Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

International Journal of Psychological Research

Print version ISSN 2011-2084

int.j.psychol.res. vol.5 no.2 Medellín July/Dec. 2012

Researh article

Mediation effect of anger rumination on the relationship between dimensions of anger and anger control with mental health

El efecto de la rumiación agresiva como mediador en la relación entre la salud mental y las dimensiones de la ira y el control de ira

Mohammad Ali Besharata, Samane Pourbohloola

a Department of Psychology, University of Tehran, Iran

Mohammad Ali Besharat, Department of Psychology, University of Tehran, P. O. Box 14155-6456, Tehran, Iran, Tel: 009821 6111 7488, E-mail besharat@ut.ac.ir

Recibido/Received Junio 2 de 2012. Revisado/Revised Diciembre 1 de 2012. Aceptado/Accepted Diciembre 5 de 2012.

ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to examine mediation effect of anger rumination on the relationship between dimensions of anger and anger control including trait anger, state anger, anger in, anger out, anger-control in, and anger-control out with mental health in a sample of Iranian students. A total of 449 volunteer students (234 girls, 215 boys) were included in this study. All participants were asked to complete the Tehran Multidimensional Anger Scale (TMAS; Besharat, 2008), Anger Rumination Scale (ARS; Sukhodolsky, Golub, & Cromwell, 2001), and the Mental Health Inventory (MHI; Veit & Ware, 1983). Anger rumination mediated the relationship between dimensions of anger and anger control with mental health in opposite directions. Analysis of the data revealed that higher levels of anger was associated with lower levels of psychological well-being as well as higher levels of psychological distress. In contrast, higher levels of anger control were associated with higher levels of psychological well-being as well as lower levels of psychological distress. Mediation effect of anger rumination for the association of anger dimensions with mental health was full for psychological well-being and partial for psychological distress. Conversely, mediation effect of anger rumination for the association of anger control dimensions with mental health was partial for psychological well-being and full for psychological distress.

Key Words: Anger; anger control; anger rumination; mental health.

RESUMEN

El objetivo de este estudio fue examinar el efecto que posee la rumiación agresiva como mediador entre la salud mental y las dimensiones de la ira y control de ira, incluyendo ira-rasgo, ira-estado, ira interna, ira externa, control de ira interna y control de ira externa en una muestra de estudiantes iraníes. Un total de 449 estudiantes voluntarios (234 mujeres, 215 hombres) fueron incluidos en el estudio. A todos los participantes se les pidió completar la escala multidimensional de ira de Tehran (TMAS; Besharat, 2008), la escala de rumiación agresiva (ARS; Sukhodolsky, Golub, & Cromwell, 2001) y el inventario de salud mental (MHI; Veit & Ware, 1983). La rumiación agresiva medió la relación de las dimensiones de la ira y control de ira con salud mental en direcciones opuestas. El análisis de la información reveló que altos niveles de ira estaban asociados con bajos niveles de bienestar psicológico, así como también con altos niveles de angustia. Por el contrario, altos niveles de control de ira estaban asociados con niveles elevados de bienestar psicológico y bajos niveles de angustia. El efecto mediador de la rumiación agresiva para la relación entre las dimensiones de la ira y la salud mental fue completo para bienestar psicológico y parcial para angustia. Inversamente, el efecto mediador de la rumiación agresiva para la asociación entre las dimensiones del control de la ira y salud mental fue completo para angustia pero parcial en cuanto bienestar psicológico.

Palabras Clave: Ira; control de ira; rumiación agresiva; salud mental.

