Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

International Journal of Psychological Research

Print version ISSN 2011-2084

int.j.psychol.res. vol.7 no.1 Medellín Jan./June 2014

Psychosocial Adolescent Psychosocial Adjustment in Brazil - Perception of Parenting Style, Stressful Events and Violence

Ajuste Psicosocial de los Adolescentes en Brasil - La Percepción del Estilo Parental, Eventos Estresantes y la Violencia

Silvia Pereira da Cruz Benettia,b,*, Cristian Schwartza,b, Glaucia Roth Soaresa,b, Francis Macarenaa,b and Marcos Pascoal Pattussia,b

a Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos, UNISINOS, São Leopoldo, RS, Brazil.

b Conselho Nacional de Educação e Pesquisa- CNPq, Brazil.

* Corresponding author: Silvia Pereira da Cruz Benetti, Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos, UNISINOS, São Leopoldo, RS, Brazil. Rua Riveira, 150/301. Porto Alegre. RS. 90670-160. Brazil. Email address: sbenetti@unisinos.br

ARTICLE INFO

Article history: Received: 29-08-2013 Revised: 06-12-2013 Accepted: 15-02-2014

ABSTRACT

The objective of this study was to investigate the association between measures of exposure to violence, stressful events, family socialization practices, and demographic characteristics in a group of adolescents from a Southern region of Brazil. Three hundred adolescents were investigated in a case-control study. The results showed that adolescents with emotional and behavioral problems had significant higher stressful events, violence exposure, and negative parental practices, compared with controls. However, exposure to violence was the most deteriorating condition associated with the adolescents' clinical internalization and externalization behaviors. Findings suggest the benefit of targeting actions geared to strengthen the quality of family interactions as well as to implement preventive programs to reduce community violence impact and to enhance support in the community.

Key words: Adolescence, mental health, violence, family relations.

RESUMEN

El objetivo de este estudio fue investigar la asociación entre las medidas de exposición a la violencia, los acontecimientos estresantes, prácticas de socialización familiar y las características demográficas de un grupo de adolescentes de la región sur de Brasil. Trescientos adolescentes fueron investigados en un estudio caso-control. Los resultados mostraron que los adolescentes con problemas emocionales y de comportamiento tuvieron los acontecimientos significativos mayor estrés, exposición a la violencia y las prácticas negativas de los padres, en comparación con los controles. Sin embargo, la exposición a la violencia era la condición clínica más deteriorada asociada con la internalización de los adolescentes y los comportamientos de exteriorización. Los resultados sugieren el beneficio de acciones orientadas a fortalecer la calidad de las interacciones familiares, así como la implementación de programas de prevención para reducir la violencia y ampliar el apoyo en la comunidad.

Palabras clave: Adolescencia, salud mental, violencia, relaciones familiares.

1. INTRODUCTION

Exposure to stressful events and violence has been extensively associated with deleterious outcomes in children and adolescents' development (Margolin, 2005; Mrug & Windle, 2010; Ribeiro, Andreoli, Ferri, Prince, & Mari, 2009). Violence disrupts child development both at the level of clinical manifestations as well as in more subtle behaviors regarding feelings of safety, trust in others, and school performance, either when witnessing or being the victim of a violent act (Lambert, Boyd, Cammack, & Lalongo, 2012; Margolin, 2005). In this sense, exposure to violence at home and in the community enhances the chances of poor psychosocial adjustment, increasing the chances of manifesting internalizing and externalizing problems (Mrug & Windle, 2010), mental health problems, drug abuse, delinquency (Herrenkohl, Hong, Klika, Herrenkohl, & Russo, 2013; Sperry & Widom, 2013) along children and adolescents' development. Besides, experiencing stressful events or adversities in childhood and adolescence has also been associated with poor psychological adjustment and mental health problems along the lifespan, especially situations involving abuse and family negative events (Ribeiro et al., 2013).

Based on a sample of 2362 interviews from the Mexican National Comorbidity Survey (M-NCS), Benjet, Borges, and Medina-Mora (2010) identified that among 12 adverse situations in childhood, family dysfunction and abuse were the strongest and most consistent predictors of four classes of psychopathologies (mood, anxiety, substance use and externalizing) investigated. The negative effects were documented in almost over all three life course stages of the sample (childhood, adolescence and adulthood). These results ratifies the importance of family interaction and socialization practices as basic factors related to positive outcomes in development, especially considering those practices which ensure positive relationships with parents. In some cases, positive interactions might even act as protective factors to the effects of violence exposure, principally the relationship established with the mother (Kennedy, Bybee, Sullivan, & Greeson, 2010).

