“Mulheres, água e energia não são mercadorias!”1 assert members of the Brazilian popular social movement Movimento dos Atingidos por Barragens (MAB or Movement of People Affected by Dams). Dispossession of people, degradation of land, lack of access to clean water and the efforts to privatize it-these are anthropogenic processes, resultant of a political and economic system. These processes are not inevitable, however, and social movements are engaged in efforts to challenge economistic thinking that privatizes nature and culture (Goldman, 1998). During my early dissertation fieldwork during the Summer of 2018, I became interested in how militantes of MAB framed their efforts as a fight against intersecting systems of oppression.

MAB’s struggle is not just for those directly affected by dam projects or for the right to water; it is a part of a larger “alter-globalization” fight to construct a different world. Social movements are not just actors but producers of knowledge. This assertion is not new. Numerous scholars have examined social movements as critical sites for the construction of knowledge (Conway, 2006; Melucci, 1996; Rivera-Cusicanqui; Aillón-Soria, 2015; Zibechi, 2017). Yet, as Carolina Alonso Bejarano and her coauthors write (2019: 136), despite decades of critique and introspection, social science remains “deeply colonial, embodying, benefiting from, and contributing to the maintenance of Western imperial power”. A “paradigm shift” is needed in how we study movements (Conway, 2017). This point aligns with the argument that sociologists ought to focus more on their own positionality in the world and also acknowledge the problem of methodological nationalism (Conway, 2017; Dalsheim, 2017; Escobar, 2008; Markoff, 2003; Mohanty, 2003; Santos, 2004; Smith, 2017; Vieira, 2015). As Arturo Escobar (2008: 4) argues, “Whose knowledge counts? And what does this have to do with place, culture, and power?”.

I explore the following in this paper: What can academia learn from social movements? In turn, how do scholars produce research that does not reinforce power hierarchies? How do we create collaborative research? And how do these questions speak to the larger area of knowledge production? MAB is an example of the “social thought of the periphery,” which Raewyn Connell (2007: 380) argues that sociologists fail to examine sufficiently. How do we, as Connell (2007: 383) proposes, build a “new language for theorizing?”. For this particular paper, my focus is not specifically on the co-production of knowledge between movements and scholars, but on what academia can learn from movements themselves, who in many cases (including MAB) are producing and publishing theory and research. Due to political uncertainty in Brazil at the time of writing, the decision was made not to use individuals’ names, which was supported by MAB. This is discussed further in the section on data and methods.

Background

Knowledge and Power

The phrase “knowledge is power” is well-known. During my own time working as a community organizer, however, this phrase became increasingly troubling for me. The point was made by many with whom I worked that knowledge does not equal power; that power is a) organized money or b) a large number of organized people; and that power is, simply put, the ability to help or to hurt. The counterargument might be: “But knowledge is necessary in order to build people-power!” Over time, I became less insistent, and accepted that knowledge might not be power. Everything I did was built around the idea of turning out thousands ofpeople to a large annual public action; and I do believe that organized “people-power” might be our best hope of changing this broken world. But if knowledge is not power, then why work in academia? The relationship between knowledge and power is dialectical, and as sociologists (or academics in general), it is imperative that we wrestle with these questions.

Academics strive to pursue “objective” and “sound research.” I am not suggesting that activist academics jettison rigorous and clear methodological strategies. Indeed, the goal of this work is to produce conscientious research and theory. However, to borrow from the field of political ecology, the idea that the knowledge which scholars produce can even plausibly be apolitical is inherently political in itself as “it holds implications for the distribution and control of resources” (Robbins, 2012: 18). Political ecology sees that human culture-with its political and economic constructs which produce and reproduce systems of knowledge, power, and values-must be included in the understanding and study of environment and ecology. I extend this argument to say that the idea of an “apolitical sociology” holds similar repercussions. There is a need for “ethical epistemology”- knowledge production must be derived with and from the community (Watkins, 2018: 43). There is a need for “intellectual activism” in scholarship (Collins, 2013).

Theories are useful as analytical concepts to help understand reality. Yet, when theories are used to exclude or supplant lived experiences-discourses of people on the peripheries- we replicate the very power structures that we seek to dismantle. Abstraction then becomes a vehicle to deny the bloody, colonialist, destructive histories that have formed our world and created the current global capitalist system (Krishna, 2006: 90-92). While colonialism is no longer an economic policy, its legacy remains (Conway, 2017; Escobar, 2008; Krishna, 2006; Mohanty, 2003; Smith, 2008: 44-45). As Boaventura de Sousa Santos (2004) contends, global capitalism has been made possible (and legitimized) by using “modern science” as justification that the ideology and policies produced by it are rational and sound. This has led to the destruction of knowledge or, as Santos refers to it, “epistemicide.”

