Introduction

Maritime piracy is a long-standing threat or risk for security. In fact, what we see today globally is a contemporary version of an ancient issue. Patricia Risso (2001), in an article on culture and maritime piracy, concludes that the age of piracy is evidenced by language. The author points out that the word peirates in Ancient Greece referred to a "broad range of maritime violence in the multi-coastal environment of Greece and the wider Mediterranean" (2001, p. 296) and that its evolution to pirate in Ancient Rome identified an "enemy of all humanity" (2001, p. 297). Other examples are the Dutch term freebooter, which referred to a "rogue adventurer or mercenary" (2001, p. 297), the French word buccaneer to refer to "a pirate in the Caribbean" (2001, p. 297), and the Latin word corsair, which means "pirate in the Mediterranean" (2001, p. 297).

As for the former examples, maritime piracy was active in ancient Mediterranean civilizations; therefore, we might suppose such threat or risk is inherent to maritime trading. Piracy is treated as a criminal matter that leads to mercenaries and pirates' financial gain. Today, authors such as Bolanos (2013) and Morales (2014) characterize maritime piracy as oil theft, illicit trafficking, irregular migration, and illegal exploitation of marine resources.

At present, two sources provide a legal definition of maritime piracy. First, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in 1980 defined "piracy" as an illegal act of violence of detention or predation for personal purposes. It is performed from a private ship or aircraft against another ship, aircraft, people or their belongings at high sea or waters with no state jurisdiction, implying the voluntary participation, incitement, or facilitation. Second, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) created in 2009 the Code of Practice for the Investigation of Crimes of Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships. It quotes the UNCLOS to define maritime piracy and contributes the classification of "armed robbery against ships," including their threatening actions; that is to say, when the felony is not yet committed or when it may not qualify as maritime piracy. Besides, it expands the location to inland waters, archipelago, and territorial waters.

The International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), on its annual reports1-Piracy and armed robbery against ships-lists 7,671 total attacks and 12,957 crew victims of violence between 1991 and 2019. These reports classify piracy attacks per region and location, status of ships during the attack, type of attack, type of arm used, type of violence to crew, nationality of ships attacked, and type of vessel attacked. It should be noted that attacks are divided into actual and attempted.

By analyzing Risso's (2001) signifier and meaning, UNCLO'S and IMO'S legal perspective, and ICC'S classification and definition, we may present the following research question: How can maritime piracy be characterized as a threat? The answer to it involves the analysis of the categories and features pointed out above; therefore, piracy is addressed in all its temporary extension and total attacks per region and location, type of attack, type of arm, type of violence to crew, nationality of ships attacked, and type of vessel attacked.

From the perspective of International Studies, maritime piracy is marginalized in its full characterization, thus becoming the motivation to pose the question and answer it. An example of it is the World Politics handbook. Its fifth edition (Kegley & Wittkopf, 1995), in the part of "non-state actors," mentions international agencies and multinational corporations and, for "force employment," shows inter-state and intra-state wars. In this case, nonstate actors exclude threatening agents, and coercive force is connected only to wars, which is very typical of the 1990s global security, even though The Naples Political Declaration and Global Action Plan already existed in 1994.

As for "non-state actors," the ninth edition (Kegley & Wittkopf, 2004) maintains the same information as in 1995 and, for "armed conflict," adds terrorism. The latest edition (Kegley & Blanton, 2017) includes crime for "non-state agents," exposing maritime piracy, and maintains the view of its previous edition for "armed conflict." This change is explained by Al-Qaeda's attack against the United States of America on September 11, 2001, and the effective date of the Convention against Transnational Organized Crime in 2004, where safety and security priorities were reformulated at the global, regional, and State levels. Therefore, the coercive action-use of force and armed conflict-against crime-non-state actor or nonstate agent-is inherent to global security in the 21st century. As for maritime piracy as a threat, its appearance is novel and marginal, despite its long historical existence and current relevance.

This article is divided into two sections. The first section contains the theoretical discussion that supports the analysis of existing data on threats, based on academic sources from the Copenhagen School. The second section analyzes the ICC reports from 2000 to 2019, which are the primary sources reporting maritime piracy internationally since 1991, together with tables and figures containing processed information. Finally, the conclusion presents the answer to our research question.

Threats as a theoretical issue

The Copenhagen School provides one of the most influential perspectives on security studies. Hampson (1998) and Smith (1999) highlight that their approach is broad and deep, including sectors such as the environment, economy, and society. Therefore, this School can provide a clear explanation of the security priorities established during this century.

One of the books of this School, People, states and fear by Barry Buzan (1991), points out that security is the state's ability to maintain its independent identity and functional integrity, while insecurity is the sum of all vulnerabilities and threats. State vulnerability (Buzan, 1991) is classified as high, particular, or relative according to its military power and institutional cohesion. For example, as the author points out, Angola is weak in power and cohesion, being highly vulnerable to all kinds of threats; Japan is strong in power and cohesion, being relatively invulnerable to all kinds of threats; Singapore is weak in power and strong in cohesion, being particularly vulnerable to military threats; India is strong in power and weak in cohesion, being especially vulnerable to political threats.