In Brazil, children's poor psychological outcomes have also been associated with contextual, family and individual factors (Sá, Bordin, & Martin, Paula, 2010; Ribeiro et al., 2013), such as unfavorable economic conditions; violence; parental mental health problems, especially maternal problems (Fleitlich & Goodman, 2001); male gender; harsh parental practices (Vitolo, Fleitlich-Bilyk, Goodman & Bordin, 2005); relationships problems; low self-esteem; low life satisfaction; and school difficulties (Avanci, Assis, Oliveira, & Pires, 2009). In spite of the importance of the topic, there is a need to improve the number of studies aimed at identifying the characteristics and factors associated with psychological outcomes and mental health problems in Brazilian children and adolescents to ensure valid information on the subject and to improve the development of adequate practices, programs and policies (Andrade et al., 2012).

The objective of this article was to identify potential risk factors related to the emotional and behavioral problems in adolescents from a city in the southern part of Brazil. Therefore, based on the need for reliable information about psychological adjustment and internalizing and externalizing outcomes, we developed a case-control study to investigate the association of exposure to violence, stressful events, family socialization practices and demographic characteristics in a group of adolescents with emotional and behavioral problems.

2. METHOD

2.1. Study population

The study was conducted in São Leopoldo, a city of the Metropolitan area of Porto Alegre, State of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. According to the last census, the city had 214,087 inhabitants, 36,281 of whom were 10 to 19 years of age in 2010 (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística [IBGE], 2012).

2.2. Study design

This study was a case-control study nested in a cross-sectional survey. To identity cases and controls, we initially conducted a survey in the city's three largest schools in 2010. The schools were located in the central area and received students from all districts. Cases were defined as those adolescents presenting a clinical diagnosis according to the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach, 1991). Controls were those adolescents not classified as clinical, and they were matched to the cases based on their sex, age and school class.

2.3. Sampling

The sample size was calculated using the Epi-Info 6.0 program. A prevalence of mental health problems in 20% of the population (non-clinical group) was considered, and a control rate of 3:1, power of 80%, a 95% confidence interval, and a prevalence of 37.3% in the clinical group were calculated. The final sample consisted of 300 adolescents, including 64 clinical cases and 236 controls. Following this step, all the clinical cases were matched based on their sex, age and school class.

2.4. Procedure

The school board of the city was initially contacted to request authorization to conduct the study. Three of the Middle and High Schools located in the central area of the city received students from all districts of the town. Family income from these districts varied from low to middle class. Each student received a letter explaining the study along with an Informed Consent Form that needed to be signed by the parents or the responsible adult. The classes had an average of 30 students. Up to 5 students in each class did not participate in the study due to no authorization from parents or to not being present on the day the data were collected. In the first school, 70 students were investigated, followed by 150 from the second and 150 from the third school.

All the instruments were answered individually by the adolescents in the classroom; they responded under the supervision of previously trained research assistants. Data were collected in two separate sessions. In the first session, the adolescents filled out a sociodemographic questionnaire that included questions about their age, their education, their parents' education, and the professional characteristics of their parents. The CBCL (Youth Self-Report version, Achenbach, 1991) was also answered by the adolescents in this session. In the second session, all the other questionnaires were applied. From this initial group, we selected the clinical cases classified by the CBCL; a total of 64 cases which were matched according to age, sex and school class. Finally, the clinical cases were referred to the University Clinic after consulting with the school board and their families. To have parsimony, only the total scores were used. Subscale results are available under request. Except for the CBCL, the above mentioned scales had their items summed and categorized in three equally sized groups based on the tertiles of the distribution.

2.5. Instruments

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL, Achenbach, 1991) consists of a standardized report on the children's social competence, and emotional and behavioral problems in the previous months, as reported by parents or parent surrogates, teachers and adolescents (11-18 years old) respectively. In the present study, the Youth Self-Report version of the CBCL used was the YSR/11-18, which was completed by the adolescents. Problem behaviors were scored on syndromes (Withdrawn, Somatic Complaints, Anxious/Depressed, Social Problems, Thought Problems, Attention Problems, Delinquent Behavior, and Aggressive Behavior) that were further summarized into Internalizing Problems (Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed and Somatic Complaints scales), Externalizing Problems (of Rule-Breaking Behavior and Aggressive Behavior scales) or into Total Problems (sum of all items). In Brazil, the CBCL has been validated by Bordin, Mari and Caeiro (1995). T Scores less than 67 were classified as non-clinical; T Scores in the range of 6770 were Borderline, and T Scores greater than 70 were Clinical.

