Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

International Journal of Psychological Research

Print version ISSN 2011-2084

int.j.psychol.res. vol.7 no.1 Medellín Jan./June 2014

Caregiver's Burden and Quality of Life: Caring for Physical and Mental Illness

Carga y Calidad de Vida de Cuidadores a Cargo de Personas con Dificultades Psicológicas y Mentales

Salvatore Settineria,*, Amelia Rizzob,**, Marco Liottab,*** and Carmela Mentoc,****,*****

a Department of Human and Social Sciences, University of Messina, Messina, Italy.

b School in Psychological Sciences, University of Messina, Messina, Italy

c Department of Neurosciences, University of Messina, Messina, Italy.

* Professor Settineri concept and design of research, definition of intellectual content.

** Dr. Rizzo data acquisition, data analysis, stalistical analysis and manuscript preparation.

*** Dr. Liotta literalure search, clinical studies, experimental studies, data acquisition.

**** Professor Mento design, clinical studies, manuscript preparation, editing, review.

***** Corresponding author: Carmela Mento, Department of Neurosciences, University of Messina, Messina Italy. Consolare Valeria str. 1, 98125 Messina, Italy. Phone numbers: +3390902212978. Email address: cmento@unime.it

ARTICLE INFO

Article history: Received: 12-03-2014 Revised: 05-04-2014 Accepted: 10-04-2014

ABSTRACT

Several studies have been focused on the quality of life of caregivers caring for patients with exclusively physical or mental diseases, but little is known about the differences related to the burden experienced.

This study had as its subject the burden of caregivers and their quality of life involved in helping patients with diseases (1) physical, (2) mental and (3) both pathological conditions. We interviewed 294 caregivers of outpatients undergoing physiotherapic, psychiatric and neuroriabilitative treatment. The evaluation was carried out with three instruments: an informative questionnaire, the Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI) and the Quality of Life Index (QoL -I).

Results show that both the burden and the quality of life are significantly worse for caregivers who care for patients with both physical and mental diseases. Caregivers most disadvantaged are those who indicate as a reason of care the sense of duty rather than the affection. Finally, the sons and daughters, differently from the parents, showed a greater burden of required time and a lower quality of life.

The investigation of the motivational aspects of the caregivers and the increased knowledge of the differences between the emotional experience of parents and children can contribute to the definition of more specific psycho-educational interventions and support.

Key words: Caregivers, Burden, Quality of Life.

RESUMEN

Varios estudios de han enfocado en la calidad de vida de los cuidadores a cargo de pacientes con enfermedades exclusivamente físicas o mentas, pero poco se sabe sobre las diferencias en cuanto a la carga experimentada.

Este estudio tiene como objeto la carga de estos cuidadores y su calidad de vida involucrada en la ayuda que prestan a pacientes con enfermedades (1) físicas (2) mentales y (3) ambos condiciones patológicas. Entrevistamos a 294 cuidadores de pacientes no hospitalizados bajo tratamientos psicoterapéuticos, psiquiátricos o de neurorehabilitación. La evaluación fue llevada a cabo a través de tres instrumentos: un cuestionario informativo, el CBI ( Caregiver Burden Inventory ) y el índice de calidad de vida (the Quality of Life Index/ QuL-I)

Los resultados mostraron que tanto la carga como la calidad de vida eran significativamente peores para los cuidadores que se encargan de pacientes con enfermedades físicas y psicológicas a la vez. Los más desventajados son aquellos que indicaron como razón de su condición de cuidador, el sentido del deber más que por afección al enfermo. Finalmente, los hijos, a diferencia de los padres, mostraron mayor carga de tiempo requerido y una calidad de vida inferior cuando están en el papel de cuidadores.

En conclusión, la investigación de sobre los aspectos motivacionales de los cuidadores y un incremento de conocimiento de las diferencias entre a experiencia emocional de los padres y sus hijos puede contribuir a la definición de apoyo e intervenciones psico-educacionales más específicas.

Palabras clave: Cuidadores, carga emocional o psicológica, calidad de vida.

1. INTRODUCTION

Caregiver is the responsible for the care of someone who has poor mental health, is physically disabled or whose health is impaired by sickness or old age. The role they have taken provides for the following tasks: Take care of someone who has a chronic illness or disease; Managing medications or talking to doctors and nurses on someone's behalf; Help to bathe or dress someone who is frail or disabled; (Grunfeld, et al., 2004) Take care of household chores, meals, or bills for someone who cannot do these things alone (Levine, & Barry, 2003).

