"You can't fight evil with evil."

ANDRÉS MANUEL LOPEZ OBRADOR

Radical change? From the war on drugs to pacification

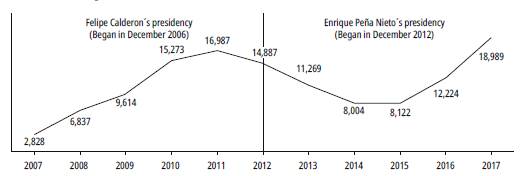

During his election campaign, the new president of Mexico, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO), proposed to grant an amnesty to those involved in drug production and trafficking in order to end the War on drugs initiated by former president, Felipe Calderon (2006-12). Undoubtedly, this initiative is a radical change to the state approach to this armed conflict1, as it involves peace process mechanisms2, such as demobilization, reintegration and transitional justice. The underlying assumption for this measure is that the current strategy to combat drug trafficking, based on coercive measures, seems not to have reduced the high homicide rates associated with this illicit economy reported during the last decade (Figure 1).

Source: Prepared by the authors from Roel, 2018.

Figure 1 Estimated Organized Crime-Related Violence in Mexico (2007-17)

In 2006, Felipe Calderón put the Mexican armed forces and militarized federal police in charge of eradicating organized crime. He promised to quickly restore the state's formal control across the country, deploying many troops to break cartels' territorial dominion of and targeting their bosses with kill-or-capture operations (Crisis Group, 2018).

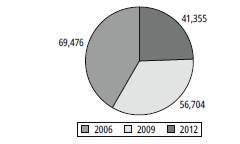

Since then, organized crime in Mexico has transformed. At the end of 2006, at the start of the militarized campaign, six large drug trafficking organizations competed for a handful of coveted drug production and transit territories and were responsible for much of the lethal violence. As the government had murdered or captured many criminal leaders, these six cartels fragmented into dozens of smaller criminal groups (Crisis Group, 2018) and also a varied increase in troops deployed to face cartel factions as can be seen in Figure 2.

Source: Prepared by the authors from Crisis Group, 2018.

Figure 2 Number of Mexican Troops (Soldiers and Marines) Deployed in the War on Drugs (2009-12)

Public security in Mexico has become largely dependent on the army and the navy. Lacking financing, personnel and armament, municipal police forces have shown that they cannot, and sometimes do not want to, face the advance of organized crime. Meanwhile, crime and conflict have deep roots within the state. Corruption, including internal corruption of the armed forces and federal police, supports the collusion of the state with criminals (Crisis Group, 2018).

In this regard, Lessing (2018) promotes the debate about whether it is appropriate to understand violence associated with the war on drugs as an armed conflict. From his point of view, although Mexican cartels do not primarily have political objectives -other than maintaining corrupt authorities on their side-, there are several private armies operating in the national territory to be demobilized, on which the drug market is based and which exercise violence to the extent that state action is repressive. Thus, criminal organizations, in order to protect themselves from the state, counterattack with similar military resources to those used by the government, what the author calls cartel-state war.

Under this scheme, the main reason for the emergence and development of such conflicts is that the state response has had a negative impact on the dynamics of criminal violence. The state's involvement in illicit markets and pursuit of armed factions has been identified as a disturbing factor, creating favorable conditions for increased violence (Cruz, 2016). It is argued that there is a correlation between arrests and dejection of kingpins and an increase in violence (Guerrero, 2018), between military intervention and increased violence (Espinosa & Rubin, 2015), and between the arrest of ringleaders and rising crime rates (Felbab-Brown & Calderón, 2012).

This vicious circle intertwines with three factors: lack of state capability because institutions are repression-oriented; corrupt officials who frustrate government efforts; and a shortsighted vision that affects decision-making; for example, repeated outbreaks of violence that incentivize the use of repressive policies. On the latter, the World Bank (2018) says institutional weakness is a common factor that explains the cycles of violence.

So, without deterrence, there is little chance that drug-related killings stop (Boer & Bosetti, 2015). It should not be forgotten that all countries have manifestations of organized crime; the degree of infiltration of state institutions obviously varies, but the difference is in how authorities respond to it (Eisner, 2015).

