The relations between China and the 17 countries of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) saw profound transformations between 2009 and 20191 2. In the space of a decade, what used to be at best a relationship of "mutual disengagement" (Kong, 2015) has been comprehensively deepened thanks in part to the institutionalization of the 16+1 regional platform for cooperation3, which officials from these countries recently declared to be "a pragmatic and useful platform for promoting cooperation between China and CEECs" and "an important part of the Europe-China relations" (Xinhua, 2019).

The results of the 2019 summit in Dubrovnik are indicative of this progress. Jakóbowski and Seroka (2019) note that close to 40 bilateral agreements were signed between China and the CEE countries in a single day in areas as diverse as market access for food and agricultural products, educational exchange, and development financing. The summit also marked its first instance of enlargement. Greece, which had been merely an observer state until then, became the 17th full member of the platform.

This quick turnabout in the relations between the two sides, and the central role played by 16+1 in it, brings up several questions that we wish to answer here: from the Chinese side, what reasons stand behind the establishment of 16+1? How does history play a role in its establishment and development since? And where is 16+1 headed?

To answer these questions, this article is divided into four sections. The first one recounts the historical context of China-CEE relations, dividing it into six periods. The second section reviews the literature seeking explanations about China's intent to develop the 16+1 platform, noting economic, political, and historical reasons. The third section points to the future of 16+1 given the concerns of the European Union (EU). Finally, there is a section on conclusions.

China-CEE Relations in a Historical Context

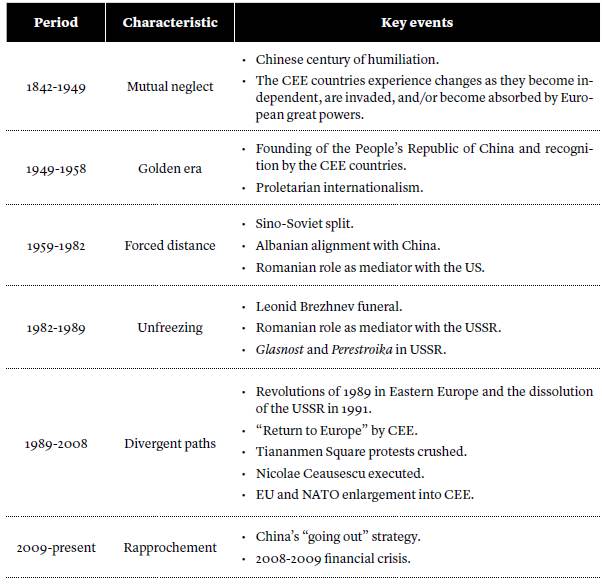

Relations between China and the CEE countries have seen ups and downs in the past century and a half, often mediated by the influence of great powers or large-scale international events. We establish here six distinct periods of relations between the two sides, which we list in Table 1 below and describe in the following paragraphs.

The first period is one of mutual negligence that spans the entirety of China's century of humiliation, beginning with its defeat at the hands of Great Britain in the First Opium War and the signing of the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842. Relations between the two sides in this period are non-existent at the official level. This can be explained mainly by two parallel dynamics. On the one hand, that most societies on both sides were in an early stage of transition toward becoming modern states, meaning that they often lacked the mechanisms by which to engage each other. China, for example, did not have a fully-functioning ministry of foreign affairs until 1901 (Spence, 1990: 235). Many CEE countries, on their part, lost their sovereignty during this period, as happened to Poland in 1939 in the context of the Second World War. On the other hand, these states were more concerned with their survival in the face of aggression by great powers than with establishing relations with each other. Relations may have occurred at the level of the individual, political movements, or political parties during this period, though the literature review so far has not revealed that. Although the two sides did not develop official relations in this period, this could be seen positively given that the CEE countries do not acquire the imperialist tinge that Western European countries are seen through in China (Callahan, 2011; Matura, 2019).

