Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

International Journal of Psychological Research

Print version ISSN 2011-2084

int.j.psychol.res. vol.6 no.1 Medellín Jan./June 2013

Mimicry and Honesty: People Give More Honest Responses to Their Mimicker

Imitación y honestidad: La gente es más sincera con su imitador

Nicolas Guéguen*,a

a Universite de Bretagne-Sud, Lorient, France

* Nicolas Guéguen, Université de Bretagne-Sud, UFR DSEG. Rue de la loi, 56000 Vannes. Email: nicolas.gueguen@univ-ubs.fr

Received: Febrero 3 de 2013 - Revised: Junio 15 de 2013 - Accepted: Junio 18 de 2013

ABSTRACT

Mimicry is generally associated with a positive perception of the mimicker. Our hypothesis stated that participants would become more honest in their responses to a survey administered by a mimicking interviewer. Students were invited to participate in a survey on their ecological behavior. During the first part of the survey, the 'experimental confederate' either mimicked their interlocutor or did not. It was found that participants declared less ecological behavior in their everyday life in the mimicry condition than in the non-mimicry condition.

Key Words: Mimicry, Survey response, Honesty.

RESUMEN

La imitación está generalmente asociada con una percepción positiva del imitador. Nuestra hipótesis consistía en que los participantes debían ser más sinceros en sus respuestas en una entrevista conducida por un entrevistador que los imitará. Algunos estudiantes fueron invitados a participar en una entrevista acerca de sus comportamientos ecológicos. Durante la primera parte de esta, el "cómplice experimental" imitaba a su interlocutor o no lo hacía. Se encontró que los participantes reportaron menos comportamientos ecológicos en su diario vivir en la condición de imitación que en el caso contrario.

Palabras Clave: Imitación, entrevista, respuesta, honestidad.

1. INTRODUCTION

Mimicry, also called the 'chameleon effect' (Chartrand & Bargh, 1999), refers to the unconscious imitation of postures, facial expressions, mannerisms and other verbal and nonverbal behaviors. Much of the research on this topic has studied the impact of mimicry on the perception of the mimicker.

Research has also found that mimicry is associated with a more positive evaluation of the mimicker. Chartrand and Bargh (1999, study 2) engaged participants in a task with a confederate who was instructed to either mimic the mannerism of the participant, or to exhibit neutral, nondescript mannerisms. Participants who were mimicked by the confederate subsequently reported a higher mean of liking for the confederate, and described their interaction with him/her as smoother as and more harmonious than those who were not mimicked. This result is congruent with previous work by Maurer and Tindall (1983), who found that when a counselor mimicked a client's arm and leg position, this mimicry enhanced the client's perception of the counselor's level of empathy compared to when the counselor did not mimic the client. Interacting in an immersive virtual reality with an embodied artificial agent mimicking our own behavior is sufficient to influence the agent's rating. In a recent experiment by Bailenson and Yee (2005), a virtual agent verbally presented a persuasive argument (a message advocating a campus security policy) to a participant. In half of the cases, the virtual agent mimicked the participant's head movements with a 4-second delay; for another group of participants, the agent mimicked the prerecorded movements of another participant. After the interaction, the participant indicated his/her agreement with the message delivered by the agent and gave his/her impression of the agent. It was found that the mimicking virtual agent was more persuasive, and received more positive trait ratings than non-mimickers.

If mimicry is associated with a greater liking for the mimickers and a greater feeling of affiliation, several studies have found that mimicry leads to enhance pro-social behavior toward the mimickers. Van Baaren, Holland, Steenaert and Van Knippenberg (2003) found in two experiments that mimicking the verbal behavior of customers in a restaurant increased the amount of the tips. In their first experiment, a waitress was instructed to mimic the verbal behavior of half of her customers by literally repeating their order. It was found that the waitress received significantly larger tips when she mimicked the patrons than when she did not. In a second experiment, it was found that compared to a baseline condition, mimicry was associated with a higher rate of tipping customers, and also with larger tips. Spontaneous helping behavior is also affected by mimicry. Van Baaren, Holland, Kawakami and Van Knippenberg (2004) mimicked the posture (position of the arms, of the legs…) of half of the participants in a task in which they were asked to evaluate various advertisements. The experimenter, who was seated in front of the participant, mimicked or not the participant's posture. When the task was concluded, the experimenter "accidentally" dropped six pens on the floor. It was found that participants in the mimicry condition picked up the pens more often (100 %) than participants in the non-mimicry condition (33 %). Behavioral mimicry can also facilitate the outcome of negotiations. In a recent study by Maddux, Mullen and Galinsky (2008), it was found that mimicry facilitated a negotiator's ability to uncover underlying compatible interests, and also increased the likelihood of closing a deal in a negotiation where a prima facie solution was not possible.

