Introduction

Latin American integration is at a crossroads. States seem to question current initiatives while still acknowledging regional integration as relevant. Some countries have changed their minds regarding some mechanisms (e.g. of late, almost all states parties to UNASUR have questioned this mechanism and Colombia as well as Ecuador have announced its decision to leave it, and the latter has also distanced itself from ALBA), some others are seeking membership in quite different ones (Ecuador has expressed its interest in becoming a member of the Pacific Alliance), and others have supported a new integration initiative (Chile's PROSUR proposal launched in March 2019). These events suggest a modification regarding their interpretation of what regional integration is and ought to be. These movements mark an important moment for Latin American integration, potentially a breaking point, because these mechanisms are as strong as the number of state parties and their commitment. Thus, the reshuffling taking place signals a reconsideration of the notion of the problem that regional integration poses and, consequently, its solutions. In this context, discussing regional integration seems more pertinent than ever and doing it in terms that highlight its inherent pluralism is not only necessary but urgent.

Regional integration has been studied and described in a variety of ways by the literature. One recent approach has been the argument, made in this forum in the first issue of 2018, suggesting that it is a 'wicked problem' (Garcés, 2018). In brief, the argument suggests that Latin American integration is not only an attempt to solve to a problem, as a policy usually seeks to be, but it is itself a problem, being defined as the mismatch between reality and expectations or, in other words, the discrepancy between what it is and what it ought to be (Garcés, 2018).

The wicked problem argument, based on the planning literature, sought to show that Latin American integration initiatives not only fail to meet original expectations (as stated in their founding treaties) but also follow a decalogue that gave them the honor of bearing that title. The ten considerations, quoted from Garcés (2018, pp. 101-113), can be summarized as follows (for an elaboration the reader is invited to read the full article):

There is no definitive formulation of a wicked problem.

Wicked problems have no stopping rule.

Solutions to wicked problems are not true or false, but good or bad.

There is neither an immediate nor ultimate test of a solution to a wicked problem.

Every solution to a wicked problem is a 'one-shot-operation'; because there is no opportunity to learn by trial-and-error, every attempt counts significantly.

Wicked problems do not have an enumerable (or an exhaustively describable) set of potential solutions, nor is there a well-described set of permissible operations that may be incorporated into the plan.

Every wicked problem is essentially unique.

Every wicked problem can be considered to be a symptom of another problem.

The existence of a discrepancy representing a wicked problem can be explained in numerous ways. The choice of explanation determines the nature of the problem's resolution.

The problem solver has no right to be wrong.

In the aforementioned article, these conditions separate 'tame' problems from 'wicked' ones. In a nutshell, the difference lies on the complexity that the latter entail compared to the former. Whereas tame problems can be precisely defined, allowing for one and only one right definition that can be exactly expressed, also leading them to have one right solution that is exactly expressed as well, wicked problems challenge the very possibility of a unique clear-cut definition and, consequently, reject only one precise and exact solution. Put differently, while tame problems lend themselves to elegant solutions, wicked ones seem to require the opposite, i.e. clumsy ones (Verweij et al., 2006).

Presumably, the difference can be rooted, at least to an extent, in the philosophical tradition with which problems are approached. While tame problems seem to conform to the positivist template and its pursuit of 'the truth' and certainty, wicked problems seem located within the interpretivist framework and its attention to different meanings and interpretations of the same phenomenon (whether problem or solution).

In this sense, this article elaborates on the call for plurality that wicked problems entail with focus on Latin American integration. At the same time, it also recognizes that this plurality in and of itself can be a problem. It turns out to be problematic because from this perspective, at the extreme, there could be as many interpretations as observers of the phenomenon, which would make any attempt to define a problem and provide resolutions virtually unworkable. Hence, Latin American integration could have a virtually indefinite number of meanings. The sheer amount of notions of the problem, solutions, and ways to address it quickly appear daunting enough so as to demotivate such enterprise.

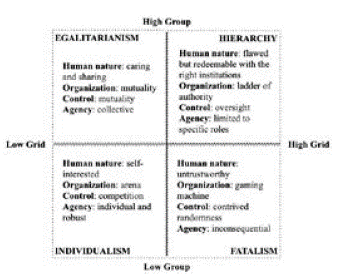

Against this backdrop, the aim of this article is to further the argument in favor of a workable plurality using an analytical tool that can harness its potential while making it tractable in order to address the wicked problem of Latin American integration. The instrument advanced for such undertaking is grid-group cultural theory. This framework focuses on individual freedom of choice and the dimensions that influence it, namely, grid (externally imposed prescriptions) and group (group affiliation effect). These are best understood as a matter of degree. Their combination (as in a coordinate axis) produces four distinct and irreducible worldviews, ways of life or rationalities: individualistic, hierarchical, egalitarian, and fatalistic. Each world-view provides a different understanding of the same phenomenon. In this case, this means four distinct notions of regional integration. In particular, each rationality holds a distinct notion of what the literature regards as essentially contested concepts1, which undergird those ideas about integration.

