Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

CS

versión impresa ISSN 2011-0324

CS no.15 Cali ene./abr. 2015

https://doi.org/10.18046/recs.i15.1963

ARTICLE

The impact of Economic liberalization on Gender equality in Colombia**

El impacto de la apertura económica en la equidad de género en Colombia

O impacto da abertura econômica sobre a igualdade de gênero na Colômbia

DIANA MARCELA MÉNDEZ*

* Bachelor degree in Economics and Major in Finance from Los Andes University. MBA from Icesi University, in cooperation with Julius Maximilians University in Würzburg (Germany). Winner of the scholarship ''Liderazgo por Bogotá 2014'', from the Alberto Lleras Camargo School of Government at Los Andes University. Special interest in economic and social development affairs. She served as Junior Advisor in Social and Economic Cooperation at The Ministry of Defense and as Consultant in Economics and Project Management at Santiago de Cali Mayor's Office. She also has lead relevant projects related to economic development and regional competitiveness. Email: dianamarcelamh@gmail.com

Article submitted 09/03/2015 and accepted 25/04/2015.

ABSTRACT

This paper aims to analyze the impact of the economic liberalization on the performance of gender equality indicators in Colombia. The examination includes multiple dimensions such as access to labor market, schooling, health services and political participation. As a resource it was used the database of the United Nations, as well as the statistics of some Colombian government entities. The results indicate that the opening to foreign markets brought new opportunities for women to participate in the labor market and to improve their educational levels. However, they are still victims of gender disparities, which are manifested in terms of income and employment quality. Women have lower wages than men and are more likely to work in the less productive sectors. Educational level and economic autonomy are strongly correlated with health conditions, domestic violence and women's empowerment. Less educated women have higher fertility and mortality rates, are more vulnerable to domestic violence and continue to have low participation in political parties. Most of the causes of this situation are associated to roles, abilities and skills related to gender. In spite of several policies, there is a considerable necessity of structural changes to fulfill the targets.

Key words: Economic liberalization; employment; gender equality indicators; women

RESUMEN

Esta investigación tiene como objetivo analizar el impacto de la apertura económica en el comportamiento de los indicadores de género en Colombia. Dichos indicadores incluyen múltiples dimensiones, tales como: el acceso al mercado laboral, el nivel de escolaridad, el acceso a los servicios de salud y la participación política. Para cumplir con los objetivos de la investigación se utilizaron las bases de datos de las Naciones Unidas y estadísticas relevantes de algunas entidades del Gobierno Nacional. Los resultados indican que la apertura a nuevos mercados trajo consigo efectos positivos para las mujeres, dado que incrementó sus oportunidades de participar en el mercado laboral y mejorar sus niveles de educación. No obstante, siguen existiendo brechas en relación con el nivel de ingreso y la calidad del empleo al que acceden las mujeres. Un alto porcentaje de ellas reciben menores salarios que los hombres y trabajan en sectores económicos menos productivos, a pesar de que su nivel educativo ha mejorado considerablemente. Se encontró también que el nivel de educación y la autonomía económica de la mujer son factores que influyen en sus condiciones de salud, victimización y nivel de empoderamiento. Las mujeres menos educadas tienen mayor probabilidad de ser víctimas de violencia intrafamiliar y de tener mayores tasas de fertilidad y mortalidad. Así mismo se encontró que las mujeres siguen teniendo baja participación en cargos políticos o posiciones que impliquen la toma de decisiones relevantes. La mayoría de los casos de segregación por género se asocian con los roles, habilidades y características culturales que la sociedad ha atribuido al género femenino. A pesar de que en Colombia se han creado diversas políticas para disminuir la inequidad de género, éstas se han orientado en su mayoría a generar acciones de corto plazo. Se requiere entonces de la adecuada coordinación de las instituciones públicas y privadas, con el fin de realizar cambios estructurales e implementar acciones efectivas que permitan reducir mucho más este sesgo.

Palabras clave: Apertura económica; empleo; indicadores de equidad de género; mujeres

RESUMO

Esta pesquisa tem como objetivo analisar o impacto da abertura econômica no comportamento dos indicadores de gênero na Colômbia. Estes indicadores incluem múltiplas dimensões, como o acesso ao mercado de trabalho, o nível de educação, o acesso aos serviços de saúde e a participação política. Para cumprir com os objetivos da pesquisa, foram utilizados os bancos de dados da Organização das Nações Unidas e estatísticas relevantes de algumas entidades do Governo Nacional. Os resultados indicam que a abertura a novos mercados trouxe efeitos positivos para as mulheres, uma vez que aumentou as suas oportunidades de participar no mercado de trabalho e melhorar os seus níveis de ensino. No entanto, subsistem lacunas em relação ao nível de renda e qualidade de empregos acessíveis às mulheres. Uma alta porcentagem delas recebe salários inferiores aos dos homens e trabalham em setores econômicos menos produtivos, apesar de que seu nível educacional melhorou consideravelmente. Constatou–se também que o nível de educação e a autonomia econômica das mulheres são fatores que influenciam as suas condições de saúde, vitimização e nível de empoderamento. As mulheres menos instruídas têm mais probabilidade de ser vítimas de violência doméstica e ter maiores taxas de fecundidade e mortalidade. Além disso, constatou– se que as mulheres ainda têm baixa participação em cargos políticos ou cargos que envolvem a tomada de decisões relevantes. A maioria dos casos de segregação de gênero estão associados com os papéis, habilidades e características culturais que a sociedade tem atribuído ao sexo feminino. Embora na Colômbia têm–se criado várias políticas para reduzir a desigualdade de gênero, estas estão principalmente orientadas para gerar ações de curto prazo. Portanto, a coordenação adequada das instituições públicas e privadas é necessária, a fim de fazer mudanças estruturais e implementar ações efetivas para reduzir ainda mais esta distorção.

Palavras chave: Abertura econômica; emprego; indicadores de igualdade de gênero; mulheres

Introduction

Nowadays, gender equality plays an important role in the attainment of development goals and poverty reduction. Gender issues are relevant not only because encourage women's protection and guarantee their fundamental rights, but also because they are a general concern. As Amartya Sen (2000) mentioned, gender equality not only affects women's welfare, but it also correlates to the general welfare, because the improvement of women's education and income reduces both the infant mortality rate and fertility rate, improves the maternal health and increases the economic level of the households.

As it is mentioned in the World Bank Development Report (2012), the empowerment of women and the participation in the economic affairs, such as labor market and access to property, have a relevant impact in the economic and social development of the countries. It transcends to the economic area because the mainstreaming of gender equality creates smart economies, which are characterized by efficiency improvements, higher productivity and development outcomes, and more representative institutions for future generations. That is why reducing gender inequalities becomes an important issue, which should be addressed in order to ensure equal rights and opportunities for women and men. It is important that governments, civil society, private sector and the international community assume an active role in the achievement of this goal.

