed faction (Secretaría General de las Naciones Unidas [UNSG], 1999). Therefore, in armed conflicts "the consequences [are] diflerent for men and women, while it is true that most combatants are men, women (...) and boys [and girls] represent the largest proportion of civilians aflected by conflicts" (UNSG, 1999, p. 5). As a result, men, women, and children are more vulnerable to sexual violence and exploitation (Jiménez, 2012).

Sexual violence has become a "war weapon," a right of the victor over its enemies (Jiménez, 2012). In this sense, sexual violence in times of war has become naturalized and has sidestepped gender. For instance, sexual violence on men consisted of forced penetra-tion and masturbation, undressing and being subjected to genital violence to sterilize and subvert the virility of their enemies (Jiménez, 2012; Zawati, 2007). On the other hand, young boys and girls, as soldiers, receive a treatment similar to that of adults and are sentenced to the service of shippers to transport ammunition or wounded soldiers.

Within this context, apart from military tasks such as surveillance and espionage, boys and girls are forced to have sexual relations with their commanders and, in the heat of the armed struggle, the latter violate and mutilate the genitals of women (Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas [UNGA],1996). Finally, there is the sexual violence of combatants against women: sexual slavery, prostitution, unwanted pregnancy, and forced sterilization (UNGA, 2000).

However, if armed conflicts are a trigger for violence against the civilian population, especially against women and girls (without diminishing the importance of men and boys), the post-conflict zones also represent a scenario of inequality and imbalance between genders and between UN staff and civilians, given that there have been several violations of the code of conduct of peacemakers in peacekeeping (Jiménez, 2012).

The violation of the code of conduct has referred to acts of exploitation and sexual abuse in an "uncertain and insecure territory, dominated by the fragility and the total absence of the rule of law" (Jiménez, 2012, p. 183). The State's absence drives a "condition of war" of all against all, where fear and violent threat prevail (Hobbes, 1651/2012, pp. 104-105). This condition highlights survival as a need that must be satisfied, as well as individual and collective security, in the face of likely injustice, inequity, disagreement, and dissatisfaction (Webel, 2007). In other words, in the absence of the State, the civilian population's vulnerability is increased, leaving security, subsistence, and satisfaction of needs in the hands of UN peacekeepers; this blurs power relations (Jiménez, 2012).

Therefore, the thesis that there is a higher propensity for sexual violence in conflict zones must be eradicated. This study explicitly reveals abuse and sexual exploitation by UN peacekeepers in post-conflict zones. The male/aggressor and female/victim paradigm must also be discarded (Jiménez, 2012) and reformulated with a new equation, in war-time and peacetime, sexual aggression against women, men, girls, and boys are the same, to avoid minimizing the importance of the spectrum that forms civilians' concept.

Indeed, without the adoption of measures to address the crimes of sexual violence committed by peacekeepers sent to protect civilians, "the credibility of the United Nations and the future of peacekeeping operations are at risk" (UNGA, 2016b, p. 3). To expose these acts of sexual violence, the following section addresses sexual abuse and exploitation by UN peacekeepers in post-conflict zones, especially in the CAR.

The Kompass Report and the support of the NGOs

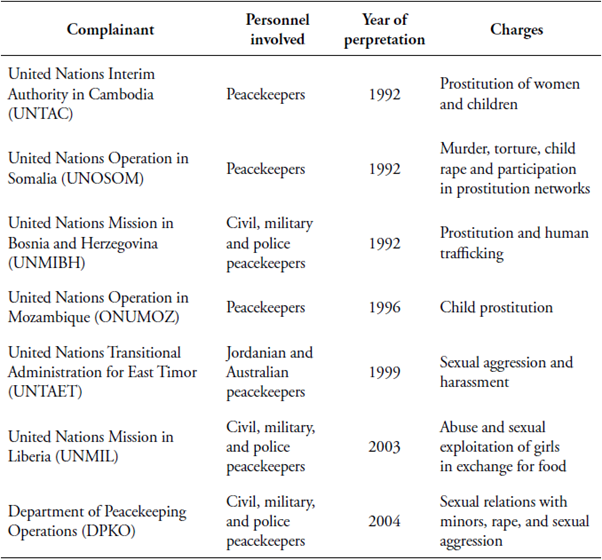

Sexual abuse and exploitation exercised by peacemakers are neither recent nor a new concept (Kent, 2005, p.87). In 1992, the first reported cases involved the United Nations Interim Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) concerning a prostitution network of women and children (Jiménez, 2012; Koyama & Myrttinen, 2007). In the same year, acts of murder, torture, child rape, and participation in prostitution networks were reported in the United Nations Operation in Somalia (UNOSOM) (Kent, 2005). This phenomenon is shown explicitly in Table 1.