Screening Survey of Children's Exposure to Community Violence (Richters, & Martinez, 1983). This survey is a self-administered questionnaire that was developed by the National Institute of Mental Health of the United States to identify children and adolescents who had been exposed to community violence. The Screening Survey includes 49 questions that identify situations of community violence (drug exposure, assault related events, homicide events), physical violence, sexual violence, and family violence. The exposure to violence was categorized as being a victim, being a witness, or knowing someone who had been a victim of a violent act. Each of the specific situations was answered as "true" or "false" depending on whether it had been experienced. In this study, all episodes of witnessing community violence were summed, resulting in the variable Community Violence Exposure. Additionally, we computed the score for the total episodes of violence exposure; in this case, all the situations were summed (community, physical, sexual and family violence), resulting in the variable Total Violence Exposure. Analysis of the internal validity of the instrument resulted in a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.89.

Medical Outcomes Study (MOS, Social Support Survey): This 19 item survey was developed to assess the perceptions of the availability of the following different functional forms of support: emotional, informational, tangible, affectionate, and positive social interaction (Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991). Emotional support contained 4 items measuring the expression of positive affect, empathetic understanding, and encouragement feeling expressions. Information support contained 4 items measuring the provisions of advice, information, guidance or feedback. Tangible support contained 4 items measuring the offering of material aid or behavioral assistance. Affectionate support contained 3 items measuring the expressions of love and affection. Positive social interaction contained 4 items measuring the availability of other persons to do fun things with the adolescent. The following responses options were provided: none of the time (1), a little of the time (2), some of the time (3), most of the time (4), and all of the time (5), with higher scores indicating a better perception of social support. In Brazil, the survey was adapted by Chor et.al. (2001). In the present study, the Cronbach's alpha was 0.87.

Stressful Life Events (Kristensen, Leon, D'Incao, & Dell'Aglio, 2005). This instrument was developed to identity the frequency and the intensity of the impact of traumatic life events in different domains (social, family, personal, and sexual). It consisted of 64 items that were selected as an affirmative or negative option followed by a Likert scale of five points (5 being an intense event). In this study, the Cronbach's alpha was 0.92.

Parenting Style Inventory (Gomide, 2006) consisted of 42 items describing the following parental practices: positive involvement, and prosocial behavior, inconsistent discipline, neglect, negative involvement and physical abuse. The total scores were classified into the following three categories of parenting: poor, regular and good. The Cronbach's alpha for the paternal parenting scale was 0.79, the maternal scale was a 0.92, and the total scale was 0.86.

2.6. Data analysis

The data analysis was conducted using the Stata 11.0 program. To assess the distribution of cases and controls according to the independent variables, a Chi-square test was used. To obtain the unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios, a conditional logistic regression was adopted. The backward selection procedure was adopted in the multivariable model. It started with fitting a model with all the variables. The least significant variable was then dropped as long as it was not significant at the 5% level. The procedure was continued by successively re-fitting the reduced models and applying the same rule until all the remaining variables were statistically significant. The likelihood ratio test was used to test and showed the adequacy of the final model.

2.7. Ethics

Regional and Health authorities and the Bioethics Committees of the Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos, Brazil, all approved the study protocol survey. Each student and parent signed an informed written consent. After consulting with the school board and families, participants classified as clinical cases were referred to the University Clinic.