There is a strong consensus supporting that caring an individual with disability is burdensome and stressful to many family members and contributes to morbidity. Researchers have also suggested that the combination of loss, prolonged distress, the physical demands of caregiving, and biological vulnerabilities of older caregivers may compromise their physiological functioning and increase their risk for physical health problems, which leads to increased mortality (Schulz, & Beach, 1999).

Physical disease. As for caregivers of people with physical disease, studies has focused on serious pathologies such us cancer (Goldstein, Concato, Fried, Kasl, Johnson-Hurzeler, & Bradley, 2003; Grunfeld, et al., 2004), stroke (Morimoto, Schreiner, & Asano, 2003), traumatic injury (Marsh, Kersel, Havill, & Sleigh, 1998) sclerosis (Chio, A., Gauthier, Calvo, Ghiglione, Mutani, 2005). These studies showed significant levels of anxiety and depression in about one third of caregivers and depressive symptoms in about half of them and revealed a strict connection between burden and low quality of life and an inverse correlation between perceived burden and patients' functional status with burden increasing with the worsening of patients' disability.

Mental illness. Numerous studies have demonstrated that family caregivers of persons with a severe mental illness suffer from significant stresses, experience moderately high levels of burden, and often receive inadequate assistance from mental health professionals. For families who are already confronted with a range of day-to-day problems that affect all aspects of their lives, a member with a severe mental illness may have a significant impact on the entire family system (Saunders, 2003).

Studies agreed with the consideration that, especially in mental illness, caregiver burden is first of all linked with personality and mood of the caregiver himself (da Silva, et al., 2013; Hou, Ke, Su, & Huang, 2008) The stress of dealing with a family member suffering from a mental illness is inversely proportional to a healthy personality and a great resilience (Lautenschlager, Kurz, Loi, Cramer, 2013).

Caregiver burden in mental disorders is strictly linked with severity of the symptoms and the presence of problematic behaviours (Ohaeri, 2003). Most studies has focused on serious mental illness such as mood disorders (da Silva, et al., 2013; Grover, Chakrabarti, Ghormode, Dutt, Kate, & Kulhara, 2013; Zendjidjian, et al., 2012) obsessive compulsive disorder (Grover, & Dutt, 2011; Torres, Hoff, Padovani, & Ramos-Cerqueira, 2012) and schizophrenia (Dyck, Short, & Vitaliano, 1999; Foldemo, Gullberg, Ek, & Bogren, 2005; Grandón, Jenaro, & Lemos, 2008; Hanzawa, et al., 2012; Hou, Ke, Su, & Huang, 2008; Lauber, Eichenberger, Luginbúhl, Keller, & Rõssler, 2003): caring for someone with these pathologies can result in considerable consequences for the caregiver that, usually, are also family members. Results showed how family members are less satisfied with their overall quality of life and are significantly distressed as a result of having a family member with a mental disorder (Foldemo, Gullberg, Ek, & Bogren, 2005; Martens, & Addington, 2001).

Greater burden and lower quality of life were predicted by three fundamental parameters: duration and severity of illness, decreased tangible social support with restriction of caregiver social life and negative feelings of caregiver such as shame, embarrassment, guilt and self-blame (Dyck, Short, & Vitaliano, 1999; Grover, & Dutt, 2011; Lauber, Eichenberger, Luginbúhl, Keller, & Rõssler, 2003).

Pathologies with physical and mental outcomes. Studies on mental and physical illness have focused on neurodegenerative diseases and especially various forms of dementia (Clyburn, Stones, Hadjistavropoulos, & Tuokko, 2000; Papastavrou, Kalokerinou, Papacostas, Tsangari, & Sourtzi, 2007; Razani, et al, 2007; Riedijk, De Vugt, Duivenvoorden, Niermeijer, Van Swieten, Verhey, & Tibben, 2006; Steadman, Tremont, & Davis, 2007).

