Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista de Relaciones Internacionales, Estrategia y Seguridad

Print version ISSN 1909-3063

rev.relac.int.estrateg.segur. vol.12 no.1 Bogotá Jan./June 2017

https://doi.org/10.18359/ries.2462

ARTÍCULO DE REFLEXIÓN

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18359/ries.2462

CHALLENGES OF ECONOMIC GLOBALIZATION*

DESAFÍOS DE LA GLOBALIZACIÓN ECONÓMICA

DESAFIOS DA GLOBALIZAÇÃO ECONÔMICA

Mauricio Lascurain Fernández**

*Este artículo de reflexión surge como parte de los trabajos desarrollados en la Academia de Estudios Internacionales de El Colegio de Veracruz.

** Doctor por la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, en el Programa de Nueva Economía Mundial, Maestro en Relaciones Internacionales por la Universidad de Essex del Reino Unido y Licenciado en Comercio Exterior y Aduanas por la Universidad Iberoamericana de Puebla. Se especializa en temas de política internacional, relaciones internacionales, globalización, análisis económico, inversión extranjera directa. Actualmente es Profesor-Investigador de El Colegio de Veracruz., Xalapa Veracruz, México. E mail: mlascurain@colver.edu.mx.

Referencia: Lascurain Fernández, M. (2016). "Challenges of economic globalization. Revista de Relaciones Internacionales, Estrategia y Seguridad. 12(1), pp. 23-50. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18359/ries.2462

Recibido: 5 de junio de 2016

Evaluado: 15 de julio de 2016

Aprobado: 19 de septiembre de 2016

ABSTRACT

This article aims to analyze the main elements of the current process of economic globalization as trade liberalization and the flow of foreign direct investment and capital mobility. The consequences of these elements demand a series of criticisms and proposals on how local governments must address globalization and what should be the role of international institutions as an instrument that contributes to integration, particularly of the least developed nations, in the world economy. The purpose of this study is to empirically determine the positive and negative effects of economic globalization on national societies, in order to create better public policies that allow an alternative to global governance and a rapid adaptation to global integration.

Keywords: Economic impacts of globalization, International Investment, Multinational firms, Trade.

RESUMEN

Este artículo pretende analizar los elementos principales del proceso actual de globalización económica como lo son la liberalización del comercio y el flujo de inversión extranjera directa y la movilidad de capital. Las consecuencias de estos elementos exigen una serie de críticas y propuestas relacionadas con la forma en la que los gobiernos locales deben enfrentar la globalización y cuál debería ser el papel de las instituciones internacionales como instrumentos que contribuyan a la integración a la economía mundial, sobre todo en el caso de los países menos desarrollados. El propósito de este estudio es determinar empíricamente los efectos positivos y negativos de la globalización económica en las sociedades nacionales, para poder generar mejores políticas públicas que permitan una alternativa a la gobernabilidad global y una rápida adaptación a la integración global.

Palabras clave: Impactos económicos de la globalización, inversión internacional, firmas multinacionales, comercio.

RESUMO

Este artigo pretende analisar os elementos principais do processo atual da globalização econômica como são a liberalização do comércio e o fluxo de inversão estrangeira direta e o movimento do capital. As consequências de estes elementos, exigem uma série de críticas e propostas relacionadas com a forma na qual os governos locais devem enfrentar a globalização e qual deveria ser o papel das instituições internacionais como instrumentos que proporcione na integração à economia mundial sobre tudo no caso dos países menos desenvolvidos. O propósito deste estudo é determinar empiricamente os efeitos positivos e negativos da globalização econômica nas sociedades nacionais para poder gerar políticas públicas melhores que permitam uma alternativa à governabilidade global e uma rápida adaptação à integração global.

Palavras-chave: Impactos econômicos da globalização, inversão internacional, assinaturas multinacionais, comércio.

Introduction

The phenomenon of economic globalization is not a new event. Between the years 1870 and 1914,a similar process developed which experts of international economic relations have called the first globalization. It was characterized by the increase in the exchange of goods, services, and factors of production, as well as an increase in the transfer of technology, giving rise to the diffusion of economic growth and tighter integration of national economies, whose result was the convergence of global prices and wages (Lascurain and Villafuerte, 2016). The nineteenthcentury globalization encouraged the development of capitalism in all its expression, which later would fade with the beginning of World War II. From the second half of 20th century on, especially in the last two decades, it would be stimulated through an institutional framework based on market economies and rich countries.1 The institutional innovations2 that would follow the majority of developed countries and some Southeast Asian countries would be towards the advantage of the benefits of market economy. These innovations resulted in an increased efficiency and legitimacy of markets; therefore, better and capable governments would be required to create policies to get the most benefit from economic globalization3.

However, it has been proven that, as economic globalization progresses, it brings challenges and opportunities that change the global scenario, being developing countries those who find more difficulties of adaptation. In accordance with the classical theory, the expansion of the global economy entails prosperity through work division and specialization according to comparative advantage in each country. This principle motivates the international transactions, where the less developed countries can take advantage of the global market to get access to cheaper capital goods and technology. On the other hand, the challenges presented by globalization show a diminution in the ability of governments to establish regulatory and redistributive policies that limit social wellness. This situation got worse in most developing countries which do not have strong and efficient institutions capable to manage globalization as demonstrated by the financial crises of the nineties. Likewise, as it has been observed since 2008, developed countries also experience problems due to malfunction of international financial markets causing the subprime crisis, situation that has put the European Union in check, particularly Greece and Spain.

As a consequence to these effects, a series of criticisms and proposals arises concerning how governments must tackle with globalization and the role of international institutions as instruments to assist developing countries to integrate into the global economy. Within the anti-globalization movements, they point out that this phenomenon increases income inequalities worldwide and into the same countries, suggesting that it is necessary to stop it and implement another development strategy. Moreover, some consider that it is only through a higher integration into the international economy that developing countries could benefit.

This debate remains open because most of the arguments for and against globalization are equally valid. However, there are significant countries and people who remain outside of this elitist process in which mainly participate the members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and some emerging economies in Southeast Asia and Latin America. Therefore, it is elementary to consider, if not all, at least much of the elements of economic globalization in order to identify the way to take advantage of the potential benefits of the process.

The purpose of this article is to identify the main challenges and opportunities presented by the phenomenon of economic globalization to countries. For this, the article is structured as follows. First, two basic elements of economic globalization are identified: the open trade and the flows of foreign direct investment and portfolio. Each of these elements will be analyzed and their effects on national economies identified. Finally, the conclusions formulate suggestions for better alternative of global governance and the insertion of developing countries into globalization.

