Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

International Journal of Psychological Research

Print version ISSN 2011-2084

int.j.psychol.res. vol.7 no.1 Medellín Jan./June 2014

Support to Military or Humanitarian Counterterrorism Interventions: The Effect of Interpersonal and Intergroup Attitudes

Apoyo a Intervenciones Contraterroristas Humanitarias o Militares: El efecto de las Actitudes Interpersonales e Intergrupales

Stefano Passinia,*, and Piergiorgio Battistellib

a Dipartimento di Scienze dell'Educazione, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy.

b Dipartimento di Psicologia, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy.

* Corresponding author: Stefano Passini, Dipartimento di Scienze dell'Educazione, University of Bologna. Address: Via Filippo Re, 6 -40126 - Bologna, Italy. Phone: +39.051.2091618 ; Mobil: +39.339.2051662 ; Fax: +39.051.2091489. Email address: s.passini@unibo.it

ARTICLE INFO

Article history: Received: 21-12-2013 Revised: 01-03-2014 Accepted: 15-03-2014

ABSTRACT

Recently, new interest in terrorism and psychological factors related to supporting the war on terrorism has been growing in the field of psychology. The aim of this study was to examine the effect of various socio-political attitudes on the level of agreement with military and humanitarian counterterrorism interventions. 270 Italian participants responded to a news article concerning measures against terrorism. Half of the participants read an article regarding a military intervention while the other half read about a humanitarian intervention. They then evaluated the other type of intervention. Results showed that military intervention was supported by people with high authoritarian, dominant, ethnocentric attitudes and by people who attach importance to both positive and negative reciprocity norms. Instead, none of these variables was correlated with humanitarian intervention. Finally, there was a considerable influence of media on the acceptance of both interventions.

Key words: Terrorism, support to war, authoritarianism, ethnocentrism, media.

RESUMEN

Recientemente, ha estado creciendo en el campo de la psicología un nuevo interés en el terrorismo y los factores psicológicos relacionados al apoyo de la lucha contra el terrorismo. El objetivo de este estudio fue el de examinar el efecto de varias actitudes socio-políticas en el nivel de aceptación de las intervenciones contraterroristas humanitarias y militares. 270 participantes italianos respondieron a un artículo sobre medidas contras el terrorismo. La mitad de los participantes leyeron un artículo acerca de intervenciones militares mientras que el resto leyó sobre la intervención humanitaria. Luego, todos evaluaron el otro tipo de intervención. Los resultados mostraron que la intervención militar fue apoyada por personas con actitudes autoritarias, dominantes, y etnocéntricas y por personas que adscriben importancia a las normas de reciprocidad tanto negativas como positivas. En cambio, ninguna de estas variables fueron correlacionadas con la intervención humanitaria. Finalmente, había una influencia considerable de los medios de comunicación en la aceptación de ambas intervenciones.

Palabras clave: Terrorismo, apoyo a la guerra, autoritarismo, etnocentrismo, medios de comunicación.

1. INTRODUCTION

New interest in terrorism has been growing in the field of psychology after the terrorist attacks on the United States of America on September 11, 2001 (popularly known as '9/11'). Studies have mainly focused on the definition of terrorism (Kruglanski & Fishman, 2006; Passini, Palareti, & Battistelli, 2009), on the effect of terrorist news in generating a cultural climate of fear (Jarymowicz & Bar-Tal, 2006; Mythen & Walklate, 2006), and on the effect of terrorist news on prejudice against groups of people, especially the Arabs (Das, Bushman, Bezemer, Kerkhof, & Vermeulen, 2009; Skitka, Bauman, & Mullen, 2004). Instead, a smaller number of studies have analyzed the psychological factors related to supporting the war on terrorism. We argue that this is a relevant topic for understanding people's intergroup attitudes and the influence of terrorist events and news on hostile intergroup relations.

1.1. Terrorism and the War on Terrorism

Since the 9/11 attacks, the issue of terrorism has extremely influenced political and economic decisions across the world (Chomsky, 2002). Indeed, terrorism was not only an US affair. Since it has been conceived - in both terrorist and anti-terrorist proclamations - as a cultural and transnational clash, the 9/11 attacks have also influenced European political and military decisions. For instance, "Operation Enduring Freedom" (i.e. the counterterrorism war in Afghanistan after 2001) actively involved the United States, the United Kingdom, Italy, France, Germany, Canada, Australia and Poland.

As for other international wars, the war on terrorism has divided the public opinion between supporters and opponents of military interventions. For instance, although Italy was engaged in war in Afghanistan and sent troops to the region, there was also great opposition against the war and many peace manifestations were organized. Moreover, the debate on the legitimacy of the Italian intervention has been highly charged both in the Italian Parliament and the media. From a psychosocial perspective, it is interesting to understand which variables influence the support for, or the opposition against, this type of war.