As for threats (Buzan, 1991), the idea is sustained that they have difficulty being inserted in a subjective and objective reality, making it impossible to perform any measurement, even more for being imperceptible. Another difficulty lies in distinguishing between normal competence in the international system and actual threats, which becomes evident when trivial and routine affairs become serious and extraordinary. Then, insecurity presents an internal variability of qualified vulnerability regarding military power and institutional cohesion and, at the same time, an external variability of threats whose qualification or quantification is complex. The author groups security problems into five sectors: military, political, economic, social, and ecological. From the military sector, the highlights are that:

The level of military threats varies from harassment of fishing boats, through punishment raids, territorial seizures and full invasions, to assaults on the very existence of the populace by blockade or bombardment (...) threats to allies, shipping lines (...) military threats occupy a special category precisely because they involve the use of force (Buzan, 1991, p. 116).

Two ideas arise about the military sector based on the quote presented above. First, the minimum requirement for the existence of a military threat is the coercive use of force. Second, the expression of a military threat does not involve the State armed forces only; on the contrary, it is quite heterogeneous and includes private agents, like in maritime piracy. The Copenhagen School's book Security: A new framework for analysis by Buzan et al. (1998), contains a complete chapter on the military sector. Its centrality leads to the affirmation that a varied kind of security problems affect the military sector, creating a tendency in underdeveloped countries to increase military actions against non-military threats. It should be noted that the military sector has great explanatory capacity at the regional and local levels, being involved in brute force events whenever there is an increase of "military function" (Buzan et al. 1998, p. 49), such as protecting the civil population in natural disasters, supporting the governments in their public policies, and facing crime.

Returning to People, states and fear, it characterizes threats by their intensity level, including diffuse or specific identity (understood as the agents exerting the threat and their resources); distance or closeness in space (the one that separates the threat from its objective); distance or closeness in time (that the threat needs for its attack); high or low probability (as measured according to the frequency of occurrence); high or low impact (the costs of the threat being effective in its attack); historically neutral or extended (regarding its history) (Buzan, 1991). As a result, we obtain an understanding of the behavior of a threat, in other words, we go from the difficulties of a subjective view to qualification and quantification based on reality, not on perception.

Complementing the idea of threat intensity, the Copenhagen School's book Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security by Buzan and Waever (2003) proposes a regional view to understand security. The authors formulate the regional security complex theory based not only on territory and power materialism, but also on constructivism regarding the political process of interactions. They achieve explanatory capacity when understand security as the place where national and international security interact, that is, regions, and the place where States cannot be considered autonomous. About intensity, both have the understanding capacity to locate the threatening agent and indicate its probability, impact, and history.

Summing up, the security of maritime trade is affected by a lack of both control over its ships and integrity of its operation. Insecurity expressed as vulnerability is the States' incapacity to confront maritime piracy, while insecurity expressed as threats is equal to maritime piracy's quantity and quality. In the military sector, this is reflected in the coercive and heterogeneous features of these threats; the region interprets the agent, distance in space and time, probability, impact, and history of the threat.

Annual reports on maritime piracy

During 2000, maritime piracy increased due to seven factors, according to Peter Chalk (2008): increased traffic of maritime trade, maritime congestion in bottleneck zones, the Asian financial crisis, deficient maritime surveillance, weak coast and port security, corruption of national justice, and proliferation of small weapons. In short, this current threat resurges with an economic crisis, increased maritime trade, and weak punitive response; when the threat originates, it later varies within regions and countries.

For its part, as Fernando Marin (2011) indicates, the United Nations Security Council voted a series of resolutions to face this threat, namely, Resolution numbers 1814, 1816, 1838, 1846, and 1851 of 2008, which intended to protect maritime convoys of the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) from maritime piracy in the Somali coasts. Years later, through Resolutions number 1897 of 2009, 1918, and 1950 of 2010, they extended previous resolutions' dates and functions.

This initiative had good but circumstantial results. Piracy went down considerably between the end of 2010 and the beginning of 2011. However, as Ignacio Frutos (2012) points out, piracy adapted and went from the assault on small ships to the assault on big ships and the kidnapping of their crews. As he explains, this adaptation occurred because the Somalis saw piracy as a way out to their national economic crisis and as an alternative for employment, group identity, and social status. This adaptation is also explained by the coercive response, as Pablo Moral affirms (2015), as the European Union's Operation Atalanta that came into effect in 2008 and the NATO'S Ocean Shield-current between 2009 and 2016-, conditioning piracy actions.