1. INTRODUCTION

Emotions may be activated under the effect of so many external and internal factors. Deffenbacher (1999) described differences between internal and external triggers of anger. External anger-provoking events are recognizable situations like encountering other's undesirable behavior. Internal triggers of anger are anger-provoking thoughts, memories, events and experiences like thinking about an undesirable encounter. Anger experiences are also shaped under the effect of cognitive appraisals, especially those related to intentionality, blameworthiness and unfairness (Kassinove & Sukhodolsky, 1995). Anger as a basic emotion is related to threat and negative appraisal, activate physiological responses and affect behavior tendencies (Averill, 1983; Kassinove & Sukhodolosky, 1995; Spielberger, Crane, Kearnes, Pellegrin, Rickman, 1991). Anger is accompanied by self-confirming beliefs and blaming others (Averill, 1983; Baumeister, Stillwell, & Wotman, 1990; Frijda, 1986; Rusting & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1998). Spielberger (1988) called phenomenology of anger as state-anger. State-anger is fleeting psychobiological feelings which vary from mild anger to intense anger in the sense of intensity, and include simultaneous activation of autonomic nervous system. Individual's tendency to experience state-anger more frequently and in response to a wide range of situations is called trait-anger. Research findings have shown that there is a relationship between anger and health indicators and long-term serious health risks including hypertension (e.g., Everson, Goldberg, Kaplan, Julkunen, & Salonen, 1998; Everson, et al., 1997; Harburg, Julius, Kaciroti, Gliberman, & Schork, 2003; Mendes de Leon, 1992; Siegman, Townsend, Blumenthal, Sorkin, & Civelek, 1998; Smith & Ruize, 2002), blood pressure (Bishop, Ngau, & Pek, 2008; Bongard & al'Absi, 2005; Everson et al., 1998; Gallagher, Yarnell, Sweetnam, Elwood, & Stansfeld, 1999; Harburg, Gliberman, Russel, & Cooper,1991; Hogan & Linden, 2005; Jorgersen, Johnson, Kolodziej, & Schreer, 1996; Spicer & Chamberlin, 1996; Suls, Wan, & Costa, 1995), chronic headache (Duckro, ChibnallTomazic, 1995; Materazzo, Chathcart, & Pritchard, 2000; Spierings & Van Hoof, 1996), asthma (Friedman & Booth-Keweley, 1987), and cancer (Thomas et al., 2000). Higher levels of anger also predict the mortality rate (Harburg et al., 2003).

Research also confirmed the association of anger with mental health indicators as well as mental disorders (Besharat, 2009a; Besharat & Hosseini, 2009; Fava & Rosenbaum, 1999; Moreno, Fuhriman, & Seldy, 1993). Troisi and D'Argenio (2004) revealed that trait-anger is associated with insecure attachment style. Robbins and Tanck (1997) confirmed the relationship between anger and depression in their research with a sample of normal population. Following past studies (Fava, et al., 1997; Moreno et al, 1993; Riley, Treiber, & Woods, 1989), Fava and Rosenbaum (1999) also supported the association between anger and depression in their study with a sample of depressed patients. In one of the newest studies (Painuly, Sharan, & Mattoo, 2007), the same results were replicated. Painuly, Sharan and Mattoo (2005) also revealed that anger is associated with two personality trait; neuroticism and psychoticism. Research (Besharat & Hoseini, 2009) have shown that anger is associated with aggressive behavior in athletes and with abnormal dimensions of perfectionism in a sample of students (Besharat, 2009a).

Another concept which is related to anger, but a distinct construct is anger rumination. Rumination consists of a repetitive process and unavoidable thinking about past experiences (Sukhodolosky et al., Langlois, Freeston, & Ladouceur, 2000a, 2000b; Watkins, 2004; Wenzlaff & Wegner, 2000). Anger rumination is described as thinking about anger. Based on this, anger rumination is a repetitively unavoidable cognitive process which appears during anger experience, it will be continued afterward and responsible for increase and continuation of anger. Research findings revealed that anger rumination serves to exacerbate anger outcomes through increasing the intensity and duration of anger (Rustings & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1998). Anger rumination increases negative affect and psychological distress through flaming anger (Besharat & Mohammad Mehr, 2009; Besharat, Hosseini, Mohammad Mehr, & Azizi, 2009; Bushman, 2002; Bushman, Baumeister, & Philips, 2001). Anger rumination is associated with seriousness, onset, relapse, duration and continuation of depression (Besharat & Mohammad Mehr, 2009; Besharat et al., 2009; Just & Alloy, 1997; Kuehner & Weber, 1999; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema, Parker, & Larson, 1994; Watkins, 2004). Ruminated thinking is often linked to negative thoughts (Lyubomirsky & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1995; Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991; Watkins, 2004), increase in aggression (Besharat & Hosseini, 2009) and decrease in psychological well-being (Besharat & Mohammad Mehr, 2009; Besharat et al., 2009). Rumination response style is associated with depressive mood, anxiety states and negative affect (Roberts, Gilboa, & Gotilb, 1998). Research findings have provided the preliminary evidence about the existence of a possible relationship between anger dimensions and anger rumination with mental health. The main research question is whether anger rumination mediates the relationship between dimensions of anger and mental health. This assumption can be set forth that probably dimensions of anger affect mental health through anger rumination: hypothesis I; dimensions of anger (including trait-anger, state-anger, anger in, anger out) are associated with higher levels of anger rumination as well as lower levels of psychological well-being. Hypothesis II; dimensions of anger control (including anger-control in and anger-control out) are associated with lower levels of anger rumination as well as higher levels of psychological well-being. Hypothesis III; anger dimensions (including trait-anger, state-anger, anger out, anger in) are associated with higher levels of anger rumination as well as higher levels of psychological distress. Hypothesis IV; dimensions of anger control (including anger-control out and anger-control in) are associated with lower levels of anger rumination as well as lower levels of psychological distress. Hypothesis V; the relationship between dimensions of anger and anger control with mental health is mediated by anger rumination.