Since its inception in the global political agenda, this topic has become so relevant to the countries, that in 1995, the United Nations (UN) introduced the first global gender indexes: The 'Gender Inequality Index' (GII) and the Gender Empowerment Index (GEM). The promotion of gender equality is also an important concern of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) not only because it is an essential dimension of human development, but because it has a direct relationship with other global targets such as the eradication of hunger, the eradication of HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases; and the achieving of environmental sustainability and universal primary education.

In Colombia, the new liberalization trends have allowed an increase in women's participation in economic, social and political affairs. However, women are still struggling against segregation in the fields of labor market, schooling and health services. They are also more vulnerable to economic crisis and violence. In the last decade, the Colombian Government has made important efforts to improve the measurement of these indicators. However, the addressing of this matters requires not only the intervention of the public sector, but also the cooperation of the private sector and the civil society.

In this research we analyzed the impact of economic liberalization in gender equality in Colombia. It is made by means of examining the performance of gender disparity indexes in Colombia, before and after the adoption of policies concerning the economic liberalization project. The indicators assessed are constituted by a set of dimensions suitable to the measurement of gender equality. Among these indicators, some of the most important are those of access to labor market, schooling, health services, political participation and empowerment.

The analysis was based, on one hand, on data retrieve from the United Nations database, and, on the other hand, on statistics from some Colombian Government entities.

The paper has the following structure: It begins presenting a general review of the economic liberalization trends in Colombia. Secondly, it defines the gender disparity indicators used in the analysis, and explains the methodology of the research. Subsequently it presents the results of the gender indicators performance in Colombia, and the liberalization effects on women's conditions. Next, it presents a discussion, in which there are considered other studies' approaches. Lastly, it is revealed some relevant information regarding the programs and policies committed to promote gender equality in Colombia.

Background

Colombia only had a real insertion in the international market in the twentieth century. This situation was the result of both long years of industrial and agricultural protectionism, and a conservative political leadership that refused to participate in capitalism. The most important step the country did to get into the international trade began in the 90s, and was strengthened by the president Cesar Gaviria (1990–1994). The new model replaced the previous protectionist economy, based on the substitution of imports, for a neoliberal model characterized by massive capital inflows, the expansion of the capital market and the growing of manufacturing and services markets.

The massive capital inflows were the cause of ''speculative bubbles'' and of an excessive rise in credit, and public and private expenditure. In addition, the asset prices increased very fast, and the imbalance of exports and imports generated a deficit in the current account balance of payments; and consequently in the appreciation of the national currency. According to Kalmanovitz (2000), the Central government spending went from 10% of GDP in 1990 to 18.5% in 1999, and the deficit reached 7.7% of GDP that year. Capital inflows also helped to modernize the Colombian industry, leading to excessive investment in traditional sectors such as public services and construction. Both the public and the private sector experimented a substantial increase in their debt.

As a result, the redundancy of internal and external debt put the country in a vulnerable situation, making it more sensitive to changes in interest rates, and to the devaluation of the exchange rate. In fact, in 1998, when the global crisis erupted, Colombia was in an unstable macroeconomic condition. The crisis generated the downfall of the private sector equity and a drop of national income and employment.

Likewise, excessive spending, and a lack of a disciplined fiscal policy, increased Colombia' s state dependence on foreign credit, which caused it to lose losing autonomy concerning its spending policies.

In terms of social investment, there was an increment in public expenditure. This process was intended to improve social indexes, such as secondary education enrollment and health services. Between 1993 and 1997 the population with unsatisfied basic needs decreased from 37.9% to 25.9%. Likewise, the Quality Life index (QLI) improved its performance, as well as the proportion of people in extreme poverty conditions.

Despite the progress, the crisis of 1998 generated a setback, especially in urban population living in extreme poverty and the QLI index. Additionally, the recession affected the labor market, increasing the number of unemployed workers to 1.4 million during the period 1998–1999. In addition, the income gap between workers with university education and those without it reached higher levels, as well as the rural–urban gaps. The advancement in social expenditure began in the 70's, and started to decline in the 80'ss. By the time of the 90's crisis this setback became really profound.

According to the Colombian economists, the causes of the deep crisis are related to the lack of an accurate macroeconomic strategy, as well as the insufficient effects of inaccurate national policies, which were inadequate to the task of managing with the risks resulting from the globalization process. The Nation neither count with the required productive and technological development, nor had the infrastructure required to integrate itself smoothly into the economic liberalization worldwide trend.

Furthermore, social investment was not financed by real income but by means of the expansion of price levels. This policy generated a discontinuous social progressivism. Finally, there was not a control of capital inflows and financial markets in order to prevent speculative bubbles, and the adjustment of the monetary authority affected mainly the private sector, which had a negative influence over employment and domestic demand levels.

Methods

Selection of indexes

There are several indexes of measurement of gender equality, but I based my research in the United Nations' ''Gender Inequality index'', which offers a very complete approach that combines multi–dimensional aspects of gender disparity. This index consider three dimensions: health, empowerment and labor market. Each one of these dimensions is compounded of five indicators, which are Maternal mortality ratio, adolescent fertility rate, females and male population with at least secondary education, females and male shares of parliamentary seats, and female and male labor force participation rates. I used these five indicators, and added another set to them. This set includes unemployment, distribution of employed women by sector, average salaries, and a subset related to domestic and sexual violence. Taking into account that the measurement of gender gaps requires a profound analysis, I considered that the aforementioned additional criteria will allow me to produce key insights, needed to bring forth an accurate understanding of the causes underlying the gaps between women and men.

Gender equality Indexes

GII (Gender Inequality Index): ''captures the loss of achievement due to the gender inequality in three dimensions: reproductive health, empowerment and labor market participation. The higher the GII value, the greater the discrimination'' (Human Development Report, 2013: 31).

GEM (Gender Empowerment Index): ''was introduced as a complementary measure of gender equality in political, economic and decision making power. The three dimensions included are (i) control over economic resources, measured by men and women's earned income; (ii) economic participation and decision making, measured by women and men's share of administrative, professional, managerial, and technical positions; and (iii) political participation and decision making, measured by male and female shares of parliamentary seats''. (Gaye & Klugman, 2010: 4)

Labor force indicators:

Labor force participation rate: it is the proportion of the population which is within, or above the age range of 15 years old, that t is economically active: It refers to individuals supplying labor to the production of goods and services during a specific period.

Contributing family workers: these are the workers who hold ''self–employment jobs'', and present themselves as own account workers within a market–oriented establishment, which is commonly operated by a related person, who is living in the same household.

Wage and salaried workers (employees): these are those workers who hold the type of jobs defined as ''paid employment jobs,'' where the incumbents hold explicit (written or oral) or implicit employment contracts that give them a basic remuneration, which is not directly dependent upon the revenue of the unit for which they work.

Youth unemployment: refers to the share of the labor force between the ages 15–24, which is integrated by persons who have no work but are still available for it, or seeking employment.