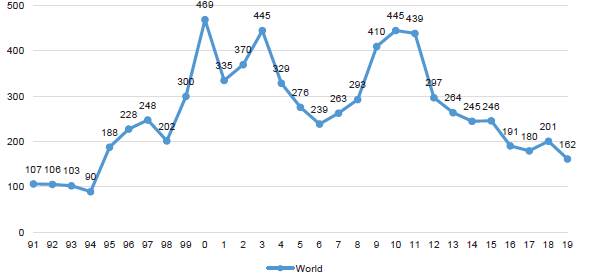

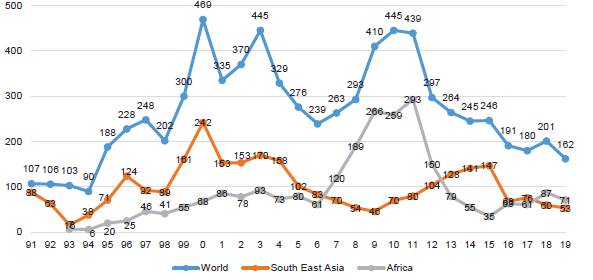

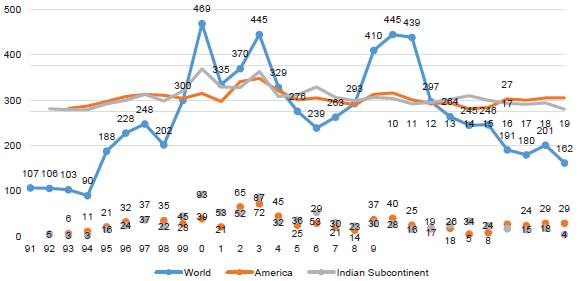

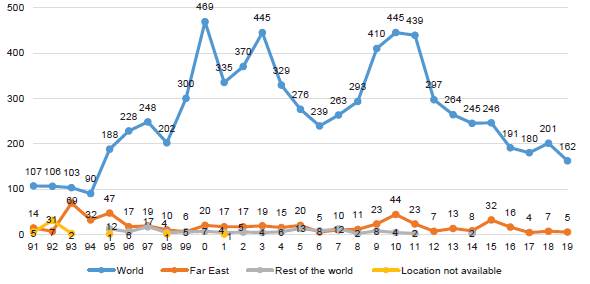

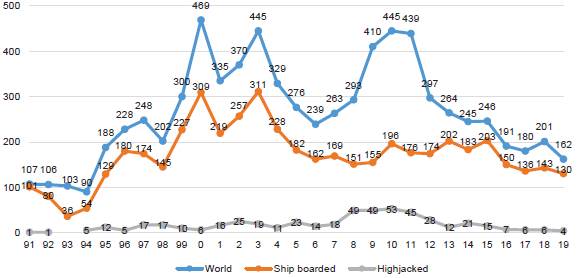

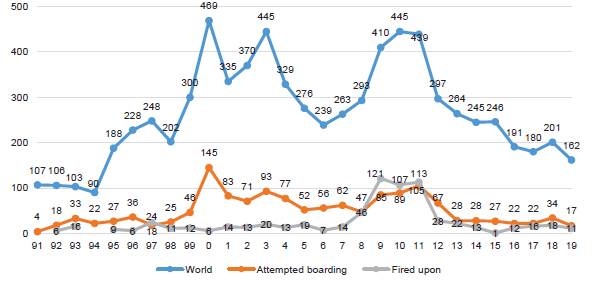

The ICC annual reports contain information from 1991 to 2019. From the most general, the total attacks mark a first increase period between 1998 and 2003 and a second increase period between 2006 and 2011 (Table 1; Figure 1).

Table 1 Total attacks by region 1991-2019

| Region | Number of cases | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Southeast Asia | 2,900 | 37.80 |

| Africa | 2,467 | 32.16 |

| Indian subcontinent | 845 | 11.01 |

| America | 760 | 9.90 |

| Far East | 537 | 7.00 |

| Rest of the world | 121 | 1.60 |

| Location not available | 41 | 0.53 |

| Total | 7,671 | 100 |

Source: Own elaboration.

Piracy location, that is, the total attacks by region and location provide a regional, state, or location panoptic view, with absolute and relative figures (Tables 2, 3, and 4; Figures 2, 3, and 4).

Table 2 Total attacks by location 1991-2019

| Location | Number of cases | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Indonesia | 1,800 | 23.46 |

| Somalia/Djibouti | 616 | 8.03 |

| Nigeria | 515 | 6.71 |

| Bangladesh | 465 | 6.06 |

| India | 324 | 4.22 |

| Rest of the world | 3,951 | 51.52 |

| Total | 7,671 | 100 |

Source: Own elaboration.