As regards caregivers who care for patients with neurological disorders, the burden is not so much related to patient memory, self-care, and language skills, but rather to the patient dysphoria and everyday functioning skills. This empirical observation seems to suggest that the caregiver's perceptions of the patient's functioning are the most important determinants of caregiver burden. Objective deficits of the patients in the influence caregiver burden is directly linked by caregiver's perceptions. In addiction, it is severity on the disease that influence the burden of caregiver and also the perception of gravity by the caregiver (Hadjistavropoulos, Taylor, Tuokko, & Beattie, 1994).

Studies showed how these caregivers had a greater burden than those who care for patients with only physical or only mental disorders and how a greater percentage of them (up to 70%) reported depressive symptoms. Important variations in the intensity of perceived burden depended by subjective experiences and social support, but it was also revealed that caregivers of patients exhibiting more disturbing behaviors and functional limitations, received less help from family and friends (Thomas, et al., 2006).

Hypothesis. There are few studies that have provided an empirical comparison between the different pathological conditions that affect the experience of care of caregivers. Glozman (Glozman, 2004) analyzed these aspects focusing on the differences in QoL in various pathological conditions and providing a valuable descriptive analysis. Literature has so far treated separately the consequences in terms of physical and psychological health (quality of life) of caregivers caring for people with chronic physical, mental or neuropsychological disease.

In addition, little is known about the motivational aspects of caregivers and how they can serve as protective factors that can mitigate the development of symptoms due to the assistance. Veltman et al. (Veltman, Cameron, & Stewart, 2002) documented caregivers' perspectives on both the negative and positive aspects of caregiving. Caregivers reported common negative impacts but also beneficial effects, such as feelings of gratification, love, and pride; but there is not know a lot about the role played by these motivational factors.

Finally, we know that there are gender differences that characterize the caregiver perceived burden not only in general terms, but also in regards to the covered role related to the degree of kinship with the recipient. Parents of children with disabilities report more caregiving requirements and stress in all domains compared to parents of children without disability. Mothers generally suffer more stress than fathers do. Stress is negatively associated with informal support for both parents and positively associated with increased caregiving requirements for mothers (Beckman, 1991). However, when the childrentake care of their parents, studies show that males tend to become caregivers only in the absence of females. Generally, males children are more likely to rely on the support of their own spouses; they provide less overall assistance and tend to have less stressful caregiving experiences, independent of their involvement (Horowitz, 1985).

Considering these premises, we hypothesize that:

(H1) Caregivers who take care of people with both pathological conditions experience higher levels of burden and low quality of life, compared to caregivers of patients with only physical disease or mental illness.

(H2) Caregivers who have affective motivation, differently from the sense of duty, have fewer burdens and more quality of life.

(H3) Caregivers in the role of parents have greater resilience compared to caregivers in the role of children, and consequently have fewer burden and higher quality of life.

2. METHOD

2.1. Sample and procedure.

Subjects were recruited from several rehabilitation centers of the provinces of Messina, Catania, Syracuse and Reggio Calabria, from December 2012 to June 2013. Only subjects who signed informed consent for the purposes of research have been tested. The application time required for each participant was between 15-30 min in a single session. Data were anonymized with careful protection of confidentiality.

294 caregivers participated at the study, 206 females (70%) and 88 males (30%) aged between 20 and 80 years, from which 57.5% of them were between 26 to 55 years, 32% were between56 to 70 years, 6.5 % with less than 25 years and 4% with more than 70 years.

Caregivers were assigned to three categories according to the disease nature of their recipient:

(1) Physical diseases (SLA; paralysis, cerebral trauma, permanent anatomic and functional injury);

(2) Mental illness (schizophrenia, obsessive compulsive disorder, mood disorders, anxiety disorders);

(3) Both pathological conditions (Alzheimer's desease, Dementia, Intellectual disability).

These pathological categories derived from the ICD-10 classification and could occur in different degree of severity: mild, moderate and severe.

2.2. Measures.

For the evaluation of the quality of life of caregivers and their burden, they were used the instruments described below.

The informative Questionnaire for Caregivers has been developed within the project of support to caregivers DA.LIA, which was carried out with the contribution of the Ministry for Equal Opportunities in the Region of Emilia Romagna. It consists of 29 items that collect demographic information, concerning the frequency and intensity of the care, motivation at care, knowledge and use of educational, psychological and social support (DA.L.I.A., 2012).