Table 1 Complaints against UN peacekeepers for sexual violence (1992-2004)

Source: Created by the author, based on Jiménez (2012), Koyama & Myrttinen (2007), Kent (2005), UNGA (1996, 2005), and Martin (2004).

The Machel Report5 (UNGA, 1996) details that the peacekeepers of the United Nations Operation in Mozambique (ONUMOZ) "used young people between 12 and 18 years old to practice prostitution (…) [consequently] the arrival of peacekeeping forces has been related with a rapid increase in child prostitution" (UNGA, 1996, p. 33).

Similarly, in 1992, at the United Nations Mission in Bosnia and Herzegovina (UNMIBH), accusations were filed against military, civilian, and police personnel involved in prostitution and human trafficking (Jennings & Nikolic-Ristanovic, 2009; Jiménez, 2012). In 1999, The United Nations Transitional Administration for East Timor (UNTAET), had the incidence of sex workers from Bangkok and Pattaya (Koyama & Myrttinen, 2007, pp. 33-34). Timorese also women accused the Jordanian and Australian peacekeeping contingent of sexual assault, as well as sexual harassment (Koyama & Myrttinen, 2007).

However, peacekeepers in Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) have reported the most cases of sexual abuse and exploitation (UNGA, 2005). There have also been serious accusations against the United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL in 2003) where military, civilian, and police personnel of the mission had engaged in sexual abuse and exploitation of 12-year-old girls in exchange for food (Martin, 2004).

A detailed study of these acts was the Zeid Report6, which offered a policy against sexual abuse and exploitation and a report on sexual violence complaints. The policy establishes a comprehensive strategy in four areas: a) rules of conduct, b) method of investigating complaints of abuse, c) rendering of accounts, and d) financial and legal considerations. This strategy provides capacities for prevention and responses and assistance to victims (Kent, 2005).

The report evidences that, in 2004, the Department of Maintenance Operations for Peace (DPKO), received 16 complaints against civilians, nine against police, and 80 against military personnel, for a total of 105 complaints (UNGA, 2005, p. 9). Among these complaints, 45% were related to sexual relations with minors, 13% to rape, 5% to sexual assault, and 6% to other forms of sexual exploitation and abuse (UNGA, 2005).

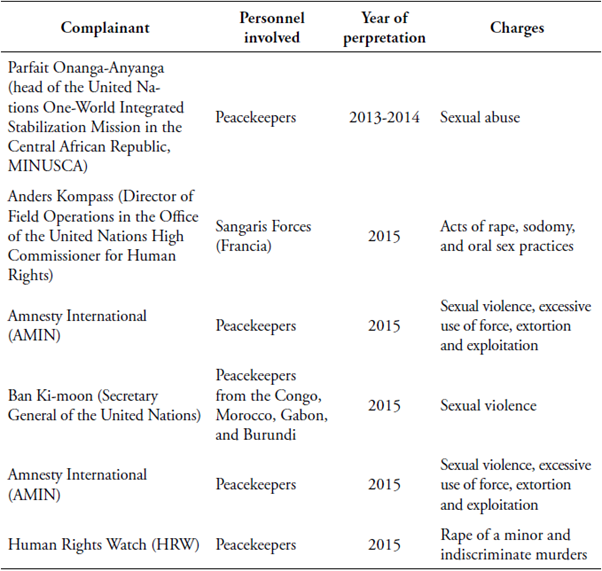

With this in mind, the most obvious question is, What is the relevance of Anders Kompass,7 if there have already been policies and documentation on sexual abuse and exploitation? The response has three dimensions: a) the tenacity of the complaints, b) the support of the NGOs, and c) the responses of the UN. Starting from the first dimension, Anders Kompass was assigned by SGUN Ban Ki-moon to investigate the accusations of sexual violence against the peacemakers. While carrying out the investigation, Kompass compiled information that showed the involvement of the Sangaris Force (France) in the sexual abuse of children in the displaced persons' camp at the airport of the capital of the CAR (Bangui), acts that were perpetrated between December and June of 2014 in exchange for money or food, but which were reported in 2015 (Laville, 2016a, 2016c). These complaints are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2 Complaints against UN peacekeepers for sexual violence (2015)

Source: Created by authors, based on Laville (2016a, 2016b, 2016c), Chonghaile (2016), De la Torre (2016), HRW (2016), AMIN (2016), AIDS-FW (2015), Ross (2016), UNGA (2016a, 2016b), Deschamps, Jallow and Sooka (2015), “UN finds more” (2016), and UNSC (2016).