Table 3 Total attacks by location 1998-2003

| Location | Number of cases | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Indonesia | 609 | 28.17 |

| Bangladesh | 204 | 9.61 |

| Strait of Malacca | 139 | 6.55 |

| India | 133 | 6.27 |

| Malaysia | 87 | 4.70 |

| Rest of the world | 949 | 44.7 |

| Total | 2,121 | 100 |

Source: Own elaboration.

Table 4 Total attacks by location 2006-2011

| Location | Number of cases | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Somalia/Djibouti | 439 | 21.01 |

| Indonesia | 222 | 10.62 |

| Gulf of Aden | 207 | 9.90 |

| Red Sea/ Gulf of Aden | 155 | 7.41 |

| Nigeria | 152 | 7.27 |

| Bangladesh | 125 | 5.98 |

| Red Sea | 79 | 3.78 |

| Malaysia | 79 | 3.78 |

| Rest of the world | 631 | 30.25 |

| Total | 2,089 | 100 |

Source: Own elaboration.

For the total timeframe between 1991 and 2019, the regional number results separate the "rest of the world" and "location not available" from other categories due to their low figures, reaching only 2.13 % of cases. On the contrary, regions of the highest importance are Southeast Asia with 2,900 cases and Africa with 2,467 cases, totaling 69.96 %; second in importance is the Indian subcontinent, America, and the Far East together reaching 27.91 %. Location per country shows Indonesia (23.46) %, Somalia/Djibouti (8.03 %), Nigeria (6.71 %), Bangladesh (6.06 %), and India (4.22 %), confirming Southeast Asia, Africa, and the Indian subcontinent as the ones with the highest piracy levels.

The figures for regions with the highest levels show that the maximum records occur in Southeast Asia and Africa alternately; that is, there is a continuous inverse correlation, evidencing movement of maritime privacy. In fact, during 2006, 2012, and 2017 there is an overlap between these regions, with reverse increases and decreases. The maximum number of records for Southeast Asia were found in Indonesia with 609 cases and the Strait of Malacca with 139 cases for the first increase period (1998-2003); in turn, Indonesia had 222 cases for the second increase period (2006-2011); finally, Malaysia presented with 87 and 79 cases in both increase periods respectively. For its part, Africa had 439 cases in Somalia/Djibouti, 441 in the Red Sea/Gulf of Aden, and 152 in for the second increase period, showing an inverse correlation at the country level.

For the regions considered second in importance during the first increase period, the Indian subcontinent registered 352 cases, whose most typical examples were Bangladesh with 204 cases and India with 133 cases; for the second increase period, only Bangladesh appears with 125 cases. America registered 260 cases, where the most notorious cases were Ecuador adding up to 47 cases, and Brazil, with 42 cases; as for the second increase period, the region does not have any significant records. East Asia never went over 20 cases between 1996 and 2008, but in the second increase period, registered 90 cases, including South China Sea with 61 cases.

Africa and America exhibited similar characteristics initially, as both grew steadily between 1994 and 2004, their figures were always below 100 cases, and their highest numbers concentrated at the beginning of the century. However, both regions tend to differ for the second increase period. While America maintained records like the ones reached in 2004, Africa showed an unprecedented growth from 2006 on, becoming the location where most of the attacks took place and reaching maximum regional levels for the second increase period.

Similar situations are found in Southeast Asia and East Asia, as maritime piracy had its first cases in Asia, being both regions the only ones with attacks during 1991. Then, between 1992 and 1993, the threat was displaced. There were inverse correlations between both regions, with Southeast Asia showing an upward behavior, while East Asia showed numbers that progressively decreased over time.

From these facts, we can make five observations. First, between the decrease and increase during the time lapses, there was some geographical displacement of maritime piracy, and it took two years until it went up again. Secondly, the focus is Southeast Asia, Africa, and the Indian subcontinent from an accumulated perspective per region, state, or location. Third, from the regional point of view, we observed a displacement from Southeast Asia to Africa during the first and second increase periods, and after Africa reduced its piracy levels, there has been no other increase. Fourth, the regions considered as second in importance regarding piracy levels show dissimilar behavior in the increase periods: while the Indian subcontinent and America go up in the first increase period, East Asia shows growth during the second increase period. Fifth, endogenous factors might explain the differentiation between America and Africa and between East Asia and Southeast Asia.

From a theoretical discussion, maritime piracy regarded as insecurity is characterized by temporality and location. Additionally, high vulnerability (i.e., low military power and low cohesion) might explain displacements from one place to another in time and, at the same time, derive from the coercive response, as it is considered a threat to the military sector.