The second period began with the establishment of the People's Republic of China on October 1, 1949. This has been described as the "golden era" (Fürst; Tesař, 2014) of the relations between the two sides, motivated by a shared sense of comradeship and brotherhood as members of a single international proletarian movement (Slobodník, 2015). Spence (1990: 525) reminds us that the CEE countries were some of the first to diplomatically recognize the new government led by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in Beijing: the Soviet Union (which by then had absorbed some CEE countries like those of the Baltic subregion) on October 2, Bulgaria and Romania on October 3, and Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia on October 4. Relations also developed beyond the diplomatic level into practical aspects, like the creation of a shipping joint venture between China and Poland in 1951 (Turcsányi; Qiaoan, 2019). As will be explained in a later section, the Chinese see this period as the base of their contemporary relation with the CEE countries. However, it should be noted that relations with Yugoslavia were strained for the greater part of this period, given the ideological controversies surrounding the moves made by the Yugoslavian leader Josip Broz Tito to maintain a socialist line independent from that of the USSR4.

The straining of relations between China and the Soviet Union, starting around 1958, brings this second period to an end, giving way to a new period of forced distance between China and the CEE countries. During this period, the two Communist superpowers competed for the leadership of the Communist movement worldwide; other countries aligned with this movement were forced to take sides. Geography, power, and influence bring most CEE countries to the Soviet camp. Notwithstanding, there are two notable exceptions: Albania and Romania. Luthi (2015) says that the first country aligned with China for ideological reasons, even going so far as to protect it in a meeting of all communist parties in Bucharest in 1960, in which China was heavily criticized by all other East European parties. China paid back that support with aid following Albania's split with the USSR (Garver, 2012: 121). Meanwhile, Romania used its relation with China for political reasons as a way to balance Soviet influence. As a balancer, Romania served as the conduit for communication between the United States and China ahead of the visits by then-National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger and President Richard Nixon.

A gradual unfreezing of relations between China and the Soviet Union starting in 1982 allowed the reestablishment of the relations with the CEE countries, ushering in the fourth period. A driving force behind this normalization of relations is China's newfound focus on modernization and development, leaving ideological controversies to the side following the death of Mao Zedong in 1976. Perhaps because of this pragmatic focus on development, relations with the CEE countries centered almost exclusively on economic issues (Zubok, 2017). Once again, Romania played the role of mediator, this time transmitting messages between the two Communist superpowers in 1985 that led to the 1989 visit to Beijing by the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev (Garver, 2012: 432).

This period, however, proves to be short-lived. The differing results of revolutions in CEE and China in 1989 led the two sides down separate paths in the fifth period. The revolutions in CEE put new democratic governments in power that base their legitimacy on their explicit rejection of their Communist past. The same happened to the nascent states of the Baltic after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. During this period, the CEE countries turned their back on the East, seeking in stead to "return to the West" (Henderson, 1999). One way of achieving this was by joining the European Union, with all that it represents. Ten countries of the region joined the EU during this fifth period: the four Visegrad countries, the three Baltic countries, and Slovenia in 2004, and Bulgaria and Romania in 2007. Croatia joined the EU later, in 2013. The same 10 initial countries also joined NATO in this period; Albania, Croatia, Montenegro, and North Macedonia joined during the final period.

Just as democratic revolutions succeeded across CEE, protests erupted in China in 1989. Nonetheless, the government crushed these protests more firmly shutting the door to political reform. Both sides looked in horror at the experience of the other. In the eyes of the CEE countries, China has become "the quintessential example of the oppressive regime, a general symbol of 'other'" (Turcsányi; Qiaoan, 2019: 4). Meanwhile, the Chinese see the experience of CEE as a warning sign of what could happen if chaos is allowed to reign. The images of the corpse of the then-recently executed Romanian leader Nicolae Ceausescu and the short-term economic difficulties experienced by the newly-democratic countries of the region are used as evidence of the dangers of social disorder and uncontrolled economic transition. As a result, relations in this period were superficial.