While it is important to be aware of the destruction of knowledge, it is critical to recognize the many powerful examples of resistance and resilience. If we look to the current discourses of social movements, for example, we see an alternative to the present. This resistance-and articulation of “alter-globalizations” (Bakker, 2007)-is what I seek to discuss here. Alter-globalization (also referred to as counter-hegemonic globalization or globalization from below) is the idea of constructing a world where there is global cooperation and interaction, guided by ideas of human rights, labor rights, environmental rights, cultural and natural sovereignty. It symbolizes the grassroots movements that fight against oppressive structures such as capitalism, colonialism, and patriarchy (Falk, 1993; Santos, 2015). One example of alter-globalization today is found in MAB’s resistance to the privatization of water and energy and its articulation of what could be: the spaces that, as Santos (2004) argues, serve as the “sociology of emergences” where contemporary social movements engage with each other and illustrate alternatives to capitalist social relations.

Knowledge and power are related, and too often, sociology fails to incorporate voices-knowledge-from the periphery. The sociology of knowledge matters because it is linked to perspective; ideas do not emerge from nowhere. Raewyn Connell speaks of Derrida’s notion of “erasure” and how the term means an overwriting, rather than obliteration, of experiences. As Connell (2007: 368) states, “where” matters because “where” is related to voice, experience, and perspective. Connell (2007: 378) argues that while many sociological theories and texts are openly critical of neoliberal globalization, they do “not challenge the way that knowledge of the social is constituted”. This is in large part due to the reality, Connell (2007: 379) asserts, that literature “almost never cites non-metropolitan thinkers and almost never builds on social theory formulated outside the metropole”.

To understand and perhaps ameliorate the various global crises faced by humanity at the present moment-including the unfolding turmoil of viewing water as a commodity rather than a human right- it is imperative to consider Connell’s (2007: 383) call for a “new language for theorizing” to jettison imperialist and colonialist thought. This means engaging with and learning from movements on the ground-or “social thought from the periphery” (Connell, 2007).

Power matters. This is illustrated by Krishna’s (2006) selection of the term “discourse” in the place of “theory”-the former connotes the power relationships at play in a way that the latter does not. In addition to power, discourse forces attention to praxis-what people in counter-hegemonic movements are actually doing. While an important and significant component of activist research must include the co-production of knowledge between scholars and social movements, another critical aspect is for scholars (especially those in the North) to pay attention to and learn from what movements are already producing. MAB (and the various other social movements with whom they partner) would be an example of a discourse-one that too often is, to return to Connell (2007), overwritten (though not obliterated).

Background on MAB

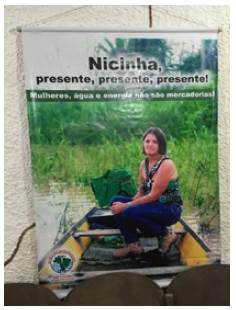

Movimento dos Atingidos por Barragens was formally founded under the name MAB in 1991 as a national movement for the rights of people affected by dam projects. The movement coalesced out of existing struggles (beginning in the 1980s) located in proximity to Brazilian dams. Comprised of communities directly affected by these projects2, MAB leads the fight against the removal of families from their homes and opposes the privatization of water, rivers, and natural resources-resources upon which the communities depend for their livelihood. The movement seeks to not just resist current energy policy, but to articulate alternatives (Hess, 2018; Klein, 2015; see Appendix A, Image 1).

MAB refers to its work as a “popular project.” Their efforts, formalized in November 1999 in Minas Gerais, are committed to “fight against the neoliberal capitalist model and for a new Popular Project for Brazil which includes a new energy model” (Movimento dos Atingidos por Barragens [MAB], 2011). Their motto is “water and energy are not commodities.” In Brazil the two cannot be separated. MAB argues that the povo (people) should have sovereignty and control over their resources and that they should not be for private gain. MAB is also a member of La Via Campesina (LVC) (which I discuss later) and frequently participates in actions with the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (MST), Movimento dos Pequenos Agricultores (MPA)-both of which are also members of LVC- as well as with various other social movements, unions, and human rights organizations (Plataforma Operária e Camponesa da Energia, 2014, and fieldnotes, Summer 2018).