All above, these studies show that mimicry seems to enhance social relationships. For Lakin, Jefferis, Cheng and Chartrand (2003), the relationship between mimicry and liking or pro-social behavior could be explained in terms of human evolution. For these authors, mimicry may serve to foster relationships with others. This behavior could serve as "social glue", binding people together and creating harmonious relationships.

Given that mimicry is associated with greater attraction toward the mimicker, our hypothesis stated that individuals mimicked by an unknown interviewer would be more honest in their responses than individuals who were not mimicked. Indeed, it has been found that a positive judgment of an interviewer is associated with greater honesty in the participants' responses (Knapp, 2008).

2. METHOD

2.1. Participants

The participants were 40 male and 40 female students (aged between approximately 18 and 24 years) from the University of Bretagne-Sud in France, who approached when they were walking alone on various areas of the campus. They were randomly assigned to one of two experimental conditions (40 participants per condition)

2.2. Procedure

Four female students acted as interviewers in this experiment and were instructed to interview 20 participants (10 males and 10 females). They were not informed about the objective of the experiment and received no information about previous studies on mimicry. According to the group to which they had been randomly assigned, the interviewer, when approaching the student, was instructed either to mimic, or not, the participant. The interviewer would approach a student walking alone and say with a smile: 'Hello, I am conducting a survey on people's ecological behaviors in their everyday life. Would you be happy to answer 10 questions on this topic?' If the participant agreed, then the interviewer would begin to conduct her survey. The questionnaire was composed of two parts. The first one measured knowledge related to ecological matters and was used as a filler item in order to allow the interviewer to mimic the participant (e. g. 'Do you know how long it takes for chewing-gum/ a cigarette butt/a plastic bag/a can of soda to decompose?'). During this time, in the mimicking condition, the interviewer was instructed to mimic the participant's verbal behavior by literally repeating some of his or her words, verbal expressions or statements. For example, if the participant said 'Well… I think that it takes 3 years for a piece of chewing-gum to decompose', then the interviewer was instructed to say "Well… You think that it takes 3 years for a piece of chewing-gum to decompose'. The interviewer was also instructed to mimic some of the participant's nonverbal behavior. For example, if the participant touched or rubbed his/her face, then the interviewer was instructed to touch or to rub her face 2 or 3 seconds later.

We decided to limit the mimicry to non-verbal behaviors displayed by the participant on his/her face because previous studies on mimicry found that these behaviors are easy to spot, easy to replicate and that mimicking such behaviors is associated with effectiveness on social influence and positive perception of the mimicker (Chartrand & Bargh, 1999; Guéguen, Martin & Meineri, 2011). It has also been found that mimicking such behaviors is not associated with the participant's consciousness of mimicking in face to face interaction (Guéguen, 2009; Maddux et al., 2008).

In the non-mimicry condition, the interviewer was instructed to be careful not to mimic verbal expressions or, sentences or the nonverbal behavior of the participant. Apart from this difference in verbal and nonverbal behavior in the mimicry condition, the interviewers were instructed to attempt to act in the same way with the participant.

The interviewers were blinded about the hypothesis and were previously trained in a pre-test and in a role-playing situation in order to learn how to approach the participants and how to mimic them. In order to prevent possible behavioral changes with the interviewers in the two experimental conditions, they were discreetly observed by 2 male observers who were informed that half of the time, the interviewers were in one experimental condition whereas in the other half of the time, they were in a second one. They were instructed to evaluate in which condition the interviewer was by simply observing the interview and noting at the end the condition 1 or 2 on a form. The results of each observer were compared with the real experimental condition displayed. The analysis showed that neither the first observer nor the second one were able to distinguish the mimicry condition from the non-mimicry one.

Subsequently, the second part of the survey was administered and the interviewers, in the mimicry condition, were instructed to cease mimicking the participant. This part of the survey focused on six different participant's ecological behaviors (e.g.: 'Do you ever drop waste in the country side?' .or 'Do you switch off your heating when you open a window to air a room?').