Furthermore, it is worth remembering that Mexico has witnessed fragmentation patterns, diversification and criminal migration combined to (re)produce extreme violence. Criminal organizations are not only involved in wars against competitors and officials, but also in internal conflicts while rival factions try to gain control over illicit markets (Garzon, 2016); i.e., the characteristics and dynamics of violence are also strongly associated with the existence of multiple criminal economies. In fact, the size of an illicit economy may directly affect the level of confrontations and disputes among competitors.

No easy way out: The risks of granting an amnesty to drug cartels

Closely related to the previous section, it should be noted that the widespread impact of drug-related violence in Mexico, coupled with the ineffective policies implemented so far to mitigate it, has caused intense debate in media and academia about how useful some classic tools of peace processes, such as the amnesty proposed by AMLO, might be to contain it. Such a scenario poses a relevant question: What are their main risks?

AMLO'S approach reflects a pragmatic view of the problem; it would necessarily involve an agreement between cartels, on the one hand, and the state's authority, on the other, analogous to supporting transitional justice in post-conflict contexts. Offering drug traffickers some kind of judicial benefit such as an amnesty (an agreement on reduced prison terms, or changing the legal framework so as to rule out extradition) presupposes and implies thorough knowledge of their levels of organizational cohesion and legitimacy (Muggah, Carpenter, & McDougal, 2013).

Indeed, this political option represents an opportunity to promote a certain level of commitment from those involved, even though it may not necessarily mean a cease of violence associated with drug trafficking. Following this line of thought, it is worth pointing out that, instead of openly attacking or blocking negotiated pacification processes which is the frame of the amnesty offered by AMLO, drug cartels act as spoilers3 tending to subvert and embed their criminal agendas in the agreements reached4 (Cockayne, Boer, & Bosetti, 2017).

Nevertheless, such measures demonstrate the weakness of the state because they focus on the problem from the logic of drug trafficking organizations, rather than reviewing and strengthening institutional capabilities to fight organized crime. As Villalobos (2012) affirms, proposals that oppose confronting organized crime try to find ways to appease criminals, rather than to strengthen the state to control them. The former seems more comfortable than the latter, since it depends on criminals, while the other needs a high share of political will. In this regard, AMLO'S offer is part of the tendency to use law enforcement strategically, in order to tolerate or simply manage drug-related violence, instead of suppressing it. This shows that he is not interested in monopolizing the use of violence according to Weber's theory5.

A report prepared by the OAS (2015) argue that an amnesty is accepted and encouraged in conventional conflicts, but often finds limits against the criminal violence that prevails in Mexico, a scenario known as other situations of violence under International Humanitarian Law. This is because criminals and insurgents have agendas and motivations of a different nature. Insurgents as non-state armed actors6 are, in principle, official spokespeople susceptible to be amnestied, a treatment resulting inapplicable to organizations involved in criminal activities (Plant & Dudouet, 2015).

We should not lose sight of the fact that criminal groups are motivated primarily by profit, while rebels usually have a political-ideological objective, such as accessing state power or changing the established order. Given this distinction, it is difficult to accept that criminal groups seek political power, except to corrupt it, buy it off, and successfully conduct business (Benitez-Manaut, 2011).

Such an approach is related to the pattern observed by Huntington (1972) 40 years ago: "The criminalization of political violence is more prevalent than the politicization of criminal violence" (p. 13). Following this logic, Phillips (2015) states that there are two particularly relevant kinds of incentives: material incentives and intentional incentives. The material ones are basically financial or other tangible benefits, on which organized crime depends to develop its illicit economies. Intentional incentives are intangible rewards that derive from the sense of satisfaction in having contributed to a good cause or attempting to achieve the greater good, as is the case of rebels (Table 1).

Table 1 Incentives/Insurgency Market vs. Transnational Organized Crime

| Insurgence | Transnational Organized Crime | |

| Incentives for members | Intentional (Intangible) | Material (Tangible) |

| Market | Ideas/Public Opinion | Illicit Economies |

Source: Prepared by the authors from Phillips, 2015.