Background on my interest in the movement

For the past three years I have been working with a group in my current city of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania that is fighting against water privatization and to maintain public, transparent, and democratic control of our water (while also working to address the significant lead contamination problem ). When living in Brazil over a decade ago, I visited the Palmares II settlement of the MST. I also learned about conflicts and threats around resources, including water. When I returned to the United States, I began a campaign to “ban bottled water” on my college campus and worked to educate students and faculty on why water should not be a commodity. After college I worked as a community organizer in Jacksonville, Florida for four years. As I have embarked on graduate school, one of the challenges that I have confronted is how I might be able to bring together my work as an activist and organizer with my academic study. How can knowledge be built collaboratively to be a part of changing the world? What can social movement actors teach social movement scholars about knowledge production?

Data and Methods

From June 12-July 18, 2018 I conducted preliminary fieldwork in Brazil. My dissertation research is on how movements organize around the right to water. This paper emerged out of that work. Using snowball sampling, I conducted 24 formal semi-structured interviews. I also have 140-plus hours of participant observation, as well as over a dozen informal interviews. Relying on the connections of a founding member of the U.S. Solidarity Network for MAB, I established contacts with two key leaders of MAB. These leaders facilitated making more contacts, and I had the opportunity to conduct research on MAB as well as other partner organizations and unions. Movement leaders also shared with me an abundant amount of published material, including books, pamphlets, posters, and other literature.

I come to the doctoral study of social movements following eight years working as an organizer. I want to acknowledge that the idea of co-research is not new: the Italian practice of “coresearch” as articulated by Romano Alquait (and others) in the 1950s and 1960s collaboration between workers and researchers (sociologists in particular) could produce a new form of knowledge (Mohandesi; Haider, 2018 3) and build revolutionary theory. Or, as Carolina Alonso Bejarano and her coauthors (2019: 137) write of their endeavor to decolonize the process of ethnography, “this approach did not originate with us, the authors of this book. Our intervention stands on the shoulders of the many individuals, schools, and perspectives variously labeled feminist, native, Black, collaborative, World, applied, engaged, practicing, and activist, to name but a few”.

I recognize that my work on movement theory must be done in collaboration with the movements themselves, and that I keep in check my own positionality and privilege as a white, cisgender woman from the United States- of which mere acknowledgement is insufficient , but rather a starting point. Race, class, gender, sex, and geographic location all matter. I aim to keep in constant consideration my own epistemological stance as I conduct my data collection, analysis, and writing, and to position the knowledge of the movements I study at the center of my work. A critical aspect of academic activism requires not only being aware of power dynamics, but also the generation of mechanisms for collaborative/co-research.

This is a point to which I became increasingly attuned during my preliminary dissertation fieldwork, during formal interviews, informal conversations, and participant observation. I had many conversations and answered questions about the water activism in which I am engaged in the United States; how things are different and similar; and what we might learn from each other-including the need to build more solidarity networks, especially as threats around water have global implications which are only expected to increase. I was transparent about my role as an activist and organizer, and also as a PhD student who was conducting formal research with the intent to publish. I take these conversations seriously; they inform the core of my work, and why I do it. In my larger academic trajectory, I seek to explore how to generate true “co-research.”

The work of activist research and co-research (which I see as related but not synonymous) is a constant and changing process of reflexivity. There is not a clear path nor a specific end goal. One critical component of this as well, for me, is to work to make sure that I produce work that is written in Portuguese and/or work to translate the English version into Portuguese. On the other hand, I am also cognizant of how MAB is not well-known (even among activists on the Left) in the United States. As MAB leaders also told me, there is, then, also a need to share the work and knowledge of this movement in English. In terms of my process with this specific paper, I have communicated my intent to write on this topic and shared the Call for Papers for this special issue with leaders in MAB, and they expressed their support for it. I have also shared drafts of this article, and received input, including on which pictures to share, and how to credit/cite MAB leaders (beyond the formal ethics review committees in both the United States and Brazil through which my project had approval).

