Introduction

Unquestionably, a characteristic of the contemporary international scenario is the spread of Violent Non-State Actors (VNSAs), defined by Podder (2012, p.6) “as groups a) willing and able to use violence to achieve their goals, b) not integrated into formalized state institutions, c) in possession of certain degrees of autonomy concerning politics, military operations, resources, and infrastructure (although they can be supported by a state actor, official, or other players obtaining personal benefits from this support), and d) whose organization or structure exists for a specific period”.

In addition to the power and influence these actors hold over wars or peacebuilding processes, they make large profits from markets, exploiting economies and controlling territories, making it necessary to negotiate agreements that offer political, socio-economic, or judicial concessions to neutralize their illicit activities (Felbab-Brown, 2020). However, Cockayne (2013) argues that the effectiveness of any efforts to resolve armed conflicts will depend particularly on one feature that policymakers misunderstand: criminal agendas, “programs, or plans of an underlying criminal nature conducted by actors competing for government and public management of state resources. These agendas can be adopted by a wide range of actors, such as criminal groups, insurgents, companies, public officials, and political leaders. Depending on the context, individuals and groups can take on both strategies and roles (political and criminal)” (Boer & Bosetti, 2017, p.9).

Thus, the following dilemma arises: given the need to generate optimal conditions for a peace process aimed at establishing procedures, norms, and institutional environments that recognize the preferences and interests of VNSAs, thus preventing possible sabotage or breakdown (Hoffman &: Schneckener, 2011), the outcomes will only be sustainable as long as they continue to be a part of a negotiation process, which implies a long-term commitment, especially during the implementation of the agreements.

For the past decade in Latin America, insurgencies, criminal groups, and gangs have participated in government authority-promoted negotiations, where an inadequate treatment of criminal agendas has made the difference between lasting peace and continuous agitation (Cockayne, 2013). Given this scenario, it is worth asking: How do criminal agendas influence a pacification process with VNSAs? This article aims to resolve this question by presenting a qualitative analysis of the gang truce in El Salvador with the help of the Peace Triangle as an analytical framework based on three study variables: issues, behavior, and attitudes.

The peace accord reached between Mauricio Funes’ administration and the two main criminal gangs operating in the country, Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and Barrio 18 from 2012 and 2013 after heavy military combat was selected as a case study for its relevance in terms of lethality, the diversity of actors involved, and its scope. The analysis of the gang truce aims to make a double contribution to peace studies. On the one hand, it fills a gap in academic knowledge about the sustainability of peace processes. On the other, it addresses the relationship between criminal agendas and conflict resolution. From this angle, this study hypothesizes that the inadequate management of the criminal agendas by the former Salvadoran president transformed the peace negotiation into a strategy of damage control, as it did not intend to modify the scale of predatory crimes committed by gangs, but rather to shape its behavior: low profile, without a confrontational posture, and exhibiting reduced levels of lethality.

Thus, the methodology used in this article is a case study with a diachronic approach. It examines a limited period in depth so that the competition of state and nonstate actors is analyzed according to their relevance within the indicated context. Also, an intentionally non-probabilistic sampling was used, focused on events over which there is no control; they are examined with a holistic approach, while the observation unit is studied in its entirety. Consequently, this research has a non-experimental character that is classified as transectional, as it aims to evaluate the level or status of many variables at a given time.

The research relies mainly on secondary sources to analyze the peace process, particularly academic articles and books by known authors. Tertiary resources contained in national and international databases were also used, such as Conflict Barometer, created by the Heidelberg Institute for International Conflict Research (HIIK), and InfoSegura, a charge of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and the United States Development Agency (USAID) in El Salvador. In addition, reports prepared by non-governmental organizations, such as the International Crisis Group, were examined. Information was also gathered from primary sources, particularly joint statements issued by MS-13 and Barrio 18 leadership and interviews granted by unofficial intermediaries and government officials during the peace accord.

Following the investigative hypothesis, lethal violence was measured through homicide and predatory crime based on the extortion rate generated by National Civil Police. This illicit activity constitutes primary tool of socio-economic and territorial control used by the VNSAs analyzed in this case (gangs). In addition, the victimization survey published by the Institute of Public Opinion of the Central American University (IUDOP) was examined to measure the social perception of the evolution of public security conditions during the negotiation.

The article is structured as follows: the Peace Triangle is presented as an analytical model in the first section. Then, the negotiation process during the Funes administration is analyzed in terms of the vertices of the Peace Triangle, showing the changes in behavior and attitudes of its protagonists concerning the criminal agendas of MS-13 and Barrio 18. Finally, conclusions are drawn based on each variable considered in the theoretical framework.