Some studies (Agnew, Hoffman, Lehmiller, & Duncan, 2007; Federico, Golec, & Dial, 2005) have underlined the role of psychological reaction to terrorism in understanding public support for government antiterrorist policies. These studies have shown that terrorist events - when defined as being serious threats to national security - usually promote support for military actions. Furthermore, many scholars (Bonanno & Jost, 2006; Crowson, DeBacker, & Thoma, 2005; Heaven, Organ, Supavadeeprasit, & Leeson, 2006; McFarland, 2005) have pointed out the effect of both Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA) and Social Dominance Orientation (SDO) in predicting attitudes related to the use of military aggression as part of the war on terror. RWA is defined as the covariation of three attitudinal clusters: submission to authority, aggression against conventional targets, and conventionalism (Altemeyer, 1996). SDO identifies "a general attitudinal orientation toward intergroup relations, reflecting whether one generally prefers such relations to be equal versus hierarchical" (Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, & Malle, 1994, p. 742). Crowson and colleagues (2005) and McFarland (2005) demonstrated that both RWA and SDO are related to support for the U.S.-led attack upon Iraq in March 2003. Similarly, Bonanno and Jost (2006) demonstrated that RWA was positively associated with support for the war in Afghanistan.

Moreover, as some studies (see Huddy, Feldman, Taber, & Lahav, 2005; Lavine, Lodge, & Freitas, 2005) have pointed out, a high-threat perception, such as a terrorism threat, increases the effect of authoritarianism on the expression of other political attitudes (e.g. conservatism) and enhances ingroup favouritism, which is to favour ingroup members and discriminate against outgroup members (see Brown, 2000). The issue of the outgroup threat is fundamental in studying terrorism and counterterrorism support. Following the 2001 terrorist attacks, the media have generally enhanced a climate of fear (Mythen & Walklate, 2006) to the point that many people feel the existence of a sense of threat to both their individual and group security. This perception of threat influences the salience of social categorization separating the allies ("us") from the terrorists ("them") (Oswald, 2005).

1.2. We vs. Them: Terrorism in an Intergroup Perspective

Given the relevance of the perception of threat in the face of terrorism and in enhancing ingroup vs. outgroup antinomy, the support for the war on terrorism could also be analyzed in an intergroup perspective. Therefore, in the present study, in addition to examining authoritarianism and social dominance orientation, we also focused on two variables specifically related to ingroup vs. outgroup antinomy: ethnocentrism and self-categorization.

According to Tajfel's Social Identity Theory (SIT) (Tajfel, 1978; Tajfel & Turner, 1986), ingroups strive not only for differentiation from outgroups but for positive distinctiveness, seeking ingroup-outgroup comparisons that favour the ingroup over other groups. Various studies on intergroup relations have focused on the tendency for ingroup favouritism. These studies have shown that ingroup favouritism may be linked to negative attitudes toward the other groups, such as ethnocentrism, referring to perceiving the outgroup as inferior and less valuable (LeVine & Campbell, 1972). These findings are consistent with research into the effects of threat in intergroup relations, which has found that threat is associated with prejudice and negative attitudes toward outgroups (Stephan & Renfro, 2002). As also suggested by Kam and Kinder (2007), ethnocentrism should therefore be linked to the importance attached to the use of military force in a terrorist-threat scenario.

In line with the social identity theory, self-categorization theory asserts that self-conception occurs on multiple levels of inclusiveness (Turner, 1985). Self-categorization refers to the assumption that behaviors, cognitions and feelings will be determined by different levels of cognitive categorization of the Self (Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987). That is, by changing their self-definition in terms of group membership people also categorize the other groups as ingroup or outgroup (Haslam, Oakes, Reynolds, & Turner, 1999). In particular, the literature (see Gaertner et al., 2000) has shown that the use of a more inclusive self-categorisation - by which individuals refer to a more inclusive group in defining themselves - reduces intergroup bias and conflict (Klandermans, Sabucedo, & Rodriguez, 2004). Instead, a self-categorization restricted to one's own country may enhance the relationship between perceived threat and prejudice towards outgroups (Duckitt & Mphuthing, 1998). These studies suggest that the more inclusive is the self-categorization, the less people should support military counterterrorism interventions.

1.3. Me vs. the Others: The Reciprocity Norm

Another concept related to the perception of threat, and therefore possibly to terrorism and counterterrorism measures, is the reciprocity norm. As Eisenberger, Lynch, Aselage and Rohdieck (2004, p. 1) asserted, "harm returned for harm received is a venerable moral precept that provides social approbation for revenge and that serves the societal objective of discouraging mistreatment." In the authors' opinion, interpersonal relationships are guided by norms of reciprocity that prescribe being good to those who are good to us (positive reciprocity) and bad to those who are bad to us (negative reciprocity). This way of dealing with social interactions, based on the concept of deservingness, may also influence the support for military intervention in other countries.

