Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

International Journal of Psychological Research

Print version ISSN 2011-2084

int.j.psychol.res. vol.5 no.2 Medellín July/Dec. 2012

Researh article

The influence of optimism and socioeconomic characteristics on leadership practices

La influencia del optimismo y las características socioeconómicas en las prácticas de liderazgo

Fernando Juárez*,a, Francoise Contrerasa

a Facultad de Administración, Administración de Empresas, Universidad del Rosario, Bogotá, Colombia.

* Fernando Juárez, Universidad del Rosario, Facultad de Administración, Administración de Empresas, Bogotá, Colombia, Calle 14, No. 4-61, Email: fernando.juarez@urosario.edu.co.

Recibido/Received: Septiembre 13 de 2012. Revisado/Revised: Octubre 04 de 2012. Aceptado/Accepted: Octubre 16 de 2012.

ABSTRACT

The role of optimism and socioeconomic characteristics of managers on leadership practices in small enterprises, in Bogotá, Colombia, was determined. Ninety managers completed the Leadership Practices Inventory and The Revised Life Orientation Test, as well as they provided information about personal and business socio-economic characteristics. Association measures between socio-economic and optimism variables with the Leadership Practices Inventory were taken. Besides, by Chi square test, Mann-Whitney's U and Kruskal-Wallis tests, they were determined socioeconomic differences in leadership styles, and, by a structural equation model, the effect of age, gender, marital status, socioeconomic status, number of employees of the company, economic sector, and optimism on leadership practices was analyzed. Only optimism and number of employees showed to be significant.

Key Words: Optimism, socioeconomic, leadership, transformational-transactional, small enterprises.

RESUMEN

Se evaluó el rol del optimismo y de las características socioeconómicas de los gerentes en sus prácticas de liderazgo en pequeñas empresas en Bogotá, Colombia. Noventa gerentes respondieron el Inventario de Prácticas de Liderazgo y el Test de Orientación de la Vida Revisado, proporcionando información sobre las características socioeconómicas individuales y de la empresa. Se tomaron medidas de asociación entre las variables socioeconómicas y el optimismo, con el Inventario de Prácticas de Liderazgo. Se realizaron pruebas de Chi cuadrado, U de Mann-Whitney y Kruskal-Wallis para determinar las diferencias socioeconómicas en liderazgo. Mediante un modelo de ecuaciones estructurales, se observó el efecto de la edad, el género, el estado civil, el estatus socioeconómico, el número de empleados de la compañía, el sector económico y el optimismo en las prácticas de liderazgo. Únicamente el optimismo y el número de empleados resultaron significativos.

Palabras Clave: Optimismo, socioeconómico, liderazgo, transformacional-transaccional, pequeña empresa.

1. INTRODUCTION

Leaders must encourage employee skills and increase creativity (Perdomo & Prieto, 2009), as the competitive sustainability of a company depends on human and social capital management, where leadership has a prominent role (Schneider, 2002). Leadership might have a positive effect overtaking the factors that threaten the survival of organizations. Some of those factors are managers' resistance to technological changes, poor strategic thinking to move on new challenges and a lack of business associations (Sanchez, Osorio, & Baena, 2007).

In high variability contexts and chaotic economic sectors, like that in Colombia, few companies maintain a healthy position (see Juárez, 2010a, 2010b, 2011), and identifying the manager's leadership practices, become relevant. Small and Medium Enterprises (SME's) are about 90% of all of the companies in the country (Aguirre, Pachón, Rodriguez, & Morales, 2006) and create 73% of employment and 53% of the gross domestic product (Rodríguez, 2003). Leader management practices can contribute to the sustainability of these companies.

Transformational and transactional model conceptualizes leadership as behavior (van Eeden, Cilliers, & van Deventer, 2008). Transformational leadership (Bass & Avolio, 1994), according to Bass, is widespread in society (Molero, 1995) and it is a way to rename charismatic leadership (Bass, 1985), or includes some characteristics of thereof, such as idealized influence and inspirational motivation (Bono & Llies, 2006). Although charismatic leadership, as characterized by Conger and Kanungo (1998), shows a high convergence validity with transformational leadership, they also show divergences, for example in their impact on profit (Rowold & Heinitz, 2007). The charismatic leader creates a positive vision of the future (Bass, 1985; Cicero & Pierro, 2007) and have an impact on the emotional climate of the team (Hernández, Araya, García, & González, 2009), due to participation and expressiveness (Friedman & Riggio, 1981), positive information processing (Ashkanasy & Tse, 2000) and expectations conveying (Fredrickson, 2003).

Transformational leaders appropriately cope with challenges and globalization, promoting adaptation (Howell & Higgens, 1990), participatory decision-making (Bass, 1997), openness to change, concentration on the group and organization interests (Krishnan, 2001; Sosik, 2005), and international negotiation achievements (Rosenzweig, 1998). Their characteristics are innovation, negotiation strategies, responsibility, persistency (Bass, 1997; Bass & Avolio, 1994), to give information, advice, support and encouragement to workers, increasing motivation and performance (Bass, 1997). They bring about outstanding achievement (Bass, 1985), becoming a standard to values and ethic (Bass & Riggio, 2006) and their vision results in feelings and inspiration in followers (Ross & Offermann, 1997; Wofford, Goodwin, & Whittington, 1998).