The Peace Triangle as an analytical framework

Defining the concept of peace is complex due to its polysemic character; however, the specialized literature refers to a helpful distinction between two interpretations. The first one is a restricted vision of the term that alludes to the absence of war and direct violence (applied by an actor), also known as negative peace (Galtung, 1996). However, the existence of conflicts in a society cannot be ruled out; thus, negative peace is understood as a condition in which multiple actors can have antagonistic relationships expressed in confrontations that exclude the use of armed, systematic, and organized violence.

The methodological strength of this conceptualization is that it allows its quantification based on metrics or indicators, making it easily measurable. From this angle, peace can be observed in a country through the lethality rate recorded yearly, for example. However, this notion has been questioned for two reasons. First, its narrowness leads to reductionist interpretations whereby relations could only be described as peaceful or conflictual. Second, this conception lacks explanatory power concerning the nature, strength, and sustainability of peace (Diehl, 2016), thus, making it difficult to understand why peace is stable and lasting in some nations while very difficult to preserve in others.

A second alternative approach emerges in response to this bump, positive peace. This holistic definition contemplates the absence of indirect or structural violence (that is not exercised or applied by an actor) expressed in the existence of social justice, cooperative relations, and full respect for human rights. In other words, by delimiting its specific characteristics, this concept seeks to understand in-depth factors that contribute to a solid peace, opposing its negative meaning. From this perspective, Joshi & Wallensteen (2018) argue that positive peace can be operationalized through five analytical dimensions: (1) well-being; (2) quality of relationships; (3) conflict resolution; (4) access to resources, equity, and human security; and (5) institutional capacity. Thus, these elements allow a state to be classified as peaceful in terms of positive peace.

Likewise, this vision has been the target of criticism mainly because the incorporation of dimensions such as social justice or human rights broadens the object of study of the discipline to the point that the concept of peace loses its usefulness as an analytical category, generating a conceptual stretch. In response, proponents of positive peace indicate that “the mere absence of war can be compatible with situations in which there is a profoundly authoritarian and unjust status quo that sooner or later would lead to an outbreak of violence” (Harto de vera, 2016, p. 130). Therefore, they believe it is necessary to understand the causes of armed confrontation and analyze how sustainable peace can be developed, and what factors can prevent the recurrence of violence.

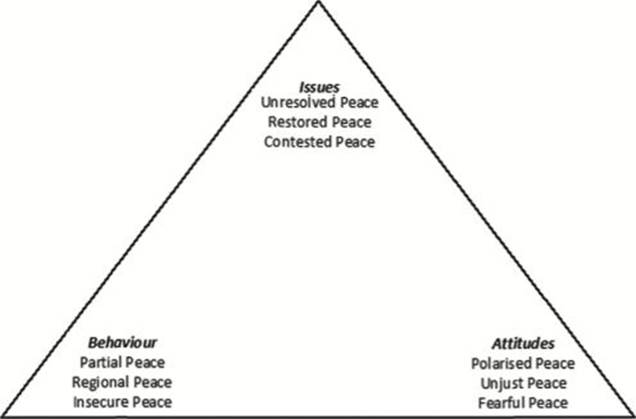

Thus, this research project uses the contribution by Hoglund & Soderberg (2010), who, to operationalize the sustainability of peace processes, designed an analytical model known as the Peace Triangle, an instrument that evaluates the peace processes through three dimensions: issues, behavior, and attitudes (see Figure 1). First, however, it must be clarified that each one has its own logic, giving shape to a triangle in constant evolution, where they all influence each other.

The first element refers to the topics at stake or the incompatibility of interests. Naturally, a crucial aspect of this element is the willingness of the protagonists of the confrontation to articulate or pursue their goals. This component evaluates the relative presence or absence of conflicting issues. The second element refers to the means used by the conflicting parties to pursue their conflicting interests, including physical violence, intimidation, boycotts, or sanctions. Actors execute these actions to force the opponent to give up or modify his objectives. This component also considers the relative presence or absence of violence and insecurity during the peace process or post-conflict. The third element constitutes an indicator of psychological conditions (emotions, desires, will, or perceptions) that are developed between the parties in conflict and can include prejudices, stereotypes, and feelings of distrust and fear also derived from the conflict or reinforced by it (Höglund & Söderberg, 2010, pp. 374-379).

Based on these three indicators, the authors developed a set of categories to construct multiple scenarios that could occur during a peace process, which are not mutually excluding, given that societies may present some of these features simultaneously, as discussed below.

Concerning the first component of the triangle (issues), they projected an unresolved peace (the process only contributed to diminishing or stopping armed violence but failed to resolve the conflicts main problems), restored peace (certain issues of the conflict were resolved in the peace process but underlying causes remain unsolved), or contested peace (agreements reached or new post-conflict order give rise to issues that may generate a new armed conflict).