Importantly, the ways of life that make up this typology are mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive. This means that this framework encompasses all possible rationalities, giving order to the valuable complexity of wicked problems and making it much more plausible to solve them. Consequently, it is accepted that Latin American integration is indeed a wicked problem and it is argued that grid-group cultural theory is a framework to provide clumsy solutions.

In order to elaborate that argument this article is structured in four sections. The first introduces grid-group cultural theory with an emphasis on the notions of human nature, control, organization and agency derived from each rationality or worldview. Building on these ideas, the second section suggests what cooperation, conflict and integration mean for each way of life and employs these insights to study Latin American integration. It does so by placing what are arguably some of the major regional integration initiatives on the coordinate axis made by combining the theory's dimensions. The third section elaborates on the issue of a clumsy solution to the wicked problem of Latin American Integration and discusses what it would entail, in light of the analysis carried out. The last section concludes. Note, therefore, that the aim of this essay is not to provide one additional definition of regional integration with any conclusive aspirations, nor is it to adhere to an established one. Instead, highlighting plurality, the purpose is to make a small contribution to the literature by identifying the definitions that may be associated with each rationality. Finally, note as well that, as in the aforementioned article (i.e. Garcés, 2018), although the argument can be elaborated for each regional integration mechanism, for the purposes of this article, Latin American integration is studied as one phenomenon, as one wicked problem.

Grid-Group Cultural Theory

Grid-group cultural theory (cc) offers a functionalist approach to the study of socio-cultural viability2 (Thompson et al., 1990). It adheres to a rather interpretivist or constructivist philosophy of science. As such, it builds on the assumption that although there is an objective world, we always approach it from a prejudiced perspective. Consequently, that world is always perceived from a vantage point, and the latter is socially constructed. These constitute the worldviews that guide our perception of the world, construct the meaning we have of it, and contribute to our making sense of it (Bell, 1997).

Perhaps its most important concepts are cultural bias and social relations. The first refers simply to shared values and systems of beliefs. The second denotes what can be conceived as the tapestry of interpersonal relations, which make up ways of life. Turning back to the idea of sociocultural viability, cc suggests that the viability of each way of life hinges on the interaction between cultural bias and social arrangement, an interaction that can be mutually reinforcing (Thompson et al., 1990). Put otherwise, those who subscribe to a given way of life sustain it and maintain it by acting and behaving according to the corresponding shared values and beliefs. The latter, in turn, legitimize their social arrangements.

CC cultural theory has been so baptized due to the two dimensions on which it focuses, namely, grid and group. From this perspective individual human freedom is at the locus of attention. Nevertheless, it is approached as embedded within a social context. Thus, the main interest is to study how individual choices are influenced by society. Therefore, according to it, there is a constant interaction between the individual and their context, or the agent and the structure. The variation in this sociality (Thompson et al., 1990) or human organization (Hood, 1998) can be adequately captured by two dimensions: grid and group.

Regarding grid, it denotes external prescriptions. As such, it refers to the extent to which choices made by individuals are restricted by prescriptions external to them. There is a straightforward trade-off in this dynamic. The less the externally imposed prescriptions, the more that the individual's life is up for grabs (Lockhart, 1998; Thompson et al., 1990;). In other words, the deeper and wider the social impositions, the more restrictions on people and, therefore, the less individual freedom of choice.

Apropos of group, it signifies collective affiliation. In this sense, this dimension refers to the degree to which individuals are included within bounded units. This means that an individual's freedom of choice is negatively associated with the extent of membership in a given group. Put simply, the greater the embeddedness of the individual within a group, the more the individual choice is determined by the collective (Lockhart, 1998; Thompson et al., 1990).

Combining these two dimensions produces four distinct and irreducible ways of life. This is a typology of worldviews. Thus, they are mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive (Figure 1). The resulting ways of life, located in each quadrant, are fatalism, hierarchy, egalitarianism, and individualism3 (Thompson et al., 1990).

Source: Douglas in Bell (1997)

Figure 1 Four Rationalities, Worldviews or Ways of Life in grid-Group Cultural Theory.

Ways of life can also be considered as rationalities. This is so because what is deemed 'rational' is determined by each particular way of life (Bell, 1997). This is, of course, consistent with the interpretivist position (Hollis, 1994; Hollis & Smith, 1990). Moreover, these rationalities are interdependent since the survival of one hinges, to a certain extent, on the existence of the others (Thompson et al., 1990).

Interdependence among the four rationalities is particularly relevant because it can provide an account of change. Even though each way of life is viable, following the process mentioned earlier, they are not isolated but permeated and constantly being challenged by new events in the world, the perceptions constructed of them, the values and beliefs inducing the latter and the behaviors they lead to. Therefore, the extent of their existence is subject to change (Thompson et al., 1990). How does change take place? Change is dependent on surprise. Surprise is the "mismatch between expectations and reality" (Garcés, 2015, p. 96). Whenever there is enough evidence of surprise, or whenever a given way of life fails to match reality with original expectations enough times, people are likely to change their preferred way of life to one that bridges the gap between expectation and reality more consistently (Thompson et al., 1990).