The sixth period, which is the last one we review here, begins with the 2008-2009 financial crisis and the subsequent Euro crisis, which provided "an additional impetus for both China and the CEE countries to strengthen their economic relations" (Szunomár, 2018: 74). By this time, some countries in the region had become disillusioned: their initial excitement about returning to the West did not translate into immediate benefits. The data supports this perception. For example, a recent study by the European Trade Union Institute found that workers of the CEE countries that joined the EU are paid almost €1000 less per month than workers in Germany when living costs are considered (European Trade Union Confederation, 2017). There is also a generalized sense of being treated as second-class citizens by the more established members of the EU (Turcsányi, 2020: 71). The crises only added to this pain, as the markets that CEE countries became dependent on in Western Europe slowed down, importing less from them and withdrawing their capital (Szent-Iványi, 2017). It is precisely at this time that a rapidly developing China positions itself as an attractive alternative: a potential destination for goods and services offered by the region and a likely source of financing for development. The third section will explain more about the economic advances between the two sides.

From a more political point of view, the CEE countries have sought "strategic alternatives" (Golonka, 2012) to what is perceived as a one-sided dependence on the West. Moreover, the CEE countries see the developing relations with China as a way to diversify foreign contacts and, consequently, reduce risk (Salát, 2020).

Thus, there appears to be a perfect fit between the two sides, which enjoy a fragile rapprochement that lasts until today.

Vangeli (2018) posits that the idea of establishing a platform of cooperation between China and the CEE countries was first conceived during then-Vice President Xi Jinping's 2009 visit to Hungary. This was followed up in 2011 with a state visit to Hungary by then-Premier Wen Jiabao. The visit coincided with the first China-CEE business forum. In his speech to the participants, Premier Wen made a point of recalling China's "long-standing and deep friendship" with the CEE countries; he also proposed five points on which the two sides could base their cooperation: trade, investment, infrastructure construction cooperation, fiscal and financial cooperation, and people-to-people and cultural exchanges (Xinhua, 2011). A year later, in 2012, the prime ministers of the original 16 CEE countries and China met in Warsaw for the first summit of the 16+1 regional platform for cooperation. Save for 2020, the first year of the global coronavirus pandemic, they have met every year since, with the latest summit occurring in Beijing in 2021.

In the previous paragraphs, we have described the ups and downs of the relations between China and the CEE countries in the past century and a half. Several of these historical elements will help us understand China's motivations in establishing the 16+1 platform, which we explore in the following section. They will also help us understand some of the obstacles that have emerged between the two in recent years. We resolve this last point in the third section.

Motivations Behind the Establishment of the 16+1 Platform for Regional Cooperation

In the sixth period of China-CEE relations, the two sides found a good fit in each other in terms of needs and capacities. Nonetheless, this does not fully explain the motivations behind the creation of the 16+1 platform for regional cooperation. After all, another format of cooperation could have been created. There are also other regions of the world for which China has not developed similar mechanisms, bringing up questions on why this format was chosen for this region at this time. This section will seek to explain China's motivations behind that choice. Instead of providing a single answer, we have structured the answers given by the literature into three categories, which we present below.

The first set of answers is given directly by the Chinese government and state-backed think tanks. The Chinese position is that 16+1 exists to serve pragmatic, not ideological, ends (Xinhua, 2018a), especially those related to economic development.

This pragmatism goes back to the declarations made by the Chinese government in a 2003 policy paper on the EU (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China, 2003), the first official document on China's position vis-à-vis European countries. The policy paper contains three objectives, established by the government, for the relationship with the EU, which, as will be explained in the final section, also apply to the CEE countries, even those who are not members of the EU: promoting stable relations based on the principles of mutual respect, mutual trust, and seeking common ground while setting differences aside; deepening economic cooperation and trade; and expanding people-to-people and cultural exchange. While diverse goals are considered at the same time, Szczudlik-Tatar (2010) says that the focus since then has been on economic goals, as reflected in a report on CEE prepared by the Chinese Institutes of Contemporary International Relations, a government think tank that provides guidance on issues of foreign affairs. Non-Chinese authors like Szunomár (2018) also support the contention that China is driven principally by economic considerations, attracted to a great degree by the characteristics of the region's markets, for example, that they are developed, that Chinese companies face less competition in them, and that they promise lessons for later entry to more developed EU markets.