Regarding behavior, the authors categorized a partial peace (actors, ex-combatants, or dissident factions use violence to enforce concessions during the peace process or express their discontent with the peace agreement’s terms and conditions; this scenario does not necessarily imply the reactivation of the armed conflict), regional peace (new outbreaks of violence of varying intensity occur in some zones or geographic areas, despite the signing of the peace agreement), or insecure peace (a high level of criminality and violence is registered during the post-conflict phase).

Concerning attitudes, the authors distinguished between polarized peace (the actors’ attitudes are radicalized during the peace process), unjust peace (during the peace process, the society perceives its situation as disadvantageous concerning one of the actors, either because of impunity or injustice), or fearful peace (after the war, the society is intimidated due to the repression and control of the current regime). However, it should be noted that the Peace Triangle was not designed to cover all aspects of a peace negotiation but rather constitutes a model to identify scenarios that the process might generate (Höglund & Söderberg, 2010, pp. 375-386).

Analysis based on the Peace Triangle

The following section breaks down the three dimensions analyzed to evaluate the gang truce between Mauricio Funes’ administration and the two main criminal gangs operating in the country, Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and Barrio 18.

Issues

The Chapultepec Peace Accords ended an armed confrontation between the Salvadoran military government and the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN) guerrillas, which resulted in approximately 70,000 deaths and 1,000,000 displaced people (ICG, 2017). However, that milestone marked the beginning of a transition to a new cycle of violence. By the end of the 1990s, the U.S. government aggressively deported thousands of ex-convicts to Central America’s northern triangle (Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador). Members of rival street gangs, Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and Barrio 18, returned to the country in a post-conflict scenario marked by institutional weakness, a broken social fabric, and a destroyed economy, conditions that aided their quick expansion.

Until the beginning of the 2000s, the Salvadoran government paid little attention to the gangs, allowing them to operate with a certain degree of freedom. However, a few months before the presidential elections, where a resounding defeat of the ruling Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA in Spanish) party was in sight, then President Francisco Flores (1999-2004) launched the Mano Dura policy, pointing to these criminal groups as allegedly responsible for an outbreak of crime and violence that was supposedly affecting the small Central American country (ICG, 2017). However, official figures refitted that thesis: at the time, El Salvador was going through the calmest period since the end of the counterinsurgency war, and violent deaths attributable to gangs represented about 10% of the national total (Aguilar, 2019, p. 24).

The first anti-gang strategy was designed with an electoral zeal typical of punitive populism:, as evidenced by the fact that its launch was accompanied by a narrative that misrepresented its power and influence, ignoring its socio-economic origin (Hernandez- Anzora, 2017). The demonization of the maras responded to a dynamic between electoral supply and demand, conditioned by the legacy of authoritarianism left by the armed confrontation, and reflected in some elements of the Salvadoran political culture, such as the discourse on crime (Amaya, 2017). Consequently, it is possible to say that former president Flores approached the gang phenomenon by reproducing negative perceptions associated with the imaginary of the internal enemy, seeking to generate public anxiety.

This way, the president initiated a repressive effort against gangs through police raids aimed at “massively and indiscriminately capturing all those who, judging by their appearance, were presumed to be gang members” (Aguilar, 2019, p. 13). In addition, there was the application of controversial transitory legislation, later declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court on the grounds that it violated the Convention on the Rights of the Child (Wolf, 2017, p. 50). This approach allowed ARENA to win a presidential victory, which is why it continued its approach under the name Super Mano Dura, with a greater punitive emphasis but considering prevention and rehabilitation components: Mano Amiga and Mano Extendida, aimed at youth in vulnerable situations and incarcerated youth, respectively. However, the low investment, the delay in its implementation, and the reduced number of participants affected and reduced its scope (ICG, 2017, p. 16).

This harassment induced a sophistication of gang activity in response to the crusade undertaken by the government. Paradoxically, the allocation of prisons by membership made it possible to centralize operations, strengthen group cohesion, and manage the violence perpetrated by their cells in the streets through economies of protection (Lessing, 2017). The collection of extortion taxes was their main means of subsistence and an instrument of territorial control, enabling them to create a para-state in marginalized communities. In addition, this anti-gang policy accentuated the use of lethal violence in three directions: to reinforce internal discipline, attack rivals who contributed to their persecution, and intimidate the population that cooperated with the police (Reyna, 2017, p. 21). Consequently, this punitive strategy dramatically transformed gang behavior.