Results

My findings suggest that MAB is working to build and strengthen networks both nationally and globally, and that they work with a broad range of groups. I found that MAB has a focused and intentional effort to bring women, youth, and other historically disenfranchised groups into leadership. They articulate the importance of working to not replicate hierarchical structures (including those of patriarchy and heterosexism) within their own internal structure. The focus of this paper, however, is on knowledge production, and what academia might learn from movements-and MAB specifically. The MST-with whom MAB works closely and out of which some members of MAB have come-has its own press that produces and publishes books. MAB and partner movements are producers of knowledge, not simply movements to be studied by researchers. While this is not a novel assertion-as I note above-I contend that the dominant narrative that persists (within the United States in particular) is the idea that social movement scholars ought to remain the impartial observer, analyzing how movements fail or succeed.

In Figure 1 (above) I outline some of the ways through which academia might learn from movements, illustrating both why this is needed and how I observe MAB does this. Specifically, I think about the above figure in the context of three areas: framing the struggle, leadership, and revolutionary memory, each of which will now be discussed in turn.

Framing the struggle for a new world4

In the course of my preliminary dissertation fieldwork during the summer of 2018, I observed how Brazil’s MAB emphasizes that their work is not only to resist the current exploitative system, but to create a new way of living and being that respects and honors human rights. MAB moves beyond criticism of the current system and offers a vision of what could be-of what I would call “alter-globalization.” MAB points to capitalism as the problem and argues that the right to water is inextricably linked with the right to land, to energy, to food, to education, to safety from violence, to self-determination and to sovereignty. MAB’s fight focuses on rights and the idea of the collective-rather than profits and the individual-at the center of how society should be structured. It is a radical politics that aligns well with what Gianpaolo Baiocchi (2018: 95) describes as “popular sovereignty”-both a theory of democracy and a “transformative political project”. It is about the imagination and construction of alternatives to the world as it is-but the path there is not yet built, it is being made.

FIGURE 1 Movements as Producers of Knowledge

| Why we need it | How MAB does it | |

| Asking new questions | Academia encourages normal science, incremental questions | Imagining new futures; options previously not thought possible |

| Asking normative questions | Academia encourages leaving social justice outside | Imagining new futures; options we had not thought possible based on first-hand knowledge and experience |

| Linking questions/ struggles | Academia encourages specialization at the expense of linking struggles | Organizing and solidarity work across movements including at the local, national, and global level |

| Building collaborative knowledge networks | Academia (especially in the United States) encourages competition, building individual profiles | Solidarity work across movements plus empowering marginalized groups; fostering collaborative/bottom-up leadership |

| Making positionality visible | Academia strips us of our identities; the unexamined norms are therefore Western/male and so on; problem of methodological nationalism | Making identities, histories (individual, national, and world) of oppression central |

| Drawing on learned histories | Academia encourages innovation, finding something new; at the expense of learning from the past; methodological nationalism | Focus on knowing/learning from history (ies); memories of resistance |

| Guiding cultural narratives | Research encouraged to be esoteric/ uninspiring/apolitical | Use of storytelling; cultural work; consciousness-raising |

| Broadening audience/ movement | Research produced by and for “experts” only; objective and “apolitical” | Consciousness work plus organizing across movements/international solidarity work |

Figure source: Author

People saw their work as a struggle for the “commons” -including food, water, land. These things could not be separated5. Nor could they be separated from the struggle for livelihood-for the right to exist and have a livelihood. As one woman who is a part of organizing her neighborhood in Belém (and has been involved in struggles for racial and social justice for decades) put it: “é uma luta para direito morar” 6 (personal interview, Summer 2018). It is a fight for access to water, sanitation, education, transportation, and healthcare. It is the right to be free from police violence because of the color of your skin. To have a right to a quality of life. People for the most part did not become involved because of the question of water-although some did. Many leaders in MAB are themselves atingidos7 whose life and/or that of their families have been affected by dams. Some have also come from previously being involved in other social movements, including the MST. Most are involved in the struggle for justice for those affected by dams, and against the privatization of water, but also see their work as a part of the larger struggle for the rights of workers, the poor, women, and the marginalized (fieldnotes, Summer 2018).

One of the things that struck me is the way in which MAB frames its work: MAB uses stories to tell its story. For example, the account of Nicinha, an atingida murdered in January 2016 for protesting a dam in her community, is an important one to MAB (fieldnotes, Summer 2018). Her story is then connected to the phrase, “mulheres, agua e energia não são mercadorias” 8. This expands to the point that MAB’s efforts are neither specifically urban nor specifically rural: the fight for access to water is for everyone, everywhere9. In this sense, “Todos somos atingidos” 10.