The latest Chinese government policy paper on the EU (Xinhua, 2018b) continues to reflect these objectives, but complements them with two new ones: cooperation in the political, security, and defense fields and cooperation in scientific research, innovation, emerging industries, and sustainable development. Moreover, the economic objective is expanded to include cooperation in the fiscal and financial fields. And China is explicit in its support for a united Europe that deepens its integration process. This support for union and integration is essential because it contradicts the allegations made by some that, in creating a mechanism that includes the CEE countries that are EU members, China seeks the splintering of the EU, something that will be discussed below.

The second set of answers is focused on political aspects. To explain why this regional format was chosen, we might draw valuable insights from Zhang (2019). He explains that China's relations with countries in peripheral regions have gone through four stages as China progressively becomes a great power with a more assertive foreign policy. In the first stage, from 1949 until 1991, bilateral relations dominated due to insufficient Chinese capacities to undertake more ambitious multilateral mechanisms. In the second stage, from 1991 to 1999, China began using regional mechanisms, though they were focused on crisis management, for example, those established with Russia and several Central Asian countries to address territorial disputes. The third stage, which goes from 2000 until 2012, sees China focusing more on win-win, cooperation-based development. Regional platforms like 16+1 and others were created during this period. The latest stage, which starts in 2013, is when China is more proactive in setting the agenda for a wider audience, as China has done for the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). A platform like 16+1, born under the conditions of the third stage, could be seen as having transitioned into the fourth stage. That China used a regional platform for cooperation with the CEE countries should then be seen as part of a general trend aligned with the country's new capabilities as a great power. Jakóbowski (2018) confirms this when he notes that the format initially used for CEE countries draws from a blueprint used earlier with African countries in the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) and used later with Latin America and Caribbean countries in the China-CELAC Forum.

Another answer is raised by scholars like Gaspers (2018), Scott (2018), and Simurina (2014), who perceive that China is more motivated by political objectives in its approximation to the CEE countries. These objectives are not always clearly articulated by the authors, but they suggest an intention to break up the EU or draw some of its members away from the Western sphere. The reasons given often allude to China's BRI, which runs through these countries on its way to more developed markets in Western Europe. They also frequently point to the potential use of China's alleged economic leverage in the region to extract political concessions from them, for example, in muting their criticisms of China's human rights record. It is noteworthy that none of the studies that assume this posture have carried out methodologically rigorous analyses from particular theoretical lenses, as they could if they assumed the neorealist paradigm of IR. Instead, other works that have done these analyses have found that China has few incentives to weaken the EU (Turcsányi, 2014) and have found no evidence that China's economic diplomacy affects Europe negatively (Garlick, 2019). Others (Matura, 2019) have found that China's economic standing in the region is small compared to that held by Western European states and that there is no evidence to support the contention that greater political closeness translates into more trade or political influence on issues like voting on anti-dumping measures.

The final set of answers touches on issues of memory-based identity. Turcsányi and Qiaoan (2019) have done the most exhaustive work on this topic. Their work suggests that China is likely to have been influenced by its memory of "traditional friendship" with the CEE countries in its choice of founding the 16+1 regional platform with them. That is not to say that this was the only reason, but it did play a supportive role, complementing the official economic objectives described earlier. Šteinbuka, Bērziņa-Čerenkova, and Sprūds (2019) back this claim, pointing out that during the early part of the sixth period, China viewed CEE as different from the rest of Europe and even part of the Global South.

We have not arrived at a definitive answer in this literature review; however, most evidence points to various factors acting at once in China's decision to establish the 16+1 regional platform for cooperation. Material interests and ideational aspects appear to have played a part. What has not yet been found are intentions to weaken the EU. Nevertheless, these perceptions have acted as one of the obstacles for a deeper relation between China and the CEE countries. The Chinese government has, in turn, sought to address these concerns by changing the functioning of 16+1 and its very perception of the CEE countries. We turn to these issues in the next section.