For each question four propositions of responses appeared and were associated with a numerical code: 1 noted "No", 2 noted "sometimes", 3 noted "Yes" and 4 noted "All the time".

Example with one question: Do you switch off your heating when you open a window to air a room?'

- (1) No; (2) Sometimes; (3) Yes; (4)

All the time"

These questions were asked in order to measure the honesty of the responses given by the participant. A recent study conducted in France that focused on real ecological behaviors displayed by students showed that a majority of them wasted energy and were reluctant to sort their household waste for recycling (Girandola & Weiss, 2010). However, their attitudes toward ecology and energy consumption were extremely positive. Thus, we expected that our informants' responses would be more genuine in the mimicry condition and that participants would admit to failing to adopt all the preferred ecological behaviors.

3. RESULT

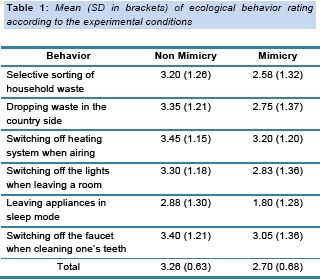

According to the Likert scale used to evaluate the participant's responses, a lower score reflected a lower level of ecological behavior admitted by the participant. The means of the six ecological behaviors measured are presented in ecological behaviors measured are presented in ecological behaviors measured are presented in Table 1.

In the mimicry condition, participants admitted less ecological behavior (M = 2.7; SD = 0.68) compared with a mean of 3.26 (SD = 0.63) in the non-mimicry control condition. With the score of the 6 dependent variables, a 2 (gender of the participants) × 2 (experimental conditions) Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) was performed. Only a main effect of the experimental condition was found F (6, 73) = 2.86, p = .02, ηp² = .19).

4. DISCUSSION

The results presented here reveal that participants reported performing less ecological behavior in their everyday life in the mimicry condition than in the non-mimicry condition. Given that recent behavioral studies conducted in France amongst this population (young people from 18 to 25) show low levels of everyday ecological behavior (Girandola & Weiss, 2010), it can be argued that mimicry has led participants to become more honest in their responses to the interviewer.

Of course this argument is speculative given the fact that we do not really know the real level of the participants' ecological behaviors. For example, we do not know if the participants really select their household wastes. However, there are some arguments that have led us to suspect that participants gave more honest responses to the interviewer when they were mimicked. Firstly, research found that participants who were mimicked by a confederate subsequently reported a higher mean of liking for the confederate (Chartrand & Bargh, 1999; LaFrance, 1979; Maurer & Tindall, 1983) and further research found that in survey, a positive appreciation of the interviewer influenced the responses with respondents wanting to please the interviewer by over-reporting good behavior or under-reporting bad behavior (Tourangeau & Yan, 2007). In France, ecological behaviors are perceived favorably and people who displayed such behavior are perceived positively (Girandola & Weiss, 2010). Research on mimicry has found that people who were mimicked reported greater desire to create rapport and affiliation with the mimicker (Lakin & Chartrand, 2003). Thus, if participants wanted to please the mimicker interviewer and to create positive rapport with her, we do not understand why they admitted less ecological behaviors. Given this social desirability bias we expected to find that the participants would admit higher ecological behaviors. Contrary to this expectation, we found the reverse effect which led us to suspect that participants have displayed more honesty in their responses when they were mimicked.

For Lakin et al., (2003), automatic mimicry has a 'social glue' function, binding people together and creating harmonious relationships. If we mimic others in order to create affiliation, we may be able to perceive that others who mimic us are expressing a desire to create affiliation. It has been found that honesty towards unknown interlocutors is a way of establishing positive initial interaction (Knapp, 2008). It has also been found that people who are mimicked reported greater confidence, professional qualities such as honesty, toward the mimicker (Jacob, Guéguen, Martin & Boulbry, 2011). Maddux et al., (2008) also suggested that imitation induced confidence, that, in turn, facilitated the transmission of sensitive or accurate information between competitors. Congruent with the result of this study, we could state that confidence induced by imitation could have facilitated more honest answers toward the mimicker.

