Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

International Journal of Psychological Research

versão impressa ISSN 2011-2084

int.j.psychol.res. vol.8 no.1 Medellín jan./jun. 2015

The Effect of Intergroup Threat and Social Identity Salience on the Belief in Conspiracy Theories over Terrorism in Indonesia: Collective Angst as a Mediator

El efecto de la amenaza intergrupal y la identidad social saliente en la creencia en teorías de conspiración sobre el terrorismo en Indonesia: la angustia colectiva como un mediador

Ali Mashuria,b,* and Esti Zaduqistic

a Department of Psychology, University of Brawijaya, Indonesia.

b Department of Social and Organizational Psychology, VU Universimy Amsdercdam, Netreaands.

c Education department, State College of Isalmic Studies Pekalongan STAIN, Indonesia.

* Corresponding author: Ali Mashuri, Department of Psychology, University of Brawijaya, Malang, Indonesia.Email address: alimashuri76@ub.ac.id

Article history: Received: 14-04-2014 Revised: 10-08-2014 Accepted: 28-11-2014

ABSTRACT

The present study tested how intergroup threat (high versus low) and social identity as a Muslim (salient versus non-salient) affected belief in conspiracy theories. Data among Indonesian Muslim students (N = 139) from this study demonstrated that intergroup threat and social identity salience interacted to influence belief in conspiracy theories. High intergroup threat triggered greater belief in conspiracy theories than low intergroup threat, more prominently in the condition in which participants' Muslim identity was made salient. Collective angst also proved to mediate the effect of intergroup threat on the belief. However, in line with the prediction, evidence of this mediation effect of collective angst was only on the salient social identity condition. Discussions on these research findings build on both theoretical and practical implications.

Key words: belief in conspiracy theories; collective angst; intergroup threat; social identity salience; terrorism in Indonesia.

RESUMEN

El presente estudio examinó cómo la amenaza intergrupal (alta versus baja) y la identidad social como musulmán (saliente versus no saliente), afecta la creencia en teorías de conspiración. Los datos entre los estudiantes Musulmanes de Indonesia en este estudio, (N = 139) mostraron que la amenaza intergrupal y la saliencia de la identidad social, interactúan para influenciar creencias en teorías de conspiración. La amenaza intergrupal alta produjo mayor creencia en teorías de conspiración en comparación con la amenaza intergrupal baja, esta condición se presentó de manera más prominente en los participantes en donde la identidad musulmana se hizo saliente. La angustia colectiva también contribuyo a mediar el efecto de la amenaza intergrupal en la creencia; no obstante, de acuerdo con la predicción, la evidencia de este efecto de mediación de la angustia colectiva fue sólo con la condición de identidad social saliente. Las discusiones sobre estos resultados de la investigación se basan en dos implicaciones teóricas y prácticas.

Palabras clave: creencia en teorías de conspiración, angustia colectiva, amenaza intergrupal, saliencia de identidad social; terrorismo en Indonesia.

1. INTRODUCTION

There is now a well-documented literature on how multifarious personality characteristics shed light on people's proclivity towards belief in conspiracy theories (see Swami, 2012 for the review). However, very little is known about the effect of situational factors on belief in conspiracy theories (but see van Prooijen & Jostmann, 2013). In the spirit to fill this gap, this study aimed at explaining the belief in conspiracy theories on the basis of two situational factors: intergroup threat and social identity salience. We also propose a group-based variable of collective angst as a mediator to provide an answer as to why intergroup threat and social identity salience may impact belief in conspiracy theories. The contextual background used to examine these situational determinants of the belief in conspiracy theories is terrorism in Indonesia, which is up to date and even timely a topic that becomes one of the Indonesian government's serious concerns (Arnaz & Marhaenjati, 2013).

At an intergroup level, conspiracy theories imply categorization of an out-group and an in-group, wherein the out-group plays a role as the actors of the conspiracy theories whereas the in-group plays a role as the believers. In this perspective of intergroup relations, conspiracy theories depict the out-group as a collective enemy who aims at dominating the in-group through hidden activities (Kofta & Sedek, 2005). The content of conspiracy beliefs is specific, in the form of framing an out-group as a dangerous, powerful, or deceptive adversary (Kofta, 1995). As contended by Sapountzis and Condor (2013), belief in conspiracy theories signifies a dualistic account of intergroup relations with which members of the in-group are apt to ascribe any events to a direct design on the part of a powerful out-group. In support of this notion, Imhoff and Bruder (2014) recently reported that participants' belief in conspiracy theories related to their negative stereotyping against powerful out-groups regarded as less likable and more threatening.

Some studies have indeed uncovered that in-group members are vulnerable to have negative stereotyping against out-group members more particularly in the condition in which the first deem the second as threatening their existence (e.g., Branscombe & Wann, 1992; Mullen, Brown, & Smith, 1992; Stephan, Diaz-Loving, & Duran, 2000). This argumentation is in line with a meta-analysis study by Riek, Mania, and Gaertner (2006) reporting that intergroup threats gave rise to negative out-group attitudes. Stephan and Stephan (1996, 2000) differentiated realistic threat and symbolic threat. Realistic threat denotes a threat to the sustainability of in-group's economic and political existence. Symbolic threat is a threat originating from perceived intergroup differences in norms, values, and beliefs. In-group members may perceive an out-group as posing a threat to socio-cultural identity if the worldviews of the out-group are different from those of the in-group.