The discussion of Nicinha (see Appendix A, Image 2) and the importance of stories-narratives-also brings to mind the importance of mística. Abdurazack Karriem (2009) has written on this as it relates to the MST. Karriem argues that in the MST theory informs practice and practice informs theory. In the beginning of the formation of the MST, Karriem (2009: 319) argues that liberation theologians served the role of the “organic intellectual” by raising consciousness, operating within the “cultural realm of common sense or the folklore of the landless”. Catholic values of suffering and redemption form the MST “mística,” with most meetings starting with a play that utilizes folklore and acknowledges historical figures in the fight for justice (Karriem, 2009: 319). They accomplished this through creating their own symbolism-a flag, songs, poetry, theatre-that is displayed and used at movement gatherings. I see this exact same process happening in MAB.

The use of mística operates as a mechanism of economic, political, and cultural organization. It is a part of the fight against cultural hegemony-Antonio Gramsci’s notion that dominant ideas, assumptions and stereotypes of how the world ought to be can hold great power over people, affecting their daily experiences and consciousness (Gramsci, 2000; Moore, 1996: 127). This concept is applicable to the work of MAB, which has constructed an alternate way of viewing social, economic, cultural and environmental relationships. In so doing, MAB is fighting against deeply-held assumptions about land rights, control of resources, and economy.

During the evaluation of a weekend-long training for new militantes that I attended, one of the participants stated that there needed to be more “mais mistica” in it (fieldnotes, Summer 2018) 11. This struck me, because as an outsider, I found the story-telling vehicle to be quite present and compelling. Yet, the point was made that there could have been more of it. This speaks to the idea that MAB’s struggle is not just about fighting the “system” but about consciousness/cultural work. The inclusion and focus on mística is present in ways with which I am not familiar in the U.S. movement, and I found it to be powerful. I am interested in exploring more about how this is developed and what it might mean for movement strength (including when thinking about the potential for a transnational right-to-water movement).

Leadership

Many of the pamphlets I was given contained questions for discussion and debate (MAB, 2018). In training sessions, a common format included reading material together, answering questions, and having group discussion on those questions. MAB has adopted this strategy as an important way of building literacy and leadership: both in the sense of actual literacy and also as literacy in the history of past and present resistance and movement-building12. A recurrent theme was the importance of empowering women, children and other historically disenfranchised groups. As one member of the coordinating committee in São Paulo told me: MAB’s model is one woman, one man, and one youth (under 30). Once members turn thirty they are expected to take their skills and help organize somewhere else, while opening up the space for someone new (personal interview and fieldnotes, Summer 2018). One of the things that I noted was the vibrancy of the movement and the inclusion and active leadership of young people in its efforts. There is a deep and intentional focus on pedagogy and leadership development, specifically focused around the inclusion of women, youth, and children.

In particular, I observed this when I had the privilege of being invited to attend the third step (out of four or five) of the Formaçãode Militantes do MAB conducted in a rural community a few hours outside of Rio de Janeiro that continues its history of struggle around the construction of dams. During the course of this weekend-long training I observed and learned how MAB is articulating a clear and intentional fight against interlocking systems of oppression: classism, racism, heterosexism, and patriarchy. These are all seen as interlinked with capitalism, which is seen as the root cause of the problem. Articulating a different way or alter-globalization is a process of education and growth, where people learn through the format of lectures, conversations and discussions. One of the foci of social movement studies is outcomes (Staggenborg; Lecomte, 2009; Wood; Staggenborg; Stalker; Kutz-Flamenbaum, 2017). MAB’s efforts are ongoing, and while knowing what the long-term outcomes will be is perhaps impossible to predict, one tangible outcome is empowering individuals historically disenfranchised and excluded from the political system to become leaders. The focus on leadership then leads to other significant lessons learned, which I discuss in turn.

Revolutionary memory, intersecting oppressions, and transnational resistance

MAB fights against the idea that human life is a commodity. Water is essential for life, so when it is commodified, life itself is commodified. This extends to energy in general, which forms the basis of their motto, “water and energy are not commodities!” They articulate a model of teaching and empowering disenfranchised people-the poor, the peasants, the workers, women, LGBT, youth-to be leaders. I was struck by the deep understanding conveyed by MAB that all oppression and injustice is connected. That is, the death of an LGBT person is related to the dispossession of a peasant farmer from their land because of a dam project. The death of a woman from intimate partner violence is related to the child that dies from lack of clean drinking water. This is why it is a “lutapopular” 13. At the core of this fight is the understanding that capitalism feeds systems of exploitation because it requires dispossession and exploitation to function. In order to build a world where LGBTQIA people are respected, where women are empowered, where children don’t die, and where people aren’t driven from their homelands, we have to fight the capitalist system.

