I. Introduction

FINDING the best practices in software coding is an important and demanding task, only improving the quality of the code is a tedious process. For example, developers can expend between 35-50% of their time just debugging their code (https://thenewstack.io/the-time-travel-method-of-debugging-software/) which can cost billions of dollars (https://metabob.com/blog-articles/shifting-left.html), many companies prioritize speed or quantity over quality (https://www.knowledgetrain.co.uk/agile/agile-project-management/agile-project-management-course/agile-principles).

The software development process is an intellectual activity, and time is the most important assessment to calculate the cost of a software product. Companies take seriously the time variable in software production; therefore, they are continuously looking for ways to reduce this variable to improve the profits of the organization. Understanding how the debugging process could be improved by reducing the time spent from a scientific perspective is important to help companies to be more productive.

There are a few papers that explain the different proposals in SA. For example, Heckman and Williams [1] present a well-detailed analysis of the identification techniques in SA. Also, Kaur et al. [2] identified different areas of code smell detection using several machine learning and hybrid techniques. The authors show that hybrid approaches present better results in comparison to machine learning. Also, Al-Shaaby et al. [3] wrote a systematic literature review about smell code detection with machine learning techniques. Azeem et al. [4] present a literature review of code smell with machine learning. Akremi [5] provided recent efforts in static analysis tools to classify different false positive outcomes. However, there is a missing paper that shows the evolution of this important topic with its subfields.

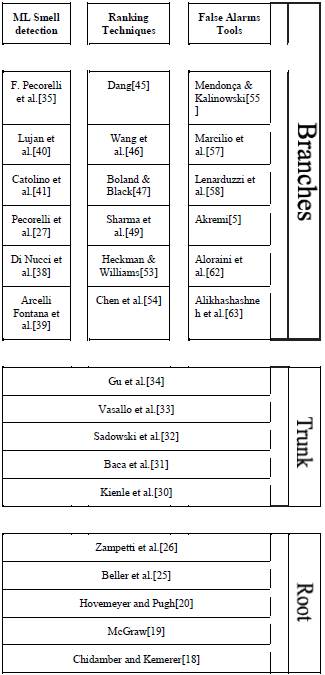

The purpose of this paper is to identify the main contributions of SA in academics. We applied the Tree of Science (ToS) algorithm from a Scopus search to show the evolution of SA from a tree perspective [6]. This paper presents the evolution of SA with a tree metaphor; papers in roots represent the classics, the trunk the structurals, and the branches present the current subfields [7]. The platform to create the ToS of SA was built using R and Shiny apps and Works only with Scopus files (https://coreofscience.shinyapps.io/scientometrics/).

The results show a growing development of SA and show the importance of the subject in academic literature. SA has been transformed since the first proposal and, today, Artificial Intelligence (AI) has become a relevant issue in this field because this technology continues to learn from possible errors and bad practices. This is a cyclical exercise that allows generating a specialized tool to alert when it is incurring a failure, in the future can be the entrance for errors that can be costly to solve after a production start-up or the implementation of processes that depend on a code fragment with sensitive vulnerabilities.

The rest of the paper is split into three parts. The first part presents the methodology of ToS, and the second part shows the main results with a tree metaphor. Finally, we explain the main contributions of SA to academic literature.

II. Methodology

We used the Scopus database to identify the main literature on SA because it is recognized as one of the most important and one of the biggest databases [8]. The words searched were: “static analysis” in the title and “alert or bug or defect or fault or warning” in the title, abstract, and keywords. We had 199 results from the search without filtering by year or document type. Next, the seed (the 199 registers) was uploaded to the shiny application to identify the ToS of our topic. ToS creates a citation network and then applies the SAP algorithm to identify the relevant papers [6], [9]. ToS has been applied to identify relevant literature in management [10]-[12], psychology [13], education [14], health [15], and engineering [16]. The explanation of the ToS diffusion is found in Eggers et al. [17].