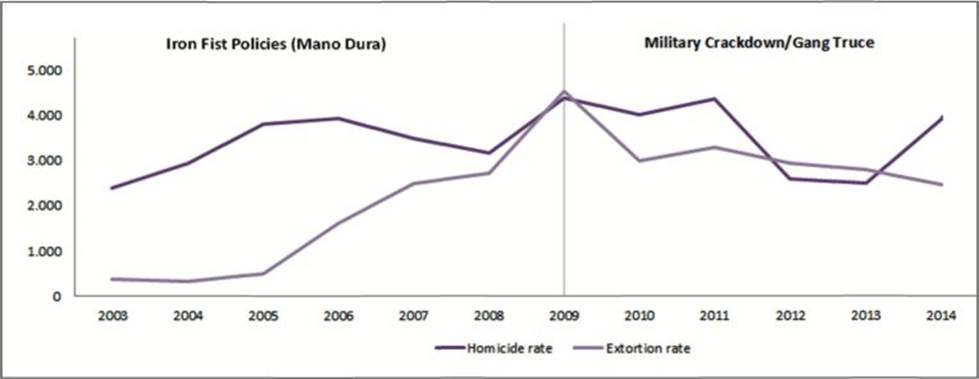

Although the Mano Dura policies were electorally profitable for the ruling party in the beginning, the public security crisis that followed their implementation led Salvadoran authorities to discontinue them progressively (Aguilar, 2019). During their enforcement, the homicide rate practically tripled, while the number of extortions increased 14 times, as seen in Figure 2. This, in addition to prison overcrowding caused by relentless criminal prosecution, as the number of prison inmates doubled (ICG, 2017, p. 10). Consequently, the official statistics more than demonstrated the ineffectiveness of these policies regarding the original objective: to combat violence and criminality associated with gangs, seriously compromising ARENAs continuity in the presidency.

Source: Created by author from PNC, 2020; USAID/PNUD, 2021.

Figure 2. Evolution of the homicide and extortion rates in El Salvador (2003-2014)

After the FMLN came to power with Mauricio Funes (2009-2014), anti-gang policy took an erratic course. Initially, recognizing the need for a comprehensive approach, the new president launched a National Security and Coexistence Policy focused on crime prevention, control, and repression; social reintegration; attention to victims; and institutional reform (Wolf, 2017, p. 230). However, the idea did not prosper because of 1) the lack of bureaucratic experience necessary to implement the planned changes; 2) the lack of inter-agency coordination to prioritize the lines of action; and 3) the collapse of police capacities in the face of a deterioration in the security situation reflected in an extreme homicide rate associated with gang activity (Van Der Bough & Savenije, 2013).

Naturally, the level of alarm among the Salvadoran population grew, as did questions about the inability of the new authorities to confront the public security crisis (Aguilar, 2019). This situation prompted the militarization1 of the fight against gangs, an option essential to demonstrate control and strength. Because 73.9% of the public opinion supported this option (IUDOP, 2009, p. 86), the government significantly increased the number of soldiers in the fight against crime, giving them greater functional autonomy, and expanding their powers and competencies (Amaya, 2012, p. 76). Therefore, military participation in public security went from being an exceptional resource to becoming a regular procedure. Between 2009 and 2014, the military personnel assigned to this sector increased 28%. During this period the Army participated in a wide range of plans (Aguilar, 2019, pp. 39-40)2, in contravention of the reforms achieved after the Chapultepec Accords.

A Law for the Prohibition of Gangs was also enacted, condemning their legalization, financing, and third-party collaboration. This action constituted more of a symbolic reaction to the public commotion, as instruments for their criminal prosecution already existed (Van Der Bough & Savenije, 2015, p. 166). Seeking to repeal the law and initiate a dialogue, the maras forced a two-day national public transportation strike that, “according to official figures, mobilized 60% of public transport, causing a 40% commercial activity drop in the main cities and a loss of around 24 million dollars” (Martinez, 2019). With this powerful gesture, they believed they had enough relevance to be heard as any other political actor (Cruz, 2013). Due to this, Defense Minister General David Munguía Payés requested that the maras were to be considered a serious security threat: “The gangs want to scare the population, show their strength. A democratic government like ours cannot negotiate with criminal organizations” (Martinez, 2019).

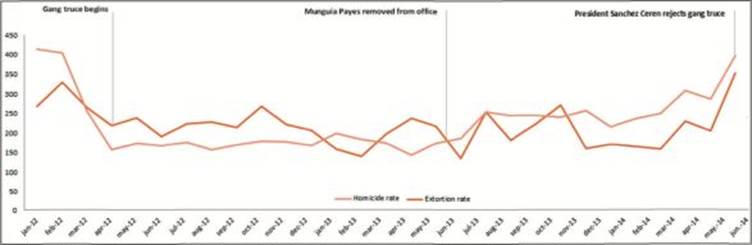

This discourse permeated the vision of the former Salvadoran president, causing a shift in his anti-gang policy: to intensify the repressive effort. As a result, in November 2011, Munguia Payes took over the Ministry of Public Security, blaming the maras exclusively for 90% of the murders, dismissing the impact of other criminal actors on the lethality rate (Vasquez & Marroquin, 2014). Based on this premise, the new minister promised to reduce homicides by 30% in one year, telling the press that to achieve this goal, he was preparing a massive repression scheme (Aguilar, 2019). Nonetheless, violence continued to rise, as shown in Figure 2, demonstrating the ineffectiveness of militarization in combating gangs and forcing the Funes administration to modify its strategy, opting for the path of agreements. This is also confirmed by the trends expressed in Figure 3.