Interestingly, the concept of surprise is defined in the same terms as the concept of problem. To be sure, a challenge could be raised as to whether a positive surprise, when reality exceeds expectations, can be considered problematic. For the purposes of this article, even positive surprises are problematic because, good as they may be, they still fail to comply with predictions and aspirations, and the ultimate thing of value here, i.e. the ultimate 'good', is to provide some sense of certainty. Thus, positive as well as negative surprises are problematic. Accordingly, whether surprise and problem can be considered as synonyms per se or not, for the current purposes, the implication is the same, to wit, they cause change.

The implication of the notion of change is that there is zero-sum game among rationalities. Certainly, this is because there is a limited number of people for whose preference they are competing. Thus, the loss of one rationality is the gain of another and change in all directions is possible (Thompson et al., 1990).

Importantly, these four rationalities should be considered as 'ideal types' (Altman & Baruch, 1998; Coyle, 1994;). These are to be understood as 'pure forms' that cannot be found as such in reality, nor do they reflect the 'true content' of history (Kâsler, 1988). In this sense, they are rather heuristic devises created in order to facilitate the grasp of complexity by giving the multiplicity of individual phenomena some order and evaluate whether, and the extent to which, they conform to one or the other. Hence, these can be regarded as four extreme positions in two continua or spectrums, allowing for considerable variation between each antipode.

Consequently, from this perspective, the combination of grid and group dimensions generates four quadrants, each having a distinct notion regarding what can be regarded as essentially contested concepts (Freeden, 1996) and fundamental themes. Due to the fact that regional integration deals with themes such as conflict and cooperation and both are intrinsically related to human nature, in what follows an exploration is carried out concerning the meaning that each rationality gives to human nature. Human nature becomes important in this argument because notions of the human being and their agency establish the foundation about the relationship and dynamics with others, in society. Regional integration is just that, at the international level (Figure 2). Moreover, scrutinizing human nature involves discussing human's preferences regarding social arrangements, and "[preferences are formed from the most basic desire of human beings- how we wish to live with other people and others to live with us" (Thompson et al., 1990, p. 57).

Hierarchical rationality: All about the system

The first rationality is located at high grid and high group. The hierarchical social system is characterized by a relatively wider and deeper external prescription and a relatively stronger group membership. Therefore, the freedom of choice that individuals can enjoy is restricted on both dimensions. On the one hand, their choices are determined by the group to which they are affiliated. On the other, they are also regulated by the self-imposed external prescription, which can be best illustrated by the specialization of roles. Both controls are required since human nature is considered as inherently flawed but at the same time as redeemable if regulated by institutions that can create certainty and, thus, confidence (Thompson, 2003). From this perspective, therefore, laws and regulations are necessary in order to reduce uncertainty in human behavior and the possibility of sub-optimal choices. Those institutions are best illustrated by the creation of specific roles that are assigned to individuals, dictating the breadth and depth of their agency. Those regulations are prescribed by those wielding authority, which are located in the higher ranks. Accordingly, this rationality regards an organization as a 'ladder of authority' (Hood, 1998). Controls serve to manipulate those in lower ranks and maintain the status quo. Should internal conflict emerge, this system has a few instruments to ensure the survival of the system, such as "upgrading, shifting sideways, downgrading, resegregating, redefining" (Douglas, 1982, p. 206). Regardless of the specific strategy, the overall framework to exercise control for hierarchists is oversight (Hood, 1998).

Individualist rationality: All about the agent

The second rationality is located at low grid and low group. Since there is virtually no group affiliation and no externally imposed prescriptions, the individualist social arrangement offers the most freedom of choice, one that is for all intents and purposes unrestricted. As such, should there be any restrictions, they are merely conjunctural and always subject to negotiation (Thompson & Ellis, 1998). From this perspective, humans are "inherently self-seeking and atomistic" (Thompson, 2003). The absence of an authority makes the system anarchical and paves the way to the emergence of self-authority, making this a self-help system. Therefore, competition is the mechanism for effective control (Hood, 1998). In this sense, the individualist's freedom from control by others facilitates their attempts to control others, making the size of his following the measure of this success (Douglas, 1982). "Individuals are left to their own devices in a survival-of-the-fittest competition-ruled world" (Garcés, 2015, p. 98). Consequently, the mechanism per excellence to reach optimal arrangements is the market. Markets are the ones able to self-organize and reach equilibriums when all individuals are out for themselves, constituting the space where a trial-and-error approach to life takes place (Thompson, 2003). As a result, from an individualist perspective, organizations are an 'arena' (Hood, 1998).