III. Results

A. Root

ToS algorithm presents the papers in a tree shape that lets us discover the SA topic's evolution (see Figure 1). The first paper in the roots is the study of Chidamber and Kemerer [18], who implemented six metrics to evaluate software development. Chess and McGraw[19] were more specific in SA, they show how security analysis could be applied in SA. Hovemeyer and Pugh [20] proposed a system to automatically identify bugs that makes this task easier. Heckman [21] identified the bottleneck of the SA programs, they identified many false positives, therefore, she proposed a ranking algorithm to help developers select the most important bugs in their code. Another solution to this problem is proposed by Ruthruff et al. [22], who suggested a logistic regression to identify the most relevant bugs. However, Bessey et al. [23] show the pros and cons of SA software, they have been in the industry for many years and shared their positive and negative experiences. Johnson et al. [24] conducted several interviews with developers and identified the same problems with false positives. Beller et al. [25] presented an analysis of different tools for SA and show that they are widely used and these tools have minor modifications through time. Finally, Zampetti et al. [26] present the benefits of SA tools.

B. Trunk

Documents in the trunk show the evolution of different features of static code analysis. For example, Hallem et al. [27] proposed the metal system to identify bugs in the code. Zheng et al. [28] show that automated static analysis is beneficial for companies. Ayewah et al. [29] show the perception of the effectiveness of FingBugs. Also, Kienle et al. [30] explored how the industry could implement software to automate static analysis. Baca et al. [31] focus their attention on security analysis in a case study. Sadowski et al. [32] highlight the importance of developer workflow integration in static analysis tool adoption. Vasallo et al. [33] proposed that Automatic Static Analysis Tools (ASA) are applied differently depending on the context. Finally, Gu et al. [34] expose the challenge of SA in large projects and proposed BigSpa for this.

C. Branch 1: Machine Learning for Smell Detection

The first branch is code smell detection. Code smells are “symptoms that something may be wrong in software systems that can cause complications in maintaining software quality” [2]. Machine Learning (ML) is the most popular strategy to identify these types of issues. For example, Pecorelli et al. [35] investigate the impact of using ML approaches in code smell detection. They found that balancing techniques are still in their infancy leading to low accuracy outcomes. However, the ML proposals suffer from low accuracy, and comparisons from random models present similar performances [36]. Also, Pecorelli et al. [37] compare the performance of ML models resulting in low values of accuracy. Di Nucci et al. [38] replicated a study with different datasets with more types of smells. Arcelli Fontana et al. [39] tested 16 different ML algorithms and showed that high performances are archived by random forest; also, Lujan et al. [40] found an important increase when they compared several ML tools for code smell. Catolino et al. [41] proposed an intensity index metric based on ML models to identify the severity of a smell code. Also, Pecorelli et al. [42] proposed an ML approach to rank code smells. ML can detect code smells [43]. Das et al. [44] proposed a model to detect two types of smells using a deep learning approach.

D. Branch 2: Actionable Ranking Techniques

The ranking techniques branch is the oldest one in the tree, the newest paper is from 2020 and the next one is from 2013. Even though this branch has 87 papers, it only has 10 papers from the last 10 years.

Static analysis tools show software warnings; however, the results show too many alerts overwhelming the developers. Dang [45] proposed identifying the most relevant warnings in Java and C++. Wang et al. [46] used support vector machines and Naïve Bayes to identify and classify new bugs. Boland & Black [47] proposed Juliet for testing compromising important warnings in C/C++ and Java. Allier et al. [48] proposed a framework of six algorithms for ranking techniques. They show that algorithms based on past alerts perform better than linear regression or Bayesian network techniques. Sharma et al. [49] assessed ML techniques to prioritize bugs in SA and the ML performance was above 70%. Shen et al. [50] presented EFindBugs tool to remove false positives and rank real bugs. EFindBugs is a self-adaptive program that uses the user's feedback to optimize prioritization in Java projects. Liang et al. [51] proposed a training set to identify warnings and automatically label them with 100% of accuracy. Nanda et al. [52] developed Khasiana, an online portal for SA that provides multiple analysis tools for depth analysis, different important warnings, and customized defect reports. Heckman & Williams [53] used ML techniques to classify actionable warnings; they obtain 88-97% accuracy using three to 14 alert features. Chen et al. [54] implemented IntFinder combining static and dynamic analysis providing more accurate bug predictions.