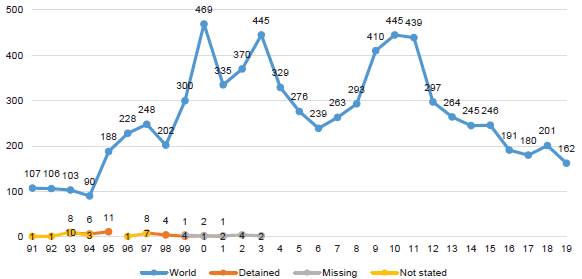

The types of attacks are the specific actions to attack merchant ships. For the full timeframe (1991-2019), "ship boarded" cases are the most common, not being outnumbered in any year and almost reaching 2/3 of the total, with 64.69 %. "Attempted boarding" cases are second, with 18.76 %, followed by the "fired upon" cases with 9.1 % and "hijacks" with 6.45 %. Lastly, and at an extremely low level, "detained," "non stated," and "missing" total 0.97 %. For the first increase period, "boarding" cases are the most important, followed by "attempted boarding". For the second increase period, the total number is almost reached by "boarding", "attempted boarding," and "fired upon" cases. In some years, "fired upon" cases outnumber "attempted boarding" figures (Table 5; Figures 5, 6, and 7).

Table 5 Total attacks by type 1991-2019

| Type | Number of cases | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Boarded | 4,962 | 64.69 |

| Attempted boarding | 1,439 | 18.76 |

| Fired upon | 698 | 9.10 |

| Hijacked | 495 | 6.45 |

| Detained | 41 | 0.53 |

| Not stated | 23 | 0.28 |

| Missing | 13 | 0.19 |

| Total | 7,671 | 100 |

Source: Own elaboration.

It is observed that, for the first increase period, the attacks in Southeast Asia mainly consisted of boarding and attempted boarding. During the second increase period, the problem was concentrated in Africa and the Indian subcontinent, implying a geographical movement and the inclusion of "fired upon" cases.

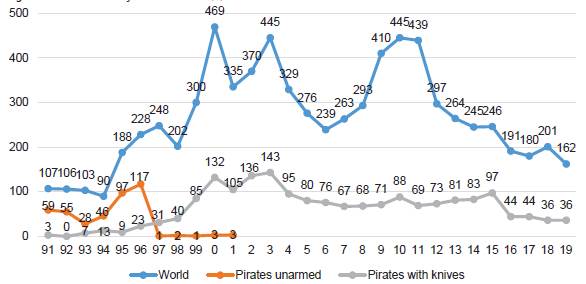

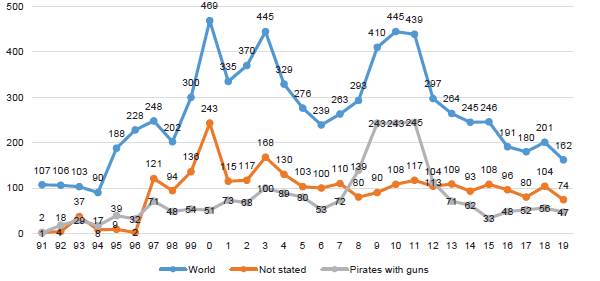

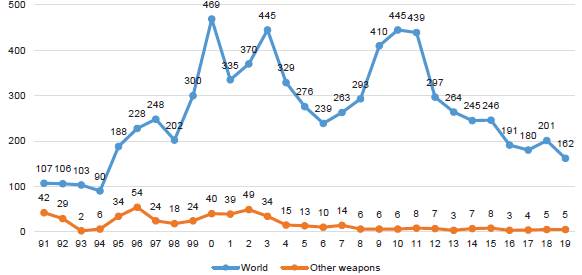

The total attacks by type of arm have a low, specific record, making the characterization of maritime piracy difficult, as "non stated" cases show very high figures with 34.69 %, that is, a little over one third. This figure is followed by "pirates with guns" (29.29 %), "pirates with knives" (23.92 %), "other weapons" (6.71 %), and "pirates unarmed" (5.37 %). The category "no arms" was reported as of 2001; therefore, its low occurrence in the full period (1991- 2019) and the low number of registered cases maket this category insignificant. Something similar occurs with other arms. For the first increase period, not stated weapons, knives, and firearms occupied the top positions. For the second increase period, the order changes, with firearms in the first place, followed by not stated and knives (Table 6; Figures 8, 9, and 10).

Table 6 Total attacks by arm 1991-2019

| Type | Number of cases | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Not stated | 2,662 | 34.69 |

| Pirates with guns | 2,247 | 29.29 |

| Pirates with knives | 1.835 | 23.92 |

| Other weapons | 515 | 6.73 |

| Pirates unarmed | 412 | 5.37 |

| Total | 7,671 | 100 |

Source: Own elaboration.

As a general observation, the arms registered in the first increase period in Southeast Asia are not stated, then knives and firearms; for the second increase period, in Africa and the Indian subcontinent, firearms take the first place, followed by not stated and knives.