Components and effects of economic globalization

The steady increase in economic interdependence among countries, which has intensified since the early nineties, has brought certain benefits and in some cases obstacles to countries immersed in this process, causing a great debate about the effects of globalization in the economic growth of the countries. Although in social science it is difficult to establish the grade of causality between variables, most advocates, mainly economists (Eichengreen, 1996; De la Dehesa, 2004; Bhagwati, 2004; Wolf, 2005), consider that economic globalization has positive effects on the growth and convergence of the countries because it is a factor for poverty reduction and can serve as a promoter for democratic principles (Sala-i-Martin, 2006). On the other hand, critics (Amin, 1997, Murshed, 2003; Stiglitz, 2002 and 2006; Bhalla, 1998; Hirst and Thompson, 1996; Dunning and Narula, 1997; Wade, 2002), affirm that economic globalization has debilitated the national sovereignty, as well as generated inequalities among countries creating winners and losers. The losers are usually in developing countries and in the lower classes of developed countries, while the winners remain in developed countries and some emerging economies.

On the real plane, the criticisms to globalization have been strong in Latin America; this is linked to the presence of leftist leaders in countries that have turned their backs on Orthodoxy. For example Venezuela, first with Hugo Chavez and today with Nicolás Maduro, is the most notable case. However, it has not been the only one. Others equally critical to global economic integration and the Washington Consensus are Evo Morales from Bolivia, Rafael Correa from Ecuador, Ollanta Moisés Humala Tasso from Peru, and Daniel Ortega from Nicaragua. These leaders are trying to combat the loss of national sovereignty by creating alternative development programs to prevail on the continent.

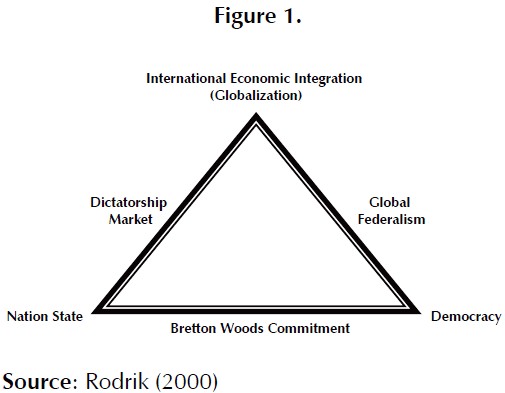

In this debate about the loss of autonomy and sovereignty of nation states, Rodrik (2000) develops a model called the Global Economy Trilemma4 that allows visualizing margins for maneuver of countries in a globalized world (Figure 1). According to this trilemma, countries can only have two out of the three options available: international economic integration, democracy, and the nation state.

International Economic Integration refers to a higher grade of exposure to globalization; that is to say, a situation in which the free circulation of production factors and technology is complete. Nation-State makes reference to territorial jurisdictions with independent powers to make and administer the law without outside influences. Democracy in this context refers to a system of political organization where the right to vote is not restricted, there is a high degree of social mobilization, and political institutions respond to the demands of citizens.

The Trilemma of the Global Economy holds that if countries opt for International Economic Integration (globalization), it is not possible to maintain simultaneously Democracy and the Nation-State; it is necessary to choose one of the two. If Democracy and Globalization are selected (represented in Figure 1 as Global Federalism), democratic supranational organizations will have the power to dictate laws that comply with the standards of such organisms. This would be a model of global governance adapted by supranational organizations. This system has been tried to be implemented in the European Union (EU) where the democratic essence persists in the member states, as they represent the interests of their citizens to the EU institutions. However, this system presents deficiencies mainly in the field of political integration. Evidence of this was the rejection of some member countries to the European Constitution. In addition, if we consider that the distribution of power in the international system is clearly unequal and favors developed countries, there is a serious risk that Global Federalism becomes, in fact, a Global Dictatorship. If the most favored economic groups utilize supranational bodies to implement their agendas through their national representatives, it would promote both economic and political dictatorship in the world.

A second option is to maintain the nation state, making it responsive to the needs of the international economy (called Dictatorship Market).6 This would be a state that pursues global economic integration at the expense of a loss in the decision capacity of its citizens, that is, a loss of democracy in the economy. This is what many antiglobalization movements denounce and other academics and political commentators have baptized as "The Retreat of the State" (Strange, 1996), "The Dictatorship of International Financial Markets" (Block, 1996), or "The Golden Straitjacket "(Friedman, 2000).

In spite of the global economy being still far from full economic integration, if it is complete and no convergence occurs in the preferences of citizens, there would be a political space reduction reflected in the isolation of participatory public debate of the organizations responsible for carrying out economic policy (Central Banks, tax authorities etc.). At the same time, they would disappear (or would be privatized) the social security systems while the economic development objectives would be replaced by the need to maintain market confidence (Rodrik 2000: 183).

Some Latin American countries have experienced this Dictatorship Market. According to Rodrik (2000, p. 183), "once set the game rules on the requirements of the global economy, it must restrict the ability of social groups to access and influence national economic decisions." In the case of Mexico, there exists a certain Dictatorship Market, that can be seen reflected in the different stages of unilateral and multilateral trade and financial liberalization that the country experienced where the state of wellbeing was relaxed in favor of the international market. Also, during the 1995 crisis, the IMF (International Monetary Fund) restricted the policy space of the Mexican government by suggesting the following of certain macroeconomic guidelines to facilitate the borrowing of the necessary funds to overcome the financial shock.7

Currently, the crisis affecting the European Union especially in Spain and Greece is the result of a Dictatorship Market in the sense that citizens have seen a loss of democracy in connection with European and international economic needs (Molina and Steinberg, 2012). It has been proved that the requirements imposed by globalization inevitably collide with the commitments of domestic policy (social protection, employment, etc.). The Dictatorship Market is not the only alternative. A third option is the abandonment of global integration. However, this scheme would force a commitment as the Keynesian style of Bretton Woods, where democracy is maintained within each nation state and economic integration is done through limited and selective protectionist trade measures. These methods previously favored the growth of the countries of the Triad (Europe, USA and Japan), as well as some Asian countries with heterodox development models that allowed them to reduce their poverty levels and have constant growth rates above 5%. However, all of them nowadays have abandoned this system and take the opportunity of economic globalization to fortify their growth (Rodrik 2000 and 2007; Steinberg, 2007, p. 45).

Ultimately, as established by this trilemma, the advancement of international economic integration becomes a political decision. According to the trilemma, the road towards global governance would be outlined in two vertices. The first recreates the commitment of the embedded liberalism proposed by Ruggie (1982) as the Bretton Woods style, which accepts the continuity of the Nation- State and where international agencies make a strong and stable international financial architecture up, allowing a trade regulatory system such as that established by the World Trade Organization (WTO). In this regard, any regime of international economic governance must be compatible with national preferences, ensuring that the agreements are agreed upon by all members. In this manner, countries will be capable to belong a regional block in their respective continent (Regional Federalism), and then in the long term to reach a Global Federalism.

In the case of the European crisis, given its experience in the construction of a supranational project, it seems that in Europe this pathway could meet the challenges of the Global Economy Trilemma proposed in this work. Only through a more federal, political, and economic Europe, it will be able to integrate the regional economy while preserving democracy.

Undoubtedly, even though in the integration of the global economy politics is a determining factor for its constitution, the economic globalization is determined at least by two factors: Trade Openness and the flow of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) through multinational enterprises (MNEs) and capital movements.