Transactional leader rewards or punishes according to performance (Lupano & Castro, 2005) and comprises a process of exchange, a transaction in which the leader clarifies expected results and what the followers should do; later on, leader will reward or penalize followers, according to their performance. Transactional leaders tend to closely monitories the activities of subordinates, to avoid errors or deviations from procedures and standards (Bass & Riggio, 2006). This leadership style can lead to satisfaction and employee performance; however, sometimes, it does not explain why some leaders produce extraordinary effects on the attitudes, beliefs and values of their followers (Molero, Recio, & Cuadrado, 2010). Nevertheless, efficacy is a characteristic of this leadership style, as it is usually aligned with business objectives. Transactional leaders operate within a system or culture, they try to satisfy the current needs of followers and pay attention to deviations and irregularities, taking actions to make corrections (Thépot, 2008).

Socioeconomic characteristics influence leadership. In this sense, leader activity increases along time to reach a peak in the middle age and then declines (Schubert, 1988); however, age seems not to have an effect on activities to be performed by a leader, yet older leaders have less need for relationships (Gilbert, Collins, & Brenner, 1990).In transformational leadership, oldest age and most educated people are more likely to provide broad guidance and few instructions, with an improved ability to listen to opinions and suggestions of subordinates (Ekaterini, 2010). On the other hand, gender does not settle differences among leadership styles, although it does among their tactics of influence, but the association of gender with education results in a reduction of these differences, as education gets higher (Barbuto, Fritz, Matkin, & Marx, 2007).

Leaders have an optimistic vision of the future (Bono & Llies, 2006). The concept of optimism bases on attribution theory, by Seligman (1998), who defines optimists as those who have stable, global and internal attributions about positive events, and unstable, external attributions about adverse events.

However, optimism, also involves a realistic assessment of what can or cannot be achieved in a situation (Schneider, 2001), along with a positive result perspective or attribution of events, positive emotions, motivation (Luthans, 2002) and persistency (Scheier & Carver, 1993). All these features are characteristics of transformational leaders (Chemers, Watson & May, 2000; George, 2000; Wunderley, Reddy, & Dember, 1998).

Optimism is a predictor of psychological adjustment (Brissette, Scheier, & Carver, 2002) and subjective well-being (Chang, 1998; Day & Maltby, 2003). Optimists experience few depressive symptoms when using a problem-focused or emotion-focused coping (Chico, 2002; Scheier & Carver, 1992). Whereas they have relatively stable tendencies, use problem-focused coping strategies, reframe the situation in a favorable way, and have an appropriate emotional response; pessimists, when they encounter problems, react with denial and no goals (Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 1994; Peterson & Bossio, 1991). Optimists possess skills to carry prosocial relationships (Popper, Amit, Gal, Mishkal-Sinai, & Lisak, 2004) and communicate and inspire employees (Mumford & Strange, 2002). Dispositional optimism is a widespread and stable expectation that future experiences will be more favorable than unfavorable (Scheier & Carver, 1985); besides, dispositional optimism, as measured by the Life Orientation Test (LOT) (Scheier & Carver, 1993), showed small cultural differences across 22 countries (Fischer & Chalmers, 2008), making this concept universal.

Most influential leaders exhibit an orientation toward the future, in their words, decisions and behaviors (Berson, Shamir, Avolio, & Popper, 2001) and findings show differences between leaders and non-leaders in optimism, considered as a proactive attitude and self-confidence (internal locus of control, low trait anxiety, and self-efficacy) (Popper, et al., 2004). Also, optimism associates to characteristics of leadership, as measured by Leadership Practices Inventory (Wunderley, et al., 1998), a mediator variable, along with anger, among leadership style, self-esteem and organizational commitment (McColl-Kennedy & Anderson, 2000), or between servant leadership and commitment to change (Kool & van Dierendonck, 2012). Optimism is also studied in relation to performance, along with, leadership efficacy (Chemers, at al., 2000), excellence (Chernin, 2002), or applied to the entire organization (organizational optimism) (Gabris, Marlin, & Ihrke, 1998).

However, association of optimism with transformational and transactional leadership practices has not been clearly identified. More specifically, although optimism can be a consequence of leadership style, or a mediator variable among leadership and other processes and dimensions, or even it associates to leadership, no research targets the issue of the influence of optimism on leadership style.

Based on the foregoing, this exploratory research aims to determine the role of optimism in transformational and transactional leadership practices of small enterprises managers, based on the hypothesis that such influence exists. Also, it tests the hypothesis of the influence of the individual and company socioeconomic characteristics on the style of leadership.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants

Participants were 90 managers (67.8% women and 32.2% men) in small enterprises, with an average age of 33.64 years. Their activity locates in different sectors of the economy (industrial, trade and services), in the city of Bogotá, Colombia. Participants were those available and willing to cooperate.