2. METHODS

1. Participants and Procedure

Undergraduate students from the University of Tehran invited to take part in a "study on personality and behavior" via announcements in classrooms. A total of 449 of them (234 women [mean age: 21.95, age range: 18-29, SD: 2.37] and 215 men [mean age: 22.84, age range: 18-29, SD: 2.68]) agreed to participate. Questionnaires were completed in classes consisting of 20-30 students in the presence of the researchers who gave a brief description of the materials and answered questions. Measures were completed in classes during the initial recruit.

2. Measures

The Tehran Multidimensional Anger Scale-This is a 30-item questionnaire was developed to measure anger experience and expression in Iranian populations (Besharat, 2008). Each item is rated on a five-point Likert scale anchored by 1= almost never to 5= almost always. The Tehran Multidimensional Anger Scale consists of six subscales corresponding to the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (Spielberger, 1988): the Trait-Anger scale measures individual differences in the disposition to experience anger, the State-Anger scale measures the intensity of angry feelings at a particular time, the Anger-In scale measures the extent to which angry feelings are held in or suppressed, the Anger-Out scale measures the expression of anger toward other people or objects in the environment, and the anger-control scale measures the extent to which one attempts to control or reduce the expression of anger. The Tehran Multidimensional Anger Scale has received strong empirical support for its psychometric properties in Iranian populations. Internal consistency coefficients for the scales ranged from.82 to.94 indicating a strong relationship among the items of the scales. The Tehran Multidimensional Anger Scale showed good test-retest reliabilities ranged from.71 to.82 over a two-week period for different subscales (Besharat, 2008).

The Farsi version of the Anger Rumination Scale- This is a 19-item self-report measure of the tendency to think about current anger-provoking situations and to recall anger episodes from the past (Sukhodolsky et al., 2001). Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). It provides a total anger rumination score and also four subscales rating including Anger Afterthoughts, Thoughts of Revenge, Angry Memories, and Understanding of Causes. Adequate psychometric properties of the scale have been reported for the English (Sukhodolsky et al., 2001), the Chinese (Maxwell, Sukhodolsky, Chow, & Wong, 2005), and the Farsi (Besharat & Mohammad Mehr, 2009) versions. Cronbach alpha coefficients for anger afterthoughts, thoughts of revenge, angry memories, understanding of causes, and anger rumination (total score) were.95,.96,.97,.97, and.97, respectively. Strong evidence of the temporal stability obtained, with 1-mo. test-retest reliabilities of.93 for anger rumination (total score),.78 for anger afterthoughts,.82 for thoughts of revenge,.87 for angry memories, and.85 for understanding of causes (Besharat & Mohammad Mehr, 2009). For the present study, internal consistency coefficients were obtained between.93 and.96 for anger rumination scales.

The Mental Health Inventory- This is a 28-item measure that provides two sub-scales of Psychological Well-Being and Psychological Distress (Veit & Ware, 1983). Participants are asked to report how often they feel a variety of affective states on a five-point Likert scale anchored by 1= strongly disagree to 5= strongly agree. Veit and Ware used goodness-of-fit tests to determine the factor structure of the Mental Health Inventory for the general population. Five factors were identified: Anxiety, Depression, Loss of Behavioral/Emotional Control, Positive Affect, and Emotional Ties. Two negatively correlated (r= -.75) super ordinate factors of mental health are thought to account for the variations in self-reported mental health on the Mental Health Inventory: degree of psychological well-being and degree of psychological distress. Psychological Well-Being measures the extent to which people report positive mental health states and Psychological Distress measures the extent to which people report negative mental health states. Psychological Well-Being is divided into two factors: General Positive Affect and Emotional Ties. Psychological Distress is divided into three factors: Anxiety, Depression, and Loss of Behavioral and Emotional Control. Items in the Psychological Well-Being subset are evident in questions such as "How much of the time, during the past month, have you felt calm and peaceful?" An example of Psychological Distress is, "How much of the time, during the past month, have you felt difficulty trying to calm down?" Satisfactory psychometric properties of the English (Veit & Ware, 1983; Manne & Schnoll, 2001) and the Farsi (Besharat, 2009b) versions of the Mental Health Inventory have been reported.

3. RESULTS

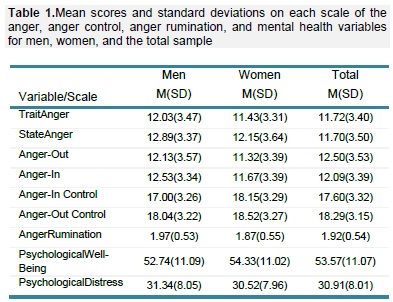

Table 1 shows means and standard deviations for the anger, anger control, anger rumination, and mental health variables for men, women, and the total sample.