Gouldner (1960) described the negative reciprocity norm as "a unitary set of beliefs favoring retaliation as the correct and proper way of responding to unfavorable treatment" (Eder, Aquino, Turner, & Reed, 2006, p. 810). This is a conception of justice based on an "eye for an eye" principle (Eisenberger et al., 2004). Akin to authoritarian and social dominance attitudes, the negative reciprocity norm endorsement gives people justification for using aggression against undesirable groups (Eder et. al, 2006). As demonstrated by some studies (Eisenberger et al., 2004; Perugini, Gallucci, Presaghi, & Ercolani, 2003), endorsing the negative reciprocity norm has indeed behavioral consequences: i.e. individuals with high negative reciprocity norm endorsement were more likely than their low negative reciprocity norm counterparts to punish those who had previously treated them in a negative manner. Moreover, Eder et al. (2006) have demonstrated that people's endorsement of negative reciprocity might also affect perceptions of, and reactions to, political events.

On the other side, the positive reciprocity norm refers to a general norm encouraging the return of favourable treatment (Eisenberger et al., 2004). In some ways, the positive reciprocity norm may be seen as a positive intergroup attitude (i.e., allophilia) and thus as potential antecedents of social policy support for multiracial individuals (Pittinsky & Montoya, 2009). However, we believe that the positive reciprocity norm should not necessarily support tolerance and decrease prejudice, as it conceivably is a psychological mechanism more related to a sense of indebtedness and dutifulness towards those who had previously treated someone positively. Thus, this attitude might be better considered narrowly as "I treat him/her well if and only if he/she treats me well."

1.4. The Role of Media

Finally, a variable related to the perception of terrorism threat is the trust in media information. As Altheide (2006) pointed out, since 9/11 the mass media have contributed towards fostering a climate of fear and uncertainty. Every day the mass media talk about a "terrorist world" and about "a war against the empire of evil." Several authors (Chadee & Ditton, 2005; Furedi, 2002; Mythen & Walklate, 2006) have people's perception of "bad event" risks. For instance, Mythen and Walklate (2006) analyzed the ways in which the United Kingdom government communicated the terrorist threat after the terror attacks in New York, Madrid and London. The authors highlighted that terrorist threat was used to gaining public support for international military intervention and the tightening-up of national law and order measures.

In this sense, the persistence of news related to terrorism risk might amplify or lessen people's fears and feeling of being threatened, as well as people' support for war on terrorism (Mythen & Walklate, 2006). Indeed, media enhance a sense of threat and amplify the ingroup vs. outgroup antinomy by identifying a clear enemy.

1.5. The Present Research

The aim of this study was to broaden our current knowledge concerning support predictors for international interventions in a terrorist-threat condition by integrating the study of the effect of authoritarian and social dominance attitudes with that of variables related to interpersonal relations (i.e. the negative and the positive reciprocity norm) and related to intergroup relations (i.e. ethnocentrism and inclusive self-categorisation). In addition, the role of the media and their influence on supporting anti-terrorism interventions was investigated.

Moreover, we analyzed not only support for military interventions but also support for humanitarian ones, i.e. the allocation of public funds to help the civilian population. This variable was added because we think that in order to have a more complete understanding of the support for international interventions, one has to consider not only the military but also other interventions that may be considered appropriate (such as a humanitarian intervention). Indeed, in an age where military interventions against other nations are approved by a large majority of people - e.g. the recent Libyan war in 2011 - our interest was to better understand whether the same attitude variables predicted support for military and humanitarian intervention. Moreover, in research on support for military intervention it has been argued (e.g. Cohrs, Maes, Moschner, & Kielmann, 2003) that denial of alternatives is an important factor driving support for military intervention (in line with Margaret Thatcher's "TINA" principle - There Is No Alternative).

We hypothesized that the approval of military intervention is positively related to authoritarianism, social dominant, ethnocentrism, negative and positive reciprocity attitudes and to an elevated trust in media information. Moreover, military intervention was expected to be negatively related to a more inclusive self-categorisation. With regards to humanitarian intervention, we hypothesized that its approval is positively related to inclusive self-categorisation, while negatively related to authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, ethnocentrism and the negative and positive reciprocity norms. We did not expect humanitarian intervention to be associated with trust in the media.

2. METHOD

2.1. Participants

A total of 270 Italian participants (46.6 % women) served as the participants. They were recruited from amongst the general population in different settings (e.g. public libraries) in Bologna, a large city located in Northern Italy. Participants' ages ranged from 18 to 54 years (M = 24.90, SD = 6.98). With regards to level of education, 72.5 % reported they had obtained a high school diploma and 27.5 % a university degree. No participants were excluded from the analyses.