Likewise, this aspect represents a challenge to conventional tools used in conflict management called path dependency as identified by Whitfield (2013), in which political actors may be partners for peace-building, while criminal actors are a target for the police. Thus, curbing criminal violence becomes more complex than addressing political violence by the nature of the commitment. Generally, granting an amnesty to political actors is linked to a Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR)7 process; however, when it comes to expectations, criminal groups are generally more limited to the reasons described further on.

Sustaining logic

Granting an amnesty to criminal groups requires an understanding of two complementary aspects. First, we need to understand the criminal economy that sustains them, the reasons for participation and challenges in the integration of these actors in the formal economy. This is even more important considering the current trends of criminal violence in Mexico: a rapid transformation and change of leadership, in combination with the resistance of the criminal economy (Gonzalez Bustelo, 2016).

So, it is possible to say that judicial benefits turn out to be inapplicable to criminal organizations as it threatens their fundamental financial interests and would be like a potential plea to their right to bankruptcy. Given that they have no political-ideological motivations, there is no way to dissuade them to disarm through a political agreement and, therefore, to operate within the economic logic. In other words, when it comes to illegal political groups, the assumption that amnesty granting guarantees may achieve disarmament is reasonably certain, but not when it comes to criminal groups, whose ultimate goal is to profit, as in the case of drug trafficking (Zepeda, 2018).

Following this logic, it should be mentioned that specialized literature often tends to ignore the moral implications of violence. Social sciences, such as criminology, economics or political science, emphasize the rational nature of violence and its instrumental value or utility, attributing it certain ends and means. For differentiation purposes, Schedler (2014) proposes four fundamental dimensions of violence morphology: final recipient, degree of organization, motivations and power relations (Table 2). So, when it comes to insurgency, no reference is made to the exercise of a kind of accidental, random, disorganized violence, but a violence that pursues a specific objective of a political nature (Guindo, 2013). Rebels use violence for five reasons: desertion, intimidation, provoking a government response, spoiling negotiations, and as publicity for their cause (Phillips, 2015).

Table 2 Fundamental Dimensions of Violence Morphology

| Dimension | Conceptualization |

|---|---|

| Final Recipient (state agents or citizens) | Non-state armed actors differ in its primary objectives. They can direct their violent acts against state agents or citizens. |

| Degree of Organization (individual or collective) | Violent citizens can act as lonely wolves, belong to sporadic cooperation networks, or build complex and hierarchical organizations. |

| Motivations (political or community) | When violent acts seem to be motivated by general concerns such as public policies, state institutions or structure of the political community, it is political violence. When it seems to be motivated by particular interests such profitability, it is criminal violence. |

| Power Relations (dominance, competition and rebellion) | Individuals may appeal to violence against adversaries weaker than them, operating as a tool of domination. When social groups appeal to violence against other groups of similar level, it operates as an instrument of competition. When less important actors exert violence against members of higher hierarchical level, it is rebellion. |

Source: Prepared by the authors from Schedler, 2014.

Instead, this kind of violence is inconsistent with the objectives pursued by illegal groups such as cartels as this is a tool in itself. It is worth noting that drug trafficking violence causes a high degree of violence for a quite simple reason: it is unlawful. There are no regulating mechanisms to these actions, causing those involved to resort to even further violence. Illegality, combined with weak institutions that poorly fulfill the function of suppressing this business, leads these groups to settle their disputes violently. In sum, criminal groups, without legal recourse, use violence to enforce agreements, but its excessive use is often costly and may result in death or imprisonment of those responsible. Therefore, their goal is different, as they seek to protect or expand illegal activities territorially.

Further challenges

Absence of a political-ideological agenda in criminal organizations represents a different challenge-no obvious possibility of a peace process with an aim to stop violence in exchange for the opportunity of attaining goals by peaceful and democratic means (Plant & Dudouet, 2015). This is an insurmountable problem in contexts where rent-seeking is the force that drives the actions of non-state armed actors, such as cartels. The possibility of renouncing the use of its main tool to establish dominion, resolve disputes and manage their illegal activities is extremely low (Kemp, Shaw, & Boutellis, 2013). While there are lucrative illegal markets, the use of violence is necessary.