Egalitarian rationality: The group above the one

The third rationality is found at the intersection of low grid and high group. This means that the egalitarian way of life is characterized by extraordinarily strong group membership and rather narrow or superficial external prescriptions, if any. As a result, roles within the collective are far from specific, if defined at all, leaving individual choices to the determination of the group. Human nature, for those who subscribe to this way of life, is inherently associated with caring and sharing, only corrupted by inegalitarian institutions (Thompson, 2003). In this sense, egalitarians construct the group as opposed to 'the other' and against institutions that pose a threat to equality (i.e. hierarchies and markets). Within the collective, absent role differentiation, human relationships turn ambiguous (Douglas, 1982) and there is a relative increase in uncertainty. The state of anarchy induces decision-making to take place by consensus, making conflict resolution laborious and resorting to the exclusion of members as the solution (Thompson & Ellis, 1998), particularly in the case of dissidence. In the absence of authority, the mechanism to verify and assess the fulfilment of commitments is mutuality (Hood, 1998). It is no surprise, there fore, that these groups are likely to be small (Douglas, 1982). Because of the above, from an egalitarian worldview, organizations are considered as "collegial' (Hood, 1998).

Fatalistic rationality

The fourth and final rationality is made up of high grid and low group. As such, the fatalist social arrangement is determined by a weak group membership and a wide and deep presence of external prescriptions. While the individual freedom of choice does not depend on the group, it does depend on the classification established by the social system (Douglas, 1982). However, that classification is made by someone. Since fatalists are simply subject to it and not their makers, they do not belong to the group wielding the power of institution-making4; i.e. they are rule-takers, not rule-makers. According to this way of life, human nature is seen as "fickle and untrustworthy" (Thompson, 2003). Hence, contrived randomness is the control mechanism used for those pertaining to this way of life (Hood, 1998). Given the fact that fatalists see their freedom of choice restricted externally, limited against their will, never with their consent, the world is regarded as uncertain and so are people. Therefore, the world is unpredictable, and individuals see themselves as ineffectual; regardless of their efforts their goals are unlikely to be accomplished. So, it is best not to even try. Thus, for fatalists, organizations are 'gaming machines' (Hood, 1998).

Four worldviews of integration

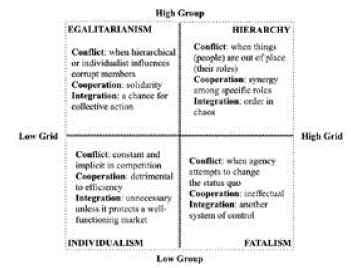

As stated above, the case for wicked problems builds on an interpretivist epistemology. As can perhaps be gathered from the above, cc cultural theory embraces it as well. This means that, from this perspective, important concepts, particularly those essentially contested ones, have different meanings and interpretations depending on their worldview. For current purposes, this is especially salient in the case of the identification of a problem and its (re)solutions. Therefore, in order to suggest how regional integration is interpreted by (what it means for) each way of life, this section discusses two concepts inherently relevant to international relations, to wit, conflict and cooperation (Nye & Welch, 2014). A summary of this discussion, illustrated in the respective quadrants, is presented in Figure 3.

Source: The author

Figure 3 Integration, Conflict and Cooperation from Four Rationalities or Worldviews.

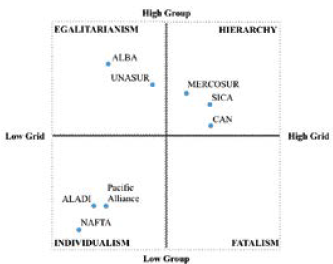

Additionally, building on the conceptual elaboration, this section introduces Latin American regional integration projects and places them within the cc cultural theory scheme.

The analysis is based on the current state of affairs of these initiatives. That is, it is informed by their current regulations, structure, decisions and some of the other latest relevant events associated with them. Therefore, the insights gained from this exercise are certainly subject to change as these initiatives themselves change. Importantly, this analysis does not study all Latin American regional integration efforts exhaustively, neither does it scrutinize them profoundly as it does not need to do so. For the purposes of the argument, suffice it to explore what are arguably the main integration mechanisms in the region and their central characteristics in order to illustrate where some of the most relevant notions of regional integration are likely to be located (on the four worldview quadrants), on the basis of their dominant rationality5. Moreover, since all mechanisms are likely to have all worldviews, placements are carried out based on a relative criterion; that is, by identifying whether each integration system adheres more to one than to the others. As in the case of the conceptual discussion, an illustration is provided in Figure 4.

Hierarchical

Integration, for hierarchists, is an opportunity to bring order to an otherwise anarchical international system. From this perspective, that order is brought in terms of the specialization of tasks and responsibilities given to member states. Moreover, within the system, there has to be an authority to create the institutions ruling it. So, it also represents an opportunity to seize power by becoming the authority that imposes that order (and imposes its own sense or notion of 'order'). In this sense, order is regarded as everything being in its right place (from the perspective of those in power). The source of conflict, in this worldview, is things out of place (Thompson et al., 1990). The latter are considered as threats to the status quo, which are caused by contamination from below.

In this sense, integration mechanisms adhering to this perspective present law-abiding nations that have, to different extents, self-imposed institutions in order to tackle certain issues. Therefore, given its ability to harmonize interactions and reduce uncertainty, the system is privileged above all else. Accordingly, all action, including cooperation, is seen as useful if it observes established institutions and, as such, contributes to the status quo. Moreover, authority is present at every stratum and legitimate as long as it comes from above. Whether from above or below, attempts to challenge the established authority are regarded as a threat to the system, as things out of place, and therefore produces conflict. Hierarchical systems have a wide range of well-categorized tools to deal with such challenges (Douglas, 1982).