2.2. Procedure

The design comprised two conditions: humanitarian vs. military intervention. Participants were asked to read a short news article which had presumably appeared in a newspaper. Adapted from a description of the growth of the Taliban movement in Afghanistan, the article was about the growth of a radical Islamic terrorist movement in an imaginary country (given the name Arjabadan). The article declares that this movement is supposedly connected to other terrorist movements (such as Al-Qaeda) and that Amnesty International has raised concerns over human rights violations in Arjabadan. Then, the article states that the United Nations (UN) has requested 200 billion dollars to develop an intervention to restore democracy in Arjabadan. Using a random assignment, some participants (n = 140) were asked to evaluate a military intervention to restore democracy in Arjabadan (military condition), while others (n = 130) evaluated a humanitarian intervention to help the civilian population of Arjabadan (humanitarian condition). Gender was balanced in each of the two conditions [X2 (1, N = 268) = .60, p = ns]. The dependent variables (all on a seven-point scale) were the acceptance of the intervention (acceptance), the effectiveness of the intervention (effectiveness), the convenience in relation to Italy's economic conditions (cost), the ethics of the intervention (ethics) and the legitimacy of the intervention (legitimacy). Finally, participants were asked to what extent they would accept the alternative intervention (alternative acceptance): "to what extent would you agree if the same amount of money was allocated to a humanitarian [military] intervention instead?"

2.3. Measures

After reading and responding to the short news article, the participants were asked to fill out the following measures.

Authoritarian submission. This construct was measured by a 4-item scale based on Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA) (Altemeyer, 1996) and constructed and validated by Passini (2008). An example of item is "our country will be great if we do what the authorities tell us to do. People responded to each item on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The scale had acceptable reliability (α = .66).

Social Dominance Orientation (SDO). Social dominance orientation was measured with the 10-item Italian version of the SDO6 scale (Pratto et al., 1994). All the items were measured on a 7-point scale, anchored at strongly agree and strongly disagree. A sample item is "Some groups of people are simply inferior to other groups." The scale had acceptable reliability (α = .75).

Ethnocentrism. To assess the level of ethnocentrism, we asked the participants to respond to 12 items from the Ethnocentrism Scale (Aiello & Areni, 1998). All the items were measured on a 7-point scale, anchored at "strongly agree" and "strongly disagree." A sample item is "multi-ethnic societies will lead to the destruction of our culture." The scale had high reliability (α = .89).

Negative Reciprocity Norm (NRN). The negative reciprocity norm is the personal moral code specifying retaliation as a proper response to wrongdoing (Eder et al., 2006). Belief in NRN was assessed using the 14-item negative reciprocity norm scale developed by Eisenberger et al. (2004). Participants responded to the statements by expressing their agreement on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). A sample item is "If someone treats you badly, you should treat that person badly in return." NRN scale had high reliability (α = .93).

Positive Reciprocity Norm (PRN). The positive reciprocity norm refers to a general norm encouraging the return of favourable treatment (Eisenberger et al., 2004). Belief in PRN was assessed using the 10-item positive reciprocity norm scale developed by Eisenberger et al. (2004). Participants responded to the statements by expressing their agreement on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).

A sample item is "If someone does me a favour, I feel obligated to repay them in some way." PRN scale had acceptable reliability (α = .79).

Inclusive Self-Categorization Index (ISC). Participants indicated their agreement on a 4-point scale to these items (α = .64): (1) I consider myself a world citizen; (2) I consider myself an Italian citizen; (3) I consider myself a EU citizen. ISC index was constructed as the sum of item 1 and 3 less item 2. The index varied from -2 to +7 and was recategorized on a 10-point scale with min = 1 and max = 10.

Trust in media. Participants indicated their trust in TV news and newspaper information on a 7-point scale (from 1 = not at all to 7 = very much).

3. RESULTS

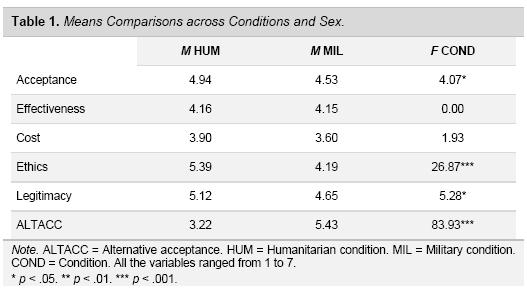

Participants accepted the humanitarian intervention more, they perceived it to be more ethical and legitimate than the military intervention (see Table 1). No effect was found for effectiveness and cost. A large condition effect was found for the acceptance of the alternative intervention. By comparing the means of the acceptance of each intervention as a primer vs. an alternative intervention, we found a large significant effect for the military intervention [M military as a primer = 4.53 vs. M military as an alternative = 3.22, F(1, 269) = 29.46, p < .001] and a significant effect for the humanitarian intervention [M humanitarian as a primer = 4.94 vs. M humanitarian as an alternative = 5.43, F(1, 269) = 5.70, p < .05]. That is, military intervention was accepted more when it was evaluated as a primer than as an alternative, while the same effect was weaker for humanitarian intervention.