With evidence, Anders Kompass formulated a report entitled Sexual Abuse by the International Armed Forces (Laville, 2016a), which detailed the acts of rape, sodomy, and oral sex practices exercised by peacekeepers against Central African children (Laville, 2016c). The report was delivered to Roberto Ricci, the head of Rapid Response and the Peace Missions Section of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in July 2014. Similarly, he contacted Flavia Pansieri, deputy director of OHCHR. However, there were no responses to the report of rapes in the CAR, nor from the French and UN authorities (Kompass, 2015).

Without an official response, Kompass leaked the information to the media and uncovered the problem of sexual exploitation and abuse in the CAR, as well as the “lack of accountability and the UN's institutional breakdown" (Deschamps et al., 2015; Laville, 2016a). Kompass was listed as a "whistleblower" on UN-related cases of sexual abuse of children and women in the CAR (Laville, 2016c). For nine months, he was subjected to a disciplinary investigation which was headed by the Office of Internal Oversight Services (OIOS) from which he was exonerated from the charges. Table 3 shows the potential of the complaints presented by Anders Kompass.

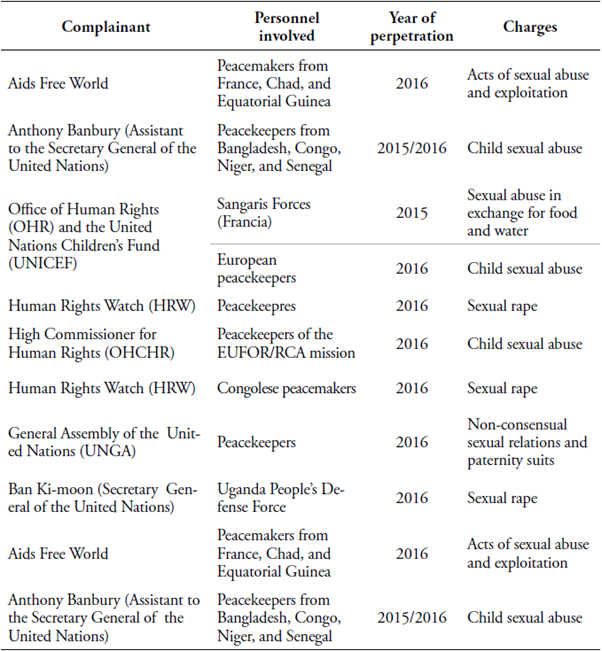

Table 3 Complaints against UN peacekeepers for sexual violence (2016)

Source: Created by the authors, based on Laville (2016a, 2016b, 2016c), Chonghaile (2016), De la Torre (2016), HRW (2016), AMIN (2016), AIDS-FW (2015), Ross (2016), UNGA (2016a, 2016b), Deschamps et al. (2015), “UN finds more” (2016), and UNSC (2016).

Anders Kompass' actions motivated the NGOs to join the dissemination and accusation of exploitation and sexual abuse in the CAR. Thus, for example, the head of the United Nations Integrated One-World Organization for Stabilization in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA), Parfait Onanga-Anyanga, underlined the existence of 100 sexual abuse allegations from 2013 to the beginning of 2014 (Chonghaile, 2016). Human Rights Watch (HRW) denounced, on August 11, 2015, the investigation of UN troops for alleged involvement in the rape of a minor and indiscriminate killing (De la Torre, 2016), and in January 2016, documented eight cases of rape ( ). He added that in February 2016, there was the case of a 14 and an 18-year-old girl, victims of Congolese peacekeepers between October and December 2015 (Laville, 2016b).

Investigations by AMIN show that peacekeepers have been accused of involvement in sexual violence, excessive use of force, extortion, and exploitation (AMIN, 2016). For example, in 2015, AMIN presented evidence of the rape of a 12-year-old girl (AMIN, 2015). Similarly, Aids Free World, in its "Blue Code" campaign pressures to stop the impunity of the peacemakers for acts of sexual abuse and exploitation (AIDS-FW, 2015; Ross, 2016). This NGO provided a copy of the Kompass Report, accusing peacekeepers in France, Chad, and Equatorial Guinea of sexual abuse of children in the CAR (AIDS-FW, 2015; De la Torre, 2016).

As a result of the filtering of the Kompass Report and the actions of the NGOs, internal pressure was generated in the UN to provide effective and immediate actions. The UN responses were specified in the UNGA's Resolution 70/286 to complete a report for an independent review of the sexual exploitation and abuse committed by international peacekeeping forces in the CAR (UNGA, 2016b).

The so-called "CAR Panel" made it clear that the UN staff was more concerned with how the information had been leaked to the French authorities than with effectively managing the evidence, seeking the well-being of the victims, and demanding accountability from human rights violators (UNGA, 2016b). The report focused on policies against sexual exploitation and abuse and the protection of human rights by UN and UNSC to endorse the policy initiative of "Human Rights up Front"8 (De la Torre, 2016).