Prior empirical studies that have examined the role of intergroup threats in molding negative intergroup attitude in terms of belief in conspiracy theories are still relatively unexplored. However, Kofta, Sedek, and Slawuta (2011) pioneered the study on the role of intergroup threat in affecting the belief in conspiracy theories. They found that that a realistic threat portraying Jewish people as undermining Poland's group power triggered the Polish participants to believe in theories that the Jews have conspired to dominate the world. In the context of Muslims in Islamic countries, some studies have revealed several factors that catalyze a realistic threat among people in these countries. These factors are a striking gap in terms of economic prosperity between the Western and Muslim countries, dominance of democracy as a secular political system worldwide, and a foreign policy perceived as against Muslim such as the occupation of Palestine by Israel, the U.S' invasions in Iraq and Afghanistan (Castells, 2011; Fair & Shepherd, 2006; Moghaddam, 2008; Putra & Sukabdi, 2013; Robison, Crenshaw & Jenkins, 2006). Among some Muslims in Indonesia, such Western political and economic dominance incinerates a sense of defeat, which provokes the belief that the West has conspired to debilitate Islam and Muslims (Azra, 2000; 2006, Khisbiyah, 2009; Solahuddin, 2013; Suciu, 2008).

Some Muslims also perceive that Western countries represent a catalyst of modernization and globalization, which pose a symbolic threat signifying a form of neocolonialism that supplants Muslim's religious and cultural identity (Esposito, 2000). As a result, some Muslims interpret modernization and globalization as an attempt to homogenize the world that undermines Islamic identity, which has aroused anxiety, suspicion, and opposition in the Islamic countries (Moten, 2005). In support of this argumentation, Mashuri and Zaduqisti (2014) recently found that symbolic threat perceived by the Indonesian Muslim students amplified the impact of Islamic identification on the belief in Western people's conspiracies to create terrorism in Indonesia. Guided by these lines of reasoning, through this study we expect that the combination of realistic threat and symbolic threat posed by Western countries leads some Indonesian Muslims to believe that the Western countries have conspired to provoke terrorism in Indonesia.

According to Social Identity Theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1986), the level of identity salience qualifies the effect of group threat on intergroup attitudes and perceptions (Ellemers, Spears, & Doosje, 1999). Salient social identity than non-salient social identity makes people to become more curious and sensitive in responding to threat attributed to their group and motivates these people to act in ways to defend or promote their group (Branscombe, Ellemers, Spears, & Doosje, 1999). Identity salience refers to the definition of the self on the grounds of group membership shared with other people (Haslam, Oakes, Reynolds, & Turner, 1999). To the extent that individuals have internalized group membership they belong as an important part of the self, identity salience leads them to think, feel, and act in terms of their membership in that group (Wohl & Branscombe, 2008). Moreover, the more salient identity is the more likely it is that this identity will be enacted in a given situation. This probability of enacting a particular identity asserts identity salience and in turn this salience increases commitment to that identity (Vryan, Adler & Adler, 2003).

Religion in general is of fundamental importance for people's lives and religious groups in particular represent a significant, salient identity (Jones & McEwen, 2000; Peek, 2005; Verkuyten, 2007). The reason is that religion signifies a social identity that provides believers with a more distinctive, sacred worldview and enduring group membership than other social group identities (Ysseldyk, Matheson & Anisman, 2010). Islam in this regard can be a very typical case given that this religion provides strict guidelines technically termed the Five Pillars of Islam, the guidelines of which tend to make Islam a salient identity for its believers (Verkuyten, 2007). Thus, the salience of people's identity as a Muslim may play a key role in strengthening the consequence of intergroup threat on negative attitude in terms of Muslims' belief that Western countries, which are perceived as a source of the threat, are accountable for instigating terrorism in Indonesia.

Some studies have found that different kinds of intergroup threat elicit a number of negative emotions such as fear, disgust, guilt, and anger (Cottrell & Neuberg, 2005; Riek et al., 2006). In this study, we focus on the effect of intergroup threat on another negative emotion termed collective angst, denoting people's emotional responses based on concern over the vitality of these people's group future existence which is perceived in jeopardy (Wohl & Branscombe, 2008, 2009; Wohl, Giguère, Branscombe, & McVicar 2011; Wohl, Branscombe & Reysen, 2010). Recent research has confirmed that either a realistic threat in terms of group extinction (Halperin, Porat, & Wohl, 2013) or a symbolic threat in terms of group cultural discontinuity (Jetten & Wohl, 2012) trigger collective angst. Based on these findings, we thus argue that the more Muslims perceive the Western countries as realistically and symbolically threatening Islam the more they experience a feeling of collective angst toward the prospect of Islam.