Trade liberalization

The growth of international trade in the last decades has been fostered by technological innovations and decrease of tariff barriers. This tendency started at the end of the Second World War, when the foundations of what would become the International Trade Organization were established (ITO), which finally was not consolidated because the US felt that the basic text contained in the Havana Charter restricted US sovereignty. As a result, it was only accepted the part established in Chapter IV of the founding charter of ITO about trade policy (Steinberg 2007). In this way, GATT arose, which would become the right forum for reduction of barriers to international trade.

After eight rounds of multilateral trade negotiations, being the first in Geneva in 1947 with the participation of 23 countries and the final round in Uruguay (1986-1994) with 123 participating members, exports and imports of goods and services as a percentage of GDP8 have had an average growth rate during the 1960-2015 period of 1.6% and 1.5 %, respectively, while trade as a percentage of GDP9 between member countries has had a constant average growth rate of 1.5% in the same period, up to represent 61% of global GDP in 200810 (Graph 1).

At the regional level, in the same period analyzed, the World Bank (2016) suggests that the annual growth rate of trade as a percentage of GDP in Latin America was 1.2%, the European Union has a rate of 1.5%, the Asia Pacific region 2.0%, while the United States and China as single countries have an average growth rate as a percentage of GDP of 2.0% and 2.8%, respectively.

With the end of the Uruguay Round in 1994, there was one of the most important changes in the governance of international trade when the WTO (World Trade Organization) was created. While the GATT is primarily concerned with trade in goods, the WTO and its agreements are in charge of trade in services (General Agreement on Trade in Services, GATS), intellectual property (Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, TRIPS) and investments (Trade-Related Investment Measures, TRIMS). In this way, the pacts reached in the following rounds of negotiations would be under the legal status of an international treaty, and not as agreements between the parties as in the GATT rounds.

Currently, the WTO is the forum of the Doha Round11 which began in 2001 and remains unfinished.12 During this round one of the most conflictive issues was negotiated, as it is agriculture. Therefore, the agreements were complex, not so much for the weight that the agricultural trade internationally has but because it is the most intervened sector in national economies. As a result, there is not a quick solution to these topics; in addition, in this occasion there were more than thirty new member states in the Uruguay Round, which held talks for eight years and on issues relatively less complicated than agriculture. In assessing the benefits of free trade in national economies, one of the most debated questions by economists and specialists in economic growth is whether trade liberalization is beneficial or not for a country. The theoretical justification for trade liberalization is associated with positive results in the long-term economic growth, allowing greater efforts to allocate national production factors with higher yields. On the other hand, it increases productivity by facilitating business innovation and the response to the rise of competitors in the domestic market. Also, economies of scale can be created when trade expands markets. In addition, through the importation of cheaper capital goods new technologies can be obtained, the facilitation of investment, and the accumulation of capital, elements which condition countries to maintain macroeconomic stability and enjoy economic benefits derived from a healthy financial management (Irwin, 2005, Bhagwati, 2004). Finally, another benefit derived from trade is reflected in the institutions, that is, some emerging countries have seen great contributions to the democratic process following the implementation of free trade policies. For example, in China, after the market reforms, the repressions decreased by the regime, compared to Maoist totalitarianism (Wolf, 2005).

However, there is doubt about the validity of these theoretical justifications, especially in developing countries. For example, developed countries and some emerging markets have grown steadily thanks to the implementation of tariff barriers, which were then reduced gradually, and then have had a sustained growth in their implementation of tariff barriers, differing from the theoretical principles of an immediate opening. Meanwhile, the new endogenous growth theory provides an ambiguous answer about the benefits of trade liberalization. The answer varies depending on whether the forces of comparative advantage are moving economic resources toward activities that generate longterm growth (via externalities in R +D, expand productive variety, improving product quality, etc.), or deviate them from these activities (Rodrik 2007, p. 219).

Currently, there are empirical studies about the effects of trade integration in the growth and development of countries, but the results are not definitive. Some studies that have used time series data from different countries and were analyzed through econometric methods such as the World Bank (2011), Frankel and Romer (1999), Sala-i-Martin (2002 and 2006) and Dollar & Kraay (2001), confirm that countries with higher degree of trade liberalization have had better results in their living standards than in previous periods and have grown faster than those countries in autarky.

While there are numerous studies that examine the effects of trade on development through regressions of the rate of GDP growth per capita, in recent years this hypothesis has been strongly criticized, especially by Rodriguez and Rodrik (2000). The authors indicate that in many of these studies, trade liberalization is measured simply as the proportion representing the country's GDP with respect to the volume of foreign trade. However, it is complicated to form a judgment about the effect of trade liberalization on economic growth.13

Secondly, it is difficult to distinguish the effects of trade liberalization and domestic economic policies, since many countries that liberalize its trade regime simultaneously undertake further internal reforms that result in economic expansion. If these reforms are not taken into consideration, the effect of trade liberalization can be confused with other measures that foster economic growth. Finally, in many of the studies the direction of causality is difficult to be determined, that is to say, if trade affects further growth or whether economies that have recorded high growth rates are also conducting a larger volume of foreign trade (Rodriguez and Rodrik, 2000; Rodrik, 2007; Steinberg, 2005; Dollar and Kraay, 2001a).

Although it is increasingly recognized than trade liberalization has a positive effect on economic growth, many analysts are cautious to determine the potential effects of this economic policy on income distribution (Ezcurra and Rodríguez-Pose, 2013). Some authors, defenders of globalization benefits as Sala-i-Martin (2006), attribute a decline in global inequality to the enormous economic growth that Asian countries had, especially China and India, as well as some countries in Latin America. On the other hand, there is also evidence that reforms favoring free trade have coincided with a rise in income inequality in line with the Stolper-Samuelson theorem. For example, Brohman (1996) affirms that reforms in labor markets and trade (main elements of the package of reforms instituted in Latin America through the Washington Consensus)14 have contributed to inequality in income distribution. Under the Orthodox perspective, it is predicted that free trade would be accompanied by an increase in income; however, "the income inequality seems to be increased in Latin America every time that trade increases or is liberalized" (Berry 1998, p. 91). One possible explanation for this phenomenon is that globalization favors the strongest sectors of an economy.

From this debate it can be concluded that during the current period of globalization, the inequality between countries has decreased over the last two decades; largely, this variable has been favored by the rapid growth of what has been called BRICS, especially China and India.15 However, different studies (Bhalla, 2002; Dollar and Kraay, 2001a) and empirical literature reviews (Wolf, 2005) indicate that inequality has increased within each country, although in many cases, the changes in income distribution are due to factors not directly related to the evolution of international trade (Majeed, 2016). Therefore, caution must be implemented at the moment of affirm that trade liberalization is causality of inequality.

For best benefits of trade liberalization, it should be accompanied by a policy mix capable of routing a country to the path of economic growth (Rodriguez and Rodrik, 2000; Winters et al, 2004). Authors like Bhagwati (2004) and Ritzer (2011) argue that economic globalization brings along potential benefits, but also inconveniences to the nation-state, which faces a new forms of government and where it manages its problems with glocal policies (global and local) with the help of international institutions with the purpose to reduce uncertainty global insertion,16 situation which is read as loss of national sovereignty for national governments.