Education indicators:

Youth (15–24) literacy rate (%): its total is the number of people between the age of 15 to the age of 24 years who can both read and write, understanding a short simple statement on their everyday life. This total is divided by the population in that age group. Generally, 'literacy' also encompasses 'numeracy', which is the ability to make simple arithmetic calculations.1

Adjusted net enrollment: is the number of pupils of in the school–age group who are enrolled either in primary or secondary education. This number is expressed as a percentage of the total population in that age group.

Health indicators:

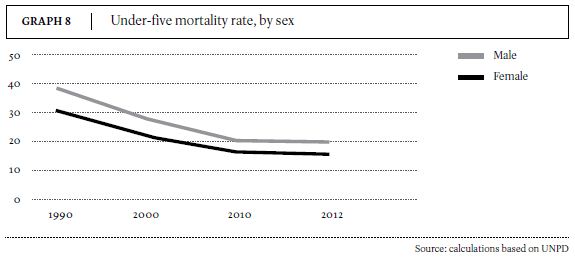

Under–five mortality rate: it is the probability per 1,000 that a newborn baby will die before reaching age five, if subject to current age–specific mortality rates.

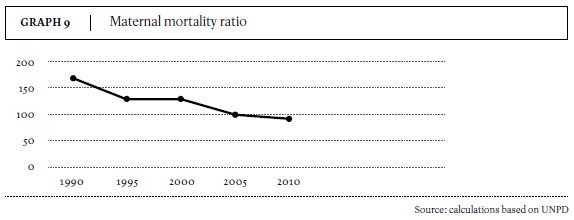

Maternal mortality ratio: is the number of women who die during pregnancy and childbirth, calculated per 100,000 live births. The data are estimated with a regression model, using information on fertility, birth attendants, and HIV prevalence.

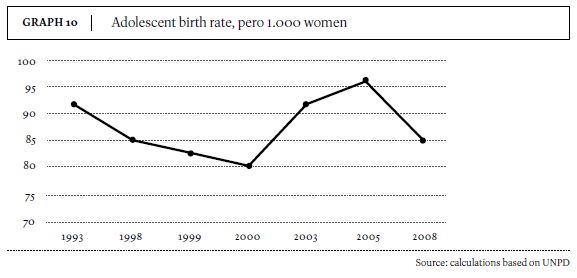

Adolescent fertility rate: is the number of births per 1,000 women between ages 15–19.

Empowerment and political participation index:

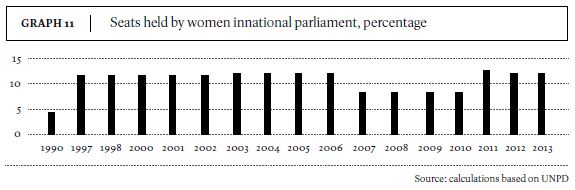

Seats held by women in national parliament: number of seats occupied by women in parliament. This indicates the women's visibility in political leadership and society. Our second indicator is the share of female and male seats in parliament.

Violence indicator:

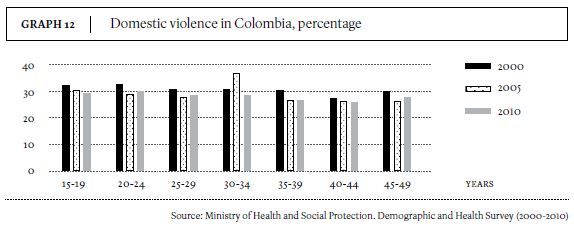

Domestic Violence: this indicator encompasses any incident of threatening behavior, violence or abuse (whether psychological, physical, sexual, financial or emotional), that occurs between adults who are or have been intimate partners or family members, regardless of gender or sexuality.

Data Collection

The data were collected from the UN and the World Bank databases, the colombian Ministry of Health and Social Protection, the colombian Ministry of Education, and the Colombian Statistical Department (DANE). The analysis considered two periods. The first one expands since 1984 until 1990, and the second stretches from 1991 until 2011. This allowed a comparison before and after economic liberalization, whose influences begin to have a greater impact circa 1990, when the Colombian Government decided to open the economy. However, it was difficult to find enough data for the period between 1984 and 1989. It happened because the measurement of gender equality became a relevant concern just around the 90's decade. Hence, the indicators related to gender are relatively new. In addition, there is not enough data to construct Colombia's indicators. At this point, it is important to mention that some of the indicators only show the second period, which began around 1991. So, in order to overcome this scarcity of available data, I tried to collect the most recent year available for each period; and, at the same time, aware of the danger of a bias in the analysis, I strengthened the controls when dealing with the data.

Results– Analysis of the Performance of the Gender Indexes in Colombia

Gender Inequality Index & Gender Empowerment Index

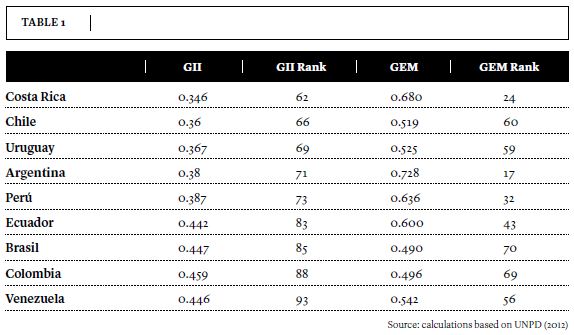

As seen in Table 1, Colombia, with 0.459, ranks 88 among 208 countries included in the list of Gender Inequality Index reported by the UN; and is the number 69, with 0.496, in the ranking of Gender Empowerment Index. Likewise, the country ranks 8 in the list of 9 Latin American countries presented in the analysis. As it is shown, Colombia is one of the most unequal countries in terms of gender segregation and women's empowerment.

Labor force indicators

Labor market studies about Colombia such as the one made by Garcia (2000) have found out that there is a strong correlation between economic growth and employment rates. In fact, this approach has elicited the existence of a positive relationship between those variables. According with the study, the increase of two percentage points in GDP is reflected in the rise of one percentage point in the level of employment. In addition, economic growth and employment have a significant impact in the level of income. In Colombia, the highest levels of employment and salaries have occurred in times of economic surplus.

The economic liberalization came out with new market trends such as the expansion of the capital market, massive capital inflows, and a period of growth in the manufacturing and services markets. New capital inflows supported modernization of the Colombian industry, which in turn led to an expansion of the investment rates in traditional sectors like public services and construction; and also to an increment regarding public and private expenditure.

One of the most important features of this period was the change in the composition of exports. During these years Colombia experimented a decrement concerning the rates of its traditional exports, such as coffee, oil, coal and nickel. These goods were replaced by textiles, food, chemicals, clothing and other non–traditional exports. This economic sector was one of the largest contributors to the GDP growth, which was of 4,3% in 1990, what is a sensible increment when compared with a 3,4% for 1984 (Banrep, 1998). The new model brought up not only economic changes. There were also important transformations in demographics, culture, and the character of the institutions. These changes make way to the entrance of new employees into the labor market, the rise of salaries, and the improvement of household income.