In answer to the question of “why do we study this?” posed by one of the leaders of the Formação de Militantes do MAB, the answer was “Gente faz nada sem energia. Mesmacoisacom agua-gente faz nadasem14agua” 15. This is what makes water a right- you cannot exist without it (fieldnotes, Summer 2018). A fight for water rights is at the core a fight against commodifying life, human and otherwise. An elderly man who had spent his life farming and who t was discussing the changes he had seen, including the waterfalls that are no longer there because of dams, put it this way: “a gente precisa respeitar o limite do rio” 16. His statement was followed by the point that the root of the problem is that nature and people have been privatized. Capitalism does not observe limits; it creates problems and then tries to create a “sustainable” solution, which is not possible because the system of capitalism is inherently at odds with the idea that life has intrinsic, non-monetary value (fieldnotes, Summer 2018).

While MAB’s analysis points to capitalism as the root of injustice and environmental degradation, my interviews within MAB reflect a repeated theme of the importance of empowering those historically excluded from the political process. By extension, then, fighting oppression in all forms within the larger socio-political economic system also means confronting internal/organizational forms of oppression. As one woman, a member of MAB in Belém told me, there is a lot of intentionality around empowering women to organize and to lead in all parts of coordinating the movement because historically they have been subject to machismo, patriarchy, and violation of rights. There has been, she said, an “invisibilidade de seus direitos” 17 (personal interview, Summer 2018). As such, there is an emphasis on the idea that knowledge production is a collective process and critical to articulating an alternative way of organizing life. Another member of MAB’s coordinating committee disclosed to me the depths of this commitment, delineating MAB’s long term vision and game plan with goals developed for the next five years, twelve years, and up until 2070 (personal interview, Summer 2018).

On a bulletin board in the MAB headquarters (pictured below) in Rio de Janeiro, in the left- hand corner is a poster for a book (that has been adapted into a film as well) 18 produced by MAB: Arpilleras Bordando a Resistência.19Arpilleras is the term used for the colorful pictures made in many parts of Latin America by appliquéing scraps of fabric onto a hessian backing. During the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile this medium became politically significant since working-class women used them to depict the reality of life under military rule. In the Arpilleras project, MAB followed in this model to chronicle the struggle in Brazil against human rights violations. The point is made that over 16 different human rights violations are time and again chronicled during and after the construction of dams. The book also includes pages explaining the history of this artform in Chile and includes works from women affected by dam projects (Arpilleras Bordando a Resistência 2018). Numerous MAB leaders also raised this point with me in interviews and conversations (fieldnotes, Summer 2018). While focused on the Brazil anti-dam struggle, this book also details conflicts in a dozen other countries, thereby depicting the transnational aspect of the struggle. It is a global fight against oppression and for human rights. But in drawing on the example and history of arpilleras, this project also illustrates the importance of revolutionary memory in comprehending the past (see Appendix A, Images 3 and 4).

MAB emphasizes education and understanding how historical processes inform present-day struggles. This speaks to the importance of Marxist theory, liberation theology, and a liberatory model of education based on the work of Paulo Freire.

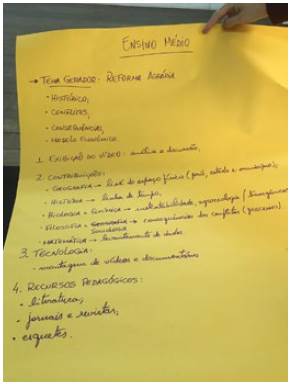

In addition to the Formação de Militantes do MAB I attended a morning-long training led by professors and movement leaders on the history of the fight for land in the state of Rio de Janeiro. This extension project training was held in the town of Cachoeiras de Macacu and made possible by the collaboration of several universities, the municipal government and MAB. The objectives of the project included calling attention to the importance of memory in the fight for land and the contribution of memory to the work of MAB in the resistance of farmers threatened by a dam construction project on the Rio Guapiaçu. The project also serves to provide an opportunity for university students and community members to participate in a project developing pedagogical activities for use with school-age children (fieldnotes, Summer 2018; Material didático para as oficinas do projeto de extensão, 2018). In this training (and Formação de Militantes) the starting point was the legacy of colonialism and appropriation of resources. But it is not just the history of oppression and repression that is taught: the memory of resistance is also important to have strength and hope for the present. I was invited to join in the breakout group for creating a syllabus for high school students on the history of land reform. Image 5 (see Appendix A) shows what we created20.