In other words, what motivates drug dealers to engage in this activity, using violence as a mechanism, is its high profit margin. And that incentive will not disappear with an amnesty, at least for most of those involved in this activity (Chabat, 2018). The possibility that leaders and members of drug cartels be willing to give up their primary means to manage their plazas8 does not attract much support in Mexico. The prevailing (founded) opinion is that human dignity is the very last of their priorities; therefore, an amnesty would not solve the problem of violence because, even if the amnestied ceased their criminal activities, the economic incentive would continue, and new criminals would take up their role and place.

There may be no real perspective on the effectiveness of an amnesty either without the willingness to transform the calculated rationale of cartels. Van Den Eertwegh (2016) considers that the latter is particularly critical because there is a risk of a zero-sum game; i.e., criminal actors will find it virtually impossible to abandon their illicit economies overnight and the government will have to tolerate crimes during an adjustment phase and assimilate a difficult period for the population. This involves promoting and sustaining the economic transformation necessary to address criminal agendas without losing social support for a peace process; therefore, setting a strategy for criminals' economic needs, able to limit their involvement in illicit markets, requires negotiating a broader set of standards for social legitimacy, legality of certain activities, and use of violence.

Moreover, their sources of legitimacy and the relationships they have with communities often range between conformity and resistance, between cooptation and coercion9. Illicit economies are not only related to organized crime, but to livelihoods of large segments of the population who lack alternatives (Muggah & O'Donnell, 2015); i.e., peace processes, of which the granting of an amnesty is part, have to pay attention to the political economy of violence. Thus, granting an amnesty in situations other than armed conflicts is risky when there is a hybrid political order, in which non-state armed actors, such as cartels, may also perform some public functions at the local level (Santamaria, 2017).

Accordingly, Fiorentini and Peltzman (1977) establish that when a criminal organization has gained a monopoly on coercion in its area, it may perform activities for the state, such as tax collection or the provision of public goods and services; i.e., criminal groups progressively acquire legitimacy as parallel authorities in areas where they operate, supplanting the state in the monopoly on violence.

From this perspective, it should be reminded that a state develops its claim to the monopoly on the legitimate use of violence, i.e., with the ability to exercise authority within its borders to protect its inhabitants. Thus, an element of the social contract that anchors its legitimacy is to prevent the use of coercion by others in their territory. If a state is weak or lacks the capacity to exercise control over an area or geographic location, it will probably be considered illegitimate by citizens, and various non-state actors can fill that power vacuum. As a result, state institutions end up sharing control with these informal institutions (Shaw & Kemp, 2012). The strategic role of criminal actors affects the state's fundamental purpose and has political implications, as they act as competitive state-makers undermining its functionality and legitimacy. So, the greater order and security provided to communities, the greater the possibility of becoming proto-states de facto with a high degree of political capital10, thus reducing their ability to act (Felbab-Brown, 2013a).

Leverage

Actors who do not have any political ideology or noble cause from a social point of view will always perceive this judicial or legal benefit as a chance to obtain preferential treatment and perpetuate confrontation. Indeed, the Mexican government will have to solve difficult issues in the application of prison sentences inferior than those established for crimes committed by approving changes in the legal framework, such as the annulment of extraditions (Bosetti, Cockayne, & Boer, 2016). From this perspective, Hope (2012) asserts that granting an amnesty to cartels, as opposed to insurgent forces such as the currently demobilized Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (farc), is morally and politically complex since it involves giving in to a fundamental principle: law is non-negotiable. This violates the ethics of conviction in the Weber's sense.