In order to identify those Latin American projects that can be associated with this rationality it is necessary to look at their internal organizational scheme. The more complex the structure of the integration mechanism, the more likely it is to answer to higher specialization. In this sense, those initiatives that have institutionalized bodies and entities to deal with specific aspects show a higher degree of specialization than those who have not done so. Integration mechanisms that have incorporated Tribunals or Courts for conflict resolution and Parliaments or Legislatures for regulation making are some of the most relevant examples; others include commissions, institutes and similar entities dedicated exclusively to fulfil a specific function. Hence, perhaps the most noteworthy examples in the region are the Common Market of the South (MERCOSUR), the Andean Community of Nations (CAN) and the Central American Integration System (SICA). All of these mechanisms have transformed their structures incorporating further formal specialization by institutionalizing bodies in charge of fulfilling very well-defined mandates. In this sense, the MERCOSUR has a functioning Permanent Review Court as well as the MERCOSUR Parliament (MERCOSUR, 2016; Quijano, 2011), CAN has the Andean Parliament and the Justice Tribunal of the Andean Community (CAN, 2018; CAN -General Secretariat, 2009), and SICA has the Central American Parliament and the Central American Court of Justice (SELA, 2014; SICA, 2018).

Individualistic

Individualists regard integration as unnecessary. The international system is an arena, where everything is up for grabs and competition governs. In simple words, it is an anarchical system and so it should be. Within such arrangement, the benefits of any endeavor go the most cunning players. Therefore, rewards are based on individual skill and merit, not specific roles predetermined by someone else. In the absence of a central authority, conflict is a constant possibility since each state can do as it pleases, exercising its virtually limitless autonomy. The enjoyment of this freedom in a well-regulated market can induce individualists to engage in associations showing hierarchical features (Lockhart, 1998). Even in those arrangements, however, there is a primacy of the individual, where loyalties lie in relation to the individual, not to the system.

In this context, survival becomes the main issue and cooperation can be tolerable to the extent that it provides an additional tool to guarantee one's existence and further one's goals. Thus, any cooperation at all is self-interested. As such, integration initiatives are spheres where power is sought and exerted both horizontally and vertically. Vertically, they provide a legitimized field for negotiation and bargaining that can generate relationships of domination with like-minded states and even potential competitors. Horizontally, since they can contribute to the consolidation of one's power, they can neutralize that of potential and actual competitors. In this way, although opposed to external authority, individualists can favor integration when there is an opportunity to be the authority themselves. However, under these conditions, authority is con-junctural and so are allegiances.

Perhaps the most evident regional integration efforts are those affiliated to the classic trade-based integration initiative. These projects, best portrayed by Bela Balassa's theory (1961a, 1961b), seek to widen and deepen the reach of the free market at the international level. Thus, those integration initiatives in Latin America subscribing to this model are to be located within this worldview. Two caveats are pertinent presently. First, current integration mechanisms are unlikely to focus exclusively on trade but incorporate other dimensions. Therefore, what matters is the disproportionate focus that trade receives within them relative to other aspects. Second, it is worth mentioning that various initiatives were originally conceived solely, or primarily, in economic terms (e.g. the Andean Community and MERCOSUR) but they have distanced themselves from that one-dimensional approach and have incorporated social, cultural, environmental and other dimensions. Thus, in this brief exploration, their current shape is taken into consideration. In this sense, perhaps the best illustrations of Latin American integration initiatives are the Pacific Partnership and the Latin American Integration Association (ALADI) (ALADI, 2018; CEPAL, 2012). Leaving somewhat the region and looking northwards, the integration effort that best epitomizes this worldview is the NAFTA (Arenas-García, 2012) (as of October 2018, rebranded as USMCA).

Egalitarian

From an egalitarian perspective, regional integration is an opportunity to project their rationality or way of life over the system and potentially generate a more equal state of affairs in an international system dominated by other ways of life. Egalitarian integration mechanisms are, therefore, characterized by consensus in decision-making, not by imposed governing rules. The latter are considered as misguided attempts by hierarchical and individualist influences located outside the collective. Such efforts are fought against with determination seeking to consolidate even further the cohesion of the group, nurturing an identity built in contrast to 'the other' (ways of life) (Thompson et al., 1990). Conflict usually raises when the threat comes from within and questions equality. Should this happen, egalitarian initiatives prefer dialogue and, in extreme cases, resort to exclusion of threatening members.

Egalitarian integration arrangements, therefore, are made up of nations that consider themselves equals and behave that way. There is a notorious absence of authority, as any effort in that sense threatens equality. This situation makes decision making more cumbersome as consensus is required. Even though those decisions may take longer, they are also likely to be taken with more conviction. To be sure, this does not guarantee decisions to last longer, since convictions are political, and heads of government are only temporary. Nevertheless, conviction is likely to make commitments more forceful, creating thereby a path on which future decisions may be dependent. Cooperation, therefore, is not a matter of negotiation and bargaining, a tit-for-tat, but rather a demonstration of solidarity among equals. Because of these characteristics, egalitarian arrangements are often small and, therefore, usually found within wider systems like markets and hierarchies, in opposition to which their identity is generated and consolidated.