E. Branch 3: Technical alert tools

Mendonça and Mendonça & Kalinowski [55] proposed Pattern-driven maintenance (PDM), a method to create new rules in SA. Serban et al. [56] created SAW-BOT, a bot that proposes fixes for static analysis alerts. Marcilio et al. [57] present SpongeBugs for recommending fixes to developers. Lenarduzzi et al. [58] show the importance of identifying the rules applied in SonarQube because it could reduce fault-proneness. Akremi [5] proposed a categorization of SA techniques to compare different tools. Liu et al. [59] created AVATAR to automate the correctness of bugs, in other words, a patch generator. They showed that AVATAR can fix more than 90% of the bugs. Also, Bavishi et al. [60] created PHOENIX to automatically program repair with high performance. Wyrich & Bogner [61] presented the Refactoring-Bot to remove Java bugs automatically. Aloraini et al. [62] proposed OWASP to automate the detection of vulnerabilities and Alikhashashneh et al. [63] created a new metric to identify errors called F-measure.

IV. Discussions

What are the main reasons to find smelly software?

The maintainability of source code is an ongoing task in the field of software development. As long as there are software solutions that fulfill a task through an algorithm, there will come a time when they become obsolete or prone to bugs. This is where continuous maintenance of the source code comes into play. It involves updating and correcting the code to adhere to best practices and prevent system failures. Developers must stay updated with technological trends to enhance system resilience and minimize future errors.

What contributions can be made from Big Data and ML for error detection?

One significant approach is the application of Machine Learning models for various purposes such as identifying common errors, assessing the severity of poorly written code, classifying code smells, automatically identifying vulnerable code, detecting false positives, and improving the accuracy of error prediction. Moreover, ML-based models can propose corrections to code smells and even automatically correct coding errors. These advancements in the field of statistical analysis of software have led to substantial progress, resulting in significant savings in terms of effort and cost for software companies.

What sophisticated tools are there today that can be kept in mind for the SA?

Several tools and projects are available today to support static analysis of code and offer ML-based analysis models. Examples of such tools and projects include SAW-BOT, SpongeBugs, SonarQube, PHOENIX, EFindBugs, Metabob, GitHub Copilot, AVATAR, and OWASP.

V. Conclusions

This study presents a literature review of SA using the ToS metaphor and presents the results in three sections: roots, trunk, and branches. We identified three main branches of SA: ML for smell detection, ranking techniques, and Technical alert tools. ML is becoming increasingly crucial in smell detection but there are still challenges to increasing the accuracy of the results. The ranking techniques branch was a dynamic subfield but due to the difficulty of identifying important actionable bugs and the emerging new techniques to automate the review process, this branch lost activity in recent years. The third branch presents some tools for detecting bugs, some examples are SAW-BOT, SpongeBugs, and SonarQube. One of the cutting-edge techniques identified is the automatization of correctness bugs; for example, PHOENIX is a program that can fix automatically the bugs in a code, in this vein, the programmer will only need to test the software after the automatic detection.

SA is a dynamic research topic and it has evolved fast during the last years; however, emerging technologies such as Metabob (https://metabob.com/) and GitHub copilot have proposed big changes in the industry. Therefore, AI is positioning the next generation of SA tools and solutions to bugs and future technical debt there will always be technical debt in a software product because the improvements of implementations or updates are a support stage that will always be necessary, from refactoring by new technologies to the implementation of more productive and simple development patterns, for such reasons it reinforces the theory that measuring the passage of time will always require increasingly sophisticated SA tools that allow for a shorter time to consider possible breaches and recommendations to meet new trends and technological needs that require the maintainability and continuous improvement of the software.