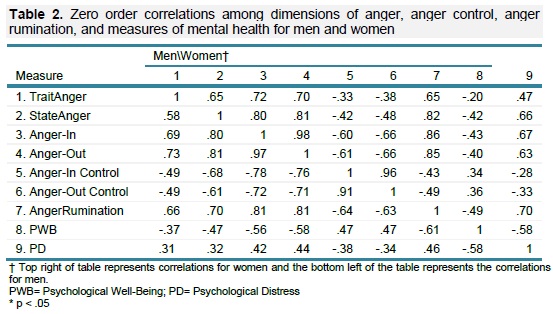

Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated among dimensions of anger, anger control, anger rumination, and measures of mental health for men and women. The results are summarized in table 2. As can be seen from Table 2, anger and anger rumination scores show significant negative correlations with psychological well-being and significant positive correlations with psychological distress. Conversely, anger control scores show significant positive correlations with psychological well-being and significant negative correlations with psychological distress.

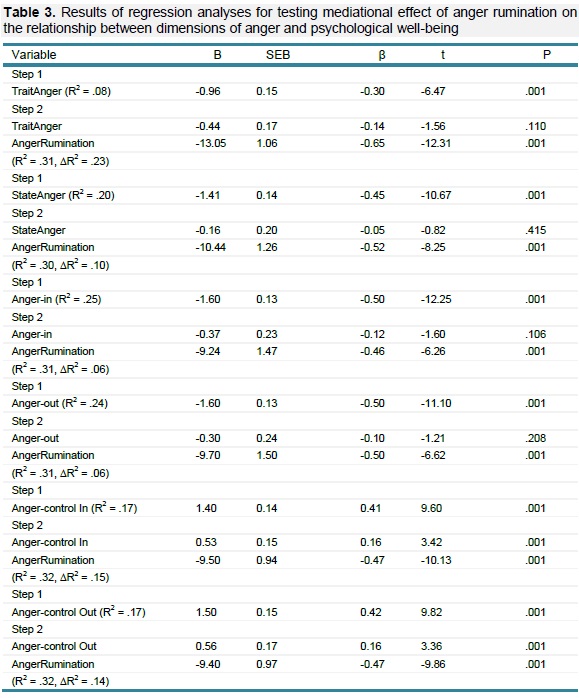

In order to examine the mediational effect of anger rumination on the relationship between dimensions of anger and psychological well-being, a series of two-step regression analyses were performed. The results are presented in table 3. As can be seen from Table 3, the β weight for trait anger dropped from -.29 to -.13. The Sobel test showed that this change was significant (t = -12.31, p <.001) while trait anger was no longer significant in the model (t = -1.56, p <.110). Similar results were found when the other dimensions of anger including state anger, anger-in, and anger-out were entered in the equation. These findings indicate that anger rumination fully mediated the relationship between dimensions of anger and psychological well-being (see Table 3).

Two-step regression analyses were also performed to examine the mediational effect of anger rumination on the relationship between dimensions of anger control and psychological well-being. As can be seen from Table 3, the β weight for anger-control dropped from.41 to.15. The Sobel test showed that although this change was significant (t = -10.13, p <.001), anger-control in also remained significant (t = 3.42, p <.001). Similar results were found when anger-control out was entered in the equation. These findings indicate that anger rumination partially mediated the relationship between dimensions of anger control and psychological well-being (see Table 3).