Thus, on the basis of our study, we can argue that when participants nonconsciously perceive the desire of the mimicker to interact with them in a friendly way, they will probably want to reciprocate this positive behavior by becoming more honest towards the mimicker. Our results could also be explained in terms of selfmanagement. Kouzakova, Karremans, Van Baaren and Van Knippenberg (2010), have observed that imitation increased self-esteem of the individual mimicked. Thus, it could be argued that once mimicked, the participants would feel less needs of increasing their self-value toward the mimicker that, in turn, led them to give more honest responses to the mimicker. At least, our results could also be explained in term of similarity effect created by mimicry. Guéguen and Martin (2009) found that similarity and mimicry were clearly related. Thus, in our study, the mimicker could had been perceived him/her-self to be similar than the participant which, in turn, led him/her to gave more honest responses.

Further studies are now necessary to evaluate if people become more honest in their responses after being mimicked by someone or if they become more honest only with the mimicker. It would be interesting to test this hypothesis by using two interviewers with a first interviewer mimicking the participant in a first part of a survey and a second interviewer who will not use mimicry in a second part of the survey. It would also be interesting to test the generalisation of the mimicry effect on surveys of various topics. The question still remains whether participants become more honest only for surveys on ecological behaviors or whether they become completely honest.

5. REFERENCES

Bailenson, J. N. & Yee, N. (2005). Digital chameleons: Automatic assimilation of nonverbal gestures in immersive virtual environments. Psychological Science, 16(10), 814-819. [ Links ]

Chartrand, T. L. & Bargh, J. A. (1999). The chameleon effect: The perception-behavior link and social interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(6), 893-910. [ Links ]

Guéguen, N. (2009). Mimicry and Women Attractiveness: An Evaluation in a Courtship Context. Social Influence, 4(4), 249-255. [ Links ]

Guéguen, N. & Martin, A. (2009). Incidental similarity facilitates behavioural mimicry. Social Psychology, 40(2), 88-92. [ Links ]

Guéguen, N., Martin, A. & Meineri, S. (2011). Mimicry and Altruism: An evaluation of mimicry on explicit helping request. The Journal of Social Psychology, 151(1), 1-4. [ Links ]

Jacob, C., Guéguen, N., Martin, A. & Boulbry, G. (2011). Retail Salespeople's Mimicry of Customers: Effects on Consumer Behavior. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 18(5), 381-388. [ Links ]

Kouzakova, M., Karremans, J. C., Van Baaren, R. B. & Van Knippenberg, A. (2010). A stranger's cold shoulder makes the heart grow fonder: Why not being mimicked by a stranger enhances longstanding relationship evaluations. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 1(1), 87-93. [ Links ]

Lakin, J. L. & Chartrand, T. L. (2003). Using nonconscious behavioral mimicry to create affiliation and rapport. Psychological Science, 14(4), 334-339. [ Links ]

Lakin, J. L., Jefferis, V. E., Cheng, C. M. & Chartrand, T. (2003). The chameleon effect as social glue: Evidence for the evolutionary significance of nonconscious mimicry. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 27(3), 145-162. [ Links ]

Girandola, F. & Weiss, K. (2010). Psychologie et développement durable. Paris: Editions In Press. [ Links ]

Knapp, M. L. (2008). Lying and deception in human interaction. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. [ Links ]

LaFrance, M. (1979). Nonverbal synchrony and rapport: Analysis by the cross-lag panel technique. Social Psychology Quaterly, 42(1), 66-70. [ Links ]

Maddux, W. W., Mullen, E. E. & Galinsky, A. D. (2008). Chameleons bake bigger pies and take bigger pieces: Strategic behavioral mimicry facilitates negotiation outcomes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44(2), 461-468. [ Links ]

Maurer, R. E. & Tindall, J. H. (1983). Effects of postural congruence on client's perception of counselor empathy. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 30(2), 158-163. [ Links ]

Tourangeau, R. & Yan, T. (2007). Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychological Bulletin, 133(5), 859-883. [ Links ]

Van Baaren, R. B., Holland, R. W., Kawakami, K. & Van Knippenberg, A. (2004). Mimicry and prosocial behaviour. Psychological Science, 15(1), 71-74. [ Links ]

Van Baaren, R. B., Holland, R. W., Steenaert, B. & Van Knippenberg, A. (2003) Mimicry for money: Behavioral consequences of imitation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 39(4), 393-398. [ Links ]