In conclusion, there is no direct correlation between trade openness and economic growth that can be a factor to reduce global inequalities, although not inequalities within each country. Also, trade liberalization does not lead to economic success; it is the policy mix that allows taking advantage of globalization (Gurgul and Lach, 2014). However, just as it is predicted by our Trilemma of the Global Economy, although states pursue a great international economic integration, globalization will then limit sovereignty, and therefore the scope of democratic control. However, the lessons learned from the current global crisis demonstrates that greater international coordination is needed to move towards a Global Federalism in order to continue with dismantling trade in a democratic form.

Interdependence means that the actions taken by a Nation-State have consequences that will be affected by the reaction of other Nation-States and international actors. These actors, as can be Multinational Enterprises (MNE) and their financial flows,17 are an essential part of economic globalization and increasingly participate more actively in international politics influencing decision-making at the international and national level.

Foreign Direct Investment and Capital Mobility

The development of globalization would not be possible without trade opening, technological innovations, and the liberalization of foreign direct investment inflows. As a result of these advances, MNEs have constituted important agents in the expansion of international economic integration because they contribute to alter trade patterns from an inter-industry trade to an intra-industry one, as well as imposing their power in the international political system.

The main benefits of FDI occur through the transfer of technology, especially new varieties of capital inputs that promote competition in the domestic input market (Klein, 2015). Those that receive FDI usually get training for their employees and contribute to the development of human capital. Likewise, the profits produced by FDI also increase the tax income earned in the country (Sanna-Randaccio and Veugelers, 2003; Barrios et al, 2003; Feldstein, 2000; Gilpin 2001). Their presence and effects on national economies are the starting point for criticism, such as MNEs impoverishing the host country and exploiting the national workers. Another aspect criticized of MNEs is that they are more powerful than small countries and harm national sovereignty (Anderson and Cavanagh, 2000). Before addressing these discrepancies, is necessary to know the modus operandi of the MNE and its evolution in recent years.

First, a MNE can be defined as a "company of a particular nationality which owns, in whole or in part, subsidiaries within a national economy" (Gilpin 2001, p. 278). From this definition two elements can be identified: a) the control of a business activity abroad and b) the existence at least of two countries, which can be identified as the country of origin (home state), which is the one the company belongs to, and the host country (host state); that is the one in which the company owns property or has subsidiaries. Companies invest in services, manufacture, or extraction and exploitation of natural resources and these actions can be performed with existing infrastructures or creating new ones through investment, known as "Greenfield" (Gilpin, 2001; Dunning and Narula, 1997). But, why to produce in several countries instead of only in one? And, why is the production in different locations being made through the same company and not by separate companies? The form of expansion of MNEs is given through FDI flows that respond to microeconomic and macroeconomic stimulus.18

The movement of this kind of investment can be interpreted through the eclectic paradigm OLI (Dunning, 1999) which is understood that at any point of time, property and activity patterns of MNEs depend on: (i) the configuration of its competitive advantages (ownership (O) specific) vis-à-vis non multinational companies; (ii) the attraction of competitiveness of a country or region (location (L) specific) vis-à-vis other countries; and (iii) the benefits of companies to exploit these two advantages internalizing the market for advantages of specific O, resulting in the advantage of internalizing (I) (Dunning 1999).

Thus, depending on the advantages that arise in the OLI paradigm, MNEs will decide where to invest to get the maximum benefits. These investment movements are possible due to the rapid development of information and communication technologies (ICTs) and lower transportation and transaction costs, but, above all, by the liberalization of national regulations on foreign investment.

As mentioned previously, since the WTO began its activities the TRIMS agreement was created, related with investment regulation. However, since its start up to day, it is still in contrast to the views that suggest an extension of the agreement.19 Nevertheless, there is empirical evidence that countries prefer to be liberalized without any international rules and that greater protection through investment rules does not guarantee increased flow of FDI, as affirm those who promote such expansion. According to UNCTAD (2015) between 2000 and 2014 more than 1500 regulatory changes in national legislation about FDI around the world were carried out, with only 16% of these having less favorable changes for FDI while the rest guessed a higher liberalization. These results were achieved without the need of a regulatory agreement that limits the host state and allows MNEs to get greater access to different markets and to be actively involved in these.

As a consequence of this deregulation of national rules,20 global FDI flows have increased regularly until the year 2000. Subsequently, it had a sudden growth presenting a historic high in 2007 of $ 3,028 billion dollars (World Bank, 2016) (Graph 2).

The sharp fall of near 22% from 2000 to 2003 was caused mainly by the slow economic growth in most of the countries. As well, it influenced the fall of stock prices, the lower corporate benefits, the slower pace of corporate restructuring in some sectors, and the conclusion of privatization in some countries. Since 2003, the growth of global FDI flow would cause the recovery of previous indicators, being the developed countries the ones which received more FDI, followed by the South, East and Southeast Asia and Oceania, Latin America, and in last position the least developed countries in Africa. The fall of FDI presented in 2007 was mainly due to financial problems caused by the global crisis in 2008. As can be shown in graph 2, global FDI inflows declined in 2014 by 16 %, mostly because of the fragility of the global economy, policy uncertainty for investors, and elevated geopolitical risks.

The decrease of restrictions to investment in most of the countries and the evolution of FDI in the recent decade indicate that there is an incentive to attract it towards national economies. Therefore, what does FDI contribute to the host state? There is a great debate about the possible effects of MNEs in the host country and even more if it is in a process of development. The cost-benefit analysis of this relationship is often complicated and subjective, and is easily subjected to value judgments (Duran, 2001). However, there is a wide literature (Sanna-Randaccio and Veurgelers, 2003; Barrios et al, 2003; Feldstein, 2000; Gilpin 2001; Bhagwati, 2004; Wolf, 2005; Sala-i-Martin, 2006) suggesting that an inflow of investment from MNEs can stimulate local development through increased and improved resources and capabilities (stock of capital, technology, entrepreneurial capacity, access to markets); increased competition, better allocation of resources, human resource development, employment generation, etc. In this regard, companies will wish to move their resources such as capital and technology towards abroad when potential yield is high, especially in markets where these resources are scarce. Certainly, the mere existence of resources in a country does not guarantee that these will contribute to production; however, MNEs allow the use of those inactive resources. For example, oil production requires not only the presence of oil deposits, but also the knowledge of how to find them, the equipment to extract it, and facilities for processing it. To simply extract petroleum is a waste if there are no markets or transport facilities which can provide a foreign investor. The FDI that the MNEs generate can start the improvement of resources to educate the local staff to use the new equipment, the production methods and, especially, to use new technologies. The transfer of innovative methods of work increases productivity, which increases the time available for other activities. Furthermore, the additional competition may boost the current companies to improve their efficiency, what ultimately these elements translate into economic growth (Iamsiraroj and Ulubaşoğlu, 2015).