2.2. Materials

Leadership Practices Inventory (LPI). Developed by Kouzes and Posner (1988, 2003), the purpose of this inventory is to evaluate five leadership behaviors: 1) to challenge the processes and extend the risks, 2) to inspire a shared vision 3), to enable others to act, 4) to model the way, and 5) to encourage the heart. The first four are transformational leadership practices, while the last one is a transactional practice. Robles, de la Garza and Medina (2008) adapted this inventory to Spanish population, using a first adaptation by Mendoza (2005). The Likert-type scale comprises 30 items with a five-point response option. The Cronbach's alpha, for the entire scale, is over .70; for each subscale, it is as follows: a) to challenge the process (.72); b) to inspire a shared vision (.80); c) to enable others to act (.76), d) to model the way (.83); and e) to encourage the heart (.75) (Robles, et al., 2008).

Revised Life Orientation Test (LOT). This survey comprises ten items with a five-point response option and assesses the dispositional optimism or expectations of individuals about how favorable the results could be in the future. It includes six significant items, and four neutral, showing an internal consistency of .78 and a correlation of .95 with the large original version of thereof, the reliability index is .67 (Scheier, et al., 1994). Psychometric properties of the questionnaire, in Spanish-speaking population, showed a reliability coefficient of .68, in a sample of university students (Ferrando, Chico, & Tous, 2002).

Socioeconomic characteristics. Participants gave information about age, gender, marital status and socioeconomic status. Socioeconomic status is the participants' standard of living, according to the classification of the place where they live, made by the mayor's office of the city. In Colombia, it ranks from 1 (Low standard of living) to 6 (High standard of living). Company information about the number of employees and economic sector of its activity was also collected.

2.3. Procedure

Participants signed up an informed consent, before distributing the two surveys. Participation was voluntary and anonymous and they received no incentives for taking part in the research. The responding to surveys was in groups of 20 people, in average. Completion of the surveys took about 30 minutes per group.

3. RESULTS

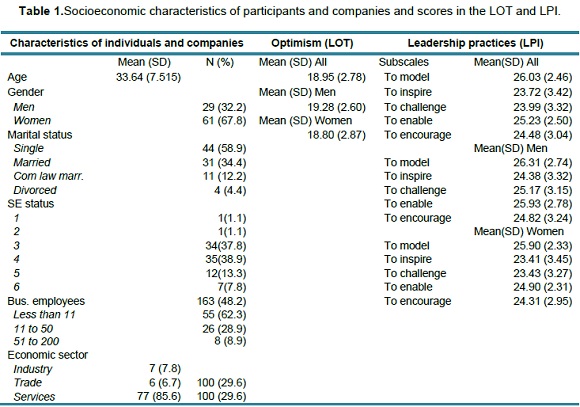

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants; most of them were women (n = 61, 67.8%), with an average age of 33.64 years, singles (n = 44; 58.9%) or married (n = 31; 34.4%). Participants had a median socioeconomic status of 3 (n = 34; 37.8%) and 4 (n = 35; 38.9%), and they labored as managers in small companies of the service sector (n = 77; 85.6%), which had from 11 to 50 employees (n = 26; 28.9%).

A nonparametric Chi square (χ2) test on categorical variables, checked for even distribution of categories in the sample; this test assesses whether categories have the same number of participants within them. Differences were significant for gender (χ2 = 11.378; p< .01), marital status (χ2 = 44.844; p< .01), company employees (χ2 = 39.200; p< .01), and business economic sector (χ2 = 110.467; p< .01). Therefore, the distribution of participants along these categories is significant and not random. Continuous variables were not normally distributed, and a nonparametric Kolmogorov-Smirnoff test drew a nonsignificant result (p> .05) for age, optimism and all of the leadership practices.

As Table 1 illustrates, there is a high score in dispositional optimism (mean of 18.95 out of 24, for all participants), as well as in the LPI subscales, with a mean ranking from 23.72 (to inspire) to 26.03 (to model), out of 30, for all participants. Men had higher scores than women in optimism in LPI subscales; however, the profile of the scores along the subscales is the same for men and women.

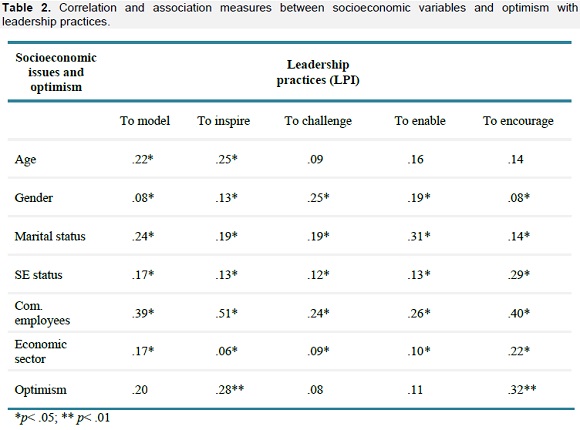

Based on data rank, Spearman's rho (ρ) showed the correlation between age and optimism, with every LPI practice (Table 2). The age of participants correlated with Modeling (ρ = .22; p< .05) and Inspiring (ρ = .25; p< .05) while optimism significantly correlated with Inspiring (ρ = .28; p< .01) and Encouraging (ρ = .32; p< .01).

Associations between categorical socioeconomic variables and leadership practices were determined by Eta (η) coefficient, which is suitable for categorical and interval data (Table 2). The highest η was for company employees with all of the leadership practices, while the rest of the socioeconomic variables had some few large associations, spread along the leadership practices. This association measure provides a significant coefficient (p = .04), by bootstrapping, for the confidence interval.