At the same time, the Office of Human Rights (OHR), together with the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), revealed accusations made in 2015 of six Central African children, victims of sexual abuse in exchange for food and water by members of the Sangaris Forces (Deschamps et al., 2015). The investigations, in January 2016, resulted in six cases of sexual abuse of children by European peacekeepers (De la Torre, 2016) and a UN team interviewed five girls and a boy who were victims of sexual abuse in 2014 in the CAR ("UN finds more," 2016).

On January 29, 2016, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OACHD), after investigations, evidenced cases of sexual abuse perpetrated by the EUFOR/RCA Mission (De la Torre, 2016; UNSC, 2016a ). Similarly, in 2016, the UNSG Assistant to the Secretary-General, Anthony Banbury, exposed four new cases of child sexual abuse by peacekeepers in Bangladesh, Congo, Niger, and Senegal after 22 cases had been filed in 2015 (Laville, 2016b; "UN finds more," 2016). Thus, in February 2016, the UNSG appointed Jane Holl Lute as special coordinator to improve the United Nations' response to exploitation and sexual abuse (De la Torre, 2016; HRW, 2016).

In the framework of investigations, in February 2016, the UNGA stated that there were 22 reports from the CAR in 2015; 15 were the result of sexual activities with minors, five for non-consensual sexual relations with 18-year-olds, and two paternity suits (UNGA, 2016b). The UNSG's report of February 12, 2016, identified acts of rape by the Uganda People's Defense Forces (UPDF) towards a 17-year-old girl and a minor in 2013 (UNSC, 2016). The report also stated that there were ten complaints of rape of children in 2015 by four peacemakers in the DRC, one from Morocco, one from Gabon, and two from Burundi (UNSC, 2016). In total, there were cases of 513 girls and eight boys, all victims of rape (UNSC, 2016).

If the accusations of the NGOs, the press, and the investigations of the different UN organs are not enough, the question is: What concrete legal and criminal actions will be initiated against the abuses and the sexual exploitation? A response from the UN Secretary General's Report, Ban Ki-moon, was "Special measures of protection against exploitation and sexual abuse." These instruments should protect the victims of such acts and punish the perpetrators. However, these measures are not a solution to the problem. The following section presents and analyzes some of the problems and challenges of this instrument against sexual violence.

Actions, problems, and challenges of the UN against sexual abuse and exploitation

The Zeid Report is a set of initiatives to stop sexual abuse and exploitation; however, it is ad hoc, and not adequate to deal with the problem (UNGA, 2005). The Ki-Moon Report not only collects the previous instruments against sexual abuse and exploitation but also specifies a robust body of initiatives that focus on a policy of "zero tolerance for sexual violence" (UNGA, 2016a). This policy aims to "ensure that complaints are investigated thoroughly and without delay" so that both the UN and the Member States guarantee accountability and that the appropriate criminal measures are imposed (UNGA, 2016a). In other words, sexual abuse and exploitation should not be considered a simple disciplinary infraction but rather a disregard of human rights and international humanitarian and criminal law.

An essential point of the report is the establishment of two factors that influence sexual abuse and exploitation. The first is sexual violence associated with the conflict. Areas of post-conflict zones are marked by a mixture of extreme poverty, vulnerability, and lack of access to basic needs; this forces women and girls to engage in prostitution, while the peacemakers take advantage of the situation of uncertainty (UNGA, 2016a). However, two issues must be considered: a) compulsory prostitution produced by family pressure or burden, and b) prostitution without coercion, as a means of income or food in post-conflict zones where there are no sources of work. This relates the armed personnel with economic resources and the naturalization of prostitution as a work option.

The second factor is the change of the contingents in peace operations. This circumstance captures the lack of training regarding the rules of conduct, the excessive duration of military and police contingents, living conditions, and infrastructure for well-being and family communication (UNGA, 2016a). This factor highlights the institutional weakness, the insufficiency of the training of military and police pre-deployment contingents, the lack of clarity in the memoranda of understanding for peace operations and, mainly, the lack of training in gender and security, and the shortage of female uniformed and civilian personnel.

Although "transparency and accountability" are instruments of the Zero Tolerance Policy, the apparatus proposed by the Ki-moon Report only focuses on reporting, investigating, and sanctioning administratively. Therefore, its central reproach is that, although peacemakers have criminal accountability, the national jurisdiction applicable to the crime is insufficient. The Zeid Report also specifies that peacekeepers are subject to the criminal authority of the primary country (UNGA, 2005). Similarly, the Ki-moon Report contends that the UN will inform member states of accusations of sexual violence by peacekeepers (UNGA, 2016a).