Supports for intergroup attitudes, policy, and actions that detrimentally affect other groups in part are attributable to people's feeling of a collective angst originating from the perception that those groups are threatening these people's own group (Wohl, Squires, & Caouette, 2012). Belief in conspiracy theories may also have a detrimental effect since it has the negative potential to instigate a collective action and riots, especially after the events that endanger the social order such as terrorist attacks, wars, and economic crises (van Prooijen, 2012). This detrimental effect of belief in conspiracy theories, as discussed in the previous session, is attributable to the observation that the belief is inspirited by negative stereotyping and characterizations toward the suspected out-group (Kofta & Sedek, 2005). In the context of religious fundamentalism and extremism, belief in conspiracy theories is even characterized with demonization of the other groups believed to be the actors of the conspiracy (Donskis, 1998). Intergroup threat stemming from perception that power and values of another group are threatening those of the in-group may implicatively invoke in members of the in-group a feeling of collective angst and in turn, this feeling animates the belief that the first group has conspired to harm the latter group. Furthermore, within literature on Social Identity Theory of Group-Based Emotion (Mackie, Devos, & Smith, 2000), the empirical findings have demonstrated that social identity salience enhances the link between people's emotions toward an out-group and their tendency to think and act against this out-group. What we can infer from this rationale is that collective angst felt by Muslims may trigger this religious group's belief in the West's conspiracy theories to harm Islam. This effect of collective angst on belief in conspiracy theories is even more pronounced in conditions that enhance the salience of Muslims' Islamic identity. Furthermore, McCoy and Major (2003) argued that an out-group perceived as threatening an in-group elicits members of the latter group's negative emotions against those of the former group. These emotions ultimately contribute to increasing the in-group's negative attitudes and behaviors against the out-group. Deriving from these rationales, we, therefore, argue that intergroup threat triggers Muslims' collective angst, which then promotes this religious group's belief in the West's conspiracy theories. This role of collective angst in mediating the effect of intergroup threat on belief in conspiracy theories, drawing on Identity Theory of Group-Based Emotion (Mackie et al., 2000), is stronger when Muslims' Islamic identity is salient.

2. HYPOTHESES OF THE STUDY

Based on theoretical rationales and empirical findings discussed above, we generated several hypotheses as the following:

2.1 Hypothesis 1: Muslim participants in the high intergroup threat condition would demonstrate significantly higher degree of belief in conspiracy theories than those in the low intergroup threat condition.

2.2 Hypothesis 2: Muslim participants in the high intergroup threat condition would report significantly higher degree of belief in conspiracy theories than those in the low intergroup threat condition, but this effect would hold only in the condition in which participants' identity as a Muslim was made salient.

2.3 Hypothesis 3: Collective angst would mediate the effect of intergroup threat on belief in conspiracy theories.

2.4 Hypothesis 4: The more Muslim participants experienced a feeling of collective angst the more they would believe in the Western countries' conspiracy to create terrorism in Indonesia, but this association would be more pronounced in the condition in which participants' Muslim identity was made salient.

2.5 Hypothesis 5: Collective angst would mediate the effect of intergroup threat on belief in conspiracy theories, but only when the participants' social identity as a Muslim was made salient.

3. METHOD

3.1 Participants and design

Participants were 139 Muslim students from the department of Islamic Education, STAIN Pekalongan, Indonesia (89 women, 42 men, 8 participants did not mention their gender; Mage = 19.85, SDage = 1.32) who took part in this study voluntarily, in exchange of no rewards. The design of this study was a 2 (Intergroup Threat: high versus low) by 2 (Social Identity Salience: salient versus non-salient) between-subjects. We randomly assigned participants to one of the four combined conditions: high Intergroup Threat and salient Social Identity (n = 31), high Intergroup Threat and non-salient Social Identity (n = 36), low Intergroup Threat and salient Social Identity (n = 32), low Intergroup Threat and non-salient Social Identity (n = 40).

3.2 Procedure and measures

We administered this study in a classroom in which questionnaire containing all measures and manipulations was handed to participants. Measures were created on the basis of a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree - 5 = Strongly Agree) and by averaging the items. The materials in this study have been previously confirmed as in accordance to ethical codes and standards stipulated by the Research Board of Islamic State University of Pekalongan (STAIN Pekalongan). On the front page of the questionnaire, we provided participants with informed consent in which participants were asked to indicate their agreement to participate in the study by affixing their signature. On the first part of the questionnaire, participants were asked to read and comprehend an article about the extent to which Western countries tend to and are predicted to politically and culturally threaten Islamic worlds. Fictitiously published in a top-ranked Indonesian newspaper, this article was to manipulate Intergroup Threat. In the high Intergroup Threat condition, the article described that the threat was on the rise over the last three decades, and was predicted to further increase in the future. On the contrary, in the low Intergroup Threat condition, the threat as described in the article had decreased over the last three decades and was predicted to further decrease in the future. Following the article was a passage to manipulate Social Identity Salience (see Verkuyten & Hagendoorn, 1998; Haslam et al., 1999). In the salient Social Identity condition, the passage was a verbal instruction in which participants were asked to write a brief essay describing the nature and importance of their identity as a Muslim, along with their past, present, and future activities that are related to their status as a Muslim. In the non-salient Social Identity condition, the essay described participants' activities on a given day (a standard, neutral control prime).

After those two manipulations, participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they agreed with five statements to measure Collective Angst, which was developed by the authors (e.g., "I am anxious that having advanced knowledge and technology, Western countries undoubtedly can take over and change the Identity of Islam"; "I believe that Western countries can debilitate the existence of Islamic Worlds"; "I feel that Western countries are a threat to the sustainability of the uniqueness and purity of Islamic Worlds"; α = .84; corrected item-total correlations ranged from .51 to .74). Then, participants were also asked to answer two questions to assess the effectiveness of Intergroup Threat manipulation (i.e., "The trend of Western countries in threatening the Identity of Islamic Worlds has continued to increase, from 1980 to 2020"; "It was predicted that in the future, the Western countries will threaten the Identity of Islamic Worlds"; α = .82). Subsequently, participants were asked to answer two items to measure the credibility of the article to manipulate Intergroup Threat (. e., "The article about relationship between Western countries and Islamic Worlds written above can be trusted because it was based on a scientific research; "The article about relationship between Western countries and Islamic Worlds written above was indeed realistic"; α = .77).