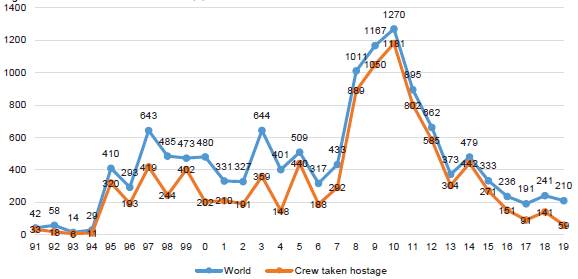

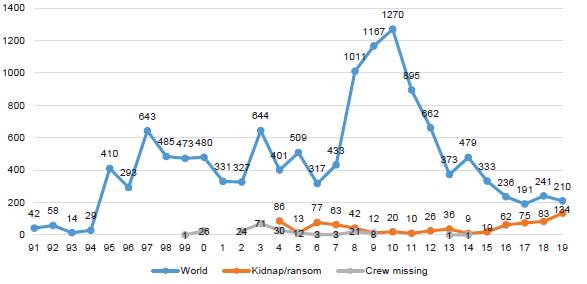

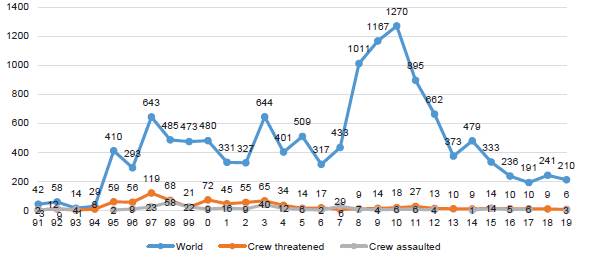

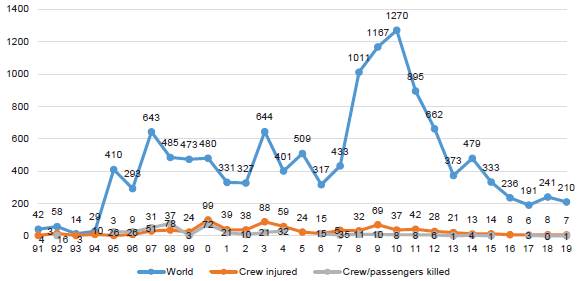

The type of violence to crew is different from total attacks, as its total number does not derive from piracy cases, but from the number of victims, reaching 12,957 between 1991 and 2019. In this case, the leading figures are 645 in 1997, 644 in 2003, and 1,270 in 2010, partially matching piracy increase periods, as the first figure belongs to a different year (Table 7; Figures 11, 12, 13, and 14).

Table 7 Violence to crew 1991-2019

| Type | Number of cases | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Crew taken hostage | 9,642 | 74.41 |

| Crew injured | 819 | 6.32 |

| Crew threatened | 801 | 6.18 |

| Kidnap/ransom | 767 | 5.91 |

| Crew/passengers killed | 416 | 3.21 |

| Crew assaulted | 311 | 2.40 |

| Crew missing | 201 | 1.57 |

| Total | 12,957 | 100 |

Source: Own elaboration.

Bearing in mind their specific characteristics, "crew taken hostage" crimes lead the victim population with 74.41 %, while "crew missing" represents 1.55 % of the total, concentrated between 2002 and 2009, having little importance. The remaining categories are below two digits: "crew injured" with 6.32 %; "crew threatened" with6.18 %; "kidnap/ransom" with 5.91 %; "crew/passengers killed" with 3.21 %, and "crew assaulted" with 2.40 %. For the first increase period, the crew being threatened, injured, killed, assaulted, and missing complete the remaining cases. The same occurs during the second increase period, though only the "kidnap/ ransom" type is included. Additionally, more crew members were injured during the second increase period than in the first one.

The observation, in this case, is that "crew taken hostage" is the primary type of violence exerted in Southeast Asia as the leading region during the first increase period; the same occurs in Africa and the Indian subcontinent during the second increase period, where "kidnap/ransom" appears as a new addition. Summing up this information, changes in the attack location also implied a change in the type of attack, type of weapon used, and damage to crew. Likewise, the data exhibited permits to partially refute the theoretical discussion, as this threat has quantities and qualities that make it objective reality.