However, one of the most extended criticisms against MNEs is that these exploit workers in developing countries. According with Bhagwati (2004: 259), "companies [multinationals] that generate work should be applauded, no matter what their motivation to invest abroad is to get benefits, and do not make the common good." The critics do not coincide with this idea based on their arguments according to which MNEs pay lower wages in developing countries. However, there is empirical and econometric evidence which proves the opposite (Brown et al, 2002; Graham, 2000). The studies highlight that the salary paid by MNCs in developing countries is higher than the national average wage. Therefore, what they do is to pay a competitive wage, according to local conditions in each country. Although with some degree of caution, the arrival of FDI should be considered, especially in those least developed countries, as an opportunity to development and not as a threat.

A recurring criticism is that MNEs have become more powerful than national governments. It is said that the largest MNCs in the world have bigger budgets than some developing countries. Although cautiously, it is possible to identify some studies which present a completely different view to this criticism. First, in the political arena, MNEs cannot compare with the capacity of coercion that the government has over its citizens; in this regard, the government continues to have the central role (Held, 2010). Therefore, if MNEs are established under a jurisdiction, these will have to develop under the competent laws, which ultimately are dictated by the national government.21 Second. The way that critics establish that MNEs are more economically powerful than some countries is by comparing the sales of companies to the GDP of the countries, and these are not comparable variables, since they do not measure the same. As a result from this criticism, Grauwe and Camerman (2002) made a comparative study about the added value of companies and the result refutes criticism. The authors conclude that "companies are surprisingly smaller compared with other nation-states" (Grauwe and Camerman, 2002: 15). Therefore, nation-states are the most important agents vis- à -vis MNEs.

However, not everything is positive about multinationals; there are ambiguous points on their activities with harmful consequences: damage to the environment, selling harmful products, and the bribery and corruption that sometimes surround these companies. On the other hand, the lobbies of MNEs were very important to defend their interests in the WTO allowing that institution to apply sanctions to countries that infringe royalty payments for patents (Bhagwati, 2004: 276).

Problems like these should beapproached unilaterally and multilaterally because their consequences affect millions of people in the poorest countries. One of these actions has to start within the own national governments, sanctioning their own laws on institutions that allow this kind of abuse. Multilaterally, WTO should implement clearer and fairer international rules about the activities of the MNEs. Some other actions have already been put in operation as the Corrupt Practices Act Abroad, which is supported by a large number of US companies, or the efforts of innumerable national and international civil organizations; thanks to technological advances, they denounce the various abuses of MNEs around the world and make it possible to know the different abuses of MNEs globally.22

Definitely, MNEs can have positive effects in the host countries since they are capable of generating jobs and in many cases to contribute to the economic growth of such countries or regions where they are installed. Most of the criticism about FDI does not make sense when analyzed thoroughly, although the distribution of possible benefits from MNEs in the host country can be asymmetric and, therefore, controversial. In this sense, the abuses of MNEs cannot be ignored. Here, civil society and national and international laws will play an important role to sanction and regulate these actions.

Regarding to portfolio investment flows, as well as FDI, they have experienced a significant increase in recent decades. The increasing integration of international finances is the result of two aspects: the initiative of the governments to liberalize accounts of capitals and the advances in ICT (Information and Communication Technology) has allowed the immediate diffusion of information globally. It is in part to these capital flows that globalization is manifested in all its expression. However, the benefits of portfolio investment flows are not as clear as FDI.

Theoretical models have identified series of potential direct and indirect channels by which financial integration can promote economic growth. The direct channels are associated with increase in savings, a reduction of capital cost through a better global assignment of risk and the stimulation of development of the domestic financial sector (Feldstein, 2000). Indirect channels are associated to improved economic policies and support for foreign investment to more strongly flow towards the domestic market (Prasad et al, 2003). However, it has not been empirically identified a direct relation between financial liberalization and sustained growth, particularly in developing countries; on the contrary, it is associated with a further increase of macroeconomic instability (Stallings and Studart, 2006, Prasad et al, 2003; OCDE, 2013; Tamarauntari and Diseye, 2013; Yahya et al 2015).

One of the main features of this kind of investment is its volatility,23 which in most cases responds to speculative stimuli24 that have led to different financial turmoil during the nineties, with strong implications to the international financial system, especially in emerging markets. The first crisis of the recent globalization was in Mexico, followed by Russia, the Asian Southeast, and Argentina.25 However, Dobson and Hufbauer (2001) point out that not everything was due to capital movements and the international system, but there was a malfunction of domestic financial markets. While it is true that governments of developing countries must create stronger and efficient national institutions, such as those in developed countries, they should also be responsible for receiving appropriate advice on the implementation of the policies of the Washington Consensus.

The experience of Mexico and other financial crises shows that the opening of the capital account must be conducted with caution, and discipline, and to be regulated and supervised in order to avoid future crisis. There are also proposals to prevent a massive outflow of capital as the "Tobin tax" (Tobin, 1978) which consists of a tax in each financial transaction across national borders. However, the opinions are divided between those who believe the tax would improve the economy of the countries affected by financial speculation, while others consider that would limit the flow of investment and would be politically impossible.26 However, a reform of the international financial system is also necessary, involving the IMF and the World Bank, in order to optimize the governance of the international financial system and facilitate developing countries a secure and better integration into the international capital market.

Nowadays, not only developing countries are concerned about the control of capital movements; developed countries also seek more transparency about the origin of capital as is the case of the Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWF). SWF are investment instruments under public control with large commodity through which exporting countries channel their huge foreign exchange reserves. Usually attend low-risk investments, but increasingly venture into risk capital (Segrelles, 2008). The increase of SWF in sectors (some strategic as ports, banks, etc.) generates great concern in developed countries because they could reach to control them. Some proposals set out clear rules that include aspects such as: base investment decisions on economic factors rather than political ones, transparency in its investment policy, internal control and risk management, fair competition with the private sector, the promotion of international financial stability, and the respect to the rules of the country in which it is invested (Surendranath et al 2010). These rules should be fixed to OECD, IMF, and the World Bank, and even to the WTO (Segrelles 2008, p. 6). At the moment, companies have invested on SWF and have had a positive effect on these, however, little control and lack of information about their origin and finality could cause a future conflict.

Definitely, capital flows either as FDI or portfolio are important for the development of economic globalization. Specially, FDI has positive effects on the host state and developing countries have realized that.27 However, the higher flow of investment is still concentrated in developed countries and emerging economies. This phenomenon can be interpreted through the OLI paradigm in the sense that less developed countries do not have advantages in L, and consequently MNEs prefer to invest in other markets. According to portfolio investment, it also finds better investment opportunities in developed countries and emerging markets. However, the effects that are generated, especially in these last ones, suggests that it is necessary to have reservations about the benefits of mobility of short-term capital, since their speculative volatility makes them unpredictable with great risk to national economies and many of them do not have an efficient domestic financial system capable of managing these movements. Just as in the case of trade opening and under the framework of the Global Economy Trilemma, a higher regulation of financial flows could be better managed through a Global Federalism.