On the final part of the questionnaire, participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they believed in four statements to measure Belief in Conspiracy Theories, which was developed by the authors (e.g., "Terrorism in Indonesia thus far has been catalysed by the Western countries' conspiracy to enervate the existence of Islamic Worlds"; "Terrorism in Indonesia was ignited by the creation of the Western countries' intelligence"; α = .83; corrected item-total correlations ranged from .55 to .79). Finally, participants were asked to fill out their demographic information, including age and gender. Upon finishing, participants were thanked and debriefed.

4. RESULTS

4.1 Manipulation Checks

An analysis of General Linear Model (GLM), with Intergroup Threat (coded 1 for high, coded 0 for low) and Social Identity Salience (coded 1 for salient, coded 0 for non-salient) entered as fixed factors, revealed a significant main effect of Intergroup Threat on the participants' agreement with statements that West countries tend to threaten Islamic Identity, B = -1.61, t = -6.13, p < .001, n_pˆ2= .22. Participants' agreement in the high Intergroup Threat condition (M = 3.85, SD = .88) was significantly higher than in the low Intergroup Threat condition (M = 2.16, SD = 1.16), F(1, 136) = 91.98, p < .001, n_pˆ2= .40. Neither main effect of Social Identity Salience nor interaction effect of Intergroup Threat x Social Identity Salience were significant-for the main effect of Identity Salience, B = -.04, t = -.15, p = .88; for the interaction effect of Intergroup Threat x Identity Salience, B = -.18, t = -.51, p = .61. This result indicated that the passage or article to manipulate Intergroup Threat was effective. Finally, participants' belief in statements that the first article to manipulate Intergroup Threat (M = 3.65, SD = .82) was scientific and realistic was significantly higher than the midpoint of 3, t(139) = 9.39, p < .001. This result means that the credibility of the article was satisfying.

4.2 Preliminary Analyses

Demographic variables of Gender (coded 1 for male and 0 for female) had no significant effect on Belief in Conspiracy Theories. Both male (M = 3.57, SD = .81) and female (M = 3.54, SD= .81) participants reported the same degree of Belief in Conspiracy Theories, t(129) = .17, p = .86. Age also turned out to have no significant effect on the Belief, B = .07, t = 1.30, p = .20. These results implied that Gender and Age did not need to be controlled in the hypothesis-testing analyses.

4.3 Primary Analyses

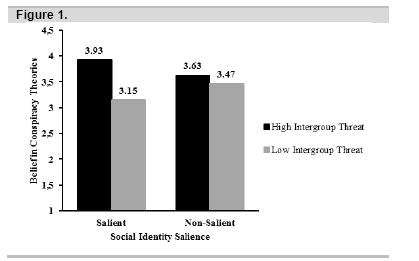

A GLM analysis, wherein Intergroup Threat and Social Identity Salience were entered as fixed factors, also revealed expected main effect of Intergroup Threat on Belief in Conspiracy Theories, B = -.78, t = -3.96, p < .001, np2 = .10. In line with Hypothesis 1, participants' Belief in Conspiracy Theories was significantly higher in the high Intergroup Threat condition (M = 3.78, SD = 3.77) than in the low Intergroup Threat condition (M = 3.31, SD = .79), F(1, 135) = 12.35, p = .001, np2 = .09. However, this main effect of Intergroup Threat on the Belief in Conspiracy Theories was qualified by the interaction between Intergroup Threat and Social Identity Salience, B = .62, t = 2.34, p = .02, np2 = .04. As shown in Figure 1, a simple slope analysis revealed that high Intergroup Threat (M = 3.93, SD = .70) triggered significantly higher degree of Belief in Conspiracy Theories than low Intergroup Threat (M = 3.15, SD = .90), F(1, 61) = 14.61, p < .001, but this effect emerged only in the salient Social Identity condition. On the contrary, in the non-salient Social Identity condition, the degree of Belief in Conspiracy Theories in the high Intergroup Threat condition (M = 3.63, SD = .84) and in the low Intergroup Threat condition (M= 3.47, SD = .67) was statistically the same, F(1, 74) = .81, p = .37. This result therefore corroborated Hypothesis 2.

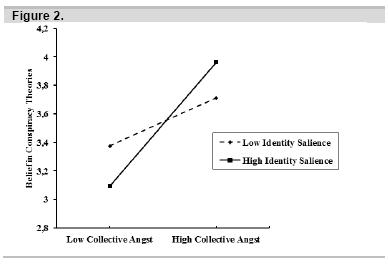

To test the role of Collective Angst in mediating the effect of Intergroup Threat on Belief in Conspiracy Theories, we used Preacher and Hayes' (2008) simple mediation procedure (SOBEL), by resampling the data 5000 times. Result showed that this mediating role of Collective Angst was indeed significant (booth indirect effect = .256, SE = .085, 95% LLCI= =.090, 95% ULCI = .422, z = 3.02, p = .003), in support of Hypothesis 3.To examine the role of Social Identity Salience in moderating the effect of Collective Angst on Belief in Conspiracy Theories, we used Hayes and Matthes' (2009) probing interaction procedure (MODPROB). The results (see Figure 2) revealed that among participants in the Salient Identity condition, Collective Angst was significantly related to Belief in Conspiracy Theories, b = .44, se = .09, t = 4.77, p < .001, 95% LLCI = .26, 95% ULCI = .62. However, among participants in the Non-Salient Identity condition, Collective Angst was unrelated to Belief in Conspiracy Theories, b = .17, se = .09, t = 1.85, p = .07, 95% LLCI = -.02, 95% ULCI = .35.