From all the Latin American integration mechanisms, perhaps those most associated with this worldview are the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of our America (ALBA) and the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR). This does not necessarily have to do with the decision-making procedures within their organs, as consensus is also adopted in other initiatives such as MERCOSUR. Instead, what identifies ALBA and UNASUR with an egalitarian rationality is the solidarity expressed in their founding treaties and their efforts to shorten the distance between bigger and smaller states (Bernal-Meza, 2013; Couriel & Moreira, 2013; Espinosa 2013; Regueiro & Barzaga, 2012). As suggested by cc cultural theory, these mechanisms were conceived and have developed an identity by differentiating themselves from those based on trade and the free market (or 'the other'). In fact, UNASUR and ALBA were explicitly born from the ashes of the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA), which sought to expand NAFTA'S market-based and individualist rationality to the whole region but never saw the light of day.

Fatalistic

A fatalist rationality sees regional integration as one more instance from which some states exert power over others. Fatalists are the latter, never the former. Those in control dominate the system and establish the rules governing the mechanism. Fatalists see themselves as rule-takers, not rule-makers. Nevertheless, they are resigned to this fact and accept it as an inevitability. Those who govern them are states adhering to individualist or hierarchist rationalities and, as such, they are actively pursuing and exerting power. In this context, there is no intention to change the state of affairs, no interest in gaining power, and no attempt to play a different role. Since others have the power, they are merely subject to their will. This makes the international system unpredictable for them and any effort to change it is likely to deliver unexpected and damaging consequences. Since the agency of fatalists is virtually absent, they do not experience conflict. Conflict is a thing of those either wielding power or in search of it. Hence, conflict is likely to take place whenever agency is exerted in general, and when it seeks to modify the status quo in particular.

For fatalists, cooperation is also inexistent. There is no point in cooperating because that means taking risks, which are not likely to pay off (Thompson et al., 1990) since they lack the power to make things happen. To reiterate, things happen to fatalists. Because of all this, integration is a futile effort to them, and it would not be their initiative. They have little to gain from it since, for them, it really is one more mechanism for others to exert power over them. Thus, if they engage in it is because they feel compelled to do so and see no other choice. Consequently, fatalists do not necessarily have one integration mechanism representing them but are likely to be found in many, perhaps all, regional integration initiatives, particularly among those groups relatively disem-powered.

This last insight is of the utmost importance. It highlights the fact that within one integration system not all members share the same worldview. The implication is that multiple notions of integration are competing within the same mechanism, reflecting all rationalities constantly competing with one another. This undergirds the proposition with which this article started, that Latin American integration is a problem and a wicked one at that. The consequences of this plurality within each Latin American integration mechanism is discussed next.

Plural rationalities, wicked problems and clumsy solutions

cc cultural theory "(...) acknowledges that our world, nations and cultures, in themselves, are pluralists" (Aphelthaler & Domicone, 2008, p. 48). This means that it is quite likely for there to be more than one culture within one integration system, even though one dominates it6. In fact, there is more than one culture within one nation. Arguably, these are represented by the always competing rationalities from which people choose periodically in democratic nations to reflect their preferences domestically and internationally, when they elect governments. Since memberships, decisions and actions taken within integration systems reflect the position of member states, and the latter, in turn, are led by democratically elected governments (at least in Latin America), integration systems are influenced, to an extent, by the worldview of those in office at any given moment in time. Consequently, the effect of different and changing interpretations of what regional integration is and ought to be can be attested in at least two aspects: membership and policy.

Regarding membership, even at a point in time, a state abides by their rationality only imperfectly or, in other words, although they may have one dominant rationality, they have others as well. The fact that different states are members of different integration initiatives, each showing a distinct worldview shows that member states have competing notions of integration. It could be argued that this may also ensue due to the fact that they, at different times, have subscribed to different worldviews (different governments have endorsed different notions of integration). And, should this be the case, multiple membership, rather than a sign of multiple rationalities, points to the difficulties of leaving one integration mechanism due to the commitments acquired and path dependency. This line of argument, plausible as it may seem should not be overstated, especially in light of the fact that some states have indeed done so and have left integration initiatives. Such instances could constitute evidence of both the dominance of one rationality over the others at any given time and the change in the shaping of rationalities and worldviews, leading to it. Telling examples are the departure of Chile and Venezuela from the can and, more recently, the announced departure of Colombia and Ecuador from UNASUR, and the distancing of Ecuador from ALBA.

Apropos of policy, change in rationalities within an integration system can also be observed in changes regarding its structure, purpose, decisions and actions. Latin America has also experienced this kind of change in its integration initiatives. One example could be the changes within the can in order to revamp it (Arenas-García, 2012). Another example could be the changes within MERCOSUR. Although initially incorporated with economic aims, to create a common market (MERCOSUR, 1991), in time it expanded its scope so as to include social aspects such as education, health and migration .