Another way to look at the effect of the socioeconomic variables on the practices of leadership (LPI) is considering these practices as dependent variables, while optimism and socioeconomic characteristics are independent variables. Accordingly, it can be tested whether categories of every socioeconomic variable impose differences in the LPI subscales. Mann-Whitney's U and Kruskal-Wallis tests are appropriate statistical procedures for ordinal or categorical data. Mann-Whitney's U test allows for two groups and gives a Z to assess its significant differences, while Kruskal-Wallis test allows for more than two groups and gives a χ2 as a comparison measure; both of them use the rank of the data. Categorical variables divide the sample into two groups, e.g. gender, or more than two groups, e.g. marital status, and continuous data are not normally distributed, so these tests are appropriate to determine whether leadership practice scores show an uneven distribution, along the categories of each socioeconomic variable. In case they do, it would mean that having a specific socioeconomic category, in a variable, would imply to have a higher probability of showing a certain leadership practice.

By Mann-Whitney's U test, the contribution of gender was found significant only on the dimension of Challenging (Z = -2.295; p< .05). By Kruskal-Wallis test, it was observed that the contribution of marital status was only significant in the dimension of Enabling (χ2 = 8.916; p< .05) and that the number of company employees was significant in the dimensions of Modelling (χ2 = 15.269; p< .01), Inspiring (χ2 = 25.035; p< .01), Enabling (χ2 = 6.716; p< .05) and Encouraging (χ2 = 16.007; p< .01); no other variable had statistical significance. According to this, the number of company employees is the most consistent in creating differences in the scores of leadership practices.

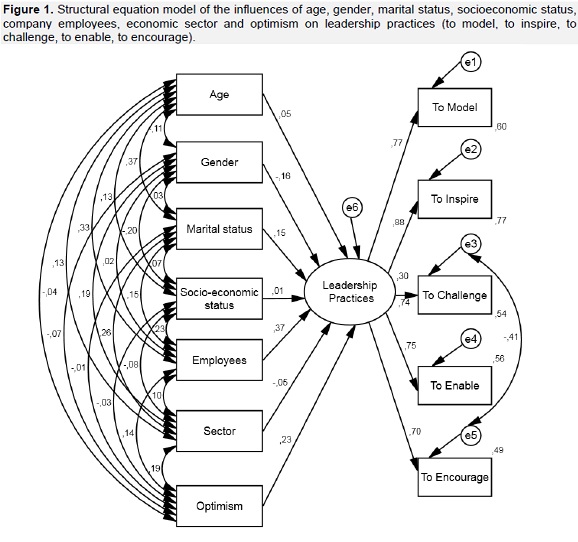

Otherwise, the influence of optimism and age, as long as that of the socioeconomic variables, were tested by a structural equation model, which allows for determining the combined effect of all of these variables. Continuous variables were normalized before entering the model. The model depicts in Figure 1.

The model was significant (χ2= 42.370; p =.079) and showed a proper goodness of fit (χ2/g.l. = 1.32; RMR = .037; GFI = .927; AGFI = .822; CFI = .963). The model brings the influences of the independent variables, the correlations among them and all of the leadership practices, as dependent variables, together. A latent variable (Leadership practices) allows for grouping the five LPI subscales. This is a multiple regression model with correlated-independent variables (exogenous) and several dependent variables (endogenous).

In the figure, numbers next to single arrow lines show standardized coefficients for the variables. The LPI subscales have a high score in their relationship to leadership practices, so this latent construct is a fairly representation of the five subscales. The most influential variables on leadership practices are company employees (.37) and optimism (.23); these variables have a strong influence on LPI subscales through leadership practice latent variable.

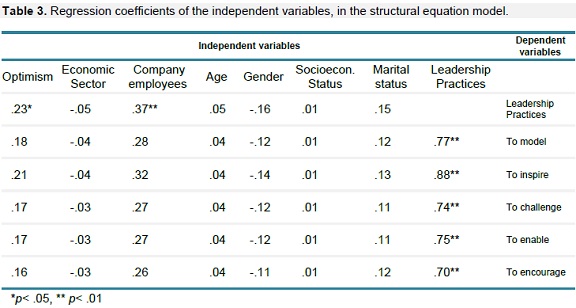

In structural equation models, direct and indirect effects on dependent variables exist, but they can be thought as different influences put together in a linear regression. Table 3 shows the combined standardized effect of all these effects on leadership practices. The coefficients of the independent variables are the B coefficients in a regression model.

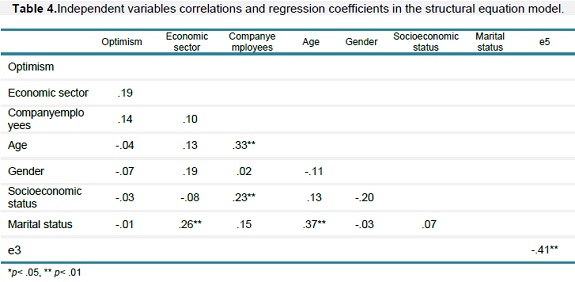

In Table 3, the coefficients show the path of influence on LPI subscales or leadership practice latent variable. The model tests for the regression coefficients depicted in Figure 1. The most influential and significant variable on each LPI subscale is leadership practices, as this variable emerges from these subscales. The second most influential group of variables are optimism and company employees, and the third group is gender and marital status; gender with a negative sign, meaning that women are to give lower scores in Leadership practices than men. The other variables have a negligible amount of influence. However, it must be taken into account that, from the coefficients tested in the model, only optimism and company employees showed to have a significant influence on leadership practices. Table 4 shows the coefficients of correlations for the independent variables.