Graph 1 shows the performance of the participation rate by sex for the labor force. As is shown in the graph, the participation of women and men in the labor market increased considerably across years. Labor force participation undergone an important increment between 1989 and 1990. It is important to mention that, since then, women have been improving their contribution in economic issues. Nowadays, they are more integrated into the labor market and perceive higher salaries than before. According to United Nations data, the participation of women in the labor market increased from 38.4% in 1984 to 54.3% in 2012. The increment in the level of education of women has been a key issue underlying these trend.

However, the gaps in labor force participation and income between men and women persist. Although these gaps have become smaller in what concerns the younger population, women still have to overcome several structural barriers to get into the labor market. Recent data show that the labor force participation gap between men and women has a rate of 24%. This situation is related with the difference between paid and unpaid employment. According to the CONPES 1612 women spend 28 hours working in unpaid activities such as housework and childcare, and 40 hours in remunerated activities, whereas men spend 49 hours in paid employment, and only 8 hours in unpaid work. Domestic work is invisible for the labor market, so it limits the possibility of economic independence for women.

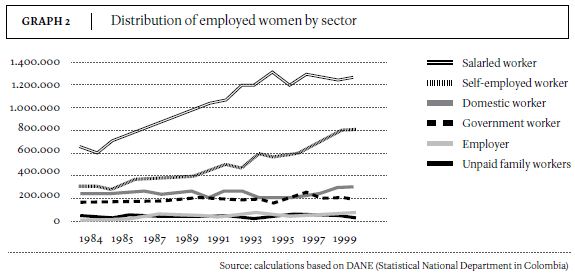

As previously mentioned, there is a positive correlation between economic growth, employment, and levels of income. However, the fluctuations in these variables depend not only on this cause but on other issues like interest rates, and exogenous variables such as taxes, transaction costs, information gaps, technologies, training abilities, etc. Therefore, it cannot be say that the performance of unemployment and salary indicators across time and between genders are just the result of the new economic trends. It can be said that in spite of the increase in labor force participation, women are more likely to work in low productive sectors. Graph 2 provides a clear information about employed women distribution, and specifically, it allows us to identify the high participation of women in the informal economy. According to the results, since 1984 to 1999, the number of salaried and self–employed women increased significantly across time. As it is stated by the National Statistics Department, self–employed workplaces and salaried works are considered as informal sectors, characterized by informality and lower growth rates.

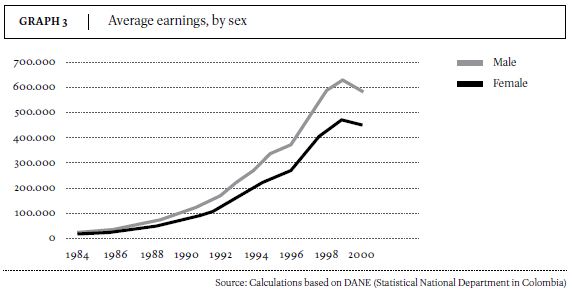

As shown in the Graph 3, across the years women have received less perceived salary than men. Throughout the period that stretches from 1984 to1990, the average earnings between women and men did not show a great disparity. It was until the 90's that this gap became wider. Starting from the decade of the 90's, the colombian labor market has been suffering several transformations. Among them, first of all, is the fact that due to the economic liberalization and the modernization of colombian industry, there was and increment in the demand of more educated workforce, which in turn provoked a rising in the wage gap between educated and less educated workers. It also deteriorated the quality of employment, and transformed the labor contracts, which used to be stable and permanent, to non–permanent, de–regularized ones, thus affecting the stability of labor conditions. In addition, during this period the fields of agriculture, industry and construction experimented a decay that affected mainly and directly the workers with less education. Secondly, the Colombian Government implemented a labor reform in 1990, which increased the percentage of income destined to social contribution, represented by mandatory contributions, such as pensions and health care. This change represented an increment in almost 9 percentage points in the labor cost for employers, which produced an increase of cost recruitment and a drop of wages, competitiveness and employment.

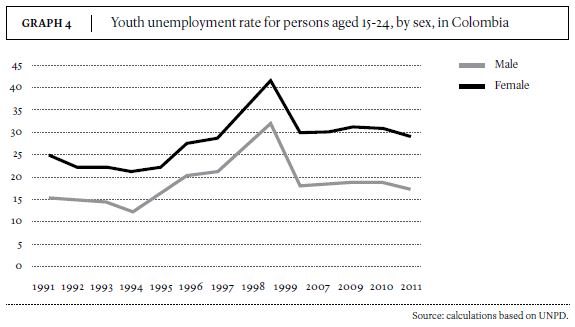

Market fluctuations and changes in labor markets are known to exert a profound impact in vulnerable populations, especially in women. Since women have to deal with gender segregation, they perceive less income and have discontinuous jobs. Graph 4 presents the performance of unemployment index, by sex, for persons aged 15–24. As it is shown in the graph, in 1999, when the highest unemployment rates were achieved, the rate of unemployment for women stood at 41.6%., whereas men had a rate of 32%. Women are more accepted to be economically inactive, so they are prone to inactivity. On the side of demand, there are still gender segregation in labor markets employers have a preference to hire men. This segregation is associated with the skills and abilities related to gender, and to women career choices, which limit the options for them to reach certain positions.

Education Indicators

As it is stated in the World Bank report (2001), education is an individual right and also a way by means of which the individual can get access into the labor market, increase the productivity, and obtain higher incomes. In relation to this matter, the Colombian Human Development Report (2010) indicates that the net enrolment rate of women, between ages 18–24, grew from 21% in 1985 to 27% in 1993. On the other hand, the same rate went from 26% in 1985 to 24% in 1993 in the case of men in the same age group.

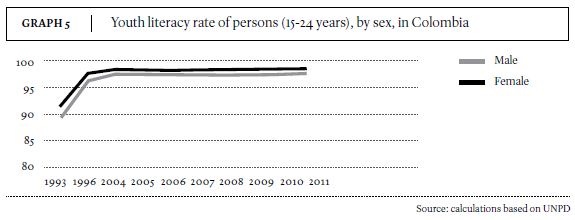

As shown in Graph 5, the decade of the 90's brought about a great progress in the primary and secondary educational coverage, especially for women. The constitutional reform of 1991 presented the Law 115 (General Education Law) which developed a number of strategies in each region, intended to increase the coverage and quality of education. It also offered subsidies to primary and secondary students, and also increased the investment in educational infrastructure. There is not enough information as it would be require to unequivocally establish that higher rates of education are a result of the above mentioned. However, most of the studies regarding to human development in Colombia have found out that earnings and schooling enrolment are highly correlated, especially in the population aged 18 to 24 years.