Whether with the departure of a member state or modifications within the integration mechanism, it seems fair to say that change answers to a perceived surprise or problem by the dominant rationality in member states or within the initiative itself. These events have arguably happened when the mismatch between what is and what ought to be is big enough. cc cultural theory explains such change in terms of a change in the shaping of rationalities, particularly via a change in the dominant one. This is because rationalities are constantly competing with one another and seeking to persuade more people, enough so as to establish their worldview (Thompson et al., 1990). "Cultural theory assumes that these same four forms of organizing and perceiving are interacting -forever merging, splitting and re-combining- in unpredictable ways at each conceivable level of social organization. Thus, four straightforward organizational principles can result in an endlessly changing, infinitely varied and complex social world" (Verweij, 2011, p. 38).

So far so wicked. The argument so far has managed to better organize some of the different current worldviews regarding Latin American integration, reducing thereby some of its complexity, but it remains a wicked problem. That is, it remains an ill-defined problem lacking one definitive solution and having conjunctural resolutions since "[s]ocial problems are never solved. At best they are only re-solved-over and over again" (Rittel & Webber, 1973, p. 160). In this sense, according to the literature, contrary to tame problems, which can be solved by 'elegant' solutions, wicked ones like Latin American integration can only be addressed by 'clumsy' solutions.

Clumsy solutions respect the plurality inherent in social (wicked) problems. Since these problems are perceived from different worldviews, which make sense out of them, clumsy solutions seek to understand the various interpretations and cater for the four ways of life. Arguably this already hints at the most fundamental difference between tame and wicked problems. While the former sees problems as clear-cut, uniquely and precisely defined and objective, therefore requiring one exact and definitive solution, the latter regards problems as dependent on the world-view of those perceiving it, subject to interpretation, thus potentially demanding multiple solutions. From a philosophy of science perspective, the first may be associated with positivism and the second with interpretivism. This insight can prove valuable when seeking to address wicked problems.

A clumsy solution is one that incorporates the interpretations of all ways of life, respecting thereby their current structure. Hence, clumsy solutions "[...] are creative, flexible mixes of four ways of organizing, perceiving and justifying that satisfy the adherents to some ways of life more than other courses of actions, while leaving no actor worse off" (Verweij et al., 2006, p. 840).

Clumsy solutions, by seeking to understand all views instead of talking past each other, recognize as essential contestation that which seems irreconcilable contradiction (Verweij et al., 2006). Accordingly, the locus of attention for clumsy solutions is necessarily twofold: in the ends and the means. On the one hand, they pay due attention to the effectiveness of results. On the other, it also cares for the legitimacy of the process to obtain them. Consequently, the arrangement that integration ought to take in order to overcome the challenge of ever changing multiple rationalities has to be both fluid as well as contingent, making it thereby 'clumsy' (Verweij, 2011; Verweij & Thompson, 1998).

In light of the above, clumsy solutions are plural and conjunctural. There may be more than one clumsy solution at any given moment and sometimes none may exist (Verweij et al., 2006). When there are options, they tackle the wicked problem for the time being, settling the issue only temporarily. As can be gathered from this discussion, the interpretation of wicked problems depends on the dominant rationality and shaping of worldviews at a given moment. Since these arrangements are subject to change, so are clumsy solutions.

Importantly, clumsy solutions do not entail a relativist or an 'anything goes' approach to problem (re)solving. Not just any blend of rationalities or ways of life can be, regardless of any consideration, seen as a clumsy solution. The nature and quality of the engagement among rationalities as well as their interaction in producing the solution is of importance as well (Verweij et al., 2006). Hence, a solution, to be clumsy, has to at the very least: i) engage all rationalities; ii) harness their dialogue in a constructive fashion; iii) contribute to address the social problem; and, iv) do not leave any worldview worse off. Therefore, there is no map to follow in order to fix the wicked problem of Latin American integration but if these insights are duly considered, there may just be a compass to point towards clumsy solutions.

Conclusion

Latin America seems to be currently undergoing a transformation. At the international level, rather dramatic changes have been taking place. One telling example is the issue of regional integration. Some initiatives have lost the interest of state parties and others seem to have benefitted from this situation. In 2018, almost all state parties to UNASUR have expressed their concern regarding the mechanism and Colombia has already announced its departure, while Ecuador did the same in early 2019. The latter has also distanced itself from alba and, almost simultaneously, has sought membership in the Pacific Alliance, which denotes a quite different (perhaps even antithetical) idea of what regional integration means. Finally, in the wake of these restructuring, there is also the announcement of a new initiative: PROSUR, supported by seven countries (Chile, Colombia, Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador, Paraguay and Peru). These events suggest a shift on the notion of integration, of what it is and what it ought to be.