This table shows correlation coefficients; significance coefficient (p) was obtained for covariances, but their standardized coefficient is correlation, showed in the table. Most of the correlations coefficients of the independent variables are not significant. Positive and significant correlations exist between marital status and economic sector (.26), marital status and age (.37), socioeconomic status and company employees (.23), and age and company employees (.33), while a negative and significant correlation exists between e3 and e5 (-.41), which are error residual variables. Figure 1 shows these correlations.

4. DISCUSSION

According to results, managers of small enterprises in Colombia have strong leadership skills, combined with a healthy dose of optimism. Positive emotions (associated to optimism) are a characteristic of transformational leaders (see Bono & Llies, 2006); however, data show that optimism clearly influences all of the subscales of leadership practices, as showed in Table 3. This agrees with the favorable results that individuals obtain in the functions they perform (Schneider, 2001), and with the optimistic focus on problems rather than emotion (Chico, 2002; Scheier & Carver, 1992). This focus on problem solution, explains why optimism relates to transactional leadership because optimism, as a disposition, also has to do with the activities undertook at now. Despite some negative results, regarding performance of transactional leadership (Ogbonna & Harris, 2000), the focus on charisma could leave out the process to reach a vision (Angel, 2009). Charismatic and transformational leadership can integrate with transactional leadership resulting in superior performance and, at the same time, acknowledging business structure. In this research, the subscale related to transactional leadership (To encourage), have similar scores to those of Transformational leadership (To model, To inspire, To challenge, To enable), so managers do not forget the transactional view and take advantage of it.

The socioeconomic variables of managers could affect their practices of leadership. For instance, socioeconomic similarity is the main factor influencing the entry to leadership in some communities (Payne, 1972), but results show that none of these individual variables had a significant effect on the leadership practices. This is in contrast with the belief of exceptional efficiency of the leader, at an old age, in the handling of certain situations (Ekaterini, 2010). Results make it be stated that leadership skills could be achieved by experience and training, and not merely by age. In community leadership, training and not age was essential to acquire a leader role (Schultz & Galbraith, 1993); however, leadership activity reaches a peak in the middle age (Schubert, 1988). According to this, a sample with a more range of age would be needed to check whether that influence of age takes place over 40 years old, which is the limit imposed in this research by the standard deviation.

Another compelling issue is gender; women are well represented in this research (67.8%), what could be in accordance with the reported figure of 64% of companies having at least one woman in director positions (Matsa & Miller, 2011). However, women are more common in leadership among senior adult (Schultz & Galbraith, 1993). Female leadership exists (see Matsa & Miller, 2011), and results show that gender imposed differences on the LPI subscale of Challenging; but when analyzed within a structural equation model with all of the variables together, other variables shadow gender, and so it was not significant. On the other hand, despite men scored higher than women, the profile along the subscales is the same, showing no differences in leadership style, as stated (see Barbuto, et al., 2007).

This is in contrast with that stereotyped view of women as communal and men as agentic (Ridgeway, 2001) or with the characteristics of leadership attributed to men or women (Lupano & Castro, 2008a, 2008b). If they were that different, their practices of leadership should also be different, but, as they have a similar profile, it means their leadership practices are similar, except for intensity. This can have to do with expectations equality (Ridgeway, 2001), what poses that performance of men and women do not relate to gender but to stereotyped expectations based on gender. However, it may be needed to change the nature of the organization, when confronting with inclusion and equity issues (Narayan, 2009); besides, the culture influences on the position of women as leaders (Rowley, 2010) must be taken into account.

Regarding marital status, although it had some associations with leadership practices (range from .14 to .31, Table 2), when entered into an all-variables-combined model, marital status showed no relevance on leadership practices (Table 3).

Socioeconomic status is a variable influencing leadership (Dhuey & Lipscomb, 2008), and it is relevant, along with leader position, for example to produce a high-stage moral reasoning (Lamport, Galaz-Fontes, & Morse, 2006). However, results demonstrated that socioeconomic status had small associations with LPI subscales (Table 2), imposed no differences on leadership practices, and had no significance when entered into the structural equation model. Finally, other issues are economic sector and number of employees of the company. While economic sector had a small association with leadership practices and no influence on them, the number of company employees strongly influenced all of the leadership practices, as demonstrated by association measures (Table 2), comparison measures, and a structural equation model. According to this, when the number of employees is large, the leadership practices increases. This could be in accordance with the fact that the larger the company the greater it achieves in human resource management effectiveness and satisfaction (Schneider, 2002). Given the importance of small and medium enterprises in Colombia (Aguirre, et al., 2006), this helps to explain why some of these companies do not survive in so complex environment as that of the Colombian market. According to this, it seems that small companies would need to improve their leadership practices to be more competitive.