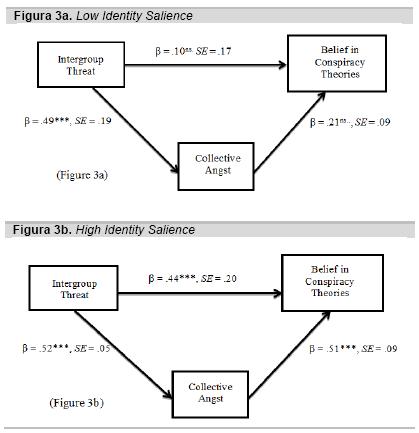

Finally, to test Hypothesis 5, we conducted a moderated mediation analysis using a bootstrap procedure (Preacher and Hayes, 2008, Model 15), by resampling the data 5000 times. In line with the prediction, Collective Angst in the Salient Identity condition proved to significantly mediate the effect of Intergroup Threat on Belief in Conspiracy Theories (Salient Identity condition = 1, booth indirect effect = .33, SE = .12, 95% LLCI = .10, 95% ULCI = .59; see Figure 3b), but such mediation effect was not significant in the Non-Salient Identity condition (Non-salient Identity condition = 0, booth indirect effect = .17, SE = .14, 95% LLCI = -.10, 95% ULCI = .44; see Figure 3a).

5. DISCUSSION

Belief in conspiracy theories reflects paranoid thinking (Pipe, 1997; Robins & Post, 1997). In intergroup relations, paranoid thinking contributes to external group attribution error, which makes people blaming an out-group instead of their group to be responsible for problems they encounter (Kramer, 1994). This rationale is in line with findings in some studies reporting that under threatening condition, people mistakenly evaluate the threatening out-group (Corneille, Yzerbyt, Rogier, & Buidin, 2001). This is also the case with blaming the Western countries, perceived as threatening the existence of Islam and Muslims, as perpetrators of terrorism in Indonesia. This belief in the West's conspiracy theories is starkly contradictory to the fact that the Indonesian authorities have convinced the public, supported with very transparent media coverage such as television, newspaper, internet, and radio, that it is indeed domestic Islamist radical groups that should be responsible for the terrorism (Sentana & Hariyanto, 2013).

The role of social identity salience in structuring the effect of intergroup threat on belief in conspiracy theories as found in this study asserts the truism of Group Identity Moderator Model (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). As explained by Verkuyten (2009), this model posits that social identity and intergroup threats interact to predict attitudes toward out-groups. This model has an alternative, which is called Group Identity Reactions (Jetten, Branscombe, Schmitt, & Spears, 2001) contending that perceived out-group threats are an antecedent of social identity, and strong social identity in turn leads to negative out-group attitudes. A limitation of this study is that social identity is not also measured using a social identification scale, but only manipulated using an informational scenario or a vignette. Next studies thereby can measure social identification with Muslims after intergroup threat to verify the verity of such alternative model.

Situational factors can be one of the determinants in activating the salience of Islam as a social identity. As reported by some studies, those factors that have ever made Muslim attain considerable prominence and salience as a social category are, among other things, the Rushdie Affair in 1988-89, the first Gulf war in 1991, and the September 11th, controversial Danish caricature of Prophet Muhammad (Ahmad & Evergeti, 2010; Hussain, 2007; Modood & Ahmad, 2007; Peek, 2005). All of these events in essence are not in favor of Muslims and thus threaten their existence, from which Muslims' negative attitudes and stereotyping against Western countries eventually emerge (Murshed, 2010). In Indonesian context, the discourse that incidents such as the September 11th and the insulting Danish caricature of Prophet Muhammad signify Zionist conspiracies to harm Islam has gained its popularity among a growing segment of Indonesian Muslim population (Daniels, 2007). These situational factors may implicitly have a role in providing a plausible answer for why salient identity as a Muslim as found in this study led intergroup threat and collective angst to amplify belief in conspiracy theories. However, to make this alternative explanation to become more explicit, next studies thus can directly create a vignette or a message framing with which participants are reminded with such situational factors. The message framing is then combined with salient Muslim identity to examine how this combination has a crucial role in augmenting the effect of intergroup threat and collective angst on belief in conspiracy theories.

The finding in this study that intergroup threat significantly triggered collective angst and the belief in conspiracy theories is in line with Hofstadter's (1966) argumentation. This scholar argued that the belief in conspiracy theories serves to regain people's sense of order and predictability in coping with threatening social events. In this regard, belief in conspiracy theories can be very instrumental to regulate people's distress in response to threatening social events, wherein people attribute the events to specific enemies rather than unmanageable factors or irregularities (Rothschild, Landau, Sullivan, & Keefer, 2012; Sullivan, Landau, & Rothschild, 2010). The Model of Compensatory Control (Kay, Whitson, Gaucher, & Galinsky, 2009) also describes that belief in conspiracy theories can be functional to reinstall people's sense of control over threatening events that evoke anxiety and discomfort. This mechanism of compensatory control implies that in dealing with threatening events, people can preserve their sense of order and controllability by believing that such events are attributable to conspiracies and even superstitions.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to link collective angst to belief in conspiracy theories. Existing studies within collective angst literature tend to focus on how this emotion predicts various in-group favoring attitudes and behaviors. These attitudes and behaviors include the desire to strengthen the in-group (Wohl et al., 2010), support for actions to protect in-group (Wohl et al., 2011), and forgiveness for in-group's past transgressions (Wohl & Branscombe, 2009). However, some recent research has shifted the focus to attitudes towards the out-group. In this new research direction, collective angst has been found to elicit unfavorable attitudes towards an out-group such as opposition to immigration (Jetten & Wohl, 2012) or decreased willingness to compromise with party in dispute (Halperin et al., 2013). The finding in this study that collective angst increases belief in the West's conspiracy theories thus complements the new research direction in which collective angst turns out to be accountable for evoking negative out-group attitudes.