Thus, ideas about regional integration matter. Depending on the interpretations given to the notion of integration, different goals are set, and different policies enacted. The situation illustrated by ALBA, UNASUR and the Pacific Alliance is potentially exacerbated by the inclusion of other mechanisms such as MERCOSUR, ALADI, CAN, SICA, etc. This diversity in notions regarding Latin American integration increases when studying it historically since they have undergone significant changes from their inception to the current state of affairs. This makes it a problem in and of itself, but not any problem, a wicked problem (Garcés, 2018).

That Latin American integration can be usefully treated as a wicked problem is not a new argument. In fact, that case was made in this very forum in 2018 (Garcés 2018). In brief, wicked problems are mostly social problems and are characterized by being ill-defined without one precise and definitive solution. As such, they entail the difficulty of potentially presenting as many definitions and solutions as observers. Hence, this essay has not aimed to provide one additional definition of regional integration with any conclusive aspirations nor to adhere to an established one. This article has sought to build on that contribution by providing a framework to make wicked problems more tractable. In this sense, it has argued in favor of gg cultural theory. This framework focuses on individual freedom of choice and the dimensions that influence it; to wit, grid (external imposed prescriptions) and group (group affiliation effect), which take place as a matter of degree. Their combination produces four distinct and irreducible worldviews, ways of life, or rationalities: individualistic, hierarchical, egalitarian, and fatalistic. These are 'pure' positions or 'ideal types' and each one provides a different understanding of contestable concepts, including the idea of regional integration.

Hence, the argument presented here has fleshed out those interpretations and illustrated them by locating regional integration initiatives that arguably adhere to them. Thus, from a hierarchical perspective, integration is an instrument to bring some order to the chaos that is the anarchical international system by dint of specialization of functional roles. In this sense, MERCOSUR, CAN and SICA can be considered adequate examples. An individualist rationality sees integration as unnecessary unless it put to the service of a well-functioning market. Regional projects based on free trade such as ALADI, the Pacific Alliance and NAFTA fall within this category. The egalitarian worldview, in turn, regards integration as an opportunity to foster collective action based on solidarity. Perhaps the initiatives that illustrate this positions best are UNASUR and alba. Finally, for the fatalist way of life integration is nothing more than one more scheme for others to exert control over them. There is no illustration for this worldview because of its nature, but adherents to this way of life are likely to be found in all of the others.

This discussion hints to three important characteristics: coexistence, competition and change. Since these are ideal types, no integration mechanism is solely hierarchist, individualist, egalitarian, or fatalist. Regardless of the dominant rationality in the integration system at any given moment, there is likely to be member states that subscribe to different ones. Moreover, rationalities or worldviews are always competing with each other in a zero-sum game. The loss of adherents of one way of life means the gain of another. Telling examples of this is the transition of Ecuador from an alba supporter to a potentially Pacific Alliance member or the distancing of countries from UNASUR and their support of PROSUR. Finally, and in light of the above, both the dominant rationality of a system and the shaping of worldviews within it are subject to change. When there is sufficient discrepancy between expectations and reality, a different arrangement is likely to emerge. Presumably, the aforementioned changes in the region answer to this mismatch, as countries have perceived that some mechanisms provide more certainty (less surprise) better than others (in fact, criticism coming from many states against UNASUR is that it has failed to meet its goals).

Therefore, any analysis, such as the one presented here, is necessarily temporary, valid only as long as the current arrangement endures. The rather drastic changes that have taken place in late 2018 and early 2019 so suggest.

Furthermore, and as a consequence of the above, potential solutions are also diverse and conjunctural, that is, they are clumsy. Clumsy solutions are alternatives that address a wicked problem, taking into consideration all relevant worldviews, harnessing them in constructive dialogue and not leaving any way of life worse off. The implications are fourfold. First, clumsy solutions are concerned with the results as well as with the process that delivers them. Second, there may be various clumsy solutions to a wicked problem at a time and sometimes there may be none. Third, clumsy solutions should not be associated with 'relativism' or 'anything goes' as they must meet, at least, the aforementioned criteria. Finally, to reiterate, because of the above, clumsy solutions only (re)solve the issue for the time being. Under different circumstances, different arrangements of ways of life, a different clumsy solution may be warranted.

This analysis has considered Latin American integration itself as a wicked problem and, thus, it has studied it directly from a grid-group gg cultural theoretical perspective. It has used a heuristic crossroads of sorts to tackle the Latin American figurative crossroads. The aim has been to shed further light on the issue and provide an approach that takes the inherent plurality in wicked problems seriously, rather than to provide a solution. Therefore, even though the picture is not completely in focus, contours seem to be sufficiently differentiated.

What is the shape Latin American integration should take? Since it is a wicked problem, that is a question for debate in the public sphere. In that fruitful undertaking, this essay has sought to provide a small academic contribution. Some interesting insights have been gained from this exercise signaling promising directions of travel so as to further what seems like a necessary and urgent discussion. Perhaps the most evident way forward, just as in the argument regarding Latin American integration as a wicked problem, is realizing that each integration mechanism can be studied individually in order to identify the current arrangement of rationalities within it, so as to take one more step forward towards clumsy solutions.