Source: Created by the author from PNC, 2020; USAID/PNUD, 2021.

Figure 3. Monthly evolution of homicide and extortion rates during the gang truce

Although it is estimated that the agreement would have saved 5,501 lives (Katz & Amaya, 2015, p. 43), its detractors argue that it would have allowed rival gangs, MS-13 and Barrio 18, to expand geographically, dividing up the disputed areas without the need to resort to aggression or assassinations, generating an undesirable result: consolidating a pax mafiosa in Salvadoran territory (Felbab-Brown, 2020, p. 33). This problematic scenario also hindered the execution of the sanctuary municipalities project because these criminal groups never relinquished control over their domains. This is evidenced by the fact that extortions varied only 5% during the term of the pact, as shown in Figure 3.

Without a source of funding or alternative means of subsistence, it was difficult to think that the gangs would stop taxing communities under their control. Moreover, there was a strategic dilemma that prevented them from stopping extortion, as Adam Blackwell explained in an interview with the digital newspaper El Faro: “[It was impossible to demand that these groups give up] their main source of power if the government remained on a war footing, because it would be illusory to ask them to surrender and then be executed by the enemy” (Sanz, 2012). His statement suggests that the maras never had any real intention of making commitments to their criminal agenda, such as abandoning illicit activities (Cockayne et al. 2017).

For this reason, it is possible to say that the negotiated pacification process with the gangs never achieved social legitimacy and that there was a high degree of skepticism among the Salvadoran population regarding its true impact or supposed positive externalities in daily life (FUSADES, 2013, p. 123). In fact, this situation was clearly reflected in public opinion polls conducted during the gang truce, which also did not indicate significant improvements in victimization rates. Thus, in December 2012, 19.9% of those surveyed said they had been victims of a crime in the past year. While in the same period of 2013, this figure reached 20.5%, an increase of 0.6% (USAID/PNUD, 2021).

The discovery of 97 clandestine graves by the Institute of Legal Medicine raised doubts on the veracity of the drop in homicides (HIIK, 2014, p. 82). Cruz & Duran- Martinez (2016) suggest that such a situation would indicate a hypothetical capacity of the maras to strategically manipulate the visibility of the violence3, looking to make a convincing simulation of compliance with the agreement. Thus, the gangs would have concealed the killings to avoid attracting repressive state efforts and implying a deceptive reduction of homicidal violence. In this sense, it is worth noting that during the truce, the rate of missing people rose from 39.3 to 54.5 per 100,000 inhabitants, an increase of 38.7% (USAID/PNUD, 2021). Therefore, the negotiated solution was a damage control strategy, as it did not seek to modify the scale of predatory crimes committed by the gangs but rather to control their behavior: low profile, without a confrontational stance, and exhibiting moderate levels of lethality.

Behavior

The Funes administration proved incapable of structuring a congruent narrative about the gang phenomenon -beyond its criminal nature- that would allow for the validation of the pacification process as a viable option to solve the public security crisis and to reach common minimums among the population to guarantee its sustainability. Under this logic, it is worth mentioning that the lack of transparency about its role in the dialogue exposed the Salvadoran government to ethical questions associated with an alleged corruption of the bureaucratic apparatus as, by deciding to negotiate with the maras, it was breaking its anti-gang legislation, setting a bad precedent on the rule of law in the small Central American country.

However, it should be noted that the intelligence services informed former President Funes and Munguía Payés about possible dialogue risks, thus increasing transparency (Felbab-Brown, 2020, p. 29). From this angle, it is worth remembering that the exploratory contacts with both gangs (MS-13 and Barrio 18) were developed stealthily by the unofficial mediators to facilitate consensus building at an early stage, as well as to prevent government authorities from being compromised or singled out in the event of failure. Fabio Colindres and Raul Mijango led the team in charge of doing good offices and reporting the progress of the negotiations, whose profiles inspired confidence in the counterpart: the moral authority of the former military chaplain and the honorability of the recognized former guerrilla commander.

Had the negotiations been known in their early stages, they would surely never have prospered due to the strong public repudiation of the very idea of making a pact with the community’s main public enemy: the maras, a perception created by the Salvadoran establishment and reinforced by negative media coverage. Therefore, a communications strategy was needed to tie up loose ends, close the flanks of attack, or mitigate the collateral damage caused by the publication of the report in the independent newspaper El Faro, which detailed the negotiation process and subsequent transfer of some thirty members of the largest groups from the maximum-security prison Zacatecoluca to prisons with fewer restrictions (Felbab-Brown, 2020, p. 29). Even so, the dialogue process continued.