This dilemma is illustrated by the controversial truce between La Mara Salvatrucha (MS13) and Barrio 18 in El Salvador during 2012-13, which led to a massive and sustained reduction in homicides. Former president Mauricio Funes (2009-14) initially denied any involvement, even dismissing the impact of the gang truce in the reduction of violence because it meant in essence a tacit acknowledgment of giving in to gangs (Vukovic & Rahman, 2018). In other words, the following message was sent: The state is weak and can be blackmailed. Four years later, current president Sanchez Ceren not only rejected the truce for considering it ethically suspicious and strategically wrong, but subjected gangs to increasingly militarized repression. In fact, a law prohibiting negotiation with them was passed, which even penalizes "calls for dialogue" (Tabory, 2016).

In Mexico, an amnesty would send a negative message about the rule of law and leave serious crimes unpunished that no society can legalize. This measure poses the moral dilemma of not punishing behavior that, besides being illegal, society considers reprehensible, such as murder, torture and kidnapping. Certainly, the discussion is played down when speaking of drug trafficking since, in principle, such illicit activity simply supplies a demand for a product that is theoretically used as a personal choice-falling within the scope of individual freedoms. But if we refer to crimes that, by social consensus, are inadmissible, such as murder or torture, there is much to consider about an amnesty. Indeed, this has been a controversial issue in the peace process that seeks to incorporate FARC into civil life11.

In this regard, the proposal to grant an amnesty has the disadvantage of conferring belligerent and politically unjustified legitimacy to criminal actors, such as the Knights Templar or the Sinaloa Cartel, to the extent that these would potentially be considered official spokesmen to the Mexican government. This means turning them into factual powers, authorizing civil servants in the security and justice sectors to collaborate with them out of fear or money (Salcedo Albaran, 2018). Basically, this condition would be their diplomatic recognition as enemies by the Mexican state (Lessing, 2016), which in turn would allow the main cartels to further increase their influence and power, largely due to the country's entrenched corruption and lack of accountability, as happened in Colombia during the DDR process with the paramilitary in 2000 (Giraldo & Preciado, 2015).

Undoubtedly, social polarization around organized crime and instrumentalization of this issue for electoral purposes has profound consequences on the possibility of an amnesty to reduce violence and crime rates nationwide. In contexts where criminal organizations control significant portions of the territory to the point of challenging their power, governments may be inclined to take such measures as an alternative to onerous repressive strategies, being able to attain electoral revenues from the improvement in public security conditions as a result of the agreement made, as a peace dividend (Zukerman, 2016). However, for supporters of a more repressive approach, an amnesty will be politically difficult to assimilate, especially when the counterparty is a criminal group with no political-ideological ambition. Equally, governments fear a public opinion backlash, negative media coverage of the initiative, and paying a high price in political and electoral gains (Garrigues, 2015).

Instead, setting a decline in levels of violence as the ultimate goal, following the granting of an amnesty in non-military contexts, is a substantial risk, as drug trafficking organizations may perceive that, if they become violent enough, they can sit down and negotiate with the government for more concessions. This violates the ethics of responsibility in the Weber's sense because the precarious peace that would be achieved by AMLO today may cause an upsurge of violence tomorrow; to wit, short-term gains will be canceled by increased violence in the medium term. There are ways to alter the violence perpetrated by criminal groups, and that is precisely what the amnesty aims to achieve: "cartels have the ability not only to wage war but to stop it" (Hagedorn, 2005, p. 154).

In this sense, Farah (2012) argues that, in the case of El Salvador, negotiated peace represented a high political gamble. Imprisoned gang leaders were offered better imprisonment conditions in exchange for stopping executions and extortion. Funes risked worsening public security in the long term. The truce gave maras a share of political power, which improved safety indicators reported for that period. It also reduced gang homicides because territories were divided by mediation with the consent of the state. Thus, gangs could force a collapse at any time simply by threatening to increase the number of homicides. Even, gang leaders were surprised and pleased with the results of negotiations, and began to understand that territorial control and organizational cohesion make it possible to obtain concessions from the state, while maintaining their criminal nature (Ramsey, 2012).