So, are the criminal judgments of member states to punish the peacemakers accused of sexual exploitation and abuse consistent and fair in the face of the acts perpetrated or are the penal sanctions to peacemakers merely symbolic acts to comply with the policy of zero tolerance and UN transparency? The answer is that criminal sanctions are not equivalent to the act perpetrated against the civilian population because they are representative and symbolic rather than punitive.

Three examples illustrate and support this response. A complaint in 2015, indicated that a police officer had been suspended for nine days for maintaining sexual exploitation relationships with a woman. The complaints of 2014 allowed a military man to be condemned to six months of imprisonment for sexual activities with a minor. Within the complaints between 2010 and 2013, two cases were filed, the first was dismissed for the time elapsed and the second was closed because the probation officer retired before the conclusion of the disciplinary procedure (UNGA, 2016a).

These examples depict the inadequacy of criminal justice in the Member States. Given this, international norms must be reviewed to reinterpret the sanctions on exploitation and sexual abuse. To this end, three elements must be considered: 1) the issue of immunity, 2) sexual violence not as a disciplinary offense, but as a war crime and 3) the primacy of international law over national law and the need for mixed courts.

The first element addresses the immunity enjoyed by UN personnel in peace operations concerning to the exercise of national criminal jurisdiction over the acts committed when performing its functions, leaving them under the exclusive jurisdiction of the sending member state (UNGA, 2006). However, the fundamental condition to enjoy this immunity is "to respect all local laws and regulations as a condition to be able to enjoy prerogatives and immunities in that State" (UNGA, 2006). This condition allows, on the one hand, to consolidate the UN's commitment to the rule of law and, on the other, to generate credibility in peace operations missions. However, if the perpetrators abuse and sexually exploit, they are violating local regulations, threatening peace and security, and jeopardizing the credibility of the peace operation and the UN mission. So, should this immunity be suppressed?

The UN Charter (UNC), in Article 105, states that representatives of the organization's member states and officials shall enjoy the privileges and immunities necessary to perform their functions (Naciones Unidas [UN], 1945). However, the same article 105 underscores that the UNGA can make provision to repeal the peacemakers' diplomatic immunity in cases of investigation and accusation of non-compliance with UN standards of conduct, IHL, and human rights, to make the processes of accountability effective (UNGA, 2016a). In practice, after an armed conflict, the judicial system of the receiving states is under reconstruction, which means that the peacekeepers renounce their immunity and are subject to the jurisdiction of their respective states, but this is a condition for the receiving state, and the victims remain in impunity (UNGA, 2006).

The second element reassigns sexual violence as a war crime. Based on this idea, Article 8 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC), states that acts of rape, sexual slavery, forced prostitution, and forced pregnancy constitute a criminal offense. Likewise, Paragraph F of Article 7, Paragraph 2, stipulates that sterilization and any form of sexual violence are a violation of the Geneva Conventions (Comité Internacional de la Cruz Roja [CICR], 2016).

The Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions of 1949, regarding the protection of victims of international armed conflicts (1977), in its Article 75, sustains that acts against human dignity, humiliating and degrading forced prostitution and any attack on modesty are prohibited. Article 76 of Protocol I of Geneva, also states that women are protected against acts of rape and forced prostitution, which is also declared in Article 27 of the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949 (CICR, 2016).

Based on these stipulations, the violations committed during an armed conflict and associated with armed conflict are considered war crimes; this means that sexual violence always constitutes an infraction of the instruments of human rights (CICR, 2014). Therefore, acts of sexual exploitation and abuse are infractions of IHL and international human rights norms or both (UNGA, 2005).

In this line, it must be noted that the UN peacekeepers' behavioral regulations provide for express compliance with the guidelines of IHL and the application of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as essential standards of action (DPKO, 2016). Moreover, the document, Observance by United Nations Forces of International Humanitarian Law, specifies, in Section 1.1, that the fundamental principles and norms of IHL will apply to the UN forces when they actively participate in situations of conflict (UNSG, 1999).

Therefore, when considering sexual violence as a war crime, the immediacy is to consider the primacy of International Law (IL). This affirmation is based on the recognition of the obligation through a legislative act and fulfillment of the application of the IL norms (Kelsen, 1960/1982). There are two theses: 1) primacy of the state legal order and (2) primacy of the international legal order. The first thesis states that the basis of the validity of IL must be found in the state legal order, which supposes that "the primacy of the legal order of the State itself, which means that the sovereignty of the State is assumed (...)" (Kelsen, 1960/1982). In other words, the sovereignty of the State is the condition or the decisive factor for the thesis of the primacy of the state legal order. This implies that IL is not considered as an "order placed above," but as a "legal order delegated" by the state legal order. That is "(...) international law only applies to the State when it is recognized by it" (Kelsen, 1982).