The Italian version of Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI) is a 24-item multi-dimensional questionnaire measuring caregiver burden with 6 subscales: (a) Time Dependence; (b) Developmental; (c) Behaviour; (d) Physical Burden; (e) Social Burden; (f) Emotional Burden. Scores for each item are evaluated using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all disruptive) to 4 (very disruptive). All of the scores on the 24-item scale are summed and a total score >36 indicates a risk of "burning out" whereas scores near or slightly above 24 indicate a need to seek some form of respite care (Novak, & Guest, 1989).

The Quality of Life Index (Spitzer, et al., 1981) is a general QoL index that covers five dimensions: activity, daily living, health, support of family and friends, and outlook. This is one of the earliest QoL instruments to measure activity level, social support, and mental well being. Each item is rated on a three-point scale (0 to 2), with the total scores ranging from 0 to 10. Higher scores reflect better performance (2); lower scores (0) indicate poor quality of life.

3. RESULTS

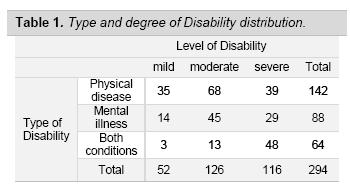

Data were analysed using SPSS version 17.0. In table 1 it is shown the distribution of cases according to the type and degree of the disability reported by caregivers.

H1. Burden and QoL of caregivers of people with physical disease, mental illness, both pathological conditions.

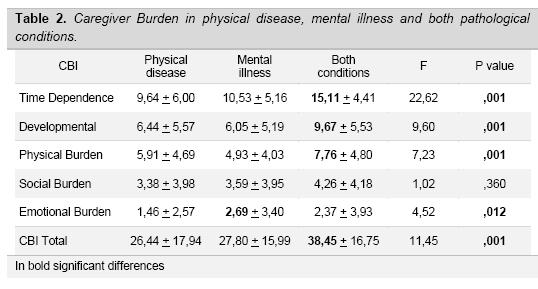

We compared the caregiver burden and quality of life according to the three type of disability of the care-patients (Table 2). From the comparison with ANOVA, significant differences were found in all sub-dimensions of the CBI, except for the Social Burden. Overall, we can observe that when occur both pathological conditions, instead of a single pathology, the caregiver perceives a greater stress condition. However, the most interesting results, concerns the greater weight of mental illness of patients, on the caregiver emotional burden.

In fact, comparing only physical disease vs. mental illness, with the Student's t test, it emerges a single difference: the emotional burden is greater in the case of mental disorders [t (228) = -3.09, p <.002].

Finally, we have identified the subjects that exceeded the cut-off of 36 at the CBI presenting a high risk of burning out; we explored, through Pearson Chi-square, the incidence with some independent variables. In our sample, 95 of 294 subjects were found to be at risk of burning out (32%), of wich 75 women and 20 men: 31 of 95 (32%) face both pathological conditions [χ2 = 9.91, df = 2, observed = 31.0, expected = 20.7, p =.007] and 61 of 95 (64%) judge the degree of the disease as severe [χ2 = 37.9, df = 2, observed = 61.0, expected =37.5, p<.001].

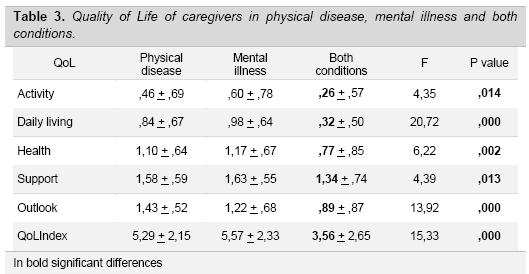

Subsequently, a comparison was made between the three groups in regard to Quality of Life. As presented in Table 3, this analysis showed that all areas of QoL are significantly worse for the group of caregivers who take care of people with both disabilities. In particular, the QoL is impaired in the areas of Activities and Daily Living. On the contrary, the area of Perceived support from relatives is preserved. When we compared only the physical disease vs. mental illness, the unique difference emerged is in the Outlook which is worse (low scores) in the case of mental disorders [t (228) = -2.53, p <.01].