Conclusions

Over the course of this article it has been shown that the components of economic globalization are posing new challenges to governments, especially in developing countries, which have had a more active participation than in the past nineteenth-century globalization.

From that first globalization of the late nineteenth century to the present there are large differences, both qualitative and quantitative but, in spite of great institutional advances and ICT, what stands out in both is that international economic integration is not complete yet. This fact is one of the main responsible causes for the great diversity of national jurisdictions and geographical factors that limit incentives to international transactions that meet the preferences of citizens from different countries.

That is to say, it is under the edge of the Dictatorship Market postulated by Rodrik, which creates more inconveniences for most societies. However, globalization is not in danger; the trend of this phenomenon has been positive but limited. It was identified that while globalization expanses, the cost to remain in autarky increases.

Even though different empirical studies are incapable to establish a direct correlation between trade openness and growth, what they have demonstrated is that free trade is an alternative that produces better net results for those countries that implement this type of trade policy, compared with those who remain in autarchy.

The analysis suggests that in order to obtain these favorable results it is important to create a national scenario with efficient institutions, and find the appropriate policy mix that together with trade liberalization obtain advantage and the potential benefits of globalization. It is not sufficient with trade and financial reforms; developing countries need to deepen and make institutional reforms. In this sense, better laws and institutions, and the proper regulation of FDI and portfolio, can obtain the potential benefits of these movements.

Unifying stances towards regional federalism could be a driver of globalization, provided the agreements respect the basic fundamentals of the WTO and global moves towards federalism, which requires efficient supranational institutions which reflect national interests. Hence, with the proper stage and the appropriate policy mix, globalization would involve net beneficial results.

However, to say that globalization is capable of stimulating long-term growth for all countries that are immersed in it would be erroneous because problems arise with inconveniences and heterogeneous results, mainly in economies of developing countries. One of these problems is the loss of a model of economic and social cohesion as the embedded liberalism (Ruggie 1982). Through the Trilemma of the Global Economy it was proven that countries that wish to join economic globalization cannot obtain full sovereignty and democracy. The proposed option is to give democracy a long-term continuity, as long as international organizations equitably and efficiently supply the needs of the nation state.

To make this possible, reform of economic institutions of international governance will also be needed. In this regard, agencies need to redefine its role globally with ecumenically accepted rules for moving forward fairly in the process of economic integration, allowing all countries to enjoy the potential benefits of globalization.

The WTO will be important in the integration of developing countries. To do this, it must be considered a regime in favor of development where poor countries identify their institutional structure and the appropriate policy mix for a distributive growth to facilitate their integration into the world economy.

As a better governance system of international trade is required, it is also increasingly needed a greater regulation of the international financial system. The past subprime crisis has shown that financial globalization without regulation is less secure. An example of this is the unprecedented effect that the mortgage crisis had in United States, which also had an impact on European, Asian, and Latin American economies.

This speaks of a reality of the interdependence of the states in this globalization process. Since the subprime crisis, which had its beginnings in June 2007 to date, social unrest where citizens are demanding their governments' lack of ability to protect their interests vis a vis the global interests and for having immersed in a vicious circle of unemployment, lack of growth and debt has arisen,.

As was demonstrated along this article, one of the great transformations that most of the countries have experienced in this globalization was a change in their policies towards large economic and financial liberalization. In this regard, we can confirm that according to Rodrik's Trilemma of the Global Economy, which is required for the integration of the global economy, this is a federalized international system, where supranational organisms have democratic practices and facilitate interdependence and global economic development. This step is important toward a global federal system; otherwise the world could fall into deeper economic crisis with wider implications in the societies.

NOTES

1 See Frieden (2006), for an analysis of the principal economic and political events that have shaped to the world economy in the last century. Volver

2 As fiscal policy to stabilize aggregate demand, central banks that regulate credit and liquidity supply, establishing market rules and regulations, among others. Volver

3 The IPCC was established by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) in 1988 to produce studies in climate change and provide assessment to governments. Volver

4 Based on the open economy trilemma (Obstfeld and Taylor, 1998; Obstfeld et al, 2004), under which a country cannot hold at the same time open a capital account, a fixed exchange rate and an independent monetary policy. This contrast of options causes a conflict between the objectives of internal and external stability of each of the countries. Volver

5 See Keohane (2002), for further analysis of global governance. Volver

6 By market dictatorship we refer to a society ruled by the free exchange economy, where a loss of sovereignty of nations is observed in favor of a greater participation in the international markets by signing trade agreements. Volver

7 The economic package received by the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was a great help to cover the obligations of the Mexican government in the short term. Without reaction from the US government to rescue its trade partner, the recovery of the Mexican economy would have taken longer, thus aggravating the social situation. Volver

8 Exports and imports of goods and services represent the value of all goods and other market services received from the rest of the world. They include the value of merchandise, freight, insurance, transport, travel, royalties, license fees, and other services, such as communication, construction, financial, information, business, personal, and government services. They exclude compensation of employees and investment income (formerly called factor services) and transfer payments (World Bank, 2016). Volver

9 Trade is the sum of exports and imports of goods and services measured as a share of gross domestic product. Volver

10 The global GDP average growth rate during the period analyzed was 7.5 % (World Bank, 2016). Volver

11 In Doha other topics such as market access for goods intensive in low skilled-exporting developing countries and high value-added services exported by developed countries are treated. Volver

12 The WTO currently has 162 Member States. Volver

13 Furthermore, it is also possible that the observed relationship between trade volume and growth is due to other factors such as geographical ones. Volver

14 The 10 points posed by Williamson (1990) as fundamental to the Consensus are: fiscal discipline, reordering public expenditure priorities, fiscal reform, and liberalization of interest rates, competitive exchange rates, trade liberalization, financial liberalization, privatization, deregulation, property rights, and the elimination of barriers to foreign direct investment. Volver

15 Group consisting by Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. Volver

16 Wade (2002), argues that agreements created during the Uruguay Round, especially the TRIMS, GATS and TRIPS restrict the autonomy of countries to choose their policy of growth, because they are subject to supranational rules favor of similarly to those national foreign companies. Volver

17 There are other non-state actors such as non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and civil society in general, which have a central role in international politics as economic integration proceeds and diminishes the power of States. Volver

18 These flows also tend to react positively when governments reduce the protection to local companies and when liberalizing FDI inflows (Egger and Winner, 2005). Volver

19 For example, some developed countries argue that the agreement still allows too much freedom of action to the host state (especially to countries in the developing world), and so they press to modify it in order to extend protection to foreign investors and ensure non-discriminatory national treatment to their companies (Steinberg, 2007). Volver

20 The privatization of parastatals has also enabled MNEs to acquire inefficient firms in countries with low levels of competitiveness, but with a potentially attractive domestic market (Gonzalez and Maesso, 2003). Volver

21 However, for very poor countries with extractive industries, MNEs have indeed come to impose conditions to weak governments and / or corrupt (Stiglitz, 2006). Volver