The Europeanization of 16+1

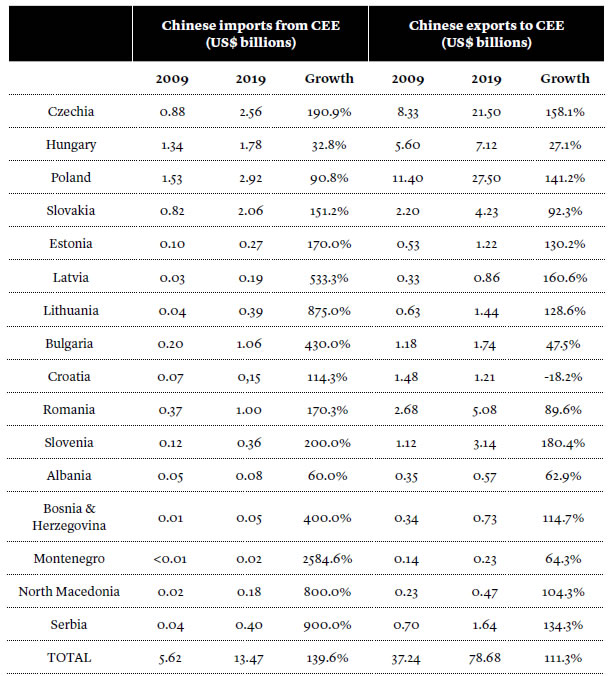

It has been ten years since the first 16+1 summit was held in Warsaw. Since then, 16+1 has made remarkable achievements. On the economic front, while remaining at low levels relative to the rest of the EU, Chinese trade and investment with the CEE countries has accelerated and remains on a positive path (Elteto; Szunomár, 2016). When it comes to trade, Table 2 shows that imports and exports in the region5 saw notable expansions between 2009 and 2019.

Chinese imports from CEE grew 139.6%, from US$5.62 billion in 2009 to US$13.47 billion in 2019. Meanwhile, Chinese exports to the region grew 111.3%, from US$37.24 billion to US$78.68 billion. In all cases except for one, there was growth during the period in exports and imports with every country.

While trade grew with every subregion of CEE, it is noteworthy that China's trade relations are particularly profound with the Visegrad countries, all of which are EU members. In 2019, the four countries represented 69.2% of all Chinese imports from the region and 76.7% of all Chinese exports to the region. This should not be surprising considering two related factors. First, they are among the largest in the region by population and GDP. Together, in 2019, they represented 54% of the CEE's population and 64% of its GDP (World Bank, 2022a; 2022b). Second, China is interested in developing economic ties with large CEE markets that belong to the EU, which can act as gateways to the rest of the EU market (De Castro; Vlčkova; Hnat, 2017). This reaffirms the literature that points to the pragmatic motivations behind China's establishment of 16+1.

At the same time, it must be said that, as encouraging as the figures on trade growth may be, the CEE countries represent only a small percentage of total Chinese trade with Europe (including Russia): in terms of Chinese imports, the region represents 4.03% of total imports from Europe, while in terms of exports, it represents 14% of all Chinese exports to the continent.