Another example of the importance of resistance struggles occurred in the first few moments of the Formação de Militantes training. For the “icebreaker,” we were all blindfolded as some of the leaders read a poem by Hailton Mangabeira, “40 Horas na Memória” about Paulo Freire and how we remember his work for literacy, consciousness raising, and creating a more liberatory world. One by one, our blindfolds were removed. We were then put into groups remembering historical figures and leaders of resistance: Nicinha, Zumbi, Paulo Freire, Ze Pureza21. This exercise demonstrated the importance of pedagogy and history, and also the emphasis on collaborative learning, conducted in an interactive model to include and engage people. Miguel Carter, in his writing on the MST, detailed the emphasis on education and “raising popular consciousness” of its members, using both the pedagogy of Paulo Freire as well as its own materials (Carter, 2011: 201). This same emphasis, I argue, is present in MAB.

Drawing heavily on Paulo Freire’s (1972)Pedagogy of the Oppressed, in trainings MAB focuses on collaborative learning and literacy. The model they use of small break-out groups where people take turns reading passages helps people learn to read. There is an intentional effort to fight against interlocking systems of oppression: classism, racism, heterosexism, and patriarchy, as these are viewed as interlinked with the root cause of capitalism (fieldnotes, Summer 2018). Or, as an MAB leader put it: “É uma luta global; uma luta pela humanidade” 22 (personal interview, Summer 2018). During this weekend training, we were also asked to turn in cell phones, which served the purpose of encouraging people to be present with each other and the information.

Finally, I observed the importance to MAB of the history and victory of the Cochabamba, Bolivia struggle. One of the most striking-and successful-examples of resistance against water privatization occurred there when thousands of residents took to the streets to protest. People worked together for change: they argued that water is a social good and won against the money power that sees it as a commodity. Over the course of eight days in April 2000, 100,000 people mobilized, formed blockades that cut off access to the highway, and occupied the city center. Activists also took over Aguas del Tunari’s offices and refused to move until their demands had been met. This culminated with concessions from the government and the corporation Aguas del Tunari (a subsidiary of Suez, one of the largest corporations involved in water privatization) (Dangl, 2014: 306; Olivera; Lewis, 2004: 37-39).

Oscar Olivera (one of the principal leaders of the resistance in Bolivia) has spoken at the MAB national conference, and the struggle is referenced at various times in various ways (fieldnotes, Summer 2018). During the training an animated film detailing the Cochabamba struggle was shown. The film is introduced by a MAB leader who explains that while the content is made accessible to children, the message remains universal and profound. The film is about appropriating water from camponeses in Bolivia, and it was shown as an example of hope. After the film the point was made that a few years ago people from Bolivia came to Brazil and talked to MAB; it is where they got the sign that hangs in the room “sin agua, no hay chichi, no hay cachaça” 23 (fieldnotes, Summer 2018). The Bolivia activists also gifted a tree to MAB as a sign of solidarity (see Appendix A, Image 6).

There are important lessons to be noted from the mobilization and resistance in Bolivia, and how that story remains important to the Brazilian struggle. Bolivia illustrates the importance of transnational solidarity in the fight against water privatization-both as a learning network for tactics and strategies but also as an example of hope and inspiration. Indeed, MAB is a formal member of La Via Campesina (LVC), a “peasant internationalism” (to use Martınez-Torres and Rosset’s (2010) phrase) around a shared identity to gain food sovereignty. LVC is also concerned with climate change and water issues, since both can profoundly affect agriculture-a point also articulated by MAB. As noted earlier, MAB works closely with other members of LVC such as the MST and MPA. Leaders from MPA attended the last day of the training to share their stories and struggles, and discuss the importance of solidarity and working together (see Appendix A, Image 7).

These solidarity alliances24 are also important because they demonstrate the strength of peasant movements. Peasants have not become “obscure,” even as, to draw on Philip McMichael (2008: 37), “the narrative of capitalist modernity” has seen the peasantry as something outdated, that would disappear with progress and development. LVC-and all of its members including MAB (and MPA and MST) counter the dismissive notion of peasants being encapsulated as historical relics, and asserts instead peoples’ natural rights to self-determination as well as rights to both humanistic and legal objections to expulsions masked as “progress” in the form of capitalist globalization. Finally, LVC is important as a global South-led transnational movement focusing on fighting various and intersecting forms of oppression.