At the beginning of the peace process, Mauricio Funes found himself in a difficult position due to the erratic course of his anti-gang policy, reflected in the failed attempt to install a comprehensive approach and the counterproductive militarization of its combat. In addition, the weakness, corruption, and inefficiency of the Salvadoran security forces hindered the implementation of his approach. Meanwhile, the maras already exercised tight territorial and socioeconomic control, replacing the state in providing basic services: their members and the dominated communities were totally merged (Felbab-Brown, 2020, p. 12). Moreover, while the gangs allowed their cells or clicas to act with a certain degree of autonomy, the leaders possessed a high capacity for command and cohesion that allowed them to better negotiate.

This cohesion was demonstrated by the abrupt drop in murders observed as soon as the truce began to be in force and the capacity to maintain it relatively stable for 15 months, thus contributing to improving public security conditions during its duration, which was the gangs’ main negotiating tool with the Salvadoran government. However, the loss of control of the gang leadership in prison over the actions of the clicas on the outside, after the blocking of the communicating vessels, prevented them from continuing to regulate homicidal violence. Even so, the gangs were in a position of strength due to their size, geographic reach, and social capital, having enough capacity to seal or implement agreements. Moreover, the involvement of the two main maras (MS-13 and Barrio 18) neutralized the risk of possible sabotage by adversarial groups.

Unlike the Salvadoran government, which left the negotiations in the hands of third parties, taking away their official character, the two main gangs were negotiating from a position of leadership. However, it should be emphasized that both negotiating teams were legitimate and representative and had a direct channel of communication with their counterpart. For this reason, it was to be expected that the agreements reached would be sufficiently forceful to be accepted by both sides. Although the gang leaders’ demands were reasonable, including improved prison conditions and implementation of social intervention projects in their communities, certain concessions made were difficult to assimilate, such as the omission of an anti-gang legal framework or the withdrawal of the military from public security functions (Felbab-Brown, 2020, p. 18).

There are two points worth noting regarding the previous. On the one hand, crucial issues were not discussed during the dialogue, including the possible repeal or reform of anti-gang legislation, the granting of judicial benefits (amnesties or reduced sentences to gang members), and the implementation of mechanisms for reparations to their victims. The exclusion of these issues from the negotiation agenda was a normative and strategic error because “if you don’t hold the gangs accountable for their acts, you lose credibility with them” (Felbab-Brown, 2020, p. 33). In addition, it is necessary to mention that the agreement did not contemplate the dismanding of the maras, only the conditional cessation of their illicit activities within the framework of the sanctuary municipalities project, significantly reducing their potential for transformation. Yet again, we see that the pact was not conceived as a strategy for the sustained reduction of lethality but rather as a form of control and change of behavior.

On the other hand, it should be noted that, during the ceasefire, the Funes administration proved incapable of adequately managing the criminal agendas of the gangs, which is why the dialogue process led to the strengthening of these criminal groups as privileged interlocutors with the Salvadoran government. This was reflected not only in the tenor of the concessions made by Munguía Payés but also in the fact that they flouted the conditions imposed by the government: they continued extorting communities under their control and committing murders underhandedly. Undoubtedly, the verification of the transgressions to what was agreed also influenced the change of strategy adopted by the next minister of public security, Ricardo Perdomo, thus truncating the process of pacification negotiated with the two main maras in El Salvador.

Attitudes

In 1992, the FMLN sealed a peace agreement with the military regime seeking to end a bloody civil war. Ironically, 20 years later, it was the government of the former Salvadoran guerrilla the first to negotiate a nationwide ceasefire with the largest gangs, given the meager results of the punitive policies implemented. However, the Funes administrations attitude became ambivalent, making it difficult to determine the real support of the bureaucratic apparatus for the pacification process. While Munguía Payés’ support for the negotiating team was vital to its progress, the fierce opposition of Attorney General Luis Martinez reflected a high degree of political dissidence. Moreover, when the talks aired, generating strong popular rejection, Mauricio Funes blamed the head of public security and the mediators.

This hesitant attitude prevented the Funes administration from transforming the agreement into a pacification strategy that would lead to a sustained reduction in criminal violence. Moreover, because the truce had mainly been motivated by the need to obtain benefits for the presidential elections, the government hesitated to assume it as its own, given its unpopularity, or to abandon it when Munguía Payés was removed as minister of public security. Consequently, the social polarization around the maras and their instrumentalization as an electoral tool influenced the decision to agree on a truce to reduce the high rates of homicidal violence.