Although transformational leadership associates to successful companies (Jandaghi, Zarei, & Farjami, 2009), it seems a need to take into account the size of the company, as the number of employees get larger, the leadership practice scores increase. The role of leadership is of considerable importance in medium-sized enterprise (Tonge, Larsen, & Ito, 1998), and so it should be in small enterprise, as this research showed, regarding transactional and transformational leadership.

5. CONCLUSIONS

According to aforementioned, this research aimed to understand the influence of optimism as a disposition, along with other economic characteristics, on transformational and transactional leadership practices. Based on results, optimism along with company number of employees, are the relevant variables influencing both transformational and transactional leadership practices, which confirms the hypothesis of influence of optimism and partly confirm the hypothesis of socioeconomic characteristic influence.

Another conclusion is that given the existing discussion about the preference for transformational or transactional leadership, it seems a need to provide a more comprehensive education and foster combined leadership. According to this, lack of education of the leaders who must provide support to new developments is a serious issue in creating barriers to advancement of practices (Johansson, Fogelberg-Dahm, & Wadensten, 2010).

Finally, a broader sample of economic sectors and small enterprises needs to be analyzed, to give more representative results.

6. REFERENCES

Aguirre, A. M., Pachón, L. N., Rodríguez, N. M., & Morales, P. A. (2006, noviembre). Entorno cultural, político y socioeconómico de la PYMES. Gestipolis.com. Available at http://www.gestiopolis.com/canales7/emp/entorno-cultural-politico-y-socioeconomico-de-las-pymes.htm. Access onJuly 25, 2010. [ Links ]

Angel, A. C. (2009). El precio del liderazgo carismático. Debates IESA, XIV(1), 62-64. [ Links ]

Ashkanasy, N. M. & Tse, B. (2000). Transformational leadership as management of emotions: A conceptual review. In Ashkanasy, N.M. & Hartel, C. E. (Eds.), Emotions in the workplace: Research, theory and practice (pp. 221-235). Westport CT; Quorum Books/Greenwald Publishing Group. [ Links ]

Barbuto Jr., J. E., Fritz, S. M., Matkin, G. S. & Marx, D. B. (2007). Effects of Gender, Education, and Age upon Leaders' Use of Influence Tactics and Full Range Leadership Behaviors. Sex Roles, 56, 71-83. [ Links ]

Bass, B.M. (1985). Leadership: Good, better, best. Organizational Dynamics, 3, 26-40. [ Links ]

Bass, B. M. (1997). Does the transactional-transformational leadership paradigm transcend organizational and national boundaries? American Psychologist, 52, 130-139. [ Links ]

Bass, B. M. & Avolio, B. J. (1994). Introduction. En Bass, B. M. & Avolio, B. J. (Eds.), Improving organizational effectiveness (pp. 1-9). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Bass, B. M., & Riggio, R. E. (2006). Transformational Leadership. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Berson, Y., Shamir, B., Avolio, B. J. & Popper, M. (2001). The relationship between vision strength, leadership style, and context. Leadership Quarterly, 12, 53-73. [ Links ]

Bono, J.E., & Llies, R. (2006). Charisma, positive emotions and mood contagion. The Leadership Quarterly, 17, 317-334. [ Links ]

Brissette, I., Scheier, M. F. & Carver, C. S. (2002). The role of optimism and social network development, coping, and psychological adjustment during a life transition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 102-111. [ Links ]

Chang, E. C. (1988). Does dispositional optimism moderate the relation between perceived stress and psychological well-being?: A preliminary investigation. Personality and Individual Differences, 25(2), 233-240. [ Links ]

Chemers, M. M., Watson, C. B., & May, S. T. (2000). Dispositional affects and leadership effectiveness: A comparison of self-esteem, optimism and efficacy. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 267-277. [ Links ]

Chernin, P. P. (2002). Creative Leadership Excellence is an expression of optimism. Executive Excellence, 193. [ Links ]

Chico, E. (2002). Optimismo disposicional como predictor de estrategias de afrontamiento. Psicothema,14, 544-550. [ Links ]

Cicero, L., & Pierro, A. (2007). Charismatic leadership and organizational outcomes: The mediating role of employees' work-group identification. International Joumal of Psychology, 42, 297-306. [ Links ]

Conger, J. A., & Kanungo, R. N. (1998). Charismatic Leadership. Thousand Oak: Sage. [ Links ]

Day, L., & Maltby, J. (2003). Belief in good luck and psychological well-being: The mediating role of optimism and irrational beliefs. Journal of Psychology,137, 99-112. [ Links ]

Dhuey, E. & Lipscomb, S. (2008). What makes a leader? Relative age and high school leadership. Economics of Education Review, 27, 173-183. [ Links ]

Ekaterini, G. (2010). The Impact of Leadership Styles on Four Variables of Executives Workforce. International Journal of Business and Management, 5, 3-16. [ Links ]

Ferrando, P., Chico, E. & Tous, J. (2002). Propiedades psicométricas del Test de Optimismo. Life Orientation Test. Psichotema, 14, 673-680. [ Links ]