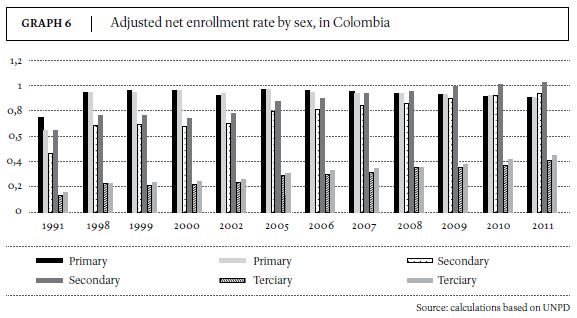

As it is presented in Graph 6, in terms of basic education, many women have improved their indicators, and even have surpassed men. According to Gálvez (2001), one reason for that change is that men are more likely to enter in the labor market at younger ages. On the other hand, the parents educational level appears as correlated with the children educational targets since parents tend to encourage their daughters to improve their economic and schooling conditions.

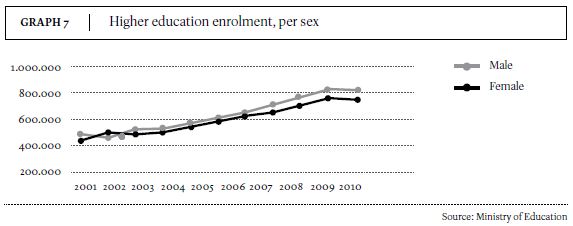

With respect to higher education enrolment, women presented a lower participation when compared to men. In 1985 women participated with 7% and men with 10%, but in 1993 both genders reached the same participation (16%). In the following years women started to present a better performance than men, raising their contribution to 25% in 1997, whereas men contribute with 23%. However, female participation started to decline again in 2002, as it is shown in Graph 7. The number of female students enrolled in higher education was 755.700, whereas men contributed with 818.534. In line with this issue, DANE's Educational Survey (2010) affirms that there is still discrimination concerning the choice of careers and the provision of scholarships. Women participated with 46% of undergraduate scholarships, and 35% of Masters and Ph.D. programs, respectively. There are also differences related to higher education teaching. In 2010, 78.2% of primary teachers were women, but their participation would tend to decrease along the educational cycle. In the case of university levels, women represent only 34.8% of the teachers. The feminization of the first school levels and the prevalence of male teaching in higher education reinforce the gender division of labor in the education sector.

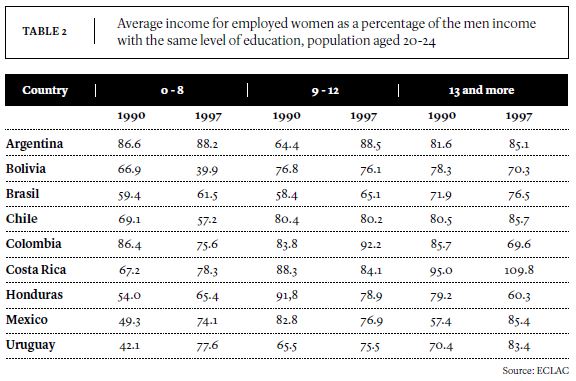

The table 2 presents the average income for employed women as a percentage of the men income with the same level of education. The data shows that in most of the Latin American countries more years of study is related with higher earnings. But, instead of the common Latin–American behavior, Colombia presents an ambiguous performance across years. Although women have better attendance rates and in many cases better educational performance, the magnitude of earnings is not proportional to their level of education, and often they receive lower wages than men, despite they have the same level of education. Some gender entities in Colombia, like Gender Affairs Observatory, have found that most of the causes underlying this situation are related to the social roles that are assigned to women. For instance, women prefer to choose short–period carriers, and as a consequence they are headed up to less paid workplaces. This choice is tied up with the cultural demand on women to fulfill their family role. As a matter of fact, women dropout in school is related to gender roles, which include children caring, pregnancy, and domestic work and so on.

Health Indicators

The data presented in Graph 8 show that women are more likely to find themselves forced to survive under adverse conditions from their early years. One of the reasons for this situation is that the biological advantages of women, make them stronger than men to deal with diseases and conception complications. However, across the year they have to deal with another issues, like social, health and economic segregations, which make them more vulnerable to diseases and mortality rates. There are still important differences between men and women which can be observed in certain concerns, such as maternal mortality rate, adolescence pregnancy, unsafe abortions, nutritional disorders and psychological diseases. These disparities in health service affects more severely the most vulnerable groups, like Afro–Colombians, Native American and rural population.

Regarding unwanted pregnancies and unsafe abortions, the CONPES 161 indicates that in Colombia occurred around 400,000 illegal abortions per year, and about 130,000 women suffer complications due to unsafe abortion. Therefore, abortion complications remain among the leading causes of maternal death. Another issues associated with gender disparity are the cervical and breast cancer, the use of contraceptive methods, and nutritional disorders that are more common in women than men. In Colombia, there are just 46.6% of women between 18 and 69 years reporting specific examinations such as mammographies. In terms of nutritional behavior, women are more likely to suffer of disorders such as anorexia, bulimia and obesity. In 2005, women had twice the rate prevalence for obesity (16.6%) than men (8.8%).

Gender inequalities are strongly correlated with the level of income and education of women, as reported by Sen (2000). In line with this author's approach, education and employment are key factors that have to be addressed in order to reduce fertility rates. On one hand, young unemployed and less educated women have more difficulties controlling their fertility, as well as claiming control over their sexual and reproductive rights. On the other hand, education allows women to be more independent, and to take their own decision in terms of maternity and fertility issues. Furthermore, higher levels of education in women encourage them to think about their own projects and interests, and offer them new opportunities to participate in the market. Since education increase the opportunities to get access into labor markets, women who have income autonomy reduce their vulnerability to health risks as long as they can afford better security and social benefits.

As shown in the Graph 11, specific fertility rates for women into the age range between 15 and 19 years have been declining across years. However, there is an abrupt jump between 2002 and 2005, which can be a consequence of the economic crisis effects. As we have seen these impacts are more likely to affect women conditions

Political participation

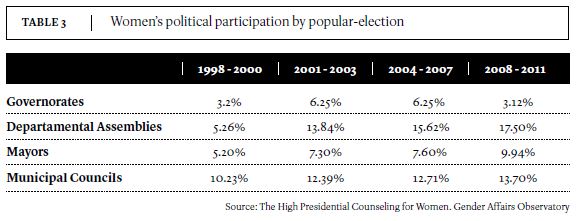

According to The Centre of Gender Affairs of the High Presidential Counseling Office for Women, Colombia presents a partial fulfillment of the women inclusion legislation.3 As shown in Table 3, women positions of power and decision–making have increased across years, but effective political integration remains an issue that have to be addressed, particularly in relation to popular–election offices. Because of a legislation known as the Law on Quotas, women must held at least the 30% of the power public positions. However, recent data reveals that some colombian regions are not fulfilling the goal. On the Governorates side, 8 of the regions recorded percentages under 30%, and 3 of them did not report any data in 2010. Regarding the mayor's reports in 2010, 5 of the cities had percentages under 30%, and 2 of the mayors did not report data.

Female participation in the Congress has remained significantly scarce in the last 4 periods, even in the last period, in which it increased. Indeed, by the 2010 – 2014 elections the percentage of women in the Senate increased 4 percentage points compared with the last election, with a composition of 16%. On the other hand, by reaching 12%, women gained two percentage points in the House of Representatives.