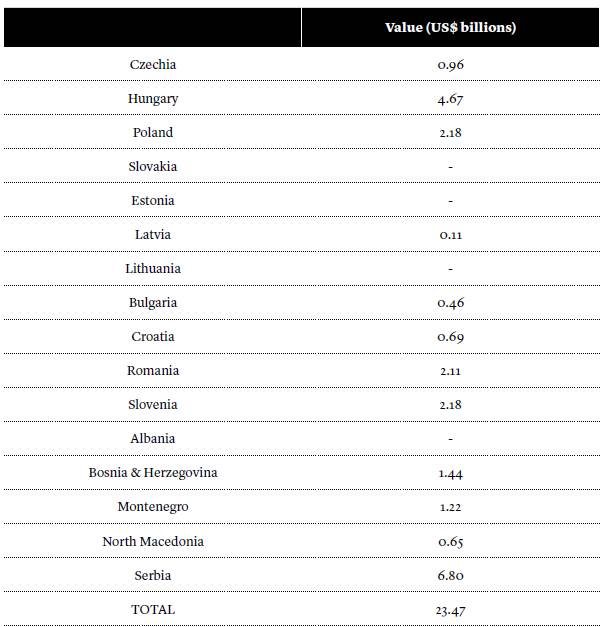

Regarding investment and participation in construction contracts, Table 3 shows a markedly different picture, one in which the Western Balkan states, along with Hungary, received the bulk of Chinese attention during the 2009-2019 period6.

TABLE 3 Chinese investment and participation in construction contracts in CEE, 2009-2019

Source: American Enterprise Institute (2022).

With US$10.11 billion, the Western Balkan states represent 43.08% of all Chinese investment and construction contracts in the region. Two reasons explain this. One is that these are relatively underdeveloped markets, with significant investment needs, especially in infrastructure. The other reason is that, unlike some of their regional peers, the Western Balkan states are not EU members, which means they do not otherwise have easy access to cheap funding sources from the region (Turcsányi, 2020). Therefore, this pushes them to seek alternative funding sources, including China.

Serbia, a non-EU member, has the largest Chinese investment and participation in construction contracts. Meanwhile, Hungary, an EU member, is in second place, with US$4.67 billion, representing 19.9% of the total for the region. That Hungary should welcome such notable amounts of Chinese capital has led to occasional allegations of "authoritarian advance" (Benner; Gaspers; Ohlberg; Poggetti; Shi-Kupfer, 2018) and to warnings of an alleged Chinese attempt to use a divide-and-conquer strategy against the EU through those members of 16+1 that are part of the EU (Gaspers, 2018; Holslag, 2017). Nonetheless, recent studies have shown that, instead ofpassive objects of great powers like China, countries like Hungary are active strategic players in their relations with them, in a way that "reflect the ambitions and calculations of the Hungarian side more than China's efforts to build up influence" (Salát, 2020: 125).

The data on trade and investment, while limited, points to three key considerations. First, that China-CEE economic relations are deepening, particularly since the establishment of the 16+1 platform for regional cooperation. Second, CEE is not a homogeneous region, and China's relation with the countries of the region responds to different national and occasionally subregional dynamics. Third, while the relations between the two sides grew in the period of study, they are still considerably less significant than those that the CEE countries hold with the rest of Europe.

Beyond the economic, on the institutional front, the 16+1 has experienced some changes that make it a more effective platform for cooperation. In addition to the yearly summits and release of guidelines of work, Jakóbowski (2018) highlights two innovations under 16+1: one, the establishment of contact mechanisms led by the CEE countries on specific areas of cooperation, eight of which have been created in areas as diverse as tourism promotion, investment promotion, inter-bank coordination, and logistics; two, the creation of an ad hoc mechanism for coordination between the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the 17 CEE national coordinators in Beijing that meet on a quarterly basis. Other regional platforms are now replicating these innovations for cooperation.

As remarkable as these achievements have been, obstacles continue to stand in the way. The literature points to four main obstacles. First, relations between China and the CEE countries are asymmetrical. Šteinbuka et al. (2019) discuss these asym metries from two interconnected angles: the large deficit between the CEE countries and China and the "neo-colonial pattern" by which the former primarily export low value-added goods while they import higher value-added goods and services from the latter. This situation has created a renewed sense of frustration among the CEE countries (Turcsányi, 2020).

A second obstacle is related to the dissonance between the two sides on their posture toward history. Once again, Turcsányi and Qiaoan (2019) have done the most sophisticated work on this topic. They find that while China initially understood the creation of 16+1 as a way of restoring the "traditional friendship" formed during the golden era of the second period, the CEE countries took this history as part of a dark past unrelated to their new democratic governments. This rejection is manifested in their approval of laws that prohibit the use of symbols related to Communism, actions to erase markers of the Communist past like changing the names of streets and taking down monuments to personages of the Communist era, and the creation of new spaces like museums to commemorate the suffering experienced during that period. It is noteworthy that this is true for most CEE countries, the exception being the Western Balkan countries, which have a more balanced posture toward their past.