22 See Stiglitz (2006) for proposals to reduce the abuse of MNEs. Volver

23 One of the problems with capital flows in the short term is that this investment cannot be channeled to foster the infrastructure of a country because of their transient nature.Volver

24 The possibility of speculative profits is based on anticipations of movements of financial market variables such as interest rates, types of futures, and derivatives exchange. Volver

25 Capital flight, among other factors, caused the various economic crises that Mexico experienced in 1995, South Korea in 1997, and Argentina in 2001. Volver

26 See Frankel (1996), Jetin B. and De Brunhoff (2000), and Kang and Juanyi (2009) for an analysis of the benefits or inconveniences of the Tobin tax. Volver

27 For example, in the case of Brazil, former president Fernando Henrique Cardoso (creator of the Theory of Dependency), made during his term (1995-2002) a major effort to attract FDI from USA. In Mexico, since the mid-eighties, the different presidents in turn noted that a very centralist and nationalist posture resulted in a decrease in FDI and with it an obstacle to development. For this reason, restriction policies to FDI were declining in recent years in most developing countries. Perhaps more important is the fact that those countries that are outside the global networks of MNEs will be at a considerable disadvantage, mainly because of international trade consists of intra-firm transfers between a subsidiary and another. Volver

References

1. Amin, S. (1997), Capitalism in the Age of Globalization: The management of contemporary Society, Zed Books, London. [ Links ]

2. Anderson S. y Cavanagh, J. (2000), Top 200, The Rise of Corporate Global Power, Institute for Policy Studies, December. [ Links ]

3. Barrios, S. et al (2003), "Foreign Direct Investment, Competition and Industrial Development in the Host Country", European Economic Review, No. 49, pp. 1761-1784. [ Links ]

4. Berry, A. (1998), "The Impact of Globalization and the Information in Latin America" en Bhalla, A. S. (ed.) Globalization, Growth and Marginalization, London: Macmillan Press. [ Links ]

5. Bhagwati, J. (2004), In Defence of Globalization, Oxford University Press, EE.UU. [ Links ]

6. Bhalla, A. S. (1998), Globalization, Growth and Marginalization, Macmillan Press, London. [ Links ]

7. Bhalla, S. (2002), Imagine There's no Country: Poverty, Inequality, and Growth in the Ear of Globalization, Institute for International Economics, Washington, D.C. [ Links ]

8. Block, F. (1996). The Vampire State and other Stories. New York, New Press. [ Links ]

9. Brohman, J. (1996), Popular Development, Rethinking the Theory and Practice of Development, Backwell Publishers, UK. [ Links ]

10. Brown et al (2002), "The Effects of Multinational Production on Wages and Working Conditions in Developing Countries", Research Seminar in International Economics, Discussion Paper No. 484, Michigan University. [ Links ]

11. De la Dehesa, G. (2004), Comprender la Globalización, Economía Alianza Editorial, Madrid. [ Links ]

12. Dobson, W. y Hufbauer, G. (2001): World Capital Markets: Challenge to the G-10, Peter Institute for International Economics, http://bookstore.petersoninstitute.org/book-store//328.html, consulted in September 2015. [ Links ]

13. Dollar, D. y Kraay, A. (2001), "Growth is Good for the Poor", Policy Research Working Paper No. 2587, World Bank, Washington D.C., Abril. [ Links ]

14. Dollar, D. y Kraay, A. (2001ª), "Comercio exterior, crecimiento y pobreza", Finanzas y Desarrollo, Revista trimestral del FMI, Vol. 38, No. 3 septiembre. [ Links ]

15. Dunning J. H. y Narula, R. (1997), "Developing Countries Versus Multinationals in a Globalising World: Dangers of Falling Behind", Discussion Papers in International Investment and Multinationals, Series B, Vol. IX (1996/1997), No. 226, University of Reading, Department of Economics. [ Links ]

16. Dunning, J. H. (1999), "Globalization and the Theory of MNE Activity", Discussion Papers in International Investment and Multinationals, Series B, Vol. XI (1998/1999), No. 264, University of Reading, Department of Economics. [ Links ]

17. Durán, J. (2001), Estrategia y Economía de la Empresa Multinacional, Pirámide, Madrid. [ Links ]

18. Egger, P. y Winner, H. (2005), "Evidence on corruption as an incentive for foreign direct investment", European Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 21, pp. 932-952. [ Links ]

19. Eichengreen, B. (1996), La globalización del capital. Historia del Sistema Monetario Internacional, Antonio Bosh Editor, Spain. [ Links ]

20. Ezcurra, R. and Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2013), "Does Economic Globalization affect Regional Inequality? A Cross-country Analysis", World Development, Volume 52, December 2013, p. 92-103. [ Links ]

21. Feldstein, M. (2000), "Aspects of Global Economic Integration: Outlook for the Future", NBER, Working Paper No. 7899. [ Links ]

22. Frankel, J. (1996), "How well do Foreign Exchange Market Function: Might a Tobin Tax Help?" NBER, Working Paper No. 5422. [ Links ]

23. Frankel, J. y Romer, D. (1999), "Does Trade Cause Growth?", American Economic Review, Vol. 89, No. 3, June, pp. 379-399. [ Links ]

24. Friedman, T. (2000), The Lexus and the Olive Tree. Anchor Books, New York. [ Links ]

25. Frieden, J. A. (2006), Global Capitalism: Its Fall and Rise in the Twentieth Century, Norton, USA. [ Links ]

26. Gilpin, R. (2001), Global Political Economy: Understanding the International Economic Order, Princeton University Press, Princeton. [ Links ]

27. González, R. and Maesso, M. (2003), "Los desafíos que plantea el proceso de globalización económica" in Maesso, M. y González, R. (coord.), La Globalización: Oportunidades y Desafíos, España, Universidad de Cáceres. [ Links ]

28. Graham, E. (2000), Fighting the wrong enemy antiglobal activists and multinational enterprises, Institute for International Economics, Washington, D.C. [ Links ]

29. Grauwe, P. y Camerman, F. (2002): How Big are the Big Multinationals Companies?, Louvain University and Belgium Senate, http://www.econ.kuleuven.be/ew/academic/intecon/degrauwe/pdg-papers/recently_published_articles/how%20big%20are%20the%20big%20multinational%20companies.pdf, Consulted in October 2015. [ Links ]

30. Gurgul, H. and Lach, L. (2014), "Globalization and economic growth: Evidence from two decades of transition in CEE", Economic Modelling, Volume 36, January 2014, p. 99-107. [ Links ]

31. Held, D. (2010), Cosmopolitanism: Ideal and Realities and Deficits, Polity Press, UK. [ Links ]

32. Hirts, P. y Thompson, G. (1996), Globalization in Question, 2nd Edition, Polity Press, Cambridge UK. [ Links ]

33. Iamsiraroj, S. and Ulubasoglu, M. (2015), "Foreign direct investment and economic growth: A real relationship or wishful thinking?", Economic Modelling, Volume 51, December 2015, p. 200-213. [ Links ]