Fischer, R. & Chalmers, A. (2008). Is optimism universal? A meta-analytical investigation of optimism levels across 22 nations. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(5), 378-382. [ Links ]

Fredrickson, B. (2003). The value of positive emotions. American Scientist, 91, 330-335. [ Links ]

Friedman, H. S. & Riggio, R. E. (1981). Effect of individual differences in nonverbal expressiveness on transmission of emotion. Journal of Non Verbal Behavior,6, 96-104. [ Links ]

George, J. M. (2000). Emotion and leadership: The role of emotional intelligence. Human Relations, 53, 1027-1055. [ Links ]

Gabris, G. T., Marlin, S. A. & Ihrke, D. M. (1988). The leadership enigma: toward a model of organizational optimism. Journal of Management History, 4(4), 334-349. [ Links ]

Gilbert, G. R., Collins, R. W. & Brenner, R. (1990). Age and Leadership Effectiveness: From the Perceptions of the Follower. Human Resource Management, 29(2), 187-196. [ Links ]

Hernández, A., Araya, C., Garcia, J. & Gonzalez, V. (2009). Leader charisma and affective team climate: The moderating role of the leader's influence and interaction. Psicothema, 21(4), 515-520. [ Links ]

Howell, J. M. & Higgens, C. A. (1990). Champions of technological innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35, 317-341. [ Links ]

Jandaghi, G. H., Zarei, H. & Farjami, A. (2009). Comparing Transformational Leadership in Successful and Unsuccessful Companies. International Journal of Social Sciences, 4(3), 211-216. [ Links ]

Johansson, B., Fogelberg-Dahm, M. & Wadensten, B. (2010). Evidence-based practice: the importance of education and leadership. Journal of Nursing Management, 18, 70-77. [ Links ]

Juárez, F. (2010a). Applying the theory of chaos and a complex model of health to establish relations among financial indicators. Procedia Computer Science, 3, 982-986. [ Links ]

Juárez, F. (2010b). Caos y salud en el sector económico de la salud en Colombia. International Journal of Psychological Research, 3(2), 29-33. [ Links ]

Juárez, F. (2011). Financial health and risk in the tourism sector in Colombia. International journal of mathematical models and methods in applied sciences, 4(5), 747-754. [ Links ]

Kool, M. & van Dierendonck, D. (2012). Servant leadership and commitment to change, the mediating role of justice and optimism. Journal Of Organizational Change Management, 25(3), 422-433. [ Links ]

Kouzes, J. & Posner, B. (1988). The Leadership Practices Inventory. San Diego, CA: Pfeiffer. [ Links ]

Kouzes, J. & Posner, B. (2003). The leadership Practices Inventory (LPI): Self Instrument. San Francisco: Jessey-Bass/ Pfeiffer. [ Links ]

Krishnan, V. R. (2001). Values Systems of Transformational Leaders.Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 22(3), 126-131. [ Links ]

Lamport, M., Galaz-Fontes, J. F. & Morse, S. J. (2006). Leadership, cross-cultural contact, socio-economic status, and formal operational reasoning about moral dilemmas among Mexican non-literate adults and high school students. Journal of Moral Education, 35(2), 247-267. [ Links ]

Lupano, M. L. & Castro, A. (2005). Estudios sobre el liderazgo: teoría y evaluación. Psicodebate, 6, 107-122. [ Links ]

Lupano, M. L. & Castro, A. (2008a). Liderazgo y género. Identificación de Prototipos de liderazgo efectivo. Perspectivas en Psicología, 5(1), 69-77. [ Links ]

Lupano, M. L. & Castro, A. (2008b). Prototipos de liderazgo masculino y femenino en población militar. Revista de Psicología, XXVI(2), 195-218. [ Links ]

Luthans, F. (2002). The need for and meaning of positive organizational behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 695-706. [ Links ]

Matsa, D. A. & Miller, A. R. (2011). Chipping away at the Glass Ceiling: Gender Spillovers in Corporate Leadership. American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, 101(3), 635-639. [ Links ]

McColl-Kennedy, J. R. & Anderson, R. B. (2000, August). Anger and optimism as mediators in the relationship between leadership style, organization-based self esteem and organizational commitment. In Ashkanasy, N. M., Hartel, Ch. E. J. & Zerbe, W. P. Conference Program and Abstracts. 2nd International Conference on Emotions and Organizational Life, Ryerson Polytechnic University, Toronto, Canada, (17-18). [ Links ]

Mendoza, M. (2005). Estudio diagnostico del perfil de liderazgo transformacional y transaccional de gerentes de ventas de una empresa farmacéutica a nivel nacional. Tesis de doctorado no publicada, ciencias económicas y administrativas. Tlaxcala: Universidad Autónoma de Tlaxcala. [ Links ]

Molero, F. (1995). El estudio del carisma y del liderazgo carismático en las ciencias sociales: una aproximación desde la Psicología Social. Revista de Psicología Social, 10, 43-60. [ Links ]

Molero, F., Recio, P. & Cuadrado, I. (2010). Liderazgo transformacional y liderazgo transaccional: un análisis de la estructura factorial del Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) en una muestra española. Psicothema, 22(3), 495-501. [ Links ]