As illustrated in Table 2, participants reported moderate levels of ethnocentric and authoritarian attitudes, low levels of dominance attitudes, and were less favourable to the negative reciprocity norm and more favourable to the positive reciprocity norm. Moreover, they had relatively high scored on the ISC scale and considered media information as moderately trustworthy.

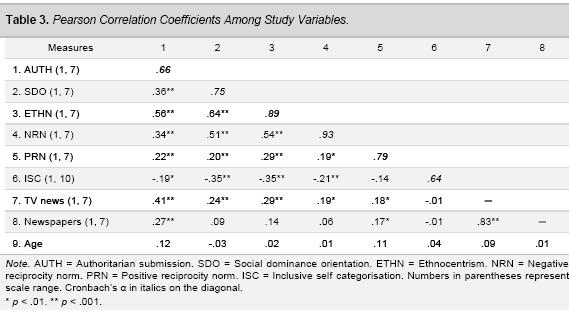

Bivariate correlations showed different patterns of correlations for the two conditions (see Table 2) (Pearson correlation coefficients among all the study variables are presented in Table 3). Firstly acceptance was not correlated with alternative acceptance in the humanitarian condition, while they were negatively correlated in the military condition. Secondly, acceptance towards the humanitarian intervention was positively correlated only with trust in media (contrary to our hypothesis). Instead, as hypothesized, the acceptance towards the military condition was positively correlated with authoritarian submission, social dominance orientation, ethnocentrism, the negative and the positive reciprocity norm, and trust in media. Similarly, the acceptance of military intervention as an alternative was positively correlated with all the same variables apart from the positive reciprocity norm and it was negatively correlated with inclusive self-categorisation.

Then, as hypothesized, the acceptance of the humanitarian intervention as an alternative was negatively correlated with authoritarian submission, social dominance orientation, ethnocentrism, the negative reciprocity norm and positively correlated with inclusive self-categorisation.

4. DISCUSSION

The main objective of this study was to understand the effect of various socio-political attitudes on the approval of either a humanitarian or a military intervention on a nation linked to terrorist groups. Since the literature has mainly focused on support to military operations, we indeed considered to compare these two interventions and to analyse the effect of various interpersonal and intergroup attitudes on their support.

First, as it could be expected (since it is more socially accepted), results show that participants accept the humanitarian more than the military intervention. However, values concerning the military intervention are above the midpoint of the response scale and are not so different from those regarding the humanitarian strategy. This is confirmed by data on the effectiveness and cost of the intervention; the scores do not substantially differ between the two interventions. In particular, participants consider humanitarian and military interventions as equally effective methods for restoring democracy. Moreover, interventions are considered both quite legitimate and ethical, even if the humanitarian is preferred over the military intervention (but, again, both scores are above the midpoint of the response scale). As concerns the convenience in relation to the economic conditions of Italy, all interventions are not considered to be so convenient. Thus, in general, the data show that the participants are quite in agreement with interventions to restore democracy both when these are supposed to help the population and when these imply the use of military strength.

A different result emerged when comparing alternative acceptance of military and humanitarian interventions. In this case, there is a considerable difference in its acceptance: i.e., military intervention as an alternative to the humanitarian one is not accepted, whereas humanitarian intervention as an alternative to the military one is largely accepted. As the comparison of primers vs. alternative interventions suggests, when people evaluate the military intervention as a primer they accept it more than when they evaluate it as an alternative to the humanitarian intervention. That is, people do not have many reservations in directly declaring they back military action, except when they compare it to and evaluate it after humanitarian measures. Perhaps when they evaluate the military action as a primer they do not have other alternative interventions in mind. Or perhaps recent events (It should be noted that data were collected in 2007) connected to terrorism and the rather broad-ranging media consensus in describing the so-called "war on terror" as a desirable action -where it is not the "only possible" action - may have influenced the social desirability of supporting military actions (which are often misleadingly labelled as "peacekeeping operations"). That is, it is no longer social desirable not to support the war. In this sense, these data suggest the relevance of media and politics in describing military interventions as "the only possible choice."

Second, as hypothesized, all the attitude variables considered in the research are correlated with the acceptance of military intervention (both as a primer and as an alternative to the humanitarian one). In accordance with the literature, military intervention is supported by people with high authoritarian and dominant attitudes. Moreover, in addition to these well-known effects, the present research shows that military operations are also supported by people who attach importance to ethnocentric attitudes and to both positive and negative reciprocity norms. These results confirm that support to the use of military force as a counterterrorism intervention is influenced by various interpersonal and intergroup attitudes. These variables are focused on the perception of a distance towards other people and social groups by which the others are seen as a threat rather than as an opportunity for one's own society.