H2. Caregivers burden, Quality of Life and motivation of the care

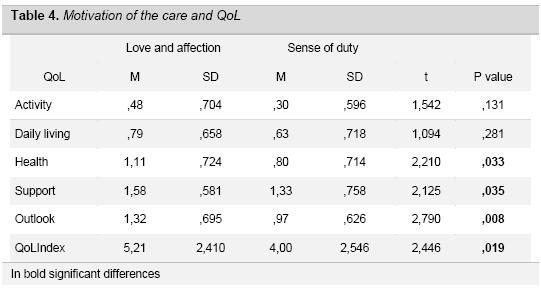

Furthermore, we wanted to determine the main motivation of the care among: (1) love and affection, (2) the sense of duty and responsibility, and (3) there was no other choice. In our sample of 294 caregivers, 224 (76.2%) declare that caregiving is motivated by affection, 34 (11.6%) by the sense of duty and only 14 (4.8%) because there were no alternatives, 22 (7.5%) did not answer. We, therefore, considered only the first two groups (N=258), comparing their burden and quality of life. The third group was excluded because of its small size. The comparison with the Student's t test has identified that caregivers who declare to take care of patient for the sense of duty suffer a greater Social Burden [t (254) = -2.06, p <.05] and a greater Emotional Burden [t (254) = -2.20, p <.05] than caregivers that motivate caring with love and affection.

In regard to QoL, significant differences emerged in three of the five areas examined and in the total index as shown in Table 4. Although the scores are low for both groups, caregivers who take care because of a sense of duty show a worse QoL, especially in the areas of Health, perception of Support, Outlook and general QoL index.

H3. Burden, Quality of Life and social role.

The third hypothesis aimed to examine whether the role of parents (N=83) vs. children (N=100) showed significant differences. The Student's t test showed that there is a greater burden for children who take care of their parents, especially in the time required for assistance [Children: M = 10.6 + 5.9; Parents M = 12.5 + 5.3; t (181) = -2.24, p <.01].

Regarding the caregivers in the role of children, the Quality of Life is worse in the areas: Activity [t (181) = -1.99, p <.05], Health [t (181) = -3.20, p <.001] and Outlook [t (181) = -2.20, p <.05] to that compared of parents in the role of caregivers.

4. DISCUSSION

This study was aimed to investigate the experiences of caregivers who deal with people with chronic physical disease, mental illness, and with both pathological conditions in terms of burden and QoL. Although several studies have shown the correlation between these two aspects of caregiver's experience (Gauthier, et al., 2007; McCullagh, Brigstocke, Donaldson, & Kalra, 2005), there are certain assumptions that need to be discussed.

Chappell (Chappell, & Reid, 2002) argues that the two concepts are distinct: caregiver burden and quality of life are respectively risk or protection factors. The author identified care receiver cognitive status, physical function, and behavioural problems, with hours of caregiving as the primary appraisal variable as primary stressors. Mediators, instead, were perceived as social support like also frequency of getting a break, and hours of formal service use; secondary appraisal was subjective burden. Well-being seems to be directly affected by four variables: perceived social support, burden, self-esteem, and hours of informal care. The finding that perceived social support is strongly related to well-being, but unrelated to burden (Chappell, & Reid, 2002).

With regard to our first hypothesis - (H1) higher levels of burden and low quality of life among caregivers who take care of people with both pathological conditions - the literature, according to our knowledge, lack of an empirical comparison between these conditions. A large number of researches have focused on specific selected samples according to a single pathological type. Thus, the studies carried out on caregivers do not show empirical data on the comparison between these groups.

The results of our study have shown that when caregivers face both pathological conditions they perceive a greater stress (burden) compared to the condition in which the caregiver has to deal with only one pathological condition. In fact, all quality of life areas are significantly worse for the group of caregivers who assists people with both disabilities. In particular, the QoL is impaired in the Activities and Daily Life areas. On the contrary, it is preserved the area of perceived Support from relatives. Besides, when comparing only the physical vs. mental illness, caregivers who take care of mental illness patients show a greater Emotional Burden and a worse Outlook in QoL.

This finding suggests that taking care of a person with psychopathology involves a greater emotional burden and a worse mood for the intervention of relational factors unlike the care of people with exclusively physical disorders despite the burden being similar the quality of life is reduced for both groups. These results are coherent with the study of Provencher (Provencher, 1996) who underlined how the most common negative consequences of caring were the primary caregiver's emotional problems, the disturbance in the caregiver's performance of work, and the disruption in the lives of other adults in the household (Greenberg, Greenley, & Brown, 1997).