Another limitation that deserves discussing is that this study involved only Javanese Muslim students as participants representing the majority ethnic group in Indonesia. As asserted by Jones (2002), among minority ethnic groups in Indonesian who are living in conflict areas, Indonesian national military (Tentara Nasional Indonesia: TNI) is believed as the true actor who provokes terrorism in Indonesia in an attempt to regain its role in government, which has been attenuated since the fall of Soeharto's military regime in 1998. Thus, next studies need to address this point by recruiting respondents from multifarious minority ethnic groups in Indonesia.

For the practical implications in this study, Indonesian government firstly requires being more concerned with implementing a counter strategy to reduce belief in conspiracy theories in the context of terrorism in Indonesia. In doing so, Indonesian government should conduct a comprehensive strategy by cooperating with other stakeholders. The reason is that a partial counter strategy, even conducted by experts, is no avail of attenuating belief in conspiracy theories since this belief is not easily falsifiable and implacable in nature y theories is also evidenced in the context of terrorism in Indonesia, in spite of successful Indonesian police in detaining and killing terrorists and a number of studies that proves that terrorist groups in Indonesia do exist (Singh, 2007). Secondly, the stakeholders with whom Indonesian government cooperates should be reliable ones. Belief in conspiracy theories is inspirited by a lack of trust (Goertzel, 1994); therefore, reduction of this belief should be done by reliable sources. The candidate will be Ulema as the assembly of scholars who have authorities on Islamic law in Indonesia. The program of the belief reduction can be a campaign of counterevidence (e.g., Newheiser, Farias, & Tausch, 2011) to illuminate Indonesian Muslims regarding the real existence of domestic radical Islamist groups accountable for perpetrating terrorism in Indonesia. Although this recommendation seemingly sounds more political rather than scientific, but we argue that sciences, more particularly social sciences, sometimes should pay attention to typical socio-cultural characteristics within a society to make their applications reasonable. In this manner, Indonesia is one of the countries with high index of power distance, a cultural dimension that has to do with the extent to which society members agree that the power is distributed unequally (Hofstede, 2007). People in high power distance countries rely on the authorities to deal with societal problems (Farh, Hackett, & Liang, 2007). Drawing on these rationales, we suggest that the reduction of belief in the West's conspiracy theories through the program of counterevidence conducted by Ulema as authoritative figures can be effective in Indonesian context.

6. REFERENCES

Ahmad, W. I. U., & Evergeti, V. (2010). The making and representation of Muslim identity in Britain: Conversations with British Muslim elites. Ethnic and Racial Studies 33(10), 1697-1717. [ Links ]

Arnaz, F., & Marhaenjati, B. (2013, August 22). Police seek to link newly arrested terror suspects to shooting of officers. The Jakarta Globe. Retrieved from http://www.thejakartaglobe.com/news/police-seek-to-link-newly-arrested-terror-suspects-to-shooting-of-officers/. [ Links ]

Azra, A. (2000). The Islamic factor in post-Soeharto Indonesia. In C. Manning & P. van Diermen (Eds.), Indonesia in transition: Social aspect of reformasi and crisis (pp. 309-319). Canberra & Singapore: Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University & Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. [ Links ]

Azra, A. (2006). Indonesia, Islam, and democracy: Dynamics in a global context. Jakarta: Equinox Publishing. [ Links ]

Branscombe, N., Ellemers, N., Spears, R., & Doosje, B. (1999). The context and content of social identity threat. In N. Ellemers, R. Spears & B. Doosje (Eds.), Social identity: Context, commitment, content (pp. 35-58). Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Branscombe, N. R., & Wann, D. L. (1992). Physiological arousal and reactions to out-group members during competitions that implicate an important social identity. Aggressive Behavior, 18(2), 85-93. [ Links ]

Castells, M. (2011). The power of identity: The information age: Economy, society, and culture. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Corneille, O., Yzerbyt, V. Y., Rogier, A., & Buidin, G. (2001). Threat and the group attribution error: When threat elicits judgments of extremity and homogeneity. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(4), 437-446. [ Links ]

Cottrell, C. A., & Neuberg, S. L. (2005). Different emotional reactions to different groups: A sociofunctional threat-based approach to prejudice. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 88(5), 770-789. [ Links ]

Daniels, T. P. (2007). Liberals, moderates and jihadists: Protesting Danish cartoons in Indonesia. Contemporary Islam, 1(3), 231-246. [ Links ]

Donskis, L. (1998). The conspiracy theory, demonization of the other. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 11(3), 349-360. [ Links ]

Ellemers, N., Spears, R., & Doosje, B. (Eds.) (1999). Social identity: Context, commitment, content. Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Esposito, J. L. (2000). Political Islam and the West. Joint Force Quarterly, Spring, 24-49. [ Links ]

Fair, C.C, & Shepherd, B. (2006). Who supports terrorism? Evidence from fourteen Muslim countries. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 29(1), 51 -74. [ Links ]

Farh, J. L., Hackett, R. D., & Liang, J. (2007). Individual-level cultural values as moderators of perceived organizational support-employee outcome relationships in China: Comparing the effects of power distance and traditionality. Academy of Management Journal, 50(3), 715-729. [ Links ]