Despite this increment, during the past 13 years, women participation in congress has not exceeded a 12% average of all seats. That situation places Colombia in the last positions in terms of latin–american female's representation in congress. As reported by the ECLAC (2001) and the Gender Equality Observatory of Latin America and the Caribbean, Colombia is in the 23th place among 36 Latin–American countries.

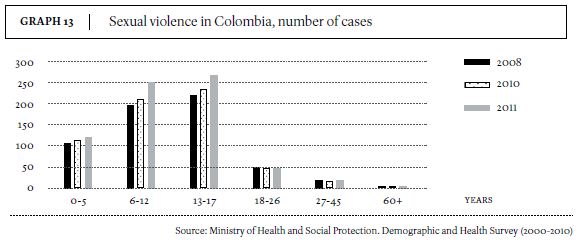

Violence indicators

Colombia has made significant progress in the recognition of violence against women as a violation of human rights, and as a social problem that must be addressed using a multi–perspective approach. However, the phenomenon remains a threat for women, and a serious public health issue. According to the CONPES 161, between 2007 and 2011 Colombia presented 262.581 cases of domestic violence caused by a partner, of which women comprised 88.8% of the cases. In terms of sexual violence, women held 84.1% of the cases; and concerning to psychological violence, 65% of the reports were presented by women who alleged to be victims of their own partner. Unfortunately, just 38% of the cases related to violence against women are reported to the authorities; and 90% of them still go unpunished.

As shown in Graph 14, between 2000 and 2010, intimate partner violence rates, concerning the range of age between 20 to 24 years, experimented a decline from 32.6% to 29.6%. In the range of age between 40 to 44 years, it was also a decline in the percentage of reported cases, which went from 27.1% to 25.8%.

Only for women between 30 and 34 years old, the percentage recorded in the survey of 2005 was much higher than both 2000 and 2010. The rate held 36.7%, which is the highest one recorded for this indicator in all the three surveys. The Ministry of Health have reported that this rate declined 11.37 points between 2010 and 2011 for women between 27 and 45 years old.

For ages 6–12 and 18–26 the rate remained the same from year to year (2010 to 2011). Regarding the sexual violence cases (Graph 13), between 2010 and 2011 the rates showed an increment for women aged 0 to 17, and for those among the ages of 27 to 45 years old. The group of women aged 6 –12 years old presented the most important increment, with a rise of 38 points from 2010 to 2011. At the age of 0–5 years, and 60 and more, the rates remained the same as 2010. It can be seen that the most vulnerable groups are between 6 and 17 years old.

According to the ''National observatory of violence against Women'', this kind of violence is directly related to their lack of economic autonomy. In many cases the fact that they have no access to their own assets, and have rely on men for support, puts women in a vulnerable situation, within which submission is a common response to male violence. Economic empowerment and closure of labor gaps between men and women are essential goals to be attained if Colombia is going to ensure that women have sufficient independence to have a life free of violence. Another relevant issue to have in mind is that women are still ignorant about their own rights and the protection laws concerning their regulation.

Discussion

As well as the study of Gálvez (2001) this research found out that most of the factors related to gender disparity between men and women in the labor market are correlated with gender roles, which are strongly held within the family structure; and also to women 's education level. Since women spend more hours in domestic work than men, they are more likely to work in ''flexible'' employment. However, low–productivity sectors produce lower incomes and pay deficient wages. This situation is also reflected through the fact that women, as employees, have less labor benefits and stability. Although the gap in terms of wages and labor opportunities between men and women has diminished across years, women seem to be more vulnerable to economic fluctuations, and they have to deal with more changes related to employment, quality of jobs and wages.

As stated in the ECLAC gender report (2001), these differences are caused by issues that stem from both supply and demand sides. Female supply is likely to be more elastic than male supply. It happens because cultural roles make women more likely than men to be unemployed. On the other hand, employers usually associate certain skills and abilities with gender, which makes it more difficult for women to reach decision–making positions. In terms of labor market, the study of Galvis (2010) found that there is still an income disparity between women and men, even though women have increased their participation in labor market. According to data results, these gaps seem to be wider in groups with lower wages. However, this study states that gender segregation is not necessarily the only cause underlying the wage gaps. There are other facts concerned to individual issues such as abilities, the quality of education, the motivations that drive women up in their search after a job.

Regarding the access to health services, there are some studies in Colombia, like the one of Herreño and Guarnizo (2008), which shows that women have more needs related to health services. This is due to their vulnerable conditions and higher morbidity. However, they consume 28% of their income in finance health, whereas men spend 25%. Likewise, the possibility that an insurer entity acts as a funding source for health services is higher for men (75%) than for women (72%). These particular insights support the statement that women's disadvantages in terms of working conditions are reflected in a poor quality access to health services.

Political and legal framework in Colombia

In this section I share and discuss the government actions in order to attempt gender equality in Colombia. Public policies regarding the women empowerment in Colombia started in 1984, with the Rural Women Policy, presented by the CONPES 2109. After that, the National Constitution of 1991 reinforced the principles of equity and non–discrimination against women, and the commitment of the State to the promotion of conditions for vulnerable groups.4

In the last three decades national governments have implemented several policies in terms of women empowerment. Among them, several of the most relevant ones are:

Integral Women's Policy (1992)

Participation and equality women's policy (1994)

Plan of equal opportunities (1999)

Women as peace creators policy (2003)

There are also different entities responsible for gender parity across the government, such as Counseling for women, youth and family (1990–1994), Department of women's equality (1994–1998), and Presidential counseling for women (1998–2010). In September of 2010, the president Juan Manuel Santos ratified, by the decree 3445, the Presidential counseling. This entity was renamed as ''The High Presidential Counseling for Women'', and it has the function of supporting the government in what concerns the design of public policies intended to the promotion of gender equality. In addition, it has the mission of monitoring the impact of the national programs related to gender; and that of encouraging the partnerships between the private sector, public sector, ONG's, international entities and Universities which serve that same purpose. Last but not least, it has the responsibility of assisting the national women's organizations, which it does by means of reinforcing the participation of these organizations into national programs.

Regarding this matter, the Colombian Government includes the gender equality into the ''National Development Plan – Prosperity for everyone'' (2010–2014), as a mainstream approach that is addressed throughout a set of public programs and projects. Furthermore, the government has expressed its will to create a national public policy of gender equality. This policy would guarantee women's rights, especially in what pertains the situation of vulnerable social groups such as afro–colombians, native americans and rural population.

In spite of all the efforts and the several policies that have already been created to address the issues that have been examined throughout this paper, gender disparity is still a key issue that has not been overcome. There persist important gaps between women and men in terms of income earnings and political participation. The participation in the most productive sectors is superior for men. Women keep being victims of violence, and they still have to deal with disparities in health services and education.