The second thesis affirms that the validity of IL starts from the principle of effectiveness that determines the foundations of this validity, as well as the territorial, personal, and temporal validity domains of the state legal orders. Therefore, the particular state's legal orders are delegated, hence, subordinate and committed to IL (Kelsen, 1960/1982, 1949/1995).

In short, based on the conception of IL as a valid and superior legal order, "then the concept of State cannot be defined without reference to international law" (Kelsen, 1960/1982, p. 341). In this context, the first thesis is dismissed; the elimination of IL is assumed by recognizing that the IL is only valid by its recognition by the State (Kelsen, 1960/1982). Thus, the second thesis, in which the international legal order supposes the existence of national orders and their superiority, is accepted (Kelsen, 1949/1995).

Based on the previous, the Draft Declaration on Rights and Duties of States of 1949 states in Article 13 that States have an express duty to fulfill, in good faith, the obligations arising from treaties and other sources of international law, which underlines the non-invocation of state provisions or laws "as an excuse to stop fulfilling this duty." Furthermore, Article 14 provides that States must conduct their relations with other States based on IL and that the principle of sovereignty is subordinated to the supremacy of IL (UNGA, 1949). Similarly, the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties of 1969 states, in its Article 27, that no State may invoke the provisions of domestic law as justification for non-compliance with a treaty (UN, 2009).

In light of the above, acts of sexual exploitation and abuse in the CAR must be judged by international humanitarian law and IHL, to ensure that the fundamental principles and customary rules are applicable and observed (Bouvier, 2007). Thus, there must be intensive cooperation with the International Red Cross (ICRC) and the application of the Geneva Convention of 1864, the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949, the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court of 1998, the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and the two Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions of 1949. This will be possible through mixed courts in which the weight of international regulations is applied to peacekeepers and the civilian population to "fight against crimes, whatever the legal status of the alleged offender" (UNGA, 2006, p. 13).

Conclusion

The main question is: must acts of sexual violence against civilians by peacekeepers in post-conflict zones be judged by IHL? The fact is that the presence of peacemakers is no guarantee that violence will not exist, given that, in post-conflict zones, a process is being carried out to cement a peace process and build a governmental authority for the transition through peaceful means of the parties in conflict. However, all of these efforts do not guarantee that there will not be physical violence against peacemakers by insurgent groups or sexual violence by peacekeepers against civilians.

This statement suggests that peacemakers must, necessarily, be instructed and put into practice the principles of IHL because the Member States to which they belong are part of the Geneva Convention of 1949. Two points must be considered: a) compliance and the protection of peacekeepers; and b) the measures implemented by the UN to prevent and suppress non-compliance with the provisions of the Geneva Convention and its Additional Protocols.

This allows us to consider two essential premises to answer the question: 1) the UN must consider the regulations and agreements with the contributing States in peace operations, and (2) sexual violence must be reconsidered as a serious fault of the human rights international regime. The first issue is to implement the so-called Red Cross Clause, according to which peacekeepers must observe the principle and spirit of IHL applicable to the conduct of military personnel, which makes them subjected to IHL.

The second issue is to consider sexual violence as a clear violation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; making it possible to point out that, by depriving civilians of security, sexual violence is not a disciplinary offense but a war crime. For their part, the Geneva Convention, the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, and IHL consider sexual violence an infraction of International Conventions that must be punished and, at the same time, constitute acts of torture that generate psychological suffering and attempt against personal physical integrity.

In sum, UN peacemakers from the contributing States are subject to IHL; this demands training, practice, and observance, which ratifies that non-compliance will result in the violation of the Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols.

Disclaimer

The authors state that there is no potential conflict of interest related to this work. This article is the result of research carried out within the framework of the course, Introduction to the Study of the United Nations System (directed by Dr. Miriam Estrada-Castillo) belonging to the Master's Degree in Conflict Resolution, Peace, and Development of the University for Peace (UPEACE).

About the authors

Jaime Edgar Maximiliano Jiménez Villarreal holds a Master's Degree in Social Sciences with a minor in Political Science from the Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales (Flacso), Ecuador. He is a general procurator and a research professor at the Universidad Politécnica Estatal del Carchi (UPEC).

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0899-1788 - Contact: edgar.jimenez@upec.edu.ec

Daniel Andrés Jiménez Montalvo holds a degree in International Relations and Integration from the Universidad Federal de la Integración Latinoamericana (Unila). He holds a Master's Degree in Conflict Resolution, Peace, and Development from the Universidad de la Paz (UPEACE). He is a research professor of the Foreign Trade at the Universidad Politécnica Estatal del Carchi (UPEC).