3. RESULTS

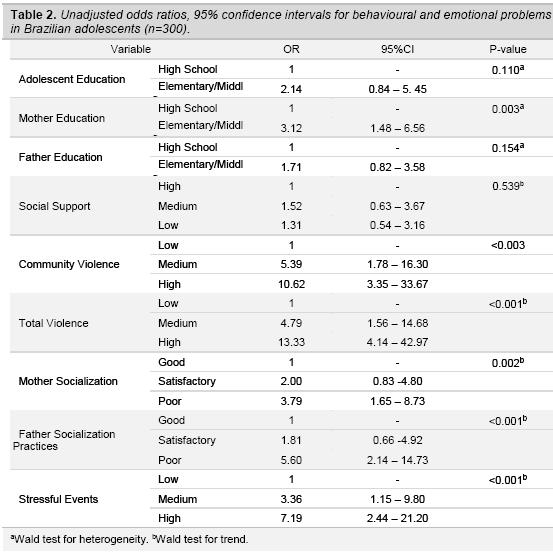

Of the 390 adolescents who participated in the survey, 90 cases were excluded due to the lack of eligible controls for their age, sex and school class. A total of 64 cases and 236 controls took part in the study. The main reasons for the losses were lack of a match and refusals. The cases were similar to the controls in terms of age, adolescent education and social support. The proportion of adolescents reporting emotional or behavioral problems was significantly higher considering the unfavorable categories of maternal education, total violence exposure, maternal and paternal socialization practices, and stressful events variables (Table 1). Social support was not significantly different between the cases and the controls.

3.1. Logistical analysis

Compared to the favorable reference categories, the possibilities of reporting behavioral and emotional problems were higher in adolescents whose mothers had low education, in those exposed to violence, with poor maternal and paternal practices, and in those reporting more stressful events (Table 2). In the same line, violent experiences related to community violence exposure (drug exposure, assault, homicide) increased 10 times the chances of developing emotional disorders (OR=10. 62 IC95%: 3.35-35.68; P=0.000). Analysis of each category of family, sexual, and physically violent events did not indicate a significant difference between cases and controls. On the other hand, total exposure to violence, in all areas including the community, family, sexual, and physically violent events, increased 13 times the possibilities of a clinical diagnosis (OR=13. 33 IC95%: 4.13-42.77; P=0.000).

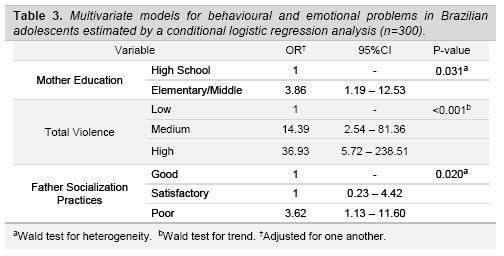

In the final adjusted model (Table 3), total violence exposure, maternal education and paternal practices remained associated with the outcome. However, total violence exposure showed the strongest effect. The odds of reporting behavioral and emotional problems among adolescents reporting high exposure to violence were 37 times the odds of those reporting exposure to low levels of violence. Similarly, higher odds were found in adolescents from families whose mother had low education and father had poor paternal practices, compared to those from more favorable characteristics (Table 2).

4. DISCUSSION

In the last decades, several studies have identified distinct dimensions of human context that have been associated with child and adolescent psychopathology (Kieling et al., 2011). Ranging from social and economic circumstances to family and individual characteristics in a perspective that encompasses the interaction of these factors as potential underlying causes of emotional disorders, researchers have strongly indicated the necessity of promoting actions geared toward both prevention and intervention of mental health problems in these age groups.

Considering these aspects, the results of the present study will hopefully contribute to a better understanding of the consequences of risk factors for emotional and behavioral problems in children and adolescents in Brazil.

Based on a sample of adolescents from the southern part of Brazil, the strength of the study was in the design, since it contained instruments that provided the necessary information for comparison in a case-control study. This design attempted to address the weight of individual characteristics and family and community factors related to adversity to determine the importance of each one of these circumstances in youth adjustment.

In the present study, a comparison between cases and controls showed that the adolescents with emotional and behavioral problems had significantly higher stressful events, violence exposure, and negative parental practices, compared with the control adolescents. Interestingly, the two groups did not differ in relation to their perceived social support and positive parental practices. These last results might indicate that despite the presence of perceived support and family interactions associated to good parenting, the simultaneous presence of violence either in the family or the social context had a more damaging effect on mental health. In this way, violent events surpassed the protective effects of positive interactions in the social and family contexts.

Although distinct factors were identified as contributing to emotional and behavioral problems, maternal low school level, poor maternal and paternal practices, and stressful life events, exposure to violence, both community violence and the total episodes of violence experienced were the most deteriorating conditions associated with the adolescents' clinical internalizations and externalization behaviors; community violence exposure was significantly associated with the clinical emotional and behavioral problems in adolescents. However, when specific violent situations related to events linked to more immediate and personal domains were added to the community violence variable, such as physical violence, family violence, and sexual violence, the chances of presenting a clinical diagnosis were thirty times higher. Therefore, experiencing violence in the community context as well as in the immediate context of the family were the variables with the strongest effect on the quality of psychosocial adjustment. Although caution must be taken when interpreting this result, the propensity of the association indicated that community violence exposure was damaging to mental health, but when the adolescents were also faced with adversities present in their immediate environment, where close relationships were developed and fostered, the negative consequences were dramatic.