The second aspect we aimed to study is related to the differences in burden and quality of life attributable to the motivation of care. Indeed, we have hypothesized a difference in burden and QOL among caregivers who report to take care of patients out of love and affection (affective motivation) and caregivers that involve the sense of duty (moral motivation).

The latter suffer a greater social and emotional burden than those who motivate caregiving with affection. Even in regard to QoL, significant differences in three of the five areas examined emerged. Although the quality of life is poor for both groups, caregivers who report a moral motivation show a worse QoL, especially in the areas: Health, perception of Support, Outlook and general QoL index. Even Caring for an ill family member because of the sense of duty seems to produce negative feelings, which make this task less tolerable. Instead, affection motivation is positively correlated to the level of commitment and negatively correlated to the level of perceived stress (Horowitz, & Shindelman, 1983).

Finally, the third aspect investigated concerns the differences between burden and quality of life that is attributable to the role of parents vs children. In fact, we hypothesized that parents might be more resilient . Data have shown that there is a greater burden for children who take care of their parents, especially in the time required (Time dependence) for the assistance. Also they show a worse QoL in Activities, Health and Outlook areas.

The main motivation of families to provide care for their older relatives is family obligation. Neverthless, when previous relationships are characterized by a flow of services from the older relative to the current caregiver, a motivation of reciprocity intervenes, which resulted to be significantly related to the amount of help given by the caregiver but not to the impact of caregiving (Horowitz, & Shindelman, 1983).

It is possible that these differences in care and assistance between children and parents are due to culturally determined factors. Lee & Sung (Lee, & Sung, 1998) identified culturally specific values, norms, and customs associated with low or high burden. Comparing two group of caregiver of different cultures (American vs. Corean) found that the fewer burden of the Korean caregivers was associated with extended family support and high filial responsibility while that of the American caregivers was related to the use of formal services and high gratification from caregiving.

5. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, when caregivers don't get the help they need, or if they try to do more than they are able, either physically or financially Burnout can occur. Caregivers who are "burned out" may experience fatigue, stress, anxiety, and depression. Many caregivers also feel guilty if they spend time on themselves rather than on their ill or elderly loved ones (El-Nady, 2012).

The symptoms are similar to stress and depression: withdrawal from friends and family, loss of interest in activities previously enjoyed, feeling blue, irritable, hopeless, and helpless, changes in appetite, in weight and/or in sleep patterns, getting more often sick, emotional and physical exhaustion, excessive use of alcohol and/or sleep pill, irritability, and even more, thinking about hurting yourself or other person, in particular the patient (Burnout, 2008).

Quantifying the risk of burnout of caregivers should be a procedure commonly used in clinical practice. The results of the literature highlight the suffering in terms of burden and quality of life of caregivers that all operators should consider in the therapeutic process in order to prevent as far as possible the development of responsive diseases. It is also important, as we have seen, to pay attention and allow caregivers to express their motivations for care and the role of kinship that covers towards the patient in order to use these personal resources in the patient integrate management. The investigation of the motivational aspects of the caregivers and the increased knowledge of the differences between the emotional experience of parents and children can contribute to the definition of more specific psychoeducational interventions and support.

6. REFERENCES

Beckman, P. J. (1991). Comparison of mothers' and fathers' perceptions of the effect of young children with and without disabilities. American journal on mental retardation, 95(5):585-95. [ Links ]

Burnout, R. C. (2008). Caregiving and Burnout. CSA Jourrnal, 40, 32. [ Links ]

Chappell, N. L., & Reid, R. C. (2002). Burden and well-being among caregivers: examining the distinction. The Gerontologist, 42(6), 772-780. [ Links ]

Chio, A., Gauthier, A., Calvo, A., Ghiglione, P., & Mutani, R. (2005). Caregiver burden and patients' perception of being a burden in ALS. Neurology, 64(10), 1780-1782. [ Links ]

Clyburn, L. D., Stones, M. J., Hadjistavropoulos, T., & Tuokko, H. (2000). Predicting caregiver burden and depression in Alzheimer's disease. Journals Of Gerontology Series B, 55(1), S2-S13. [ Links ]

da Silva, G. D. G., Jansen, K., Barbosa, L. P., da Costa Branco, J., Pinheiro, R. T., da Silva Magalhães, P. V., ... & da Silva, R. A. (2013). Burden and related factors in caregivers of young adults presenting bipolar and unipolar mood disorder. International journal of social psychiatry. [ Links ]