Due to the widespread rejection caused by the pact, the next president, Salvador Sánchez Cerén, not only ruled out the possibility of continuing it under his administration but also redoubled repressive efforts against the gangs, despite having secretly negotiated the electoral support of these criminal groups in the run-up to the ballot. This was how his government sought to frustrate the incitement to new peace negotiations, criminalizing both the calls for dialogue and its promoters and mediators (Tabory, 2016). In fact, both Mijango and Munguía Payés would later be arrested and prosecuted on charges of unlawful association in the context of the truce agreed upon during Funes’ five-year term (Carlson, 2020).

During the first stage of the dialogue with the Salvadoran government, the gangs had a committed attitude because, although they used the negotiation process to further their criminal agendas, they maintained a high degree of self-criticism regarding their responsibility for the public security crisis. “The leaders in prison had a positive attitude and wanted to collaborate; they didn’t want to see their children make the same mistakes” (Felbab-Brown, 2020, p. 25). However, their attitude became distrustful when the Funes administration failed to comply with the conditions agreed upon, such as the abandonment of the sanctuary municipalities project, the obstruction of the negotiating teams efforts, and the military’s offensive launch after the abrupt departure of the truces architect.

Similarly, the truce led to a political awareness of the gangs based on the public ostentation of their monopoly of violence in relation to the legitimate government, using the homicide rate as a tool for negotiation, or, rather, for pressure (Hernandez-Anzora, 2017). Undoubtedly, another instrument used by these criminal groups was the territorial control accumulated during the implementation of sanctuary municipalities to the detriment of the sovereignty of the State in such areas, allowing them to tip the balance towards a specific candidacy and openly intervene in the results of an electoral process, as happened with the FMLN during the 2014 presidential runoff. From this angle, it should be noted that the exchange of bullets for votes in favor of political elites sponsoring their criminal agendas validated a corrupt symbiosis between the two, posing a serious risk to the legitimacy of the democratic system.

Nevertheless, it was possible to observe a certain political awareness when agreeing to the truce, as the gangs acted strategically, leaving aside their traditional enmity to strengthen their group cohesion based on a collective identity reflected in the ability to unify criteria on the contingency, speak with one voice through joint communiqués, or negotiate agreements that expressed common demands (Cantor, 2016). It is possible to affirm that the controversial pacification process with the government of Mauricio Funes allowed the largest gangs to dialogue and build mutual trust, demonstrated by their coordinated response to the re-launching of the military offensive by Perdomo.

On the other hand, the OAS showed a cooperative attitude, being the main international support for the negotiation process: it not only encouraged the promotion of dialogue between the MS-13 and Barrio 18 so that they would learn to communicate in a civilized manner, instead of resorting to assassinations or attacks, but they also sought to provide its expertise on conflict mediation in the technical committee created to address the root causes of the gang phenomenon. The will of the OAS to aid the process contrasted with the aggressive attitude of the U.S. government regarding the truce due to the size of the gang diaspora in its territory and the multiple economic and political-diplomatic efforts committed to combating them.

Conclusions

After analyzing the gang truce agreed upon during the Mauricio Funes administration (2009-2014) in El Salvador, using the Peace Triangle as an analytical framework, it is possible to draw conclusions based on its three study variables: issues, behavior, and attitudes and establish the effects of the maras’ criminal agenda on the peace process.

Regarding the issues variable, it is possible to state that the ceasefire agreed upon with the maras generated unresolved peace. That is, it failed to address the structural causes of the gang phenomenon, nor did it deliver licit livelihoods to the members of these groups. Additionally, their criminal responsibility and dissolution were never discussed in the negotiation agenda, a serious obstacle to progress towards their demobilization and reincorporation into civic life as the desired end state. The truncated peace process led to the strengthening of the main gangs (MS-13 and Barrio 18) based on their group cohesion, territorial control, and use of lethality as a means of pressure, which not only allowed them to continue their criminal activities from prison but also to demonstrate their great usefulness as political partners in Salvadoran democracy. This paradoxical result was largely because the ex-guerrilla government did not make the necessary efforts to modify the strategic calculus of these VNSAs, and because the maras saw the opportunity to strengthen their internal cohesion via the concessions made by the government.

Under this logic, while the pact with the gangs was in force, the Funes administration failed to design and implement a comprehensive and sustainable security strategy based on a multifaceted institutional presence and socioeconomic intervention in those communities dominated by the gangs. This step was important to replace the alternative governance schemes imposed by these criminal groups in most of the territory, mainly based on extortive tax collection. Thus, the government failed to demonstrate sufficient capacity to recover its authority at the local level, as its interaction with the maras covered a spectrum from confrontation to the construction of pragmatic alliances in the face of electoral situations. Therefore, it can be concluded that the truces failure prevented El Salvador from beginning a negotiated transition to a legitimate order and allowed the maras to continue growing locally because of the absence of proper governance.