On the other hand, Mrug and Windle (2010) in a study of a community sample of 603 early adolescents on the impact of violence exposure across home, school, and community on internalizing and externalizing problems, verified that exposure to violence at home and at school had more deleterious consequences than community exposure. Although this finding points to distinct effects of violence exposure, it also indicates the importance of investigating the specifics ways distinct contexts affect individuals, since in the present study the cumulative effect of violence exposure had the more damaging effect.

The implications of the results of this study in terms of the need to develop initiatives in different levels of interventions are clear. Societies facing the challenge of assisting families that are exposed to violent environments need to acknowledge the importance of addressing and targeting social programs to help these families. Ribeiro et al. (2009), in a study of the epidemiological evidence on the prevalence of exposure to violence and its association to mental health problems in low and middle-income countries, verified that the frequency of violent acts is high among these populations. Regarding children and adolescents, domestic violence related to harsh paternal discipline practices is the category to which children are often exposed, especially among families in vulnerable groups.

In our findings, the negative consequences of negative paternal practices indicated that family relationships, and, most importantly, male involvement with children socialization, should be the targets of political practices geared to ensure that the family, as the first context of interactions, must be a place where healthy, loving and caring practices are the rule. However, these ties are easily strained when one faces impoverished circumstances, unhealthy living conditions and poor life perspectives, all factors that can undermine the capacity of promoting the development of both the individual as well as of the communities where they live. In this sense, adolescents with mothers with low levels of education were more vulnerable to mental problems. Considering gender aspects associated with Brazilian culture, this finding may suggest that social restrictions and access to financial independence place women in roles that are ineffective in providing protective socialization practices related to a positive psychological outcome in their children. Undoubtedly, this topic must be placed as a priority agenda of future research as in cultures with similar characteristics to develop parenting programs sensitive to the families' needs (Burke, Brennan, & Cann, 2012).

5. LIMITATIONS OF THE RESEARCH

Finally, some limitations of the present study need to be addressed. The findings were limited to a particular group of adolescents from a specific region of Brazil. Additionally, the data collection method included information provided only by the adolescent. Studies investigating different regions as well as considering different sources of data are suggested.

6. CONCLUSION

Violence victimization among adolescents in various settings, such as family, school and community, was the most important factor related to poor psychosocial adjustment in adolescence. Both situations involving community violence and violent acts present in the immediate context of the adolescents' lives significantly increased their internalizing and externalizing problems. Nonetheless, stressful events, and poor maternal and paternal negative socialization practices were also adverse factors. However, exposure to violence in different domains, negative father interactions and mothers with low level of education were the most important factors associated with the adolescents' mental health problems. These results indicate the great benefit of targeting actions geared to improve family relations, and they confirm the need to strengthen the quality of both family interactions and community support.

7. REFERENCES

Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Integrative guide for the CBCL/4-18, YSR, and TRF profiles. Burlington: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont. [ Links ]

Andrade, S. S. C., Yokota, R. T. C., Sá, N. N. B., Silva, M. M. A., Araújo, W. N., Mascarenhas, M. D. M., & Malta, D. C. (2012). Association between physical violence, consumption of alcohol and other drugs, and bullying among Brazilian adolescents. Caderno de Saúde Pública, 28,1725-1736. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2012000900011. [ Links ]

Avanci, J., Assis, S., Oliveira. R., & Pires, T. (2009). Quando a convivência com a violência aproxima a criança do comportamento depressivo. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 14, 383-394. [ Links ]

Benjet, C., Borges, G., & Medina-Mora, M. E. (2010). Chronic childhood adversity and onset of psychopathology during three life stages: Childhood, adolescence and adulthood. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 44, 732-740. [ Links ]

Bordin, I. A. S, Mari, J. J., & Caeiro, M. F. (1995). Validação da versão brasileira do Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (Inventário de Comportamentos da Infância e Adolescência): dados preliminares. Revista ABP-APAL, 17, 55-66. [ Links ]