The present political moment in Brazil, in the United States, and in many other places (not to mention the worldwide crisis of climate change that is faced by the entire globe) is daunting. As such, the importance of movements learning and working together in solidarity is now more crucial than ever. In my research this summer I observed the importance of knowledge production and how this is a critical piece of the work accomplished by MAB. Moreover, numerous Brazilian academics have conducted research and written papers on the work of MAB-yet their work remains relatively unknown in the United States. Knowledge production is also not just from movement to scholars, but from Southern scholars to Northern scholars as well. In an interview with two university professors in Belém, I was encouraged by the collegial acknowledgement that the work I am doing around water is critical and then urged, as an equal imperative, that we form a network of researchers to share information. The point was made that in Brazil obtaining information on the activities of corporations (and governments) related to the privatization of water is difficult, since there is little transparency or mechanisms to access information (personal interviews, Summer 2018).

A common point articulated to me in various ways was that the fight against commodifying water and for life is “uma luta local, nacional, e internacional” 25 (personal interviews and fieldnotes, Summer 2018). MAB leaders discussed the importance of the Fórum Alternativo Mundial da Água (FAMA or World Alternative Forum on Water) as pivotal for building the national and international aspects of the movement. Held in Brasilia in Spring 2018 as an alternative to the Fórum Mundial da Água (FMA or World Forum on Water), FAMA was created in opposition to FMA, which had been overrun by corporate interests seeking to privatize and control water (see Appendix A, Image 8). As those involved in FAMA refer to it, FMA is the “forum of corporations” (Central Única dos Trabalhadores de São Paulo; Fundação Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 2017; and fieldnotes, Summer 2018).

Conclusion

What capitalism does well is to use culture to make us think that this system is in our interest, and to reduce the amount of counter-hegemonic promotions and ideas that we see (Sklair, 1997: 530). Hegemony works by controlling knowledge and the production of knowledge. One alternative to the logic of capitalism is the logic of rights26. A powerful and important example of this discourse of rights comes from social movements fighting for them, as I have demonstrated here through the case of MAB. Not only a producer of knowledge, MAB is also an organizing energy to create a different framework for life-an example of alter-globalizations. Here, I return to the questions I posed at the beginning of this essay: What can academia learn from movements? What is the role of knowledge production in the construction of a transnational social movement? How do I produce research that does not reinforce power hierarchies? How do we create collaborative research? And how do these questions speak to the larger area of knowledge production?

In many of the informal conversations had beyond the formal two dozen interviews conducted, I was asked questions about the struggle against privatizing water in the United States; some people suggested that perhaps that U.S. water rights movements could learn from MAB. I shared my own organizing history with people, and I think that helped build trust and rapport; but I am also engaged in this issue because I believe that water is a human right and not a commodity. I strive to conduct sound research, but I cannot pretend to be an “impartial” researcher while extracting knowledge from people for my own benefit. After the first interview I conducted on my research trip, I was asked questions about my interest in water and what the situation looked like in the U.S. The MAB leader told me that she (and MAB) wanted to connect and learn from one another (personal interview, Summer 2018).

In another conversation, I was asked by a member of MAB (who is working on a graduate degree in Geography), “What type of theory do you use?” He went on to talk about Boaventura de Sousa Santos, and the importance of Global South knowledge production. Additionally, he and several other MAB leaders talked about David Harvey (2012) (who is relatively popular in Brazil and often translated into Portuguese). I was then asked, “Are you going to translate any of your work into Portuguese?” I responded that I intended to but would need to complete my work first in English (personal interview, Summer 2018). But the question of language and translations is another critical aspect to consider in the discussion of knowledge production. This made me think about my desire to have shared knowledge production. There is no guidebook for how to create “co-research”; it is a process of learning with and from each other-one that is unfolding and one to which I do not have all the answers. It is how I think about my role, how I conduct research, and what I do with the knowledge produced.

At a moment in history when right-wing governments are coming to power-including in Brazil-the struggle to create and maintain alter-globalizations becomes even more challenging. MAB and other movements, however, are continuing to resist, and the work continues-even in the face of rollbacks on human rights and environmental protections (MAB, 2019; Schroering, 2019). As comrades in MAB have shared with me, solidarity between movements and across national borders in this particular moment have become even more critical. A starting point for this, I argue, is to learn about, from, and with global South-led movements. As MAB says, “A luta continua!” 27.