Goertzel, T. (1994). Belief in conspiracy theories. Political Psychology, 15, 731 -742. [ Links ]

Halperin, E., Porat, R., & Wohl, M. J. (2013). Extinction threat and reciprocal threat reduction: Collective angst predicts willingness to compromise in intractable intergroup conflicts. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 16(6), 797-813. [ Links ]

Haslam, S. A., Oakes, P. J., Reynolds, K. J., & Turner, J. C. (1999). Social identity salience and the emergence of stereotype consensus. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(7), 809-818. [ Links ]

Hayes, A. F., & Matthes, J. (2009). Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behavior Research Methods, 41(3), 924-936. [ Links ]

Hofstadter, R. (1966). The paranoid style in American politics. In R. Hofstadter (Ed.), The paranoid style in American politics and other essays (pp. 3-40). New York, NY: Knopf. [ Links ]

Hofstede, G. (2007). Asian management in the 21st century. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 24(4), 411-420. [ Links ]

Hussain, A. J. (2007). The media's role in a clash of misconceptions: The case of the Danish Muhammad cartoons. The Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 12(4), 112-130. Issues, 69, 54-73. [ Links ]

Imhoff, R., & Bruder, M. (2014). Speaking (un- ) truth to power: Conspiracy mentality as a generalised political attitude. European Journal of Personality, 28(1), 25-43. [ Links ]

Jetten, J., Branscombe, N.R., Schmitt, M.T., & Spears, R. (2001). Rebels with a cause: Group identification as a response to perceived discrimination from the mainstream. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 1204-1213. [ Links ]

Jetten, J., & Wohl, M. J. (2012). The past as a determinant of the present: Historical continuity, collective angst, and opposition to immigration. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42(4), 442-450. [ Links ]

Jones, S. (2002, October 27). Who are the terrorists in Indonesia? Conspiracy theories over the Bali bombing are rife in Indonesia. The Observer. Retrieved from http://www.crisisgroup.org/en/regions/asia/south-east-asia/indonesia/op-eds/jones-who-are-the-terrorists-in-indonesia-conspiracy-theory-over-the-bali-bombing-are-rife-in-indonesia.aspx. [ Links ]

Jones, S. R., & McEwen, M. K. (2000). A conceptual model of multiple dimensions of identity. Journal of College Student Development, 41(4), 405-414. [ Links ]

Kay, A. C., Whitson, J. A., Gaucher, D., & Galinsky, A. D. (2009). Compensatory control achieving order through the mind, our institutions, and the heavens. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(5), 264-268. [ Links ]

Khisbiyah, Y. (2009). Contested discourses on violence, social justice, and peacebuilding among Indonesian Muslims. In C. J. Montiel & N. M. Noor (Eds.), Peace psychology in Asia (pp. 123-145). New York: Springer. [ Links ]

Kofta, M. (1995). Stereotype of a group as-a-whole: The role of diabolic causation schema. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 26(2), 83-96. [ Links ]

Kofta, M., & Sedek, G. (2005). Conspiracy stereotypes of Jews during systemic transformation in Poland. International Journal of Sociology, 35(1), 40-64. [ Links ]

Kofta, M., Sedek, G., & Slawuta, P. N. (2011.). Beliefs in Jewish conspiracy: The role of situation threats to ingroup' power and positive image. Paper presented at the 34th International Society of Political Psychology (ISSP) conference, Istanbul, Turkey. [ Links ]

Kramer, R. M. (1994). The sinister attribution error: Paranoid cognition and collective distrust in organizations. Motivation and Emotion, 18(2), 199-230. [ Links ]

Mashuri, A., & Zaduqisti, E. (2014). The role of social identification, intergroup threat, and out-group derogation in explaining belief in conspiracy theory about terrorism in Indonesia. International Journal of Research Studies in Psychology, 3, 35-50. [ Links ]

Mackie, D. M., Devos, T., & Smith, E. R. (2000). Intergroup emotions: Explaining offensive action tendencies in an intergroup context. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(4), 602-616. [ Links ]

McCoy, S. K., & Major, B. (2003). Group identification moderates emotional responses to perceived prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(8), 1005-1017. [ Links ]

Modood, T., & Ahmad, F. (2007). British Muslim perspectives on multiculturalism. Theory, Culture and Society, 24, 2, 187-213. [ Links ]

Moghaddam, F. M. (2008). How globalization spurs terrorism: The lopsided benefits of one world and why that fuels violence. Westport: Praeger Security International. [ Links ]

Moten, A. R. (2005). Modernisation and the process of globalisation. In K. Nathan & M. H. Kamali (Eds.), Islam in Southeast Asia: Political, social, and strategic challenges for the 21st century (pp. 231-252). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. [ Links ]

Mullen, B., Brown, R., & Smith, C. (1992). Ingroup bias as a function of salience, relevance, and status: Anintegration. European Journal of Social Psychology, 22(2), 103-122. [ Links ]

Newheiser, A.-K., Farias, M., & Tausch, N. (2011). The functional nature of conspiracy beliefs: Examining the underpinnings of belief in the Da Vinci Code conspiracy. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(8), 1007-1011. [ Links ]

Peek, L. (2005). Becoming Muslim: The development of a religious identity. Sociology of Religion, 66(3), 215-242. [ Links ]

Pipes, D. (1997). Conspiracy: How the paranoid style flourishes and where it comes from. New York: Simon & Schusters. [ Links ]

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879-891. [ Links ]