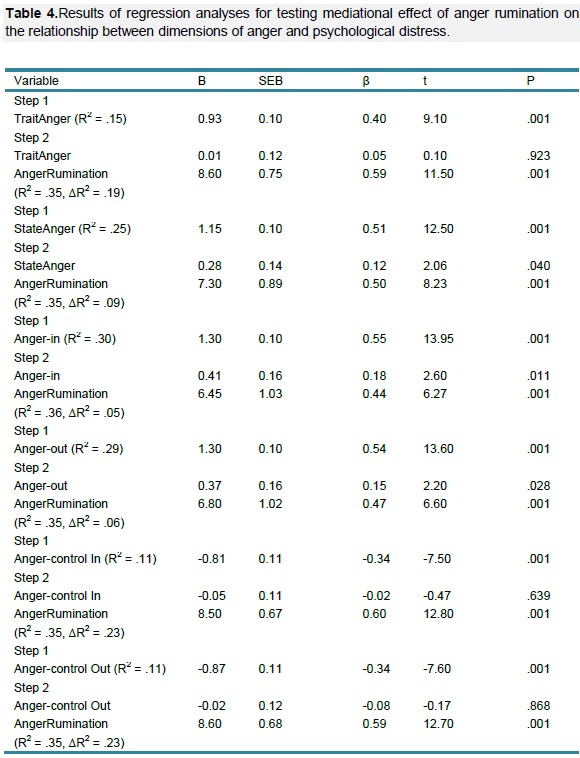

In order to examine the mediational effect of anger rumination on the relationship between dimensions of anger and psychological distress also a series of two-step regression analyses were performed. The results are presented in table 4. As can be seen from Table 4, the β weight for trait anger dropped from.39 to.005. The Sobel test showed that this change was significant (t = 11.54, p <.001) while trait anger was no longer significant in the model (t =.097, p <.923). Almost similar results were found when the other dimensions of anger including state anger, anger-in, and anger-out were entered in the equation. These findings indicate that anger rumination mediated the relationship between dimensions of anger and psychological distress (see Table 3).

Two-step regression analyses were also performed to examine the mediational effect of anger rumination on the relationship between dimensions of anger control and psychological distress. As can be seen from Table 3, the β weight for anger-control dropped from -.33 to -.02. The Sobel test showed that this change was significant (t = 12.78, p <.001), while anger-control was no longer significant in the model (t = -.470, p <.639). Similar results were found when anger-control out was entered in the equation. These findings indicate that anger rumination fully mediated the relationship between dimensions of anger control and psychological distress (see Table 4).

4. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The results of the present study revealed that anger rumination mediates the relationship between anger and anger control dimensions with psychological well-being and psychological distress. Statistical analysis of data defined that higher levels of anger including trait anger, state anger, anger in, and anger out are associated with lower levels of psychological well-being as well as higher levels of psychological distress through increasing the amount of anger rumination. Conversely, higher levels of anger control including anger-control in and anger-control out are associated with higher levels of psychological well-being as well as lower levels of psychological distress through decreasing the amount of anger rumination. The results also revealed that the relationship between dimensions of anger and anger control with mental health is mediated by anger rumination. These results have confirmed research hypotheses and have been explained based on following probabilities.

Research findings have shown that there is a direct relationship between anger and anger rumination (Langlois et al., 2000a, 2000b; Sukhodolsky et al., 2001; Watkins, 2004; Wenzlaff & Wegner, 2000). Hence it may be argued that anger directly increases anger rumination and anger rumination provides predisposition for reduction in psychological well-being. Research evidence about the link between anger rumination and mental health components (Besharat & Mohammad Mehr, 2009; Besharat et al., 2009; Bushman, 2002; Bushman et al., 2001; Just & Alloy, 1997; Kuehner & Weber, 1999; Lyubomirsky & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1995; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1994; Roberts et al., 1998; Rusting & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1998; Watkins, 2004) supports this explanation.

Anger experience as a basic emotion (Oatley, 1992) predisposes sense of threat and negative appraisal (Kassinove & Sukhodolsky, 1995). These experiences and cognitive appraisals activate or increase anger rumination (Rusting & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1998). Repetitively unavoidable thinking about anger-provoking experiences, the main characteristic of anger rumination (Langlois et al., 2000a, 2000b; Sukhodolosky et al., 2001; Watkins, 2004; Wenzalff & Wegner, 2000) affects mental health indicators. So, anger decreases psychological well-being and at the other hand increases psychological distress through activating and increasing anger rumination.

Beyond the unpleasant and at the same time unavoidable repetitive thoughts, anger rumination is associated with higher levels of negative affects(Besharat & Mohammad Mehr, 2009; Besharat et al., 2009; Bushman, 2002; Bushman et al., 2001), negative thoughts (Lyubomirsky & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1995; Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991; Watkins, 2004), and depressive mood and anxiety states (Roberts et al., 1998). Negative thoughts and affects are the main indicators of mental disorders versus mental health. Based on this explanation, anger might decrease psychological well-being and increase psychological distress, through increasing and decreasing anger rumination and its consequences.

Anger rumination, unavoidable repetitive process of thinking about past anger-provoking experiences (Langlois et al., 2000a, 200b; Sukhdolosky et al., 2001; Watkins, 2004; Wenzlaff & Wegner, 2000) reduces and declines anger management and control. Disability in managing anger increases the probability of appearing aggressive behaviors (Besharat & Hosseini, 2009). Anger rumination is associated with unhealthy behaviors (e.g. aggression) through weakening anger management, decreasing psychological well-being, and increasing psychological distress.

These explanations about the mediation effect of anger rumination on the association of anger dimensions with psychological well-being and distress can be set forth in opposite direction for the mediation effect of anger rumination on association of anger control dimensions with psychological well-being and distress. Anger control reduces anger rumination through preventing repetitive thoughts about anger-provoking experiences, decreasing negative appraisals of threatening situations as well as enhancing the ability to manage anger-provoking experiences. As mentioned above, lower levels of anger rumination might increase mental health indicators including higher levels of psychological well-being and lower levels of psychological distress.