D.A.L.I.A. (2012). Informative questionnaire for caregivers. Retrieved from: http://dalia.anzianienonsolo.it/?page_id=59. [ Links ]

Dyck, D. G., Short, R., & Vitaliano, P. P. (1999). Predictors of burden and infectious illness in schizophrenia caregivers. Psychosomatic Medicine, 61(4), 411-419. [ Links ]

El-Nady, M. T. (2012). Relationship between caregivers' burnout and elderly emotional abuse. Scientific Research and Essays, 7(41), 3535-3541. [ Links ]

Foldemo, A., Gullberg, M., Ek, A.C., & Bogren, L. (2005). Quality of life and burden in parents of outpatients with schizophrenia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 40(2), 133-138. [ Links ]

Gauthier, A., Vignola, A., Calvo, A., Cavallo, E., Moglia, C., Sellitti, L., ... & Chio, A. (2007). A longitudinal study on quality of life and depression in ALS patient-caregiver couples. Neurology, 68(12), 923-926. [ Links ]

Glozman, J. M. (2004). Quality of life of caregivers. Neuropsychology Review, 14(4), 183-196. [ Links ]

Goldstein, N. E., Concato, J., Fried, T. R., Kasl, S. V., Johnson-Hurzeler, R., & Bradley, E. H. (2003). Factors associated with caregiver burden among caregivers of terminally ill patients with cancer. Journal of palliative care, 20(1), 38-43. [ Links ]

Grandón, P., Jenaro, C., & Lemos, S. (2008). Primary caregivers of schizophrenia outpatients: Burden and predictor variables. Psychiatry Research, 158(3), 335-343. [ Links ]

Greenberg, J. S., Greenley, J. R., & Brown, R. (1997). Do mental health services reduce distress in families of people with serious mental illness?. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 21 (1), 40-50. [ Links ]

Grover, S., & Dutt, A. (2011). Perceived burden and quality of life of caregivers in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry and clinical neurosciences, 65(5), 416-422. [ Links ]

Grover, S., Chakrabarti, S., Ghormode, D., Dutt, A., Kate, N., & Kulhara, P. (2013). Clinicians' versus caregivers' ratings of burden in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 59(4) [ Links ]

Grunfeld, E., Coyle, D., Whelan, T., Clinch, J., Reyno, L., Earle, C. C., & Glossop, R. (2004). Family caregiver burden: results of a longitudinal study of breast cancer patients and their principal caregivers. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 170(12), 1795-1801. [ Links ]

Hadjistavropoulos, T., Taylor, S., Tuokko, H., & Beattie, B. L. (1994). Neuropsychological deficits, caregivers' perception of deficits and caregiver burden. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 42(3), 308-14. [ Links ]

Hanzawa, S., Bae, J. K., Bae, Y. J., Chae, M. H., Tanaka, H., Nakane, H., & Nakane, Y. (2013). Psychological impact on caregivers traumatized by the violent behavior of a family member with schizophrenia. Asian journal of psychiatry, 6(1), 46-51. [ Links ]

Horowitz, A. (1985). Sons and daughters as caregivers to older parents: Differences in role performance and consequences. The Gerontologist, 25(6), 612-617. [ Links ]

Horowitz, A., & Shindelman, L. W. (1983). Reciprocity and affection: Past influences on current caregiving. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 5(3), 5-20. [ Links ]

Hou, S. Y., Ke, C. L. K., Su, Y. C., & Huang, C. J. (2008). Exploring the burden of the primary family caregivers of schizophrenia patients in Taiwan. Psychiatry and clinical neurosciences, 62(5), 508-514. [ Links ]

Lauber, C., Eichenberger, A., Luginbúhl, P., Keller, C., & Rõssler, W. (2003). Determinants of burden in caregivers of patients with exacerbating schizophrenia. European Psychiatry, 18(6), 285-289. [ Links ]

Lautenschlager N.T., Kurz, A.F,. Loi, S., & Cramer, B. (2013). Personality of mental health caregivers. Curr Opin Psychiatry, 26, 97-101. [ Links ]