Third, while the 16+1 format has acted as a recurrent space for dialogue and coordination between Chinese and CEE leaders, the agreements and commitments reached in it have not always translated into substantive action. China has also taken "the driving seat of the whole initiative" (Turcsányi, 2020: 65), which brings up questions about the extent to which participants can act on an equal footing. In this sense, it is no wonder that Lithuania left the initiative in 2021 following serious disagreements with China over the Taiwan question.

The fourth and final obstacle stems from the EU. As mentioned above, there are fears among observers of the possible detrimental effects of China on EU unity. Przychodniak (2018) gives the example of Hungary, an EU member, which has been seen as granting concessions to China given their increasingly strong bilateral relation. These concessions are seen in instances like Hungary's insistence on weakening the language of an EU declaration on China's actions in the South China Sea; another notable example is that of awarding a Chinese company the construction of the Hungary section of the Budapest-Belgrade Railway without following EU norms on open tenders.

The EU has not stayed silent in the face of these fears. In 2019, the European Commission published the region's strategic outlook on China. Under the outlook, China is perceived in a multifaceted way: as a partner for cooperation, a negotiating partner, an economic competitor, and a systemic rival (European Commission, 2019). Calls are made for EU members to maintain full unity and uphold EU values and norms.

In response to this, we observe that China has made significant concessions to appease the EU. Since 2013, observers from the EU and EU member states are allowed to participate in 16+1 summits and meetings of the contact mechanisms. Starting in 2018, their participation has increased, including setting the agenda and drafting the declarations and guidelines. 16+1 documents now consistently include language confirming that the platform conforms with the EU laws and regulations. Furthermore, most recently, there has been a Europeanization of the platform, insofar as "the negotiations in the areas that fall under the EU's competences (including transport, trade and investment regulations, customs, infrastructure) are set to be conducted based on the existing mechanisms of the EU-China dialogue" (Jakóbowski; Seroka, 2019). Through these actions, 16+1 has been effectively positioned as a middle layer in-between China's relationship with the EU and China's bilateral relations with European countries (Jakóbowski, 2018: 669).

Two key lessons can be drawn from these moves. One, that China has prioritized its relationship with the EU, understanding 16+1 as only an appendage. Two, that China has changed its perception of the CEE countries. Earlier, we noted that China initially saw CEE standing outside of Europe. Today, the decisions taken by China show that it sees the CEE countries as an integral part of the EU, disconnected from the shared history of communism that was once the focus.

Conclusion

This article set off with several questions on 16+1, the motivations behind its creation, and the future path that it could be expected to take. The previous sections have shown that the relation between China and the CEE countries is flexible, experiencing profound transformations in response to domestic, regional, and international occurrences. While history does not explain these transformations alone, it has played an important role that cannot be ignored.

As China places 16+1 below its relationship with the EU, and as it begins to understand CEE as an integral part of the EU, it will be interesting to see how it manages its memory of suffering at the hands of Europe. Will China lump the CEE countries as members of a European civilization that engaged in imperialist aggression against it? Will it prime new memories of Europe separate from those of its century of humiliation? Or will it try to distinguish between the CEE countries and the Western European countries, even as they all belong to the EU? These are all interesting questions worth taking up in future studies.

Future studies could also provide greater contributions in the way they address the limitations of this work. Key among them is that this work is concerned with Chinese motivations and perceptions, not with those of the individual CEE countries or subregions. Much like Salát (2020), new inquiries could advance our knowledge on the subject by starting from the proposition that the CEE countries, regardless of their power conditions relative to those of partners like China, have agency and are worthy of study. Similarly, there is more to be done in understanding the relation between China and the subregions of CEE. The steps taken in this direction will illuminate our understanding of the China-CEE relations and open new paths to analyzing China's relations with other regions of the world.