The results of the present study revealed that mediation effect of anger rumination for the association of anger dimensions with mental health was full for psychological well-being and partial for psychological distress. Conversely, this mediation effect for the association of anger control dimensions with mental health was partial for psychological well-being and full for psychological distress. For more precise explanations, this new exploratory finding requires future researche in order to be confirmed or rejected, but at the same time it is representative of different efficacy and effectiveness coefficients of anger and anger control on mental health components. Anger has the most effectiveness on psychological distress. Because of this, the mediation effect of anger rumination between these two variables was partial. Anger control has the most effectiveness on psychological well-being, so the mediation effect of anger rumination between these two variables was partial. These findings also confirmed construct validity and factor structure validity of distinct dimensions of anger and anger control (Besharat, 2010).

4.1. Implications

In sum, the results of the present study supported the mediation effect of anger rumination on the relationship between dimensions of anger and anger control with mental health. In other words, anger dimensions and anger control sometimes fully and sometimes partially affect reduction or increment in mental health through anger rumination. Based on this, two groups of theoretical and practical implications should be mentioned for this study. At the theoretical levels, these research findings confirmed the validity and efficacy of anger concepts and constructs, anger control, and anger rumination particularly in the fields of psychopathology and clinical health psychology. Specifying the mediation effect of anger rumination would be helpful to complete anger theories in both fields of psychopathology and clinical health psychology. One of the most important implications of this study is the fact that studies related to anger and its effect on physical and mental health are incomplete without considering and assessing mediation effect of anger rumination and therefore should be interpreted cautiously. Considering the possible mediating variables in a scope beyond anger, would distinguish the place and the amount of theoretical usefulness of anger and anger control constructs and at the same time would highlight the kind of relationships and interactions of these constructs with other constructs. This systemic perspective to interconstruct interactions and relationships is one of the theoretical and meta theoretical requirements of psychological approaches. Without considering these requirements, validity, precision, correctness, and explanation power of the construct would be decreased severely.

At the practical level, analysis of mediation effect of anger rumination on the association of anger and anger control with mental health highlighted the role of this mediating variable, and at the same time revealed the healthful and traumatic outcomes of these construct in interaction with anger rumination. This obtained result has revealed the necessity of the preventive and constructive interventions in order to modify anger dimensions and anger control. Based on this, those studies related to effective and determinant variables on shaping anger dimensions and control are the main necessity in the field of research. In this direction, the most important studies are those related to personality variables, interpersonal variables, familial and social variables which affect anger and anger control, and in any of these fields there are broad unexplored scopes for researchers. In addition to this developmental and etiological approach to genesis and continuation of anger, the formulation of training and intervention programs for modifying characteristics related to these constructs, is one of the practical implications of this study.

4.2. Limitations

This study is done for the first time in Iranian population. So it requires to be replicated in different samples particularly, in patients (mental and physical), and it requires more empirical confirmation. Until that time the results of this study should be interpreted cautiously. Also, research design, examined sample, instrument and methodology impose some limitation on drawing a definite conclusion from this study, and this limitation should be considered.

5. REFERENCIAS

Averill, J. R. (1983). Studies on anger and aggression: Implications for theories of emotion. American Psychologist, 38, 1145-1160. [ Links ]

Baumeister, R. F., Stillwell, A. & Wotman, S. R. (1990). Victim and perpetrator accounts of interpersonal conflict: Autobiographical narratives about anger. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 994-1005. [ Links ]

Besharat M. A. (2008). Devalopment and validation of Tehran Multidimensional Anger Inventory. Unpublished, University of Tehran. [Farsi] [ Links ].

Besharat, M. A. (2009a). Perfectionism and anger. Journal of Psychology, In press. [Farsi] [ Links ].

Besharat, M. A. (2009b). Reliability and Validity of a short form of the Mental Health Inventory in an Iranian population. Forensic Medicine,In press. [Farsi] [ Links ].

Besharat, M. A. (2010). Factorial and cross-cultural validity of a Farsi version of the Anger Rumination Scale. Psychological Reports, In press. [ Links ]

Besharat, M. A. & Hoseini, S. A. (2009). Anger and aggression in sport. Research in Sport Science, In press. [Farsi] [ Links ].

Besharat, M. A., Hoseini, S. A., Mohammad Mehr, R. & Azizi, K. (2009). Reliability, Validity and factorial analysis of the Anger Rumination Scale. Research in Educational Systems, In press. [Farsi] [ Links ].

Besharat, M. A. & Mohammad Mehr, R. (2009). Psychometric evaluation of Anger Rumination Scale. Nursing and Midwifery Quarterly, 65, 36-43. [Farsi] [ Links ].