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9973-0502 - Contact: daniel.jimenez@upec.edu.ec

REFERENCES

AIDS-Free World (AIDS-FW). (2015). The UN's dirty secret: The untoldstory of Anders Kompass and Peacekeeper sex abuse in the Central African Republic. Recuperado de http://www.codebluecampaign.com/. [ Links ]

Amnesty International (AMIN). (2015). CAR: UN troops implicatedin rape of girlandindiscriminate killings must be investigated. Recuperado de https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2015/08/car-un-troops-implicated-in-rape-of-girl-and-indiscriminate-killings-must-be-investigated/. [ Links ]

Amnesty International (AMIN). (2016). Central African Republic: Mandated to protect, equipped to succeed? Strengthening Peacekeeping in Central African Republic. Retrieved from https://www.amnesty.org/es/documents/afr19/3263/2016/en/. [ Links ]

Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas (UNGA). (1949). A/RES/375 (IV). New York: Naciones Unidas. Retrieved from https://undocs.org/es/A/RES/375(IV). [ Links ]

Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas (UNGA). (1996). A/51/306 [Informe Manchel ]. Recuperado de http://bit.ly/2JbC0sC. [ Links ]

Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas (UNGA). (2000). A/S-23/10/Rev.1. Recuperado de http://bit.ly/2PV1ifm. [ Links ]

Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas (UNGA). (2005) A/59/710 [Informe Zeid ]. New York: Naciones Unidas . [ Links ]

Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas (UNGA). (2006). A/60/980. New York: Naciones Unidas . [ Links ]

Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas (UNGA). (2016a). A/71/818. New York: Naciones Unidas . [ Links ]

Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas (UNGA). (2016b). A/71/99. New York: Naciones Unidas . [ Links ]

Bouvier, A. A. (2007). Derecho internacional humanitario y la ley del conflicto armado (1.a ed.). Williamsburg: Instituto para Formación en Operaciones de Paz. [ Links ]

Bruneteau, B. (2008). O Etnicimo Genocidário do Pós-Guerra Fria e o Advento de uma Jurisdicáo Internacional Permanente. En B. Bruneteau (Ed.), O Século dos Genocidios: Violencias, massacres e Processosgenocidiários da Arménia ao Ruanda (pp. 229-266). Lisboa: Instituto Piaget. [ Links ]

Chonghaile, C. (2016). Head of UN mission in Central African Republic pledges to end troop abuses. The Guardian. Recuperado de https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/may/26/head-un-mission-central-african-republic-pledges-end-troop-abuses-minusca-parfait-onanga-anyanga. [ Links ]

Comité Internacional de la Cruz Roja (CICR). (2014). Violencia sexual en conflictos armados: preguntas y respuestas. Génova: CICR. [ Links ]

Comité Internacional de la Cruz Roja (CICR). (2016). Los crímenes de guerra según el Estatuto de Roma de la Corte Penal Internacional y su base en el derecho internacional humanitario. Recuperado de http://bit.ly/2vTTvFa. [ Links ]

Consejo de Seguridad de las Naciones Unidas (UNSC). (2016). S/2016/824. New York: Naciones Unidas . [ Links ]

De la Torre, F. B. (2016). Nuevos hitos en la lucha contra la explotación y abusos sexuales perpetrados por Peacekeepers. Recuperado de http://www.ieee.es/temas/conflictos-armados/2016/DIEEEA31-2016.html. [ Links ]

Departamento de Operaciones de Mantenimiento de la Paz (DPKO). (2016). Políticas y orientación adicionales. Recuperado de https://research.un.org/es/docs/peacekeeping/resources. [ Links ]

Deschamps, M., Jallow, H. B., & Sooka, Y. (2015). Takingaction on sexual exploitation and abuse by Peacekeepers: Report of an independent review on sexual exploitation and abuse by International Peacekeeping Forces in the Central African Republic. Recuperado de http://bit.ly/2Hb1mDD. [ Links ]

Hobbes, T. (1651/2012). Leviatá ou Matéria, Forma e Poder de um Estado Eclesiástico e Civil (2.a ed.). Sao Paulo: Martin Claret. [ Links ]

Human Rights Watch (HRW). (2016). ONU: es necesario acabar con los abusos sexuales cometidos por las tropas de paz. Recuperado de https://www.hrw.org/es/news/2016/03/08/onu-es-necesario-acabar-con-los-abusos-sexuales-cometidos-por-las-tropas-de-paz. [ Links ]

Jennings, K. M., & NikoliC-Ristanovic, V. (2009). UN peacekeeping economies and local sex industries: Connections and implications". Microcon Research Working Paper, 17, 1-29. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1488842. [ Links ]

Jiménez, X. (2012). Perspectiva de género en operaciones de paz de Naciones Unidas (2.a ed.). Williamsburg: Instituto para Formación en Operaciones de Paz . [ Links ]