Burke, K., Brennan, L., & Cann, W. (2012). Promoting protective factors for young adolescents: ABCD Parenting Young Adolescents Program randomized controlled trial. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 1315-1328. http://dx.doi.org.ez101.periodicos.capes.gov.br/10.1016/j.adolescence. [ Links ]

Chor, D., Griep, R. H., Lopes, C. S., & Faerstein, E. (2001). Social network and social support measures from the pró-saúde study: Pre-tests and a pilot study. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 17(4), 887-896. [ Links ]

Fleitlich, B. W., & Goodman, R. (2001). Social factors associated with child mental health problems in Brazil: cross sectional survey. British Medical Journal, 323, 599-600. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7313.599. [ Links ]

Gomide, P. I. C., Salvo, C. G., Pinheiro, D. P. N., & Sabbag, G. M. (2005). Correlação entre práticas educativas, depressão, stress e habilidades sociais. Psico-USF, 10(2), 169178. [ Links ]

Herrenkohl, T. I., Hong, S., Klika, J. B., Herrenkohl, R. C., & Russo, M. J. (2013). Developmental impacts of child abuse and neglect related to adult mental health, substance use, and physical health. Journal of Family Violence, 28, 2,191-199. [ Links ]

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). IBGE cidades. Retrieved from http://www.ibge.gov.br/cidadesat/topwindow.htm?1. [ Links ]

Kennedy, A. C., Bybee, D., Sullivan, C. M., & Greeson, M. (2010). The impact of family and community violence on children's depression gender. Journal of Family Psychology, 24, 97-207. [ Links ]

Kieling, C., Baker-Henningham, H., Belfer, M., Conti, G., Ertem, I., Omigbodun, O., Rahman, A. (2011). Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. The Lancet, 378, 1515-1525. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60827-1. [ Links ]

Kristensen, C., Leon, J., D'Incao, D., & Dell'Aglio, D. (2005). Análise da frequência e do impacto de eventos estressores em uma amostra de adolescentes. Interação em Psicologia 8(1). Retrieved from http://ojs.c3sl.ufpr.br/ojs2/index.php/psicologia/article/view/3238/2599. [ Links ]

Lambert, S. F., Boyd, R. C., Cammack, N. L., & Lalongo, N. S. (2012). Relationship proximity to victims of witnessed community violence: associations with adolescent internalizing and externalizing behaviors. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82, 1-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01135.x. [ Links ]

Margolin, G. (2005). Children's exposure to violence: exploring developmental pathways to diverse outcomes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20, 72-81. doi:10.1177/0886260504268371. [ Links ]

Mrug, S., & Windle, M. (2010). Prospective effects of violence exposure across multiple contexts on early adolescents' internalizing and externalizing problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 51, 953-961. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02222.x. [ Links ]

Ribeiro, W. S., Andreoli, S. B., Ferri, C. P., Prince, M., & Mari, J. J. (2009). Exposure to violence and mental health problems in low and middle-income countries: a literature review. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 31, S2, 49-57. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1516-44462009000600003. [ Links ]

Ribeiro, W. S., Mari, J. J., Quintana, M. I., Dewey, M. E., Evans-Lacko S.,...Andreoli, S. B. (2013). The impact of epidemic violence on the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro,Brazil. PLoSONE 8(5): e63545. doi:1 0.1371/journal.pone.0063545. [ Links ]

Richters, J. E., & Martinez, P. (1993). The NIMH community violence project: I. children as victims of and witness to violence. Psychiatry,56, 7-21. [ Links ]

Sherbourne, C.D., Stewart, A.L. (1991). The MOS Social Support Survey. Social Science and Medicine, 32 (6), 705-14. [ Links ]

Sperry, D. M., & Widom, C. S. (2013). Child abuse and neglect, social support, and psychopathology in adulthood: A prospective investigation. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(6), 415-425. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.02.006. [ Links ]

Sá, D. G. F., Bordin, I. A, Martin, D., & Paula, C. S. (2010). Fatores de risco para problemas de saúde mental na infância/adolescência. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 26, 643-652. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S010237722010000400008. [ Links ]

Vitolo, Y. L. C., Fleitlich-Bilyk, B., Goodman, R., & Bordin, I. A. S. (2005). Crenças e atitudes educativas dos pais e problemas de saúde mental em escolares. Revista de Saúde Pública, 39, 716-724. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-89102005000500004. [ Links ]