This lack of performance effectiveness is caused by different aspects. First of all, the development of the state entities in terms of gender issues is not the same in all the cases. For instance, just 5 of the 32 national states have a women affairs office. Secondly, the coordination mechanisms between national, regional and local institutions are fragile, which makes it extremely difficult to pursue the gender goals. In addition, Colombia is a country with an eminently patriarchal culture, and as a matter of fact most of the gender inequalities are derived by the models, stereotypes and roles assigned to both genders by society.

Considering the above mentioned difficulties to the implementation of programs, the National Public Policy of Gender Equality pursues the application of fitting strategies to reduce the Gender disparity. The addressing of this issue must be a long term process which must be driven up under the implementation of measurable results. As a result of this landscape, the CONPES 161, which was held on March 12 of the year 2013, documented the new policy, established according to the guidelines of the National Development Plan.

National Public Policy of Gender Equality

This policy is aimed at the assistance of colombian women from all social groups. It takes into account their cultural, sexual and racial diversity, and focus especially on those women who are in vulnerable or disability conditions. This policy has a 10–year time horizon, and it is intended to assure rights, equality and non–discrimination to women. In addition, this approach look for developing women's skills and the attainment of their life projects.

Strategies

Peace promotion and cultural transformation

In Colombia, women are still victims of violence at different levels, in the private and public sectors, and even more inside the family. Furthermore, some of them who participate in politics, have to deal with the violence provoked by the war conflict inside the country.

It is relevant to address this matter. It could be made by means of transforming cultural patterns. Indeed, it is important to socially attain a recognition of women as important participants in income production and development. In addition, the Government must deepen its commitment with the coordination and monitoring of the gender programs and their performance at national and regional levels. Last but not least, it is relevant to encourage the participation of women in decision making and public policy related with the addressing of the matters that negatively affect their life. The media must be aligned with the process, spreading the information about women rights and gender programs.

Self–reliance, income autonomy and access to assessments

Poverty incidence continue to be higher to women than to men. Even though women have gained some ground within the labor market, they are more likely to work in low productive sectors, and there are still labor constraints and income gaps between men and women. As a matter of fact, most of the women are contributing family workers, but they do not have access to financial security or social benefits.

In order to pursue gender equality in the labor market, the Colombian Government created the law 1496, which was presented in 2011. In accordance with that law, men and women must have equal wage conditions. In the meantime, the Decree 4463, which was presented that same year, proposed the creation of an equality labor program that promotes employment and decent jobs for women. This program has been adopted by the Ministry of Labor, which is the responsible of the application of the mandate.

Regarding the aforementioned, the recognition of the women contribution to the national income and economic development is a key issue that have still not been wholly addressed by the Colombian Government. It is important not only to create new opportunities in the regular sectors, but also in the most productive sectors, such as mineral resources and energy, housing market, infrastructure, agricultural sector and productive innovation areas. Policy instruments have the duty to confront labor risk, especially for those women who work in the agricultural sector. It's also fundamental to guarantee equal access to assets such as land, property, financial instruments and technical assistance, particularly in rural areas.

Empowerment and political participation

Discrimination is still one of the most characteristic features in the field of Women's decision–making. In what concerns political and power management, and specifically policymaking, Women continue to be denied opportunities of egalitarian participation. Between 2010 and 2014, the average share of women in the Senate was of 16%, and at the House of Representatives was of 12% (CONPES 161, 2013).

The Law on Quotas (581) which was presented in 2000, stipulates that women must have at least 30% of average share in public offices at decision–making levels. However, the number of women members in parties has not improve as it was expected. As a result of this state of the affairs it is relevant to encourage the participation of women in decision making and public policy. This target should be achieved in the medium term, by means of searching the attainment of a progressive increment in gender equality across the years. In the same way, it is necessary to strengthen the control mechanisms in a way that would make feasible to enhance women's participation and empowerment.

Access to high – quality health care

Nowadays, Colombia presents health gaps in such dimensions as maternal mortality rate, abortions, mental diseases and nutritional disorders. The Colombian Health Service is concerned about improving the information systems in order to build epidemiology profiles of the national population. Improving data recollection and monitoring processes would allowed the government to identify social patterns in terms of gender diseases. Similarly, is required to prevent adolescent pregnancy by improving the sexual concealing and contraceptive methods, and also to offer better health services to reduce the breast and cervical cancer mortality rates.

High – quality education with gender perspectives

In spite of the improvement of women's enrolment in primary and secondary education, the gender discrimination is still an issue in higher levels. Women's enrolment in Masters and Ph.D. degrees is still lower than men enrolment. In addition, women are more likely to drop out from school for reasons related to gender roles, such as pregnancy, household work, or children caring.

Ensuring enrollment and school attendance for women is an important concern. It is relevant to include the transformation of social patterns and roles based in discrimination and violence against women in the process. In the same way, teachers must use an inclusive language, and attempt to stimulate the participation for both men and women in all knowledge areas. Finally, policymakers must guarantee equality of educational opportunities for women in higher levels, especially for the most vulnerable population such as afro–colombians, native american women and rural population.

Women free from violence

In terms of domestic violence, Colombia presents 1415 cases of women who were victims of homicide. Surprisingly, the 9.5% of these violent actions comes from their own partner or other relative. In 2011 there were 89.807 cases of domestic violence and 82.894 cases of sexual violence. Some studies have pointed out that unfortunately only 38% of the cases are reported to the authorities. Neither currently information systems violence recording against women are not integrated nor are there disciplinary sanctions for public servants who do not regard appropriately the rights of women according to the law. However, the health national sector is making advances in data collection related to sexual and domestic violence. Currently, Colombia has the National Public Health Surveillance of Violence against Women.

Progress is needed in this regard, in a way that should guarantee the applicability of the law and ensure the incorporation of gender approach in the actions of public servants. Likewise, other types of violence which have not been documented so far have to be addressed by the law, including economic violence, human trafficking and violence against the most vulnerable groups.

Projects, programs and results

According to the monitoring reports, between 2000 and 2009, the Government applied certain programs in order to address gender disparities in economic reliance and education, seeking to eradicate violence against women. One of them was the delivery of 30.888 microcredits for households with a female head, as well as training programs for female entrepreneurs. In addition, the Government supported 750 sessions of women's education about their rights and the importance of reporting violence cases. There were also workshops and community meetings, established to discuss issues related to education, health and justice. It was also established a Gender Affairs Observatory which mission is to monitor the development and performance of national policies related to gender issues.

However, during the last five years the progress has been trivial in terms of the agenda designed by the National Public Policy of Gender Equality. Government actions have been focused in the creation of a legal framework. However, in the last five years the progress, concerning the application of the action plan, is essentially inappreciable. Most of the measures do not go beyond the formulation stage. So, this policy can be considered as an inefficient and unarticulated model.

Despite these institutional efforts, the situation of violence against women in the country has not been significantly curtailed by means of the application of different rules and policies adopted by the State. As a matter of fact, this situation continues to be an important concern, since there is a constant increase of these rates in the last three years. Regarding the measurement of the progress in labor participation, the reports presented by the Ministry of Labor do not show a significant progress.