Cruz and Duran Martinez (2016) claim that situations like this can encourage criminal groups to strategically manipulate the visibility of violence12 and, thus, obtain greater concessions from authorities. Hiding violence seems to be a viable strategy because its level of visibility is easier to monitor by authorities as an indicator of compliance with the agreement. In Mexico, cartels may be less likely to show violence when they receive privileges from the state or when they fear its reaction to high-impact attacks. Thus, they may decide to inflict violence in a manner that is not sensed by the government, which means not an actual but an artificial reduction of criminal violence. So, AMLO will depend on criminal actors to monitor the parameters of their covenant when trying to promote conditions for durability.

The feasibility of agreements will basically be contingent upon two fundamental conditions: (i) that the state plays a role as an administrator, and (ii) that participating criminal groups are cohesive and have organizational leadership to facilitate territorial control and strategic reliability for compliance. Regarding the first requirement, a pact involving the state as a whole will probably fail due to police actions and lack of attention to structural factors that lead to violence and may motivate cartel members to reoffend. As to the second condition, the degree of internal cohesion is not only vital to discipline individual and collective behavior of criminal groups during a peace process, but also to overcome the difficulty of identifying partners and authorized representatives within criminal organizations, and thus having the ability to take positions with respect to the state (Cruz & Durán Martinez, 2016). This poses a singular paradox-all criminal peace processes require groups with strong leadership and highly cohesive structures.

Considering the above, it can be argued that AMLO'S approach is directly linked to the discussion initiated by Felbab-Brown (2013b) on how to create good criminals: highly organized, not openly violent, with limited corruption capacity, and no range of service offer to society. In essence, an amnesty is not intended to de-escalate the illicit market, but to model its behavior-low profile, with no open confrontation position, and moderate mortality rates. From this perspective, this approach shows that governments sometimes use law enforcement strategically to object, tolerate or simply manage violence associated with organized crime, rather than to combat it. So, since it seeks to reduce criminal violence only, an amnesty is likely to be a mere damage limitation strategy.

Conclusions

We have seen that a radical change has taken place in the approach of the state to end war on drugs and employ peace keeping mechanisms, as if part of a peace process. We can see this approach in the election campaign in which the candidate AMLO offered the granting of an amnesty, demobilization and use of transitional justice. This shows how the state may move to pragmatic methods to outdo drug-related violence and leave behind the more traditional and tabooed outlook of dealing with it.

In this regard, we can identify AMLO'S approach as a tendency to use law enforcement strategically in order to manage violence. This approach involves agreements between cartels and the state authority, as well as supporting reduced prison terms, amnesty or ruling out extradition and other mechanisms as if in a post conflict context. As a pragmatic approach, it is radical in the way the state approaches eradication of drug trafficking violence, considering that the traditional state method have solely been based on repression; however, this approach looks to reduce criminal violence only, where an amnesty is likely to be a mere damage limitation strategy.

From another perspective, granting an amnesty to criminal groups, as opposed to insurgent forces such as the currently demobilized FARC, is morally and politically complex. It involves giving in to that fundamental principle that law is non-negotiable. Indeed, here the risks are higher than in a military context as drug trafficking organizations may perceive that, by becoming violent enough, they can sit down and negotiate such fundamental principles with the government in order to receive further concessions.

Further, AMLO'S proposal to grant an amnesty has the drawback of conferring unjustified legitimacy to criminal actors, such as the Knights Templar or the Sinaloa Cartel, to the extent that these would potentially be considered official spokesmen in dealing with the Mexican government, turning them into factual powers. This condition would be their diplomatic recognition as enemies by the Mexican state, which in turn would allow the main cartels to further increase their influence and power, largely due to the country's entrenched corruption and the lack of accountability, as was the case of Colombia with the paramilitary during the DDR process.

Finally, the chance that leaders and members of drug cartels would be willing to give up their control and methods of intimidation had not found much support in Mexico. The prevailing founded opinion is that human dignity is the least of their concerns. Moreover, what these criminal organizations use in order to establish their presence and domination and manage their illegal activities in their plazas is precisely in violation of human dignity. Therefore, a pragmatic approach such as the consideration of an amnesty would not solve the problem of violence since the economic incentive would continue, and new criminals would only but substitute them.