Mumford, M. D. & Strange, J. M. (2002). Vision and mental models: The case of charismatic and ideological leadership. En Avolio, B. J. & Yammarino, F. J. (Eds.), Transformational and charismatic leadership: The road ahead (Monographs in Leadership and Management (pp. 109-142). New York: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Narayan, A. (2009). Gender Diversity and leadership Inclusion: The Keys to Workplace Success. Gender and Workplace Experience, 34(4), 102-106. [ Links ]

Ogbonna, E. & Harris, LL. C. (2000). Leadership style, organizational culture and performance: empirical evidence from UK companies. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 11(4), 766-788. [ Links ]

Payne, D. E. (1972). Socioeconomic Status and leadership selection in the Mormon Missionary System. Reviews of ReligiousResearch, 13(2), 118-125. [ Links ]

Perdomo, Y. & Prieto, R. (2009). El liderazgo como herramienta de competitividad para la gerencia del servicio. Revista Electrónica de Estudios Temáticos, 6, 20-35. [ Links ]

Peterson, C. & Bossio, L. (1991). Health and optimism. New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

Popper, M., Amit, K., Gal, R., Mishkal-Sinai, M. & Lisak, A. (2004). The Capacity to Lead: Major Psychological Differences Between Leaders and Nonleaders. Military Psychology, 16(4), 245-263. [ Links ]

Ridgeway, C. L. (2001). Gender, Status, and Leadership. Journal of Social Issues, 57(4), 637-655. [ Links ]

Robles, V. H., de la Garza, M. I. & Medina, J. M. (2008). El liderazgo de los gerentes de las PYMES de Tamaulipas, México, mediante el Inventario de Practicas de Liderazgo. Cuadernos de Administración, 21(37), 293-310. [ Links ]

Rodriguez, A. G. (2003). La realidad de la PYME Colombiana. Desafío para el desarrollo. Bogotá: Fotolito Colombia Preprensa Digital. [ Links ]

Rosenzweig, P. (1998). Managing the new global workforce: Fostering diversity, forging consistency. European Management Journal, 16, 644-652. [ Links ]

Ross, S. M. & Offermann, L. R. (1997). Transformational leaders: Measurement of personality attributes and work group performance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 1078-1086. [ Links ]

Rowley, S. (2010). Leadership Through A Gender Lens: How Cultural Environments and Theoretical Perspectives Interact with Gender. International Journal of Public Administration, 33, 81-87. [ Links ]

Rowold, J. & Heinitz, K. (2007). Transformational and charismatic leadership: Assessing the convergence, divergent and criterion validity of the MLQ and the CKS. The Leadership Quarterly, 18, 121-133. [ Links ]

Sánchez, J. J., Osorio, J. & Baena, E. (2007). Algunas aproximaciones al problema de financiamiento de las PYMES en Colombia [versión electrónica]. Scientia et Technica, 34, 321-324. [ Links ]

Scheier, M. F. & Carver, C. S. (1985). Optimism, coping and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology, 4, 219-247. [ Links ]

Scheier, M. F. & Carver, C. S. (1992). Effects of optimism on psychological and physical well-being: Theoretical overview and empirical update. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 16, 201-228. [ Links ]

Scheier, M. F. & Carver, C. S. (1993). On the power of positive thinking: The benefits of being optimistic. Current Directions in Psychological Sciences, 2, 26-30. [ Links ]

Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S. & Bridges, M. W. (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem: A Reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and social Psychology, 67(6), 1063-1078. [ Links ]

Schneider, S. I. (2001). In search of realistic optimism. American Psychologist, 56, 250-263. [ Links ]

Schneider, M. A. (2002). Stakeholder Model of Organizational leadership. Organization Science, 13, 209-220. [ Links ]

Schubert, J. N. (1988). Age and Active-Passive Leadership Style. The American Political Science Review, 82(3), 763-772. [ Links ]

Schultz, C. M. & Galbraith, M. W. (1993). Community Leadership Education for Older Adults: An Exploratory Study. Educational Gerontology, 19(6), 473-488. [ Links ]

Seligman, M. (1998). Learned optimism. New York: Pocket Books. [ Links ]

Sosik, J. J. (2005). The Role of Personal Values in the Charismatic Leadership of Corporate Managers: A Model and Preliminary Study. Leadership Quarterly, 16, 221-244. [ Links ]

Thépot, J. (2008). Leadership Styles and Organization: a Formal Analysis. Revue Sciences de Gestion, 68, 287-308. [ Links ]

Tonge, R., Larsen, P. C. & Ito, M. (1998). Strategic Leadership in Super-Growth Companies-A Re-appraisal. Long Range Planning, 31(6), 838-847. [ Links ]

Van Eeden, R., Cilliers, F. & van Deventer, V. (2008). Leadership styles and associated personality traits: support for the conceptualization of transactional and transformational leadership. South African Journal of Psychology, 38(2), 253-267. [ Links ]

Wofford, J. C., Goodwin, V. L., & Whittington, J. L. (1998). A field study of a cognitive approach to understanding transformational and transactional leadership. Leadership Quarterly, 9, 55-84. [ Links ]

Wunderley, L. J., Reddy, W. B., & Dember, W. N. (1998). Optimism and pessimism in business leaders. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28, 751-760. [ Links ]