In other words, the official entities which are responsible for gender affairs are not applying adequate mechanisms to address gender disparity. Most of the actions are oriented to develop awareness–raising programs, and those are complemented with studies which are lacking of a clear reference that would drive the pass from the formulation to the action and enforcement of the laws concerning gender equality. Others, such as record creation have a better performance, but their development is not clear, and there are not concrete steps taken to fulfill them.

Conclusions

Summarizing what have been discussed up to this point, gender equality plays an important role, not only regarding human development, but also in relation with economic growth and poverty reduction. Gender equality improves productivity and creates more democratic and efficient institutions.

In Colombia, economic liberalization came about along with the rise of income and the improvement of a limited set of social indexes, especially for women. The new market trends brought up to women new opportunities of both getting access into the labor market and improve their educational levels. However, when the crisis came about they were most affected than men.

Even though gender indicators have improved across the years, women are still victims of gender segregation at the labor market and at the education system. They are more likely to participate in informal employment, and to be forced to work within the less productive sectors. As a consequence, they get lower wages and are more vulnerable to the negative effects of the changes in the labor market and to economic crises. In fact, women are less paid than men, even if they have the same level of education. Likewise, the economic autonomy and the schooling level are strongly correlated with health conditions and violence against women. Women less educated have higher fertility and mortality rates, and suffer under conditions that enhance the possibility for them of being victims of domestic violence. In addition, women continue to be denied opportunities to participate in and political parties.

In spite of the aforementioned, the Government has made important efforts to achieve gender equality. But most of these actions are oriented to short–term solutions such as subsidies and housing benefits, and have not provoked profound changes in the social, economic and educational structures, nor have driven up accurate and suited solutions to diminish the gender gap. There is a considerable necessity for an articulation of diverse institutions; and for a shift in the functioning of the responsible entities, one of such a nature that could allow them to accomplish their duties concerning gender equality.

This research experience brought me many lessons that I deem enough relevant as to be shared through the academic spaces within which the issue of gender equality is being discussed nowadays. First of all, I found out a strong correlation between gender roles and the performance of the indicators. For instance, cultural patterns have a strong impact on women's decisions in terms of choosing their life plan. This fact is changing across the years, especially in the young population. However, women still have to deal with social pressures, such as the demand that pounds upon them to fulfill family roles and spent many hours in housework. Even though the disparity between man and women continues to be an issue to be addressed, it's good to know that the gap is getting smaller across the years, and that there are special entities in charge of pursuing gender equality in all the dimensions that are being studied through different approaches and from different social sciences. I consider that there are other fields which need to be explored and that be encompassed by further research. Among them, one subject of very special interest is the difference between the performances of these indexes' across colombian regions. Another question that has to be explored is the phenomena of violence against women, which is not only a social problem but a public health issue. Regarding domestic and sexual violence I consider very strange the fact that these phenomena do not present a regular pattern but have an irregular behavior through the years and among groups. Some groups seem to be more vulnerable to these forms of violence than other ones, but apparently the causes underlying this irregularity are not as clear as to may be figured out for most cases with relation to which they appear. More researches dealing with these areas would allow us to grasp better insights and find new answers.

NOTES

** This paper is the result of an independent research project, developed and presented in Julius–Maximilians University in Wuerzburgo (Germany, between march and june 2014).

1. Catalog Sources World Development Indicators: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.ADT.1524.LT.ZS

2. ''Consejo Nacional de Política Económica y Social''. The National Council of Economic and social affairs is in charge of advising the Colombian Government in the development of national policies regarding economic and social issues.

3. ''Law 581 (2000) – Law on Quotas'': Stipulates that women must occupy 30% of all public positions at decision–making levels.

4. Articles: 7,13,47.

References

CIFUENTES, L. & RUEDA, M. (2013). II Informe de seguimiento a la implementación de la Ley 1257 de 2008. Bogotá, Colombia: Ediciones Antropos. [ Links ]

DE LA CRUZ, C. (2007). Género, derechos y desarrollo humano. Proyecto America Latina genera PNUD. San Salvador, El Salvador. [ Links ]

FORERO, L. (2012). Indicadores de género en Colombia. Observatorio asuntos de género. Boletín No. 15, 7–15. [ Links ]

GÁLVEZ, T. (2001). Aspectos económicos de la equidad de género. Santiago de Chile, Chile: Naciones Unidas– CEPAL. [ Links ]

GALVIS, L. (2010). Diferencias salariales por género y región en Colombia: una aproximación con regresión por cuantiles. Banco de la República. Cartagena, Colombia. [ Links ]

GARCIA, O. & URDINOLA, P. (2000). Una Mirada al mercado laboral colombiano. Departamento Nacional de Planeación. Bogotá, Colombia. [ Links ]

GAYE, A. & KLUGMAN J. (2010). Measuring key disparities in human development: The Gender Inequality Index. United Nations. [ Links ]

GUARNIZO, C. & HERREÑO C. (2008). Equidad de género en el acceso a los servicios de salud en Colombia. Revista de salud pública, (10), 44–57. [ Links ]

KALMANOVITZ, S. (2000). Oportunidades y riesgos de la Globalización en Colombia. Banco de la Republica. Bogotá, Colombia. [ Links ]

NAJAR, A. (2006). ''Apertura económica en Colombia y el Sector Externo 1990–2004''.Tesis Maestría. Universidad Nacional de Colombia. [ Links ]

OCAMPO, J. Un futuro económico para Colombia. [ Links ]

SEN, A. (2000). La agencia de las mujeres y el cambio social. Desarrollo y Libertad (pp. 233–249). Bogotá, Colombia: Planeta Colombiana S.A. [ Links ]

VASQUEZ, M. & OLARTE T. (2010). Informe de Gestión 2002–2010. Observatorio de asuntos de género. Boletín Edición Especial, 6–32. [ Links ]

Statistical references

ALTA CONSEJERÍA PRESIDENCIAL PARA LA EQUIDAD DE LA MUJER (2012). Lineamientos de la política pública Nacional de Equidad de Género para las Mujeres. Bogotá, Colombia. [ Links ]

BANCO DE LA REPÚBLICA. Banco Central de Colombia. http://www.banrep.gov.co/pibbase–1975 [ Links ]

CONPES 161. (2013). Women's Gender Equality [ Links ]

DANE. www.dane.gov.co/files/investigaciones/boletines/educacion/bol_EDUC_2012.pdf [ Links ]

GENDER STATISTICS UNPD: http://genderstats.org/Browse–by–Countries/Country– Dashboard?ctry=170 [ Links ]

NATIONAL OBSERVATORY OF VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN (2011). Ministry of Health [ Links ]

PNUD (2000). Informe de Desarrollo Humano para Colombia. [ Links ]

THE WORLD ECONOMIC FORUM (2013). The Global Gender Report. [ Links ]

UNITED NATIONS. Human Development Report (2013). [ Links ]

UNITED NATIONS (2013). The Millennium Development Goals Report. [ Links ]