In terms of behavior, the pact with the maras generated partial peace. The sudden drop in the homicide rate registered during its term would not necessarily imply an improvement in public security conditions. Rather, it indicated the persistence of a robust alternative governance that allowed the largest gangs (MS-13 and Barrio 18) to continue exercising territorial and socioeconomic control by resorting to their main criminal activity: extortion. This situation is confirmed by the slight variation in the victimization rate experienced during the truce. Thus, it is possible to point out that these VNSAs did not send signals of a genuine change in their criminal nature but only altered their behavior for tactical reasons, proving the investigative hypothesis. Therefore, the ceasefire was a damage containment strategy for the Salvadoran government as it did not seek to modify the scale of the predatory crimes committed by these groups, but rather encouraged low-profile behavior without a confrontational posture and moderate lethality. The government s strategy failed to produce sufficient conditionality as it was reluctant to use the public force necessary to surrender the maras’ will or seek to cease their capabilities. Therefore, the maras could use any staged behavioral changes that would earn them positive responses from the government. In other words, the incentives for behavioral change were never truly realized.

Similarly, the location of mass graves during the negotiation process suggests that the Funes administration acted with a high degree of condescension towards its counterpart, not only because of the nature of the prerogatives granted to the gang leadership but also because of its unwillingness to verify rigorous compliance with the commitments made, especially those referring to the ceasefire and the abandonment of their illicit activities in the framework of the sanctuary municipalities project. This shows that the former president used selective law enforcement to tolerate or simply manage gang violence. Only when Mauricio Funes went through a turbulent electoral situation was he forced to act sternly in the face of violations of the agreement, placing the continuity of the negotiated pacification in jeopardy. However, the Salvadoran government was also unable to offer the MS-13 and Barrio 18 minimum security conditions to continue with the peace process, as evidenced by the arrest and prosecution of its members by order of the highest national prosecutor.

In close relation to the above, it is possible to argue that the truce agreed upon with the maras -and the consequent decrease in homicides- did not constitute a sustainable pacification strategy because it depended on the authority exercised by the gang leadership over its external cells, as well as on the communicating vessels created by the negotiating team under the approval of Munguía Payés. Thus, this study showed that when the then minister Ricardo Perdomo dismantled the mediation structure and resumed the militarized combat against the gangs given the upcoming presidential elections, the pact made with the Funes administration was broken, along with the control over the murders committed by these criminal groups, generating an upturn in homicidal violence, and subsequent aggravation of the public security crisis in El Salvador.

Concerning the attitudes variable, it is possible to affirm that the peace process with MS-13 and Barrio 18 generated a polarized peace. During the preliminary contacts, the Funes administration and the gang leadership showed a pragmatic attitude, as both instrumentalized the negotiation process in terms of their agendas. The maras saw this as an opportunity to consolidate their political capital, reorganize their territorial presence and continue their illicit operations. In contrast, the Salvadoran government sought electoral gains associated with an improvement in the public security situation generated by the truce agreed with these criminal groups, even though a negotiated solution implied admitting its institutional weakness by transgressing the anti-gang legislation in force at the time.

However, after digital media leaked the agreed truce, the attitude of the ex-guerrilla government became ambivalent, which was reflected in its hesitation to assume it as a political option due to its unpopularity, explained by the existing social polarization around the maras, as well as the strong rejection expressed by the main benefactor of the Salvadoran State in terms of security, the United States, due to the economic and diplomatic efforts involved in its combat. Likewise, the government authorities’ hesitation prevented them from reaching agreements with the political elite, international organizations, and civil society regarding the sustainability of the pacification process, which resulted in a deficient implementation and financing of the sanctuary municipalities project. In other words, the fact that the government s incentives were placed on electoral gains meant the peace process was always a prisoner of both the mismanaged expectations of the administration and the continued structural weakness that allowed the maras to produce a competitive state at the local level, thus allowing the maras to control the result of the peace negotiation in their favor.

Finally, once the Supreme Court ruling decreeing the removal of Munguia Payes as minister of public security was issued, attitudes between the two sides became defensive. On the one hand, with a view to the presidential elections, the Funes government tried to mitigate the reputational damage caused by the truce with the largest gangs (MS-13 and Barrio 18), echoing the popular clamor: to break it and resume the frontal combat against these criminal groups. Meanwhile, the gangs, resentful of what they considered a violation of the agreement, opted to resort to homicidal violence as a means of protest for the re-establishment of the channels of dialogue with the new president, Salvador Sánchez Cerén. However, given the controversy generated by the peace process, the following government radicalized its position towards the gangs, penalizing them and their facilitators, despite having sought their electoral support during the runoff.