Bishop, G. D., Ngau, F. & Pek, J. (2008). Domain-specific asessment of anger expression and ambulatory blood pressure. Personality and Individual Differences, 44, 1726-1737. [ Links ]

Bongard, S. & Al'Absi, M. (2005). Domain-specific anger expression and blood pressure in an occupational setting. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 58, 43-49. [ Links ]

Bushman, B. J. (2002). Does venting anger feed or extinguish the flame? Catharsis, rumination, distraction, anger and aggressive responding. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 724-731. [ Links ]

Bushman, B. J., Baumeister, R. F. & Philips, C. M. (2001). Do people aggress to improve their mood? Catharsis beliefs, affect regulation opportunity and aggressive responding. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 17-32. [ Links ]

Deffenbacher, J. L. (1999). Cognitive-behavioral conceptualization and treatment of anger. Journal of Clinical Psychology/In Session: Psychotherapy in Practice, 55, 295-309. [ Links ]

Duckro, P. N., Chibnall, M. S. & Tomazic, T. J. (1995). Anger, depression, and disability: a path analysis of relationships in a sample of chronic postraumatic headache patients. Headache, 35, 7-9. [ Links ]

Everson, S. A., Goldberg, D. E., Kaplan, G. A., Julkunen, J. & Salonen, J. T. (1998). Anger expression and incident hypertension. Psychosomatic Medicine, 60, 730-735. [ Links ]

Everson, S. A., Kauhanen, J., Kaplan, G. A., Goldberg, D. E., Julkunen, J., Tuomilehto, J. & Salonen, J. T. (1997). Hostility and increased risk of mortality and acute myocardial infarction: the mediating role of behavior risk factors. American Journal of Epidemiology, 146, 142-152. [ Links ]

Fava, M., Nierenberg, A. A., Quitkin, F. M., Zisook, S., Pearlstein, T., Stone, A. & Rosenbaum, J. F. (1997). A preliminary study on the efficiency of sertraline and imipramine on anger attacks in atypical depression and dysthymia. Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 33, 101-103. [ Links ]

Fava, M. & Rosenbaum, J. F. (1999). Anger attacks in patients with depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 60 (Suppl. 15), 21-24. [ Links ]

Friedman, H. S. & Booth-kewley, S. (1987). The "disease-prone personality": a meta-analytic view of the construct. American Psychologist, 42, 539-555. [ Links ]

Frijda, N. (1986). The emotions. New York. Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Gallagher, J. E. J., Yarnell, J. W. G., Sweetnam, P. M., Elwood, P. C. & Stansfeld, S. A. (1999). Anger and incident heart disease in the Caerphilly study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 61, 446-453. [ Links ]

Harburg, E., Gleiberman, L., Russel, M. & Cooper, M. L. (1991). Anger-coping styles and blood pressure in Black and White males: Buffalo, New York. Psychosomatic Medicine, 53, 153-164. [ Links ]

Harburg, E., Julius, M., Kaciroti, N., Gleiberman, L. & Schork, M. A. (2003). Expressive/suppressive anger-coping responses, gender, and types of mortality: a 17-year follow-up Tecumseh, Michigan, 1971-1988. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65, 588-597. [ Links ]

Hogan, B. E. & Linden, W. (2005). Curvilinear relationships of expressed anger and blood pressur in women but not in men: evidence from two samples. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 59, 97-102. [ Links ]

Jorgersen, R. S., Johnson, B. T., Kolodziej, M. E. & Schreer, G. E. (1996). Elevated blood pressure and personality: a meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 120, 293-320. [ Links ]

Just, N. & Alloy, L. B. (1997). The response styles theory of depression: tests and extensions of the theory. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106, 221-229. [ Links ]

Kassinove, H. & Sukhodolsky, D. G. (1995). Anger disorders: Science, practice, and common sense issues. In Kassinove, H. (Ed.), Anger disorders: Definition, diagnosis, and treatment (pp. 1-26). Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

Kuehner, C. & Weber, I. (1999). Responses to depression in unipolar depressed patients: an investigation of Nolen-hoeksema's response styles theory. Psychological Medicine, 29, 1323-1333. [ Links ]

Langlois, R., Freeston, M. H. & Ladouceur, R. (2000a). Differences and similarities between obsessive intrusive thoughts and worry in a non-clinical population: Study 1. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38, 157-173. [ Links ]

Langlois, R., Freeston, M. H. & Ladouceur, R. (2000b). Differences and similarities between obsessive intrusive thoughts and worry in a non-clinical population: Study 2. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38, 175-189. [ Links ]

Lyubomirsky, S. & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1995). Effects of Self-Focused Rumination on Negative Thinking and Interpersonal Problem Solving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 6, 176-190. [ Links ]