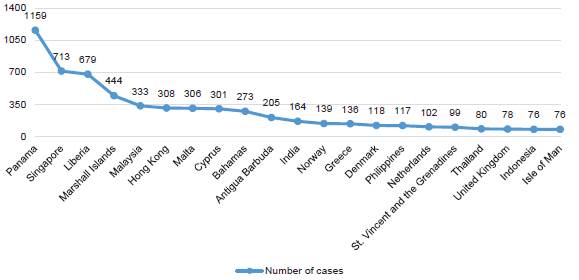

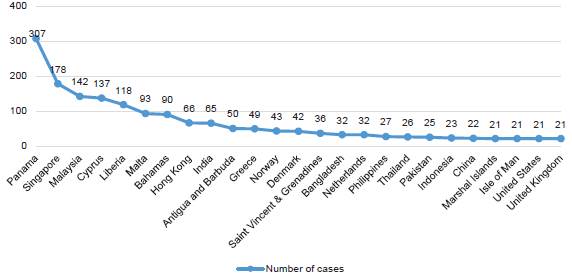

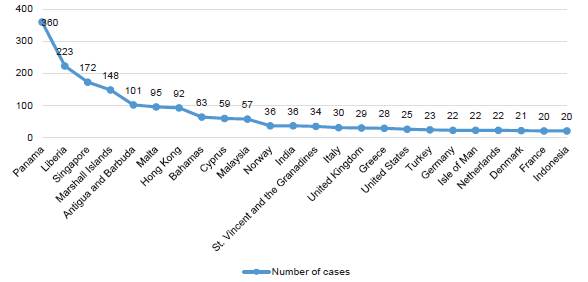

The nationality of ships attacked for the full timeframe 1991-2019) shows 136 registered nationalities plus those not stated. Like total attacks, 7,671 are merchant ships, where only 21 nationalities have at least 1 % of the cases, a minimum of 76 cases each, totaling 77.0 % (Figures 15, 16, and 17).

Note. Cases that account for at least 1 % of the total are presented. Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 15 Nationality of ships attacked 1991-2019

Note. Cases that account for at least 1 % of the total are presented. Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 16 Nationality of ships attacked 1998-2003 400

Note. Cases that account for at least 1 % of the total are presented. Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 17 Nationality of ships attacked 2008-2011 400

For the first increase period, with 2,121 cases, 25 nationalities hold at least 1 % of the total. For the second increase period, there were 2,089 cases, where 24 nationalities hold at least 1 % of the total. Nationalities for the full timeframe are contained in both increase periods. However, Bangladesh, China, the United States, and Pakistan were added during the first increase period, while countries such as Germany, the United States, France,

Italy, Malta, and Turkey were included during the second increase period, when the Philippines and Thailand disappear from the list.

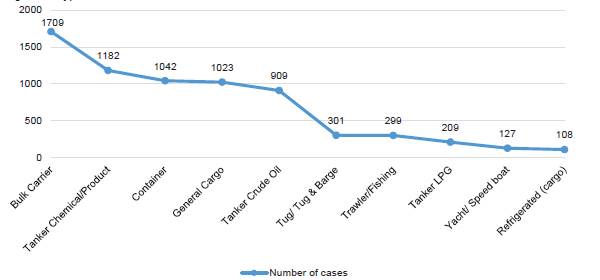

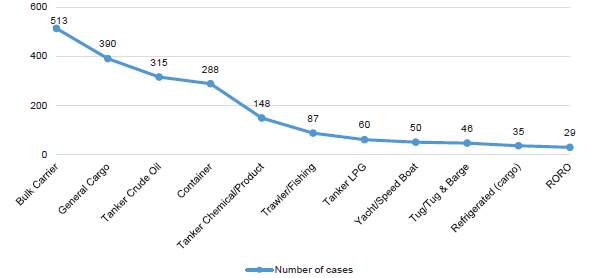

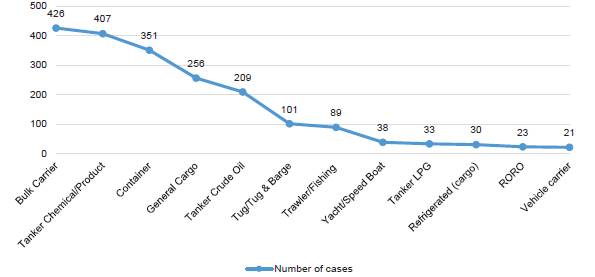

Finally, the type of vessel attacked shows that for the full timeframe (1991-2019), there are 70 types of vessels plus those not stated. As in the total number of attacks, 7,671 vessels were attacked; 10 have at least 1 % of the cases, i.e., a minimum of 76, reaching 90.07 % (Figures 18, 19, and 20).

Note. Cases that account for at least 1 % of the total are presented. Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 18 Type of vessel attacked 1991-2019

Note. Cases that account for at least 1 % of the total are presented. Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 19 Type of vessel attacked 1998-2003 600

Note. Cases that account for at least 1 % of the total are presented. Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 20 Type of vessel attacked 2006-2011 500.

The nationalities involved for the full time-frame are contained in both increase periods, although for the first increase period, Bangladesh, China, the United States, and Pakistan are added to the list. In the second increase period, Germany, the United States, France, Italy, Malta, and Turkey are incorporated, while the Philippines and Thailand are not on the list.

For the first increase period, 11 types of vessels were attacked, with at least 1 % each; that is, 1,961 ships under attack, representing 92.45 % of 2,121 types of vessels for the period. For the second increase period, 12 types of vessels were attacked, each with at least 1 %, representing 94.97 % of 2,089 for such period. The types of vessels for the full timeframe are contained in both increase periods, but during the first one, the "RORO" type was added, while during the second one, "RORO" and "vehicle carrier" were included.