None of these variables is instead correlated with humanitarian intervention. However, it is interesting to note that these variables did not impact participants' responses to the humanitarian story, although they did when evaluating the humanitarian intervention as an alternative to the military one. Perhaps, in the former case, there is an influence of social desirability. That is, authoritarian, dominant, and ethnocentric people do not explicitly oppose humanitarian actions, even in those cases where they would not be willing to support and fund them. However, perhaps the evaluation of the humanitarian intervention, as opposed to the military intervention, makes those individuals come forward. Moreover, there is an influence of inclusive self-categorization, by which the more people categorize themselves inclusively way, the more they support the humanitarian intervention and the less they accept the military one. These effects emerge just when participants evaluated the alternative intervention. Perhaps, the awareness of the two options of intervention makes stronger the effect of one's own way to categorize in relation to the world. Thus, when people categorize themselves in a more extended way, they tend to remove the boundaries and the differences between themselves and others and to refer to a global dimension that includes every human being. Indeed, as some scholars (see Gaertner, Dovidio, Anastasio, Bachman, & Rust, 1993) pointed out, the categorization of other ethnic group members as member of a wider community helps people to reduce bias and hostility. Instead, an exclusive categorization leads people to attach more relevance to discriminatory attitudes (see Passini, 2010, 2013) and therefore to prefer the use of the force to solve threatening situations.

It should be noted that people with high scores on the positive reciprocity norm tend to accept the military intervention more than people with low results on this variable. Thus, as we suggested in the introduction, the positive reciprocity norm does not decrease prejudice, but it might instead turn out to be a support for intolerance. Taken as a whole, the results of both negative and positive reciprocity norms highlight a view of relationships where "I only do good to those who did good to me, and I do bad to those who did bad to me." In other words, I am a friend of whoever is my friend, and I am an enemy of my own enemies. Thus, as a confirmation of the social identity theory and intergroup studies (Tajfel, 1978; Tajfel & Turner, 1986), the reciprocity principle is the "ethic" norm that builds a worldview based on the us/them opposition, and may thus be defined as a sort of interpersonal ethnocentrism. That is, both reciprocity norms imply a reference to an "eye for an eye" form of justice that does not foster the encounter with the other but rather supports a friend/foe antinomy.

Finally, there was a considerable influence of media on the acceptance of both interventions. In support of the literature on the culture of fear and on the media influence on public opinion (see Mythen & Walklate, 2006), trust in TV news and in newspaper information had a strong effect on the acceptance of the interventions. This data may be explained by considering that media and news reports continuously warn about the need to export democracy around the world by means of military or humanitarian international operations. In this sense, people who have more trust in media may be lead to consider these interventions as something to be unquestionably supported.

5. LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

This research has some limitations which should be kept in mind for future research. First, the difference in evaluating the intervention as the primer and as an alternative should be analyzed in greater depth. The results are indeed quite clear but they should be confirmed by the use of other methodologies and the participants should be given option of other alternatives apart from military and humanitarian interventions. For instance, we did not consider non-intervention as another alternative intervention modality. In light of different recent evaluations of public opinion concerning the coalition intervention in Libya in 2011, we think that it should be interesting to understand which attitude variables support a decision for non-intervention and if this is contextual (i.e. linked to the specific intervention) or linked to some personality traits and/or some general psycho-political attitudes of the individual. Moreover, humanitarian interventions are often blended with military involvement, making the difference between the two less clear in people's minds. This issue warrants further investigation. Second, the level of education should be analyzed more in depth as well as the possible effect of other demographic variables. Even if our data did not show any influence of the level of education, this variable may be correlated to the use of media and to the access to information, influencing in turn the acceptance of the interventions. Third, the results should be confirmed in a larger sample and at different times. Indeed, it may be interesting to analyze how the acceptance of different interventions (i.e. military, humanitarian, economic, etc.) might change in response to different events. For instance, by evaluating whether people answer differently when responding to a scenario of a radical Islamic counterterrorism intervention or an intervention against a less mass media-fueled and menacingly-perceived terrorist group. Recent studies (e.g. Duckitt & Fisher, 2003; Feldman & Stenner, 1997; Perrin, 2005) have indeed shown that when the threat of events is modulated, people respond differently to them: i.e. in the presence of threat, they scored higher on prejudicial attitudes. Finally, the issue of media influence should be analyzed in greater depth. In particular, a possible difference between TV news and newspaper news should be specifically deepened by, for instance, giving the participants different articles to read (e.g. about poverty or terrorism) or by having them view videos (e.g. with images of poor people or terrorists).

6. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the results of this research confirm the relevance of authoritarianism and social dominance orientation in explaining support for the war on terrorism. Additionally, the findings cast light on the importance of some variables on the everyday sense of justice - e.g. the norms that regulate interpersonal reciprocity. Indeed, as an implication for future research, the study of people's reactions to terrorism and to counterterrorism measures should consider not only intergroup variables (e.g. attitudes towards the other groups and prejudices), but also how people consider their everyday relationships with other people and how they react to the favours/harms resulting directly from other people (i.e. norms of reciprocity). In this context, the sense of threat can be perceived at an intergroup level but also at a personal level and these two levels are closely intertwined. As suggested in the literature (see Eder et. al, 2006), the importance given by people to both negative and positive reciprocity norms can inform us about what people think of the intergroup relationships. Furthermore, another important implication of our study is related to the result demonstrating the influence mass media can have on terrorism issues. This influence is quite evident in the effect of providing certain information, instead of other information or partial information, about events and intervention options in response to a terror event. We suggest that the media effect needs to be strongly considered when examining the attitudes towards terrorism interventions.

7. REFERENCES

Agnew, C., Hoffman, A., Lehmiller, J., & Duncan, N. (2007). From the interpersonal to the international: understanding commitment to the "war on terror." Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 1559-1571. [ Links ]

Aiello, A., & Areni, A. (1998). Un aggiornamento della scala di De Grada ed altri (1975) per la misura dell'etnocentrismo [An updating of De Grada et al. scale (1975) for the measurement of Ethnocentrism]. Rassegna di Psicologia, 15(2), 145-160. [ Links ]

Altemeyer, B. (1996). The authoritarian specter. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Altheide, D. L. (2006). Terrorism and the politics of fear. Cultural Studies → Critical Metodologies,6, 415-439. [ Links ]

Bonanno, G. A., & Jost, J. T. (2006). Conservative shift among high exposure survivors of the September 11th terrorist attacks. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 28, 311-323. [ Links ]

Brown, R. (2000). Social identity theory: Past achievements, current problems and future challenges. European Journal of Social Psychology, 30, 745-778. [ Links ]

Chadee, D. & Ditton, J. (2005). Fear of crime and the media: Assessing the lack of relationship. Crime Media Culture, 1, 322-332. [ Links ]

Chomsky, N. (2002). 9-11. New York: Metropolitan Books. [ Links ]

Cohrs, J. C., Maes, J., Moschner, B., & Kielmann, S. (2003). Patterns of justification of the United States' War against terrorism in Afghanistan. Psicología Política, 27, 105-117. [ Links ]

Crowson, H. M., DeBacker, T. K., & Thoma, S. J. (2005). Does authoritarianism predict post-9/11 attitudes? Personality and Individual Differences, 39, 1273-1283. [ Links ]

Das, E., Bushman, B. J., Bezemer, M. D., Kerkhof, P., & Vermeulen, I. E. (2009). How terrorism news reports increase prejudice against outgroups: A terror management account. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 453-459. [ Links ]

Duckitt, J., & Fisher, K. (2003). The impact of social threat on worldview and ideological attitudes. Political Psychology, 24, 199-222. [ Links ]

Duckitt, J., & Mphuthing, T. (1998). Group identification and intergroup attitudes: A longitudinal analysis in South Africa. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 80-85. [ Links ]

Eder, P., Aquino, K., Turner, C., & Reed, A. (2006). Punishing Those Responsible for the Prison Abuses at Abu Ghraib: The Influence of the Negative Reciprocity Norm (NRN). Political Psychology, 27, 807-821. [ Links ]

Eisenberger, R., Lynch, P., Aselage, J., & Rohdieck, S. (2004). Who takes the most revenge? Individual differences in negative reciprocity norm endorsement. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 787-799. [ Links ]

Federico, C., Golec, A., & Dial, J. (2005). The relationship between the need for closure and support for military action against Iraq: Moderating effects of national attachment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin,31, 621-632. [ Links ]

Feldman, S., & Stenner, K. (1997). Perceived threat and authoritarianism. Political Psychology, 18, 741 -770. [ Links ]

Furedi, F. (2002). The culture of fear: Risk taking and the morality of law expectations. Cassell: London. [ Links ]

Gaertner, S. L., Dovidio, J., Anastasio, P., Bachman, B., & Rust, M. (1993). The common ingroup identity model: Recategorization and the reduction of intergroup bias. In W. Stroebe & M. Hewstone (Eds.), European review of social psychology (Vol. 4, pp. 1 -26). London: Wiley. [ Links ]

Gaertner, S. L., Dovidio, J. F., Rust, M. C., Nier, J. A., Baker, B. S.,Ward, C. M., ... Loux, S. (2000). The common ingroup identity model for reducing intergroup bias: Progress and challenges. In D. Capozza, & R. Brown (Eds.), Social identity processes (pp. 133-148). London: Sage. [ Links ]

Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25, 161 -178. [ Links ]

Haslam, S. A., Oakes, P. J., Reynolds, K. J., & Turner, J. C. (1999). Social identity salience and the emergence of stereotype consensus. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25, 809-818. [ Links ]

Heaven, P. C. L., Organ, L., Supavadeeprasit, S., & Leeson, P. (2006). War and prejudice: A study of social values, right-wing authoritarianism, and social dominance orientation. Personality and Individual Differences, 40, 599-608. [ Links ]

Huddy, L., Feldman, S., Taber, C., & Lahav, G. (2005). Threat, anxiety, and support of antiterrorism policies. American Journal of Political Science, 49, 593-608. [ Links ]

Jarymowicz, M., & Bar-Tal, D. (2006). The dominance of fear over hope in the life of individuals and collectives. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36, 367-392. [ Links ]

Kam, C. D., & Kinder, D. R. (2007). Terror and ethnocentrism: Foundations of American support for the war on terrorism. The Journal of Politics, 69, 320-338. [ Links ]

Klandermans, B., Sabucedo, J. M., & Rodriguez, M. (2004). Inclusiveness of identification among farmers in The Netherlands and Galicia (Spain). European Journal of Social Psychology, 34, 279-295. [ Links ]

Kruglanski. A. W., & Fishman, S. (2006). Terrorism between "syndrome" and "tool." Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15, 45-48. [ Links ]

Lavine, H., Lodge, M., & Freitas, K. (2005). Threat, authoritarianism, and selective exposure to information. Political Psychology, 26, 219-244. [ Links ]

Levine, R. A., & Campbell, D. T. (1972). Ethnocentrism: Theories of conflict, ethnic attitudes, and group behavior. New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

McFarland, S. (2005). On the eve of war: Authoritarianism, social dominance, and American students' attitudes toward attacking Iraq. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 360-367. [ Links ]

Mythen, G., & Walklate, S. (2006). Communicating the terrorist risk: Harnessing a culture of fear? Crime Media Culture, 2, 123-142. [ Links ]

Oswald, D. L. (2005). Understanding anti-arab reactions post-9/11: The role of threats, social categories, and personal ideologies. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 35, 1775-1799. [ Links ]

Passini, S. (2008). Exploring the multidimensional facets of authoritarianism: Authoritarian aggression and social dominance orientation. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 67, 51-60. [ Links ]

Passini, S. (2010). Moral reasoning in a multicultural society: Moral inclusion and moral exclusion. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 40, 435-451. [ Links ]

Passini, S. (2013). What do I think of others in relation to myself? Moral identity and moral inclusion in explaining prejudice. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 23, 261-269. [ Links ]

Passini, S., Palareti, L., & Battistelli, P. (2009). We vs. them: Terrorism in an intergroup perspective. Revue Internationale De Psychologie Sociale, 22, 35-64. [ Links ]

Perrin, A. J. (2005). National threat and political culture: Authoritarianism, antiauthoritarianism, and the September 11 attacks. Political Psychology, 26, 167-194. [ Links ]

Perugini, M., Gallucci, M., Presaghi, F., & Ercolani, A. P. (2003). The personal norm of reciprocity. European Journal of Personality, 17, 251-283. [ Links ]

Pittinsky, T. L., & Montoya, R. M. (2009). Is valuing equality enough? Equality values, allophilia, and social policy support for multiracial individuals. Journal of Social Issues, 65, 151-163. [ Links ]

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M., & Malle, B. F. (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 741-763. [ Links ]

Schwartz, S. H., & Rubel, T. (2005). Sex differences in value priorities: Cross-cultural and multimethod studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 1010-1028. [ Links ]

Skitka, L. J., Bauman, C. W., & Mullen, E. (2004). Political tolerance and coming to psychological closure following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks: An integrative approach. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 743-756. [ Links ]

Stephan,W. G., & Renfro, C. L. (2002). The role of threat in intergroup relations. In D. M. Mackie, & E. R. Smith (Eds.), From prejudice to intergroup emotions: Differentiated reactions to social groups (pp. 191 -207). Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press. [ Links ]

Tajfel, H. (1978). Social categorization, social identity, and social comparison. In H. Tajfel (Ed.), Differentiation between social groups: Studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 61 -76). London: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity of intergroup behaviour. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7-24). Chicago: Nelson Hall. [ Links ]

Turner, J. C. (1985). Social categorization and the self-concept: A social cognitive theory of group behavoir. In E. J. Lawler (Ed.), Advances in group processes: Theory and research (Vol. 2, pp. 77-122). Greenwich, CT: JAI press. [ Links ]

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., & Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. [ Links ]