34. Irwin, D. (2005), Free Trade under Fire, Princeton University Press, USA. [ Links ]

35. Jetin, B. y De Brunhoff, S. (2000), "The Tobin Tax and the Regulation of Capital Movements", in Walden, B. et al (ed.) Global Finance: new thinking on regulating speculative capital markets, London: Zed Books. [ Links ]

36. Kang, S. and Juanyi, X. (2009), "Entry Cost, the Tobin Tax, and Noise Trading in the Foreign Exchange Market", The Canadian Journal of Economics, Vol. 42, No. 4, pp. 1501-1526. [ Links ]

37. Keohane, R. (2002), "Global Governance and Democratic Accountability", Duke University, mimeo, http://www.lse.ac.uk/collections/LSEPublicLecturesAndEvents/pdf/20020701t1531t001.pdf, Consulted in October 2015. [ Links ]

38. Klein, M. (2015), "Foreign Direct Investment and Intellectual Property Protection in Developing Countries", Center for Applied Economics and Policy Research (CAEPR) Working Paper No. 018- 2015. [ Links ]

39. Lascurain, M. and Villafuerte L.F. (2016), "Primera globalización económica y las raíces de la inequidad social en México", Ensayos de Economía, Vol. 26, Núm. 48, p. 67-90. [ Links ]

40. Majeed, M, (2016) "Economic growth, inequality and trade in developing countries", International Journal of Development Issues, Vol. 15 Iss: 3. [ Links ]

41. Molina, I. y Steinberg, F. (2012), ¿Hacia una gestión más consensuada de la crisis del euro?, ARI, No. 47, Real Instituto Elcano. [ Links ]

42. Murshed, S. M. (2003), Globalization is not always good: an economist's perspective, Institute of Social Studies, The Hague, Netherland. [ Links ]

43. Obstfeld et al (2004), "The Trilemma in History: Trade Off among exchange Rate, Monetary Policies and Capital Mobility", NBER, Working Paper No. 10396. [ Links ]

44. Obstfeld, M. y Taylor, A. (1998), "The Great Depression as Watershed: International Capital Mobility Over the Long Run", in Bordo, M. et al (ed.): The Defining Moment: The Great Depression and the American Economy in the Twentieth Century, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

45. OECD (2013), Multidimensional Review of Myanmar, Vol 1. Initial Assesment. [ Links ]

46. Prasad, E. et al (2003), Effects of Financial Globalization on Developing Countries: Some Empirical Evidence, International Monetary Fund, March. [ Links ]

47. Ritzer, G. (2011), Globalization: The Essentials, Wiley-Blackwell, UK. [ Links ]

48. Rodriguez, F. & Rodrik, D. (2000). Trade Policy and Economic Growth: A Skeptics Guide to the Cross-National Evidence. NBER Working Paper N° 7081. [ Links ]

49. Rodrik, D. (2000), "How far will international economic integration go?", Journal of Economic Perspective, Vol. 14, No. 1, winter, pp. 177-186. [ Links ]

50. Rodrik, D. (2007), One Economics Many Recipes, Globalization, Institutions and Economic Growth, Princeton University Press, USA. [ Links ]

51. Ruggie, J. (1982), "International regimes, transactions, and change: Embedded Liberalism in post-war economic order", International Organization, 36, No. 2, spring, pp. 379-415. [ Links ]

52. Sala-i-Martin, X. (2002), "The Distributing rise of global income inequality", NBER, Working Paper No. 8904. [ Links ]

53. Sala-i-Martin, X. (2006), Globalización y reducción de la pobreza, FAES, Spain. [ Links ]

54. Sanna-Randaccio y Veurgeles, R. (2003). "Global Innovation strategies of MNE's: implications for host economies", in Cantwell, J. y Molero, J. (ed.), Multinational Enterprises, Innovative Strategies and Systems of Innovation, New Horizons in International Business, Cheltenham, UK. [ Links ]

55. Segrelles, J. (2008), "Fondos Soberanos y sector energético: ¿problema o solución?", Real Instituto Elcano, ARI No. 32/2008. [ Links ]

56. Stallings, B. y Studart, R. (2006), Financiamiento para el desarrollo: América Latina desde una perspectiva comparada, Libros de la CEPAL No. 90, Santiago de Chile. [ Links ]

57. Starnge, S. (1996), The Retreat of the State: The Diffusion of Power in the World Economy, Cambridge University Press, Nueva York, USA. [ Links ]

58. Steinberg, F. (2005), "Cooperación y Conflicto en el Sistema Comercial Multilateral: La Organización Mundial de Comercio como Institución de Gobernanza Económica Global", Tesis Doctoral presentada en el Departamento de Análisis Económico: Teoría Económica e Historia Económica de la Facultada de Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, España. [ Links ]

59. Steinberg, F. (2007), Cooperación y Conflicto Cooperación Internacional en la era de la Globalización, Ediciones Akal, Madrid. [ Links ]

60. Stiglitz, J. (2002), El Malestar de la Globalización, Editorial Taurus, Madrid. [ Links ]

61. Stiglitz, J. (2006), Cómo hacer que funcione la globalización, Taurus, Madrid. [ Links ]

62. Surendranath, R. et al (2010), "The Role of Sovereign Wealth Funds in Global Financial Intermediation", Thunderbird International Business Review, Vol. 52, No. 6, pp. 589- 604. [ Links ]

63. Tamarauntari, M.K. and Diseye, B.T (2013), "Macroeconomic Uncertainty and Foreign Portfolio Investment: Evidence from Nigeria", IISTE, Vol. 3, No. 12 pp. 229-236. [ Links ]

64. Tobin, J. (1978), "A Proposal for International Monetary Reform", Eastern Economic Journal, Vol. 4, No. 3-4, pp. 153-159. [ Links ]

65. UNCTAD (2015), World Investment Report 2015, Transnational Corporations, Extractive Industries and Development, ONU, Nueva York y Ginebra. [ Links ]

66. Wade, R. H. (2002), "What strategies are viable for developing countries today? The World Trade Organization and the shrinking of development space", Development Studies Institute, London School of Economics and Political Science, UK. [ Links ]

67. Williamson, J. (1990): What Washington Means by Policy Reform, Peterson Institute, http://www.iie.com/publications/papers/paper.cfm-research=486, consulted in February 2015. [ Links ]

68. Winters, L. A. et al (2004), "Trade liberalization and poverty: the evidence so far", Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XLII, pp. 72-115. [ Links ]

69. World Bank (2011), Informe sobre el desarrollo mundial 2012. Igualdad de género y desarrollo, The World Bank, Washington, D.C. [ Links ]

70. World Bank (2016), World Bank Data, consulted in September 2016, http://data.worldbank.org/?display=default [ Links ]

71. Wolf, M. (2005), Why Globalization Works, Yale Nota Bene, UK. [ Links ]

72. Yahya, W. et al (2015), Macroeconomic factors and foreign portfolio investment volatility: A case of South Asian countries, Future Business Journal, Vol. 1, Issue 1-2, pp. 65-74. [ Links ]