Finally, through the classification of ships under attack, it is possible to recreate the intensity of maritime piracy, i.e., agents, space, time, probability, impact, and history.

Conclusions

In the introduction to this article, we concluded that, if maritime trade exists, so does maritime piracy, due to the age of its records-in Greece and Rome-, the name it has received over the years in different languages-Dutch, French, and Latin-, and its presence in different locations. Another idea presented here was that it meets the minimum requirement to be an illegal activity with revenues, which in terms of the UNCLOS' and IMO'S definition, is basically the same, especially when analyzing the ICC data.

As a first statement, the data analysis shows a timeframe that extends between 1991 and 2019, being the first increase period between 1998 and 2003 and the second increase period between 2006 and 2011. Consequently, the first answer to our research question (How does the 21st century's maritime piracy characterize as a threat?) is as follows, concerning this timeframe and based on the most reliable records on maritime piracy:

For the full timeframe between 1991 to 2019, the main regions affected are Southeast Asia and Africa, particularly Indonesia, Somalia/Djibouti, Nigeria, Bangladesh, and India. The principal types of attacks are "ship boarding" and "attempted boarding." The most common violence type is "crew taken hostage." The ships under attack come mainly from Panama, Liberia, and Singapore, and the most common ships under attack are bulk carrier, chemical/product tanker, container, and general cargo. The types of arms are not included, as these are distributed on a more equative, non-distinctive basis.

For the first increase period between 1998 and 2003, the most affected regions are Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent; in detail, the most affected States and locations are Indonesia, Bangladesh, the Strait of Malacca, India, and Malaysia. The most common types of attacks are "ship boarding" and "attempted boarding." The most common weapons used are knives, firearms, and other types. The type of violence most exerted is "crew taken hostage." As for the most common nationalities of the ships under attack, these are from Panama, Singapore, Malaysia, and Cyprus. The most attacked types of ships are bulk carrier, chemical tanker, container, and general cargo.

For the second increase period between 2006 and 2011, the most affected regions are Africa and Southeast Asia; the States or locations most affected are Somalia/Djibouti, the Red Sea/Gulf of Aden, Indonesia, Nigeria, Bangladesh, and Malaysia. The most found types of attacks are "ship boarding" and "attempted boarding," "fired upon," and "knife" attacks. Violence is mainly exerted through "crew taken hostage." The ships affected usually come from Panama, Liberia, Singapore, and the Marshall Islands. The most affected types of ships are bulk carrier, tanker (crude oil), and container.

For the full timeframe, as well as for both piracy increase periods, the figures informed are less relevant for East Asia, America, and the rest of the world and the following types of attacks: "missing ships," "unarmed attacks," "other weapons," "killings," "assault," and "missing."

As a second statement, the facts just presented and explained under the theory of the Copenhagen School prove that:

The security of maritime trade, understood as its independence and functionality, is transgressed by maritime piracy. At the same time, insecurity turned into vulnerability and threats explains the direct relationship with maritime piracy; that is to say, wherever weak armed capacity can be found, maritime piracy will emerge.

Piracy as a threat may be characterized as an objective fact, given the information published by the ICC. It is also possible to state that it is a threat inherent to the military sector, given the response provided by the States and the International System is the coercive action, involving movements and reduction of the threat.

Maritime piracy is high in those regions and locations where most attacks have occurred to the most common ship nationalities, as their identity is clear, the distance is closer, the time is near, the probability and impact are high, and the history is extended. On the contrary, for those regions, locations and nationalities with the lowest maritime piracy records, intensity is low as a threat, being considered only a risk.

If we explain variability from the beginning of the timeframe analyzed, piracy existed almost exclusively in East Asia and Southeast Asia, to later grow during the first increase period as explained by Chalk (2008). Southeast Asia was then the primary destination that later decreased, and Africa had an increase during the second period (between 2006 and 2011), which later went down after armed action, as pointed out by Marin (2011) and Moral (2015).

Regarding vulnerabilities, maritime piracy shows movements, which might be explained by the affected regions', States', or locations' internal insecurity. The most significant movements occur from Southeast Asia to Africa, showing an indirect correlation for the entire period. Other marked differences can be found between America and Africa, which had similar figures, but turned distant later; the same occurred between East Asia and Southeast Asia. In both cases, the latter were the center of high increases in maritime piracy activity. These regions' vulnerability might well explain the reason for the increase and movement of piracy to these places. More research could be done later to analyze those countries' strength through Failed States and Democracy reports.

As for its features as a threat, piracy is heterogeneous, and the best way to describe it is in relation to time and space. A reflection on piracy is that, as a threat, it can be classified as inherent to the military sector due to its coercive agents with no explicit classification of the threatening action; instead, it is an implicit or tacit threat, in which the attack is discrete and without previous demonstration. On the other hand, facts prove that the armed forces are used coercively against private and criminal agents with high coercive power.