Kaldor, M. (1999/2001). Las nuevas guerras: violencia organizada en la era global (1.a ed.). Barcelona: Tusquets Editores. [ Links ]

Kelsen, H. (1949/1995). Derecho nacional y derecho internacional. En H. Kelsen (Ed.), Teoría general del derecho y del Estado (2.a ed., pp. 390-462). México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [ Links ]

Kelsen, H. (1960/1982). Estado y derecho internacional. En H. Kelsen (Ed.), Teoría pura del derecho (1.a ed., pp. 323-348). México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México . [ Links ]

Kent, V. (2005). Peacekeepers as perpetrators of abuse: Examining the UN's plans to eliminate and address cases of sexual exploitation and abuse in peacekeeping operations. African Security Review, 14(2), 85-92. [ Links ]

Kompass, A. (2015). Dealing with reports of pedophilia by French Troops in the Central African Republic. Retrieved from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/514a0127e4b04d7440e8045d/t/55660871e4b086598604d7f9/1432750193924/04-2+-+Statement+by+Anders+Kompass%2C+OHCHR+-+March+29%2C+2015.pdf. [ Links ]

Koyama, S., & Myrttinen, H. (2007). Unintended consequences of peace operations on Timor Leste from a gender perspective. En C. Aoi, C. de Coning, & R. Thakur (Eds.), Unintended consequences of peacekeeping operations (1.a ed., pp. 23-43). Tokyo: United Nations University Press. [ Links ]

Laville, S. (2016a). Child sex abuse whistleblower resigns from UN. The Guardian. Recuperado de https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jun/07/child-sex-abuse-whistleblower-resigns-from-un. [ Links ]

Laville, S. (2016b). UN troops 'abused at least eight women and girls' in Central African Republic. The Guardian. Recuperado de https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/feb/04/un-troops-abused-least-eight-females-central-african-republic. [ Links ]

Laville, S. (2016c). UN whistleblower who exposed sexual abuse by peacekeepers is exonerated. The Guardian. Recuperado de https://www.whistleblower.org/in-the-news/guardian-un-whistleblower-who-exposed-sexual-abuse-peacekeepers-exonerated/. [ Links ]

Martin, S. (2004). Sexual exploitation in Liberia: Are the conditions ripe for another scandal? Recuperado de https://reliefweb.int/report/liberia/sexual-exploitation-liberia-are-conditions-ripe-another-scandal. [ Links ]

Naciones Unidas (UN). (1945). Carta de las Naciones Unidas y Estatuto de la Corte Internacional de Justicia. Recuperado de https://www.un.org/es/documents/icjstatute/. [ Links ]

Ross, A. (2016). Angelina Jolie says UN undermined by sexual abuse by peacekeepers. The Guardian. Recuperado de https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/sep/08/angelina-jolie-un-peacekeepers-special-envoy. [ Links ]

Secretaría General de las Naciones Unidas (UNSG). (1999). Observancia del derecho internacional humanitario por las Fuerzas de las Naciones Unidas. New York: Naciones Unidas . [ Links ]

Themnér, L., & Wallensteen, P. (2014). Armed conflicts, 1946-2013. Journal of Peace Research, 51(4), 541-554. [ Links ]

UN finds more cases of child abuse by European troops in CAR. (2016). The Guardian. Recuperado de https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jan/29/un-finds-more-cases-of-child-abuse-by-european-troops-in-car. [ Links ]

United Nations (UN). (2009). Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (with annex) Concluded at Vienna on 23 May 1969. En United Nations (Ed.), Treaty Series: Treaties and International Agreements registered or field and recorded with the Secretariat of the United Nations (Vol. 2319, pp. 332-512). New York: United Nations. [ Links ]

Webel, C. (2007). Introduction. En J. Galtung & C. Webel (Eds.), Handbook of peace and conflict studies (1.a ed., pp. 3-13). Abingdon: Routledge. [ Links ]

Zawati, H. (2007). Impunity or immunity: Wartime male rape and sexual torture as a crime against humanity. Torture, 17(1), 27-47. [ Links ]

3Report by Prince Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, at the time.

43 Ex-Director of Field Operations and the Technical Cooperation Division in the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).

How to cite: Jiménez Villarreal, J., & Jiménez Montalvo, D. (2019). Sexual violence in post-conflict zones: Reflections on the case of the Central African Republic. Revista Científica General José María Córdova, 17(27), 505-523. http://dx.doi.org/10.21830/19006586.436

The articles published by Revista Científica General José María Córdova are Open Access under a Creative Commons license: Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives.

Submit your article to this journal: https://www.revistacientificaesmic.com/index.php/esmic/about/submissions

Received: March 19, 2019; Accepted: June 02, 2019; Published: 2019

texto em

texto em