Lee, Y. R., & Sung, K. T. (1998). Cultural influences on caregiving burden: Cases of Koreans and Americans. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 46(2), 125-141. [ Links ]

Levine, S. A., & Barry, P. P. (2003). Home care. In Geriatric Medicine. Springer New York, 121-131. [ Links ]

Marsh, N. V., Kersel, D. A., Havill, J. H., & Sleigh, J. W. (1998). Caregiver burden at 1 year following severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury, 12(12), 1045-1059. [ Links ]

Martens, L., & Addington, J. (2001). The psychological well-being of family members of individuals with schizophrenia. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 36(3), 128-133. [ Links ]

McCullagh, E., Brigstocke, G., Donaldson, N., & Kalra, L. (2005). Determinants of caregiving burden and quality of life in caregivers of stroke patients. Stroke, 36(10), 2181-2186. [ Links ]

Morimoto, T., Schreiner, A. S., & Asano, H. (2003). Caregiver burden and health-related quality of life among Japanese stroke caregivers. Age and Ageing, 32(2), 218-223. [ Links ]

Novak, M., & Guest, C. (1989). Application of a multidimensional caregiver burden inventory. The gerontologist, 29(6), 798-803. [ Links ]

Ohaeri, J. U. (2003). The burden of caregiving in families with a mental illness: a review of 2002. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 16(4), 457-465. [ Links ]

Papastavrou, E., Kalokerinou, A., Papacostas, S. S., Tsangari, H., & Sourtzi, P. (2007). Caring for a relative with dementia: family caregiver burden. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 58(5), 446-457. [ Links ]

Provencher, H. L. (1996). Objective burden among primary caregivers of persons with chronic schizophrenia. Journal of psychiatric and mental health nursing, 3(3), 181-187. [ Links ]

Razani, J., Kakos, B., Orieta-Barbalace, C., Wong, J. T., Casas, R., Lu, P., ... & Josephson, K. (2007). Predicting caregiver burden from daily functional abilities of patients with mild dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 55(9), 1415-1420. [ Links ]

Riedijk, S. R., De Vugt, M. E., Duivenvoorden, H. J., Niermeijer, M. F., Van Swieten, J. C., Verhey, F. R. J., & Tibben, A. (2006). Caregiver burden, health-related quality of life and coping in dementia caregivers: a comparison of frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Dementia and geriatric cognitive disorders, 22(5-6), 405-412. [ Links ]

Saunders, J. C. (2003). Families living with severe mental illness: A literature review. Issues in mental health nursing, 24(2), 175-198. [ Links ]

Schulz, R., & Beach, S. R. (1999). Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association, 282(23), 2215-2219. [ Links ]

Spitzer, W. O., Dobson, A. J., Hall, J., Chesterman, E., Levi, J., Shepherd, R., ... & Catchlove, B. R. (1981). Measuring the quality of life of cancer patients: a concise QL-index for use by physicians. Journal of chronic diseases, 34(12), 585-597. [ Links ]

Steadman, P. L., Tremont, G., & Davis, J. D. (2007). Premorbid relationship satisfaction and caregiver burden in dementia caregivers. Journal of geriatric psychiatry and neurology, 20(2), 115-119. [ Links ]

Thomas, P., Lalloué, F., Preux, P. M., Hazif-Thomas, C., Pariel, S., Inscale, R., ... & Clément, J. P (2006). Dementia patients caregivers quality of life: the PIXEL study. International journal of geriatric psychiatry, 21 (1), 50-56. [ Links ]

Torres, A. R., Hoff, N. T., Padovani, C. R., & Ramos-Cerqueira, A. T. D. A. (2012). Dimensional analysis of burden in family caregivers of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry and clinical neurosciences, 66(5), 432-441. [ Links ]

Veltman, A., Cameron, J. I., & Stewart, D. E. (2002). The experience of providing care to relatives with chronic mental illness. The Journal of nervous and mental disease, 190(2), 108-114. [ Links ]

Zendjidjian, X., Richieri, R., Adida, M., Limousin, S., Gaubert, N., Parola, N., ... & Boyer, L. (2012). Quality of life among caregivers of individuals with affective disorders. Journal of affective disorders, 136(3), 660-665. [ Links ]