Manne, S. & Schnoll, R. (2001). Measuring cancer patients' psychological distress and well-being: a factor analytic assessment of the Mental Health Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 13, 99-109. [ Links ]

Materazzo, F., Cathcart, S. & Pritchard, D. (2000). Anger, depression, and coping interactions in headache activity and adjustment: a controlled study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 49, 69-75. [ Links ]

Maxwell, J. P., Sukhodolsky, D. G., Chow, C. C. F. & Wong, C. F.C. (2005). Anger rumination in Hong Kong and Great Britain: Validation of the scale and a cross-cultural comparison. Personality and Individual Differences, 39, 1147-1157. [ Links ]

Mendesde Leon, C. F. M. (1992). Anger and impatience/irritability in patients of low socioeconomic status with acute coronary heart disease. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15, 273-284. [ Links ]

Moreno, J. K., Fuhriman, A. & Selby, M. J. (1993). Measurement of hostility, anger, and depression in depressed and nondepressed subjects. Journal of Personality Assessment, 61, 511-523. [ Links ]

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to Depression and Their Effects on the Duration of Depressive Episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100,569-582. [ Links ]

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depression in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 504-511. [ Links ]

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Parker, L. E. & Larson, J. (1994). Ruminative coping with depressed mood following loss. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 92-104. [ Links ]

Oatley, K. (1992). Best laid schemes: The psychology of emotions. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Painuly, N., Sharan, P. & Mattoo, S. K. (2005). Relationship of anger and anger attacks with depression: a brief review. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 255, 215-222. [ Links ]

Painuly, N., Sharan, P. & Mattoo, S. K. (2007). Antecedents, concomitants and consequences of anger attacks in depression. Psychiatry Research, 153, 39-45. [ Links ]

Riley, W. T., Treiber, F. A.& Woods, M. G. (1989). Anger and hostility in depression. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 177, 668-674. [ Links ]

Robbins, P. R. & Tanck, R. H. (1997). Anger and depressed affect: interindividual and intraindividual perspectives. Journal of Psychology, 131, 489-500. [ Links ]

Roberts, J. E., Gilboa, E. & Gotlib, I. H. (1998). Ruminative response style and vulnerability to episodes of dysphoria: gender, neuroticism, and episode duration. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 22, 401-423. [ Links ]

Rusting, C. L. & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1998). Regulating responses to anger: Effects of rumination and distraction on angry mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 790-803. [ Links ]

Siegman, A. W., Townsend, S. T., Blumenthal, R. S., Sorkin, J. D. & Civelek, A. C. (1998). Dimensions of anger and CHD in men and women: self-ratings versus spouse ratings. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 21, 315-336. [ Links ]

Smith, T. W. & Ruiz, J. M. (2002). Psychosocial influences on the development and course of coronary heart disease: current status and implications for research and practice. Journal of Consultant and Clinical Psychology, 70, 548-568. [ Links ]

Spicer, J. & Chamberlin, K. (1996). Cynical hostility, anger, and resting blood pressure. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 40, 359-368. [ Links ]

Spielberger, C. D. (1988). Manual for the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [ Links ]

Spielberger, C. D., Crane, R. S., Kearnes, W. D., Pellegrin, K. L. & Rickman, R. L. (1991). Anger and anxiety in essectial hypertension. In Spielberger, C. D., Sarason, I. G., Kulcsar, Z. & Van Heck, G. L. (Eds.), Stress and emotion: anxiety, anger and curiosity (pp. 265-279). New York: Hemisphere, Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

Spierings, E. L. H. & van Hoof, M. J. (1996). Anxiety and depression in chronic headache sufferers. Headache Quarterly, 7, 235-238. [ Links ]

Sukhodolsky, D. G., Golub, A. & Cromwell, E. N. (2001). Development and validation of the anger rumination scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 31, 689-700. [ Links ]

Suls, J., Wan, C. K. & Costa, P. T. (1995). Relationship of trait anger to resting blood pressure: a meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 14, 444-456. [ Links ]

Thomas, S. P., Groer, M., Davis, M., Droppleman, P., Mozingo, J. & Pierce, M. (2000). Anger and cancer. Cancer Nursing, 23, 344-349. [ Links ]

Troisi, A. & D'Argenio, A. (2004). The relationship between anger and depression in a clinical sample of young men: the role of insecure attachement. Journal of Affective Disorders, 79, 269-272. [ Links ]

Veit, C. T. & Ware, J. E. (1983). The structure of psychological distress and well-being in general population. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51, 730-742. [ Links ]

Watkins, E. (2004). Appraisals and strategies associated with rumination and worry. Personality and Individual Differences, 37, 679-694. [ Links ]

Wenzlaff, R. M. & Wegner, D. M. (2000). Thought suppression. Annual Review of Psychology, 51, 59-91. [ Links ]