Putra, I. E., & Sukabdi, S. A. (2013). Basic concepts and reasons behind the emergence of religious terror activities in Indonesia. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 16(2), 83-91. [ Links ]

Riek, B. M., Mania, E. W., & Gaertner, S. L. (2006). Intergroup threat and out-group attitudes: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(4), 336-353. [ Links ]

Robins, R. S., & Post, J. M. (1997). Political paranoia: The psychopolitics of hatred. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Robison, K. K., Crenshaw, E. M. & Jenkins, J. C. (2006). Ideologies of violence: The social origins of Islamist and leftist transnational terrorism. Social Forces, 84(4), 2009-2026. [ Links ]

Rothschild, Z. K., Landau, M. J., Sullivan, D., & Keefer, L. A. (2012). A dual-motive model of scapegoating: displacing blame to reduce guilt or increase control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(6), 1148-1163. [ Links ]

Sapountzis, A., & Condor, S. (2013). Conspiracy accounts as intergroup theories: Challenging dominant understandings of social power and political legitimacy. Political Psychology, 34(5), 731 -752. [ Links ]

Sentana, M., & Hariyanto, J. (2013, January 5). Indonesia police kill five alleged terrorists. The Jakarta Post. Retrieved from http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323374504578223290283017294.html. [ Links ]

Sharp, D. (18). Advances in conspiracy theory. The Lancet, 372(9647), 1371-1372. [ Links ]

Singh, B. (2007). The Talibanization of Southeast Asia: Losing the war on terror to islamist extremists. Greenwood Publishing Group. [ Links ]

Solahudin. (2013). The roots of Terrorism in Indonesia: From Darul Islam to Jem'ah Islamiyah. (D. McRae, Trans.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

Stephan, W. G., Diaz-Loving, R., & Duran, A. (2000). Integrated threat theory and intercultural attitudes Mexico and the United States. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 31(2), 240-249. [ Links ]

Stephan, W. G., & Stephan, C. W. (1996). Predicting prejudice. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 20, 409-425. [ Links ]

Stephan, W. G., & Stephan, C. W. (2000). An integrated threat theory of prejudice. In S. Oskamp (Ed.), Reducing prejudice and discrimination (pp. 2346). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Suciu, E. M. (2008). Signs of anti-semitism in Indonesia. Degree thesis, Department of Asian Studies, The University of Sydney, Sydney. [ Links ]

Sullivan, D., Landau, M. J., & Rothschild, Z. K. (2010). An existential function of enemyship: evidence that people attribute influence to personal and political enemies to compensate for threats to control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(3), 434-449. [ Links ]

Swami, V. (2012). Social psychological origins of conspiracy theories: The case of the Jewish conspiracy theory in Malaysia. Frontiers in Personality Science and Individual Differences, 3, 280. [ Links ]

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of inter-group behavior. In S. Worchel and L. W. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Chicago: Nelson-Hall. [ Links ]

van Prooijen, J. W. (2012). Suspicions of injustice: The sense-making function of belief in conspiracy theories. In E. Kals & J. Maes (Eds.), Justice and conflict: Theoretical and empirical contributions (pp. 121 -132). Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. [ Links ]

van Prooijen, J. W., & Jostmann, N. B. (2013). Belief in conspiracy theories: The influence of uncertainty and perceived morality. European Journal of Social Psychology, 43(1), 109-115. [ Links ]

Verkuyten, M. (2007). Religious group identification and inter-religious relations: A study among Turkish-Dutch Muslims. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 10(3), 341 -357. [ Links ]

Verkuyten, M. (2009). Support for multiculturalism and minority rights: The role of national identification and out-group threat. Social Justice Research, 22(1), 31 -52. [ Links ]

Verkuyten , M., & Hagendoorn, L. (1998). Prejudice and self-categorization: the variable role of authoritarianism and in-group stereotypes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24(1), 99-110. [ Links ]

Vryan, K.D., Adler, A., & Adler, P. (2003). Identity. In L.T. Reynolds & N.J. Herman-Kinney (Eds.), Handbook of symbolic interactionism (367-390). Oxford: AltaMira Press. [ Links ]

Webber, D. (2006). A Consolidated patrimonial democracy? Democratization in post-Suharto in Indonesia. Democratization, 13(3), 396-420. [ Links ]

Wohl, M. J. A., & Branscombe, N. R. (2008). Collective angst: How threats to the future vitality of the ingroup shape intergroup emotion. In H. Wayment and J. Bauer (Eds.), Transcending self-interest: Psychological explorations of the quiet ego (pp. 171-181). Washington: American Psychological Association. [ Links ]

Wohl, M. J. A., & Branscombe, N. R. (2009). Group threat, collective angst and ingroup forgiveness for the war in Iraq. Political Psychology, 30(2), 193-217. [ Links ]

Wohl, M.J.A., Branscombe, N.R., & Reysen, S. (2010). Perceiving your group's future to be in jeopardy: Extinction threat induces collective angst and the desire to strengthen the ingroup. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(7), 898-910. [ Links ]

Wohl, M. J. A., Giguère, B., Branscombe, N. R., & McVicar, D. N. (2011). One day we might be no more: Collective angst and protective action from potential distinctiveness loss. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41(3), 289-300. [ Links ]

Wohl, M. J., Squires, E. C., & Caouette, J. (2012). We were, we are, will we be? The social psychology of collective angst. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6(5), 379-391. [ Links ]

Ysseldyk, R., Matheson, K., & Anisman, H. (2010). Religiosity as identity: Toward an understanding of religion from a social identity perspective. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14(60), 60-71. [ Links ]